Abstract

Colonic schwannomas are very rare gastrointestinal tumours originating from Schwann cells, which form the neural sheath. Primary schwannomas of the lower gastrointestinal tract are very rare and usually benign in nature. However, if they are not surgically removed, malign degeneration can occur. We report a case of a 79-year-old woman who presented to our clinic with rectal bleeding and constipation. She underwent a lower gastrointestinal tract endoscopy. A mass subtotally obstructing the lumen of the sigmoid colon was seen and biopsies were taken. Histopathological examination indicated a suspicion of gastrointestinal tumour and the patient underwent sigmoid colon resection after preoperative evaluation by laboratory analysis, abdominal ultrasonography and CT. Her postoperative course was uneventful and she was discharged on the fifth day for outpatient control. The histopathology report revealed schwannoma of the sigmoid colon. This was a case of schwannoma of the sigmoid colon that was successfully treated with total resection.

Background

A schwannoma is a neoplastic lesion histologically originating from Schwann cells, which form the neural sheath. The tumour can be found along the peripheral nerves throughout the body, but are found mostly in the head, neck, and upper and lower limbs; schwannoma of the colon is very rare. Most schwannomas are benign and asymptomatic, with non-specific symptoms, which may include pain, fatigue and fever. Symptomatic patients usually complain of rectal bleeding or signs of colonic obstruction.1 They are usually treated with radical surgical resection with margins free of disease.2 They can appear with local recurrence and malign degeneration.2 We present a case of a 79-year-old woman with sigmoid colonic schwannoma that was detected on colonoscopy, who underwent surgical resection and was diagnosed histologically.

Case presentation

A 79-year-old woman presented to our internal medicine clinic with rectal bleeding and constipation. She underwent colonoscopy at the endoscopy unit of our general surgery department; a rough mass at the sigmoid colon, covered by ulcerated mucosa that was obstructing the lumen subtotally, was seen, and multiple biopsies were performed.

Her history and physical examination revealed a lower abdominal tenderness; her only comorbidity was diabetes mellitus. Laboratory findings included normal leucocyte 11.600/mm3, haemoglobin: 10.7 g/dL, α fetoprotein: 3.22 ng/mL, CA-15.3: 16.6 U/mL, CA-19.9: 0.8 U/mL, CA-12: 7.8 U/mL and carcinoembryonic antigen 2.93 ng/mL. Abdominal ultrasound revealed a 38×35 mm hypoechoic solid lesion left of the umbilicus, suggestive of a tumour of gastrointestinal origin.

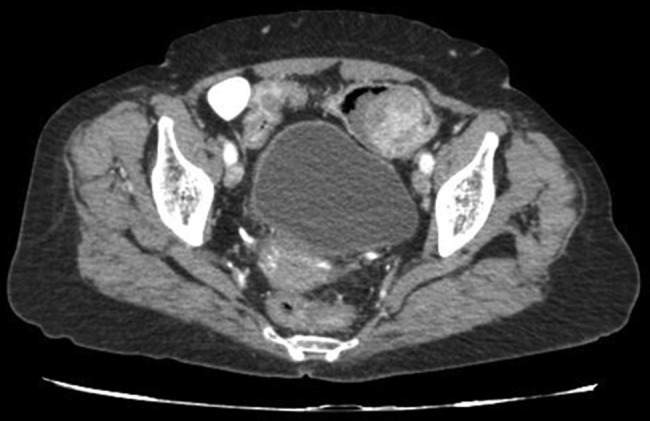

Abdominal CT revealed as Sigmoid colon cancer suspicion at about including 7 cm of intestinal segment in the colon level. A tumoural mass showing intraluminal protrusion and causing narrowing of the lumen with wall thickening was observed. Neighbourhood fatty plan is dirty and multiple lengths of lymph nodes were observed (figure 1).

Figure 1.

Abdominal CT findings revealed a round polypoid lesion with homogeneous low attenuation inside the sigmoid colon with adjacent wall thickening.

Histopathology of the endoscopic biopsy indicated a gastrointestinal tumour, and the patient underwent sigmoid colon resection and end to end anastomoses. On the fifth postoperative day, she was discharged without any complaints with a recommendation for outpatient control.

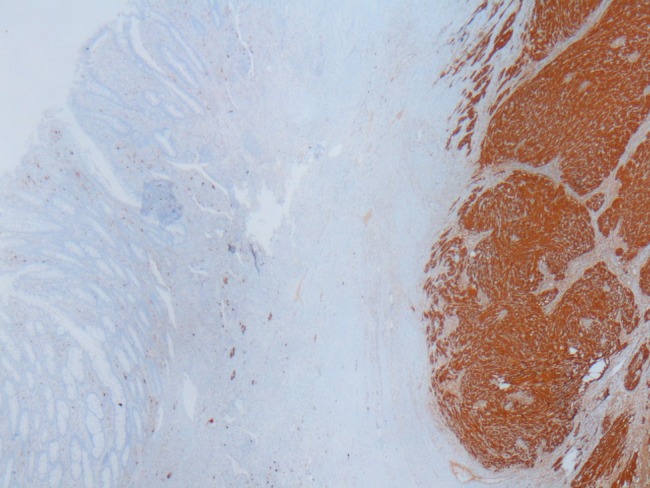

Histopathological examination of the resected gastric specimen reported it to be a 5×4×3.5 cm schwannoma of the sigmoid colon with clear surgical margins. 29 resected lymph nodes were revealed as reactive lymphoid hyperplasia. There was ulceration on the mucosa, the serosa was intact and no invasion was seen (figure 2).

Figure 2.

Macroscopic appearance of the tumour at the sigmoid colon.

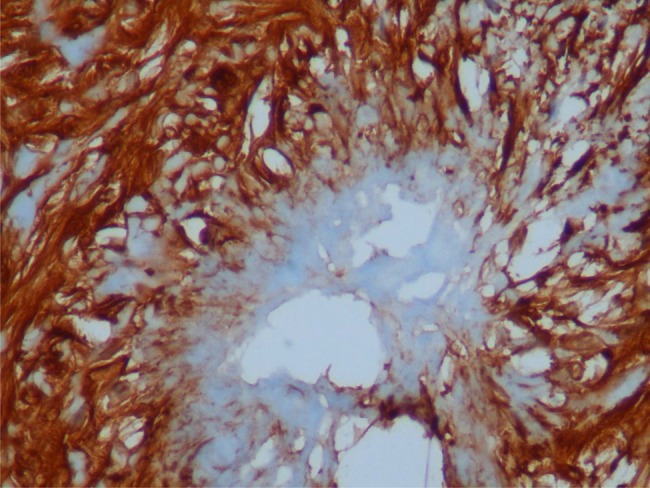

To clarify the exact diagnosis of the tumour further, immunohistochemical staining was performed. The tumour cells were negative for smooth muscle actin (SMA), desmin, CD 117, P53, myoglobulin and pan cytokeratin (CK), and strongly positive for S-100 (figure 3) and vimentin (figure 4). Ki-67 index was approximately 4–5%. Vascular structures were stained as positive with CD34. Histopathology diagnosed the specimen as schwannoma of the sigmoid colon.

Figure 3.

Schwannoma area at the right side showing diffuse S100 positivity. S100×2.

Figure 4.

Rosette formation; schwannoma cells expressing S100 and vimentin positivity. S100×40.

Differential diagnosis

Gastrointestinal stromal tumour was excluded from the differential diagnosis by CD 117 negativity.

Treatment

We performed sigmoid colon resection and end to end anastomoses as the surgical procedure.

Outcome and follow-up

On the fifth day, the patient discharged without any complaints with recommendation for outpatient and medical oncology control. She did not have any neoadjuvant therapy. For keeping a check on local or distal recurrence, a total body CT scan was planned every 6 months and a lower gastrointestinal tract endoscopy was planned yearly.

Discussion

In 1910, Verocay first described the benign rare neoplasm of ectodermic origin growing from the neural sheath1; schwannomas were histologically characterised by Verocay corpuscles, a lymphoid cuff and a spiral-like form consisting of densely arrayed spindle-shaped cells, palisade arrangements and loose reticular networks of cells.3 4

Schwannomas are usually slow-growing benign tumours. If a schwannoma is not removed, it presents a possibility of malignant degeneration.1–3 5 6 Schwannomas are seen in sexes equally and are mostly found after the sixth and seventh decades of life, but can appear at any age.

The stomach (83%) and the small intestine (12%) are the most frequently involved regions of the gastrointestinal tract.3 Cases are usually asymptomatic, but in some, tenesmus, rectal bleeding and pain can be experienced.3 4 7

Macroscopically, schwannomas tend to share the gross morphological features of lobulated and well-delimited tumours with a cystic pattern and, rarely, may be hard, solid, ulcerated or calcified.8 In the gastrointestinal system they more frequently arise from the Auerbach’s plexus than from Meissner's.4 The cells of the schwannoma are immunoreactive to S-100 protein and vimentin, but are negative for SMA, desmin, CD 117, P53, myoglobulin and pan CK.3 4 9 In the differential diagnosis of gastrointestinal stromal tumour, it shows positivity to CD117 and CD34 but negativity to S-100 protein.10

The Ki-67 proliferative index (MIB-1) is recommended as an indicator of malignancy, as its positivity (≥5%) is strictly correlated with greater tumour aggressiveness and more than 10% is considered to be malignant. Ki-67 index was about 4–5% in our case. A high risk of metastasis and recurrence has to be associated with a mitotic activity rate >5 mitoses per field at high magnification and a tumour size bigger than 5 cm. Benign lesions are characterised as having a low rate of mitosis, and the absence of atypical mitotic figures and nuclear hyperpigmentation.3 Distant metastasis has been reported in 2% of cases.11

Currently, complete surgical resection of the tumour with margins free of disease is the best therapeutic choice.12 Surgical management depends on the tumour size, location and histopathological pattern. Routine radiotherapy or adjuvant chemotherapy has not been used. Histopathological examination of preoperative colonoscopic biopsy may be difficult and immunohistochemistry is necessary to diagnose schwannoma correctly. In our case, a tumour at the sigmoid colon was successfully resected and no lymph nodes were involved.

Learning points.

Endoscopic biopsy examinations are not sufficient for exact diagnosis at lower gastrointestinal tract endoscopy.

Immunohistochemical evaluation is usually needed.

Stains such as DOG-1 have to be used to exclude GIST.

Complete surgical resection of the tumour with margins free of disease is the standard treatment for colonic schwannomas.

Footnotes

Competing interests: None.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Zippi M, Pica R, Scialpi R et al. Schwannoma of the rectum: a case report and literature review. World J Clin Cases 2013;1:49–51. 10.12998/wjcc.v1.i1.49 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fotiadis CI, Kouerinis IA, Papandreou I et al. Sigmoid schwannoma: a rare case. World J Gastroenterol 2005;11:5079–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nonose R, Lahan AY, Santos Valenciano J et al. Schwannoma of the colon. Case Rep Gastroenterol 2009;3:293–9. 10.1159/000237736 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tsunoda C, Kato H, Sakamoto T et al. A case of benign schwannoma of the transverse colon with granulation tissue. Case Rep Gastroenterol 2009;3:116–20. 10.1159/000214837 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Daimaru Y, Kido H, Hashimoto H et al. Benign schwannoma of the gastrointestinal tract: a clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical study. Hum Pathol 1988;19:257–64. 10.1016/S0046-8177(88)80518-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lauwers GY, Erlandson RA, Casper ES et al. Gastrointestinal autonomic nerve tumors: a clinicopathological, immunohistochemical, and ultrastructural study of 12 cases. Am J Surg Pathol 1993;17:887–97. 10.1097/00000478-199309000-00004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kanneganti K, Patel H, Niazi M et al. Cecal schwannoma: a rare cause of gastrointestinal bleeding in a young woman with review of literature. Gastroenterol Res Pract 2011;2011:142781 10.1155/2011/142781 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tomozawa S, Masaki T, Matsuda K et al. A schwannoma of the cecum: case report and review of japanese schwannomas in the large intestine. J Gastroenterol 1998;33:872–5. 10.1007/s005350050191 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Braumann C, Guenther N, Menenakos C et al. Schwannoma of the colon mimicking carcinoma: a case report and literature review. Int J Colorectal Dis 2007;22:1547–8. 10.1007/s00384-006-0264-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fletcher CD, Berman JJ, Corless C et al. Diagnosis of gastrointestinal stromal tumors: a consensus approach. Int J Surg Pathol 2002;10:81–9. 10.1177/106689690201000201 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Das Gupta TK, Brasfield RD. Tumors of peripheral nerve origin: benign and malignant solitary schwannomas. CA Cancer J Clin 1970;20:228–33. 10.3322/canjclin.20.4.228 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Maciejewski A, Lange D, Wloch J. Case report of schwannoma of the rectum–clinical and pathological contribution. Med Sci Monit 2000;6:779–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]