Abstract

A series of N-(3-ethynyl-2,4-difluorophenyl)sulfonamides were identified as new selective Raf inhibitors. The compounds potently inhibit B-RafV600E with low nanomolar IC50 values and exhibit excellent target specificity in a selectivity profiling investigation against 468 kinases. They strongly suppress proliferation of a panel of human cancer cell lines and patient-derived melanoma cells with B-RafV600E mutation while being significantly less potent to the cells with B-RafWT. The compounds also display favorable pharmacokinetic properties with a preferred example (3s) demonstrating significant in vivo antitumor efficacy in a xenograft mouse model of B-RafV600E mutated Colo205 human colorectal cancer cells, supporting it as a promising lead compound for further anticancer drug discovery.

Keywords: B-Raf, colon cancer, melanoma, kinase inhibitor, targeted therapy

The Raf serine/threonine kinases are key components of mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) cascade.1 Among three isoforms of the family (i.e., A-Raf, B-Raf, and C-Raf), mutations of B-Raf are the most frequently detected in human cancers,2 including 50–80% of melanoma,3 ∼100% of hairy cell leukemia,4 45–50% of papillary thyroid carcinoma,5 11% of colorectal cancer,3 and others. Notably, over 90% of B-Raf mutations are the substitution of valine to glutamate at residue 600 (V600E). This substitution mimics phosphorylation of the activation loop, elevating the in vitro kinase activity by up to 500–700-fold compared with its wide-type counterpart.6 Therefore, selectively inhibiting B-Raf becomes an attractive strategy for the clinical treatment of B-RafV600E-driven human cancers.7

Several classes of B-Raf inhibitors have been discovered,8,9 among which vemurafenib (1, Figure 1) and dabrafenib (2, Supporting Information) have been approved by US FDA for the treatment of metastatic and unresectable melanoma harboring B-Raf mutations.10,11 Many other clinical investigations of B-Raf inhibitors alone or in combination with other kinase inhibitors, immunotherapies, or conventional chemotherapies, are ongoing, for the treatment of metastatic colorectal cancer, papillary thyroid carcinoma, and metastatic nonsmall cell lung cancer.12

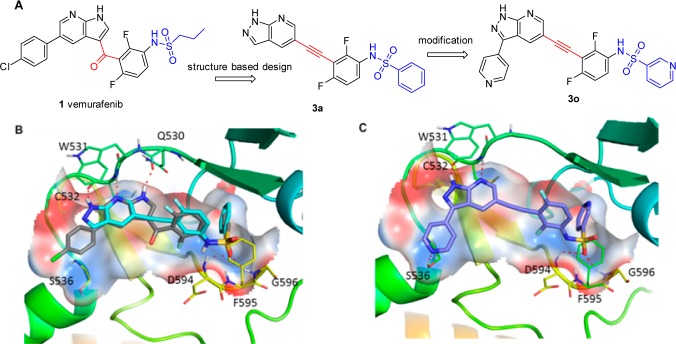

Figure 1.

Design of new Raf inhibitors (A). Predicted binding model of 3a (blue) superimposed to vemurafenib (gray) in a crystal structure of B-Raf (PDB: 3OG7) (B). Predicted binding model of 3o with B-Raf (C).

However, intrinsic or acquired resistance against current B-Raf inhibitor therapies becomes a major challenge.13 For instance, a majority of colorectal cancer patients display inherent resistance against vemurafenib, although they were detected to harbor B-RafV600E mutation.14 The exact mechanism for the resistance remains elusive, but development of new inhibitors with differentiated chemical scaffolds may be a valuable strategy to overcome or delay the occurrence of this challenging medical dilemma. Herein, we describe the design and optimization of N-(3-ethynyl-2,4-difluorophenyl)sulfonamide derivatives as new selective Raf inhibitors.

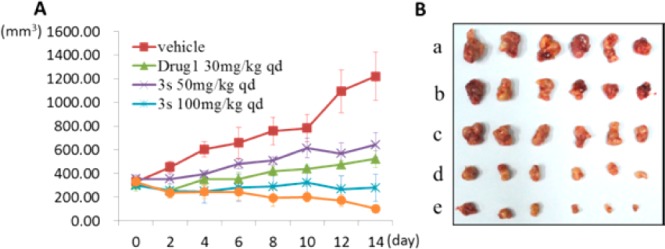

An X-ray crystallographic analysis reveals that vemurafenib binds to B-Raf with a DFG-in and αC-helix-out inactive conformation.11 The 1H-pyrrolo[2,3-b]pyridine core forms two pairs of hydrogen bonds with the backbone amide of Cys532 and the backbone carbonyl of Gln530, respectively (Figure 1B). The sulfonamide may form two extra hydrogen bonds with Asp594 and Gly596, respectively, and the propyl group is critical for selectivity by occupying a small lipophilic pocket enlarged by an outward shift of αC-helix of the protein. On the basis of these observations, we rationally designed a series of N-(3-ethynyl-2, 4-difluorophenyl)sulfonamides (3) as new B-Raf inhibitors, in which a druglike scaffold 1H-pyrazolo[3,4-b]pyridine was utilized as the crucial hinge-binding moiety; a conformation and distance favorable ethynyl linker was introduced between the hinge-binding core and a difluorophenyl group; and the sulfonamide moiety was preserved to form the important hydrogen bonding networks with the protein. Instead of using an alkyl substituent in the sulfonamide (i.e., a propyl group in vemurafenib), an aryl group was introduced to capture a potential CH−π interaction with Phe595 (Figure 1B).

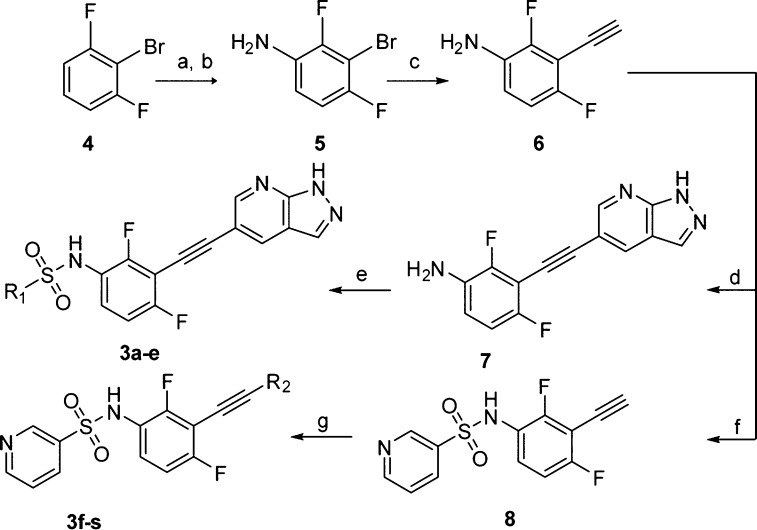

The designed compounds were synthesized by using Sonogashira coupling as the key steps (Scheme 1). Briefly, the intermediate 6 was readily prepared from 2-bromo-1,3-difluorobenzene (4) through consequent procedures including a standard nitration, a stannous chloride mediated reduction, a modified Sonogashira coupling, and a detrimethylsilylation.15 The hinge-binding 1H-pyrazolo-[3,4-b]pyridine was then introduced via another Sonogashira reaction. A direct arylsulfonylation of 7 with different arylsulfonyl chlorides yielded the final sulfonamides 3a–3e with good to moderate yields. Compounds 3f–3s were prepared through similar protocols (Supporting Information).

Scheme 1. Synthesis of Compounds 3a–3s.

Reagents and conditions: (a) con. H2SO4, KNO3, rt, 2.0 h, 91%; (b) SnCl2, con. HCl, EtOH, reflux, 93%; (c) (i) Pd(dba)2, CuI, ethynyltrimethylsilane, t-(Bu)3P, K2CO3, dry THF, 120 °C, 48 h; (ii) n-(Bu)4NF, THF, rt, 1 h, 46%; (d) 6-bromo-3H-pyrazolo[3,4-b]pyridine, Pd(dba)2, CuI, t-(Bu)3P, K2CO3, dry THF, 120 °C, 24 h, 63%; (e) R1Cl, pyridine, dry DCM, rt, overnight, 39–90%; (f) pyridine-3-sulfonyl chloride, pyridine, dry DCM, rt, overnight, 93%; (g) R2Br, Pd(dba)2, CuI, t-(Bu)3P, K2CO3, dry THF, 120 °C, 24 h, 47–70%.

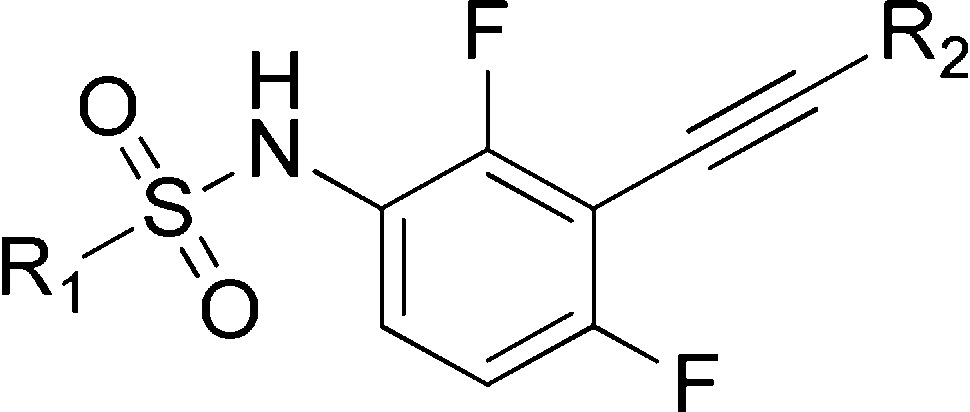

A preliminary computational study suggested that 3a might bind to the DFG-in B-RafV600E with a similar mode to that of vemurafenib (Figure 1B). A biological evaluation showed that 3a indeed inhibited B-RafV600E kinase with an IC50 value of 0.149 μM in an FRET-based Z′Lyte assay.16 It also selectively suppresses the proliferation of Colo205 human colorectal cancer cells harboring B-RafV600E mutation with an IC50 value of 2.103 μM but is obviously less potent against the growth of HCT116 colorectal carcinoma cells with B-RafWT (IC50 > 10 μM) (Table 1). These results support that 3a may serve as a lead compound for new B-RafV600E inhibitor discovery. An extensive structure–activity relationship investigation was then conducted, and the results revealed that an F substitution at different positions of R1-phenyl ring in 3a could achieve diverse impact on the B-RafV600E inhibitory activity. For instance, ortho-F substituted analogue 3b displays a similar B-RafV600E inhibitory activity to that of 3a, while the meta-fluoro compound 3c is 2–3-fold more potent, with an IC50 value of 0.068 μM. However, when an F atom was introduced in the para-position, the resulting compound 3d was 6-fold less potent. Further study showed that the meta-fluoro phenyl group in 3c could be replaced by a 3-pyridyl moiety (3f) to display almost identical potency against B-RafV600E, with an IC50 value of 0.051 μM. However, the 2-pyridyl analogue (3e) is about 10-times less potent. It is hypothesized that 3c and 3f may induce a conformational rearrangement of the protein to generate additional hydrogen bonds between the F or N atom and the backbone of the DFG motif. A future cocrystallographic investigation will be highly valuable to demonstrate the precise interactions. Our docking study has suggested that the two pairs of hydrogen bonds formed by 1H-pyrazolo[3,4-b]pyridine in 3f with Cys532 contribute greatly to the compound’s B-RafV600E inhibition. Indeed, compound 3h lacking a hydrogen bond acceptor showed an IC50 value against B-RafV600E of 4.31 μM, which was 85-times less potent than 3f. However, the removal of a hydrogen bond donor (3i) also caused a significant loss of potency. Not surprisingly, 1H-pyrazolo[3,4-b]pyridine hinge-binding moiety could be replaced by a similar bivalent 1H-pyrrolo[2,3-b]pyridine (3g) without obviously affecting the B-RafV600E inhibitory potency. Further investigation revealed that 3-position of the 1H-pyrazolo[3,4-b]pyridine core could be substituted by a methoxyl (3j), methyl (3l), cyclopropyl (3m), or phenyl (3n) group to achieve 2–5-fold potency improvement. However, the 3-ethoxyl compound 3k is 2-times less potent than 3f. Encouragingly, when the position was substituted by a 4-pyridyl group, the resulting compound 3o displayed an IC50 value of 3.0 nM against B-RafV600E, which is 10-times more potent than vemurafenib in a parallel comparison. Compound 3o also displayed a 4-time stronger antiproliferative activity, with an IC50 value of 78 nM against B-RafV600E mutated Colo205 cancer cells and favorable selectivity with >10 μM IC50 value against HCT116 cancer cells with B-RafWT. It was predicted an extra hydrogen bond between N atom of the 4-pyridinyl group and the side chain of Ser536 may contribute to this potency improvement (Figure 1C). The para-fluorophenyl analogue 3s also displayed a slightly increased potency, whereas the ortho-Cl or meta-Cl substituted compounds 3p and 3q are 8- and 7-fold less potent than 3n, respectively. Thus, 3o and 3s were selected as the representatives for further investigations.

Table 1. Enzymatic and Cellular Activities of Compounds 3a–3s.

Kinase activity assays were performed by a FRET-based Z′-Lyte assay.

The antiproliferative activities were evaluated using a MTT assay. Data are means of three independent experiments, and the variations are <20%.

The antiproliferative activity of 3o and 3s were examined against a panel of cancer cell lines and primary cancer cells derived from New Zealand metastatic melanoma patients harboring differing status of B-Raf.17,18 It was shown that 3s displayed similar antiproliferative effects against B-RafV600E mutated cancer cells to that of vemurafenib, whereas compound 3o is moderately more potent (Table 2). In contrast, none of the compounds showed obvious growth inhibition against cell lines expressing B-RafWT. It is also noteworthy that the patient-sourced melanoma cells with B-RafV600E mutation are more sensitive to the inhibitors. Both 3o and 3s inhibit the growth of NZM20 and NZM07 cells with low nanomolar IC50 values.

Table 2. Antiproliferative Activities of the Compounds against a Panel of Cancer Cells with Different Status of B-Raf.

| antiproliferation

(IC50, μM) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| cell lines | 3o | 3s | 1 |

| Lovoa | >10 | >10 | >10 |

| SK-MEL-2a | >10 | >10 | >10 |

| NZM09a,c | >10 | >10 | 8.33 |

| NZM40a,c | 4.44 ± 1.09 | 4.35 ± 1.31 | 3.01 ± 0.31 |

| HT29b | 0.263 ± 0.02 | 0.384 ± 0.07 | 0.601 ± 0.08 |

| SK-MEL-1b | 0.202 ± 0.07 | 0.448 ± 0.07 | 1.499 ± 0.04 |

| SK-MEL-28b | 0.075 ± 0.03 | 0.257 ± 0.11 | 0.381 ± 0.15 |

| A375b | 0.046 ± 0.02 | 0.101 ± 0.05 | 0.079 ± 0.02 |

| NZM20b,c | 0.002 ± 0.001 | 0.023 ± 0.004 | 0.024 ± 0.003 |

| NZM07b,c | 0.003 ± 0.001 | 0.024 ± 0.006 | 0.036 ± 0.008 |

The cells harbor B-RafWT.

The cells express B-Raf V600E.

Primary cell lines derived from New Zealand metastatic melanoma patients. The IC50 values were determined using MTTa,b or sulforhodamine Bc assay. Data are mean values ± standard deviation (SD) of three independent experiments.

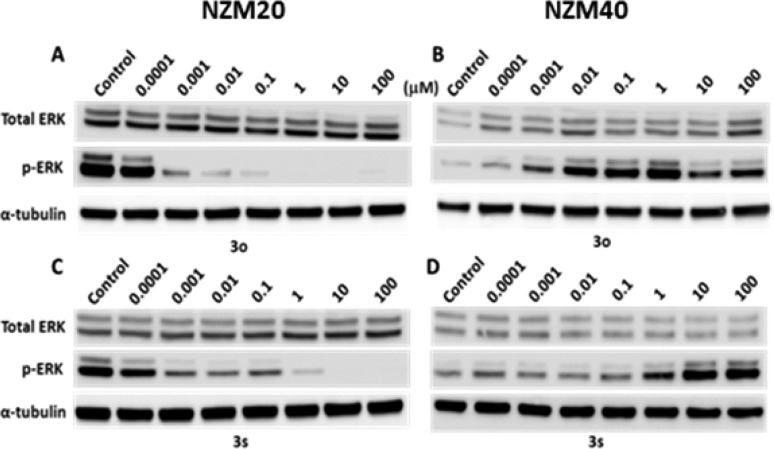

The B-Raf inhibition of 3o and 3s was further validated by investigating their suppressive abilities on the activation of MAPK signal pathway in NZM20 primary melanoma cancer cells expressing B-RafV600E and the corresponding NZM40 cells with B-RafWT (Figure 2). Both compounds displayed dose-dependent inhibition against the phosphorylation of ERK in NZM20 cancer cells by Western blot analysis. Alternately, an elevation of p-ERK level was observed for the compounds in NZM40 cells harboring B-RafWT and NRASN61H activating mutation, suggesting that inhibition of B-RafWT in this cell line may result in activation of a compensatory positive feedback loop, leading to increased ERK p44/p42 phosphorylation, as previously observed for vemurafenib, a phenomena that may be related to the appearance of benign skin lesions.19 The MAPK signal inhibition of the compounds was also validated in a pair of human colorectal cancer cells including B-RafV600E mutated Colo205 cells and HCT-116 cells with B-RafWT (Supporting Information).

Figure 2.

Compounds 3o and 3s dose-dependently inhibit the activation of ERK in NZM20 cells with B-RafV600E (A,C) but elevate the pERK levels in NZM40 harboring B-Raf WT (B,D).

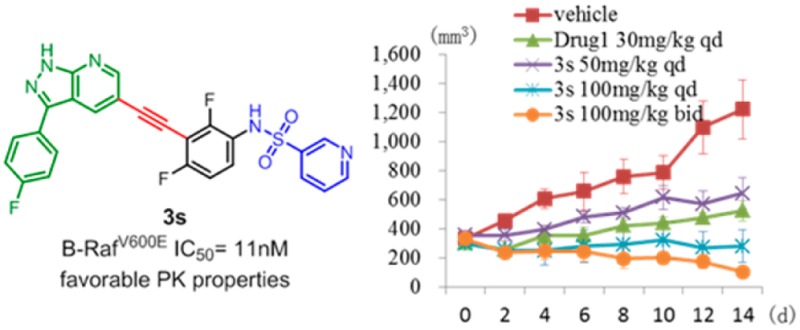

Compound 3s possesses favorable pharmacokinetic profiles with high oral exposures (AUC(0-∞) of over 30,000 μg/L·h and F% of 54.0% at a 25 mg/kg oral dose) and acceptable half-life (Supporting Information). It also displayed excellent target specificity in a kinase profiling investigation against 468 kinases with a selectivity score (S10) of 0.012 at 1.0 μM, which is about 48-fold of its Kd value against B-RafV600E (Supporting Information).20

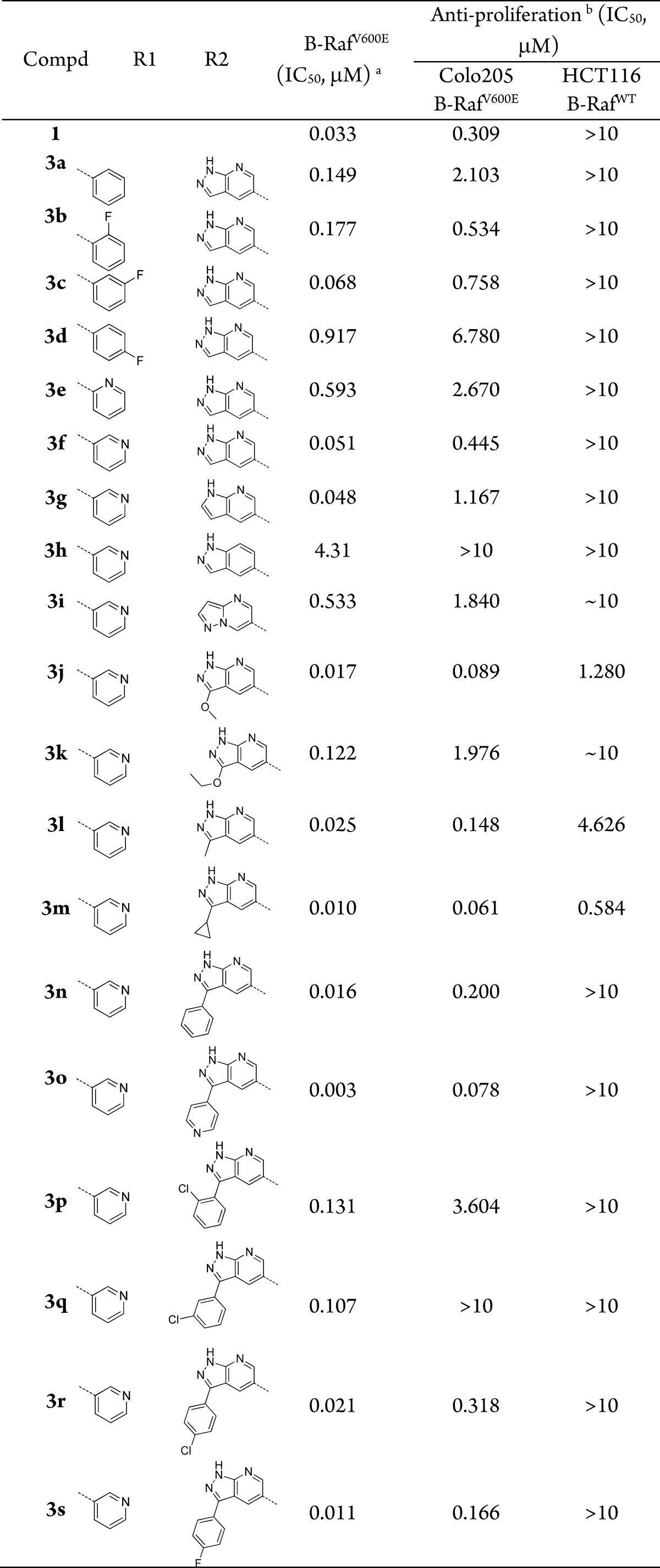

The in vivo antitumor efficacy of 3s was further evaluated using a xenograft mouse model of Colo205 cancer cells. The animals were repeatedly administrated with 3s once or twice daily via oral gavage for 14 consecutive days. Vemurafenib was used as a positive control (Figure 3). Compound 3s exhibited dose-dependent antitumor efficacy and was well tolerated in all of the tested groups with no mortality or significant loss of body weight (<5% relative to the vehicle-matched controls) observed during treatment (Supporting Information). The tumor growth inhibition (TGI) values are 47.3% and 77.1% at dosages of 50 and 100 mg/kg/day, respectively. More significantly, when the animals were treated with 100 mg/kg of 3s twice a day, 3 out of 6 mice achieved significant tumor regression, suggesting that sustained exposure of B-Raf inhibitor may be an efficient approach to treat B-RafV600E mutated human colorectal cancer.

Figure 3.

(A) Compound 3s dose-dependently inhibits the growth of Colo205 xenograft tumors following 14 consecutive days of administration. Days postinitial treatment (d; y-axis) is plotted against the corresponding tumor volume (mm3; x-axis). (B) Tumor volumes after the last administration of drugs: a, vehicle; b, vemurafenib (drug 1) 30 mg/kg qd; c, 3s 50 mg/kg qd; d, 3s 100 mg/kg qd; e, 3s 100 mg/kg bid.

In summary, a series of N-(3-ethynyl-2,4-difluorophenyl)sulfonamides were designed and synthesized as new selective B-Raf inhibitors. The compounds potently inhibit B-RafV600E kinase with low nanomolar IC50 values and selectively suppress the proliferation of a panel of human cancer cell lines with B-RafV600E mutation. One of the most promising compounds 3s demonstrates favorable pharmacokinetic properties and induces significant tumor regressions in a xenograft mouse model of B-RafV600E mutated Colo205 human colorectal cancer cells without significant sign of toxicity. This compound may serve as a new lead compound for further drug discovery targeting B-RafV600E mutation driven human cancers.

Supporting Information Available

Experimental procedures for the syntheses, 1H NMR and 13C NMR for final compounds, kinase selectivity, and details of in vitro and in vivo assays. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

We thank financial support from Ministry of Science and Technology of China (#2014DFG32100), the National Natural Science Foundation (#81425021, #21302186), and the Health Research Council of New Zealand (13/1020).

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Dhillon A. S.; Hagan S.; Rath O.; Kolch W. MAP kinase signalling pathways in cancer. Oncogene 2007, 26, 3279–3290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maurer G.; Tarkowski B.; Baccarini M. Raf kinases in cancer-roles and therapeutic opportunities. Oncogene. 2011, 30, 3477–3488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fransen K.; Klintenas M.; Osterstrom A.; Dimberg J.; Monstein H. J.; Soderkvist P. Mutation analysis of the BRAF, ARAF and RAF-1 genes in human colorectal adenocarcinomas. Carcinogenesis 2004, 25, 527–533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tiacci E.; Trifonov V.; Schiavoni G.; Holmes A.; Kern W.; Martelli M. P.; Pucciarini A.; Bigerna B.; Pacini R.; Wells V. A.; Sportoletti P.; Pettirossi V.; Mannucci R.; Elliott O.; Liso A.; Ambrosetti A.; Pulsoni A.; Forconi F.; Trentin L.; Semenzato G.; Inghirami G.; Capponi M.; Di Raimondo F.; Patti C.; Arcaini L.; Musto P.; Pileri S.; Haferlach C.; Schnittger S.; Pizzolo G.; Foa R.; Farinelli L.; Haferlach T.; Pasqualucci L.; Rabadan R.; Falini B. BRAF mutations in hairy-cell leukemia. N. Engl. J. Med. 2011, 364, 2305–2315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xing M. BRAF mutation in thyroid cancer. Endocr. Relat. Cancer 2005, 12, 245–262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wan P. T.; Garnett M. J.; Roe S. M.; Lee S.; Niculescu-Duvaz D.; Good V. M.; Jones C. M.; Marshall C. J.; Springer C. J.; Barford D.; Marais R. Cancer Genome, P. Mechanism of activation of the RAF-ERK signaling pathway by oncogenic mutations of B-RAF. Cell 2004, 116, 855–867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holderfield M.; Deuker M. M.; McCormick F.; McMahon M. Targeting RAF kinases for cancer therapy: BRAF-mutated melanoma and beyond. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2014, 14, 455–467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X.; Kim J. Conformation-specific effects of Raf kinase inhibitors. J. Med. Chem. 2012, 55, 7332–7341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turajlic S.; Ali Z.; Yousaf N.; Larkin J. Phase I/II RAF kinase inhibitors in cancer therapy. Expert Opin. Invest. Drugs 2013, 22, 739–749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bollag G.; Hirth P.; Tsai J.; Zhang J.; Ibrahim P. N.; Cho H.; Spevak W.; Zhang C.; Zhang Y.; Habets G.; Burton E. A.; Wong B.; Tsang G.; West B. L.; Powell B.; Shellooe R.; Marimuthu A.; Nguyen H.; Zhang K. Y.; Artis D. R.; Schlessinger J.; Su F.; Higgins B.; Iyer R.; D’Andrea K.; Koehler A.; Stumm M.; Lin P. S.; Lee R. J.; Grippo J.; Puzanov I.; Kim K. B.; Ribas A.; McArthur G. A.; Sosman J. A.; Chapman P. B.; Flaherty K. T.; Xu X.; Nathanson K. L.; Nolop K. Clinical efficacy of a RAF inhibitor needs broad target blockade in BRAF-mutant melanoma. Nature 2010, 467, 596–599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibney G. T.; Zager J. S. Clinical development of dabrafenib in BRAF mutant melanoma and other malignancies. Expert Opin. Drug Metab. Toxicol. 2013, 9, 893–899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hertzman Johansson C.; Egyhazi Brage S. BRAF inhibitors in cancer therapy. Pharmacol. Ther. 2014, 142, 176–182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lito P.; Rosen N.; Solit D. B. Tumor adaptation and resistance to RAF inhibitors. Nat. Med. 2013, 19, 1401–1409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kopetz S.; Desai J.; Chan E.; Hecht J. R.; O’Dwyer P. J.; Lee R. J.; Nolop K. B.; Saltz L. PLX4032 in metastatic colorectal cancer patients with mutant BRAF tumors. J. Clin. Oncol. 2010, 28, 15S. [Google Scholar]

- Dubbaka S. R.; Vogel P. Palladium-catalyzed desulfitative Sonogashira-Hagihara cross-couplings of arenesulfonyl chlorides and terminal alkynes. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2004, 346, 1793–1797. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng H.; Chang Y.; Zhang L.; Luo J.; Tu Z.; Lu X.; Zhang Q.; Lu J.; Ren X.; Ding K. Identification and optimization of new dual inhibitors of B-Raf and epidermal growth factor receptor kinases for overcoming resistance against vemurafenib. J. Med. Chem. 2014, 57, 2692–703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joseph E. W.; Pratilas C. A.; Poulikakos P. I.; Tadi M.; Wang W. Q.; Taylor B. S.; Halilovic E.; Persaud Y.; Xing F.; Viale A.; Tsai J.; Chapman P. B.; Bollag G.; Solit D. B.; Rosen N. The RAF inhibitor PLX4032 inhibits ERK signaling and tumor cell proliferation in a V600E BRAF-selective manner. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2010, 107, 14903–14908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stones C. J.; Kim J. E.; Joseph W. R.; Leung E.; Marshall E. S.; Finlay G. J.; Shelling A. N.; Baguley B. C. Comparison of responses of human melanoma cell lines to MEK and BRAF inhibitors. Front. Genet. 2013, 4, 66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Su F.; Viros A.; Milagre C.; Trunzer K.; Bollag G.; Spleiss O.; Reis J. S.; Kong X. J.; Koya R. C.; Flaherty K. T.; Chapman P. B.; Kim M. J.; Hayward R.; Martin M.; Yang H.; Wang Q. Q.; Hilton H.; Hang J. S.; Noe J.; Lambros M.; Geyer F.; Dhomen N.; Niculescu-Duvaz I.; Zambon A.; Niculescu-Duvaz D.; Preece N.; Robert L.; Otte N. J.; Mok S.; Kee D.; Ma Y.; Zhang C.; Habets G.; Burton E. A.; Wong B.; Nguyen H.; Kockx M.; Andries L.; Lestini B.; Nolop K. B.; Lee R. J.; Joe A. K.; Troy J. L.; Gonzalez R.; Hutson T. E.; Puzanov I.; Chmielowski B.; Springer C. J.; McArthur G. A.; Sosman J. A.; Lo R. S.; Ribas A.; Marais R. RAS Mutations in Cutaneous Squamous-Cell Carcinomas in Patients Treated with BRAF Inhibitors. N. Engl. J. Med. 2012, 366, 207–215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karaman M. W.; Herrgard S.; Treiber D. K.; Gallant P.; Atteridge C. E.; Campbell B. T.; Chan K. W.; Ciceri P.; Davis M. I.; Edeen P. T.; Faraoni R.; Floyd M.; Hunt J. P.; Lockhart D. J.; Milanov Z. V.; Morrison M. J.; Pallares G.; Patel H. K.; Pritchard S.; Wodicka L. M.; Zarrinkar P. P. A quantitative analysis of kinase inhibitor selectivity. Nat. Biotechnol. 2008, 26, 127–132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.