Abstract

A 40-year-old heroin smoking man presented with acute onset severe shortness of breath. Radiological investigations revealed an unexpected loculated pneumothorax. Respiratory physicians inserted a chest drain which relieved his breathlessness. His exercise tolerance is much improved 6 months on. The side effects of smoking illicit substances are poorly understood. There is a growing trend for drug users to smoke rather than intravenously inject. It is therefore important for clinicians to be aware of the associated morbidity. The authors believe this is the first ever reported case of loculated pneumothorax associated with heroin smoking.

Background

There were an estimated 262 000 opiate drug users in England in 2011; the majority of them using heroin.1 Heroin can be administered intravenously or smoked/inhaled. Trends show there has been an increase in the proportion of users smoking compared to injecting,2 likely due to the lowered risk of contracting blood borne diseases. Smoking heroin can, however, cause a number of pulmonary problems including non-cardiogenic pulmonary oedema, hypoxic damage to alveolar integrity and opiate-induced anaphylactoid reaction.3 Owing to the changing trends, clinicians must be aware of these potential presentations.

This is a rare case of a loculated pneumothorax in a heroin user.

Case presentation

In May 2014, a 40-year-old man presented with a 1-day history of sudden dyspnoea, productive cough and associated right-sided pleuritic chest pain. There was no haemoptysis or leg swelling.

He had a medical history of hepatitis C, thrombocytopenia and multidrug-resistant HIV. He disclosed freely that he regularly smoked heroin and denied any other drug or cigarette use.

One year previously he was treated with oral antibiotics for a mild community acquired pneumonia. Ever since, he had been chronically breathless with an exercise tolerance of 100 yards, which was now reduced to five steps.

On examination, he was dyspnoeic at rest. His oxygen saturation remained 98% on room air. He had signs of a right pneumothorax with decreased air entry and hyper-resonance on percussion; there was no mediastinal shift.

Investigations

The patient declined an arterial blood gas sample due to a previous negative experience. A platelet count of 42 was the only abnormal finding on blood tests, which was chronic, and as a result of his HIV and associated highly active antiretroviral therapy.

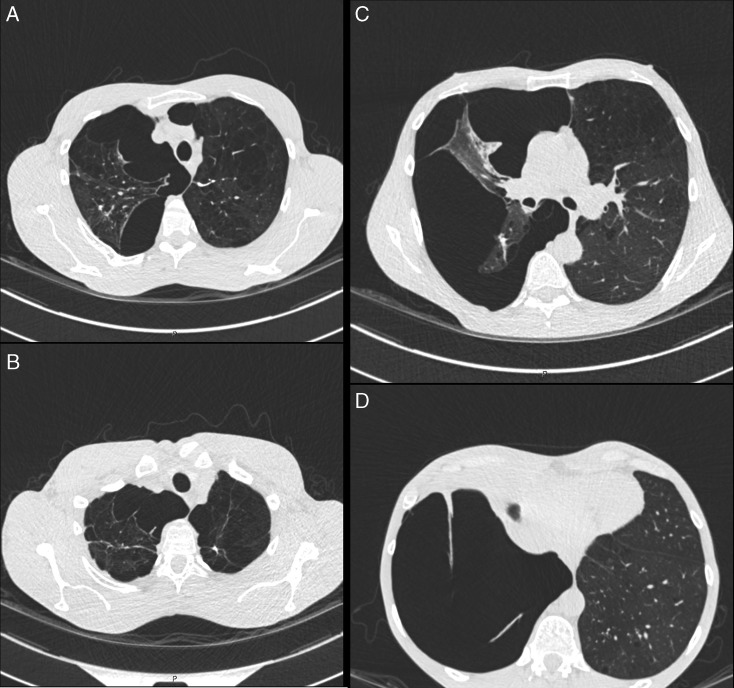

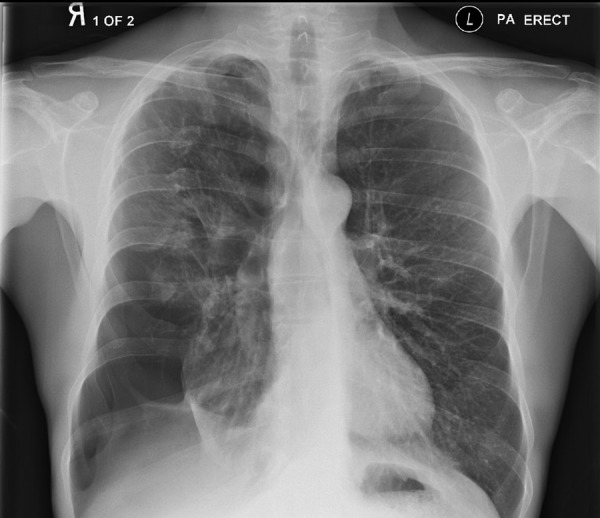

Chest X-ray revealed the presence of a large pneumothorax located in the right base (figure 1). The previous year's X-ray showed the beginnings of this finding (figure 2).

Figure 1.

Chest X-ray, extensive pneumothorax right base.

Figure 2.

Chest X-ray, approximately 1 year prior to figure 1. A small pneumothorax at the right base.

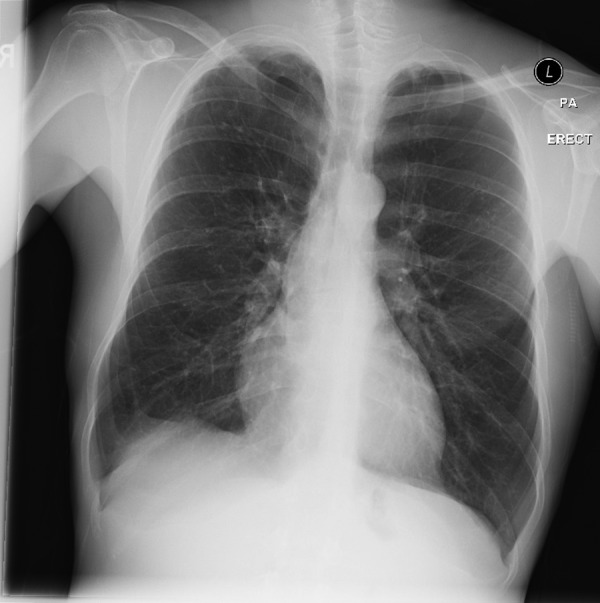

An urgent CT of the thorax (figure 3A–D) demonstrated a large right-sided loculated pneumothorax with extensive pleural adhesions at multiple locations of the pleural surface, particularly at the apex and anteriorly in the middle lobe.

Figure 3.

(A–D) Progressively lower axial CT images showing loculated pneumothorax.

Treatment

A diagnosis of organised pneumothorax associated with heroin smoking was made. The patient was moved to the resuscitation department and respiratory physicians placed an intercostal drain in the sixth intercostal space following a platelet transfusion.

Outcome and follow-up

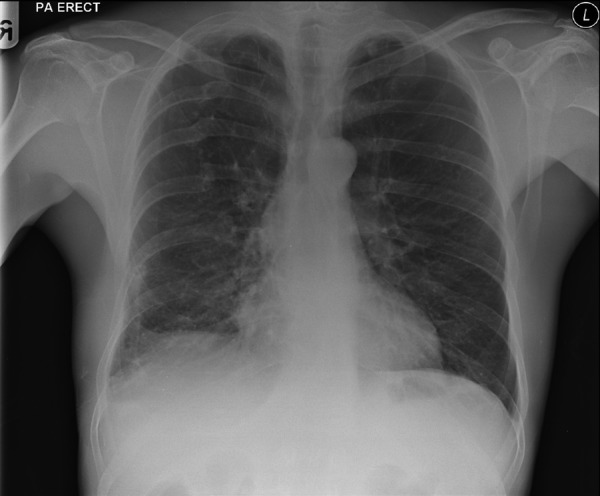

The patient was discharged after the pneumothorax resolved (figure 4). The patient reported his exercise tolerance increased dramatically and no longer needed to stop when walking on a flat surface.

Figure 4.

Chest X-ray showing resolution of right pneumothorax.

Discussion

The authors were unable to find any other cases of spontaneous pneumothorax associated with heroin smoking and believe this is the first time it has been reported.

Another possible cause for the spontaneous pneumothorax could be pneumocystis pneumonia (PCP). The authors feel this is unlikely but cannot rule it out as PCP samples were not taken at the time of the pneumothorax. The patient had never been diagnosed with PCP, and pneumothorax-associated PCP occurs only very rarely in 1.2% of HIV patients admitted to hospital.4 Our patient differs in a number of ways from previous reports as he did not present with a fever, and had no other features of infection such as diarrhoea. Changes associated with PCP occur at the apices rather than the bases of the lungs and our patient improved with a simple chest drain compared to others who required more complicated management including sclerosing therapy.5

There were an estimated 262 000 opiate drug users in England in 2011, with the majority of them using heroin.1 Heroin can be administered intravenously or smoked/inhaled. There has been a recent trend indicating an increase in the proportion of users smoking heroin rather than injecting it.2

Compared with the risks of intravenous drug use, the effects of smoking illicit substances are less well studied and publicised. Among professionals dealing with drug addiction, 50% stated that there was no health information available on the harmful effects of smoking drugs and 56% stated that apart from smoking cessation there are no other respiratory-related health interventions.6

Heroin smoking is known to cause pulmonary oedema, but the mechanisms remain unclear and include attempted inspiration against a closed glottis, hypoxic damage to alveolar integrity, neurogenic vasoactive response to stress and opiate-induced anaphylactoid reaction.3

Converting injecting drug users to smokers provides universal public health benefits7 such as decrease in blood to blood viruses, reduced systemic infection, and reduced soft tissue and venal damage. Providing foil could help reduce the risk of smoking, and increase benefits further by improving contact and engagement with drug service workers, and lower the risk of overdose.8

Owing to changing trends of heroin use, it is imperative that clinicians are aware of the potential complications. Much more work needs to be carried out on the effects of drugs on lung function, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, lung cancer and the increased risk of infectious disease.

Learning points.

Newer trends show more people are smoking drugs.

Clinicians must endeavour to attain full-drug history including drug used and administration method, and be aware of the complications of each.

Heroin smoking can lead to a complex pneumothorax.

Footnotes

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Hay G, Rael dos Santos A, Millar T. Estimates of the prevalence of opiate use and/or crack cocaine use, 2010/11: sweep 7 report. London: National Treatment Agency for Substance Misuse; Retrieved October 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bretteville AL, Skretting A. Heroin smoking and heroin using trends in Norway. Nord Stud Drug Alcohol 2010;27:5–18. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mégarbane B, Chevillard L. The large spectrum of pulmonary complications following illicit drug use: features and mechanisms. Chem Biol Interact 2013;206:444–51. 10.1016/j.cbi.2013.10.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Afessa B. Pleural effusion and pneumothorax in hospitalized patients with HIV infection: the pulmonary complications, ICU support, and prognostic factors of hospitalized patients with HIV (PIP) study. Chest 2000;117:1031–7. 10.1378/chest.117.4.1031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shanley D, Luyckx B, Haggerty M et al. Spontaneous pneumothorax in AIDS patients with recurrent pneumocystis carinii pneumonia despite aerosolized pentamidine prophylaxis. Chest 1991;99:502–4. 10.1378/chest.99.2.502 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Baron L. Promoting drug users respiratory health. Centre for Public Health, Liverpool John Moores University, 2010. Retrieved October 2014. http://www.ihra.net/files/2010/08/31/463.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kools JP. From fix to foil: the Dutch experience in promoting transition away from injecting drug use, 1991–2010.

- 8.Advisory Council on the Misuse of Drugs. Consideration of the use of foil as an intervention, to reduce the harms of heroin and cocaine. Retrieved October 2014.