Abstract

AIM: To screen for the co-infection of hepatitis B (HBV) and hepatitis C virus (HCV) in human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infected patients in southern India.

METHODS: Five hundred consecutive HIV infected patients were screened for Hepatitis B Virus (HBsAg and HBV-DNA) and Hepatitis C virus (anti-HCV and HCV-RNA) using commercially available ELISA kits; HBsAg, HBeAg/anti-HBe (Biorad laboratories, USA) and anti-HCV (Murex Diagnostics, UK). The HBV-DNA PCR was performed to detect the surface antigen region (pre S-S). HCV-RNA was detected by RT-PCR for the detection of the constant 5' putative non-coding region of HCV.

RESULTS: HBV co-infection was detected in 45/500 (9%) patients and HCV co-infection in 11/500 (2.2%) subjects. Among the 45 co-infected patients only 40 patients could be studied, where the detection rates of HBe was 55% (22/40), antiHBe was 45% (18/40) and HBV-DNA was 56% (23/40). Among 11 HCV co-infected subjects, 6 (54.5%) were anti-HCV and HCV RNA positive, while 3 (27.2%) were positive for anti-HCV alone and 2 (18%) were positive for HCV RNA alone.

CONCLUSION: Since the principal routes for HIV transmission are similar to that followed by the hepatotropic viruses, as a consequence, infections with HBV and HCV are expected in HIV infected patients. Therefore, it would be advisable to screen for these viruses in all the HIV infected individuals and their sexual partners at the earliest.

Keywords: Hepatitis B virus, Hepatitis C virus, Human immunodeficiency virus, Co-infection, Hepatotrophic viruses, HBV and HCV India, HBV and HCV and HIV

INTRODUCTION

Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and Hepatitis B and C viruses (HBV and HCV) are the three most common chronic viral infections documented world-wide[1,2]. These viruses have similar routes of transmission, namely through blood and blood products, sharing of needles to inject drugs and sexual activity, enabling co-infection with these viruses a common event[3-5]. HBV and HCV co-infections in HIV positive individuals is of utmost importance due to the underlying consequences such as the hepatological problems associated with these viruses, which have been shown to decrease the life expectancy in the HIV-infected patients[5].

Given the epidemiological similarities of HBV and HIV infections, it is not surprising that markers of past HBV infections namely hepatitis B surface antibody (anti-HBs) or hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) positivity, as the reported evidence of past HBV infection among people living with AIDS is about 10%[6,7]. HIV accounts for 38.6 million infections world-wide at the end of 2005[8] while HBV and HCV account for 400 million and 170 million chronic infections respectively[9,10]. Moreover, among the HIV-infected patients, 2-4 million are estimated to have chronic HBV co-infection while 4-5 million are co-infected with HCV[9]. Hepatitis B is a significant public health hazard in the subcontinent, where the average carrier rates in the general population is estimated to be 4%[11,12]. Further, reports on the prevalence of HCV infection in the Indian subcontinent are scarce. A community-based Indian study indicated a seroprevalence of 0.87%[13] and that the rate reportedly increased from 0.31% for children < 10 years to 1.85% among subjects > 60 years of age[13]. In addition, the rate of HBV and/or HCV co-infection in HIV patients have been variably reported depending on the geographic regions, risk groups and the type of exposure involved[14-20]. The literature regarding the prevalence of HIV co-infection with HBV and/or HCV in India is sparse. Hence, we investigated the co-infection pattern of HBV and HCV among HIV infected south Indian subjects with various risk factors and analyzed the association of viral markers of HBV and HCV infection among subjects with various stages of HIV disease.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study population

Patients attending clinics at YRG Centre for AIDS Research and Education (YRG CARE) were screened for HIV based on suspicion on clinical grounds after performing pre-test counseling and informed consent. Only the confirmed HIV positive serum samples (as per World Health Organization testing strategies) were included in this study and were anonymously tested for hepatitis B and C virus markers.

Virological assays

The patients were screened for HBV and HCV using ELISA kits; Hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg), Hepatitis B envelop antigen (HBeAg), antibody to envelop antigen (anti-HBe) using Biorad laboratories, USA and antibody to hepatitis C virus (anti-HCV) using Murex Diagnostics, UK. The HBV-DNA PCR was performed as per the methods of Shih et al[21]. Primers specific for the surface antigen region (pre S-S) were used for the molecular diagnosis of HBV infection. For the diagnosis of HCV RNA, extracted RNA was subjected to reverse transcriptase-nested polymerase chain reaction assays (RT-PCR) for the constant HCV 5' untranslated region (5'UTR)[22].

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics are presented with mean ± standard deviation (SD) or proportions, for continuous or categorical variables, respectively. The Mann-Whitney test was used to compare continuous variables between groups. Statistical package for social sciences (SPSS, Version 13.0) software was used for analyzing the data. A P value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Epidemiological characteristics

Of the 500 HIV infected participants investigated, 56 (11.1%) were co-infected with hepatitis viruses [45 (9%) HBV and 11 (2.2%) HCV positive]. Male gender predominance was observed (86%), (48 males and 8 females) and the median age was 37 years (95% CI ± 3.6) (range from 20-55 years). The main clinical, virological and epidemiological characteristics are presented in Table 1. Data on the risk factors for HIV seroconversion were available for all patients; 359 (72%) were heterosexual, 38 (8%) were intra venous drug users (IVDs), 46 (9%) were blood transfusion recipients and 57 (11%) were unnoticed. Among the co-infected patients the predominant risk factor observed was heterosexual (70%) rather than parental risk (14%) as shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of HIV and hepatitis coinfected patients

| Groups | Total | Age |

Sex |

Probable route of transmission |

Mean CD4 counts (cells/mm3) |

CDC status |

||||||

| Male | Female | Sexual | IVDs | Blood | Not known | A | B | C | ||||

| HIV alone | 444 | 36 ± 9 | 298 | 146 | 320 | 35 | 41 | 48 | ||||

| 334 ± 1991 | 261 | 171 | 201 | |||||||||

| HIV + HBV | 45 | 32 ± 6 | 39 | 6 | 35 | - | 2 | 8 | 294 ± 1732 | |||

| 42 | 192 | 172 | ||||||||||

| HIV + HCV | 11 | 38 ± 8 | 9 | 2 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 231 ± 104 | 1 | 3 | 7 |

CDC: Centre for Disease Control; IVD: Intra-venous drug users.

Based on the available clinical data, only 63 out of the total 444 HIV alone infected patients could be classified and

only 40 out of the total 45 HIV/HBV coinfected could be classified.

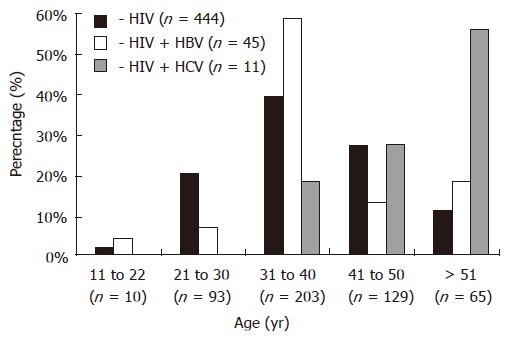

Majority of the HIV-infected patients were from the 31-40 years age group (39 %) followed by the 41-50 years age group (27%). Mean age of the HIV positive patients was 35 years (95% CI ± 6.8 years), 37 years (95% CI ± 3.6 years) among the co-infected patients. HBV-HIV co-infection was high in the 31-40 years age group (58%) while HCV-HIV co-infection was predominant among subjects with > 51 years of age (55%) (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Age-related distribution of HBV and HCV co-infection in HIV infected patients.

Immunological characteristics

The stage of HIV infection according to the revised 1993 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) classification was determined in all patients. Among 45 HIV/HBV co-infected patients only 40 patients were classified according to HIV disease groups namely Group A 4 (10%), Group-B 19 (48%) and Group-C 17 (42%) whereas all the 11 HIV/HCV co-infected subjects could be classified as Group-A, 1 (9%), Group-B, 3 (27%) and Group-C, 7 (64%). Nonetheless, the CD4 lymphocyte profile between HIV and hepatotropic virus co-infected patients was not significant (Table 1, Table 2, Table 3).

Table 2.

HBV marker profile of HBV/HIV co-infected patients (n = 40)

| HIV/HBV coinfection group (CDC 1993 revised) (n = 40)1 |

HBV marker |

|||

| HBsAg | HBeAg | Anti-HBe | HBV DNA | |

| Group A | 4 (10%) | 1 (25%) | 3 (75%) | 1 (25%) |

| Group B | 19 (48%) | 9 (47%) | 10 (53%) | 9 (47%) |

| Group C | 17 (42%) | 12 (71%) | 5 (29%) | 13 (76%) |

Based on the available clinical data, only 40 out of the total 45 HIV/HBV co-infected could be classified according to HIV disease group as per CDC-1993 revised classification.

Table 3.

HCV marker profile of HCV/HIV co-infected patients (n = 11)

| HIV Disease Group of HIV/HCV coinfected cases (CDC 1993 revised) | HCV coinfection (n = 11) | Anti- HCV and HCV RNA positive (n = 6) | Anti HCV alone positive (n = 3) | HCV RNA alone positive (n = 2) |

| Group A | 1 (9%) | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Group B | 3 (27%) | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Group C | 7 (64%) | 4 | 2 | 1 |

HBV and HIV co-infection

Of the 45 HIV/HBV co-infected patients, only 40 could be classified under the various HIV disease groups. The HBeAg positivity was seen in 25%, 47% and 71% whereas antiHBe positivity was seen in 75%, 53% and 29% in the HIV disease groups A, B, and C respectively (Table 2). The HBV DNA positivity was seen in 25%, 47% and 76% of the patients in groups A, B and C respectively (Table 2). The HBe/antiHBe was inversely proportional to each other and significantly associated with the stage of HIV disease progression (P < 0.01). Out of 23 total HBV-DNA positive cases, significantly higher level of HBV-DNA positivity (87%) was observed in HBe positive cases compared to HBe seroconverted patients (13%). In the overall HBV-DNA positivity among HIV/HBV co-infected patients, the stage of HIV disease progression was significantly associated the positivity pattern of HBV DNA (P < 0.01). Randomly selected 250 HBsAg seronegative cases were also tested for qualitative HBV-DNA by PCR and none of the patients revealed “occult” HBV infection.

HCV and HIV co-infection

Of the 11 HIV/HCV coinfected patients (i.e. either positive for anti-HCV or HCV RNA or both) (Table 1), 6 were anti-HCV and HCV RNA positive, 3 were anti-HCV alone positive and 2 were HCV RNA alone positive. The HCV-RNA positivity was 100%, 66%, and 71% in group-A, group-B, and group-C respectively (Table 3). From the remaining 489 anti-HCV seronegative cases, 300 were randomly selected for qualitative HCV-RNA testing by PCR, in which only 2 cases (0.6%) were positive for HCV-RNA, the CD4 counts were 58 and 205 cells per mm3 respectively. The RNA positivity in anti-HCV positive cases was highly significant (73% vs 0.6%) than the anti-HCV seronegative cases (P < 0.001).

DISCUSSION

India has the second highest number of people living with HIV[23]. Moreover, among the HIV infected patients, 2-4 million are estimated to have chronic HBV co-infection while 4-5 million are co-infected with HCV[9]. Co-infection of HBV and/or HCV with HIV complicates the clinical course, management and may also adversely affect therapy for HIV infection. The reported co-infection rates of HBV and HCV in HIV patients have been variable worldwide depending on the geographic regions, risk groups and the type of exposure involved[24-26]. Within India HBV and HCV co-infection among HIV infected patients have been reported infrequently from region to region[15-20]. However, our study indicated that HIV-infected patients are at a high-risk of viral co-infections, as evident from the high prevalence of HBV (9%) and HCV (2.2%), which is fairly higher than the HBV and HCV prevalence reported in the Indian general population[11,12].

Our findings showed that study group predominantly comprised of heterosexually acquired HIV infections than other mode of transmission and the male gender were significantly (86% vs 14%) higher than female (P < 0.01). This concords previous report that male subjects were significantly at a higher risk to develop HBV co-infection[14,18], justified by the age group against the pattern of co-infection analyzed in the present investigation. This data shows that the maximum levels (58%) of co-infection for HBV/HIV occurred in the 31-40 age-group, which is the normal age group where the HIV positivity is reportedly higher as per Indian literatures[15-20]. This also suggests that sexual route could also be the common mode of transmission for both HBV and HIV. Further, the chronic HCV co-infection rate in our study is in line with Padmapriyadarsini et al, from South India[18]. In contrast to the HIV/HBV co-infection observed among the sexually active age group viz. (31-40 years), the HIV/HCV co-infection was higher (55%) among the > 50 years age group, which speculates that HCV transmission could have been non-sexual and/or parenteral.

The frequency of anti-HCV among our HIV subjects (2.2%) is much lower than that reported previously amongst HIV/HCV co-infected Indian subjects[15-20] and much higher than from the general Indian community[12]. The low frequency of HCV could be due to the low incidence of IVD use and infrequent transfusion in our study groups, which are relatively different from that reported from other parts of India where IVDs and transfusion history were the main risk factors identified for HCV infection among HIV patients[15-20]. In our cohort, two individuals co-infected with HIV/HCV neither had transfusion history, IVDs use, tattooing, piercing nor sexual promiscuity with IVDs users; nevertheless presented details of high risk sexual behaviors and prior STI history, which suggests that sexual intercourse could have been the route of infection. In additional, both subjects had active HCV infection (positive HCV-RNA) but failed to seroconvert to anti-HCV. The CD4 T-cell counts (58 and 205 cells per mm3) are suggestive of HCV detection by ELISA among patients with very low CD4 counts may not be useful for screening. In agreement with earlier reports our study propose that prior HIV infection facilitates HCV transmission much easier, though this mode is not widely documented through sexual contact, which however needs more studies with more number of cohorts under the various risk groups and matched controls.

Co-infection of hepatotropic viruses in HIV disease reportedly leads to massive impairment of cell mediated responses and enhances the kinetics of hepatotropic viral replication[27-30]. Furthermore, HBV co-infection in HIV disease considerably complicates its diagnosis and management. Patients with AIDS apparently are less likely to clear HBV infection after exposure or more likely to reactivate latent HBV infection or both[30,31]. Our study showed that co-infection with HBV or HCV is frequent in HIV disease, as evident from higher HBV-DNA and HCV-RNA positivity rates. The effects of HIV on the course of chronic HBV and HCV infection have largely been assessed[1-5]. Our investigations are also suggestive of a higher degree of immunodeficiency, (CDC 1993 revised classification of HIV disease group (group A, B and C) concurrently with a higher rate of HBV and/or HCV replication and HIV disease progression. HBsAg-negative “occult HBV’ was not seen in our HIV population. Further, the HBeAg and anti-HBe positivity pattern of our study cohort clearly shows that, both the HBe and anti-HBe status were inversely proportional to HIV disease progression among the HIV/HBV co-infected cases. Statistically there is a significant trend between HBsAg positivity and HBV DNA positivity between the three CDC defined HIV disease groups (P < 0.01).

We observed that the incidence of HBV co-infection rises with disease progression. Significant difference of co-infection existed between the symptomatic and asymptomatic groups of HIV infected patients (P < 0.01). The co-infection seems to have pronounced effect on the natural history of these infections. Although the effect of HBV infection on HIV is uncertain, HIV appears to have marked influence on the natural history of HBV infection. The increased viral replication of HBV in AIDS patients indicates that HIV significantly affects the HBV life cycle and the host ability to clear HBV infection. If this holds true, more HBV infection and more chronic carriers would be expected as the AIDS epidemic expands in this part of the country. Such a profile would have worrisome public health implications since more chronic liver diseases, including HCC, would be expected as the mortality rate associated with HIV is reduced[32]. Chronic HBV infection can be associated with severe liver damage in HIV positive drug abusers and homosexuals. HIV infection does not seem to attenuate and may even worsen HBV associated chronic liver damage[30,33]. The long-term effect of immunodeficiency on the out come of hepatitis B infection remains to be evaluated. The HIV-RNA viral load difference was however not significant in our study groups. In regard to CD4 and CD8 counts, the HIV/HCV co-infected patients revealed a comparatively lower levels in the above parameters with the HIV and HIV/HBV co-infected patients, albeit statistically insignificant (data not shown). This could probably be due to small number of cases, wide range of CD4, CD8 counts and the HIV cases being in different stages of HIV disease. In the HIV/HCV co-infected groups, the HCV-RNA positivity was found to be higher in Group-C (71%) than group B (66%) but only one patient in group A showed HCV-RNA positivity. These observations are also concordant to previous reports of increased hepatotropic viral replication in immunocompromised subjects[34,35]. However, this needs to be confirmed with adequate number of patients with different stages of HIV disease.

The present study has certain limitations. Firstly, this is a cross-sectional study unable to adequately establish a casual relationship between the time of exposure and subsequent infection. Secondly, the study was conducted with patients limited to a tertiary HIV referral hospital setting and not of a community setting. However the results can be implied to approximate and prepare for clinical care of our HIV-infected patients. Moreover, at the time of this study, HIV negative group was not available. In addition, the HCV-RNA testing used to screen HCV infection in terms of cost was quite prohibitive in our resources-limited setting. Immunosuppression from HIV infection may impair antibody formation, and false-negative HCV antibody tests have been reported in individuals co-infected with HIV[36,37]. It is unlikely that the low seroprevalence of HIV/HCV co-infection was due to selection bias because subjects in the present investigation were selected from one tertiary referral hospital that covers a wide range of socio economic strata.

Uncertainties remain regarding the real effect of co-infection with HIV and HBV and HCV on the progression and outcomes of theses viral infections. The situation is largely due to difficulties in performing accurate natural history studies, particularly in the constantly developing field of HIV medicine. However, an increased infectivity for chronic HBV infections in HIV positive persons regardless of their clinical state or laboratory evidence of immune suppression that may have implications for hepatitis policies, and epidemiologic studies should be considered to monitor a possible increase in the spread of HBV among population at risk for HIV and HBV. Prolonged survival of HIV infected patients co-infected with HBV or HCV may become an important clinical problem. Our findings strengthen the evidence for the significance of HIV infection on the natural history of chronic HBV infection, which by prolonging the period of infectivity could have influenced the epidemiology of HBV infection in India[30,31]. It is thus far clear that apart from other infections, HIV infected individuals have a high probability of getting co-infected with HBV and/or HCV. HIV disease progression and enhanced immunosupression has a direct bearing on the natural history and pathogenesis of these infections. Sexual transmission of both HBV and HCV also appears to be significant and is of epidemiological importance in the light of high heterosexual transmission of HIV in India. Monitoring of HIV infected patients for concurrent infection with HBV and HCV is therefore necessary.

The implication of HBV and/or HCV co-infection in HIV patients is of serious concern to the growing Indian economy as there is an overt increase in the trend of number of patients diagnosed with HIV disease in recent years. The knowledge of co-infection in a HIV positive patient is vital since these patients, as they live longer on antiretroviral treatment will also need to be managed for their co-infection with HBV and/or HCV. Hence, there is an urgent need to conduct, detailed studies on the interplay of HIV and hepatotropic viruses in the Indian community with a plethora of multifaceted approaches to investigate the real crisis of HIV/hepatotropic viral infection pattern at the earliest to efficiently control and manage the situation.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We highly appreciate the cooperation and assistance received from all clinicians, paramedical and nursing colleagues of YR Gaitonde Centre for AIDS Research and Education (YRG CARE), Chennai, India and the patients who participated in the study.

COMMENTS

Background

The influence of HBV or HCV co-infections among subjects with HIV disease is of serious concern to the development of the Indian economy as an increase in the overall trend in the number of patients diagnosed with HIV disease is raising in the recent years. Therefore, scientific knowledge of hepatotropic co-infections in the HIV/AIDS community is important, as they live longer after prompt antiretroviral treatment, in addition to concurrent effective management of HBV or HCV co-infections. Hence, there arises an urgent need to carry out elaborate studies on the interplay of HIV and hepatotropic viruses in the community with a multifaceted approach to promptly explore the scientific facts behind the real crisis to efficiently control and manage the circumstances.

Research frontiers

Uncertainties remain regarding the real effect of co-infection with HIV and HBV or HCV on the progression and outcome of these infections due to the foreseeable difficulties in performing accurate natural history studies, particularly in the persistently developing field of HIV medicine. Although the effect of HBV infection on HIV is indecisive, HIV appears to have a marked role on the natural history of HBV infection in concordant to earlier reports. Therefore, we propose that HIV influences the natural history of HBV and/or HCV replication, which may have implications for development of hepatitis policy guidelines and epidemiologic studies need to be aimed at strengthening approaches to monitor the possible increase in the spread of HBV and HCV among population at risk for HIV.

Innovations and breakthroughs

The low frequency of HCV in our cohort could be attributed to the low incidence of intravenous drug usage and the infrequent incidence of transfusion, which are substantially different to other reports from parts of India, where IDU and prior transfusion history are reportedly the main risk factors identified among HCV/HIV co-infection. On the contrary, two individuals co-infected with HIV/HCV never had the aforementioned predominant risks; nevertheless presented details of high risk sexual behaviors and prior STI history, which suggestive of the fact that sexual intercourse could also have been the route infection. In additional, both subjects had active HCV infection (evident from positive HCV-RNA) but failed to seroconvert to anti-HCV. The CD4 T-cell counts (58 and 205 cells per mm3) were suggestive of anti-HCV detection with very low CD4 counts and may not be useful for screening. In line with earlier reports, we propose that prior HIV infection could facilitate HCV transmission much easier, though this has not been widely described, and needs more prospective investigations with more number of cohorts with matched controls in the context of HIV/AIDS.

Applications

Though there are few available data on the prevalence of these infections in the Indian general population, information in the HIV positive community is inadequate. In view of the major mode of HIV spread in India being heterosexual, and parenteral route accounting for < 5% of the infections, screening the high-risk population for these infections would aid early detection of co-infections. Hence, initiation of prompt diagnosis and treatment would help decrease the further spread of these chronic viral infections.

Terminology

Hepatitis ‘e’ antigen (HBeAg) is a peptide and normally detectable in the bloodstream when the hepatitis B virus is actively reproducing, this in turn leads to the person being much more infectious and at a greater risk of progression to liver disease; however, some variants (precore mutant) of the hepatitis B virus do not produce the ‘e’ antigen at all, so this rule does not always hold true; Anti-HBe is an antibody produced in response to the Hepatitis B e antigen. In those who have recovered from acute hepatitis B infection, anti-HBe will be present along with anti-HBc and anti-HBs. In those with chronic hepatitis B, usually anti-HBe becomes positive when the virus goes into hiding or is eliminated from the body and this phase is generally taken to be a good sign and indicates a favourable prognosis; A positive (or reactive) HBV-DNA or HCV-RNA by PCR (qualitative) indicates the presence of virus that can be passed to others, whereas the negative result (non-reactive) usually means the virus cannot be spread to others; “Occult hepatitis B virus” (HBV) infection is generally defined as the detection of HBV-DNA in the serum or liver tissue of patients who test negative for hepatitis B surface antigen.

Peer review

The authors reported the prevalence rates of HBV or HCV in HIV-positive patients in south Indian area and suggested the higher replication status of HBV or HCV as the disease status of HIV infection progressed. The paper is well written.

Footnotes

Supported by a grant-in-aid for “Referral Center for Chronic Hepatitis and Molecular Virology” at Department of Microbiology, Faculty of Medicine, University of Madras from the Indian Council of Medical Research India

S- Editor Zhu LH L- Editor Rampone B E- Editor Wang HF

References

- 1.McCarron B, Main J, Thomas HC. HIV and hepatotropic viruses: interactions and treatments. Int J STD AIDS. 1997;8:739–745; quiz 745-746. doi: 10.1258/0956462971919192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Soriano V, Barreiro P, Nuñez M. Management of chronic hepatitis B and C in HIV-coinfected patients. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2006;57:815–818. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkl068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.McNair AN, Main J, Thomas HC. Interactions of the human immunodeficiency virus and the hepatotropic viruses. Semin Liver Dis. 1992;12:188–196. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-1007390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Horvath J, Raffanti SP. Clinical aspects of the interactions between human immunodeficiency virus and the hepatotropic viruses. Clin Infect Dis. 1994;18:339–347. doi: 10.1093/clinids/18.3.339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chung RT. Hepatitis C and B viruses: the new opportunists in HIV infection. Top HIV Med. 2006;14:78–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dworkin BM, Stahl RE, Giardina MA, Wormser GP, Weiss L, Jankowski R, Rosenthal WS. The liver in acquired immune deficiency syndrome: emphasis on patients with intravenous drug abuse. Am J Gastroenterol. 1987;82:231–236. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Benhamou Y. Antiretroviral therapy and HIV/hepatitis B virus coinfection. Clin Infect Dis. 2004;38 Suppl 2:S98–S103. doi: 10.1086/381451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.2006 Report on the Global AIDS Epidemic. Available from: http: //www.unaids.org/en/HIV_data/2006GlobalReport/default.asp Accessed on 10.6.2007.

- 9.Alter MJ. Epidemiology of viral hepatitis and HIV co-infection. J Hepatol. 2006;44:S6–S9. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2005.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lauer GM, Walker BD. Hepatitis C virus infection. N Engl J Med. 2001;345:41–52. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200107053450107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tandon BN, Acharya SK, Tandon A. Epidemiology of hepatitis B virus infection in India. Gut. 1996;38 Suppl 2:S56–S59. doi: 10.1136/gut.38.suppl_2.s56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chandra M, Khaja MN, Farees N, Poduri CD, Hussain MM, Aejaz Habeeb M, Habibullah CM. Prevalence, risk factors and genotype distribution of HCV and HBV infection in the tribal population: a community based study in south India. Trop Gastroenterol. 2003;24:193–195. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chowdhury A, Santra A, Chaudhuri S, Dhali GK, Chaudhuri S, Maity SG, Naik TN, Bhattacharya SK, Mazumder DN. Hepatitis C virus infection in the general population: a community-based study in West Bengal, India. Hepatology. 2003;37:802–809. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2003.50157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sud A, Singh J, Dhiman RK, Wanchu A, Singh S, Chawla Y. Hepatitis B virus co-infection in HIV infected patients. Trop Gastroenterol. 2001;22:90–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kumarasamy N, Solomon S, Flanigan TP, Hemalatha R, Thyagarajan SP, Mayer KH. Natural history of human immunodeficiency virus disease in southern India. Clin Infect Dis. 2003;36:79–85. doi: 10.1086/344756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bhattacharya S, Badrinath S, Hamide A, Sujatha S. Co-infection with hepatitis C virus and human immunodeficiency virus among patients with sexually transmitted diseases in Pondicherry, South India. Indian J Pathol Microbiol. 2003;46:495–497. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hussain T, Kulshreshtha KK, Sinha S, Yadav VS, Katoch VM. HIV, HBV, HCV, and syphilis co-infections among patients attending the STD clinics of district hospitals in Northern India. Int J Infect Dis. 2006;10:358–363. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2005.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Padmapriyadarsini C, Chandrabose J, Victor L, Hanna LE, Arunkumar N, Swaminathan S. Hepatitis B or hepatitis C co-infection in individuals infected with human immunodeficiency virus and effect of anti-tuberculosis drugs on liver function. J Postgrad Med. 2006;52:92–96. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gupta S, Singh S. Hepatitis B and C virus co-infections in human immunodeficiency virus positive North Indian patients. World J Gastroenterol. 2006;12:6879–6883. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v12.i42.6879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Poudel KC, Jimba M, Okumura J, Wakai S. Emerging co-infection of HIV and hepatitis B virus in far western Nepal. Trop Doct. 2006;36:186–187. doi: 10.1258/004947506777978244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shih JW, Cheung LC, Alter HJ, Lee LM, Gu JR. Strain analysis of hepatitis B virus on the basis of restriction endonuclease analysis of polymerase chain reaction products. J Clin Microbiol. 1991;29:1640–1644. doi: 10.1128/jcm.29.8.1640-1644.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Panigrahi AK, Nanda SK, Dixit RK, Acharya SK, Zuckerman AJ, Panda SK. Diagnosis of hepatitis C virus-associated chronic liver disease in India: comparison of HCV antibody assay with a polymerase chain reaction for the 5' noncoding region. J Med Virol. 1994;44:176–179. doi: 10.1002/jmv.1890440211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.National AIDS Control Organization (NACO). HIV/AIDS epidemiological Surveillance & Estimation report for the year 2005. Available from: http: //www.nacoonline.org/Accessed on 10.6; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rockstroh JK. Management of hepatitis B and C in HIV co-infected patients. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2003;34 Suppl 1:S59–S65. doi: 10.1097/00126334-200309011-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dodig M, Tavill AS. Hepatitis C and human immunodeficiency virus coinfections. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2001;33:367–374. doi: 10.1097/00004836-200111000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tien PC. Management and treatment of hepatitis C virus infection in HIV-infected adults: recommendations from the Veterans Affairs Hepatitis C Resource Center Program and National Hepatitis C Program Office. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005;100:2338–2354. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2005.00222.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yachimski P, Chung RT. Update on Hepatitis B and C Coinfection in HIV. Curr Infect Dis Rep. 2005;7:299–308. doi: 10.1007/s11908-005-0063-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schooley RT. HIV and hepatitis C virus coinfection: bad bedfellows. Top HIV Med. 2005;13:112–116. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Koch S, Göbels K, Oette M, Heintges T, Erhardt A, Häussinger D. [HIV-HBV-coinfection--diagnosis and therapy] Dtsch Med Wochenschr. 2006;131:1873–1877. doi: 10.1055/s-2006-949173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Murphy MJ. Managing HIV/HBV coinfection can challenge some clinicians. HIV Clin. 2003;15:6–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Miller AO. Management of HIV/HBV coinfection. MedGenMed. 2006;8:41. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shire NJ, Sherman KE. Management of HBV/HIV-coinfected Patients. Semin Liver Dis. 2005;25 Suppl 1:48–57. doi: 10.1055/s-2005-915646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wright TL, Hollander H, Pu X, Held MJ, Lipson P, Quan S, Polito A, Thaler MM, Bacchetti P, Scharschmidt BF. Hepatitis C in HIV-infected patients with and without AIDS: prevalence and relationship to patient survival. Hepatology. 1994;20:1152–1155. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lascar RM, Gilson RJ, Lopes AR, Bertoletti A, Maini MK. Reconstitution of hepatitis B virus (HBV)-specific T cell responses with treatment of human immunodeficiency virus/HBV coinfection. J Infect Dis. 2003;188:1815–1819. doi: 10.1086/379896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.O'Leary JG, Chung RT. Management of hepatitis C virus coinfection in HIV-infected persons. AIDS Read. 2006;16:313–316, 313-316. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chamot E, Hirschel B, Wintsch J, Robert CF, Gabriel V, Déglon JJ, Yerly S, Perrin L. Loss of antibodies against hepatitis C virus in HIV-seropositive intravenous drug users. AIDS. 1990;4:1275–1277. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199012000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sorbi D, Shen D, Lake-Bakaar G. Influence of HIV disease on serum anti-HCV antibody titers: a study of intravenous drug users. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr Hum Retrovirol. 1996;13:295–296. doi: 10.1097/00042560-199611010-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]