Abstract

Surfactin, one of the most effective biosurfactants, has great potential in commercial applications. Studies on effective methods to reduce surfactin’s production cost are always a hotspot in the research field of biosurfactants. The aim of this study was to reveal the role of Mn2+ in promoting the biosynthesis of surfactin by Bacillus subtilis ATCC 21332, which could arise more targeted suggestions on surfactin yield promotion. In this study, B. subtilis was cultivated in media containing different Mn2+ concentrations. The obtained results showed that the yield of surfactin gradually increased upon Mn2+ addition (0.001 to 0.1 mmol/L) and achieved the maximal production of 1500 mg/L, which reached 6.2-fold of the yield obtained in media without Mn2+ addition. Correspondingly, the usage ratios of ammonium nitrate were improved. When the Mn2+ concentration was higher than 0.05 mmol/L, nitrate became the main nitrogen source, instead of ammonium, indicating that the nitrogen utilization pattern was also changed. An increase in nitrate reductase activity was observed and the increase upon Mn2+ dosage had a positive correlate with nitrate use, and then stimulated secondary metabolic activity and surfactin synthesis. On the other hand, Mn2+ enhanced the glutamate synthase activity, which increased nitrogen absorption and transformation and provided more free amino acids for surfactin synthesis.

Keywords: Bacillus subtilis, surfactin, Mn2+, enzyme activity, nitrogen metabolism

Introduction

Biosurfactants are surface-active compounds, produced by a variety of micro-organisms.[1–3] Because of their high biodegradability, low toxicity and high efficiency, biosurfactants are of increasing interest as possible alternative to chemical surfactants.[4,5] Based on their chemical composition, biosurfactants can be categorized into five groups, which include glycolipids, lipopeptides, phospholipids, fatty acids and polymeric biosurfactants.[6–8] Surfactin, which belongs to lipopeptides group, produced by Bacillus subtilis, is recognized as one of the most effective biosurfactants.[9] It consists of a heptapeptide head group attached to a lactone ring by a beta-hydroxy fatty acid.[10] As it can reduce the surface tension to 27 mN/m at concentration as low as 0.005%,[9,11–14] surfactin has a great potential in commercial applications.[15] However, its high production costs and low yield limit its commercial use. Medium improvement is one of the most common and effective approaches to promote surfactin production.[9,16]

Methods for medium improvement mainly involve optimization of the carbon source,[17–19] nitrogen source [20–23] and promoting factors. This includes selection of nutrient species and optimization of their concentrations and dosing. As one of the most important promoting factors, metal ions have attracted attention for their ability to enhance surfactin yields. Of the most commonly investigated metal ions, which are Mn2+, Cu2+, Co2+, Mg2+, Ni2+, Fe2+, Ca2+, Al3+ and Zn2+, Mn2+ has shown to be one of the metal ions that can promote surfactin yield significantly.[24–27] Studies have shown that the addition of Mn2+ shortened the cycle duration in continuous-phased growth of B. subtilis [28] and increased its surfactin productivity in batch cultures.[27] Wei and Chu speculated that changes in nitrogen usage and K+ uptake were the reasons for the promotion of surfactin synthesis by Mn2+.[27] However, these studies only focused on changes in the surfactin yield, but none of them studied the mechanisms which are directly responsible for the influence of Mn2+ on surfactin yield enhancement.

Sheppard and Cooper reported an intimate relationship between the availability of Fe2+ and Mn2+ and the usage of nitrogen.[28] The essential role of amino acids as precursors of the heptapeptide head group of surfactin makes nitrogen metabolism very important for the surfactin biosynthesis by B. subtilis. Davis et al. found that when B. subtilis was cultivated in a defined medium with ammonium nitrate as the nitrogen source, the surfactin production was highest when B. subtilis used nitrate, causing the subsequent onset of nitrate-limited growth.[29] Mn2+ is the most important trace metal element for the growth of some species of Bacillus and fungi, and it can function as a cofactor for many enzymes involved in nitrogen metabolism.[30] When B. subtilis is cultivated in media with ammonium nitrate as the nitrogen source, nitrogen assimilation includes the usage of NH4 + and NO3 −. Before the assimilation of NO3 −, it must be transformed into NO2 − and then into NH4 +.[31] This process is limited by the first step reaction, which is catalyzed by nitrate reductase (NR).[32] For B. subtilis, assimilation and transformation of NH4 + into an organic form primarily occurs through the coupled reactions catalyzed by glutamine synthetase (GS) and glutamate synthase (GOGAT)[33]

| (1) |

| (2) |

This process is the only pathway for glutamine and glutamate synthesis and ammonium assimilation in B. subtilis’ cells.[34] Thus, the three enzymes are crucial to nitrogen metabolism, growth and reproduction of B. subtilis.

In this study, we cultivated B. subtilis in media with different initial Mn2+ concentrations and then monitored the growth characteristics, surfactin production, carbon and nitrogen usage characteristics and activities of the enzymes, which are involved in nitrogen assimilation. Taken together, we hoped that the results would help to reveal the mechanism that is responsible for the influence of Mn2+ on the biosynthesis of surfactin by B. subtilis.

Materials and methods

Micro-organisms and culture conditions

B. subtilis ATCC 21332 was obtained from the American Type Culture Collection. The strain was maintained on an agar slant at 4 °C and transferred monthly.

B. subtilis ATCC 21332 was cultured in agar plate at 30 °C for two days, then inoculated into 100 mL nutrient broth in 250-mL flasks and incubated on a gyratory shaker at 200 rpm for 12–14 h at 30 °C. For the preparation of the next seed culture, 5 mL of the cultured medium were inoculated into 100 mL of fresh medium. This seed culture was incubated for 10 h at 200 rpm at 30 °C before inoculating 1 mL from it into a 500-mL flask, which contained 200 mL of fermentation medium with different concentrations of Mn2+. The fermentation medium flasks were incubated under the same conditions as the seed culture, for six days. The composition of the three media was as follows: the nutrient broth contained 10 g/L NaCl, 5 g/L yeast extract and 10 g/L fish peptone; the seed and fermentation media were based on the mineral salt medium reported by Cooper et al.[26] The seed medium contained 40 g/L glucose, 50 mmol/L NH4NO3, 30 mmol/L Na2HPO4, 30 mmol/L KH2PO4, 7 μmol/L CaCl2 and 4 μmol/L ethylene diamine tetraacetic acid disodium (Na-EDTA). The composition of the fermentation medium contained all the components of the seed medium with three additional components, including 0.8 mmol/L MgSO4, 4 μmol/L FeSO4 and a certain concentration of MnSO4 (0, 0.001, 0.005, 0.05 and 0.1 mmol/L, respectively).

Analysis of enzyme activities

Preparation of cell extracts

After centrifugation of culture samples (19800 × g, 10 min, 4 °C), the cell pellets were washed twice with distilled water, once with phosphate buffer (pH 7.7) and then re-suspended in buffer to remove surfactant that would interfere with the subsequent enzyme analyses. The cell suspensions were mixed with glass beads (diameter 0.1 mm) and disrupted using the bead-milling method (3000 rpm, 5 min). Cell debris was removed by centrifugation (13750 × g, 15 min, 4 °C). The supernatants were stored at 30 °C in a water bath and used as crude enzyme for enzyme assays.

Analysis of glutamine synthetase

The biosynthetic activity of GS was measured at 30 °C by detecting the production of a red complex produced by the interaction of Fe3+ with γ-glutamylhydroxamate, as described by Shapiro and Stadtman.[35] The GS activity was expressed in terms of the absorbance of the solution at 540 nm. The control group had buffer instead of crude enzyme in the reaction.

Analysis of nitrate reductase and glutamate synthase

NR and GOGAT were assayed spectrophotometrically by measuring reduced nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NADH) oxidation at 340 nm (ΔOD/min) as described by Berges and Harrison [36] and Meers et al.,[37] respectively. For this purpose, 0.6 mL of crude enzyme was added into 2.4 mL of the reaction system A, which contained 80.2 mmol/L K2HPO4, 19.8 mmol/L KH2PO4, 100 mmol/L KNO3 and 0.2 mmol/L NADH and maintained for 3 min to determine the NR activity. Next, 0.6 mL of crude enzyme was added into 2.4 mL of the reaction system B, which contained 20 mmol/L Tris-HCl (pH 7.0), 1 mmol/L α-ketoglutaric acid, 15 mmol/L L-glutamine and 0.1 mmol/L NADH and maintained for 3 min to determine the GOGAT activity. The temperature of the spectrophotometer (UV-8000; Shanghai Yuanxi Instruments Ltd., Shanghai, China) was maintained at 30 °C during the assays. The concentration of protein was detected using Coomassie brilliant blue. The NR and GOGAT activities were obtained from the following equation:

| (3) |

Equation (3) takes into account the NADH oxidation at 340 nm (ΔOD/min), the total reaction volume (Vt, mL), the crude enzyme volume (Vs, mL), the dilution factor (DF) and the protein concentration of crude enzyme (C, mg/L).

Analysis methods

Determination of biomass

Samples were centrifuged (19800 × g, 4 °C) for 10 min. The pellet was suspended in distilled water and re-centrifuged. The biomass was determined by weighing after drying by vacuum lyophilization at −50 °C for 24 h.

Quantitative analysis of surfactin

The concentration of surfactin was determined by using a reverse-phase, high-performance liquid chromatograph (HPLC), (Waters Alliance2695-2489, Waters, USA) equipped with a C18-WR column (5 μm, 250 × 4.6 mm). To determine the concentration of surfactin, culture samples were withdrawn aseptically and centrifuged at 13,750 × g for 10 min to pellet the cells. The supernatant was dried by vacuum lyophilization at −50 °C for 24 h and re-dissolved in methanol in order to avoid contamination by saline ions. The methanol solution of surfactin was filtered through a 0.45-μm membrane and quantified by HPLC. The mobile phase was 0.05% trifluoroacetic acid/acetonitrile (1/9, v/v) at 0.5 mL/min with a column temperature of 35 °C and a sample size of 20 μL. The absorbance of the eluent was monitored at 205 nm. Surfactin purchased from Sigma (St. Louis, MO, USA) served as a standard.

Determination of glucose, nitrite, nitrate and ammonium

Culture samples were centrifuged (19,800 × g, 4 °C) for 10 min to pellet the cells. The supernatant was used for direct glucose determination. In order to determine the concentration of nitrite, nitrate and ammonium, the supernatant was acidified to pH < 2.0 with sulphuric acid (10%, v/v) and centrifuged at 19,800 × g for 10 min to remove the precipitated surfactant.

Glucose was determined by using 3,5-dinitrosalicylic acid. The content of nitrate was determined by UV spectrophotometry. The concentration of nitrite was determined by using N-(1-naphthyl)-ethylenediamine spectrophotometry. The concentration of ammonium was determined by H2SO4 titration after distillation on a Kjeldahl determination device (K9840; Hanon Instruments Ltd, Nanjing, China). Instrument parameters were 50 mL boric acid (2%), 10 mL sodium hydroxide (40%), 6-min distillation time and 40-mL water wash.

Results and discussion

Biomass and surfactin production in media with different concentrations of Mn2+

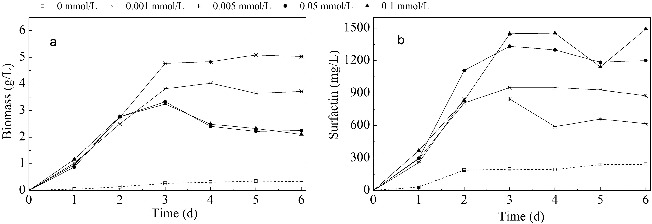

The biomass and surfactin concentrations during the cultivation are shown in Figure 1. Improved cell growth and increased surfactin production were observed in media with included Mn2+. Initially, the biomass concentration increased before its increment when the Mn2+ concentration became above 0.005 mmol/L. The highest biomass was obtained when the concentration of Mn2+ was 0.005 mmol/L, which was 11.4 times more than that of the control group and with 50% more than the biomass in media with higher concentrations of Mn2+ (0.05 and 0.1 mmol/L). Thus, media containing lower concentrations (0.001 and 0.005 mmol/L) of Mn2+ were better for B. subtilis cell growth. With the increase of Mn2+ dosage, the surfactin concentration was enhanced. The highest yield was 1500 mg/L when the concentration of Mn2+ was 0.1 mmol/L, which was 6.2 times more than that of the control group and 1.5 times more than that of the groups with lower Mn2+ concentrations (0.001 and 0.005 mmol/L). Therefore, it can be concluded that the higher concentrations of Mn2+ (0.05 and 0.1 mmol/L) were better for the production of surfactin from B. subtilis strain.

Figure 1.

Biomass and surfactin production in media with different concentrations of Mn2+. Note: Biomass concentration (a); surfactin concentration (b).

It is clear that the addition of Mn2+ can significantly improve the growth of B. subtilis and the production of surfactin. In the study of Wei and Chu,[27] the biomass and surfactin yield were increased by 3-folds and 6.9-folds, respectively, with 0.01 mmol/L Mn2+ concentration. In this study, the two parameters were increased by 7-folds and 5.2-folds, respectively, with a Mn2+ concentration of 0.1 mmol/L. The production of surfactin by B. subtilis has been observed to be closely related to cell growth.[38] However, different trends of cell growth and surfactin production have been observed when Mn2+ concentration increased. As described by Sheppard and Cooper,[28] the cycle duration and CMC−1 (dilution factor of the free-cell fermentation broth that corresponds to the critical micelle concentration [26]) of the fermentation broth changed from 90 min and 7 to 180 min and 8, respectively, when the Mn2+ concentration increased from 0.03 to 0.3 mmol/L, which indicated that with the increase of the Mn2+ concentration, the rate of growth decreased by half, but the yield of surfactin increased slightly. In this study, when the Mn2+ concentration was above 0.005 mmol/L (including 0.005 mmol/L), the biomass concentration decreased, while the surfactin concentration increased. Similar results have also been reported in studies, where other metal ions like Ca2+, Fe2+, K+ and Mg2+ were added as promoting factors.[24,39] One of the possible reasons may be that some enzymes have two metal binding sites which have different affinity to the metal ions. At different concentrations, alterations in the configuration and activity of the enzyme (protein) may be observed, depending on whether the binding sites are occupied.[40] More changes in exact metabolic processes and enzymatic activities that related to surfactin synthesis, due to the addition of different concentrations of Mn2+, will be discussed in details below.

Usage of glucose and ammonium nitrate in media with different concentrations of Mn2+

Usage of glucose

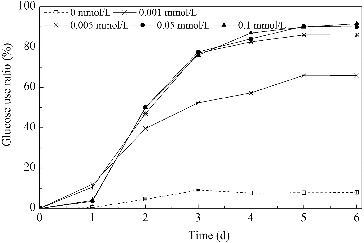

In this study, B. subtilis was cultivated in media with glucose as the carbon source at an initial concentration of 40 g/L. The usage ratio of glucose, under different concentrations of Mn2+, is shown in Figure 2. Nutrition absorption, cell growth and surfactin production took place during the first three days of the cultivation period. The addition of Mn2+ promoted the usage of glucose significantly. When the Mn2+ concentration was 0.001 mmol/L, the usage ratio was 66%, which was nine times more than that of the control, but lower than the other three groups. At the other three concentrations of Mn2+, the glucose usage ratio was essentially constant -- at about 85%, reaching 11.6 times more than that of the control group. These results indicated that the glucose usage of B. subtilis improved significantly in the presence of low Mn2+ concentrations, but failed to further improve when the Mn2+ concentration was higher than 0.005 mmol/L.

Figure 2.

Usage of glucose in media with different concentrations of Mn2+.

Usage of ammonium nitrate

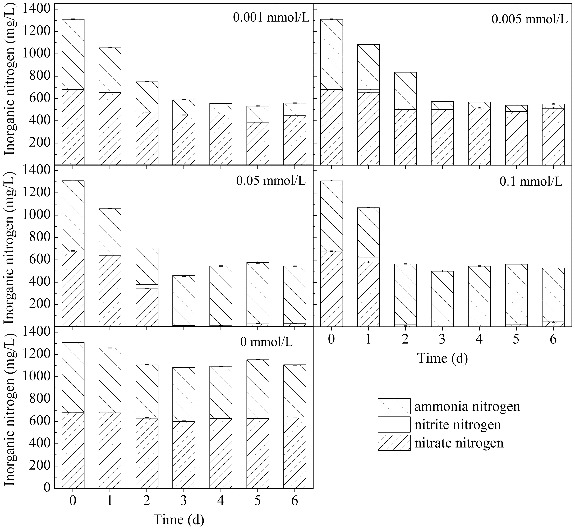

Ammonium nitrate was used as the nitrogen source in this study. The use of ammonium nitrate under the influence of different concentrations of Mn2+ is shown in Figure 3. The usage ratio of the total inorganic nitrogen was about 60% in the media with Mn2+ (nitrogen concentration was stabilized at around 540 mg/L) compared with 16% for the control. Similar to the glucose use ratios, very little difference was observed between the four nitrogen usage ratios for the media with different Mn2+ concentrations. When the Mn2+ concentration was 0.005, 0.05 and 0.1 mmol/L, the surfactin yield rose gradually while the usage of carbon and nitrogen remained relatively stable. This phenomenon indicated that a bigger amount of the carbon and nitrogen nutrition, assimilated by B. subtilis, goes for surfactin synthesis as the Mn2+ concentration increased.

Figure 3.

Changes in the concentration of ammonium nitrate in media with different concentrations of Mn2+.

Ammonium nitrate consists of NH4 + and NO3 −, both of which can be assimilated by B. subtilis. As shown in Figure 3, the usage of NH4 + and NO3 − is totally different, depending on the concentration of Mn2+ (0.001–0.1 mmol/L) in the medium, although the usage ratio of ammonium nitrate was similar among the different conditions. For groups with lower Mn2+ concentrations (0.001 and 0.005 mmol/L), the NH4 + usage of B. subtilis improved from 25% of the control group to 93%, while the NO3 − usage ratio only increased from 12% to 34%. Thus, NH4 + was found to be the main nitrogen source adsorbed by B. subtilis from these media. For groups grown in the presence of higher Mn2+ concentrations (0.05 and 0.1 mmol/L), the NO3 − usage ratio increased and reached 100% in three days after the start of the cultivation and as a result, the primary form of nitrogen, assimilated by B. subtilis, was shifted to NO3 −. The decline of NH4 + was much slower, and even had a tendency to slightly increase after a two-day cultivation. In addition, during the usage of nitrate, tens of milligrams of nitrite per litre were detected. An increase of about 100 mg/L in ammonium were also detected in media with 0.05 and 0.1 mmol/L Mn2+ from two to four and from one to two days, respectively.

Micro-organisms’ nitrogen utilization is dramatically influenced by metal ions in the culture medium. Kim et al. [41] reported that the isolated Kle b siella pneumoniae F-5-2 can utilize 100% NH4 + and 30% NO3 − in 24 h. When 0.1 mmol/L Fe2+ was added to the medium, both NH4 + and NO3 − were exhausted simultaneously in the culture within six hours of incubation. Zhou et al. [42] found that Zn2+, Mn2+, Fe2+ and Fe3+ markedly improved the usage of nitrogen source by Pseudomonas aeruginosa NBRC 12389. What’s more, Zn2+ and Mn2+ only improved the utilization ratio of NH4 + (from 35% to 90%), while Fe2+ and Fe3+ improved the utilization ratios of NH4 + and NO3 −, simultaneously (from 35% and 5% to 98% and 100%, respectively). Compared with the study of Sheppard and Cooper,[28] the present research focused on the influence of Mn2+ on the utilization of ammonium and nitrate, simultaneously. The results showed that with the addition of Mn2+, the usage of nitrogen source increased significantly by B. subtilis. The utilization of NO3 − was increased when the dosage of Mn2+ increased and it turned to the main nitrogen source instead of NH4 + in the cultivation of B. subtilis. The mechanism of the influence of metal ions on nitrogen use has not been revealed by now. One possible influence pathway is that the metal ions, added into the medium, stimulated and changed the activities of enzymes in the nitrogen metabolism process. Thus, we studied the relationship between Mn2+ and the key enzymes in nitrogen metabolism in the following.

In addition, as shown in Figure 1, a higher NH4 + usage ratio and biomass concentration were obtained in media with lower Mn2+ concentrations (0.001 and 0.005 mmol/L), while a higher NO3 − use ratio and higher surfactin production were obtained in media with higher Mn2+ concentrations (0.05 and 0.1 mmol/L). These results indicated that the use of NH4 + was better for B. subtilis cell growth and the use of NO3 − was better for enhancing surfactin synthesis in the presence of Mn2+. The results reported by Davis et al. supported our observations.[29] Under defined nutrition limited conditions, only 53.2 mg/L surfactin were obtained in cultures containing only ammonium, while in media containing only nitrate as the nitrogen source, poor growth was obtained (biomass concentration was 1.2–1.4 g/L). In cultures with both ammonium and nitrate, the surfactin concentration increased and reached a maximum when nitrate use occurred, causing the subsequent onset of nitrate-limited growth (surfactin concentration was 439 mg/L). One possible reason may be that due to the shorter assimilation pathway of ammonium, B. subtilis may prefer this nitrogen source, rather than nitrate, in order to support its own growth. However, the production of surfactin was enhanced when nitrate became the growth-limiting nutrient and the use of this nitrogen source may have been a switching signal to a secondary metabolism that promoted the synthesis of surfactin, as a secondary metabolite.[29,34]

To sum up, the addition of Mn2+ significantly changed the nitrogen metabolism of B. subtilis. The usage of NH4 + and NO3 − were both promoted at the same time. The NO3 − usage ability of B. subtilis was improved as the Mn2+ concentration increased, making nitrate the main nitrogen source instead of ammonium and a nitrate-limited growth, which led to the enhancement of the production of surfactin.

Activities of enzymes in nitrogen assimilation in media with different concentrations of Mn2+

Based on the above analysis, nitrogen usage and surfactin synthesis by B. subtilis were closely related in the presence of Mn2+, which suggested that the enzymes involved in nitrogen assimilation require further study.

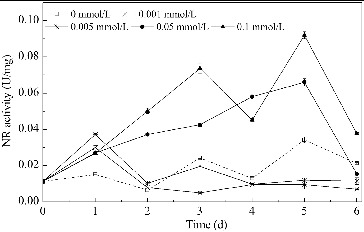

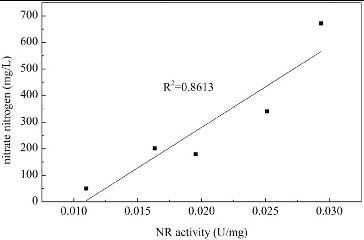

NR activity

The changes in NR activity over time in media with different concentrations of Mn2+ are shown in Figure 4. The NR activity of B. subtilis generally increased upon Mn2+ addition. In media with lower Mn2+ concentrations (0.001 and 0.005 mmol/L), the NR activity increased over the first two days, but then decreased to a relatively low level. In media with higher Mn2+ concentrations (0.05 and 0.1 mmol/L), the NR activity was significantly increased over the first five days. As shown in Figure 3, nitrate was mainly absorbed by B. subtilis over the first two days. Figure 5 shows that a significant positive correlation was observed between the nitrate usage and the NR activity over the first two days (α < 0.05). This indicates that the usage of nitrate is determined by the NR activity in media with Mn2+ as a promoting factor. This is because the step catalyzed by NR is the first and the speed-limiting step of the nitrate usage process.[32] It has also been reported that Mn2+ stimulated the activity of NR in Clostridium perfringens and with an addition of 0.1 mmol/L Mn2+, the NR activity improved by 58%.[43] For B. subtilis in this study, the addition of Mn2+ enhanced the NR activity, which directly improved the nitrate use and created a nitrate-limited condition, which could promote the production of surfactin.

Figure 4.

Changes in NR activity over time in media with different concentrations of Mn2+. Note: NR activity is expressed as micromoles of NADH oxidized per minute per milligram of protein.

Figure 5.

Correlation of NR activity and usage of nitrate nitrogen. Note: NR activity is expressed as micromoles of NADH oxidized per minute per milligram of protein.

GS and GOGAT activities

Changes in GS and GOGAT activities over time in media with different concentrations of Mn2+ are shown in Figure 6. In the first three days, GS activity first increased and then decreased during the cultivation. GS activity in the four media with Mn2+ was 50%–75% higher than that in the control medium, but the activities did not differ greatly from each other. This fits well with the observation that nitrogen usage in the four media with varying Mn2+ concentrations was similar in the different media, but higher than the control medium. In addition, the GS activity in media with higher Mn2+ concentrations (0.05 and 0.1 mmol/L) was at a low level after the third day, which coincided with the termination of nitrogen usage. The increase of the GS activity in the other three media after three days was unexpected, and the reason remained unclear. In general, the GS activity was promoted by Mn2+ addition but was not influenced by changes in Mn2+ concentration. Martinez-Espinosa et al. [44] also found that Mn2+ provoked an increase of the activity of the purified GS (purified from Haloferax mediterranei) at a concentration of 1 mmol/L due to its essential role as a cofactor.

Figure 6.

Changes in GS and GOGAT activities over time in media with different concentrations of Mn2+. Note: GS activity is expressed as absorption values increased per hour per milligram of protein. GOGAT activity is expressed as micromoles of NADH oxidized per minute per milligram of protein.

As shown in Figure 6(b), Mn2+ had a stronger influence on GOGAT activity than on GS activity. The GOGAT activity was significantly higher in media with Mn2+ than in the control medium. The GOGAT activity was enhanced as the Mn2+ concentration increased. The highest activity was about 4.6 times more than that of the control medium on the third day at 0.1 mmol/L Mn2+. The GOGAT activity was maintained for a longer time in media with higher Mn2+ concentrations (0.05 and 0.1 mmol/L) than in media with lower Mn2+ concentrations (0.001 and 0.005 mmol/L). The GOGAT activity of B. subtilis was influenced by the ammonium content. The expression of gltAB encoding the GOGAT protein may be suppressed by the pleiotropic regulator TnrA in the absence of ammonium,[45] resulting in a lower cellular GOGAT activity. At lower Mn2+ concentrations (0.001 and 0.005 mmol/L), ammonium was used as the main nitrogen source and as the cultivation time increased, the ammonium decreased, finally reaching a concentration of 38 mg/L (see Figure 3). This may explain the decrease of GOGAT activity in media with lower Mn2+ concentrations (0.001 and 0.005 mmol/L).

On the whole, the presence of Mn2+ increased the activity of the nitrogen utilization and conversion enzyme system of B. subtilis. On one hand, the activity of NR was enhanced as the Mn2+ concentration increased, which also improved the use of nitrate and ammonium. The use of nitrate further promoted the synthesis of surfactin by increasing the secondary metabolism and led to a nitrate-limited growth, which was beneficial to the enhancement of surfactin production.[29] On the other hand, Mn2+ promoted nitrogen metabolism and transformation by increasing the GOGAT activity, which produced more free amino acids. The heptapeptide head group of surfactin is made up of seven amino acids,[10] thus an abundant free amino acid content is preferred by the surfactin synthesis process. It can be deduced that the presence of Mn2+ improved the synthesis of surfactin by influencing the nitrogen metabolism of B. subtilis.

Conclusion

In this study, the role of Mn2+in promoting B. subtilis’ surfactin synthesis and substrate use was investigated from the perspective of metabolic enzymes’ activities. The addition of Mn2+ significantly improved the surfactin production by influencing the ammonium nitrate usage and the activity of the enzymes in nitrogen assimilation. This study showed an intimate relationship between nitrogen metabolism and surfactin biosynthesis in details, under the influence of Mn2+. It can be inferred that other convenient ways in industrial processes that can influence the nitrogen use of B. subtilis may also be effective in promoting surfactin yield, such as controlling the carbon nitrogen ratio and adding a moderate concentration of free amino acids in the medium.

Acknowledgements

The high-performance liquid chromatograph was kindly provided by the research group of pollution prevention and control in process of the College of Environmental Science and Technology, Tongji University. We do appreciate their kindness.

Funding Statement

This work was supported by the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities [grant number 0400219208]; the National Natural Science Foundation of China [grant number 51108333].

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

- Muthusamy K. Gopalakrishnan S. Ravi TK. Sivachidambaram P. Biosurfactants: properties, commercial production and application. Curr Sci India. 2008;94(6):736–747. [Google Scholar]

- Banat IM. Characterization of biosurfactants and their use in pollution removal – state of the art. Acta Biotechnol. 1995;15(3):251–267. [Google Scholar]

- Youssef NH. Duncan KE. Nagle DP. Savage KN. Knapp RM. McInerney MJ. Comparison of methods to detect biosurfactant production by diverse microorganisms. J Microbiol Methods. 2004;56(3):339–347. doi: 10.1016/j.mimet.2003.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banat IM. Franzetti A. Gandolfi I. Bestetti G. Martinotti MG. Fracchia L. Smyth TJ. Marchant R. Microbial biosurfactants production, applications and future potential. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2010;87(2):427–444. doi: 10.1007/s00253-010-2589-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawniczak L. Marecik R. Chrzanowski L. Contributions of biosurfactants to natural or induced bioremediation. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2013;97(6):2327–2339. doi: 10.1007/s00253-013-4740-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mukherjee AK. Das K. Microbial surfactants and their potential applications: an overview. In: Sen R, editor. Biosurfactants. Vol. 672, Advances in experimental medicine and biology. New York: Springer; 2010. pp. 54–64. editor. NY. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mulligan CN, editor; Mudhoo A, editor; Sharma SK, editor. Biosurfactants: research trends and applications. Boca Raton: CRC Press Inc; 2014. FL. [Google Scholar]

- Christova N. Lang S. Wray V. Kaloyanov K. Konstantinov S. Stoineva I. Production, structural elucidation and in vitro antitumor activity of trehalose lipid biosurfactant from Nocardia farcinica strain. J Microbiol Biotechn [Internet]. doi: 10.4014/jmb.1406.06025. http://www.jmb.or.kr/journal/paper_list.html?key=title&keyword=Production%2C+structural+elucidation+and+in+vitro+antitumor+activity+of+trehalose+lipid+biosurfactant+from+Nocardia+farcinica+strain [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaligram NS. Singhal RS. Surfactin – a review on biosynthesis, fermentation, purification and applications. Food Technol Biotechnol. 2010;48:119–134. [Google Scholar]

- Liu JF. Yang J. Yang SZ. Ye RQ. Mu BZ. Effects of different amino acids in culture media on surfactin variants produced by Bacillus subtilis TD7. Appl Biochem Biotechnol. 2012;166:2091–2100. doi: 10.1007/s12010-012-9636-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abdel-Mawgoud AM. Aboulwafa MM. Hassouna NAH. Characterization of surfactin produced by Bacillus subtilis isolate BS5. Appl Biochem Biotechnol. 2008;150:289–303. doi: 10.1007/s12010-008-8153-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arima K. Kakinuma A. Tamura G. Surfactin, a crystalline peptide lipid surfactant produced by Bacillus subtilis: isolation, characterization and its inhibition of fibrin clot formation. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1968;31(3):488–494. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(68)90503-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mulligan CN. Chow TYK. Gibbs BF. Enhanced biosurfactant production by a mutant Bacillus subtilis strain. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 1989;31:486–489. [Google Scholar]

- Khan MS, editor; Zaidi A, editor; Goel R, editor; Musarrat J, editor. Biomanagement of metal-contaminated soils. Vol. 20, Environmental pollution. Dordrecht: Springer; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Campos JM. Stamford TLM. Sarubbo LA. de Luna JM. Rufino RD. Banat IM. Microbial biosurfactants as additives for food industries. Biotechnol Prog. 2013;29:1097–1108. doi: 10.1002/btpr.1796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deleu M. Paquot M. From renewable vegetables resources to microorganisms: new trends in surfactants. Comptes Rendus Chimie. 2004:641–646. [Google Scholar]

- Sousa M. Melo VMM. Rodrigues S. Sant'ana HB. Goncalves LRB. Screening of biosurfactant-producing Bacillus strains using glycerol from the biodiesel synthesis as main carbon source. Bioprocess Biosyst Eng. 2012;35:897–906. doi: 10.1007/s00449-011-0674-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yanez-Mendizabal V. Vinas I. Usall J. Torres R. Solsona C. Teixido N. Production of the postharvest biocontrol agent Bacillus subtilis CPA-8 using low cost commercial products and by-products. Biol Control. 2012;60:280–289. [Google Scholar]

- de Sousa M. Dantas IT. Felix AKN. de Sant'Ana HB. Melo VMM. Goncalves LRB. Crude glycerol from biodiesel industry as substrate for biosurfactant production by Bacillus subtilis ATCC 6633. Braz Arch Biol Technol. 2014;57:295–301. [Google Scholar]

- Pereira JFB. Gudina EJ. Costa R. Vitorino R. Teixeira JA. Coutinho JAP. Rodrigues LR. Optimization and characterization of biosurfactant production by Bacillus subtilis isolates towards microbial enhanced oil recovery applications. Fuel. 2013;111:259–268. [Google Scholar]

- Vagvolgyi C. Sajben-Nagy E. Boka B. Voros M. Berki A. Palagyi A. Krisch J. Skrbic B. Durisic-Mladenovic N. Manczinger L. Isolation and characterization of antagonistic Bacillus strains capable to degrade ethylenethiourea. Curr Microbiol. 2013;66:243–250. doi: 10.1007/s00284-012-0263-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim J. Isolation and characterization of a biosurfactant-producing bacterium Bacillus pumilus IJ-1 from contaminated crude oil collected in Taean, Korea. J Korean Soc Appl Biol Chem. 2014;57:5–14. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao PC. Quan CS. Jin LM. Wang LN. Wang JH. Fan SD. Effects of critical medium components on the production of antifungal lipopeptides from Bacillus amyloliquefaciens Q-426 exhibiting excellent biosurfactant properties. World J Microbiol Biotechnol. 2013;29:401–409. doi: 10.1007/s11274-012-1180-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei Y. Lai C. Chang J. Using Taguchi experimental design methods to optimize trace element composition for enhanced surfactin production by Bacillus subtilis ATCC 21332. Process Biochem. 2007;42:40–45. [Google Scholar]

- Abdel-Mawgoud AM. Aboulwafa MM. Hassouna NAH. Optimization of surfactin production by Bacillus subtilis isolate BS5. Appl Biochem Biotechnol. 2008;150:305–325. doi: 10.1007/s12010-008-8155-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper DG. Macdonald CR. Duff SJ. Kosaric N. Enhanced production of surfactin from Bacillus subtilis by continuous product removal and metal cation additions. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1981;42:408–412. doi: 10.1128/aem.42.3.408-412.1981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei Y. Chu I. Mn2+ improves surfactin production by Bacillus subtilis . Biotechnol Lett. 2002;24:479–482. [Google Scholar]

- Sheppard JD. Cooper DG. The response of Bacillus subtilis atcc 21332 to manganese during continuous-phased growth. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 1991;35:72–76. [Google Scholar]

- Davis D. Lynch H. Varley J. The production of surfactin in batch culture by Bacillus subtilis atcc 21332 is strongly influenced by the conditions of nitrogen metabolism. Enzym Microb Technol. 1999;25:322–329. [Google Scholar]

- Pettit RK. Small-molecule elicitation of microbial secondary metabolites. Microb Biotechnol. 2011;4:471–478. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-7915.2010.00196.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slivinski CT. Mallmann E. de Araújo JM. Mitchell DA. Krieger N. Production of surfactin by Bacillus pumilus UFPEDA 448 in solid-state fermentation using a medium based on okara with sugarcane bagasse as a bulking agent. Process Biochem. 2012;47:1848–1855. [Google Scholar]

- Karsh KL. Granger J. Kritee K. Sigman DM. Eukaryotic assimilatory nitrate reductase fractionates N and O isotopes with a ratio near unity. Environ Sci Technol. 2012;46:5727–5735. doi: 10.1021/es204593q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wacker I. Ludwig H. Reif I. Blencke H-M. Detsch C. Stülke J. The regulatory link between carbon and nitrogen metabolism in Bacillus subtilis: regulation of the gltAB operon by the catabolite control protein CcpA. Microbiology. 2003;149:3001–3009. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.26479-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher SH. Regulation of nitrogen metabolism in Bacillus subtilis: Vive la différence! Mol Microbiol. 1999;32:223–232. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1999.01333.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shapiro BM. Stadtman E. Glutamine synthetase (Escherichia coli) Methods Enzymol. 1970;17:910–922. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(85)13032-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berges JA. Harrison P. Nitrate reductase activity quantitatively predicts the rate of nitrate incorporation under steady state light limitation: a revised assay and characterization of the enzyme in three species of marine phytoplankton. Limnology Oceanography. 1995;40:82–93. [Google Scholar]

- Meers J. Tempest D. Brown C. ‘Glutamine (amide): 2-oxoglutarate amino transferase oxido-reductase (NADP)’, an enzyme involved in the synthesis of glutamate by some bacteria. J Gen Microbiol. 1970;64:187–194. doi: 10.1099/00221287-64-2-187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei Y. Wang L. Chang J. Optimizing iron supplement strategies for enhanced surfactin production with Bacillus subtilis . Biotechnol Prog. 2004;20:979–983. doi: 10.1021/bp030051a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Makkar R. Cameotra S. Effects of various nutritional supplements on biosurfactant production by a strain of Bacillus subtilis at 45°C. J Surfactants Detergents. 2002;5:11–17. [Google Scholar]

- Weinberg ED. Roles of trace metals in transcriptional control of microbial secondary metabolism. Biol Metals. 1990;2:191–196. doi: 10.1007/BF01141358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim Y. Yoshizawa M. Takenaka S. Murakami S. Aoki K. Isolation and culture conditions of a K l ebsiella pneumoniae strain that can utilize ammonium and nitrate ions simultaneously with controlled iron and molybdate ion concentrations. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem. 2002;66:996–1001. doi: 10.1271/bbb.66.996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou Q. Takenaka S. Murakami S. Seesuriyachan P. Kuntiya A. Aoki K. Screening and characterization of bacteria that can utilize ammonium and nitrate ions simultaneously under controlled cultural conditions. J Biosci Bioeng. 2007;103:185–191. doi: 10.1263/jbb.103.185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seki-Chiba S. Ishimoto M. Studies on nitrate reductase of Clostridium perfringens. Purification, some properties, and effect of tungstate on its formation. J Biochem. 1977;82(6):1663–1671. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a131862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez-Espinosa RM. Esclapez J. Bautista V. Bonete MJ. An octameric prokaryotic glutamine synthetase from the haloarchaeon Haloferax mediterranei . FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2006;264:110–116. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2006.00434.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belitsky BR. Wray LV. Fisher SH. Bohannon DE. Sonenshein AL. Role of TnrA in nitrogen source-dependent repression of Bacillus subtilis glutamate synthase gene expression. J Bacteriol. 2000;182:5939–5947. doi: 10.1128/jb.182.21.5939-5947.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]