Highlights

-

•

Brain metastasis from UPSC is rare, with 9 cases in the literature.

-

•

UPSC may resemble other endometrial cancers in regard to brain metastatic behavior.

-

•

When appropriate, it seems that multimodal therapy offers the best outcomes.

Keywords: Uterine papillary serous carcinoma, Brain metastasis

Introduction

While endometrial cancer is the most common gynecological cancer with a generally favorable prognosis, the histological subtype of serous carcinoma is more aggressive and fortunately uncommon. Uterine serous carcinoma (USC) accounts for about 10% of cases of endometrial cancer and yet 39% of its deaths (Boruta et al., 2009). Brain metastasis from endometrial cancer is also rare, with a rate of 0.6% from a review of over 10,000 patients (Piura and Piura, 2012). This recent review of 35 studies by Piura et al. identified 115 cases of endometrial cancer that metastasized to the brain, of which 4 were USC (Piura and Piura, 2012). A further review of the literature uncovered an additional 4 cases. Here we present a new case from our institution, review the existing literature, and discuss current treatment options.

Case report

The patient is a 55 year-old woman G1P1001 with no significant medical history who was diagnosed with stage IIIC2 USC in Cartagena, Spain. She initially presented with postmenopausal bleeding and pelvic fullness. A CT scan was consistent with an endometrial and left adnexal solid mass, retroperitoneal lymphadenopathy, mild ascites, grades I–II ureterohydronephrosis, and nonspecific pulmonary micronodules. Laboratory studies revealed an elevated CA-125 level of 121 units/mL. Subsequent MRI suggested that the mass invaded greater than 50% of the thickness of the myometrium. In July 2012, she underwent a total abdominal hysterectomy, bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy, pelvic and para-aortic lymph node dissection, omentectomy, and appendectomy, followed by six cycles of carboplatin/paclitaxel, pelvic radiation, and vaginal brachytherapy. She was monitored with serial CT images of the chest/abdomen/pelvis and CA-125 levels. Imaging in April 2013 was negative and CA-125 level was 26 units/mL in May 2013. She then immigrated to the US.

On June 2013, the patient presented to the emergency room with headache and dizziness of 3 days duration. She also reported an episode of urinary incontinence and near-syncope but denied any other focal neurological deficits. Her neurological exam was normal. A head CT scan revealed significant bifrontal edema with suggestion of an underlying lesion. An MRI demonstrated a well-circumscribed heterogeneously enhancing mass involving the anterior body of the corpus callosum and extending superiorly to the falx cerebri, measuring 3.6 × 4.1 cm (Fig. 1). Her CA-125 level was 107 units/mL. A CT of the chest, abdomen and pelvis was negative for metastatic disease.

Fig. 1.

Preoperative sagittal MRI with IV contrast showing enhancing mass involving the anterior body of the corpus callosum.

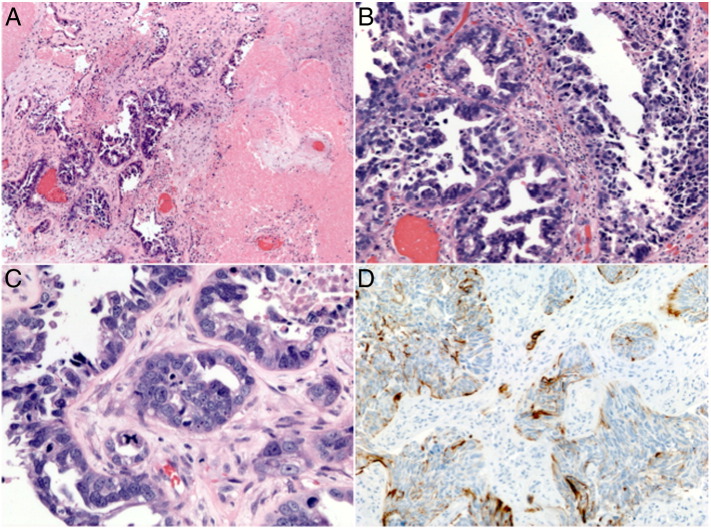

Later that month, she underwent a bifrontal craniotomy and tumor resection via right sided para-falcine approach. Histology revealed cerebral metastasis from serous carcinoma with immunohistochemistry profile (CK7 +, CK8/18 +, CK20 −, CDX2 −, BRST2 −, TTF1 −) consistent with primary endometrial carcinoma (Fig. 2). Postoperatively, she developed bilateral pulmonary emboli with a saddle embolism component.

Fig. 2.

(A) Microscopic low-power view showing brain parenchyma infiltrated by carcinoma and extensive areas of necrosis (H&E, × 40). (B) Medium-power view showing tumor forming glandular structures and a pseudopapillary arrangement of the tumor cells (H&E, × 200). (C) High-power view showing highly pleomorphic tumor cells and one atypical tetra-polar mitotic figure (blue arrow, H&E, × 400). (D) Tumor cells with positive cytokeratin-7 immunohistochemical stain (CK7, × 200).

The patient was subsequently evaluated for consolidative whole brain radiation (WBRT) vs. stereotactic radiosurgery (SRS) to the postoperative cavity and residual tumor. Due to the size of the postoperative bed, as well as rapid interval post-surgical growth, she was given WBRT followed by chemotherapy (gemcitabine and carboplatin). Residual tumor was left attached to the corpus callosum and pericallosal arteries, as it was thought that aggressive resection of this portion would carry a high risk of post-surgical neurologic morbidity; however about 20 days later, reimaging suggested a continued growth of the residual tumor posteriorly along the corpus callosum and superiorly into the frontal lobes. In February 2014, imaging revealed metastatic lung nodules. As of submission date, she is alive with disease on chemotherapy.

Discussion

USC is an uncommon form of endometrial cancer that rarely metastasizes to the brain. Herein we present a summary of the eight reported cases in the literature; our case report marks the ninth. An extraction of clinicopathological features (age, stage, grade, lymphovascular space involvement), time interval to brain metastasis, diagnostic findings (number and location of brain metastases, presence of systemic disease), treatment, and survival is summarized in Table 1 (Petru et al., 2001, Gulsen and Terzi, 2013, Chura et al., 2007, Gien et al., 2004, Talwar and Cohen, 2012, Dietrich et al., 2005, Comert et al., 2012).

Table 1.

Summary of nine case reports of brain metastasis from USC.

| Case 1 |

Case 2 |

Case 3 |

Case 4 |

Case 5 |

Case 6 |

Case 7 |

Case 8 |

Case 9 |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Petru 2001 | Gien 2003 | Gien 2003 | Dietrich 2005 | Chura 2007 | Comert 2012 | Talwar 2012 | Gulsen 2013 | Sinai 2013 | |

| Age at diagnosis of metastasis | 60 | 72 | 82 | 72 | 63 | Unknown | 68 | 71 | 55 |

| Stage | Unstaged | IIIC | IIB | IC | IA | IB | IA | Unknown | IIIC2 |

| Grade | 3 | Unknown | Unknown | Unknown | 3 | 3 | 3 | Unknown | 3 |

| LVSI | + | + | − | Unknown | Unknown | Unknown | − | Unknown | + |

| Depth of myometrial invasion | “Deep, serosal involvement” | > 50% | > 50% | > 50% | < 50% | > 50% | 0% | Unknown | > 50% |

| Interval (months) between primary diagnosis & brain metastasis | N/A* | 40 | 24 | 22 | 0.6 | 2 | > 60 | 27 | 11 |

| Number of brain metastases | Solitary | Multiple | Multiple | Unknown | Unknown | Solitary | Unknown | Multiple | Solitary |

| Systemic disease | None | Lung | Vault | Liver, lung | None | “Disseminated abdominal spread” | Lung | Unknown | None |

| Lesion location | R cerebellum | Cerebellum, L temporal | R frontal, R temporal, R parietal, bioccipital | Unknown | Unknown | Unknown | Unknown | Posterior fossa, R frontal lobe | Bifrontal tumor |

| Surgical excision | + | − | − | − | + | − | − | + | + |

| Brain metastasis treatment | Radiosurgery, chemotherapy, medroxyprogesterone | WBRT | Steroids | Unknown | WBRT, chemotherapy | Unknown | WBRT, chemotherapy | WBRT, chemotherapy | WBRT, chemotherapy |

| Brain metastasis survival (months) | 15 | 5 | 0.25 | 2 | 9.2 | 5 | > 3 | > 9 | Alive with disease, > 12 |

Among the nine cases of USC metastatic to the brain, the median age was 69.5 with a median survival of 5 months since diagnosis of brain metastasis. Our case report is the youngest patient at 55 and she is still alive at 12 months, currently undergoing treatment.

The stages of USC were varied, with 4 stage I, 3 stage III, 1 unstaged, and 1 unreported stage. This variation translated into a large interval of diagnosis of brain metastasis from USC, with a median interval of 23 months (range, 0.6 months to greater than 5 years). This is consistent with the previous finding of a median of 17 months (range, 2 to 108 months) for all endometrial carcinoma (Piura and Piura, 2012).

Most of the cancers were high-grade with > 50% myometrial invasion and signs of systemic disease at the time of brain metastasis (although 3 cases showed no other sites of metastases). This finding is also similar to Piura et al.'s conclusion that 80% of patients who developed brain metastases from endometrial carcinoma presented with high-grade disease and about half had disseminated disease, although certainly our case series yields far too few numbers to state any definitive conclusions (Piura and Piura, 2012).

The quantity and location of lesions in the nine cases reviewed varied considerably. A third of brain metastatic lesions were solitary, a third were multiple, and a third were unreported. Given that the route of spread is primarily hematological when metastatic to the brain, the lesions demonstrated wide spatial distribution.

The treatments for brain metastasis include: WBRT, excisional surgery (i.e. craniotomy), radiosurgery, and chemotherapy. While metastatic brain tumors are the most common intracranial tumor (typically from the lung, breast, renal, and gastrointestinal cancers), treatment varies according to lesion number, accessibility, and overall prognosis. There is no standard of care for USC brain metastasis given the paucity of cases, although general principles from neurosurgery may be followed. Traditionally, solitary brain lesions would undergo resection followed by WBRT and multiple lesions would receive WBRT (Piura and Piura, 2012). In the present case series, 3 patients underwent surgical resection (1 with a solitary lesion, 1 resected one of three lesions that was causing mass effect, and 1 unspecified lesion) (Petru et al., 2001, Gulsen and Terzi, 2013, Chura et al., 2007). Only 1 patient underwent radiosurgery as part of multimodal therapy and 5 patients underwent WBRT.

Chemotherapeutic regimens for brain metastasis are difficult to select because of the paucity of data for endometrial cancer and the likelihood of concomitant systemic disease—5 of the 9 case reports had systemic disease. Additionally, previous chemotherapy agents used need to be considered, as metastatic lesions may be chemoresistant. One agent with supporting data is topotecan, known to freely cross the blood–brain barrier, with activity against lung cancer brain metastasis (Wong and Berkenblit, 2004, Langer and Mehta, 2005). Paclitaxel has also been studied for brain metastasis, in combination with WBRT, but it did not show an improvement in median survival (Glantz et al., 1999).

The treatment outcomes for these patients are difficult to interpret, as the stage, extent of disease, and individual health must be taken into consideration to judge success. However, the median survival since diagnosis of brain metastasis was poor at 5 months, which is the exact same finding that Piura et al. note in their review of 115 cases of endometrial cancer (91 with available data). This suggests that perhaps mortality is due to the presence of brain metastasis and overall disease and not the histological type of cancer—although, again, with a small case series no firm conclusions should be made. Piura et al. conclude that longer survival results when multimodal therapy is used, such as surgery/radiosurgery followed by WBRT with or without chemotherapy (22 months) versus WBRT alone (2 months) or craniotomy alone (2.25 months). Our findings support this conclusion. Additionally, a randomized trial showed that surgical resection plus radiotherapy results in better survival and quality of life compared to radiotherapy alone for solitary brain metastases (Patchell et al., 1990). Of note, this study included 48 patients with Karnofsky performance scores > 70% and primary cancers from lung, breast, GI, GU, and melanoma. When patient status is otherwise reassuring, especially in the presence of a solitary lesion, we support multimodal therapy including surgical resection.

Conclusion

This is the ninth case report of USC brain metastasis published in the literature. Although it is an uncommon type of uterine carcinoma, this case review suggests that USC resembles other endometrial cancers in regard to its high-grade nature, interval to brain metastasis, survival, and treatment outcomes. However, the scarcity of reported cases necessitates highly individualized therapy, as there is no standard of management. When appropriate, it seems that multimodal therapy offers the best hope.

Conflicts of interest statement

The authors report no conflict of interest.

Contributor Information

Tania Sierra, Email: tania.sierra@mssm.edu.

Long Nguyen, Email: long.nguyen@mssm.edu.

Justin Mascitelli, Email: justin.mascitelli@mssm.edu.

Tamara Kalir, Email: tamara.kalir@mssm.edu.

David Fishman, Email: david.fishman@mssm.edu.

References

- Boruta D.M., Gehrig P.A., Fader A.N., Olawaiye A.B. Management of women with uterine papillary serous cancer: a Society of Gynecologic Oncology (SGO) review. Gynecol. Oncol. Oct 2009;115(1):142–153. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2009.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chura J.C., Marushin R., Boyd A., Ghebre R., Geller M.A. Argenta PA: Multimodal therapy improves survival in patients with CNS metastasis from uterine cancer: a retrospective analysis and literature review. Gynecol. Oncol. 2007;107(1):79–85. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2007.05.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Comert C.E., Bildaci T.B., Karakaya B.K., Tarhan N.C., Ozen O., Gulsen S. Outcomes in 12 gynecologic cancer patients with brain metastasis: a single center's experience. Turk. J. Med. Sci. 2012;42:385–394. [Google Scholar]

- Dietrich C.S., III, Modesitt S.C., DePriest P.D., Ueland F.R., Wilder J., Reedy M.B., Pavlik E.J., Kryscio R., Cibull M., Giesler J., Manahan K., Huh W., Cohn D., Powell M., Slomovitz B., Higgins R.V., Merritt W., Hunter J., Puls L., Gehrig P., van Nagell J.R., Jr. The efficacy of adjuvant platinum-based chemotherapy in Stage I uterine papillary serous carcinoma (UPSC) Gynecol. Oncol. Dec 2005;99(3):557–563. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2005.07.104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gien L.T., Kwon J.S., D'Souza D.P. Brain metastases from endometrial carcinoma: a retrospective study. Gynecol. Oncol. 2004;93:524–528. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2004.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glantz M., Choy H., Chakravarthy A. A randomized phase III trial of concurrent paclitaxel and whole brain radiotherapy (WBRT) vs. WBRT alone for brain metastases. Proc. Am. Soc. Clin. Oncol. 1999;18:140a. (abstract 535) [Google Scholar]

- Gulsen S., Terzi A. Multiple brain metastases in a patient with uterine papillary serous adenocarcinoma: treatment options for this rarely seen metastatic brain tumor. Surg. Neurol. Int. Aug 28 2013;4:111. doi: 10.4103/2152-7806.117176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langer C.J1., Mehta M.P. Current management of brain metastases, with a focus on systemic options. J. Clin. Oncol. Sep 1 2005;23(25):6207–6219. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.03.145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patchell R.A., Tibbs P.A., Walsh J.W., Dempsey R.J., Maruyama Y., Kryscio R.J. A randomized trial of surgery in the treatment of single metastases to the brain. N. Engl. J. Med. 1990;322:494–500. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199002223220802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petru E., Lax S., Kurschel S., Gücer F., Sutter B. Long-term survival in a patient with brain metastases preceding the diagnosis of endometrial cancer. Report of two cases and review of the literature. J. Neurosurg. May 2001;94(5):846–848. doi: 10.3171/jns.2001.94.5.0846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piura E., Piura B. Brain metastases from endometrial carcinoma. ISRN Oncol. 2012;2012:581749. doi: 10.5402/2012/581749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Talwar S., Cohen S. Her-2 targeting in uterine papillary serous carcinoma. Gynecol. Oncol. Case Rep. 2012;2(3):94–96. doi: 10.1016/j.gynor.2012.05.003. (May 8) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong E.T., Berkenblit A. The role of topotecan in the treatment of brain metastases. Oncologist. 2004;9(1):68–79. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.9-1-68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]