Abstract

Twenty-seven grapevine (Vitis vinifera L.) varieties within 12 putative berry colour variation groups (conculta) were genotyped with 14 highly polymorphic microsatellite (simple sequence repeats (SSR)) markers. Three additional oligonucleotide primers were applied for the detection of the Gret1 retroelement insertion in the promoter region of VvMybA1 transcription factor gene regulating the UFGT (UDP-glucose: flavonoid 3-O-glucosyltransferase) activity. UFGT is the key enzyme of the anthocyanin biosynthetic pathway. SSR results proved that the analysed cultivars can be grouped only into nine concultas, the other three putative berry colour variant groups consist of homonyms as a consequence of misnaming. In the case of Sárfehér-Sárpiros, Delaware red-Delaware white and Járdovány fekete-Járdovány fehér, it was attested that they are not bud sports, but homonyms. Some conculta members could be differentiated according to the presence or the absence of the Gret1 retroelement (Chasselas, Furmint and Lisztes), while others, Bajor, Bakator, Gohér and Traminer conculta members, remained indistinguishable either by the microsatellites or the Gret1-based method.

Keywords: conculta, SSR, VvMybA1, Gret1 retroelement

Introduction

Mutations affected important traits of horticultural plants to a great extent during domestication of these species including fruit colour variations.[1] Zhukovsky [2] introduced the term of conculta for the colour mutant varieties. The Hungarian ampelographer Márton Németh [3] also adopted and extended this over-cultivar taxonomic category for grapevine. According to his theory, the grapevine conculta members originate from blue-berried ancestors as a consequence of bud mutation. The difference between the members can be recognized only by the colour of the berry, the autumn leaf colouration and the prostrate hairs of the shoot tips. Based on morphological traits Németh [4] differentiated 26 concultas, grown in Hungary.

The identification of the cultivars is very important at all phenological stages.[5] Besides ampelographic descriptors DNA fingerprints are significant tools in varietal characterization in grapevine. Among these molecular methods microsatellite (SSR = simple sequence repeats) analyses became widely used due to their reliability and high reproducibility.[6–8] Although the SSR markers made it possible to detect even clonal variations,[9–11] they are not applicable in all cases of somaclonal variations like bud mutations.[12] Bowers et al. [6] and Regner et al. [12] concluded that the SSR markers are not suitable for the discrimination of the members of Pinot group (Pinot blanc, Pinot gris, Pinot noir). Other molecular methods like Restriction Fragment Length Polymorphism (RFLP) and Random Amlified Polymorphic DNA (RAPD) also proved to be ineffective for differentiating berry colour variants.[13–16] Halász et al. [14] analysing autochthonous varieties in the Carpathian Basin with six polymorphic SSR markers could not discriminate the members of the Bajor, Bakator, Gohér and Lisztes concultas. Additionally they concluded that because of the high allelic differences the cultivar Bakator kék cannot be the member of the Bakator group. The name Bakator is a homonym confirming that the similarity in names does not certainly mean a bud mutation event. Existence of homonyms and synonyms is very frequent in the nomenclature.[8,17]

Slinkard and Singleton [18] suggested that the white berried cultivars originate from the coloured ones by loss-of-function mutations. The berry colour is determined by anthocyanin accumulation in the skin, which varies greatly in concentration and composition depending on the grape cultivar.[19] The key enzyme of anthocyanin biosynthesis is the UDP-glucose-flavonoid 3-O-glucosyl-transferase (UFGT). This enzyme does not express in the white berried cultivars, in spite of the fact that there are no differences in both VvUFGT promoter and coding region between white and coloured cultivars.[19,20] The anthocyanin biosynthesis is controlled by a transcription complex including the Myb genes, which activates the UFGT gene.[21]

The ancient wild grape had coloured berries and the nowadays-cultivated varieties derived from the ancient form. The white cultivars arose mostly from red-berried parents by different mutations in two adjacent Myb genes, VvMybA1 and VvMybA2.[22,23] Among these mutations, insertion of a retroelement, the Gret1 retrotransposon into the promoter region of the VvMybA1 gene leading to transcriptional inactivation of VvMybA1 was first identified in cultivars Italia and Muscat of Alexandria.[22] This mutant allele was named VvMybA1a, while the functional allele of the coloured cultivars is VvMybA1c. White berried cultivars are homozygous for Gret1 insertion, whereas the colour-skinned varieties contain at least one functional allele. In several white cultivars deletion of Gret1 from promoter region was observed resulting in a functional allele, VvMybA1b, containing only a short part, the 3′-LTR region of the retrotransposon, thus these types of red cultivars derived from their white-skinned progenitor.[22,23] Single nucleotide polymorphism in VvMybA2 coding region also could result in white berries.[11] Based on the results of Mitani et al. [24] wild Vitis species do not carry the VvMybA1 locus even if they are white berried.

Yakushiji et al. [25] showed that the deletional mutation of functional VvMybA1c from Pinot noir resulted in Pinot blanc. At the same time the other members of the Pinot conculta, Pinot gris and Pinot noir are undistinguishable with the retroelement based method.[26]

Kobayashi et al. [20] and Giannetto et al. [26] concluded that the colour mutations can be bidirectional: black-to-white and white-to-red/pink between the conculta members. These facts confirmed the result of Walker et al. [23] identifying two pale coloured mutations of the Cabernet sauvignon (Malian and Shalistin) as a deletion consequence in two regulatory genes of the berry colour locus.

In this paper we combine the knowledge of the cultivar characterization with SSR markers and the application of the Gret1 retroelement for discriminating 16 local Hungarian and 11 international putative or already proven bud sports.

Materials and methods

Plant material

The cultivars investigated in this study are listed in Table 2. Young leaves of the grapevine varieties were collected from grapevine collections maintained at Károly Róbert College in Eger, Szőlőskert Ltd. in Nagyréde, Helvécia and University of Pécs, Institute of Viticulture and Enology.

Table 2.

The analysed cultivars with the site of collection, geographical origin according to Németh,[4] berry colour, the possibility of discrimination by SSR method or by the Gret1 insertion into the VvMybA1 locus.

| Possibility of discrimination with |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Accession name | Collection site | Geographical origin | Berry colour | SSR | VvMybA1 |

| Bajor feketefájú | Pécs | convar. pontica | Black | No | no |

| Bajor kék | Pécs | convar. pontica | Black | No | yes |

| Bajor szürke | Pécs | convar. pontica | Grey | No | no |

| Bakator piros | Pécs | convar. pontica | Red | No | No |

| Bakator tüdőszínű | Pécs | convar. pontica | Pink | No | No |

| Chasselas blanc | Nagyréde | convar. orientalis | White | No | Yes |

| Chasselas rouge | Nagyréde | convar. orientalis | Red | No | Yes |

| Delaware red | Eger | hybrid | Red | Yes | Yes |

| Delaware white | Eger | hybrid | White | Yes | Yes |

| Furmint fehér | Pécs | convar. pontica | White | No | Yes |

| Furmint piros | Pécs | convar. pontica | Red | No | Yes |

| Gohér fehér | Pécs | convar. pontica | White | No | No |

| Gohér piros | Pécs | convar. pontica | Red | No | No |

| Gohér változó | Pécs | convar. pontica | White | No | No |

| Járdovány fehér | Helvécia | convar. pontica | White | Yes | Yes |

| Járdovány fekete | Helvécia | convar. pontica | Black | Yes | Yes |

| Lisztes fehér | Pécs | convar. pontica | White | No | Yes |

| Lisztes piros | Pécs | convar. pontica | Red | No | Yes |

| Merlot | Pécs | convar. occidentalis | Black | No | No |

| Merlot gris | Pécs | convar. Occidentalis | Grey | No | No |

| Pinot blanc | Nagyréde | convar. occidentalis | White | No | Yes |

| Pinot gris | Nagyréde | convar. occidentalis | Grey | No | No |

| Pinot noir | Nagyréde | convar. occidentalis | Black | No | No |

| Sárfehér | Helvécia | convar. pontica | White | Yes | Yes |

| Sárpiros | Helvécia | convar. pontica | Red | Yes | Yes |

| Traminer | Eger | convar. occidentalis | White | No | No |

| Traminer red | Eger | convar. occidentalis | Red | No | No |

Note: The Hungarian names indicate the berry colour of the cultivars: fehér = white; piros = red; változó = altering; szürke = grey; fekete = black, tüdőszínű = pink.

Short characterization of the putative concultas

Bajor is probably a Hungarian variety. It used to be cultivated in most wine regions of Hungary; presently it has no importance in the Hungarian viticulture – it can be found only in old plantations of quality wine regions (Tokaj Hegyalja, Mecsek).[4,27]

Bakator is a Carpathian Basin variety. Kék bakator, Piros, Tüdőszínű and Fehér Bakator carry the Bakator name; however, it was shown by SSR analysis that Kék bakator is a different cultivar and not a berry colour variant of Bakators.[14] Nowadays only Bakator piros is cultivated in Hungary on a few hectares.[27]

Chasselas: in spite of its French name it derives from Asia, its way to Europe is unknown. The most widely cultivated table grape in Hungary, Chasselas rouge, rose and b1ancs are the members of the conculta.[4,27]

Delaware red is of North-American origin, assumably a natural hybrid of Vitis vinifera, Vitis labrusca and Vitis aestivalis. In Hungary it can be found only in old vine yards, however earlier it was a popular cultivar in the Trans-Danubian part of Hungary. Delaware white was supposed to be the progeny of Delaware red as a result of open pollination.[27]

Furmint: old Hungarian wine grape with three variants: piros, fehér, változó. Fehér Furmint is the third most widespread cultivar in Hungary, particularly in the Tokaj Hegyalja region, one of the components of the world famous Tokay aszu. Piros and változó Furmints are maintained in gene banks.[27,28]

Gohér: old Hungarian variety, used as table and wine grape in the past, it has three variants (fehér, piros, változó). Recently Gohér fehér has been planted at the famous Tokaj wine region. Gohér piros and változó are conserved in gene banks.[27,28]

Járdovány: its origin is unknown. It was widespread in the past, but nowadays it can be found mainly in old plantations. Járdovány fehér wine is not a characteristic one, but Járdovány fekete has better quality, therefore it has got permission to be planted as wine grape in some regions of Hungary.[27]

Lisztes: old autochthonous variety of the Carpathian Basin, high yield and low wine quality are characteristic of Lisztes; it has no role in the present Hungarian viticulture.[4]

Merlot: known since the eighteenth century, derives from France (Bordeaux). It is cultivated all over the world; it was registered in Hungary in 1973.[27,28]

Pinot derives from France, where it has been growing for centuries. It is a worldwide cultivated variety with the following berry colour variants: Pinot gris, noir, blanc, rose and violet.[27]

Sárfehér is an old white berried Hungarian cultivar. Because of the first syllable of its name (Sár = mud) it can be assumed that the red berried Sárpiros is also a berry colour variant. Before the Phylloxera epidemic it was the characteristic variety of Somló and Neszmély in Hungary.[27,28]

Traminer: its origin is uncertain. Generally it was thought to derive from Tramin (village in South Tirol). Red, blue and white berry colour variants of Traminer are known, but only the red grape is cultivated in Hungary, the other two exist only in collections.[27]

DNA extraction and Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR) analysis

DNA was extracted with Qiagen DNeasy Plant Mini Kit according to the manufacturer's protocol (Qiagen-Biomarker Ltd., Gödöllő, Hungary). The quality and quantity of the isolated DNA was checked on 1.5% agarose gel with electrophoresis and by NanoDrop spectrophotometer (BioScience Ltd. Budapest).

Fourteen fluorescent-labelled (FAM-6 and Cy5) microsatellite primer pairs: Scu10, VVS2,[29] VVMD5, VVMD7,[30] VVMD21, VVMD25, VVMD27, VVMD28, VVMD31, VVMD36,[31] VrZag62, VrZag79, VrZag83 and VrZag112 [32] were used in the analyses. The PCR conditions are described by Regner et al. [12] and Halász et al.[14]

For the detection of the Gret1 retroelement in the promoter region of the VvmybA1 three oligonucleotide primers were used as reported by Kobayashi et al.,[33] with the modification of This et al.[34] The PCRs were carried out in an iCycler (BioRad) equipment. The PCR program for the amplification of Gret1 was as follows: initial denaturation at 94 °C for 3 min, 35 cycles of 94 °C for 30 sec/55 °C for 30 sec/72 °C for 90 sec, with a final step at 72 °C for 10 min. PCR products were checked after 1.2% agarose gel electrophoresis. SSR loci were analysed on ABI 310 genetic analyzer (Biomi Ltd., Gödöllő, Hungary) and ALF-Express DNA Fragment Analyzer (Amersham Biosciences, AP Hungary Ltd., Budapest, Hungary).

The standardization of the allele sizes was made by using French and Hungarian reference varieties such as Pinot noir, Chardonnay and Irsai Olivér, Csaba gyöngye, and Pozsonyi, respectively. Among these cultivars some parent-progeny relationships exist confirmed by SSR results.[31,35]

Results and discussion

SSR analysis

The SSR profiles of the characterized 27 samples are presented in Table 1. The SSR analysis resulted in 15 different allele profiles including nine concultas. Individual varietal differences could be observed in the case of the following cultivars: Delaware white-Delaware red, Sárfehér-Sárpiros and Járdovány fehér-Járdovány fekete meaning that they do not constitute concultas, it can be supposed that these cultivars have only homonym names and they are not the results of bud mutations. Homonymy and synonymy is a common phenomenon in grapevine nomenclature, which can be clarified by microsatellite markers.[36–38]

Table 1.

SSR allele sizes of the 27 cultivars at 14 loci.

| Accession name | Berry colour | Scu10 | VVS2 | VVMD5 | VVMD7 | VVMD21 | VVMD25 | VVMD27 | VVMD28 | VVMD31 | VVMD36 | VrZAG62 | VrZAG79 | VrZAG83 | VrZAG112 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bajor feketefájú | Black | 202:208 | 134:154 | 228:238 | 243:243 | 248:256 | 242:244 | 182:196 | 238:250 | 209:209 | 254:254 | 192:200 | 252:262 | 193:193 | 243:243 |

| Bajor kék | Black | 202:208 | 134:154 | 228:238 | 243:243 | 248:256 | 242:244 | 182:196 | 238:250 | 209:209 | 254:254 | 192:200 | 252:262 | 193:193 | 243:243 |

| Bajor szürke | Grey | 202:208 | 134:154 | 228:238 | 243:243 | 248:256 | 242:244 | 182:196 | 238:250 | 209:209 | 254:254 | 192:200 | 252:262 | 193:193 | 243:243 |

| Bakator piros | Red | 202:208 | 134:134 | 228:242 | 243:257 | 242:256 | 244:244 | 180:186 | 236:250 | 201:209 | 266:288 | 192:198 | 254:254 | 191:197 | 237:241 |

| Bakator tüdőszínű | Pink | 202:208 | 134:134 | 228:242 | 243:257 | 242:256 | 244:244 | 180:186 | 236:250 | 201:209 | 266:288 | 192.198 | 254:254 | 191:197 | 237:241 |

| Chasselas blanc | White | 204:214 | 134:144 | 228:236 | 242.250 | 248:266 | 244:260 | 186:190 | 220:270 | 209:213 | 264:264 | 196:206 | 252:260 | 193:203 | 243:243 |

| Chasselas rouge | Red | 204:214 | 134:144 | 228:236 | 242.250 | 248:266 | 244:260 | 186:190 | 220:270 | 209:213 | 264:264 | 196:206 | 252:260 | 193:203 | 243:243 |

| Delaware fehér | White | 202:204 | 134:134 | 228:228 | 239:243 | 242:266 | 244:244 | 186:190 | 234:248 | 203:209 | 258:264 | 198:208 | 252:258 | 191:203 | 243:243 |

| Delaware piros | Red | 204:210 | 146:150 | 236:236 | 231:231 | 220:220 | 244:250 | 204:210 | 218:254 | 199:201 | 240:250 | 202:212 | 252:260 | 159:167 | 231:243 |

| Furmint fehér | White | 202:208 | 134:154 | 228:242 | 243:253 | 248:258 | 242:244 | 180:196 | 230:250 | 209:209 | 254:276 | 192:208 | 238:250 | 191:191 | 243:243 |

| Furmint piros | Red | 202:208 | 134:154 | 228:242 | 243:253 | 248:258 | 242:244 | 180:196 | 230:250 | 209:209 | 254:276 | 192:208 | 238:250 | 191:191 | 243:243 |

| Gohér fehér | White | 202:208 | 134:154 | 240:240 | 243:253 | 242:256 | 242:244 | 182:196 | 236:250 | 207:211 | 254:288 | 190:208 | 252:262 | 193:193 | 241:241 |

| Gohér piros | Red | 202:208 | 134:154 | 240:240 | 243:253 | 242:256 | 242:244 | 182:196 | 236:250 | 207:211 | 254:288 | 190:208 | 252.262 | 193:193 | 241:241 |

| Gohér változó | White | 202:208 | 134:154 | 240:240 | 243:253 | 242:256 | 242:244 | 182:196 | 236:250 | 207:211 | 254:288 | 190:208 | 252:262 | 193:193 | 241:241 |

| Járdovány fehér | White | 208:214 | 142:144 | 228:236 | 243:253 | 242:248 | 242:244 | 180:196 | 230:262 | 209:209 | 266:276 | 200:208 | 250:250 | 197:197 | 245:245 |

| Járdovány fekete | Black | 202:208 | 134:154 | 222:232 | 243:253 | 248:258 | 242:244 | 180:196 | 230:250 | 209:209 | 254:276 | 200:208 | 250:250 | 191:191 | 237:245 |

| Lisztes fehér | White | 208:208 | 134:144 | 228:234 | 251:251 | 248:256 | 242:244 | 182:182 | 236:250 | 207:211 | 276:288 | 208:208 | 238:260 | 193:197 | 241:241 |

| Lisztes piros | Red | 208:208 | 134:144 | 228:234 | 251:251 | 248:256 | 242:244 | 182:182 | 236:250 | 207:211 | 276:288 | 208:208 | 238:260 | 193:197 | 241:241 |

| Merlot | Black | 202:216 | 140:152 | 228:238 | 243:251 | 242:248 | 242:254 | 190:192 | 230:236 | 209:213 | 254:254 | 198:198 | 260:260 | 197:203 | 231:245 |

| Merlot gris | Grey | 202:216 | 140:152 | 228:238 | 243:251 | 242:248 | 242:254 | 190:192 | 230:236 | 209:213 | 254:254 | 198:198 | 260:260 | 197:203 | 231:245 |

| Pinot blanc | White | 204:216 | 138:152 | 230:240 | 243:247 | 248:248 | 242:252 | 186:190 | 220:236 | 213:213 | 254:254 | 192:198 | 242:248 | 191:203 | 243:243 |

| Pinot gris | Grey | 204:216 | 138:152 | 230:240 | 243:247 | 248:248 | 242:252 | 186:190 | 220:236 | 213:213 | 254:254 | 192:198 | 242:248 | 191:203 | 243:243 |

| Pinot noir | Black | 204:216 | 138:152 | 230:240 | 243:247 | 248:248 | 242:252 | 186:190 | 220:236 | 213:213 | 254:254 | 192:198 | 242:248 | 191:203 | 243:243 |

| Sárfehér | White | 202:208 | 134:152 | 226:238 | 251:259 | 242:248 | 244:258 | 182:196 | 250:280 | 207:207 | 264:264 | 208:208 | 250:250 | 191:193 | 245:245 |

| Sárpiros | Red | 202:208 | 134:134 | 226:240 | 251:257 | 242:242 | 242:258 | 180:196 | 270:280 | 207:209 | 264:288 | 190.208 | 250:258 | 193:193 | 237:245 |

| Traminer | White | 204:208 | 152:152 | 234:240 | 247:261 | 248:248 | 254:254 | 190:190 | 236:236 | 201:213 | 254:264 | 192:198 | 248:254 | 191:203 | 237:243 |

| Traminer red | Red | 204:208 | 152:152 | 234:240 | 247:261 | 248:248 | 254:254 | 190:190 | 236:236 | 201:213 | 254:264 | 192:198 | 248:254 | 191:203 | 237:243 |

At the same time based on 14 microsatellite loci there were no differences in allele sizes within the following concultas: Bajor, Bakator, Chasselas, Furmint, Gohér, Lisztes, Merlot, Pinot and Traminer (Table 1). Our results supported the earlier conclusions of Regner et al. [12] that there are no SSR allele differences between Pinot samples.

Two members of the Chasselas, Merlot and Traminer group were analysed in this work. Based on the SSR profiles, none of the putative conculta members differed from each other at the investigated loci.

According to Galet [39] and Csepregi and Zilai [28] Delaware white is the seedling of Delaware red (V. labrusca L. × V. aestivalis Michx.) but their SSR profile excludes the possibility of parent–progeny relationship. These cultivars are homonyms and not the results of either bud mutation or paternity.

In the case of the cultivars Sárfehér-Sárpiros and Járdovány fekete-Járdovány fehér the name identity can be explained also with homonymy since the genetic profile disclaims the possibility of colour mutation.

These results suggest the following conclusion: similar or identical names can originate from two main sources: (1) emergence of concultas as a consequence of bud mutation (Bajor, Bakator, Chasselas, Furmint, Gohér, Lisztes, Merlot, Pinot and Traminer) and (2) homonymy (Delaware red-Delaware white, Járdovány fekete-Járdovány fehér, Sárfehér-Sárpiros).

Molecular analyses of VvMybA1 locus

Since conculta members were indistinguishable by SSR markers our second aim was not only to differentiate them but also find the reason for the berry colour variation. The method that we applied is based on detecting the presence or absence of the Gret1 retrotransposon in the promoter region of the VvMybA1 transcription factor gene. In majority of the white berried cultivars transcription of the UFGT gene (coding the key enzyme in the anthocyanin biosynthetic pathway) is blocked, because of the insertion of Gret1 retrotransposon into VvMybA1 promoter.[25,34] This et al. [34] reported three white berried cultivars (Avgoulato, Gamay Castille mutation blanche and Sultanina-Gora Chirine) which did not contain the Gret1 in the VvMybA1 promoter.

Kobayashi et al. [22] described three alleles at VvMybA1 locus based on the presence (VvMybA1a) or absence of Gret1 (VvMybA1c) element in the promoter of the gene. The third one VvMybA1b contains a 3′-LTR sequence remaining after Gret1 deletion.

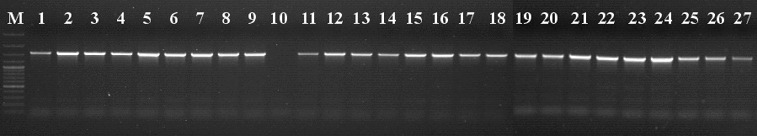

The results of PCR analysis of the promoter region of the VvMybA1 transcription factor gene in five proven Hungarian concultas (Bajor, Bakator, Furmint, Gohér and Lisztes) are shown in Figure 1. Amplification of an ∼1500 bp DNA fragment indicates the presence of VvMybA1a allele in each variety (Figure 1), independently of the actual berry colour except Bajor kék which does not contain the Gret1 insertion at all (it is homozygous for the VvMybA1c allele). Analysis of the functional VvMybA1 allele resulted in PCR products only in the coloured cultivars due to VvMybA1b and VvMybA1c alleles (Figure 2). The coloured members of these five Hungarian concultas, Bajor szürke, Bajor feketefájú, Bakator piros Bakator tüdőszínű, Furmint piros and Lisztes piros are heterozygous for the Gret1 retroelement, therefore the anthocyanin biosynthesis is undisturbed (Figure 2). Interestingly the red berried Gohér piros does not contain any functional VvMybA1 (b, c) alleles. Two members of Bajor conculta (Bajor szürke and feketefájú) gave identical DNA pattern at the VvMybA1 locus, showing that they contain both the functional VvMybA1c and the non-functional VvMybA1a alleles.

Figure 1.

Detection of VvMybA1a allele (containing Gret1 retrotransposon). M: DNA molecular weight marker (Fermentas GeneRuler 100 bp Ladder Plus / 3000 bp, 2000 bp, 1500 bp, 1200 bp, 1031 bp, 900 bp, 800 bp, 700 bp, 600 bp, 500 bp, 400 bp, 300 bp, 200 bp, 100 bp); Lane 1: Lisztes piros; Lane 2: Lisztes fehér; Lane 3: Bakator piros; Lane 4: Bakator tüdőszínű; Lane 5: Gohér piros; Lane 6: Gohér fehér; Lane 7: Gohér változó; Lane 8: Furmint piros; Lane 9: Furmint fehér; Lane 10: Bajor kék; Lane 11: Bajor feketefájú; Lane 12: Bajor szürke; Lane 13: Sárpiros; Lane 14: Sárfehér; Lane 15: Járdovány fekete; Lane 16: Járdovány fehér; Lane 17: Chasselas rouge; Lane 18: Chasselas blanc; Lane 19: Pinot noir; Lane 20: Pinot gris; Lane 21: Pinot blanc; Lane 22: Traminer red; Lane 23: Traminer; Lane 24: Merlot; Lane 25: Merlot gris; Lane 26: Delaware red; Lane 27: Delaware white.

Figure 2.

Detection of VvMybA1b and VvMybA1c alleles. M: DNA molecular weight marker (Fermentas GeneRuler 100 bp Ladder Plus / 3000 bp, 2000 bp, 1500 bp, 1200 bp, 1031 bp, 900 bp, 800 bp, 700 bp, 600 bp, 500 bp, 400 bp, 300 bp, 200 bp, 100 bp); Lane 1: Lisztes piros; Lane 2: Lisztes fehér; Lane 3: Bakator piros; Lane 4: Bakator tüdőszínű; Lane 5: Gohér piros; Lane 6: Gohér fehér; Lane 7: Gohér változó; Lane 8: Furmint piros; Lane 9: Furmint fehér; Lane 10: Bajor kék; Lane 11: Bajor feketefájú; Lane 12: Bajor szürke; Lane 13: Sárpiros; Lane 14: Sárfehér; Lane 15: Járdovány fekete; Lane 16: Járdovány fehér; Lane 17: Chasselas rouge; Lane 18: Chasselas blanc; Lane 19: Pinot noir; Lane 20: Pinot gris; Lane 21: Pinot blanc; Lane 22: Traminer red; Lane 23: Traminer; Lane 24: Merlot; Lane 25: Merlot gris; Lane 26: Delaware red; Lane 27: Delaware white.

Our results are in accordance with the earlier published works on the correlation between the presence of Gret1 and the loss of the berry colour.[26,34]

Although Sárfehér, Járdovány fekete and Delaware red have not proven to be concultas, we analysed their VvMybA1 locus. Red berried Sárpiros and Járdovány fekete are heterozygous for the Gret1 insertion.

Surprisingly, in the case of the characterization of the promoter region of the VvMybA1 transcription factor gene, the primers amplified a larger fragment in the same region in Delaware red (Figure 2).

In Traminer red – similar to Gohér piros – no functional VvMybA1b or c alleles could be detected. The members of the Bajor, Bakator and Gohér concultas were indistinguishable based on the Gret1 retroelement. Thus these data call for a further study in order to find an unambiguous method for distinguishing varieties in the concultas. Our results also revealed that Chasselas rouge – likewise Lisztes piros and Furmint piros – contains a VvMybA1b allele. The possibility of discrimination and identification of the investigated cultivars are listed in Table 2.

Conclusions

The results of the present study demonstrate that the applied 14 SSR markers were appropriate to prove which cultivars constitute concultas. Nine of the 12 putative cultivar groups can be considered as real concultas. Members of these concultas were indistinguishable with the SSR primer set used in this study. Earlier results proved the loss of berry colouration to be the consequence of Gret1 insertion in the VvMybA1 promoter region. Therefore we analysed the VvMybA1 locus coding a key transcriptional factor of berry anthocyanin biosynthesis. Testing three alleles of VvMybA1 (a, b, c) among the five Hungarian concultas only Furmint piros and Lisztes piros could be differentiated from the white berried variants. Bajor (except Bajor kék), Bakator and Gohér concultas require further investigations to clarify the genetic background of their berry colour.

Funding Statement

This work was supported by COST Action [FA 1003], Ministry of Human Resources [Research Centre of Excellence-17586-4/2013/TUDPOL] and MAG Hungarian Economic Development Centre [KTIA_AIK_12-1-2012-0012].

References

- Holton TA, Cornish EC. Plant Cell. 1995;7:1071–1083. doi: 10.1105/tpc.7.7.1071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhukovsky PM. Kulturnije rasztyenyija i ih szorodicsi [Cultivated plants and their wild relatives] Moszkva: Akad. Izd.; 1950. [Google Scholar]

- Nemeth M. Borszől. őfajták határozókulcsa. Budapest: Mezőgazdasági Press; 1966. [Google Scholar]

- Németh M. Ampelográfiai album. Budapest: Mezőgazdasági Press; 1967. Termesztett borszőlőfajták 1 [Ampelographic album. Cultivars of wine grapes 1] [Google Scholar]

- Karatas H, Degirmenci D, Velasco R, Vezzulli S. Ağaoğlu YS. Sci Hortic. 2007;114:164–169. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.scienta.2007.07.001 [Google Scholar]

- Bowers JE, Bandman EB, Meredith CP. Am J Enol Vitic. 1993;44:266–274. [Google Scholar]

- Sefc KM, Guggenberger S, Regner F, Lexer C. Vitis. 1998;37:123–125. Glossl J, Steinkellner H. [Google Scholar]

- Ulanowsky S, Gogorcena Y, Martinez De Toda F, Ortiz JM. Sci Hortic. 2002;92:241–254. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0304-4238(01)00291-6 Available from. [Google Scholar]

- Imazio S, Labra M, Grassi F, Winfield M. Plant Breed. 2002;121:531–535. http://dx.doi.org/10.1046/j.1439-0523.2002.00762.x Bardini M, Scienza A. Available from. [Google Scholar]

- Regner F, Wiedeck E, Stadlbauer A. Vitis. 2000;39:103–107. [Google Scholar]

- Vignani R, Bowers JE, Meredith CP. Sci Hortic. 1996;65:163–169. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/0304-4238(95)00865-9 [Google Scholar]

- Regner F, Stadlbauer A, Eisenheld C, Kaserer H. Am J Enol Vitic. 2000;51:7–14. [Google Scholar]

- Bourquin JC, Sonko A, Otten L, Walter B. Theor Appl Genet. 1993;87:431–438. doi: 10.1007/BF00215088. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/BF00215088 Available from. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halasz G, Veres A, Kozma P, Kiss E. Vitis. 2005;44(4):173–180. Balogh A, Galli Z, Szõke A, Hoffmann S, Heszky L. [Google Scholar]

- Tschammer J, Zyprian E. Vitis. 1994;33:249–250. [Google Scholar]

- Ye GN, Soylemezoglu G, Weeden NF, Lamboy WF. Vitis. 1998;37(1):33–38. Pool RM, Reisch BI. [Google Scholar]

- Maletic E, Sefc KM, Steinkellner H, Kontic JK, Pejic I. Vitis. 1999;38(2):79–83. [Google Scholar]

- Slinkard KW, Singleton VL. Vitis. 1984;23:175–178. [Google Scholar]

- Boss PK, Davies C, Robinson SP. Plant Mol Biol. 1996;32:565–569. doi: 10.1007/BF00019111. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/BF00019111 Available from. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kobayashi S, Ishimaru M, Ding CK, Yakushiji H, Goto N. Plant Sci. 2001;160:543–550. doi: 10.1016/s0168-9452(00)00425-8. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0168-9452(00)00425-8 Available from. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kobayashi S, Ishimaru M, Hiroika K, Honda C. Planta. 2002;215:924–933. doi: 10.1007/s00425-002-0830-5. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s00425-002-0830-5 Available from. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kobayashi S, Goto-Yamamoto N, Hirochika H. Science. 2004;304:982. doi: 10.1126/science.1095011. http://dx.doi.org/10.1126/science.1095011 Available from. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker AR, Lee E, Bogs J, McDavid DAJ. Plant J. 2007;49:772–785. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2006.02997.x. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-313X.2006.02997.x Thomas MR, Robinson SP. Available from. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitani N, Azuma A, Fukai E, Hirochika H, Kobayashi S. Vitis. 2009;48(1):55–56. [Google Scholar]

- Yakushiji H, Kobayashi S, Goto-Yamamoto N, Jeong ST. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem. 2006;70:1506–1508. doi: 10.1271/bbb.50647. http://dx.doi.org/10.1271/bbb.50647 Sueta T, Mitani N, Azuma A. Available from. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giannetto S, Velasco R, Troggio M, Malacarne G. Plant Sci. 2008;175:402–409. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.plantsci.2008.05.010 Storchi P, Cancellier S, De Nardi B, Crespan M. Available from. [Google Scholar]

- Benyei F, Lorincz A. Borszőlőfajták, csemegeszőlő-fajták és alanyok. Budapest: Mezőgazda Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Csepregi P, Zilai J. Szőlőfajta ismeret és használat. Budapest: Mezőgazdasági Press; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas MR, Scott NS. Theor Appl Genet. 1993;86:985–990. doi: 10.1007/BF00211051. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/BF00211051 Available from. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowers JE, Dangl GS, Vignani R, Meredith CP. Genome. 1996;39:628–633. doi: 10.1139/g96-080. http://dx.doi.org/10.1139/g96-080 Available from. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowers JE, Dangl GS, Meredith CP. Am J Enol Vitic. 1999;50(3):243–246. [Google Scholar]

- Sefc KM, Regner F, Turetschek E, Glossl J, Steinkellner H. Genome. 1999;42:1–7. http://dx.doi.org/10.1139/g98-101 Available from. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kobayashi S, Yamamoto NG, Hirochika H. J Jpn Soc Hortic Sci. 2005;74:196–203. http://dx.doi.org/10.2503/jjshs.74.196 Available from. [Google Scholar]

- This P, Cadle-Davidson M, Lacombe T, Owens CL. Theor Appl Genet. 2007;114:723–730. doi: 10.1007/s00122-006-0472-2. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s00122-006-0472-2 Available from. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiss E, Kozma P, Halasz G, Veres A. St. Louis, MO: 2005. Proceedings of the International Grape Genomics Symposium; pp. 79–87. Galli Zs, Szõke A, Hoffmann S, Molnár S, Balogh A, Heszky L. [Google Scholar]

- Jahnke G, Korbuly J, Majer J, Gyorffyne Molnar J. Sci Hortic. 2007;114(1):71–73. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.Sscienta.2007.05.011 Available from. [Google Scholar]

- Martin JP, Santiago J, Pinto-Cardine O, Leal F. Genet Resour Crop Evol. 2006;53:1255–1261. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10722-005-5679-6 Martinez MC, Ortiz JM. Available from. [Google Scholar]

- Schneider A, Carra A, Akkak A, This P. Vitis. 2001;40:197–203. Laucou V, Botta R. [Google Scholar]

- Galet P. Cepages Et Vignobles De France [Grapes and vineyards of France: French ampelography] Montpellier: Imprimerie Paul Déhan; 1988. [Google Scholar]