Abstract

Background

Surprisingly little is known about the use of modal auxiliaries by children with specific language impairment (SLI). These forms fall within the category of grammatical morphology, an area of morphosyntax that is purportedly very weak in children with SLI.

Aims

Three studies were conducted to examine the use of modal auxiliaries by preschool-aged children with SLI.

Methods & Procedures

In each of the three studies, probe tasks were designed to create contexts that encouraged the use of modals to express the modality functions of ability and permission. In Study 1 and Study 3, English-speaking children participated. In Study 2, the participants were Cantonese-speaking children. In each study, three groups of children participated: A group exhibiting SLI, a group of younger typically developing children (YTD), and a group of (older) typically developing children (OTD) matched with the SLI group according to age.

Outcome & Results

In Study 1, we found that English-speaking children with SLI were as proficient as YTD children though less proficient than OTD children in the use of the modal can to express the modality functions of ability and permission. In Study 2, the same modality functions were studied in the speech of SLI, YTD, and OTD groups who were speakers of Cantonese. In this language, tense is not employed, and therefore the modality function could be examined independent of formal tense. Results similar to those of Study 1 were obtained. In Study 3, we again studied SLI, YTD, and OTD groups in English, to determine whether the children’s expression of ability differed across past (could) and non-past (can) contexts. The results for can replicated the findings from Study 1. However, the children with SLI were significantly more limited than both the YTD and OTD groups in their use of could.

Conclusions

These results suggest that most children with SLI have access to modality functions such as ability and permission. However, the findings of Study 3 suggest that they may have a reduced inventory of modal forms or difficulty expressing the same function in both past and non-past contexts. These potential areas of difficulty suggest possible directions for intervention.

Introduction

Much of the morphosyntactic research on children with specific language impairment (SLI) has dealt with finite verb morphology. For example, it is well documented that children with SLI who speak Germanic languages have extraordinary difficulties with verb inflections and auxiliary verbs that mark tense. In German, Dutch, Swedish, as well as English, children with SLI use present and/or past tense verb forms significantly less consistently than typically developing compatriots who are two years their junior (e.g. Bartke 1994, de Jong 1999, Hansson and Leonard 2003, Leonard, Eyer, Bedore and Grela, 1997, Rice and Wexler 1996).

Although verb forms that mark tense have been the focus of much research on SLI, relatively few studies have examined these children’s use of finite verb forms that express modality. Surprisingly, this is true even for English, the language that has probably been the object of the most intensive research on the morphosyntactic abilities of children with SLI. The goal of the present study was to provide much-needed data on the expression of modality by children with SLI from two language groups, English and Cantonese. Following a description of modality in these two languages, we turn to the contributions that an examination of modality in English and Cantonese can make to the study of SLI.

Modality in English and Cantonese

Traditionally, modality is subdivided into epistemic modality (the qualification of a proposition based on factual knowledge, as in These must be Caroline’s keys), and deontic modality (the qualification of a proposition based on reference to norms, as in You must be quiet!). A more recently proposed modality is that of dynamic modality, which deals with personal ability to accomplish acts, as in She can lift that.

In English, modality is primarily conveyed through modal auxiliary verbs such as can, could, will, and must, among others. Certain modal verbs can serve several modality functions. For example, can is often used as an alternative to other modals to express ability (e.g. Dogs can swim), possibility (She could/can use the ladder to get up on the roof), and permission (You may/can go outside and play now) (Quirk and Greenbaum 1973, Bybee 1985). English modals are not inflected for person or number agreement with the subject. However, formal tense distinctions are made. In some instances, these distinctions correspond directly with events in time, as in can/could in I can run the mile in six minutes, but when I was younger I could run it in five minutes. However, the correspondence between formal tense and events in time is not straightforward, as we discuss below.

Several studies have been directed at English-speaking children’s early use of modal verbs. According to the work of Wells (1979), Kuczaj (1982), and Richards (1990), can seems to emerge earlier and is used more frequently than other modals, with the exception of its negative counterpart, can’t. The modal can is often used in interrogatives to request permission. In declaratives, can is used most frequently to express the notion of ability, though often this use falls somewhere on a continuum between ability and circumstantial possibility (Richards 1990). It appears that can is the first modal to be used by children to express these notions, and each of these notions is expressed by age 2;6 (Kuczaj 1982). Papafragou (1998) has suggested that notions such as ability and permission are acquired earlier than functions that reflect epistemic modality because they do not require children to reflect on their own mental states. Choi (1995) has noted that other factors can also influence acquisition order, including the consistency and salience of the sentence position of the modal form, and the degree to which the modal is used for a single modality function, or is instead multi-functional in nature.

Cantonese differs significantly from English in its typology. It is a strongly isolating tone language. Six contrastive tones are employed; these are applied to lexical forms and grammatical morphemes alike. Cantonese expresses modality through modal verbs. As in English, these appear immediately before the main verb of the sentence and carry no inflections for agreement.

Cantonese and English are similar in the range of notions expressed by modal auxiliary verbs. For example, Cantonese modals express possibility, ability, and permission, among others. However, the two languages differ somewhat in how they partition particular modal verbs with particular modality functions. For example, in Cantonese, the modal ho2ji3 is often used to express possibility and permission but is not used for ability; the modal sik1 is frequently used for the latter function (Matthews and Yip 1994). (Cantonese words are presented here using the notation system of the Linguistic Society of Hong Kong, 1994; numerals refer to tone values.) Although data on young Cantonese-speaking children’s acquisition of modal verbs are rather limited, the available evidence indicates that by age 2;3, several modal verbs have already emerged (Lee, Wong and Wong 1996). (See Guo 1995 for related data for Mandarin.)

Modality and SLI

There are at least two important reasons to study the use of modal verbs by children with SLI in these two languages. First, as noted earlier, relatively little is known about these children’s ability to express the kinds of semantic notions that are reflected in modal use. Like tense and aspect, modality involves notions that go beyond the here and now. For example, expressions of ability are typically based on past experience. Permission, on the other hand, often deals with future events. Leonard (1995) observed that English-speaking children with SLI used modal auxiliaries less frequently than same-age peers. However, the data were obtained from spontaneous speech samples, and obligatory contexts for modals could not be readily determined. In a more recent investigation by Leonard, Deevy, Miller, Charest, Kurtz and Rauf (2003), a group of English-speaking children with SLI used can in a smaller percentage of likely contexts (M = 77) than a group of age controls (M = 95). However, can was assessed only in the context of expressing ability. It is simply not known how children with SLI will fare in the use of other functions such as permission. This issue serves as the focus of Study 1 and Study 2.

A second important reason to study modal use by children with SLI is that, in English, modal verbs are assumed to carry tense (Radford 1997). Specifically, English modals make the formal distinction between past (e.g. could) and non-past (e.g. can). As noted earlier, tense represents an area of extraordinary weakness in children with SLI. Therefore, it seems important to determine whether difficulties with tense extend to modal verbs.

There are reasons to suspect that problems with tense will be less apparent for contexts that promote the use of modals. Unlike auxiliary be forms, modal auxiliaries convey notions such as ability and permission. Some authors have proposed that such notions reflect a distinct functional category, modality, that is separate from the functional category associated with tense (Ouhalla, 1991). Therefore, it seems possible that children can produce modals even if they are unspecified for tense.

Another reason for believing that modals might be expressed without specification for tense is that the mapping between tense and past/non-past time is not straightforward. For example, although ability in past time employs the past tense modal could (e.g. I could run the mile in five minutes when I was younger), the expression of possibility often employs the same modal form even when no reference is made to past time (I could run the mile in five minutes if I trained properly). This opens up the possibility that children might learn forms such as could as reflecting a particular modality (possibility) that is distinguishable from the modality of can (ability), with no analysis of their formal tense value.

The above scenario reveals the importance of attempting to separate the modality function of modals from their formal tense values. For example, children with SLI might be able to express an adequate range of modality functions when these functions require modals with the same tense value. On the other hand, these children might show difficulty expressing the same modality function when the tense value of the modal must change. Such findings have both theoretical and clinical importance. For example, they would suggest that formal tense may be problematic in modals, as in other morphemes discussed in the SLI literature (e.g., auxiliary be forms, past –ed), even though elements of the morphemes (their modality function) may not constitute an area of difficulty. In turn, clinicians probably cannot restrict their intervention efforts to helping the children express an adequate range of modality functions. They must also ensure that the children can express the same modality functions using modals with past and non-past tense values.

We can think of three ways to examine modal use in a manner that separates modality and formal tense to the greatest extent possible. The first, pursued in Study 1, is to examine children’s use of different modality functions (ability, permission) that can be expressed using the same modal (can) with the same tense value (non-past). The second, explored in Study 2, is to examine the use of modals by children with SLI when tense is clearly not involved. Cantonese does not mark tense. Notions of past time, for example, must be established by means other than by verb tense, such as by use of temporal adverbs. Therefore, unlike English modals, any difficulty that Cantonese-speaking children with SLI exhibit in the use of modals cannot be attributed to problems with tense. The third way is to examine children’s use of the same modality function (ability) in contexts that require either a modal with the formal tense value of past (could) or a modal with the formal tense value of non-past (can). This issue is the focus of Study 3. In all three studies, children with SLI are compared to a group of typically developing same-age peers and a group of typically developing children approximately two years younger.

Study 1: The Use of Can in Ability and Permission Contexts

In Study 1, we examine English-speaking children’s use of both the ability modality function and the permission modality function. We restricted the study to contexts that promote the use of the modal can, a morpheme that carries the formal tense feature of non-past.

Method

Participants

A total of 60 children participated in Study 1, 20 in each of three groups. Twenty children, 12 males and 8 females, were diagnosed as exhibiting SLI. These children ranged in age from 48 to 78 months (M = 61.75, SD = 9.67). All of these children scored more than 1.5 SD below the mean for their age on the Structured Photographic Expressive Language Test – II (SPELT-II) (Werner and Krescheck 1983), and on a composite measure of finite verb morphology use (Leonard, Miller and Gerber 1999).

All but one of the children in the SLI group scored above 85 on the Columbia Mental Maturity Scale (CMMS) (Burgemeister, Blum and Lorge 1972), a test of nonverbal intelligence. The remaining child scored 83. In addition, each child passed an oral motor screening and a hearing screening. No child showed any evidence of neurological impairment or a history of seizures. The children’s mean length of utterance (MLU) in words based on a 100-utterance spontaneous speech sample ranged from 3.44 to 5.08 (M = 4.18), SD = 0.40).

An additional group of 20 children were younger and exhibited typical development (hereafter, the YTD children). These children, 8 males and 12 females, ranged in age from 32 to 49 months (M = 40.90, SD = 6.11). All of these children scored within 1 SD of the mean for their age on an age-appropriate measure of language and nonverbal intelligence. For the children age 36 months and older, the language measure was the SPELT – Primary (SPELT-P); for those under age 36 months, the U.S. standardization of the Reynell Developmental Scales (RDLS) (Reynell and Gruber 1990) were employed. For children age 42 months and older, the nonverbal intelligence measure was the CMMS. The Leiter International Performance Scale – Revised (LIPS-R) (Roid and Miller 1997) was used for the younger children. In addition, each child in this group passed both an oral motor and a hearing screening. The MLU of each child in this group was within 0.2 words of the MLU of a child in the SLI group. MLUs for these children ranged from 3.48 to 5.02 (M = 4.17, SD = 0.35).

The remaining 20 children were older typically developing children (hereafter, the OTD children); each of the children in this group was within 2 months of age of a child in the SLI group. Their ages ranged from 49 to 80 months (M = 61.00, SD = 9.59). Thirteen of the children were males, and 7 were females. All children in this group passed an oral motor and hearing screening and scored within 1 SD of their age on both the SPELT-II and the CMMS. Not surprisingly, their MLUs were higher than those of the children with SLI, ranging from 4.32 to 7.52 (M = 5.27, SD = 0.73).

Materials and Procedure

The children’s use of can in ability and permission contexts was assessed in separate tasks, each with 10 items. The tasks were administered on separate days, in counterbalanced order. The ability can task involved 10 different enactments (corresponding to the 10 items) with toy characters and props. The experimenter told each child that ‘shows’ were to be presented and that the child and Ken (a doll) were to watch the shows with the experimenter. The child was also told that Ken refuses to wear his glasses, and due to his poor eyesight he often gets the story mixed up. In these instances, the child was told, the experimenter and child would need to help Ken.

For each item in the ability can task, a second experimenter set up the characters and props behind the curtain of a puppet show stage. Once the curtain was opened, this experimenter acted out the scenario. For example, for one item, a police officer walks onto the stage and hears a cat crying for help. The cat is in a tree. A ladder is lying on the ground next to the tree. Ken says ‘Oh, the police officer wants to help the kitty get down. But I don’t think he can get up that high to save the kitty. (turning to the child) What do you think?’ The target in this case was an utterance such as He can use the ladder or an equivalent. It can be noted that the experimenter who prompted the child’s response made use of the modal can in her description of the scene, though an appropriate response would require the child’s use of can in a sentence that differed from the one provided by the experimenter.

The permission can task also involved two experimenters with the child, as well as toy characters and props. The child was introduced to the character Theo who was assigned the role of temporary caregiver/babysitter for the remaining characters. For each item, a character (manipulated by one experimenter) declared the desire to perform an action (e.g. watch TV). Theo (manipulated by the second experimenter) responded by saying that the character first had to do a particular chore (e.g. make the bed). The character then did the chore, and said to Theo ‘Did it!’ The second experimenter then said to the child ‘Ok, now what can she do? She brushed her teeth….What do you think?’ A response such as She can watch TV was expected. Again it can be seen that the (second) experimenter made use of can in her prompt, though an appropriate response by the child required use of the modal in a sentence that differed from the one used by the experimenter.

Scoring

Each response was examined to determine whether it provided a context for a modal auxiliary. For the ability can task, productions such as He need(s) the ladder or He has a ladder were regarded as unscorable, as they do not require a modal. For contexts suitable for a modal, three methods of scoring were employed. In the first, we counted any type of modal verb that was reasonable in the context. This was a liberal method of scoring that credited the child with productions such as He can use the ladder, He could use the ladder, and He will use the ladder. The second method of scoring included all instances of could and can. The modal could in these contexts has a function similar to that of can but places as much emphasis on the notion of possibility as on ability. For this second method of scoring, productions containing will were treated as unscorable. The third method was limited to responses containing can; thus productions with could (as well as will) were regarded as unscorable. For all three scoring methods, a percentage of use was calculated for each child, based on the total number of productions of the allowable modal(s) as the numerator, and the total of such productions plus the total number of scorable productions lacking a modal as the denominator. The resulting figure was then multiplied by 100 to create a percentage.

For the permission can task, imperatives directed at the character (e.g. Go watch TV) were regarded as unscorable. Provisions were also made to score the permission items to allow any modal (scoring method one), only the modals may and can (method two), and only can (method three). As will be seen, the three methods yielded the same results for both tasks, as alternatives to can were rarely produced.

Results and Discussion

The three scoring methods yielded essentially identical results. This was due to the fact that can was the modal produced in the great majority of instances, for all groups. For the ability can task, two children in the SLI group produced a total of two instances of could. For the YTD group, three children produced a total of six instances of could. Six children in the OTD group produced could a total of 11 times. The modal will was produced even less frequently by the three groups. For the permission can task, the modal can was used exclusively by the children in the SLI and YTD groups. Only a single child in the OTD group used an alternative modal; this child produced may on four items, and can on the remaining items.

Given the comparable findings for the three scoring methods, we performed statistical analysis only on the data from the third method. The children’s use of can was examined through a mixed model analysis of variance (ANOVA) with participant group (SLI, YTD, OTD) as a between-subjects variable and modality function (ability, permission) as a within-subjects variable. Arc-sine transformations were performed on the percentage data. Significant main effects or interactions were followed by post-hoc Least Significant Difference (LSD) tests at the .05 level and computations of the effect size d. Following Cohen (1988), d values of 0.80 and higher were considered large effect sizes, and those between 0.50 and 0.79 were viewed as medium effect sizes. A summary of the results appears in Table 1 and Figure 1. A main effect for participant group was observed, F (2, 57) = 6.51, p = .003. LSD testing at the .05 level revealed that the OTD group (M = 98.75, SD = 4.63) produced can to a significantly greater extent than both the YTD group (M = 87.53, SD = 23.07, d = 0.81) and the SLI group (M = 88.40, SD = 21.62, d = 0.80). The latter two groups did not differ.

Table 1.

The children’s use of modal auxiliaries in Study 1 (English) and Study 2 (Cantonese) to express ability and permission.

| Modals scored |

SLI ability permission |

YTD ability permission |

OTD ability permission |

|---|---|---|---|

| can | 84.95 91.86 | 84.50 90.55 | 99.00 98.50 |

| (28.07) (12.09) | (25.48) (20.59) | (4.47) (4.89) | |

| sik1/ | |||

| ho2ji5 | 56.71 57.77 | 67.23 57.72 | 67.87 84.59 |

| (43.95) (39.05) | (39.80) (45.77) | (39.34) (27.74) |

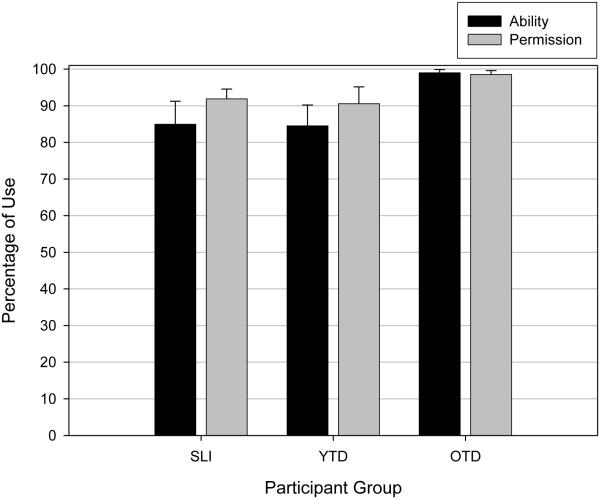

Figure 1.

Mean percentage of use (and standard error) for each participant group for ability can and permission can in Study 1.

Neither the main effect for modality function, F (1, 57) = 0.41, p = .52, nor the participant group by modality function, F (2, 57) = 0.27, p = .76, was significant. As can be seen in Figure 1, the percentages for permission showed a slight numerical advantage over the percentages for ability for the SLI and YTD groups, but these differences were not statistically reliable.

Perhaps the most salient feature of Figure 1 is the fact that the means for both modality functions were rather high for all three groups. However, there were individual children in both the SLI and YTD groups who performed at low levels on either the ability items or the permission items. One child with SLI showed 0% use of can in the ability context (though 100% in the permission context); another children from the same group used can in only 29% of possible ability contexts (and 90% use in permission contexts). The lowest percentage of use in permission contexts by a child with SLI was 60%. Among the YTD group, one child showed 0% use of can in the ability context (and 100% in permission contexts); another showed 50% use in ability contexts (100% in permission contexts). The lowest percentage seen in permission contexts for the YTD group was 70%.

With the exceptions noted above, the relatively high percentages by the children with SLI suggest that the ability and permission modality functions were not serious problems for these children, at least in contexts requiring the same non-past modal can. That is, although these children performed significantly below the level of the OTD group, they performed at the same level as the YTD children, in contrast to many studies of verb morphology that show a pattern of SLI < YTD. However, the seemingly identical performance of the SLI and YTD groups must be interpreted with caution. For example, the children with SLI may have been as capable as the YTD children in expressing modality, and did so without regard to formal tense. Alternatively, the SLI group might have possessed age-appropriate ability with modality but their difficulties with formal tense might have adversely affected their performance level, dropping it to the level of the YTD children. To evaluate these alternative possibilities, we turn to a language where modal use is independent of tense. In Study 2, we examine the use of modals by children who are acquiring Cantonese. This language does not employ tense, yet the modals of Cantonese express functions that overlap significantly with those found in English.

Study 2: The Use of Modals that Express Ability and Permission in Cantonese

In Cantonese, modals usually appear before the main verb, as in English. The morphemes serving as modals are not marked for tense and do not change as a function of the present or past nature of the event. Likewise, agreement is not employed in the language. In this study, we examined children’s use of two modals, sik1 and ho2ji5. The modal sik1 expresses ability, and is similar to can when used in contexts meaning ‘is able to’ or ‘knows how to’. The modal ho2ji5 is used in contexts pertaining to permission. Although Cantonese and English can convey essentially the same modality functions, Cantonese differs from English in how these functions are divided among the modals of the language. The modal ho2ji5, frequently used for permission, can be extended to the function of possibility. However, it does not convey the sense of ability, unlike English can which is applicable to ability as well as permission and possibility.

Method

Participants

Forty-five children residing in Hong Kong participated in Study 2. These children were participants in previous studies reported by the authors (Wong, Leonard, Fletcher and Stokes 2004, Fletcher, Leonard, Stokes and Wong 2005). Fifteen of the children met the criteria for SLI. Twelve of these children were males, three were female. These children ranged in age from 50 to 80 months (M = 60.67, SD = 7.60). All of these children had been diagnosed as exhibiting language problems at one of the local child assessment centers. Each child in this group scored more than 1.2 SD below the mean for their age on the Cantonese standardization of the Comprehension Scale of the Reynell Developmental Language Scales (RDLS) (Reynell and Huntley 1987). MLUs were also computed for these children. This measure serves to reliably distinguish children with SLI from typically developing same-age peers in Cantonese (Klee, Stokes, Wong, Fletcher and Gavin 2004). The children’s MLUs in words based on a 100-utterance sample of spontaneous speech ranged from 2.81 to 4.72 (M = 3.75, SD = 0.70). Fourteen of the 15 children scored above 85 on the CMMS. The remaining child scored 83. All children passed both an oral motor and a hearing screening. No child showed present or previous symptoms of neurological impairment.

The second group of 15 children were younger typically developing children, ranging in age from 35 to 42 months (M = 37.73, SD = 2.12). Three children were male, 12 were female. Hereafter, these children will be referred to as the YTD children. These children scored within 1 SD of the mean for their age on the Comprehension Scale of the RDLS and on either the CMMS or the LIPS (Leiter 1979). All passed a screening for oral motor and hearing ability. The YTD children’s MLUs ranged from 2.83 to 5.32. Although these children were not selected according to their MLUs, the mean (3.83) and distribution (SD = 0.63) of MLUs for this group were highly similar to those of the children with SLI.

The remaining 15 children were older typically developing (OTD) children. Eleven children were male, four were female. The children ranged in age from 49 to 81 months, and matched the children in the SLI group in both mean age (60.47) and distribution (SD = 7.76). These children’s scores on both the Comprehension Scale of the RDLS and on the CMMS were within 1 SD of the mean for their age. The children’s MLUs ranged from 3.57 to 6.20 (M = 4.49, SD = 0.77). They, too, passed a screening for oral motor ability and hearing.

Materials and Procedure

Two tasks were employed, one assessing the children’s use of the ability modality function, requiring the modal sik1, the other assessing their use of the permission function, requiring the modal ho2ji5. Both tasks involved two experimenters and the child, and drawings prepared specifically for this study.

For the ability sik1 task, the child was told that the first experimenter and the child were to serve as the teachers and the second experimenter would be the student. For each drawing, the first experimenter stated an action that the depicted character is not capable of doing, and then prompted the child to state what the character is capable of doing. The latter was clearly depicted in the drawing. An example is shown in (2), where the drawing depicted a fish swimming (CL = noun classifier).

(2) Exper 1: tiu4 jyu2 m4 sik1 haang4 lou6, daan6hai6…

CL fish not can walk road, but…

The fish can’t walk, but…

Child: tiu4 jyu2 sik1 jau4soei2

CL fish can swim

The fish can swim

It can be seen that, as in the ability can task used in Study 1, the experimenter’s prompt included the modal sik1 (preceded by the negative m4 ‘not’). However, the child was required to produce this modal in a sentence that involved a different main verb. Sixteen items were used in this task.

For the permission ho2ji5 task, the first experimenter told the child that the second experimenter was to play the role of the grandmother and the child was to play the role of the grandchild who needed to ask permission to do particular things. An example is shown in (3). In this example, SFP = sentence-final particle.

(3) Exper 1: nei5 hou2 tou5o6, nei5 soeng2 sik6 je5, gam2 nei5 zau6 man6 maa4maa4…

you very hungry, you want eat thing, then you then ask grandma…

You are hungry. You want to eat. You ask grandma…

Child: ngo5 ho2 m4 ho2ji5 sik6 je5 aa3?

I can not can eat thing SFP

Can I eat?

Three details are worthy of note in this example, and all other items. First, unlike in the previous task, the permission modal (ho2ji5) does not appear in the experimenter’s prompt. Second, sentences seeking permission usually involve a construction in Cantonese that is best translated literally as ‘can not can’ though the full form ho2ji5 is only produced once. Third, such requests serve as questions, but the word order matches declarative word order, with the modal ho2ji5 appearing after the subject and before the main verb. Sixteen items were used for this task.

Scoring

The children’s responses were examined to ensure that they contained appropriate contexts for the respective modals. For both tasks, two scoring methods were adopted. One method considered only the target modal (ability sik1, permission ho2ji5) as scorable and all other modals as unscorable. The other method allowed for alternative modals. In the permission task, the modal soeng2 was plausible. This modal (which actually appeared in the experimenter’s utterance) conveys volition in the sense of ‘wish’ or ‘want’. Another plausible response during the permission task was the modal jiu3, which conveys the function of necessity (‘need’). In the ability task, it was plausible that children could apply ho2ji5, thus altering the function to that of possibility. A more extreme alteration would take the form of the modal jiu3 to express not only possibility but necessity. As in Study 1, percentages of use were calculated for each scoring method, for each of the two tasks.

Results and Discussion

To facilitate comparison with Study 1, the first analysis employed the data derived from the scoring method in which only the target modals (ability sik1, permission ho2ji5) were treated as scorable. A mixed model ANOVA with participant group (SLI, YTD, OTD) and modality function (ability, permission) was performed, with arc-sine transformations of the percentage data. A summary of the findings is provided in Table 1 and Figure 2. There were no main effects for participant group, F (2, 40) = 1.70, p = .20, or modality function, F (2, 40) = 0.16, p = .69, and no participant group by modality function interaction, F (2, 40) = 0.92, p = .41.

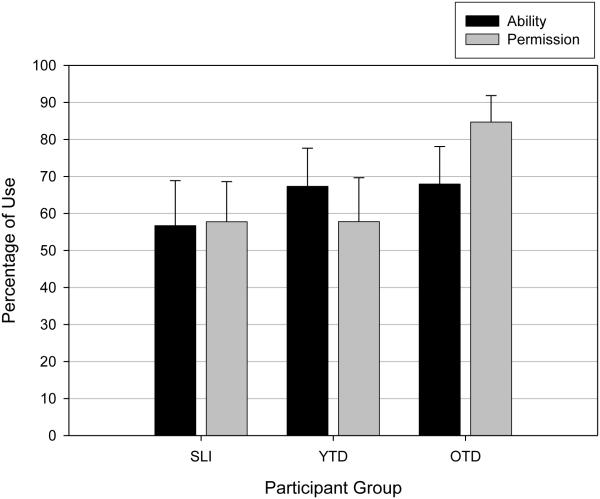

Figure 2.

Mean percentage of use (and standard error) for each participant group for ability sik1 and permission ho2ji5 in Study 2.

As can be seen from Figure 2, the mean percentages of use of the two modals were not especially high for any group. The permission modal ho2ji5 was used in 100% of possible contexts by eight of the children in the OTD group, but one child in this group showed 0% use and another showed 50% use of the same modal. For the ability modal sik1, fewer children in the OTD group scored at 100% (four children), and several scored at low levels, including two children scoring at 0% and 6%. When children failed to produce a modal, they produced a sentence that described the action (e.g. jyu2 jau4soei2 ‘The fish swim’) with no modality expressed.

The SLI and YTD groups were highly similar to each other in their use of both ho2ji5 and sik1. This was true not only in mean percentage of use but also in the extreme scores seen in each group for each type of modal. At least two children in each of these groups showed 0% use of both ho2ji5 and sik1, and each modal showed 100% use by at least three children in each group. Several other children in each group produced one or both modals with percentages between 90% and 100%. Again, failures to produce the modal took the form of otherwise appropriate descriptions of the action with no modality expressed. When the data were re-examined treating all modals as scorable, percentages of use were slightly higher but, again, the SLI and YTD groups were very similar in their modal use, showing no significant difference (p = .67).

The similar performance between the SLI and YTD groups for Cantonese – a language that does not employ tense – seems to reinforce the possibility that the English-speaking children with SLI in Study 1 were not adversely affected by the formal tense value of the modal can. That is, it seems unlikely that they were superior to the YTD children in their ability with modality functions but were hampered by the formal tense involved with English modals. If this were the case, we would have seen differences between the SLI and YTD groups favoring the former in the present study, as tense is not involved in Cantonese. In Study 3, we return to children’s use of modals in English, this time altering the context of past versus non-past while keeping the modality function the same.

Study 3: The Expression of Ability in Past (Could) and Non-Past (Can) Contexts

In the two previous studies, children with SLI performed at the level of YTD children when expression of modality required modals with the same tense value (Study 1) or no tense (Study 2). In Study 1, it was not possible to determine whether the children with SLI had no special problems with tense, or simply produced modals with no specification for tense. In Study 3, we conducted a study of English-speaking children’s use of modals to express the same function, ability, in both past and non-past contexts. These contexts require modal forms that differ in their formal tense value. If children with SLI express modality with no specification for tense, they should differ from YTD children in their use of modals across these two contexts.

Method

Participants

Twenty-seven children served as participants in Study 3, nine children in each of three groups. None of the children had participated in Study 1. One group of nine children had been diagnosed as exhibiting SLI. Six of these children were male, three were female. These children ranged in age from 49 to 79 months (M = 61.78, SD = 12.19). All of the children in this group scored more than 1.5 SD below the mean for their age on the SPELT-II and the finite verb morphology composite, but scored above 85 on the CMMS. Each child passed an oral motor and hearing screening and had no history of neurological impairment.

Another group of nine participants, three males and six females, were younger typically developing (YTD) children. These children ranged in age from 32 to 59 months (M = 42.33, SD = 10.20). All of these children scored within 1 SD of the mean for their age on the RLDS, and scored above 85 on the LIPS-R. Each passed an oral motor and hearing screening. These children’s MLUs were very similar to those of the children with SLI, ranging from 3.30 to 5.27 (M = 4.19, SD = 0.60).

The remaining nine participants were older typically developing (OTD) children resembling the children with SLI in age. These children ranged in age from 49 to 80 months (M = 60.87, SD = 10.92). Five of these children were male, four were female. Each of these children scored within 1 SD of the mean for their age on both the SPELT-II and the CMMS. All of the children passed an oral motor and hearing screening. The children’s MLUs ranged from 4.12 to 6.46 (M = 5.22, SD = 0.72).

Materials and procedure

The tasks for can and could tapped the ability modality function only. Ten items were created for can and for could, with the can task preceding the could task. The task for can matched the task used in Study 1 for ability can (e.g. He can climb the ladder), in which a puppet show theatre format was employed using toy characters and props.

The task for could also involved a puppet show stage with toy characters and props, and the doll Ken who refused to wear his glasses. One experimenter manipulated the characters and a second experimenter played the part of Ken. A key difference between the task for could and that used for can is that there was a completion of the enacted event prior to Ken’s misstatement of the facts. For example, in one item, Batman needs to save some people in distress and begins to look for Spiderman and his Batmobile. He finds both and the two action heroes depart. After this event, Ken says ‘Oh, Batman needed some help. He could find Spiderman but he couldn’t find his Batmobile. (turning to the child) What do you think?’ A response such as (No), he could find his Batmobile was expected. The props were left in place to assist the children’s recall of the events that actually transpired. It can be seen from this example that the experimenter’s prompt contained the negative modal couldn’t combined with the remaining words needed in the child’s response (e.g. find his Batmobile). In addition, this prompt contained the modal could in a preceding clause. Given the experimenter’s preceding utterance and the visible props, then, the processing loads placed on the children were kept to a minimum.

Scoring

As in Study 1, we anticipated using three scoring methods. However, no child showed any use of modals other than can and could. Furthermore, the only children who produced could during the present tense task also used can on this task and never produced a sentence without either can or could. Consequently, their scores remained at 100% regardless of the scoring method employed. For the past tense task, only two modal forms were produced by the children, either the correctly adopted could or the errant (present-for-past tense) can.

Results

A mixed-model ANOVA was performed with participant group (SLI, YTD, OTD) as a between-subjects factor and context (non-past can, past could) as a within-subjects factor. Arc-sine transformations were applied to the percentage data. A summary of the findings can be seen in Figure 3. A main effect for participant group was found, F (2, 24) = 11.52, p < .001. The children with SLI (M = 48.89, SD = 43.86) showed significantly lower percentages than both the YTD (M = 84.61, SD = 23.08, d = 1.07) and the OTD (M = 95.94, SD = 9.68, d = 1.76) groups. The YTD and OTD groups did not differ. A significant main effect for context was also observed, F (1, 24) = 4.74, p = .039, with significantly higher percentages seen for non-past can (M = 85.11, SD = 25.69) than for past could (M = 67.85, SD = 41.06, d = 0.73). However, these main effects are best interpreted through the significant participant group by context interaction that was also found, F (2, 24) = 4.31, p = .025. Post-hoc LSD testing at the .05 level indicated for the SLI group, use of non-past can (M = 73.67, SD = 35.17) was significantly greater than use of past could (M = 24.11, SD = 38.34, d = 1.89). However, for both the YTD (can M = 83.89, SD = 23.09; could M = 85.33, SD = 24.44) and OTD (can M = 97.77, SD = 6.67; could M = 94.11, SD = 12.13) groups, the two contexts did not differ. Comparison among the participant groups revealed that the OTD group showed significantly greater use of can than the SLI group (d = 1.15) but not the YTD group. The SLI and YTD two groups did not differ. For past could, the SLI group showed significantly less use than both the YTD group (d = 1.95) and the OTD (d = 2.77) group. The YTD and OTD groups did not differ.

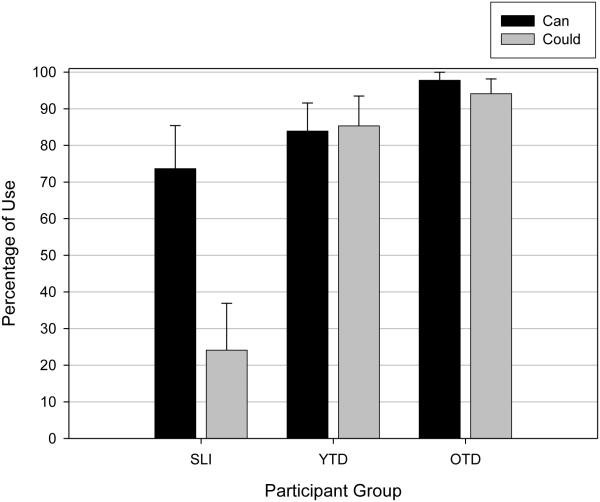

Figure 3.

Mean percentage of use (and standard error) for each participant group for non-past can and past could in Study 3.

One child in the SLI group failed to produce a modal in the non-past context. Four children in this group showed 100% use, and the remaining four showed intermediate degrees of use. For the past context, only three children in the SLI group produced could, with the remaining children showing 0% use. When the children with SLI failed to use could in the past context, approximately two-thirds of their responses were productions of can in place of could. Omissions of the modal constituted the remaining errors. Four children produced only can-for-could substitutions, one child always omitted the modal altogether. The remaining four children produced both substitutions and omissions. As can be seen from Figure 3, the YTD and OTD children had relatively little difficulty with the past context. However, for the five children in the YTD group and the two children in the OTD group who made errors, all errors were productions of can in place of could.

General Discussion

In Study 1, we found that English-speaking children with SLI were less proficient than OTD children in their use of the modal can to express ability and permission. However, these children did not differ from a group of YTD children. In Study 3, one of our measures was the use of can in ability contexts. The results for this modal and context replicated those of Study 1. Very similar findings emerged from Study 2, involving a comparison of Cantonese-speaking SLI, OTD, and YTD groups. The lone difference between children with SLI and YTD children came from the comparison in Study 3 of the children’s use of the modal could in past contexts. We organize the discussion of our findings around four themes. First, we consider factors that might complicate interpretation of the data, such as possible limitations in the method. We then discuss the children’s apparent ability in the expression of modality functions, and whether formal tense constituted a problem for these children. We conclude with a discussion of the clinical implications of the findings.

Potential Limitations

We noted in the method of each study that the experimenter’s prompt contained a modal verb that might have been used by the children (in a different sentence) to produce an appropriate response. Such prompts could well have led to elevated scores for the children. It should be noted, however, that the same task was used for all three participant groups in each study. Therefore, it is very doubtful that the group differences observed can be attributed to the appearance of the modal in these prompts. Indeed, it is more plausible to assume that the experimenter’s use of the modals in the prompts served to narrow the group differences. The OTD children could have been more proficient in the use of the modals and therefore benefited less from hearing the modals in the experimenter’s prompt. On the other hand, the children in the YTD and SLI groups may have had less experience with the modals and therefore their use of these morphemes might have been promoted by the experimenter’s prompts. It should be noted, however, that there were clear limits in the degree to which the prompts could have facilitated the children’s use of the modals. In Study 3, the children with SLI were significantly more limited than both the YTD and the OTD children in their use of the modal could in past contexts, in spite of the appearance of this modal in the experimenter’s prompt.

It can also be noted that the three groups in each study differed in the distribution of males and females. SLI is more prevalent in males. Furthermore, it is generally assumed that in the general population, girls outpace boys in their language development. The fact that our YTD groups had a larger percentage of girls than our SLI groups should have increased the likelihood of our replicating the well documented finding of YTD > SLI that is so prominent in the literature on verb morphology. Yet differences of this type were limited to ability could in past contexts in Study 3.

Given that Cantonese does not employ tense, percentages of modal use by children with SLI in this language might have been expected to be as high as, or higher than those seen for English. Yet, if anything, the percentages for Cantonese were somewhat lower. One possible reason for this finding is that, in Cantonese, otherwise-identical utterances without modals are fully grammatical. Recall that verbs are not marked for tense or agreement in Cantonese. Thus, an utterance such as He climb up the ladder in Cantonese may lack precision because it lacks a modality function, but it does not violate grammaticality. It is plausible that the grammatical acceptability of otherwise-identical utterances lowers children’s rate of including modals in their output.

Another possible explanation rests in the fact that English and Cantonese partition the modality functions somewhat differently. For example, in our task aimed at examining the ability function of can, appropriate responses such as He can climb up the ladder were taken as reflecting the child’s awareness of the character’s ability to use the ladder to rescue the cat in the tree. However, the response could also be taken as an observation of the possibility of rescuing the cat by climbing the ladder. In Cantonese, the modal for ability, sik1, is not used for the function of possibility. For this function, the same modal used for permission, ho2ji5, is required. Although natural languages obviously permit the possibility function to be expressed by a morpheme that is also used for ability and/or permission, it seems possible that the differences in form-function packaging across languages are associated with slightly different acquisition rates.

It might be argued that the absence of differences between the Cantonese-speaking children with SLI and the YTD and OTD children was due to our recruitment of children with SLI whose deficits were relatively mild. However, there are reasons to doubt such an assumption. Wong et al. (2004) and Fletcher et al. (2005) found that these same groups of children were not similar in their ability to use wh-questions and aspect markers, respectively. In the first of these studies, the children with SLI performed significantly below the level of both the YTD and OTD groups in producing wh-object questions (the Cantonese equivalent of ‘Who did the tiger push?’). In the second of these studies, the children with SLI were significantly less proficient than the YTD and OTD children in the use of aspect markers such as the continuous aspect marker gan2 (in both present and past time contexts) and the perfective aspect marker zo2. These findings suggest that the children with SLI were functioning well below age level – and even below the level of younger children with similar MLUs – on certain grammatical details. Therefore, the fact that group differences did not emerge for modal verbs seems noteworthy. Furthermore, given the percentages of use shown by the children (see Figure 2), the absence of group differences could not be attributed to ceiling or floor effects.

Expressing Ability and Permission in SLI

Based on our finding that a few individual children with SLI scored 0% on tasks that tapped one or another modality function, it seems that select children may have major difficulty with modality. On the other hand, given the statistical findings of Study 1 and Study 2 and the results for can in Study 3 (and the fact that these findings held true for the majority of children in the SLI groups), it is fair to conclude that the modality functions of ability and permission are not among the areas of serious weakness for most children with SLI. Although the children with SLI did perform below the level of typically developing same-age peers, differences of this type are ubiquitous in the literature. Of greater importance are findings in which the SLI group performs below the level of younger typically developing peers as well as same-age peers. Because several areas of morphosyntax do produce differences of this sort – thus reflecting more serious problems for children with SLI – it is useful to consider how modality functions such as ability and permission are similar, and different from these other, more problematic morphosyntactic notions.

Modality is often considered along with tense and aspect as one of the means of expressing temporal relations in the language (e.g. Aksu-Koc 1988). Certainly, some functions of modality clearly overlap with other notions of time, such as the expression of ‘futurity’ (Lyons 1968) through the modal verb will (e.g. I will leave at 9:00 a.m.). However, the functions of ability and permission are somewhat more removed from tense than futurity and similar notions.

It is also important to consider the types of modality that were examined in this investigation. Bybee (1985) refers to functions like ability and permission as ‘agent-oriented’ functions because they are about conditions that affect the state of affairs of the agent in the sentence. Other modality functions pertain to the speaker’s own views on the matter. The latter functions are generally acquired later by typically developing children. Papafragou (1998) has proposed that these other functions may be dependent on children’s theory of mind. It can be seen, then, that our finding of similar expression of ability and permission by children with SLI and YTD children should not be construed as a finding that all modality functions will produce similar results.

Problems with Tense?

At the outset of this paper, we noted that modal auxiliaries differ from other tense-related morphemes in that they serve modality functions such as ability and permission. Furthermore, the mapping between tense and past/non-past time is not straightforward for modals. For these reasons, it seemed possible that children with SLI might not differ from YTD children in their use of modals, even though, in the adult grammar, modals make the formal distinction between past tense and non-past tense. That is, it seemed possible that children with SLI might produce modals that are not specified for tense.

Most of the data were consistent with this possibility. In the use of ability can (Study 1, 3), permission can (Study 1), and their Cantonese counterparts (Study 2), the children with SLI were as capable as their YTD compatriots. Differences between children with SLI and YTD children were seen only in Study 3 in which the ability function had to be expressed in a clearly past context. Because the modality function of ability was employed in both the past and non-past contexts of Study 3, we felt that this study offered a means of separating the effects of tense from that of modality.

The finding of a large group difference between the SLI and YTD groups in the past context coupled with frequent use of can in place of could by the SLI group might certainly reflect problems with tense. However, these tense-related problems could have been manifested in one of two ways. First, the children with SLI might have appropriately adopted can to express the ability function, but, for these children, this modal might have had no specification for tense. A second possibility is that the children had an available modal form for non-past tense (can) but not for past tense. Recall that in Study 1, could was used only twice by children in the SLI group. Although the children in Study 1 and Study 3 were not the same, the sparse use of could in Study 1 suggests that this modal form might not have been in the inventories of some of the children with SLI in Study 3. Of course, the absence of this modal form might itself have been due to the children’s difficulty in recognizing its formal tense value.

Clinical Implications

The findings from Study 1 and 2 indicate that a minority of children with SLI might have special problems expressing modality functions such as ability even in contexts in which rather basic modals (e.g. can) can be used. The findings from Study 3 suggest that an even larger proportion of children with SLI seem to have special problems using modals across past and non-past contexts. This difficulty might be due to a tendency to express modality with no specification of tense, or to limited knowledge of modal forms with the proper formal tense value.

This pattern of findings suggests a three-step process for intervention aimed at assisting children in their acquisition and use of modals. First, clinicians might provide children with a modal form for each of the major modality functions served by modals in the child’s language. (It is possible, for example, that in Study 1 and 2, a few children simply had no knowledge that modals can express ability.) Second, activities might be provided that acquaint children with the multi-functional nature of certain modals. Otherwise, children might unduly restrict their use of particular modal forms (e.g. can only in permission contexts, could only in possibility contexts). Finally, children may need assistance in learning and using two different modal forms when the same modality function (e.g. ability) must be used in past as well as non-past contexts. Determination of the procedures most appropriate for these intervention goals must be discovered through future research. However, given the general success shown by the OTD children in the present investigation, the types of contexts employed here might be considered as a useful starting point.

Section 1: What is already known on this subject

It is already known that children with SLI have great difficulty with verb morphology. However, it is not known whether this problem extends to modal auxiliary verbs.

Section 2: What this study adds

The findings from this investigation indicate that select children with SLI may have a limited range of modality functions at their disposal, and a larger number may have difficulty expressing the same function in past as well as non-past contexts. These findings suggest a three-step process for intervention.

Acknowledgements

The research proposed in this article was supported by National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders Research Grant R01 00-458. We are grateful for the collaboration of the Child Language Program and the Preschool Language Program, Purdue University; the Hong Kong Christian Service, Choi Wan and Yeun Long Early Education and Training Centres; the Spastics Association of Hong Kong, Wang Tau Hom and Tak Tin Early Education and Training Centres; the Speech and Language Clinic at the Division of Speech and Hearing Sciences, University of Hong Kong; Pamela Youde Child Assessment Centre; and Yan Chai Hospital. We thank the children and families who participated. We are also grateful to Anna Lee, Barbara Brown, Eva Chau, Serena Chan, Diana Elam, Denise Finneran, Hope Gulker, Alice Lee, Cora Lee, Jeanette Leonard, Elgustus Polite, Lina Wong, and Richard Wong.

References

- Aksu-Koc A. The Acquisition of Aspect and Modality. Cambridge University Press; Cambridge, England: 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Bartke S. Dissociations in SLI children’s inflectional morphology: New evidence from agreement inflections and noun plurals in German; Paper presented at the Meeting of the European Group for Child Language Disorders; Garderen, The Netherlands. 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Burgemeister B, Blum L, Lorge I. Columbia Mental Maturity Scale. Harcourt Brace Jovanovich; New York: 1972. [Google Scholar]

- Bybee J. Morphology: A Study of the Relations Between Meaning and Form. John Benjamins; Amsterdam: 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Choi S. The development of epistemic sentence-ending modal forms and functions in Korean children. In: Bybee J, Fleischman S, editors. Modality in Grammar and Discourse. John Benjamins; Amsterdam: 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences. Lawrence Erlbaum; Hillsdale, NJ: 1988. [Google Scholar]

- de Jong J. Groningen Dissertations in Linguistics 28. The Netherlands; Groningen: 1999. Specific language impairment in Dutch: Inflectional morphology and argument structure. [Google Scholar]

- Fletcher P, Leonard L, Stokes S, Wong AM-Y. The expression of aspect in Cantonese-speaking children with specific language impairment. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research. 2005;48:621–634. doi: 10.1044/1092-4388(2005/043). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo J. The interactional basis of the Mandarin modal néng ‘can’. In: Bybee J, Fleischman S, editors. Modality in Grammar and Discourse. John Benjamins; Amsterdam: 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Hansson K, Leonard L. The use and productivity of verb morphology in specific language impairment: An examination of Swedish. Linguistics. 2003;41:351–379. [Google Scholar]

- Klee T, Stokes S, Wong AM-Y, Fletcher P, Gavin W. Utterance length and lexical diversity in Cantonese-speaking children with and without specific language impairment. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research. 2004;47:1396–1410. doi: 10.1044/1092-4388(2004/104). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuczaj S. Old and new forms, old and new meanings: The form-function hypothesis revisited. First Language. 1982;3:55–61. [Google Scholar]

- Lee TH-T, Wong CH, Wong CSP. Functional categories in child Cantonese. In: Lee TH-T, Wong CH, Leung S, Man P, Cheung A, Szeto K, Wong CSP, editors. The Development of Grammatical Competence in Cantonese-Speaking Children. University of Hong Kong; Hong Kong: 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Leiter R. Leiter International Performance Scale. Stoelting; Wood Dale, IL: 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Leonard L. Functional categories in the grammars of children with specific language impairment. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research. 1995;38:1270–1283. doi: 10.1044/jshr.3806.1270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leonard L, Deevy P, Miller C, Charest M, Kurtz R, Rauf L. The use of grammatical morphemes reflecting aspect and modality by children with specific language impairment. Journal of Child Language. 2003;30:769–795. doi: 10.1017/s0305000903005816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leonard L, Eyer J, Bedore L, Grela B. Three accounts of the grammatical morpheme difficulties of English-speaking children with specific language impairment. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research. 1997;40:1270–1283. doi: 10.1044/jslhr.4004.741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leonard L, Miller C, Gerber E. Grammatical morphology and the lexicon in children with specific language impairment. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research. 1999;42:1076–1085. doi: 10.1044/jslhr.4203.678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linguistic Society of Hong Kong . The LSHK Cantonese Romanization Scheme. Linguistic Society of Hong Kong; Hong Kong: 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Lyons J. Introduction to Theoretical Linguistics. Cambridge University Press; Cambridge, England: 1968. [Google Scholar]

- Matthews S, Yip V. Cantonese: A Comprehensive Grammar. Routledge; London: 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Ouhalla J. Functional Categories and Parametric Variation. Routledge; London: 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Papafragou A. The acquisition of modality: Implications for theories of semantic representation. Mind and Language. 1998;13:370–399. [Google Scholar]

- Quirk R, Greenbaum S. A Concise Grammar of Contemporary English. Harcourt Brace Jovanovich; New York: 1973. [Google Scholar]

- Radford A. Syntactic Theory and the Structure of English: A Minimalist Approach. Cambridge University Press; Cambridge, UK: 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Reynell J, Gruber C. Reynell Developmental Language Scales, U.S. Edition. Western Psychological Services; Los Angeles: 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Reynell J, Huntley M. Reynell Developmental Language Scales: Cantonese Version. NFER-Nelson; Windsor, England: 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Rice M, Wexler K. Toward tense as a clinical marker of specific language impairment in English-speaking children. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research. 1996;39:1239–1257. doi: 10.1044/jshr.3906.1239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richards B. Language Development and Language Differences: A Study of Auxiliary Verb Learning. Cambridge University Press; Cambridge, UK: 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Roid G, Miller L. Leiter International Performance Scale – Revised. Stoelting; Wood Dale, IL: 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Wells G. Learning and using the auxiliary verb in English. In: Lee V, editor. Language Development. Croom Helm; London: 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Werner E, Kresheck J. Structured Photographic Expressive Language Test – II. Janelle Publications; DeKalb, IL: 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Wong AM-Y, Leonard L, Fletcher P, Stokes S. Questions without movement: A study of Cantonese-speaking children with and without specific language impairment. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research. 2003;47:1440–1453. doi: 10.1044/1092-4388(2004/107). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]