Abstract

It has long been accepted that psychological factors adversely influence efforts to optimise glycaemic control. These are often unrecognised in terms of clinical assessment and therefore under reported. This essay presents an introduction to psychological issues that interact with psychiatric co-morbidities and diabetes-specific distress, and a case scenario illustrating the interconnectedness of presenting problems and themes. In the way that we cannot separate carbohydrate counting, blood glucose monitoring and insulin dose adjustment in the understanding of a presenting problem such as poor control, so we cannot separate the concurrent thoughts, feelings, and behaviours. Each of these emotional aspects are self-managed either through avoidance, or by delayed disclosure and are frequently associated with poor health outcomes. There is a requirement for the healthcare team to be sensitised to these issues and to develop styles of communication that are empathic, reflective and non judgemental. A brief outline of evidence-based psychotherapy treatments is given.

Keywords: Psychological factors, Glycaemic control, Anxiety, Depression, Eating disorder, Diabetes distress, Maladaptive coping, Psychotherapy

Core tip: Psychological factors adversely influence efforts to optimise glycemic control. The focus on psychiatric diagnosis has done a disservice to people with diabetes who experience significant levels of sub-clinical distress and it is essential to develop an understanding of the psychological issues that underpin poor self-management of type 1 diabetes. The diabetes healthcare team needs to be sensitive to the underlying issues and to be confident in the use of consultation styles that facilitate recognition and appropriate signposting for specialised support and treatment.

INTRODUCTION

It has long been accepted that psychological factors adversely influence efforts to optimise glycemic control and for many years these have been addressed in the context of psychiatric diagnoses anxiety[1], depression[2,3] and eating disorders[4,5]. Until recently the Quality Outcomes Framework[6] has been used to remunerate United Kingdom General Practitioners for recording assessments of anxiety and depression in those living with long-term conditions. This focus on diagnosis has been to the detriment of people with diabetes who experience significant levels of distress, visible in terms of poor control but unrecognised in terms of clinical assessment and therefore under reported. More recently attention has been given to the need to differentiate between clinical diagnoses and diabetes-emotional distress[7-9]. This article, informed by literature and the clinical experience of the author, presents an introduction to psychological issues that interact with psychiatric co-morbidities and diabetes-specific distress, and a case scenario illustrating the interconnectedness of presenting problems and themes. A brief outline of psychotherapeutic models available to treat these difficulties is given.

Management of type 1 diabetes requires optimising a sequence of actions or behaviours that include blood glucose monitoring, carbohydrate counting, insulin administration and physical activity, in the context of cognitions and emotions (thoughts and feelings). On the face of it the most straightforward approach to management is to advise people what to do, and expect it will be done. Living with and managing diabetes in the context of education, employment, recreation, ill health and relationships to name a few aspects of daily living, can be challenging. Diabetes is not an exact science and day to day life, early learning, emotions and motivation can, and do emerge as barriers to the consistent application of the “straightforward” approach.

EMOTIONS AND COGNITIONS ASSOCIATED WITH DIABETES

Diabetes is the ultimate gatecrasher. There is no satisfactory explanation to answer the question “why me?” and at best glycaemic control can be managed, but unlike the party gatecrasher, diabetes cannot be sent away. Clinicians are familiar with the lexicon offered by people living with diabetes in response to the question “How does diabetes make you feel?” that includes words like anxious, worried, afraid, mood swings, depressed, euphoric, shame, guilty, angry and frustrated. Similarly when asked about thoughts triggered by living with diabetes the responses reflect what it means to live with the condition and its impact on quality of life, and the difficulties of management. This thinking interacts with beliefs about the self, the reaction of others and unconscious motives derived from early experience.

TOWARDS AN UNDERSTANDING OF THE MISMANAGEMENT OF DIABETES

In the way that we cannot separate carbohydrate counting, blood glucose monitoring and insulin dose adjustment in the understanding of a presenting problem such as poor control, so we cannot separate the co-existing thoughts, feelings, and behaviours.

Psychiatric diagnoses of anxiety, depression and eating disorders are frequently listed as psychological aspects of diabetes, and improvements in glycaemic control (HbA1c) reported as the primary outcome measure of treatment. As stated in the introduction, in recent years there has been increasing attention given to the need to differentiate psychiatric comorbidities and diabetes-related emotional distress. Identifying the factors that influence the decisions for particular actions that contribute to poor control is the crux of psychological formulation. Assessment of the presenting problem and the context in which it occurs offers a pathway to a personalised understanding that informs the treatment of choice. This might include further diabetes education, pharmacological treatment, appropriate psychological therapy, or indeed any combination of these.

Assessment of an individual presenting with poor control may reveal distress associated with, for example, a fear of hypoglycaemia. Thoughts might reflect a fear of loss of control, or of drawing unsolicited attention giving rise to emotions such as anxiety, frustration or guilt. Actions to elevate blood glucose such as reducing insulin or eating to maintain a “safe” blood glucose level result in both a reduction of risk of hypoglycaemia and a reduction in anxiety. Alternatively, high blood glucose readings frequently trigger guilt and fears about long term health. Evidence of high blood glucose is denied by avoidance of blood monitoring, and the emotional equilibrium thereby maintained. These are examples of the mismanagement of diabetes being used to manage emotional distress.

Managing diabetes requires multifactorial consideration of food choice and quantity, activity, blood glucose, ill health, ambient temperature, alcohol consumption, and menstrual cycle to name a few of the factors. The psychological responses are equally complex and influence actions with consequences on a continuum ranging from subtle to extreme outcomes on glycaemic control and psychological well-being.

PRESENTING PROBLEM AND UNDERLYING PSYCHOLOGICAL ISSUES

The following case history is used to illustrate psychological issues underlying poor control evidenced by elevated HbA1c and frequent episodes of hypoglycaemia. It invites consideration as to whether the presenting problem requires direct treatment or is a symptom of underlying difficulties that need to be addressed.

CASE STUDY (REPORTED WITH PERMISSION)

Sam is a 60-year old post menopausal woman approaching retirement. She has been married for 38 years and although she experienced difficulty with conception she has one adult child. Her family of origin practised strict religious beliefs and she was brought up to be sensitive to the needs of others before her own. She had little preparation for independent living and intimate relationships: indeed such topics were taboo and usually associated with duty, guilt, shame and blame. There was an expectation that she would be self-sufficient and undemanding which contributed to considerable reluctance to seek help and resulted in her needs not being met. She suffered a sexual assault in her late teens not disclosed at the time, for which she did not receive emotional support and which subsequently influenced intimate relationships and generated a sense of shame. Her predominant employment has involved looking after others in a variety of roles, consistently prioritising the needs of others above her own. Sam has had type 1 diabetes for 20 years with significant fluctuations in control over that time and frequent hypoglycaemia, severe episodes occurring most frequently during sleep. Weight and body-image concerns are relevant in terms of her self-perception as unloveable and unattractive. She engages in regular exercise and has the not uncommon challenge of balancing energy needs, insulin dose and extremes of blood glucose levels. Whilst there is no indication that Sam uses insulin omission to influence her weight she tends to maintain elevated blood glucose to protect against hypoglycaemia. Pervading themes reflect guilt, shame, blame, a sense of being undeserving and either not good enough or a failure.

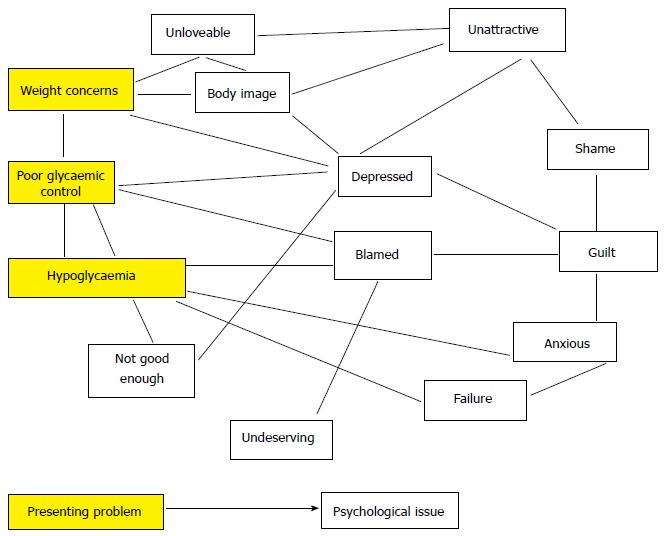

On the face of it a diabetes-specific intervention might focus on insulin adjustment, reducing episodes of hypoglycaemia, optimising exercise and blood glucose control or, less likely, weight management. The brief history offers insight into interconnecting psychological factors that contribute to poor glycemic control (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

The spider’s web: Visual representation of interconnecting psychological issues associated with the presenting problems of a female with type 1 diabetes.

We can map the interlinking of the psychological factors, many of which are derived from early experience, others of which are accentuated by the role of diabetes and its impact on daily living. The experience of hypoglycaemia potentially predisposes fear of further episodes interconnecting with blame from others for “getting it wrong”, shame and personal failure for “getting it wrong” and embarrassment and a fear of being out of control. Maladaptive coping behaviours include overeating and/or the reduction of insulin to elevate blood glucose, avoiding any physical exertion that may result in hypoglycaemia and avoiding social situations. The awareness that the coping mechanism results in short term relief with adverse consequences on long-term health perpetuates the cycle with resulting feelings of guilt, shame, and body-image concerns.

The spider’s web gives some indication of why managing diabetes can be so challenging. Advice to adjust insulin:carbohydrate ratios, conservative treatment of hypoglycaemia, dietary advice and information about women’s sexual function and diabetes may all be appropriate but do not address the psychological themes underpinning the maladaptive behaviours contributing to poor control.

PSYCHOLOGICAL ISSUES AND MALADAPTIVE COPING

The earlier paragraphs describe circumstances and events with psychological consequences, in the context of diabetes, that lead to maladaptive coping and mismanagement of diabetes. The following is a brief account of some of these with reference to the literature for more detailed exploration. Evidence has been provided for different components of type 1 diabetes distress: emotional burden, interpersonal and social distress, regimen related, and health care related[9-12]. The psychological issues are inextricably interconnected and related to specific aspects of diabetes-distress and presenting problems such as hypoglycaemia, fear of complications and body-image concerns.

Fear and anxiety

Fear and anxiety are the cognitive and emotional responses to threat. In order to reduce emotional discomfort individuals either “overdo” in an attempt to prevent the feared event or “under do” (avoid) the action in the misapprehension that by not addressing it, it will go away. The lack of exposure to the feared event (e.g., hypoglycaemia) means that the individual reinforces the avoidance behaviour and does not learn how to cope were the threat to occur.

Blame and shame

Blame and shame indicate perceived negative judgement. Both emotions result from and give rise to the instigation of thoughts of not being good enough, having done wrong, or having failed, and are consistent with the experience of distress. “Shame plays a major role in the eventual consequences of diabetes self-management”[13]. Embarrassment and shame are also associated with specific diabetes symptoms which are both embarrassing to experience and for which to seek help[14].

Stigma

“Health related stigma is a negative social judgement based on a feature of a condition or its management that may lead to perceived or experienced exclusion, rejection, blame, stereotyping and/or status loss”[15]. Consequences of stigma span emotional, behavioural and social domains with specific implications of an unwillingness to disclose the condition which may compromise care, and fear of being judged or blamed for suboptimal diabetes management. A model is proposed to understand diabetes-related stigma[15].

Guilt

Guilt is a personal emotion experienced when there is recognition that something has not been done as believed it should have been, or something has been done that should not have been. It is similar to shame in its negative impact on self esteem but tends to relate to a specific action whereas shame is more to do with the perception of self. It evokes efforts to correct or make reparation, however this can result in perpetuating the negative feelings as a consequence of negative thoughts about self worth.

Each of these emotional aspects are self managed either through avoidance, striving to maintain invisibility, with poor outcomes or by delayed disclosure which can intensify the distress, at least in the short term, and frequently are also associated with poor outcomes.

There is a requirement for the healthcare team to be sensitised to these issues and to develop styles of communication that are empathic, reflective and non judgemental.

Models of therapy

Assessment and formulation guide treatment plans and until there is a robust evidence base specific to people with diabetes that suggests otherwise there is a choice of psychological therapies available for accredited practitioners to use. Behaviour therapy[16] focuses on modification of observable behaviours without taking into account “invisible” emotions and cognitions and is rarely an appropriate model to use with people with type 1 diabetes.

Cognitive behavioural therapy

Traditional cognitive behavioural therapy is a goal oriented, problem focussed therapy that combines behavioural and cognitive models. It is a collaborative approach that focuses on current problems rather than past issues. It has evolved as a specific treatment for symptoms associated with specific diagnoses, and is used to challenge cognitive distortions thereby promoting behaviour change[17].

Acceptance and commitment therapy

Acceptance and Commitment Therapy is an example of “Third Wave Therapies”. It is particularly relevant in the context of fluctuating and frequently negative thoughts and feelings associated with diabetes. Rather than focus on the influence of emotions and cognitions as drivers for behaviour, the emphasis is on promoting value driven behaviour. The treatment facilitates a willingness to step back, notice and accept thoughts as they occur without becoming ensnared by the emotional response. Individuals commit to value driven actions whilst noticing the thoughts and feelings that invite self-sabotaging behaviour. For a detailed review of the full range of Third Wave therapies the reader is invited to a recent review article by Kahl et al[18].

Cognitive analytic therapy

Cognitive analytic therapy is a time limited therapy which integrates concepts from cognitive and psychodynamic models[19]. The treatment involves the identification of sequences of thoughts and emotions that explain how a problem is established and maintained. The recognition of unhelpful self-sabotaging patterns of interaction derived from early experience, replayed in later life are interpreted in the context of diabetes management.

CONCLUSION

Non-psychiatric psychological aspects of living with type 1 diabetes interconnect with the day to day self-management tasks and related diabetes distress. There is a need for the diabetes healthcare team to be sensitive to the underlying issues and to be confident in the use of consultation styles that facilitate recognition, assessment, and appropriate signposting for specialised support and treatment. There is an unequivocal need for the multi-disciplinary team to include experienced psychological-therapists with considerable knowledge of diabetes management so that difficulties can be addressed as an integral part of the diabetes care available.

Footnotes

Conflict-of-interest: None declared.

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article which was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/

Peer-review started: December 2, 2014

First decision: January 20, 2015

Article in press: February 12, 2015

P- Reviewer: Markopoulos AK, Martin-Villa JM S- Editor: Ji FF L- Editor: A E- Editor: Wu HL

References

- 1.Anderson RJ, Grigsby AB, Freedland KE, de Groot M, McGill JB, Clouse RE, Lustman PJ. Anxiety and poor glycemic control: a meta-analytic review of the literature. Int J Psychiatry Med. 2002;32:235–247. doi: 10.2190/KLGD-4H8D-4RYL-TWQ8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lustman PJ, Anderson RJ, Freedland KE, de Groot M, Carney RM, Clouse RE. Depression and poor glycemic control: a meta-analytic review of the literature. Diabetes Care. 2000;23:934–942. doi: 10.2337/diacare.23.7.934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gonzalez JS, Peyrot M, McCarl LA, Collins EM, Serpa L, Mimiaga MJ, Safren SA. Depression and diabetes treatment nonadherence: a meta-analysis. Diabetes Care. 2008;31:2398–2403. doi: 10.2337/dc08-1341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Peveler R, Eating disorders and insulin-dependent diabetes. Eur Eat Disorders Rev. 2000;8:164–169. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Larrañaga A, Docet MF, García-Mayor RV. Disordered eating behaviors in type 1 diabetic patients. World J Diabetes. 2011;2:189–195. doi: 10.4239/wjd.v2.i11.189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.QOF Guidance. 7th revision. Available from: http://bma.org.uk/qofguidance.

- 7.Fisher L, Skaff MM, Mullan JT, Arean P, Mohr D, Masharani U, Glasgow R, Laurencin G. Clinical depression versus distress among patients with type 2 diabetes: not just a question of semantics. Diabetes Care. 2007;30:542–548. doi: 10.2337/dc06-1614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.van Bastelaar KM, Pouwer F, Geelhoed-Duijvestijn PH, Tack CJ, Bazelmans E, Beekman AT, Heine RJ, Snoek FJ. Diabetes-specific emotional distress mediates the association between depressive symptoms and glycaemic control in type 1 and type 2 diabetes. Diabet Med. 2010;27:798–803. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-5491.2010.03025.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pallayova M, Taheri S. Targeting Diabetes Distress: The missing piece of the successful type 1 Diabetes Management Puzzle. Diabetes Spectrum. 2014;27:143–149. doi: 10.2337/diaspect.27.2.143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Polonsky WH, Anderson BJ, Lohrer PA, Welch G, Jacobson AM, Aponte JE, Schwartz CE. Assessment of diabetes-related distress. Diabetes Care. 1995;18:754–760. doi: 10.2337/diacare.18.6.754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Snoek FJ, Pouwer F, Welch GW, Polonsky WH. Diabetes-related emotional distress in Dutch and U.S. diabetic patients: cross-cultural validity of the problem areas in diabetes scale. Diabetes Care. 2000;23:1305–1309. doi: 10.2337/diacare.23.9.1305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Polonsky WH, Fisher L, Earles J, Dudl RJ, Lees J, Mullan J, Jackson RA. Assessing psychosocial distress in diabetes: development of the diabetes distress scale. Diabetes Care. 2005;28:626–631. doi: 10.2337/diacare.28.3.626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Archer A. Shame and diabetes self-management. Practical Diabetes International. 2014;31:1–5. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hillson R. Embarrassing diabetes. Practical Diabetes International. 2014;31:313–314. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Browne J, Ventura A, Mosely K, Speight J. “I’m not a druggie, I’m just a diabetic”: a qualitative study from the perspective of adults with type 1 diabetes. BMJ Open. 2014;4:e005625. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2014-005625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wolpe J. The Practice of Behaviour Therapy. 3rd ed. Pergamon General Psychology Series. New York: Pergamon Press; 1982. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cognitive Behavior Therapy: Basics and Beyond (2nd Revised edition), Judith Beck. 2th ed. New York: Guilford Publications New York; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kahl KG, Winter L, Schweiger U. The third wave of cognitive behavioural therapies: what is new and what is effective? Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2012;25:522–528. doi: 10.1097/YCO.0b013e328358e531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Introducing Cognitive Analytic Therapy: Principles and Practice. Ryle A, Kerr I. Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell Oxford; 2002. [Google Scholar]