Abstract

The role of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-β/δ (PPARβ/δ) in cancer remains contentious due in large part to divergent publications indicating opposing effects in different rodent and human cell culture models. During the past 10 years, some facts regarding PPARβ/δ in cancer have become clearer, while others remain uncertain. For example, it is now well accepted that (1) expression of PPARβ/δ is relatively lower in most human tumors as compared to the corresponding non-transformed tissue, (2) PPARβ/δ promotes terminal differentiation, and (3) PPARβ/δ inhibits pro-inflammatory signaling in multiple in vivo models. However, whether PPARβ/δ is suitable to target with natural and/or synthetic agonists or antagonists for cancer chemoprevention is hindered because of the uncertainty in the mechanism of action and role in carcinogenesis. Recent findings that shed new insight into the possibility of targeting this nuclear receptor to improve human health will be discussed.

Keywords: Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-β/δ, Cancer, Chemoprevention, Inflammation

Introduction

Shortly after the initial discovery of the nuclear receptor, peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-α (PPARα) [1], PPARβ/δ was identified [2, 3]. The physiological roles of PPARβ/δ were elusive, and it was not until 1999 that the first report suggesting that PPARβ/δ was involved with cancer was reported [4]. In this study, the authors suggested that PPARβ/δ was activated by cyclooxygenase II (COX-2)-derived metabolites and promoted tumorigenesis in the colon by increasing cell proliferation [4]. However, since this time, numerous studies have revealed related and different hypotheses resulting in contradictory views and considerable uncertainty surrounding PPARβ/δ and cancer (reviewed in [5–8, 9•]).

A number of mechanisms by which ligand activation of PPARβ/δ influence cancer have been postulated using animal and human models, with some gaining stronger weight of evidence than others (reviewed in [5–8, 9•]). The majority of these mechanisms are dependent on the relative expression of the receptor and include molecular changes that modulate cell cycle progression, programmed cell death, cell survival, immunomodulation, differentiation status, and senescence. The focus of this review is on recent advances made in the past 5 years that are beginning to clarify the feasibility and potential for targeting PPARβ/δ for cancer chemoprevention in humans.

Expression of PPARβ/δ in Non-transformed Tissues and Cancer

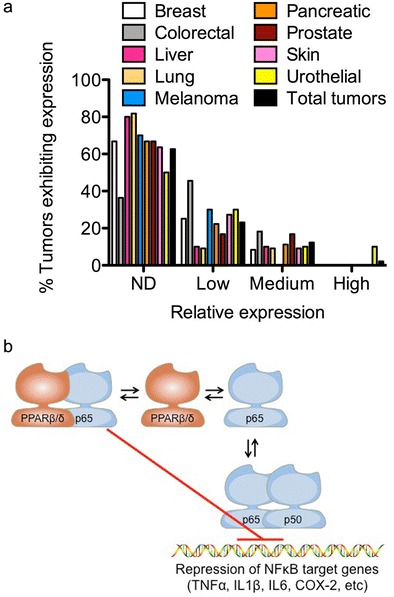

Quantitative expression patterns of PPARβ/δ have only recently been more precisely determined. For many years, relative expression of PPARβ/δ in human tissues remained obscure due in large part to the lack of highly quantitative approaches and the reliance on less quantitative methodology including simple assessments based primarily on messenger RNA (mRNA) expression (reviewed in [5–8, 9•]). Two publically available databases have been making large advances in elucidating the relative expression of PPARβ/δ in control non-transformed tissues and a variety of cancers. The Human Protein Atlas (www.proteinatlas.org) and Oncomine (www.oncomine.org) represent excellent resources for comparing the relative expression of both mRNA and protein [10••] or mRNA from microarray databases (Oncomine), respectively. Examination of these databases reveals that the expression of PPARβ/δ is relatively high in glandular cells found in the epithelial lining of the small intestine and the colon, glandular cells that compose the ductal cells of the breast, and respiratory epithelial cells in the nasopharynx in the lung, among other cell types in other tissues that also exhibit relatively high expression [10••]. By contrast, in tumor samples examined in The Human Protein Atlas to date (N = 192), the relative expression of PPARβ/δ is high to medium in only 2.1 or 12.3 % of all tumors examined, respectively, whereas the relative expression of PPARβ/δ is low to undetectable in 23.1 or 62.6 % of all tumors examined, respectively [10••]. While there is some variation in the relative expression between different tumor types (Fig. 1a), the majority of tumors examined in this database exhibited PPARβ/δ expression in only a fraction of the cells, while malignant cells were in general negative for the expression of PPARβ/δ [10••]. However, it is worth noting that testicular cancers, malignant gliomas, and lymphomas did exhibit relatively strong nuclear staining [10••]. In some cases, the findings observed in The Human Protein Atlas have also been confirmed using highly quantitative approaches including intestinal cancers where markedly reduced expression of PPARβ/δ is found in both human and mouse models [11, 12]. Furthermore, many proteins that can be regulated by PPARβ/δ are also found expressed at negligible to modestly low levels in cancers as compared to non-transformed tissues, including fatty acid-binding protein 1 (FABP1), FABP2, FABP3, FABP4, adipocyte differentiation-related protein, carnitine palmitoyltransferase 1A (CPT1A), CPT1C, and angiopoietin-like 4 [10••]. Results observed at the protein level have also been confirmed at the mRNA level in some cases. For example, the relative expression of PPARβ/δ is lower in human breast cancer samples (N = 12) based on analyses reported in The Human Protein Atlas [10••]. The Oncomine database revealed that expression of PPARβ/δ mRNA is also markedly reduced in human ductal breast adenocarcinomas as compared to normal tissue in three independent studies (P ≤ 0.003) [13, 14, 15•]. Thus, there are some consistencies in the literature indicating that the relative expression of PPARβ/δ is reduced in human cancers.

Fig. 1.

Expression of PPARβ/δ in human tumors and control tissue and mechanism of repression of pro-inflammatory signaling by PPARβ/δ. a Relative expression of protein based on analysis from the Human Protein Atlas on June 17, 2014, Version 12, Ensembl version 73.37. Relative expression is depicted as not detected (ND), low, medium, or high based on the parameters defined by the Human Protein Atlas. The total number of human tumors examined was 195. The total number of breast tumors examined was 12. The total number of colorectal tumors examined was 11. The total number of liver tumors examined was 10. The total number of lung tumors examined was 11. The total number of melanomas examined was 10. The total number of pancreatic tumors examined was 9. The total number of prostate tumors examined was 12. The total number of skin tumors examined was 11. The total number of urothelial tumors examined was 10. b PPARβ/δ can bind with the p65 subunit of NFκB and, by doing so, inhibit the ability of p65 to heterodimerize with the p50 subunit of NFκB, thereby inhibiting expression of NFκB target genes including TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6, COX-2, etc. This causes inhibition of pro-inflammatory signaling

In addition to the consistencies in the reduced expression of PPARβ/δ of different human tumors compared to normal tissue, several recent studies also support these observations. For example, a study examining human colorectal cancer patients revealed that higher expression of PPARβ/δ in primary colorectal tumors was associated with lower expression of a marker of relative cell proliferation (Ki67), a higher frequency of stage I cases in these patients, a lower frequency of later stage cases, and a lower rate of lymph node metastasis [16••]. Moreover, colorectal cancer patients with relatively low expression of PPARβ/δ were ~4 times more likely to die of colorectal cancer than those with a relatively higher expression of PPARβ/δ in primary tumors [16••]. For colon cancer, due in part to the relatively large number of patients examined (141) and the duration of the follow-up (~15 years), this is the best evidence to date supporting the view that PPARβ/δ has tumor suppressor activity. These findings are also similar to results observed in human colon cancer cell lines when expression of PPARβ/δ is knocked down. Reduced expression of PPARβ/δ in KM12C human colon cancer cells causes decreased differentiation and an increased tumor size of xenografts as compared to control xenografts from KM12C cells that express PPARβ/δ [17]. By contrast, another more limited study suggested that the survival of colorectal cancer patients was negatively correlated with expression of both PPARβ/δ and COX-2 in their tumors. Survival of 17 colorectal cancer patients whose tumor samples were positive for both PPARβ/δ and COX-2 expression, based on immunohistochemical analysis, was lower as compared with colorectal patients with tumors that appeared to express only PPARβ/δ, COX-2, or were not immunoreactive for PPARβ/δ and COX-2 [18]. This suggests that PPARβ/δ could cooperatively promote colorectal cancer via an undetermined mechanism that involved COX-2. However, this study has a number of limitations that prevents drawing firm conclusions, including (1) the total number of patients examined was low (52); (2) the follow-up was limited to less than 2 years; (3) the study relied on immunohistochemistry for estimating PPARβ/δ protein expression and correlating with survival, which has inherent problems and is not feasible (as discussed in previous papers [9•, 19]); (4) there was no comparison of patient survival for those with lower versus higher expression of PPARβ/δ alone; and (5) there was no comparison of survival for patients with different-stage disease whose tumors expressed COX-2 only, since this phenotype with early stage I tumors should survive longer than those exhibiting this phenotype with stages II–IV tumors [20]. Thus, there is actually accumulating evidence that the relatively higher expression of PPARβ/δ, similar to that found in normal colonic epithelial cells [10••], is protective against human colon cancer and that agonists that activate this receptor may prove to be chemopreventive for this disease.

A recent study using microarray analysis suggested that higher expression of PPARβ/δ is negatively associated with survival of breast cancer patients [21]. This negative correlation was independent of estrogen receptor (ER) status (i.e., the same effect was noted with ERα-negative and ERα-positive cancer patients), which is in contrast to previous work suggesting that activation of PPARβ/δ in ERα-positive, but not ERα-negative, human breast cancer cells caused increased cell proliferation [22]. However, this study has limitations that prevent drawing firm conclusions, including (1) the authors provide no indication how they defined “low,” “medium,” or “high” expression of PPARβ/δ mRNA; (2) the study relied on microarray mRNA expression data of PPARβ/δ from a separate study [23] that did not confirm differential mRNA expression and did not examine protein expression in the 295 patients; and (3) the data were not stratified to determine if there were differences in survival that could have been influenced by lymph node-negative disease, lymph node-positive disease, or whether there were differences in survival that were influenced by the use of chemotherapy, hormone therapy, or both chemotherapy and hormone therapy received by 130 of the 295 patients [21]. This study is also at odds with a recent report that examined the effect of over-expressing PPARβ/δ in ERα-negative and ERα-positive human breast cancer cells and found marked inhibition of cell growth, and inhibition of tumorigenicity in xenografts derived from either ERα-negative or ERα-positive human breast cancer cells, which was enhanced by ligand activation of PPARβ/δ compared to controls [24•]. Additionally, another recent study [21] is also inconsistent with previous work suggesting that higher expression of PPARβ/δ is negatively associated with breast cancer, because culturing MCF7 human breast cancer cells inhibits, but does not dose-dependently increase, proliferation in response to the ligand activation of PPARβ/δ by GW0742 [25]. Therefore, despite strong evidence that expression of PPARβ/δ is relatively high in glandular cells of human breast tissue, whether increased expression or decreased expression is prognostic for increased survival in humans remains unclear. However, the fact that expression is relatively high in this tissue as observed in the colon, and appears to decrease in human glandular breast tumors [10••] (Fig. 1a), argues against the notion that this protein could promote tumorigenesis. It is also worth noting that in some cells such as keratinocytes, ligand activation of PPARβ/δ can markedly increase its expression by directly increasing its own transcription [26]. Whether this occurs in other tissues and/or cells could also provide clues to the role of this receptor in carcinogenesis.

PPARβ/δ Promotes Terminal Differentiation

There are numerous reports that PPARβ/δ and ligands that activate PPARβ/δ can promote terminal differentiation. This has been shown in many different models including keratinocytes, intestinal epithelium, osteoblasts, oligodendrocytes, monocytes, and in colon, breast, and neuroblastoma cancer models (reviewed in [5–7, 9•, 27]). The mechanism(s) that mediate increased terminal differentiation by PPARβ/δ and ligands that activate PPARβ/δ include increased expression of gene products required for terminal differentiation and concomitant inhibition of cell proliferation and/or withdrawal from the cell cycle, effects that are not seen in cells lacking expression of PPARβ/δ (reviewed in [5–7, 9•, 27]). That PPARβ/δ promotes terminal differentiation has not been disputed to date. This is of particular interest because differentiation-inducing agents are known to be potentially useful for cancer chemoprevention [28] and/or cancer chemotherapy [29] due in part to their ability to induce cell cycle arrest [30] and/or enhance the effect of anti-cancer drugs [29], respectively.

The Anti-inflammatory Activities of PPARβ/δ

Similar to the role of PPARβ/δ in promoting terminal differentiation, it is well established that PPARβ/δ and ligand-activated PPARβ/δ can have potent anti-inflammatory activities in many disease models including cancer (reviewed in [8, 9•, 31–35]). This includes PPARβ/δ-dependent reductions in the expression of pro-inflammatory proteins including COX-2, TNF-α, interleukin 1β (IL-1β), and IL-6. It is also interesting to note that many pro-inflammatory mediators including TNF-α, phorbol esters, and others can all induce expression of PPARβ/δ [36, 37], possibly through an AP1 regulatory site in the promoter of the PPARβ/δ gene [37]. Does the known increase in expression of PPARβ/δ in response to pro-inflammatory signaling molecules mean that PPARβ/δ promotes inflammation? Quite the contrary; the collective evidence generated in the past 10 years indicates otherwise. There are more than 100 studies to date showing that PPARβ/δ and ligands that activate PPARβ/δ can have potent anti-inflammatory activities in numerous rodent and human disease models (reviewed in [8, 9•, 31–35]). Many independent laboratories have reproduced these effects. This suggests that the reason why pro-inflammatory cytokines such as TNF-α, or those released in response to phorbol ester, increase expression of PPARβ/δ is to counteract the effects of the inflammatory response and potentially lead to resolution of the inflammatory signaling. Indeed, the hypothesis that increased expression and/or activation of PPARβ/δ counteracts the effects of the inflammatory response and causes resolution of inflammatory signaling was postulated in 2008 [7]. Evidence supporting this hypothesis is provided by studies demonstrating that over-expression of PPARβ/δ and/or ligand activation of PPARβ/δ in rat macrophages markedly inhibits lipopolysaccharide-induced expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines including TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-6 as compared to controls [38]. Further, resolution of inflammation has also been observed by simple administration of the PPARβ/δ ligand GW0742 in an ischemia/reperfusion model of tissue injury [39]. In contrast to more than 100 studies using rodent and human models reported by multiple laboratories, a recent paper suggested that ligand activation of PPARβ/δ induces COX-2 expression in mouse colon [40], similar to the reported increase in COX-2 expression observed in human liver cancer cell lines following treatment with a PPARβ/δ ligand [41, 42]. However, other studies found no change in colonic COX-2 expression in mice by ligand activation of PPARβ/δ [43] and no change in expression of COX-2 in human liver cancer cell lines in response to ligand activation of PPARβ/δ [44]. In fact, ligand activation of PPARβ/δ in mouse macrophages or microglial cells, and rat cardiomyocytes, vascular smooth muscle cells, and cardiomyocytes prevents induced expression of COX-2 in these cell types [45–49]. Thus, despite some conflicting evidence, there is an overwhelming amount of studies demonstrating that PPARβ/δ inhibits pro-inflammatory signaling (reviewed in [8, 9•, 31–35]), and thus could serve as a cancer chemopreventive target.

The mechanism by which PPARβ/δ inhibits pro-inflammatory signaling has been primarily attributed to attenuation of nuclear factor kappa beta (NFκB) signaling (Fig. 1b). This mechanism has been reviewed extensively [8, 9•, 31–35]. Interestingly, all three isoforms of PPARs show some common modes of action for inhibiting inflammation. Moreover, there are additional mechanisms by which PPARβ/δ may inhibit pro-inflammatory signaling (reviewed in [8, 9•, 31–35]). For example, it was recently shown that reducing acetylation of the p65 subunit of NFκB in a human keratinocyte cell line via interactions with AMP kinase and SIRT1 can prevent activation of NFκB following treatment with TNF-α, in response to ligand activation of PPARβ/δ [50]. Whether this and other mechanisms described for PPARs can be used as targets for cancer chemoprevention has not been explored sufficiently. This is of interest to point out because there is evidence that blocking TNF-α signaling [51, 52], COX-2 signaling [53], and/or IL-1β [54, 55] may be suitable for cancer chemoprevention.

Contemporary Controversies

There are many examples of putative mechanisms mediated by PPARβ/δ in cancer models in which different laboratories have reported opposing results (reviewed in [5–8, 9•]). Reproducibility of mechanistic studies is a problem for all areas of research, which has led to discontinuation of the development of numerous drugs and carries a large cost [56••, 57, 58••, 59]. As noted above, in studies on the role of PPARβ/δ in cancer, there are many examples where reproducibility between laboratories remains an ongoing problem. In some cases, scientific error may be the cause of the lack of reproducibility. For example, it was postulated that all-trans retinoic acid activated PPARβ/δ and promoted tumorigenesis due to the increased expression of a putative target gene, 3-phosphoinositide-dependent protein kinase-1 (PDPK1) [60]. However, at least two independent laboratories failed to reproduce these findings, despite extensive approaches that included the use of the same cell type (HaCaT keratinocytes), but also various experiments that should have derived comparable data supporting this putative mechanism [61–63]. These disparities remain unclear, and to date, no other laboratories have ever reported that this mechanism, does or does not, function in HaCaT keratinocytes. There are many other examples of mechanisms that have been described for PPARβ/δ but have not been reproduced by other laboratories (reviewed in [5–8, 9•]). Thus, the targeting of PPARβ/δ for cancer chemoprevention has been hampered because it is not entirely clear that an agonist, an antagonist, or both, would be suitable for cancer chemoprevention. This is indeed disappointing given the nature of nuclear receptors and the fact that PPARs are typically a nodal target that could potentially affect multiple signaling pathways. The targeting of a nodal target such as a PPAR has advantages because targeting single proteins for cancer chemoprevention has proven ineffective [64].

The development of compounds that target PPARβ/δ has also been negatively influenced by alleged scientific misconduct [65••]. For example, Han and colleagues published several manuscripts describing the effects of ligand activation of PPARβ/δ in human lung cancer cell lines that have caused great confusion in this field. The first study reported that ligand activation of PPARβ/δ increased the expression of the prostaglandin E2 receptor subtype EP4 via phosphatidylinositide 3-kinase (PI3)/protein kinase B (AKT) signaling in human lung cancer cells [66]. A second study reported that ligand activation of PPARβ/δ increased proliferation of human lung cancer cells via downregulation of the tumor suppressor phosphatase and tensin homolog (PTEN) that was also mediated by PI3/AKT signaling [67]. A third paper from this group suggested that ligand activation of PPARβ/δ increased proliferation of human lung cancer cells via interactions with peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor coactivator γ-1α [68]. Subsequently, the publisher retracted one of these published manuscripts in June 2011, along with two other manuscripts focusing on the effects of fibronectin in lung cells [69–71]. In this case, while the retraction notice did not provide an explanation, another peer-reviewed report indicated that these manuscripts were retracted because of alleged scientific fraud [65••]. Additionally, the other two papers published by Han and colleagues reporting effects of ligand activation of PPARβ/δ in human lung cancer cells were also retracted in 2012, and the retraction notices indicated that data presented in the original articles were either manipulated and/or duplicated in other publications [72, 73]. Interestingly, a follow-up manuscript published by another group indicated that ligand activation of PPARβ/δ had no effect on PTEN or AKT expression and did not increase proliferation of two human lung cancer cell lines [74] as initially reported by Han and colleagues [67]. Despite the fact that the three articles describing the effects of ligand activation of PPARβ/δ in human lung cancer cell lines [66–68] were retracted between July 2011 and May 2012, the retracted articles continue to be cited in the literature to support contentions made by others in their own peer-reviewed papers [75–83]. This illustrates the need for investigators in this field to be cognizant of retracted articles and use caution when using references to support their own research publications. This also highlights a problem that exists not only in the field of PPARβ/δ research but others as well.

Conclusions

The expression of PPARβ/δ is high in many tissues such as colon, breast, and lung epithelium. This is highly inconsistent with the hypothesis that PPARβ/δ promotes tumorigenesis. In contrast, there is strong evidence from multiple laboratories supporting a higher level of reproducibility of studies showing that PPARβ/δ promotes terminal differentiation and inhibits pro-inflammatory signaling. These collective observations argue strongly that PPARβ/δ functions as a tumor suppressor, rather than a tumor promoter. However, considerable research remains before the precise roles of this nuclear receptor in physiology, diseases, and cancer will be elucidated.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the National Institutes of Health (CA124533, CA141029, CA140369, AA018863) (J.M.P.) and the National Cancer Institute Intramural Research Program (ZIABC005561, ZIABC005562, ZIABC005708) (F.J.G.).

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

ᅟ

Conflict of Interest

Jeffrey M. Peters, Pei-Li Yao, and Frank J. Gonzalez declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Human and Animal Rights and Informed Consent

This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

Footnotes

This article is part of the Topical Collection on Cancer Chemoprevention

References

Papers of particular interest, published recently, have been highlighted as follows: • Of importance •• Of major importance

- 1.Issemann I, Green S. Activation of a member of the steroid hormone receptor superfamily by peroxisome proliferators. Nature. 1990;347(6294):645–50. doi: 10.1038/347645a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dreyer C, Krey G, Keller H, Givel F, Helftenbein G, Wahli W. Control of the peroxisomal beta-oxidation pathway by a novel family of nuclear hormone receptors. Cell. 1992;68(5):879–87. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90031-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kliewer SA, Forman BM, Blumberg B, Ong ES, Borgmeyer U, Mangelsdorf DJ, et al. Differential expression and activation of a family of murine peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1994;91(15):7355–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.15.7355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.He TC, Chan TA, Vogelstein B, Kinzler KW. PPARδ is an APC-regulated target of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. Cell. 1999;99(3):335–45. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)81664-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Peters JM, Foreman JE, Gonzalez FJ. Dissecting the role of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-β/δ (PPARβ/δ) in colon, breast and lung carcinogenesis. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2011;30(3–4):619–40. doi: 10.1007/s10555-011-9320-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Peters JM, Gonzalez FJ. Sorting out the functional role(s) of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-β/δ (PPARβ/δ) in cell proliferation and cancer. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2009;1796(2):230–41. doi: 10.1016/j.bbcan.2009.06.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Peters JM, Hollingshead HE, Gonzalez FJ. Role of peroxisome-proliferator-activated receptor β/δ (PPARβ/δ) in gastrointestinal tract function and disease. Clin Sci (Lond) 2008;115(4):107–27. doi: 10.1042/CS20080022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Peters JM, Morales JL, Gonzales FJ. Modulation of gastrointestinal inflammation and colorectal tumorigenesis by peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-β/δ (PPARβ/δ) Drug Discov Today: Dis Mech. 2011;8(3–4):e85–93. doi: 10.1016/j.ddmec.2011.11.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.•.Peters JM, Shah YM, Gonzales FJ. The role of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors in carcinogenesis and chemoprevention. Nat Rev Cancer. 2012;12(3):181–95. doi: 10.1038/nrc3214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.••.Uhlen M, Oksvold P, Fagerberg L, Lundberg E, Jonasson K, Forsberg M, et al. Towards a knowledge-based human protein atlas. Nat Biotechnol. 2010;28(12):1248–50. doi: 10.1038/nbt1210-1248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Foreman JE, Chang WC, Palkar PS, Zhu B, Borland MG, Williams JL, et al. Functional characterization of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-β/δ expression in colon cancer. Mol Carcinog. 2011;50(11):884–900. doi: 10.1002/mc.20757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Modica S, Gofflot F, Murzilli S, D’Orazio A, Salvatore L, Pellegrini F, et al. The intestinal nuclear receptor signature with epithelial localization patterns and expression modulation in tumors. Gastroenterology. 2010;138(2):636–48. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2009.09.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Perou CM, Sorlie T, Eisen MB, van de Rijn M, Jeffrey SS, Rees CA, et al. Molecular portraits of human breast tumours. Nature. 2000;406(6797):747–52. doi: 10.1038/35021093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sorlie T, Perou CM, Tibshirani R, Aas T, Geisler S, Johnsen H, et al. Gene expression patterns of breast carcinomas distinguish tumor subclasses with clinical implications. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98(19):10869–74. doi: 10.1073/pnas.191367098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.•.Sorlie T, Tibshirani R, Parker J, Hastie T, Marron JS, Nobel A, et al. Repeated observation of breast tumor subtypes in independent gene rexpression data sets. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100(14):8418–23. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0932692100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.••.Yang L, Zhang H, Zhou ZG, Yan H, Adell G, Sun XF. Biological function and prognostic significance of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor δ in rectal cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2011;17(11):3760–70. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-2779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yang L, Zhou J, Ma Q, Wang C, Chen K, Meng W, et al. Knockdown of PPAR δ gene promotes the growth of colon cancer and reduces the sensitivity to bevacizumab in nude mice model. PLoS ONE. 2013;8(4):e60715. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0060715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yoshinaga M, Taki K, Somada S, Sakiyama Y, Kubo N, Kaku T, et al. The expression of both peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor δ and cyclooxygenase-2 in tissues is associated with poor prognosis in colorectal cancer patients. Dig Dis Sci. 2011;56(4):1194–200. doi: 10.1007/s10620-010-1389-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Foreman JE, Sorg JM, McGinnis KS, Rigas B, Williams JL, Clapper ML, et al. Regulation of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-β/δ by the APC/β-CATENIN pathway and nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs. Mol Carcinog. 2009;48(10):942–52. doi: 10.1002/mc.20546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sheehan KM, Sheahan K, O’Donoghue DP, MacSweeney F, Conroy RM, Fitzgerald DJ, et al. The relationship between cyclooxygenase-2 expression and colorectal cancer. JAMA. 1999;282(13):1254–7. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.13.1254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kittler R, Zhou J, Hua S, Ma L, Liu Y, Pendleton E, et al. A comprehensive nuclear receptor network for breast cancer cells. Cell Rep. 2013;3(2):538–51. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2013.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Stephen RL, Gustafsson MC, Jarvis M, Tatoud R, Marshall BR, Knight D, et al. Activation of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor δ stimulates the proliferation of human breast and prostate cancer cell lines. Cancer Res. 2004;64(9):3162–70. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-03-2760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chang HY, Nuyten DS, Sneddon JB, Hastie T, Tibshirani R, Sorlie T, et al. Robustness, scalability, and integration of a wound-response gene expression signature in predicting breast cancer survival. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102(10):3738–43. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0409462102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.•.Yao PL, Morales JL, Zhu B, Kang BH, Gonzalez FJ, Peters JM. Activation of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-β/δ (PPAR-β/δ) inhibits human breast cancer cell line tumorigenicity. Mol Cancer Ther. 2014;13(4):1008–17. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-13-0836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Girroir EE, Hollingshead HE, Billin AN, Willson TM, Robertson GP, Sharma AK, et al. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-β/δ (PPARβ/δ) ligands inhibit growth of UACC903 and MCF7 human cancer cell lines. Toxicology. 2008;243(1–2):236–43. doi: 10.1016/j.tox.2007.10.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Khozoie C, Borland MG, Zhu B, Baek S, John S, Hager GL, et al. Analysis of the peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-β/δ (PPARβ/δ) cistrome reveals novel co-regulatory role of ATF4. BMC Genomics. 2012;13665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 27.Burdick AD, Kim DJ, Peraza MA, Gonzalez FJ, Peters JM. The role of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-β/δ in epithelial cell growth and differentiation. Cell Signal. 2006;18(1):9–20. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2005.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.De Flora S, Ferguson LR. Overview of mechanisms of cancer chemopreventive agents. Mutat Res. 2005;591(1–2):8–15. doi: 10.1016/j.mrfmmm.2005.02.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kawamata H, Tachibana M, Fujimori T, Imai Y. Differentiation-inducing therapy for solid tumors. Curr Pharm Des. 2006;12(3):379–85. doi: 10.2174/138161206775201947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Buttitta LA, Edgar BA. Mechanisms controlling cell cycle exit upon terminal differentiation. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2007;19(6):697–704. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2007.10.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bility MT, Devlin-Durante MK, Blazanin N, Glick AB, Ward JM, Kang BH, et al. Ligand activation of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-β/δ (PPARβ/δ) inhibits chemically-induced skin tumorigenesis. Carcinogenesis. 2008;29(12):2406–14. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgn219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Coll T, Barroso E, Alvarez-Guardia D, Serrano L, Salvado L, Merlos M, et al. The role of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor β/δ on the inflammatory basis of metabolic disease. PPAR Res. 2010;2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 33.Kilgore KS, Billin AN. PPARβ/δ ligands as modulators of the inflammatory response. Curr Opin Investig Drugs. 2008;9(5):463–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mandard S, Patsouris D. Nuclear control of the inflammatory response in mammals by peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors. PPAR Res. 2013;2013613864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 35.Wahli W, Michalik L. PPARs at the crossroads of lipid signaling and inflammation. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2012;23(7):351–63. doi: 10.1016/j.tem.2012.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Matsuura H, Adachi H, Smart RC, Xu X, Arata J, Jetten AM. Correlation between expression of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor β and squamous differentiation in epidermal and tracheobronchial epithelial cells. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 1999;147(1–2):85–92. doi: 10.1016/S0303-7207(98)00214-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tan NS, Michalik L, Noy N, Yasmin R, Pacot C, Heim M, et al. Critical roles of PPARβ/δ in keratinocyte response to inflammation. Genes Dev. 2001;15(24):3263–77. doi: 10.1101/gad.207501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wang C, Zhou G, Zeng Z. Effects of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-β/δ on sepsis induced acute lung injury. Chin Med J (Engl) 2014;127(11):2129–37. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Di Paola R, Esposito E, Mazzon E, Paterniti I, Galuppo M, Cuzzocrea S. GW0742, a selective PPAR-β/δ agonist, contributes to the resolution of inflammation after gut ischemia/reperfusion injury. J Leukoc Biol. 2010;88(2):291–301. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0110053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wang D, Fu L, Ning W, Guo L, Sun X, Dey SK, et al. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor δ promotes colonic inflammation and tumor growth. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2014;111(19):7084–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1324233111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Glinghammar B, Skogsberg J, Hamsten A, Ehrenborg E. PPARδ activation induces COX-2 gene expression and cell proliferation in human hepatocellular carcinoma cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2003;308(2):361–8. doi: 10.1016/S0006-291X(03)01384-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Xu L, Han C, Lim K, Wu T. Cross-talk between peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor {δ} and cytosolic phospholipase A2{α}/cyclooxygenase-2/prostaglandin E2 signaling pathways in human hepatocellular carcinoma cells. Cancer Res. 2006;66(24):11859–68. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-1445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hollingshead HE, Borland MG, Billin AN, Willson TM, Gonzalez FJ, Peters JM. Ligand activation of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-β/δ (PPARβ/δ) and inhibition of cyclooxygenase 2 (COX2) attenuate colon carcinogenesis through independent signaling mechanisms. Carcinogenesis. 2008;29(1):169–76. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgm209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hollingshead HE, Killins RL, Borland MG, Girroir EE, Billin AN, Willson TM, et al. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-β/δ (PPARβ/δ) ligands do not potentiate growth of human cancer cell lines. Carcinogenesis. 2007;28(12):2641–9. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgm183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kapoor A, Collino M, Castiglia S, Fantozzi R, Thiemermann C. Activation of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-β/δ attenuates myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury in the rat. Shock. 2010;34(2):117–24. doi: 10.1097/SHK.0b013e3181cd86d6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ravaux L, Denoyelle C, Monne C, Limon I, Raymondjean M, El Hadri K. Inhibition of interleukin-1β-induced group IIA secretory phospholipase A2 expression by peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors (PPARs) in rat vascular smooth muscle cells: cooperation between PPARβ and the proto-oncogene BCL-6. Mol Cell Biol. 2007;27(23):8374–87. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00623-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Schnegg CI, Kooshki M, Hsu FC, Sui G, Robbins ME. PPARδ prevents radiation-induced proinflammatory responses in microglia via transrepression of NF-κB and inhibition of the PKCα/MEK1/2/ERK1/2/AP-1 pathway. Free Radic Biol Med. 2012;52(9):1734–43. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2012.02.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Smeets PJ, Teunissen BE, Planavila A, de Vogel-van den Bosch H, Willemsen PH, van der Vusse GJ, et al. Inflammatory pathways are activated during cardiomyocyte hypertrophy and attenuated by PPARα and PPARδ. J Biol Chem. 2008;283(43):29109–18. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M802143200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Welch JS, Ricote M, Akiyama TE, Gonzalez FJ, Glass CK. PPARγ and PPARδ negatively regulate specific subsets of lipopolysaccharide and IFN-gamma target genes in macrophages. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100(11):6712–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1031789100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Barroso E, Eyre E, Palomer X, Vazquez-Carrera M. The peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor β/δ (PPARβ/δ) agonist GW501516 prevents TNF-α-induced NF-κB activation in human HaCaT cells by reducing p65 acetylation through AMPK and SIRT1. Biochem Pharmacol. 2011;81(4):534–43. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2010.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Onizawa M, Nagaishi T, Kanai T, Nagano K, Oshima S, Nemoto Y, et al. Signaling pathway via TNF-α/NF-κB in intestinal epithelial cells may be directly involved in colitis-associated carcinogenesis. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2009;296(4):G850–9. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00071.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Popivanova BK, Kitamura K, Wu Y, Kondo T, Kagaya T, Kaneko S, et al. Blocking TNF-α in mice reduces colorectal carcinogenesis associated with chronic colitis. J Clin Invest. 2008;118(2):560–70. doi: 10.1172/JCI32453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Fischer SM, Hawk ET, Lubet RA. Coxibs and other nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs in animal models of cancer chemoprevention. Cancer Prev Res (Phila) 2011;4(11):1728–35. doi: 10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-11-0166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Li Y, Wang L, Pappan L, Galliher-Beckley A, Shi J. IL-1β promotes stemness and invasiveness of colon cancer cells through Zeb1 activation. Mol Cancer. 2012;1187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 55.Zhu Y, Zhu M, Lance P. IL1β-mediated Stromal COX-2 signaling mediates proliferation and invasiveness of colonic epithelial cancer cells. Exp Cell Res. 2012;318(19):2520–30. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2012.07.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.••.Arrowsmith J. Trial watch: phase II failures: 2008–2010. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2011;10(5):328–9. doi: 10.1038/nrd3439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Begley CG, Ellis LM. Drug development: raise standards for preclinical cancer research. Nature. 2012;483(7391):531–3. doi: 10.1038/483531a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.••.Collins FS, Tabak LA. Policy: NIH plans to enhance reproducibility. Nature. 2014;505(7485):612–3. doi: 10.1038/505612a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Prinz F, Schlange T, Asadullah K. Believe it or not: how much can we rely on published data on potential drug targets? Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2011;10(9):712. doi: 10.1038/nrd3439-c1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Schug TT, Berry DC, Shaw NS, Travis SN, Noy N. Opposing effects of retinoic acid on cell growth result from alternate activation of two different nuclear receptors. Cell. 2007;129(4):723–33. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.02.050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Borland MG, Foreman JE, Girroir EE, Zolfaghari R, Sharma AK, Amin SM, et al. Ligand activation of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-β/δ (PPARβ/δ) inhibits cell proliferation in human HaCaT keratinocytes. Mol Pharmacol. 2008;74(5):1429–42. doi: 10.1124/mol.108.050609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Borland MG, Khozoie C, Albrecht PP, Zhu B, Lee C, Lahoti TS, et al. Stable over-expression of PPARβ/δ and PPARγ to examine receptor signaling in human HaCaT keratinocytes. Cell Signal. 2011;23(12):2039–50. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2011.07.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Rieck M, Meissner W, Ries S, Muller-Brusselbach S, Muller R. Ligand-mediated regulation of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor (PPAR) β/δ: a comparative analysis of PPAR-selective agonists and all-trans retinoic acid. Mol Pharmacol. 2008;74(5):1269–77. doi: 10.1124/mol.108.050625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Hanahan D, Weinberg RA. Hallmarks of cancer: the next generation. Cell. 2011;144(5):646–74. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.••.Fang FC, Steen RG, Casadevall A. Misconduct accounts for the majority of retracted scientific publications. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109(42):17028–33. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1212247109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Han S, Ritzenthaler JD, Wingerd B, Roman J. Activation of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor β/δ (PPARβ/δ) increases the expression of prostaglandin E2 receptor subtype EP4. The roles of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase and CCAAT/enhancer-binding protein β. J Biol Chem. 2005;280(39):33240–9. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M507617200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Han S, Ritzenthaler JD, Zheng Y, Roman J. PPARβ/δ agonist stimulates human lung carcinoma cell growth through inhibition of PTEN expression: the involvement of PI3K and NF-κB signals. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2008;294(6):L1238–49. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00017.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Han S, Ritzenthaler JD, Sun X, Zheng Y, Roman J. Activation of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor β/δ induces lung cancer growth via peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor coactivator γ-1α. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2009;40(3):325–31. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2008-0197OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 69.Han S, Ritzenthaler JD, Sitaraman SV, Roman J. Retraction: fibronectin increases matrix metalloproteinase 9 expression through activation of c-Fos via extracellular-regulated kinase and phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase pathways in human lung carcinoma cells. J Biol Chem. 2006;286(28):25416. doi: 10.1074/jbc.A111.604013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Han S, Ritzenthaler JD, Wingerd B, Rivera HN, Roman J. Retraction: extracellular matrix fibronectin increases prostaglandin E receptor subtype EP4 in lung carcinoma cells through multiple signaling pathways: the role of AP-2. J Biol Chem. 2007;286(28):25416. doi: 10.1074/jbc.A111.610308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Han S, Ritzenthaler JD, Wingerd B, Roman J: Retraction. Activation of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor β/δ (PPARβ/δ) increases the expression of prostaglandin E2 receptor subtype EP4. The roles of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase and CCAAT/enhancer-binding protein β. J Biol Chem. 2011; 286(28):25416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 72.Han S, Ritzenthaler JD, Sun X, Zheng Y, Roman J. Retraction: activation of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor β/δ induces lung cancer growth via peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor coactivator γ-1α. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2012;46(3):414. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2008-0197OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 73.Han S, Ritzenthaler JD, Zheng Y, Roman J. Retraction: PPARβ/δ agonist stimulates human lung carcinoma cell growth through inhibition of PTEN expression: the involvement of PI3K and NF-κB signals. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2012;302(9):L976. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.zh5-6122-retr.2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.He P, Borland MG, Zhu B, Sharma AK, Amin S, El-Bayoumy K, et al. Effect of ligand activation of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-β/δ (PPARβ/δ) in human lung cancer cell lines. Toxicology. 2008;254:112–7. doi: 10.1016/j.tox.2008.09.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Bovee TF, Blokland M, Kersten S, Hamers AR, Heskamp HH, Essers ML, et al. Bioactivity screening and mass spectrometric confirmation for the detection of PPARδ agonists that increase type 1 muscle fibres. Anal Bioanal Chem. 2014;406(3):705–13. doi: 10.1007/s00216-013-7520-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Genini D, Garcia-Escudero R, Carbone GM, Catapano CV. Transcriptional and non-transcriptional functions of PPARβ/δ in Non-small cell lung cancer. PLoS ONE. 2012;7(9):e46009. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0046009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Huang Y, Li J, Garcia JM, Lin H, Wang Y, Yan P, et al. Phthalate levels in cord blood are associated with preterm delivery and fetal growth parameters in Chinese women. PLoS ONE. 2014;9(2):e87430. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0087430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Kim HJ, Ham SA, Kim MY, Hwang JS, Lee H, Kang ES, et al. PPARδ coordinates angiotensin II-induced senescence in vascular smooth muscle cells through PTEN-mediated inhibition of superoxide generation. J Biol Chem. 2011;286(52):44585–93. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.222562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Kogai T, Brent GA. The sodium iodide symporter (NIS): regulation and approaches to targeting for cancer therapeutics. Pharmacol Ther. 2012;135(3):355–70. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2012.06.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Pagliei B, Aquilano K, Baldelli S, Ciriolo MR. Garlic-derived diallyl disulfide modulates peroxisome proliferator activated receptor γ co-activator 1 α in neuroblastoma cells. Biochem Pharmacol. 2013;85(3):335–44. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2012.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Wu HT, Chen W, Cheng KC, Ku PM, Yeh CH, Cheng JT. Oleic acid activates peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor δ to compensate insulin resistance in steatotic cells. J Nutr Biochem. 2012;23(10):1264–70. doi: 10.1016/j.jnutbio.2011.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Yuan H, Lu J, Xiao J, Upadhyay G, Umans R, Kallakury B, et al. PPARδ induces estrogen receptor-positive mammary neoplasia through an inflammatory and metabolic phenotype linked to mTOR activation. Cancer Res. 2013;73(14):4349–61. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-13-0322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Yang Y, Burke RV, Jeon CY, Chang SC, Chang PY, Morgenstern H, Tashkin DP, Mao J, Cozen W, Mack TM, et al.: Polymorphisms of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors and survival of lung cancer and upper aero-digestive tract cancers. Lung Cancer 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]