Abstract

We report a case of cardiogenic shock, believed to be secondary to stress-induced cardiomyopathy, managed by an Impella 2.5 assist device. Apical ballooning pattern was evident on left ventriculogram with no significant coronary artery disease on coronary angiography. Cardiogenic shock was initially managed medically with inotropes and vasopressors, but because the patient was clinically deteriorating, an Impella 2.5 left ventricular assist device was implanted. Remarkable recovery occurred within 48 h of implantation with significant increase in ejection fraction and only minimal residual apical hypokinesis observed on repeat ventriculogram.

Background

Takotsubo cardiomyopathy is a transient, stress-induced variant of cardiomyopathy typically characterised by akinesis of the apical and in some cases midsegments of the left ventricle. This yields a characteristic ballooning of the left ventricular (LV) apex during systole, similar in shape to a Japanese ceramic octopus trap, ‘Takotsubo’.1 Coronary angiogram in such cases usually reveals normal to non-significant coronary artery disease in the setting of minimal cardiac biomarker elevations, if any. Of note, this acute cardiomyopathy has a broad spectrum of clinical presentations ranging from isolated chest pain to florid pulmonary oedema and cardiogenic shock. It is generally transient and in most cases managed with circulatory support when needed until spontaneous recovery.2 3 It is debated whether the use of vasoactive medications for circulatory support may actually lead to a detrimental effect through increasing the catecholamine surge that is believed to be the main pathophysiology behind stress-induced cardiomyopathy. This may lead us to the use of device-based rather then drug-based circulatory support.

Multiple devices for cardiovascular support are available and have been used in such cases. Of these, the intra-aortic balloon pump (IABP) is the oldest and most widely used. The limited cardiac output augmentation, however, limits its use to a select population. The Impella 2.5 assist device (Abiomed Inc, Danvers, Massachusetts, USA) is considered the smallest LV assist device and can augment cardiac output by up to 2.5 L/min. It is implanted via a percutaneous approach with a relatively low-side-effect profile.

Case presentation

A 65-year-old African-American woman with a medical history of hypertension and hypothyroidism presented to the emergency department with shortness of breath and generalised weakness that started 6 h prior to presentation. She was found to be in shock with blood pressure of 65/52 mm Hg. Further diagnostic tests revealed elevated troponin I of 0.326 ng/mL and N-terminal pro-brain natriuretic peptide (NT-proBNP) of 13 016 pg/mL in addition to pulmonary congestion and cardiomegaly on chest X-ray. ECG revealed atrial fibrillation with a ventricular rate of 102 and T-wave inversions in the lateral leads. Inotropic and vasopressor support was initiated with norepinephrine and dobutamine, followed by dopamine infusions, as the patient's hypotension was recalcitrant. She was transferred to the cardiac catheter laboratory emergently. Coronary angiography revealed no significant coronary artery disease. However, a left ventriculogram demonstrated severely depressed LV systolic function with an estimated ejection fraction (EF) of 10–15%. Apical akinesis and ballooning during systole together with hyperkinetic basal segments were observed and confirmed with echocardiography (videos 1 and 2). The pattern was suggestive of takotsubo cardiomyopathy presumably attributed to social stressors later revealed by the patient. Right heart catheterisation demonstrated elevated right-sided pressures with a wedge pressure of 43 mm Hg, cardiac output 4.6 L/min and a cardiac index 1.97 L/min/m² on inotropes.

Video 1.

Echocardiography study showing apical akinesis and ballooning during systole together with hyperkinetic basal segments.

Video 2.

Definity contrast echocardiography study confirming the picture of takotsubo cardiomyopathy.

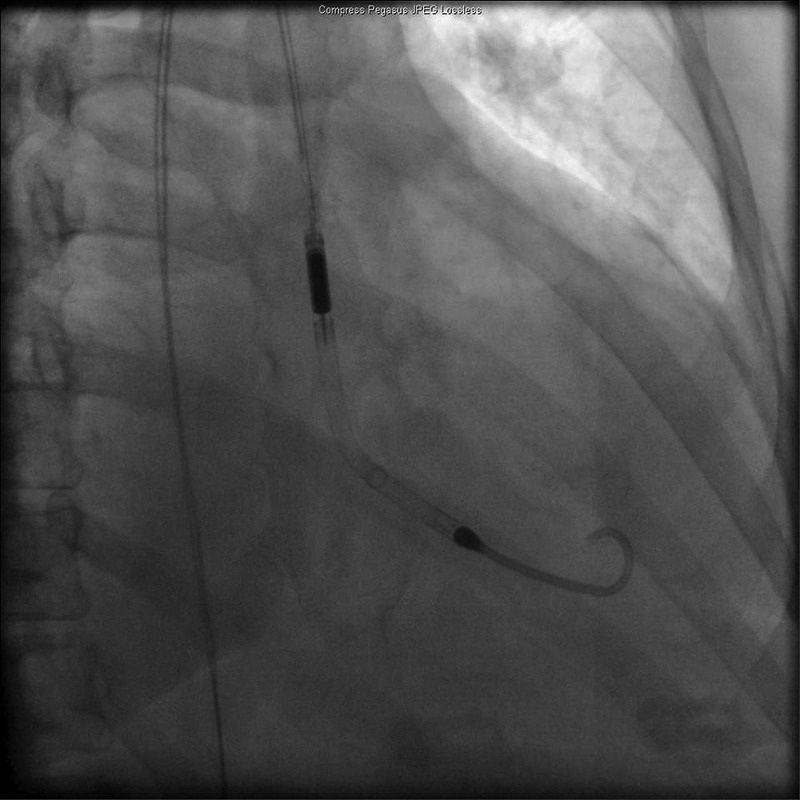

The patient developed worsening respiratory distress requiring intubation for respiratory support. In light of the sustained haemodynamic compromise, an Impella 2.5 device was inserted to support cardiac output (figure 1). It was set at P8 with output of 2.4 L/min. The device was secured in place, and the patient was then transferred to the cardiac intensive care unit for further monitoring and management.

Figure 1.

Fluoroscopy showing Impella 2.5 left ventricular assist device in left ventricle.

In the cardiac intensive care unit, the patient was initiated on amiodarone infusion after transoesophageal echocardiography revealed no left atrial appendage thrombi. Electrical cardioversion was unsuccessful.

Outcome and follow-up

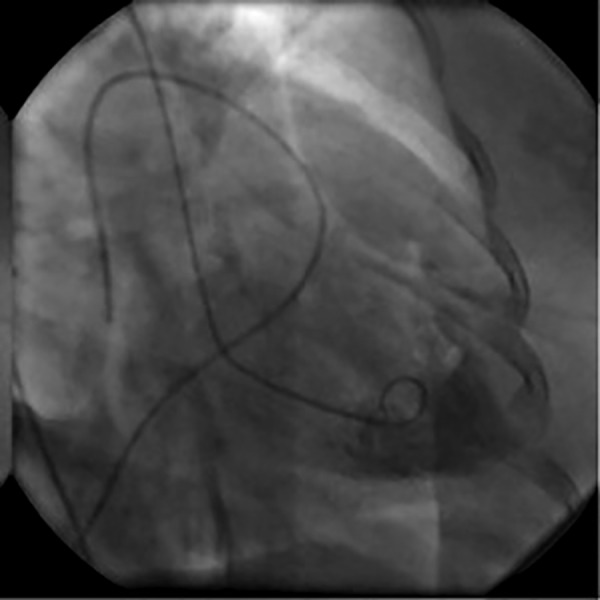

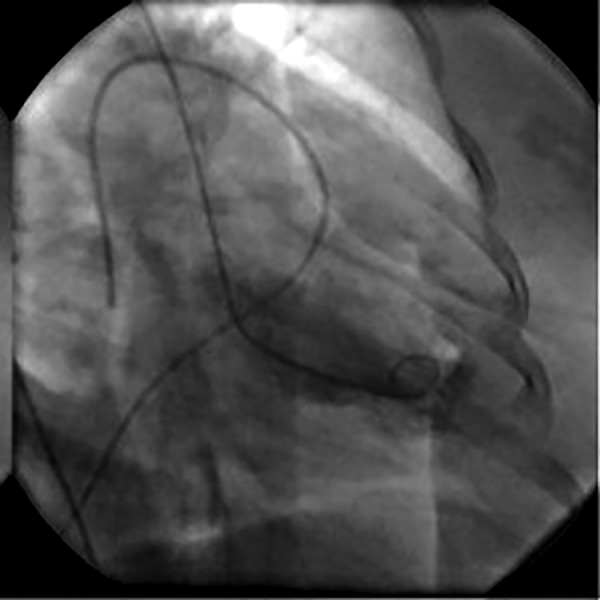

Over the following 48 h, the patient demonstrated significant clinical improvement enabling weaning off all respiratory and inotropic support. The Impella Recover LP 2.5 was removed 2 days later in the cardiac catheterisation laboratory. Repeat left ventriculogram was performed, demonstrating significant improvement of systolic function (estimated EF of 35–40%) with only residual apical hypokinesis (figures 2 and 3). The patient's renal function also normalised, and she was discharged on day 6 of admission in stable condition.

Figure 2.

Day 3 left ventriculogram; diastolic frame.

Figure 3.

Day 3 left ventriculogram; systolic frame revealing improved contractility and ejection fraction.

Discussion

Takotsubo syndrome remains an intriguing entity of cardiomyopathy and is attracting growing attention in the medical literature.4 It was first described in Japan in 1990 when the peculiar heart shape of apical ballooning and a narrow base on left ventriculogram was reminiscent of the Japanese octopus trap (takotsubo).1 The syndrome is most commonly reported in women (9:1) in the age group of 60–75, but may rarely occur in younger age groups (<3% of reported cases <50 years of age).3 5

As in this case report, the presentation is usually preceded by an episode of severe physical or emotional stress such as the loss of a loved one, accidents, surgical procedures or illicit drug use.6 This patient had recently lost her daughter followed by her son-in-law and was then caring for their children. An overall prevalence of 1.2% of stress-induced cardiomyopathy among patients initially diagnosed with acute myocardial infarction (AMI) was reported in a European study. This percentage increased to 4.9% when adjusted to the female sex.7

In the USA, an estimated prevalence of 0.02% among all hospital admissions is reported, of mostly older women with a history of anxiety, hyperlipidaemia, and tobacco and alcohol use.8 This reported case was consistent with the above profile with an age of 65 and a history of anxiety and alcohol use.

In 2010, Sharkey et al2 reported an identifiable trigger in 88% of cases in a prospective cohort involving 136 patients. In-hospital mortality was 2% and recurrence rate was 5%. New onset regional wall motion abnormalities in the absence of obstructive coronary artery disease have been previously described in association with myocarditis, coronary spasm, pheochromocytoma and subarachnoid haemorrhage. Distinctive features of takotsubo syndrome, however, include LV apical and anterior wall dyskinesia, LV base hyperkinesia, ST segment and T wave changes on ECG with no evidence of obstructive coronary artery disease on coronary angiography.2–4

The pathophysiology of the syndrome is poorly understood although several theories have been postulated. Neuroendocrine, hormonal, neuropsychological and vascular causes have been proposed among which the catecholamine surge-mediated cardiomyopathy is the most widely accepted.7

Revised in 2008, the Mayo clinic established four criteria for the diagnosis of takotsubo syndrome. These include (1) transient hypokinesis, akinesis or dyskinesis in the LV midsegments with or without apical involvement; regional wall motion abnormalities that extend beyond a single epicardial vascular distribution; and frequently, but not always, a stressful trigger; (2) the absence of obstructive coronary disease or angiographic evidence of acute plaque rupture; (3) new ECG abnormalities (ST segment elevation and/or T-wave inversion) or modest elevation in cardiac troponin; and (4) the absence of pheochromocytoma and myocarditis.3 Other findings that may support the diagnosis are minimal elevations of cardiac biomarkers, relatively rapid recovery and the presence of a preceding emotional or physical stressor.3

Although the diagnosis requires a negative coronary angiogram, some authors have attempted to identify distinctive ECG features that may help differentiate the condition from actual AMI. In 2012, Kosuge et al9 proposed that in takotsubo presentations, negative T waves exhibited greater maximum amplitudes and more diffuse lead distribution. They also reported that the presence of positive T waves on aVR lead and lack of negative T waves on V1 lead exhibited 94.5% accuracy in the diagnosis of takotsubo cardiomyopathy.9

Non-invasive imaging can play a crucial role both in the initial diagnosis and later follow-up of patients with takotsubo syndrome. Echocardiography can reveal the anteromedial and apical dyskinesia with the basal hyperkinesia typical of the syndrome. It also provides assessment of the global LV systolic function.5 Cardiac MRI may reveal oedema in a pattern that does not follow vascular territories, and can differentiate the condition from AMI by the absence of delayed enhancement in gadolinium studies.10

Treatment of takotsubo syndrome is mainly supportive with special care for controlling complications including cardiogenic shock (6.5%), heart failure (3.8%), intracavitary clot formation (3.8%), thromboembolism and ventricular arrhythmias.11 Currently, there are insufficient data to support primary or secondary prophylactic anticoagulation for patients with takotsubo syndrome.12

Patients in cardiogenic shock require prompt haemodynamic support to maintain end organ perfusion. This is usually achieved by using vasoactive medications such as catecholamines or inotropic agents such as dobutamine. The clinical challenge now arises as catecholamine surge is believed to contribute to the pathophysiology of stress-induced cardiomyopathy.7 Takotsubo cardiomyopathy has also been reported after dobutamine infusion.13 We believe, in such situations, use of mechanical support devices may provide more benefit compared with using medications that may worsen the cardiomyopathy. Of these, the two major modalities are IABP and internally implanted LV assist devices. IABP provides augmentation of diastolic coronary perfusion, decrease in LV afterload and support of peripheral perfusion, factors that create favourable conditions for recovery. In many cases, however, IABP support does not provide adequate haemodynamic support. In such cases, LV assist devices may play a significant role.14 Of these, the Impella 2.5, considered the smallest available LV assist device, can provide cardiac output augmentation of up to 2.5 L/min.

We elected to implant an Impella 2.5 LV assist device in our patient for haemodynamic support and as a bridge to recovery. Within 48 h of device implantation, the patient's haemodynamic parameters demonstrated significant improvement. She was weaned off all respiratory and circulatory support. Repeat LV ventriculogram revealed significant LV systolic function improvement (EF of 35% from 10% on presentation) with only residual apical hypokinesis. The Impella device was removed on day 2 without complications. A similar case of cardiogenic shock secondary to takotsubo cardiomyopathy with the use of Impella LV assist device was reported by Hamid et al.15

Learning points.

Takotsubo syndrome is an increasingly reported cardiomyopathy with a spectrum of presentations ranging from mild chest pain to cardiogenic shock, and in most cases it mimics acute coronary syndrome, requiring coronary angiography, which then aides in diagnosis.

Cases presenting with or complicated by cardiogenic shock may require prompt haemodynamic support.

As vasoactive medications used for haemodynamic support may worsen this unique entity of cardiomyopathy, the prompt use of the Impella LV assist device may represent a rescue bridge to recovery in severe cases of takotsubo cardiomyopathy, a finding that warrants further research.

Footnotes

Contributors: AR collected the case data and wrote the first draft of the manuscript. MS contributed to the analysis of the data and edited the manuscript. SW contributed to critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content. TS was responsible for the final revision of the manuscript and approval of the final version submitted.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Sharkey SW, Lesser JR, Maron BJ. Cardiology patient page. Takotsubo (stress) cardiomyopathy. Circulation 2011;124:e460–2. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.052662 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sharkey SW, Windenburg DC, Lesser JR et al. Natural history and expansive clinical profile of stress (tako-tsubo) cardiomyopathy. J Am Coll Cardiol 2010;55:333–41. 10.1016/j.jacc.2009.08.057 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Prasad A, Lerman A, Rihal CS. Apical ballooning syndrome (Tako-Tsubo or stress cardiomyopathy): a mimic of acute myocardial infarction. Am Heart J 2008;155:408–17. 10.1016/j.ahj.2007.11.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Golabchi A, Sarrafzadegan N. Takotsubo cardiomyopathy or broken heart syndrome: a review article. J Res Med Sci 2011;16:340–5. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lemos AET, Junior Araújo AL, Lemos MT et al. Broken-heart syndrome (Takotsubo syndrome). Arq Bras Cardiol 2008;90:e1–3. 10.1590/S0066-782X2008000100011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kaballo MA, Yousif A, Abdelrazig AM et al. Takotsubo cardiomyopathy after a dancing session: a case report. J Med Case Rep 2011;5:533 10.1186/1752-1947-5-533 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Previtali M, Repetto A, Panigada S et al. Left ventricular apical ballooning syndrome: prevalence, clinical characteristics and pathogenetic mechanisms in a European population. Int J Cardiol 2009;134:91–6. 10.1016/j.ijcard.2008.01.037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Deshmukh A, Kumar G, Pant S et al. Prevalence of Takotsubo cardiomyopathy in the United States. Am Heart J 2012;164:66–71.e1. 10.1016/j.ahj.2012.03.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kosuge M, Ebina T, Hibi K et al. Differences in negative T waves between takotsubo cardiomyopathy and reperfused anterior acute myocardial infarction. Circ J 2012;76:462–8. 10.1253/circj.CJ-11-1036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fernández-Pérez GC, Aguilar-Arjona JA, de la Fuente GT et al. Takotsubo cardiomyopathy: assessment with cardiac MRI. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2010;195:W139–45. 10.2214/AJR.09.3369 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vasconcelos JTP, Martins S, Sousa JF et al. [Takotsubo cardiomiopathy. A rare cause of cardiogenic shock simulating acute myocardial infarction]. Arq Bras Cardiol 2005;85:128–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mitsuma W, Kodama M, Ito M et al. Thromboembolism in Takotsubo cardiomyopathy. Int J Cardiol 2010;139:98–100. 10.1016/j.ijcard.2008.06.089 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mosley WJ, Manuchehry A, McEvoy C et al. Takotsubo cardiomyopathy induced by dobutamine infusion: a new phenomenon or an old disease with a new name. Echocardiography 2010;27:E30–3. 10.1111/j.1540-8175.2009.01089.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Seyfarth M, Sibbing D, Bauer I et al. A randomized clinical trial to evaluate the safety and efficacy of a percutaneous left ventricular assist device versus intra-aortic balloon pumping for treatment of cardiogenic shock caused by myocardial infarction. J Am Coll Cardiol 2008;52:1584–8. 10.1016/j.jacc.2008.05.065 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hamid T, Eichhöfer J, Fraser D et al. Use of the Impella left ventricular assist device as a bridge to recovery in a patient with cardiogenic shock related to takotsubo cardiomyopathy. J Clin Exp Cardiolog 2013;4:246 10.4172/2155-9880.1000246 [DOI] [Google Scholar]