Abstract

Nipah virus is a zoonotic paramyxovirus that causes severe respiratory and/or encephalitic disease in humans, often resulting in death. It is transmitted from pteropus fruit bats, which serve as the natural reservoir of the virus, and outbreaks occur on an almost annual basis in Bangladesh or India. Outbreaks are small and sporadic, and several cases of human-to-human transmission have been documented as an important feature of the epidemiology of Nipah virus disease. There are no approved countermeasures to combat infection and medical intervention is supportive. We recently generated a recombinant replication-competent vesicular stomatitis virus-based vaccine that encodes a Nipah virus glycoprotein as an antigen and is highly efficacious in the hamster model of Nipah virus disease. Herein, we show that this vaccine protects African green monkeys, a well-characterized model of Nipah virus disease, from disease one month after a single intramuscular administration of the vaccine. Vaccination resulted in a rapid and strong virus-specific immune response which inhibited virus shedding and replication. This vaccine platform provides a rapid means to afford protection from Nipah virus in an outbreak situation.

Keywords: Nipah virus, vaccine, vesicular stomatitis virus, immune response, paramyxovirus

Introduction

Nipah virus is a member of the family Paramyxoviridae, genus Henipavirus. Nipah virus causes severe disease in humans characterized by a respiratory and/or encephalitic syndrome. Following the initial Malaysian outbreak, which caused 107 fatalities from 276 cases, outbreaks have occurred almost annually in Bangladesh or India, with case fatality rates averaging approximately 70% and as high as 100% in small isolated outbreaks [1–5]. Nipah virus is zoonotic and the natural reservoir has been identified as pteropus fruit bats (flying foxes) [6,7]. A major route of transmission to humans is thought to be ingestion of date palm sap contaminated by Nipah virus-infected bats [8]. Outbreaks also involve human-to-human transmission events [9–13]. Disease can be rapid with short incubation times, or can be relapsing in nature, with encephalitis leading to death several years after exposure [14,15].

Currently, there are no approved vaccines or therapeutics to combat Nipah virus infection or disease, although several vaccines have been tested in animal models for their ability to elicit specific immune responses and/or protect animals from disease following challenge, reviewed in [16]. We recently generated a live-attenuated replication-competent recombinant vesicular stomatitis virus (VSV) that is devoid of the native glycoprotein (G), which is a major virulence factor and VSV immunogen, and that expresses the glycoprotein of Nipah virus (NiVG) [17]. Paramyxoviruses require both the fusion (F) and G for cellular entry, so to facilitate entry in place of the VSVG, as well as to specifically target immune-modulating cell types, we engineered our vector to encode and express the glycoprotein of Zaire ebolavirus (EBOV-GP) [18]. We previously tested the efficacy of this vector (rVSV-EBOV-GP-NiVG) in the hamster model of Nipah virus disease and it afforded complete protection from a high dose of Nipah virus when administered 28 days prior to challenge [17]. Protection was attributed to the G protein of Nipah virus, as the rVSV-EBOV-GP backbone did not protect hamsters from disease.

The “gold standard” for a vaccine’s efficacy for hemorrhagic fever-causing viruses, for which human trials are not feasible, is typically a non-human primate model that recapitulates human disease. The African green monkey (AGM) has recently been established and described as a model for Nipah virus, and disease in this model is strikingly similar to that of human disease [19]. Nipah virus is highly virulent in this model and causes severe respiratory disease and pathology and generalized vasculitis within the first two weeks after inoculation [19]. To satisfy the FDA’s two animal rule, we sought to test the efficacy of this vaccine vector in the AGM model. We found that this vaccine induces a robust and rapid immune response that is protective and prevents Nipah virus replication and disease when administered as a single dose four weeks prior to challenge.

Materials and Methods

Ethics Statement

The use of study animals was approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the Rocky Mountain Laboratories and experiments were performed following the guidelines of the Association for Assessment and Accreditation of the Laboratory Animal Care by certified staff in an approved facility.

Vaccination and challenge of AGMs

Six AGMs were used in this study and divided into two groups of three animals. Mock vaccinated animals (AGM4-6, two male and one female, 3.5–4.7 kg) were administered sterile medium by intramuscular (i.m.) injection into the right hind limb. Vaccinated animals (AGM1-3, two female and one male, 3.3–4.1 kg) received 1 × 107 PFU of the rVSV-EBOV-GP-NiVG vaccine described previously [17]. Exams, consisting of physical examinations, blood draws, oral and nasal swabbing were performed at the time of vaccination (−29d) and on days −15, 0, 3, 5, 7, 10, 14 and terminal (16 or 17) relative to challenge. AGMs were observed daily and scored for clinical signs of disease, which included parameters related to overall appearance (up to 15 points), skin and fur (up to 10 points), respirations (up to 15 points), feces and urine up to 10 points), food intake (up to 10 points) and locomotion (up to 35 points). Animals were considered terminally ill and euthanized with a sore or 35 or more. For challenge, all animals received a total of 105 TCID50 of Nipah virus, Malaysian strain, via the intratracheal route as previously established [19]. AGM6 was euthanized 10 days post-challenge due to severe clinical disease. The remaining animals were euthanized on days 16 or 17 post-challenge. At the time of euthanasia, tissues were collected for evaluation of viral load.

Nipah Virus Quantitation

To determine the viral load in the blood, swab samples and tissues, we isolated total RNA from these samples and performed a one-step probe-based quantitative RT-PCR specific for the N gene to quantitate viral RNA abundance in the samples as described previously [20]. We attempted virus isolation from swab and whole blood samples from days 3, 5, 7, 10 and 14, and from brain (frontal, cerebellum and stem) and lung tissue (one sample from each of the 6 lobes) from all animals as described previously [20].

Serology

Serum was collected at the time of examinations and accessed for the presence of Nipah virus-specific antibodies by ELISA and/or neutralizing activity as done previously [21].

Flow Cytometry

For the analysis of the immune status in the blood, we isolated PBMCs by incubating whole blood with 2% dextran T-500 (Sigma) in PBS for 0.5 h at 37 °C and removing the clear fraction. Cells were washed in PBS and residual red blood cells were lysed using ACK buffer (Gibco). After washing, 5 × 105 cells were stained with Live/Dead fixable yellow dye (Invitrogen), followed by antibodies to CD3 (SP34-2-PE-Cy7), CD4 (OKT4-eFluor450), CD8 (SK1-APC), CD28 (CD28.2-PE) and CD95 (DX2-FITC) at predetermined concentrations (all from BD Biosciences with the exception of CD4, which was from eBioscience). For stimulation experiments, cells were rested overnight and treated with PMA (25 ng/mL) and ionomycin (250 ng/mL) for 6 h, with the addition of brefeldin A (10 μg/mL) for the final 4.5 h prior to staining. For intracellular staining, cells were fixed in Fix/Perm (BD) after first surface staining with CD3, CD4 and CD8. After washing in Perm/Wash (BD), cells were stained with antibodies to IFNγ (B27-FITC) and granzyme B (GB11-AlexaFluor700) (BD Biosciences). Polychromatic flow cytometry was performed using a LSR II cytometer equipped with FACS Diva software (BD) and data was analyzed using FlowJo software (TreeStar).

Statistics

The flow cytometry data, represented as the percent of total cells expressing the indicated markers, were averaged within the vaccinated and control groups. Data are represented as the mean and standard deviations from these animals and significance was determined between these groups using a student’s t-test with significance set at p ≤ 0.05.

Results

Clinical Observations

We used six AGMs for this study, of which three received 107 plaque forming units of the rVSV-EBOV-GP-NiVG vaccine by i.m. injection (AGM1-3) and three were mock vaccinated (AGM4-6). The animals were monitored daily for clinical signs of disease following vaccination and none of the animals showed any adverse effects. Twenty-nine days after vaccination, all animals were challenged with 105 tissue culture infectious dose 50% (TCID50) of Nipah virus-Malaysia via intratracheal installation. Following challenge, several AGMs had a reduced appetite for the first three days, resulting in scores of around 5–7. Beginning on day five, AGM6 had increased respiration rates, which became progressively worse and this animal had to be euthanized 10 days after challenge due to our clinical scoring criteria. Beginning on day eight after challenge, AGM4 and AGM5 had shallow and increased respirations, which became progressively worse and these two animals became lethargic. However, these two animals did not meet the required score (35) for euthanasia and showed signs of recovery by 13–14 days post-challenge (Fig. 1). The three vaccinated animals never showed clinical signs of disease compatible with Nipah virus disease following challenge. Due to the observation that the two control animals were showing signs of recovery, we chose to necropsy all remaining animals (with the exception of AGM6, which was euthanized 10 days post-infection) on days 16 or 17 post-challenge to determine the extent of virus replication and dissemination and to compare virus abundance in tissues of the two remaining control animals to the 3 vaccinated animals.

Figure 1. Clinical observations.

AGMs were scored daily for signs of clinical disease following challenge with Nipah virus. Vaccinated animals (AGM1-3) had minimal decreases in appetite as a reaction to the anesthesia and procedures. AGM4 and AGM5 had increased respiratory rates, hunched posture and decreased appetite staring on day 8 and worsening, until resolving on days 14 and 15 respectively. AGM6 had increased respiratory rates and decreased food intake starting in day five post-challenge, which became progressively worsened until day 10, at which time this animal was euthanized as per approved humane endpoint scoring criteria.

Nipah Virus Shedding and Replication

We harvested tissues from the respiratory tract, brain and other major organs to determine the extent of virus replication in the control animals, and the possibility of protection in the vaccinated animals. We also swabbed the nasal and oral cavities during examinations at the indicated time points to assess viral shedding. All swabs taken from the vaccinated animals were negative for the duration of the experiment. All control animals shed virus via both oral and nasal routes, starting between days 3 and 5, and 3 and 10, respectively (Fig. 2A and B). Similarly, all control animals became viremic starting by day 5 or 7, whereas the vaccinated animals remained negative throughout the study (Fig. 2C). Examination of the tissues for viral RNA by qRT-PCR showed that virus consistently replicated to the highest titers in AGM6, which was necropsied on day 10 post-challenge (Fig. 2D). Animal AGM4 had virus RNA in all tissues examined with the exception of the nasal mucosa. AGM5 was positive for seven of the 11 tissues tested, although the levels of virus in these tissues were generally higher than that for AGM4 in the respective tissues. For the vaccinated animals, only a total of two samples from all 3 animals showed weak positivity for virus, near the level of detection for the assay.

Figure 2. Virus shedding, viremia and tissue loads.

AGMs were swabbed on examination days for the detection of viral RNA or to attempt virus isolation from oral (A) and nasal (B) membranes. Whole blood was also obtained at these times for the detection of virus (C). Similarly, tissue samples (D) were taken from each animal at the time of necropsy to analyze for the presence of Nipah virus. To quantitate viral RNA, we used a 1-step qRT-PCR specific for the nucleocapsid gene and normalized the cycle threshold (CT) values to that of a standard curve generated from a stock of Nipah virus of a known titer to extrapolate TCID50 equivalents contained in the samples. Asterisks (*) indicate that the bar represents the geometric mean from multiple samples (six lung lobes or left and right bronchi). Virus isolation was attempted on swab, blood and select tissue (lung and brain only) samples. Plus signs (+) indicate successful isolation of viable Nipah virus on Vero E6 cells for a particular sample.

We attempted virus isolation from all swab and blood samples taken from days three to 14 post-challenge, and from all lung samples (six lobes) and brain samples (frontal, cerebellum and brain stem). As previously reported, isolation from the blood was relatively efficient and we were able to isolate virus from all control animals in at least one sample (Fig. 2C) [19]. We were also able to isolate virus from several swab samples and at least one brain or lung sample from each control animal (Fig 2A, B, and D). We were unable to isolate Nipah virus from any sample from the vaccinated animals.

Immune Responses to Vaccination and Challenge

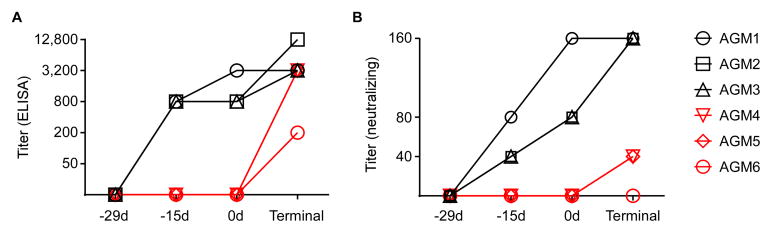

We performed experiments to examine both the antibody responses as well as cellular responses throughout the vaccination and/or challenge phases of this study. All animals were seronegative for Nipah virus in both ELISA and neutralization assays at the onset of the study (Fig. 3A and B). By 14 days post-vaccination (−15d), all three vaccinated animals had Nipah virus-specific antibodies with titers of 800, measured by ELISA using antigen prepared from purified Nipah virus particles. These titers were similar at the time of challenge, but increased at the time of the terminal bleed (16–17 days post-challenge). The three control animals only had measurable antibody titers at their terminal bleed, suggesting that a specific immune response was mounted to Nipah virus challenge (Fig. 3A). AGM6 had the lowest terminal titers, likely due to the fact that this animal was euthanized at an earlier time point compared to the other controls.

Figure 3. Antibody responses to vaccination and challenge.

Sera were collected from AGMs before vaccination and throughout the course of the experiment to examine antibody responses. An ELISA (A) was performed using detergent-lysed purified Nipah virus particles as an antigen along with serial 4-fold dilutions of the sera, starting at a 50-fold dilution to measure Nipah virus-specific antibodies. Vaccinated animals (black) has measureable titers within 14 days, whereas control animals (red) and antibodies to Nipah virus only after challenge. We also performed a neutralizing assay (B) using serial 2-fold dilutions of sera starting at a 20-fold dilution, and incubating this with 200 TCID50 of Nipah virus before adding to Vero E6 cells and scoring for CPE. Vaccination resulted in the production of neutralizing antibodies within 14 days (black) whereas control animals (red) only generated low levels of neutralizing antibodies after challenge (red).

Virus neutralization showed a similar trend (Fig 3B). Fourteen days after vaccination (−15d), the three control animals were unable to neutralize Nipah virus, whereas all three vaccinated animals had neutralizing titers of at least 40. These titers were higher at the time of challenge, but remained negative at this time in the mock-vaccinated animals. At the terminal bleed, all vaccinated animals had neutralizing titers of 160. AGM4 and AGM5 had titers of 40 at this time point, suggesting a specific response, although AGM6 remained negative for neutralization activity.

We examined the cellular response to vaccination/challenge by performing flow cytometry for lymphocyte markers and cytokines of peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) obtained during examinations and at the terminal bleed. Vaccinated animals had a statistically significant increase in the percentage of CD8+ lymphocytes (CD3+) 14 days after vaccination (−15d) (Fig. 4A and B). This population returned to levels similar to the control group at the time of challenge, but were again significantly increased compared to control animals following challenge. These cells were of an effector memory (EM) phenotype as CD3+/CD8+ cells had significantly increased percentages of cells with a CD28−/CD95+ phenotype, following a similar trend as the overall CD3+/CD8+ T cell population (Fig. 4C). To determine the effector status of these cells, we performed non-specific stimulations (PMA/ionomycin) followed by intracellular cytokine staining of PBMC samples starting at the challenge day and throughout the remainder of the experiment. The percentage of CD8+ T cells expressing interferon-γ (IFNγ) was significantly increased in the vaccinated animals over that of the control animals starting at seven days post-challenge (Fig. 4D). Similarly, the percentage of these cells containing granzyme B was significantly increased by three days post-challenge (Fig. 4E).

Figure 4. Cellular immune responses to vaccination and challenge.

Throughout the course of the experiment, PBMCs were isolated following examinations and stained with various immune cell markers for flow cytometry. A sample gating strategy is shown in panel A. Cells were surface stained for CD3 and CD8 antigens (B) or CD3, CD8, CD28 and CD95 (C) and their populations were determined as percentages of T cells (CD3+ cells) expressing these antigens. A sample of cells was also non-specifically stimulated with PMA and ionomycin for 6 hours and stained with CD3 and CD8, followed by permeabilization and intracellular staining for IFNγ (D) and granzyme B (E). Graphs represent the averages and standard deviations of the percentages of cells positive for the indicated antigens on the y-axis. Asterisks (*) indicate significant differences between vaccinated (black) and control (red) animals, with p ≤ 0.05 using a student’s t-test.

Discussion

Efficacy studies in non-human primate models are preferred in addition to small animal models for the approval of therapeutics and novel vaccines when human efficacy trials cannot be performed. Herein, we describe a viable single-dose vaccination platform that is efficacious in completely protecting AGMs from Nipah virus disease. Vaccinated animals had no disease signs related to challenge with Nipah virus and were completely protected. All mock vaccinated animals developed clinical signs of Nipah virus disease, shed virus from oral and nasal cavities, became viremic, and Nipah virus replicated throughout the respiratory tract and was isolated from various samples from each animal. Conversely, vaccinated animals remained healthy throughout the study and these animals had no measureable virus either in the blood or shed from the mucosal cavities tested. Although the AGM model has been characterized as a lethal model [19], we only had one of three animals progress to lethal disease, despite all animals becoming clinically sick. The two control animals that did not progress to terminal disease using our scoring criteria for euthanasia (AGM4 and AGM5) had clear clinical signs of Nipah virus disease and Nipah virus RNA measured in the swabs and blood were similar to, or even higher than the control animal (AGM6) that was euthanized due to severe disease. Nipah virus RNA levels were lower in the tissues of the two control animals that showed signs of recovery, likely because they were necropsied approximately one week after AGM6 was, and infection was likely resolving at that time. This is corroborated by the measurement of viral shedding and viremia, where on days 7 and 10, all three animals showed similar levels of viral RNA. It is possible that the control animals (AGM4 and AGM5) might have progressed to encephalitic disease if not euthanized. Nipah virus RNA was relatively abundant in the CNS, especially for AGM4, and we were able to isolate virus from the cerebellum of this animal and frontal brain of AGM5, indicating that Nipah virus was replicating in the brain at the time of euthanasia.

To date, two vaccine approaches have been tested in the AGM model of Nipah virus disease. A subunit vaccine composed of the G of Hendra virus, a related paramyxovirus of the same genus as Nipah virus, protected AGMs from Nipah virus challenge, and a measles virus-based vaccine expressing the Nipah virus G as an antigen [22,23]. For the subunit vaccine, a prime-boost schedule was used along with both Allhydrogel and CpG oligonucleotides as adjuvants, and this completely protected animals from a fatal dose of the virus. The measles virus vector approach also used a prime boost schedule and animals were challenged two weeks after the boost via the intraperitoneal route. Although the two control animals did not develop severe disease in this experiment, they had decreased body temperature and histopathologic changes in the lungs and brains upon euthanasia, whereas the two vaccinated animals maintained body temperature and showed no histopathologic changes in the tissues examined. Nipah virus replication (neither RNA, isolations, nor immunohistochemical analyses) was not examined in this experiment, so it is unknown whether the vaccine provided complete protection. In addition to these vaccine approaches, a human monoclonal antibody (m102.4) has been shown to protect AGMs from both Hendra as well as Nipah virus disease [24,25].

Our vaccine platform has several advantages that make it attractive as a vaccine candidate for Nipah virus. We have previously demonstrated that this vector can protect hamsters, a sensitive Nipah virus disease model, 28 days after a single administration and that protection is specific to the Nipah virus G antigen, as the backbone alone was not protective [17]. The efficacy of this general vectored platform (rVSV-EBOV-GP) has been demonstrated in several studies and affords protection against Ebola virus challenge in both rodents and non-human primates. The vector containing the GP from a filovirus and devoid of the native G of VSV protects non-human primates from homologous challenge with filoviruses [26,27] and this, and similar vectors encoding the GP of other filoviruses, have proved efficacious when administered post-exposure, making this an extremely attractive platform for vaccination against highly pathogenic VHFs that cause acute disease [28–31]. Additionally, these vectors have shown pre- and post-exposure (peri-exposure) efficacy when engineered to express the Andes hantavirus glycoprotein precursor in place of, or in addition to the ebolavirus GP [18,32]. One potential benefit of this platform is the possible specific cell targeting mediated by the incorporation of the ebolavirus GP, which has a tropism for dendritic cells and other innate immune cells. Stimulation of these cell types, leading to secretion of immune-modulation cytokines, might account for the effectiveness of this vaccine in post-exposure situations. This is evidenced by the observation that the vector alone (rVSV-EBOV-GP) is able to protect hamsters form challenge with an unrelated virus (Andes virus) when given around the time of, and even after, inoculation with Andes virus [18].

The mechanism in which this vaccine protects against Nipah virus infection is likely to involve its ability to elicit a neutralizing antibody response. Passive transfer of sera from rVSV-EBOV-GP-NiVG-vaccinated hamsters was able to protect naïve hamsters from disease [17]. In addition, a human monoclonal anti-Hendra virus antibody (m102.4) that has strong neutralizing properties can protect AGMs from henipaviruses when given post-exposure, demonstrating that antibodies alone can protect against Henipavirus disease [24]. Depletion studies in macaques have shown that antibodies are required for our particular vaccine platform’s efficacy against Zaire ebolavirus [33]. In this study, the vaccine elicited a neutralizing antibody response within 14 days after administration and this is likely important for the complete protection. In addition to B cell responses, we were able to measure cellular responses to vaccination. The proportions of both CD8+ T cells, as well as T cells of an effector phenotype (CD28−/CD95+), were increased within 14 days of vaccination, and again following virus challenge, suggesting that they were stimulated and are likely to be antigen specific. It is unknown, however, whether cytotoxic T lymphocytes are important for protection, compared to antibody responses. The relative importance of the adaptive immune compartments might be dependent on the vaccine platform as well as the time between vaccination and exposure to Nipah virus. As neutralizing antibody concentrations might wane over time, memory T cell responses (CD4+ and/or CD8+) might prove important for contributing to protection. The observation that we detect CD8+ T cell effector responses, and these cells express IFNγ and granzyme B, after vaccination and challenge suggests that our platform induces a cellular memory response in addition to a rapid and robust humoral response. The measurement of T cell responses was done in a non-specific fashion by using PMA/ionomysin as a stimulus, so it is not possible to discern what percentage of T cells are specific for the G of Nipah virus verses the VSV backbone, or other activated T cells.

It this study we describe a vaccine approach that provides protection from Nipah virus replication and disease in the AGM model. The rapidity, potency, and complete protection demonstrated by our vaccine platform in general, and specifically the Nipah virus-specific platform presented herein, make it attractive as a candidate for use in outbreak situations. Although several outbreaks have been sporadic and involve single isolated cases, many have identifiable index cases and humans that come in contact with these individuals have developed disease weeks after contact with the index case, and the incubation period for this virus can extend for months or even years after exposure [13,34]. In these situations, a ring vaccination approach could prove efficacious, where family members, health care workers, and others that have the potential to contact the infected individuals could receive this vaccine to curtail disease and stop transmission.

Highlights.

Nipah virus causes severe human disease and there is no approved vaccine or therapeutic.

Attenuated VSV vaccines that express Nipah proteins are efficacious in African green monkeys.

A single administration prevents virus shedding, replication and Nipah virus disease.

The rapid time to immunity is advantageous in outbreak situations for ‘ring vaccination.’

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the Rocky Mountain Veterinary Branch for their care and handling of the animals. We also thank Anita Mora and Austin Athman (Visual Arts, NIAID, NIH) for graphics. This work was supported by the Division of Intramural Research of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest

The authors declare there is no conflict of interest.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Chua KB, Bellini WJ, Rota PA, Harcourt BH, Tamin A, Lam SK, et al. Nipah virus: a recently emergent deadly paramyxovirus. Science (80- ) 2000;288:1432–5. doi: 10.1126/science.288.5470.1432. 8529 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Goh KJ, Tan CT, Chew NK, Tan PS, Kamarulzaman A, Sarji SA, et al. Clinical features of Nipah virus encephalitis among pig farmers in Malaysia. N Engl J Med. 2000;342:1229–35. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200004273421701. MJBA-421701 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Quddus R, Alam S, Majumdar MA, Anwar S, Khan MR, Zahid Mahmud Khan AKS, et al. A report of 4 patients with Nipah encephalitis from Rajbari district, Bangladesh in the January 2004 Outbreak. Neurol Asia. 2004;9:33–7. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hsu VP, Hossain MJ, Parashar UD, Ali MM, Ksiazek TG, Kuzmin I, et al. Nipah virus encephalitis reemergence, Bangladesh. Emerg Infect Dis. 2004;10:2082–7. doi: 10.3201/eid1012.040701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Biswas T. Nipah Virus: Research Review of Infection Features and Recurrent Outbreaks. J Young Med Res. 2013;1:1. doi: 10.7869/jymr.10. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Field HE, Mackenzie JS, Daszak P. Henipaviruses: emerging paramyxoviruses associated with fruit bats. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 2007;315:133–59. doi: 10.1007/978-3-540-70962-6_7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Halpin K, Hyatt AD, Fogarty R, Middleton D, Bingham J, Epstein JH, et al. Pteropid bats are confirmed as the reservoir hosts of henipaviruses: a comprehensive experimental study of virus transmission. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2011;85:946–51. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.2011.10-0567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rahman MA, Hossain MJ, Sultana S, Homaira N, Khan SU, Rahman M, et al. Date palm sap linked to Nipah virus outbreak in Bangladesh, 2008. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis. 2012;12:65–72. doi: 10.1089/vbz.2011.0656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Luby SP, Hossain MJ, Gurley ES, Ahmed BN, Banu S, Khan SU, et al. Recurrent zoonotic transmission of Nipah virus into humans, Bangladesh, 2001–2007. Emerg Infect Dis. 2009;15:1229–35. doi: 10.3201/eid1508.081237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.ICDDRB. Person-to-person transmission of Nipah virus during outbreak in Faridpur District, 2004. Heal Sci Bull. 2004;2:5–9. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gurley ES, Montgomery JM, Hossain MJ, Bell M, Azad AK, Islam MR, et al. Person-to-person transmission of Nipah virus in a Bangladeshi community. Emerg Infect Dis. 2007;13:1031–7. doi: 10.3201/eid1307.061128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Luby SP, Gurley ES, Hossain MJ. Transmission of human infection with Nipah virus. Clin Infect Dis. 2009;49:1743–8. doi: 10.1086/647951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Homaira N, Rahman M, Hossain MJ, Epstein JH, Sultana R, Khan MS, et al. Nipah virus outbreak with person-to-person transmission in a district of Bangladesh, 2007. Epidemiol Infect. 2010;138:1630–6. doi: 10.1017/S0950268810000695. S0950268810000695 [pii] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chong HT, Kunjapan SR, Thayaparan T, Tong J, Petharunam V, Jusoh MR, et al. Nipah encephalitis outbreak in Malaysia, clinical features in patients from Seremban. Can J Neurol Sci. 2002;29:83–7. doi: 10.1017/s0317167100001785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Suhailah Abdullah L-YC. Late-onset Nipah virus encephalitis 11 years after the initial outbreak: A case report. Neurol Asia. 2012;17:71–4. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Prescott J, de Wit E, Feldmann H, Munster VJ. The immune response to Nipah virus infection. Arch Virol. 2012;157:1635–41. doi: 10.1007/s00705-012-1352-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Debuysscher BL, Scott D, Marzi A, Prescott J, Feldmann H. Single-dose live-attenuated Nipah virus vaccines confer complete protection by eliciting antibodies directed against surface glycoproteins. Vaccine. 2014;32:2637–44. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2014.02.087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Brown KS, Safronetz D, Marzi A, Ebihara H, Feldmann H. Vesicular stomatitis virus-based vaccine protects hamsters against lethal challenge with Andes virus. J Virol. 2011;85:12781–91. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00794-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Geisbert TW, Daddario-DiCaprio KM, Hickey AC, Smith MA, Chan YP, Wang LF, et al. Development of an acute and highly pathogenic nonhuman primate model of Nipah virus infection. PLoS One. 2010;5:e10690. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0010690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.DeBuysscher BL, de Wit E, Munster VJ, Scott D, Feldmann H, Prescott J. Comparison of the pathogenicity of Nipah virus isolates from Bangladesh and Malaysia in the Syrian hamster. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2013;7:e2024. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0002024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.De Wit E, Bushmaker T, Scott D, Feldmann H, Munster VJ. Nipah virus transmission in a hamster model. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2011;5:e1432. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0001432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bossart KN, Rockx B, Feldmann F, Brining D, Scott D, LaCasse R, et al. A Hendra virus G glycoprotein subunit vaccine protects African green monkeys from Nipah virus challenge. Sci Transl Med. 2012;4:146ra107. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3004241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yoneda M, Georges-Courbot M-C, Ikeda F, Ishii M, Nagata N, Jacquot F, et al. Recombinant measles virus vaccine expressing the Nipah virus glycoprotein protects against lethal Nipah virus challenge. PLoS One. 2013;8:e58414. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0058414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bossart KN, Geisbert TW, Feldmann H, Zhu Z, Feldmann F, Geisbert JB, et al. A neutralizing human monoclonal antibody protects african green monkeys from hendra virus challenge. Sci Transl Med. 2011;3:105ra103. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3002901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Geisbert TW, Mire CE, Geisbert JB, Chan Y-P, Agans KN, Feldmann F, et al. Therapeutic treatment of nipah virus infection in nonhuman primates with a neutralizing human monoclonal antibody. Sci Transl Med. 2014;6:242ra82. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3008929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jones SM, Feldmann H, Ströher U, Geisbert JB, Fernando L, Grolla A, et al. Live attenuated recombinant vaccine protects nonhuman primates against Ebola and Marburg viruses. Nat Med. 2005;11:786–90. doi: 10.1038/nm1258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Geisbert TW, Daddario-Dicaprio KM, Geisbert JB, Reed DS, Feldmann F, Grolla A, et al. Vesicular stomatitis virus-based vaccines protect nonhuman primates against aerosol challenge with Ebola and Marburg viruses. Vaccine. 2008;26:6894–900. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2008.09.082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Garbutt M, Liebscher R, Wahl-Jensen V, Jones S, Moller P, Wagner R, et al. Properties of Replication-Competent Vesicular Stomatitis Virus Vectors Expressing Glycoproteins of Filoviruses and Arenaviruses. J Virol. 2004;78:5458–65. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.10.5458-5465.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Daddario-DiCaprio KM, Geisbert TW, Ströher U, Geisbert JB, Grolla A, Fritz EA, et al. Postexposure protection against Marburg haemorrhagic fever with recombinant vesicular stomatitis virus vectors in non-human primates: an efficacy assessment. Lancet. 2006;367:1399–404. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)68546-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Feldmann H, Jones SM, Daddario-DiCaprio KM, Geisbert JB, Ströher U, Grolla A, et al. Effective post-exposure treatment of Ebola infection. PLoS Pathog. 2007;3:e2. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.0030002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Geisbert TW, Daddario-DiCaprio KM, Williams KJN, Geisbert JB, Leung A, Feldmann F, et al. Recombinant vesicular stomatitis virus vector mediates postexposure protection against Sudan Ebola hemorrhagic fever in nonhuman primates. J Virol. 2008;82:5664–8. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00456-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tsuda Y, Safronetz D, Brown K, LaCasse R, Marzi A, Ebihara H, et al. Protective efficacy of a bivalent recombinant vesicular stomatitis virus vaccine in the Syrian hamster model of lethal Ebola virus infection. J Infect Dis. 2011;204 (Suppl):S1090–7. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jir379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Marzi A, Engelmann F, Feldmann F, Haberthur K, Shupert WL, Brining D, et al. Antibodies are necessary for rVSV/ZEBOV-GP-mediated protection against lethal Ebola virus challenge in nonhuman primates. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110:1893–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1209591110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Homaira N, Rahman M, Hossain MJ, Nahar N, Khan R, Podder G, et al. Cluster of Nipah virus infection, Kushtia District, Bangladesh, 2007. PLoS One. 2010;5:e13570. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0013570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]