Abstract

Arsenic (As) is posing serious health concerns in South East Asia where rice, an efficient accumulator of As, is prominent crop. Salicylic acid (SA) is an important signaling molecule and plays a crucial role in resistance against biotic and abiotic stress in plants. In present study, ameliorative effect of SA against arsenate (AsV) toxicity has been investigated in rice (Oryza sativa L.). Arsenate stress hampered the plant growth in terms of root, shoots length, and biomass as well as it enhanced the level of H2O2 and MDA in dose dependent manner in shoot. Exogenous application of SA, reverted the growth, and oxidative stress caused by AsV and significantly decreased As translocation to the shoots. Level of As in shoot was positively correlated with the expression of OsLsi2, efflux transporter responsible for root to shoot translocation of As in the form of arsenite (AsIII). SA also overcame AsV induced oxidative stress and modulated the activities of antioxidant enzymes in a differential manner in shoots. As treatment hampered the translocation of Fe in the shoot which was compensated by the SA treatment. The level of Fe in root and shoot was positively correlated with the transcript level of transporters responsible for the accumulation of Fe, OsNRAMP5, and OsFRDL1, in the root and shoot, respectively. Co-application of SA was more effective than pre-treatment for reducing As accumulation as well as imposed toxicity.

Keywords: arsenate, salicylic acid, rice seedlings, antioxidants, Fe transporters

Introduction

Arsenic (As) is posing a serious health concern in South East Asia especially in Bangladesh and West Bengal in India. Long term As exposure leads to skin lesions and various types of cancers (Kumar et al., 2015). Safe level of As in drinking water is10 μg l-1, as recommended by World Health Organization in 1993, while the level of As in ground water has been reported up to 3200 μg l-1 in West Bengal and Bangladesh that is enough to show the severity of problem (McCarty et al., 2011). Arable land can be contaminated through irrigation by As rich water. More than 90% production of rice comes from South East Asia that is heavily contaminated by As, thus significant amount of As also accumulates in various parts of rice which serves as a major entry route for As in to food chain. Presence of As in grains also hampers the nutritional value of rice in terms of trace nutrients and amino acids (Kumar et al., 2014a).

Arsenic is non-essential element for plant and present in environment both in inorganic as well as organic forms. Arsenate (AsV) and arsenite (AsIII) are predominant inorganic forms. As toxicity symptoms in plants range from inhibition of root growth, photosynthesis to death of plant (Mishra et al., 2014; Kumar et al., 2015). Arsenate shows structural analogy with phosphate so it is mainly transported through high affinity phosphate transporters (Tripathi et al., 2007). In paddy field, AsIII is the predominant chemical species of As due to anaerobic growing conditions (Takahashi et al., 2004). Further, most of the As taken up by the plants is also reduced and stored as AsIII (Pickering et al., 2000; Mishra et al., 2013). Arsenite is transported through aquaporin channels. Two major AsIII transporters, Lsi1 and Lsi2 have been reported in rice. Lsi1 is localized at the distal side of both exodermis and endodermis cells of rice roots and mediates the influx of AsIII. Lsi2 is localized at the proximal side of both exodermis and endodermis cells and plays an important role in AsIII transport to the shoots and ultimately to the rice grains (Ma et al., 2008). Arsenate can replace phosphate from many biochemical reactions leading to disruption of energy flow while AsIII interferes with functioning of proteins and enzymes through thiol interaction (Finnegan and Chen, 2012). As is a redox active metalloid and induces the generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) leading to lipid peroxidation, disruption of cellular redox state, and associated toxicity (Finnegan and Chen, 2012). In rice As mediated redox imbalance has been shown to the major factor causing toxicity (Srivastava et al., 2014). To cope up with ROS production plants are equipped with various antioxidant enzymes and molecules (GSH, Ascorbate). GSH also serves as substrate for phytochelatins (PCs), the metal and metalloids chelating ligands, therefore, reduces free As inside cell (Kumar et al., 2014b).

Salicylic acid and its derivative (acetylsalicylic acid) have been used for therapeutic purpose since more than a century. SA is synthesized by two pathways, the isochorismate pathway and the phenylalanine ammonia-lyase pathway (Vlot et al., 2009). SA is an important signaling molecule and its role in protection against various biotic and abiotic stresses has been well studied in plants (Yuan and Lin, 2008; Vlot et al., 2009). Upon pathogen attack endogenous level of SA gets enhanced and binds to catalase (CAT) that leads to enhanced level of H2O2. The H2O2 serves as secondary messenger to induce the expression of pathogen related proteins and ultimately initiates systemic acquired resistance (Vlot et al., 2009). SA has been reported to provide protection against heavy metal stress such as, against mercury in Medicago sativa (Zhou et al., 2009), cadmium stress in barley, rice and soybean (Metwally et al., 2003; Guo et al., 2007; Noriega et al., 2012), and against nickel stress in mustard (Yusuf et al., 2012). Guo et al., (2007) hypothesized that enhanced level of H2O2 by SA serves as secondary messenger to improve plant defense against abiotic stress. SA is reported to abate the chlorosis under iron deficient conditions and also promotes iron (Fe) uptake and translocation in Arachis hypogaea (Kong et al., 2014) and enhanced mineral nutrient uptake including Fe in maize (Gunes et al., 2007).

Iron acquisition mechanism in various plants is divided in two main categories: Strategy I in non-graminaceous plants and Strategy II in graminaceous plants (Römheld and Marschner, 1986). The two main processes in the Strategy I are the reduction of ferric chelates (Fe+3-chelate) at the root surface and the absorption of the generated ferrous (Fe+2) ions across the root plasma membrane (Kobayashi and Nishizawa, 2012). Rice belongs to family graminae which uses strategy II for Fe uptake where the plant roots secretes mugenic acid (MA) that forms Fe+3-MA complex and is taken up by root cells by YSL transporters (Kobayashi and Nishizawa, 2012). There are several Fe transporters in which OsFRDL1, OsYSL2, and OsNRAMP5 follow strategy II and uptake only chelated Fe+3, but rice also has a unique transporter OsIRT1 which enables the plant to directly uptake the Fe+2 from soil beyond the strategy II (Ishimaru et al., 2006). The key regulator of Fe transporters is OsIRO2, strongly induced under iron deficient conditions (Ogo et al., 2007). OsFRDL1 is expressed in rice root pericycle and encodes citrate effluxer that is required for efficient Fe translocation (Yokosho et al., 2009) and OsYSL2 is responsible for long distance transport of chelated Fe+3 to sink tissues (Ishimaru et al., 2010). Along with the Fe+3, OsNRAMP5 also contributes to Mn+2 and Cd+2 transport in rice (Ishimaru et al., 2012).

This study is hypothesized to investigate positive impact of SA on AsV tolerance in rice. We analyzed changes in As accumulation, oxidative stress, antioxidant enzymes activities, AsIII, and Fe transporters in AsV exposed plants under co-application, and pre-treatment of SA.

Materials and Methods

Growth Conditions and Experimental Design

Seeds of Oryza sativa cv. Pant4 collected from Masina Research Centre, Pvt. Ltd., Bihar (India), were surface sterilized using 10% H2O2 for 30 s and washed with Milli Q water. Seeds were germinated on moist pre-sterilized blotting sheets in a tray, placed in seed germinator for 4 days at 25°C, relative humidity was 65%. After 7 days, 50 uniform size seedlings were selected and placed in 150 ml beakers, covered with black sheet, containing 100 ml of 100% Hewitt nutrient medium, prepared in Milli-Q water (pH 6.8–7.0) and grown for another 10 days under light intensity 210 μM cm-2s-1 (16/8 h; day/night). 10 days old plants were provided AsV (25 and 50 μM) using the salt Na2HAsO4 and SA (100 μM) in the nutrient medium and grown for 7 days. Plants treated by 25 and 50 μM AsV, 100 μM SA for 7 days abbreviated as AsV25, AsV50 and SA, respectively. Plants treated with AsV25, AsV50 supplemented with SA abbreviated as SA + AsV25and SA + AsV50. For Pre-treatment of SA, plants were grown in 100 μM SA for 3 days and then transferred to Hewitt solution containing AsV25, AsV50for 7 days and they are abbreviated as SA Pre+AsV25and SA Pre + AsV50. Plants grown in AsV deprived medium termed as SA Pre and plants grown only in Hewitt solution served as control.

Estimation of Chlorophyll and Carotenoids

Fresh leaves (0.1 g) were crushed in 5 ml of 80% acetone and centrifuged at 10,000 × g for 10 min. The supernatant was used for estimation of chlorophyll by Arnon (1949) method and carotenoids by Duxbury and Yentsch (1956) method.

Estimation Hydrogen Peroxide and MDA

Fresh leaves (0.5 g) were crushed in 5 ml of 0.1% trichloroacetic acid and centrifuged at 10,000 × g for 10 min. The supernatant was used for estimation of MDA and H2O2. MDA and H2O2 by Heath and Packer (1968) and Velikova et al. (2000), respectively.

Assay of Antioxidant Enzymes

Fresh leaves (0.3 g) were ground in liquid N2 using a mortar, and homogenized in 3 ml of buffer containing 50 mM potassium phosphate buffer (pH 7.8) and 1% (w/v) polyvinylpyrrolidone. The homogenate was centrifuged at 8000 × g at 4°C for 15 min. and supernatant was used for ascorbate peroxidase (APX), guaiacol peroxidase (GPX), CAT, superoxide dismutase (SOD), and Nitrate reductase (NR) activity, and nitrite and soluble protein concentration.

The activity of SOD (EC 1.15.1.1) was measured by Beauchamp and Fridovich (1971), APX (EC 1.11.1.11) by Nakano and Asada (1981), GPX (EC 1.11.1.7) by Kato and Shimizu (1987), CAT (EC 1.11.1.6) by Scandalios et al. (1983), NR (EC 1.7.99.4), and nitrite by Hageman and Reed (1980).

Estimation of Non-Protein Thiolic Metabolites and Ascorbic Acid

The level of GSH and GSSG was measured by following the protocol of Hissin and Hilf (1976). Plant material (500 mg) was frozen in liquid nitrogen and homogenized in 0.1 M sodium phosphate buffer (pH 8.0) containing 25% meta-phosphoric acid. The homogenate was centrifuged at 20,000 × g for 20 min at 4°C. Total glutathione (GSSG and GSH) content was determined fluorometrically in the supernatant after 15 min incubation with o-phthaldialdehyde (OPT). Fluorescence intensity was recorded at 420 nm after excitation at 350 nm on a Hitachi F 7000 fluorescence spectrophotometer.

Non-protein thiol (NPT) content was measured by following the method of Ellman (1959). The concentration of PCs was calculated as PCs = NPT – (GSH + GSSG; Duan et al., 2011).

For estimation of ascorbic acid (Asc), fresh leaves (0.5 g) were crushed in 5 ml of 0.1% trichloroacetic acid and homogenate was centrifuged at 10,000 × g for 10 min. The supernatant was used for estimation of Asc by Shukla et al. (1979).

Element Estimation

The elements (As and Fe) content was determined following Mallick et al. (2012). Briefly, plant tissues were washed three times with Milli Q water and plants separated in root and shoot and oven dried at 70°C. Dried plant tissues (root 300 and shoot 500 mg) were digested in HNO3: HCl (3:1). Digested samples were filtered through Whatman filter paper 42 and volume was made to 10 ml by Milli-Q water. As and Fe were estimated by using AAS (GBC Avanta S, USA) fitted with a hydride generator (MDS 2000) using NaH2BO4+NaOH (3 M) and HCl (3 M). The values were presented in μg per gram dry weight (μg g-1dw).

Endogenous Salicylic Acid Estimation

Presence of SA in shoot samples were analyzed by HPLC (Dionex Ultimate 3000) using UV detector at 210 nm by following the method of Pan et al. (2010). The mobile phase was programmed with linear gradient of A (0.1% of formic acid in methanol) and B (0.1% of formic acid in water) as 0–20 min; 30–100% A, 20–22 min; 100% A and then 22–25 min; 100–30% of A. Flow rate was maintained at 0.3 ml min-1. Retention time for SA was recorded at 22.4 min.

Gene Expression Analysis Using Quantitative RT-PCR

Approximately 5 μg, RNase free DNase-treated, total RNA isolated from roots of rice plants was reverse-transcribed using SuperScriptII (Fermentas, USA), following the manufacturer’s recommendation. The synthesized cDNA was diluted 1:5 in DEPC water and subjected to quantitative RT-PCR (qRT-PCR) analysis. The qRT-PCR was performed using an ABI 7500 instrument (ABI Biosystems, USA) using primers listed in Supplementary Table S1. Each qPCR reaction contained 5 μl of SYBR Green Supermix (ABI Biosystems, USA), 1 μl of the diluted cDNA reaction mixture (corresponding to 5 ng of starting amount of RNA) and 10 pM of each primer in a total reaction volume of 10 μl. The qPCR reactions were performed under following conditions: 10 min at 95°C and 40 cycles of the one step thermal cycling of 3 s at 95°C and 30 s at 60°C in a 96-well reaction plate. Actin gene was used as an internal control to estimate the relative transcript levels of the target gene. Specificity of amplicons generated in qPCR reactions was verified by melt curve analysis. Each qPCR reaction was performed in triplicate (technical replicates) for each biological replicate (three for each treatment). Relative gene expression was calculated using ΔΔCT method (Livak and Schmittgen, 2001).

Statistical Analysis and Analytical Quality Control

The whole experiment was set up in the randomized block design. The data were subjected to Duncan’s Multiple Range Test (DMRT) for the analysis of significant difference between the treatments. Analytical data quality of the elements, was ensured through repeated analysis (n = 6) of Standard Reference Material. Standard Certified reference material (CRM 028-050) used for the accuracy of the AAS procured from Resource Technology Corporation, USA (Lot no. IH 028), and the values obtained varied between -3.97 to 22.86% error between ten measurements. The blanks were run all the time to eliminate the background noise.

Results

Morphology and Photosynthetic Pigments

Arsenate had deleterious impact on plant growth. A dose dependent decrease of 6 and 17% at 25 μM and 26 and 31% at 50 μM AsV was observed in root and shoot, respectively, than control. SA alone treatment enhanced the root and shoot length by 39 and 19%, respectively, than control. Co-application of SA and AsV50 enhanced the root and shoot growth significantly (58 and 36%, respectively) than 50 μM AsV alone treated plants. SA pre-treated plants also experienced less toxicity during exposure to AsV. Arsenate induced reduction in biomass was also significantly recovered by SA supplementation. Under AsV stress total chlorophyll was reduced significantly in dose dependent manner with maximum approximately 22% reduction at 50 μM AsV than control while carotenoid content was increased significantly in AsV50 treatment than control. SA co-application with AsV, reverted chlorophyll loss caused by AsV stress (Table 1).

Table 1.

Effect on shoot, root lengths (cm), fresh-weight (mg), total chlorophyll (mg g-1fw), and carotenoid content (mg g-1fw) Oryza sativa after 7 days of treatment with different combinations of Arsenate (AsV) and Salicylic acid (SA).

| Root length | Shoot length | Biomass | Total chl | Carotenoids | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | 3.88cd ± 0.26 | 26.3de ± 1.8 | 274.24d± 0.01 | 2.29de ± 0.06 | 0.15ab ± 0.008 |

| SA | 5.40g ± 0.36 | 31.3f ± 2.5 | 345.51f ± 0.0 | 2.44f ± 0.08 | 0.15bc ± 0.008 |

| AsV25 | 3.63bc ± 0.29 | 21.8bc ± 1.4 | 226.84ab ± 0.07 | 1.94b ± 0.02 | 0.18ef ± 0.004 |

| AsV50 | 2.85a ± 0.19 | 18.0a ± 1.2 | 218.94a ± 0.07 | 1.79a ± 0.07 | 0.18f ± 0.006 |

| SA + AsV25 | 4.88f ± 0.33 | 26.3de ± 1.7 | 266.79cd ± 0.06 | 2.31e ± 0.01 | 0.14a ± 0.004 |

| SA + AsV50 | 4.50ef ± 0.30 | 24.5cd ± 1.9 | 248.73bcd ± 0.01 | 2.17c ± 0.02 | 0.16cd ± 0.001 |

| SA Pre | 4.28de ± 0.29 | 28.1e ± 1.9 | 312.84e ± 0.016 | 2.48f ± 0.05 | 0.16cd ± 0.001 |

| SA Pre +A sV25 | 3.52bc ± 0.28 | 24.3cd ± 1.6 | 253.36bcd ± 0.08 | 2.22cde ± 0.05 | 0.17de ± 0.007 |

| SA Pre + AsV50 | 3.33ab ± 0.26 | 20.6ab ± 1.4 | 239.91abc ± 0.01 | 2.19cd ± 0.05 | 0.17de ± 0.008 |

Values marked with same alphabets are not significantly different (DMRT, p < 0.05). All the values are means of three replicates ±SD.

Element Content in Root and Shoot

The rice plants accumulated significant amount of As in upon exposure to AsV in dose dependant manner. In all treatments more than 90% of As was confined in to the roots. SA co-application to AsV treated plants had no significant impact on As accumulation in root. However, the shoot As was reduced significantly, i.e., around 30% reduction in both SA + AsV25 and SA + AsV50 than AsV alone treated plants was observed. SA pre-treated plants also accumulated 16 and 17% less As in shoot upon exposure to 25 and 50 μM AsV, respectively, (Table 2).

Table 2.

Accumulation (μg g-1dw) of Arsenic (As) and Fe in the root and shoot of Oryza sativa after 7 days of treatment with different combinations of AsV and SA.

| As root | As shoot | Fe root | Fe shoot | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | – | – | 364.2a ± 18.1 | 60.2cde ± 5.1 |

| SA | – | – | 403.3a ± 30.0 | 68.3e ± 7.1 |

| AsV25 | 317.82a ± 66.2 | 28.84bc ± 2.7 | 566.6bc ± 49.2 | 48.4ab ± 5.8 |

| AsV50 | 454.26b ± 22.2 | 38.00d ± 4.1 | 632.5c ± 61.3 | 40.2a ± 3.3 |

| SA + AsV25 | 290.83a ± 42.9 | 19.96a ± 2.3 | 522.4b ± 63.1 | 62.8de ± 3.9 |

| SA + AsV50 | 426.74b ± 56.9 | 26.55bc ± 2.9 | 528.8b ± 41.1 | 58.3cde ± 4.4 |

| SA Pre | – | – | 409.2a ± 17.7 | 64.4de ± 4.6 |

| SA Pre + AsV25 | 302.56a ± 46.9 | 24.22ab ± 2.7 | 486.6b ± 38.4 | 55.8bcd ± 5.8 |

| SA Pre + AsV50 | 432.32b ± 53.3 | 31.19c ± 1.8 | 551.4b ± 43.6 | 52.3bc ± 6.6 |

Values marked with same alphabets are not significantly different (DMRT, p < 0.05). All the values are means of four replicates ±SD.

Arsenate treatment significantly enhanced total Fe accumulation in comparison to control plants. However, the most of the accumulated Fe was localized in the roots. The translocation of Fe to shoot was reduced drastically (6% of total accumulation at AsV50) in AsV treated plants which was 33% lower than control shoot. Co-application as well as pre-treatment of SA reduced the total Fe accumulation in comparison to AsV alone, however, its translocation to shoots increased significantly, i.e., 30 and 45% increased at SA + AsV25 and SA + AsV50 than AsV alone treated shoots and the level of Fe in shoots were comparable to control (Table 2).

Oxidative Stress and Antioxidants

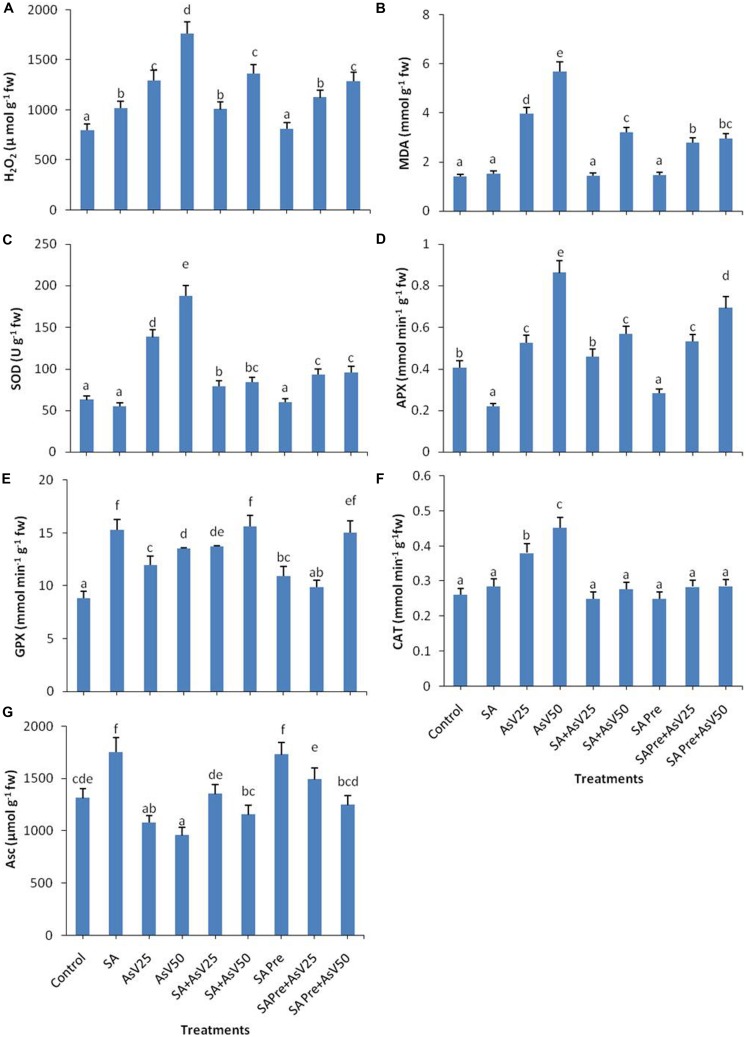

Salicylic acid alone treatment had no significant impact on MDA content in rice shoot while H2O2 content was enhanced by 28% than control. Arsenate treatment enhanced the MDA content by ca. three- and fourfolds at 25 and 50 μM AsV exposed plants, respectively, than control. Similar trend was observed in H2O2 content. Pre-treatments as well as co-application of SA and AsV has reduced the level of MDA and H2O2than AsV alone treated plants, although co-application was more effective than pre-treatment (Figures 1A,B).

FIGURE 1.

Effect on (A) H2O2, (B) MDA, (C) SOD, (D) APX, (E) GPX, (F) CAT, and (G) Ascorbate in shoot of the Oryza sativa after 7 days of treatment with different combinations of Arsenate (AsV) and Salicylic acid (SA). Values marked with same alphabets are not significantly different (DMRT, p < 0.05). All the values are mean of three replicates ±SD.

Salicylic acid treatment also moderated AsV induced antioxidant activities. SOD activity got enhanced ca. two- and threefolds, respectively, in AsV25 and AsV50 treated plants in shoot than control. Co-application of SA and AsV significantly reduced SOD activity which was about 42 and 55% than AsV25 and AsV50, respectively. SA pre-treatment to AsV exposed plants showed 32 and 50% less SOD activity the respective AsV treatments (Figure 1C).

Salicylic acid alone treatment reduced the APX activity to approximately half while 50 μM AsV treatment approximately doubled the APX activity than control. Co-application of SA and AsV50 reduced APX activity by 34% also SA pre-treatment (SA Pre + AsV50) reduced APX activity by 20% than AsV50 treated plants (Figure 1D). SA alone treatment enhanced the GPX activity by ca. twofold, furthermore AsV treatment also enhanced the activity significantly than control. Co-application of SA and AsV also enhanced GPX activity than corresponding alone AsV treated plants (Figure 1E). Under AsV stress, CAT activity was enhanced 45 and 72% at 25 and 50 μM, respectively, than control. Co-application or pre-treatment of SA and AsV, reduced the CAT activity than AsV alone exposed plants (Figure 1F). SA alone treatment has enhanced the Asc content by 33% while exposure to 50 μAsV reduced the Asc level by upto 27% than control. Co-application of SA and AsV further enhanced the Asc content significantly than corresponding AsV alone treated plants. SA pre-treatment also enhanced the level of Asc upon AsV exposure in all treatments than corresponding AsV exposed plants (Figure 1G).

Nitrate Reductase, Nitrite, and Endogenous Level of SA

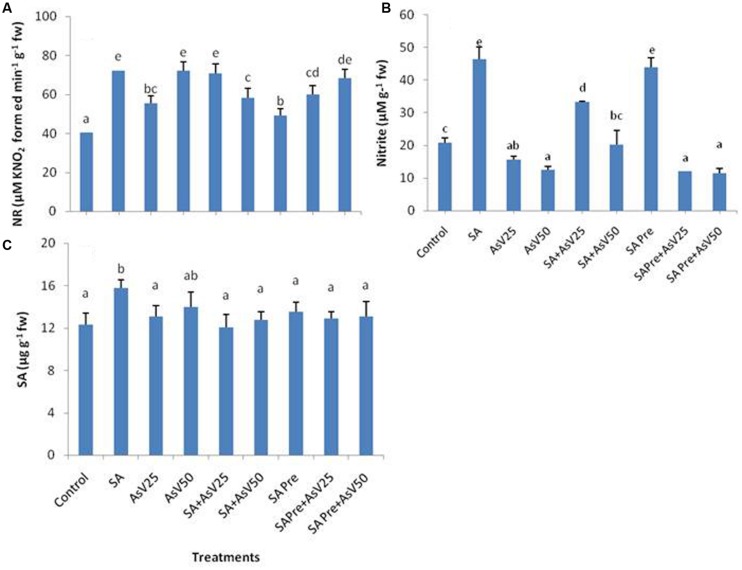

Nitrate reductase activity was significantly enhanced by SA as well as AsV treated plants in comparison to control. Co-application of SA with lower AsV (25 μM) has enhanced the NR activity significantly while with higher AsV (50 μM) NR activity was reduced significantly than As alone treatments. SA pre-treatment to AsV exposed plants has no significant impact on NR activity than corresponding alone AsV exposed plants (Figure 2A).

FIGURE 2.

Effect on (A) Nitrate reductase, (B) Nitrite and (C) Endogenous level of SA in shoot of the Oryza sativa after 7 days of treatment with different combinations of AsV and SA. Values marked with same alphabets are not significantly different (DMRT, p < 0.05). All the values are means of three replicates ±SD.

The level of nitrite was almost doubled in SA alone treated plants, while a dose dependent decrease in nitrite level was observed under AsV stress plants than control. Co-application of SA and AsV enhanced the nitrite level in comparison to AsV alone exposed plants. SA pre-treated plants had almost double nitrite than control. However, when SA pre-treated plants were exposed to AsV the levels of nitrite was lower than control and were comparable to AsV alone treated plants (Figure 2B). There was no significant change in level of endogenous level of SA in shoot in all treatments except for SA alone treated plants where endogenous level of SA was enhanced significantly than control (Figure 2C).

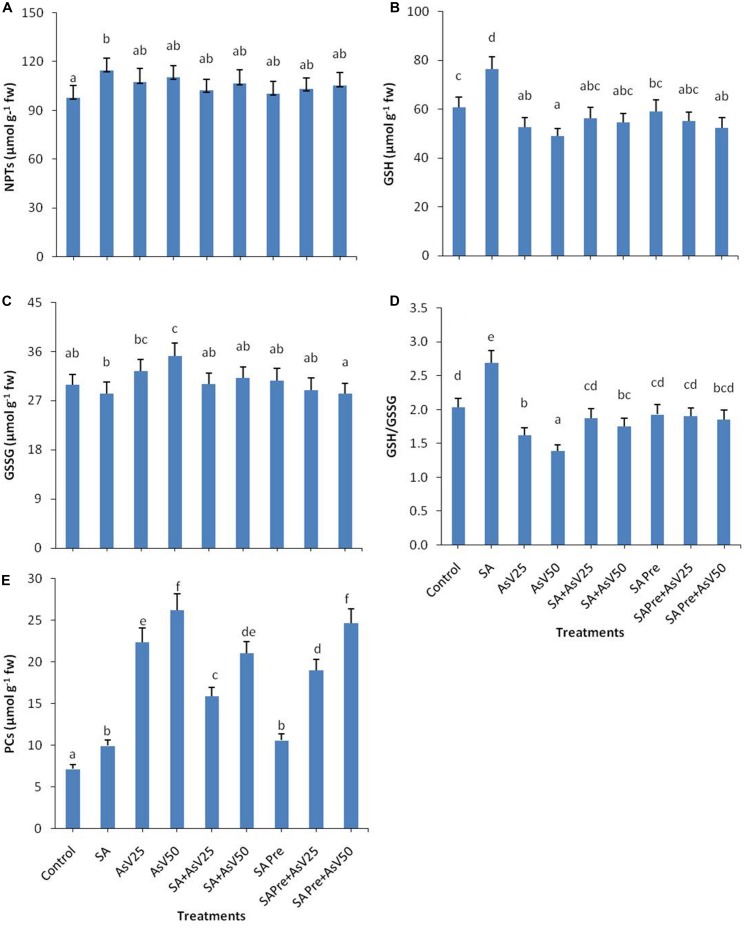

Non-Protein Thiol Metabolism

The level of total non-protein thiol (NPT) did not show any significant change in response to the treatments in comparison to control except for SA alone treated plant (Figure 3A). SA treatment has enhanced the GSH level by 25% while AsV stress has reduced the GSH content in dose dependent manner than control. Co-application of SA and AsV enhanced GSH content 7 and 11% than corresponding AsV alone treated plants though the levels were not statistically significant different than control. Pre-treatment of SA with AsV had no significant impact on GSH level than corresponding AsV alone treated plants (Figure 3B). Alone SA treatment had no significant impact on GSSG level while AsV50 has significantly enhanced GSSG content than control (Figure 3C). Ratio of GSH/GSSG was enhanced by 32%in SA treatment plants while in AsV treated plant the ratio was reduced by 20 and 31% in dose dependent manner than control. Co-application of SA and AsV has enhanced the GSH/GSSG ratio than their corresponding AsV alone treated plants. SA pre-treated AsV exposed plants also showed enhanced GSH/GSSG ratio than AsV alone treated plants (Figure 3D).

FIGURE 3.

Effect on (A) NPTs, (B) GSH, (C) GSSG, (D) ratio of GSH/GSSG, and (E) Phytochelatins (PCs) in shoot of the Oryza sativa after 7 days of treatment with different combinations of AsV and SA. Values marked with same alphabets are not significantly different (DMRT, p < 0.05). All the values are means of three replicates ±SD.

Both SA alone and AsV alone treatments enhanced the level of PCs to 1.4 and up to 3.5-fold (at AsV50), respectively, as compared to control. Co-application of SA and AsV reduced the PCs accumulation by 29 and 19% than corresponding alone AsV treated plants though the values were still significantly higher than controls. Similar effects were observed in SA pre-treated plants both with and without AsV (Figure 3E).

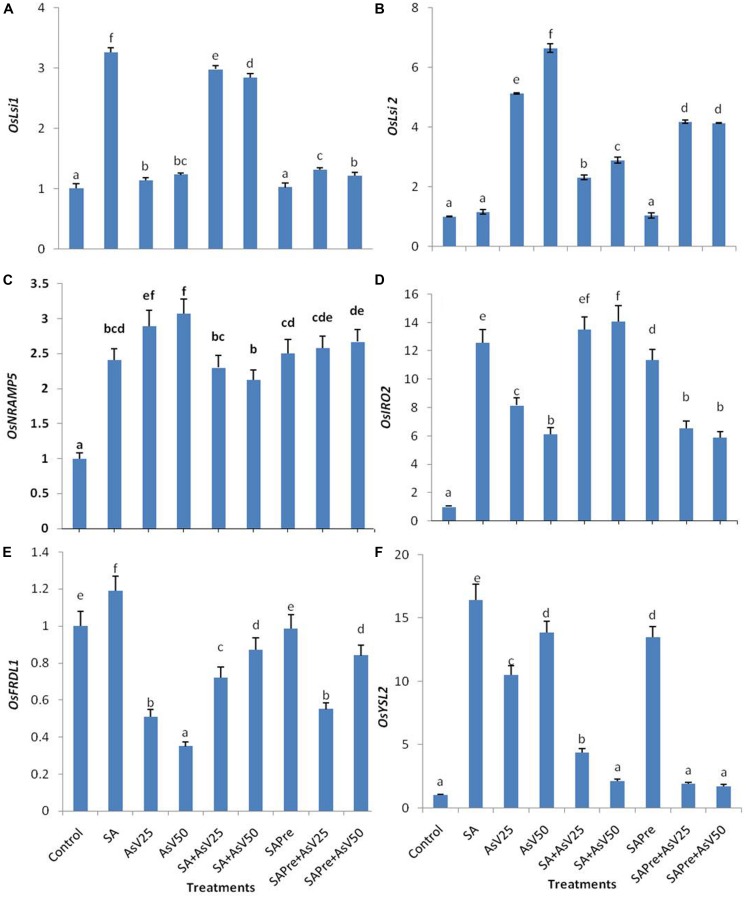

Arsenite and Iron Transporters

Salicylic acid alone treatment enhanced the expression level of OsLsi1 to ca. threefold than control. Arsenate alone treatment also enhanced OsLsi1 expression significantly in comparison to control though the levels were far lower than SA alone. Co-application of SA and AsV enhanced OsLsi1 expression around twofolds than AsV alone treated roots. Pre-treatment of SA, with or without AsV, had no significant impact on OsLsi1expressionin comparison to control or respective AsV alone treatments (Figure 4A).

FIGURE 4.

Relative expression of transcript level of iron transporters (A)OsLsi1,(B)OsLsi2,(C)OsNRAMP5, (D)OsIRO2, (E)OsFRDL1, and (F)OsYSL2 in roots of Oryza sativa after 7 days of treatment with different combinations of AsV and SA. Values marked with same alphabets are not significantly different (DMRT, p < 0.05). All the values are means of three replicates ±SD.

Arsenate exposure enhanced the OsLsi2 expression level to ca. five- and sevenfold in dose dependent manner than control. Co-application of SA and AsV as well SA pre-treatment to AsV exposed plants lowered the expression of OsLsi2 in comparison to AsV alone treatments, however, the levels were still significantly higher than control roots (Figure 4B).

The expression of OsNRAMP5 was enhanced more about threefold in AsV treated plant roots, however, SA alone treatment also increased the expression of OsNRAMP5 by about 2.5-folds. Co-application of SA and AsV has reduced the expression level by 20% and 31% in comparison to respective AsV alone exposed plants. SA pre-treatment slightly reduced the expression level of OsNRAMP5 in comparison to AsV alone treatment which was significant at 50 μM AsV.

OsIRO2 expression level enhanced 13-fold in SA treated plants and AsV25 and AsV50 have enhanced ca. eight and ca. sixfold than control. Co-application of SA and AsV further enhanced expression level and that was comparable to SA treated plants. SA pre-treatment to AsV50 stressed plants significantly increased the expression level of OsIRO2 than AsV50alone treated plants.

OsFRDL1 expression level was decreased under AsV stress in dose dependent manner than control. Co-application of SA and AsV enhanced the expression level significantly than corresponding AsV alone treated plants. In SA pre-treated plants exposed to AsV50 the expression level of OsFRDL1 approximately doubled than AsV50 alone treated plants.

OsYSL2 expression level was enhanced to ca. 16-fold in SA alone treated plants and AsV alone treatment enhanced the expression by about 10- and 13-fold in dose dependent manner than control. Co-application of SA and AsV reduced the expression level than SA alone as well as corresponding AsV alone treated plants. SA pre-treatment also enhanced the expression level 13-fold than control. SA pre-treatment to AsV stressed plants sharply declined the expression level than corresponding alone AsV treated plants (Figures 4C–F).

Discussions

Salicylic acid serves as an important signaling molecule in plant system which has been shown to play role in against heavy metal toxicity (as detailed in introduction). The present experiment was designed to investigate the ameliorative effect of SA during As toxicity. The co-application and pre-treatment of SA with As was used to investigate persistence of signaling aspects of SA.

Arsenic is well known to adversely affect the plant growth and development upon its accumulation (Kumar et al., 2015). In present study as well a significant amount of As was accumulated by the rice plant that hampered the plant growth severely. Application of SA, either co- or pre- treatment with AsV has significantly reduced the total accumulation of As (Root + shoot) with more reduction in the shoot. Though, the co-application of SA was more effective in reducing As accumulation than pre-treatment of SA. Thus, SA treatment has negatively impacted the root to shoot translocation of As. This might be due to SA-mediated down regulation of root to shoot As transporters. In present study OsLsi2, transporter responsible for root to shoot AsIII transport in rice (Ma et al., 2008), has been found to be down regulated at mRNA level. Since AsIII is the dominant form inside the plant (Pickering et al., 2000; Mishra et al., 2013) and also probably the main As species translocated to the shoots. Thus, down regulation of OsLsi2 would negatively affect the As accumulation. In the present study As accumulation was positively correlation with OsLsi2 expression level (R = 0.87). Down regulation of OsLsi2was resulted in lower As accumulation in rice shoots in response to thiourea supplementation with As (Srivastava et al., 2014). OsLsi1 is primarily responsible for AsIII transport to root from extracellular medium, was not found correlated with root uptake of Asin present study. This might be due to fact that in present experiment plants were treated with AsV which is transported by the phosphate transporters (Tripathi et al., 2007). Alternatively, SA has been reported to activate ATP-binding cassette (ABC) transporters in soybean (Eichhorn et al., 2006). The ABC transporters are responsible for vacuolar sequestration of As(III)-PC complexes (Song et al., 2010). Therefore, it might be possible that most of the accumulated As in SA treated rice plants were sequestered in root vacuoles in the form of As(III)-PC, as a result less As could be transported to the shoot. Further, SA pre-treatment has been reported to enhance PCs synthesis in maize root (Szalai et al., 2013). Although SA mediated resistance against heavy metal viz., Cd, and Mn, has reported in previous studies (Metwally et al., 2003: Shi and Zhu, 2008) no reduction in the level of accumulation was observed. Since less accumulation of metalloid in shoot might also affect its level in grain which would have great implications with respect to human toxicity through food chain As contamination.

In present study SA treatment has enhanced the plant growth in terms of root, shoot length and biomass. Co-application of SA and AsV, partially restored the plant growth in AsV exposed plants. Growth stimulating effects of SA has been previously reported in soybean (Gutiérrez-Coronado et al., 1998), wheat (Shakirova et al., 2003), and maize (Gunes et al., 2007). This growth restoration by SA could be auxin mediated or due to lowering of As accumulation in shoot. In SA treated wheat seedlings, higher level of auxin has been reported (Shakirova et al., 2003). SA inducible transcription factors (OBP1, OBP2, and OBP3) were found to be responsive to auxin (Kang and Singh, 2000). Pre-treatment of SA also reverted the AsV mediated inhibition of plant growth. In present study, a marked reduction in chlorophyll content was observed in AsV treated plants. Similar results were previously reported by Rahman et al. (2007) in rice and by Mishra et al. (2014) in Ceratophyllum. SA supplementation to AsV treated plants reverted AsV induced chlorosis. Similar reversion of chlorosis was observed in maize under salinity stress (Khodary, 2004). In present study AsV also reduced the Fe content in shoot that may also be responsible for AsV mediated chlorosis while SA has enhanced the iron content in shoot and reverted the chlorosis. Previously Kong et al. (2014) also reported the increased uptake of Fe in Arachis hypogaea by foliar application of SA. SA induces the nitric oxide (NO) synthesis in plants (Zottini et al., 2007) that is reported to enhance the bioavailability of Fe (Graziano and Lamattina, 2007). In present study NR activity and nitrite level was also enhanced by SA treatment, indicating enhanced level of NO that also supports above mentioned hypothesis of SA mediated enhancement of NO leading to enhanced Fe availability and increase in photosynthetic pigments.

OsFRDL1, responsible for Fe efflux into xylem (Inoue et al., 2004), was down regulated in AsV stressed plants and this decrease was concomitant with reduced Fe accumulation in shoot. OsYSL2, responsible for long distance transport of Fe (Ishimaru et al., 2010), was enhanced in both SA, and AsV treated plants, however, no increase in Fe accumulation in shoot was observed. OsNRAMP5 is involved in uptake of Fe in root (Ishimaru et al., 2012). The expression of OsNRAMP5 was enhanced in both SA and AsV treated plants and an increase in Fe accumulation in root was observed as well.

Inside the cell As induces ROS synthesis that leads to oxidative stress (Finnegan and Chen, 2012). In present study oxidative stress is indicated by enhanced level of H2O2 and MDA content in AsV treated plant as reported earlier in rice (Tripathi et al., 2012). Disturbed redox homeostasis in response to AsV has been reported as the main factor for hampered growth of rice seedlings (Srivastava et al., 2014). SA treatment reduced the level of AsV induced H2O2 and MDA which indicates that SA protected the plant against AsV mediated oxidative stress. Similar protective effects of SA has been observed against Cd stress in rice (Guo et al., 2007) and barley (Metwally et al., 2003) and against As stress in Arabidopsis (Odjegba, 2012). SA mediated responses are associated with H2O2 accumulation (Drazic and Mihailovic, 2005). At moderate level, H2O2 serves as a secondary messenger for activation of stress resistance mechanism in plants (Noctor and Foyer, 1998). In present study SA application activated a slight accumulation of H2O2.

Ascorbate and glutathione (GSH/GSSG) are two important antioxidants. They are redox buffering agents in the apoplast and protect the plasma membrane from oxidation (Noctor and Foyer, 1998). The ratio of GSH/ GSSG is an important marker for oxidative stress (Tausz et al., 2004). The reduced GSH/ GSSG ratio in present study showed disturbed redox balance upon AsV exposure. Application of SA has enhanced the GSH/ GSSG ratio. Enhanced GSH/ GSSG ratio in response to SA has also been reported in cucumber seedlings (Shi and Zhu, 2008). The enhanced AsV tolerance upon thiourea application was suggested to be associated with TU ability to maintain plant redox homeostasis through improved GSH/GSSG ratio (Srivastava et al., 2014). Ascorbate is an effective scavenger for free radicals (Hasanuzzaman and Fujita, 2013). Co-application of SA and AsV also enhanced the level of Asc thus improving the redox balance under AsV stress. Similar results were observed in Alfa during mercury stress (Zhou et al., 2009). The increase in the level of GSH might be due to the fact that gene encoding glutathione-dependent formaldehyde dehydrogenase /GSNO reductase was activated by SA in Arabidopsis (Dıìaz et al., 2003).

In present study, under AsV stress the activity of antioxidant enzymes APX, GPX, SOD, and CAT were enhanced in dose dependent manner. These enzymes consume the H2O2 as substrate so with the enhancement of H2O2 concentration, activity of these enzymes also enhanced. SA has high affinity to CAT and APX thereby inhibits their activities (Vlot et al., 2009; Manohar et al., 2015). In the present study SA supplementation to AsV stressed plants reduced the APX and CAT activity than AsV alone treated plants. SA is believed to inhibit CAT by the chelation of heme Fe and by causing conformational changes (Rüffer et al., 1995). However, Durner and Klessig (1996) suggested that SA-mediated inhibition of CAT probably results from peroxidative reactions.

Guaiacol peroxidase exists in various isoenzyme forms in rice and has varied functions in plant metabolism but H2O2 serves as necessary substrate for their activity. Arsenate stress enhanced the GPX activity in dose dependent manner. SA enhanced the activity of GPX as previously reported in Medicago sativa (Zhou et al., 2009) and in rice (Guo et al., 2007).

In present study, no significant change was observed in endogenous level of SA under AsV stress that is in contrast to previous studies which reported enhancement in endogenous level of SA under abiotic stress (Miura and Tada, 2014). Since rice shoot has high level of endogenous SA among all the plants tested for SA (Silverman et al., 1995), therefore, under abiotic stress endogenous level of SA may not show any significant change. Similar results were found under biotic stress when little or no change was observed in endogenous level of SA, during bacterial or fungal infection (Silverman et al., 1995; Yang et al., 2004).

Conclusion

Taken together it is evident from present work that SA has reduced the AsV induced oxidative stress and effectively modulated the enzymatic and non-enzymatic antioxidants. SA also played a role in enhancing Asc, GSH, and PCs in plants subjected to AsV stress. SA reduced the As accumulation in shoot and also overcame the As induced Fe deficiency in shoot so the elaborated study of SA signaling may be helpful in developing the As resistant crops.

Author Contributions

RT, PT, VP, DC, Shekhar Mallick designed experiments and reviewed manuscript. AS, GD performed experimental work and prepared figures. MT Operated Thermocycler. Seema Mishra, SD reviewed manuscript. All authors have read and approved the manuscript.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors are thankful to Director, CSIR – National Botanical Research Institute (CSIR – NBRI), Lucknow for the facilities and for the financial support from the network projects (CSIR – INDEPTH), New Delhi, India. AS is thankful to University Grant Commission, New Delhi, India for the award of Junior/Senior Research Fellowship and Academy of Scientific and Innovative Research (AcSIR) for his Ph.D. registration.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: http://journal.frontiersin.org/article/10.3389/fpls.2015.00340/abstract

References

- Arnon D. I. (1949). Copper enzymes in isolated chloroplasts. Polyphenoloxidase in Beta vulgaris. Plant Physiol. 24 1–15 10.1104/pp.24.1.1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beauchamp C., Fridovich I. (1971). Superoxide dismutase: improved assays and an assay applicable to acrylamide gels. Anal. Biochem. 44 276–287 10.1016/0003-2697(71)90370-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dıìaz M., Achkor H., Titarenko E., Martıìnez M. C. (2003). The gene encoding glutathione-dependent formaldehyde dehydrogenase/GSNO reductase is responsive to wounding, jasmonic acid and salicylic acid. FEBS Lett. 543 136–139 10.1016/S0014-5793(03)00426-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drazic G., Mihailovic N. (2005). Modification of cadmium toxicity in soybean seedlings by salicylic acid. Plant Sci. 168 511–517 10.1016/j.plantsci.2004.09.019 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Duan G. L., Hu Y., Liu W. J., Kneer R., Zhao F. J., Zhu Y. G. (2011). Evidence for a role of phytochelatins in regulating arsenic accumulation in rice grain. Environ. Exp. Bot. 71 416–421 10.1016/j.envexpbot.2011.02.016 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Durner J., Klessig D. F. (1996). Salicylic acid is a modulator of tobacco and mammalian catalases. J. Biol. Chem. 271 28492–28501 10.1074/jbc.271.45.28492 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duxbury A. C., Yentsch C. S. (1956). Plankton pigment nomographs. J. Mar. Res. 15 92–101 10.1016/j.pestbp.2015.03.013u2.01 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Eichhorn H., Klinghammer M., Becht P., Tenhaken R. (2006). Isolation of a novel ABC-transporter gene from soybean induced by salicylic acid. J. Exp. Bot. 57 2193–2201 10.1093/jxb/erj179 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellman G. L. (1959). Tissue sulfhydryl groups. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 82 70–77 10.1016/0003-9861(59)90090-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finnegan P. M., Chen W. (2012). Arsenic toxicity: the effects on plant metabolism. Front. Physiol. 3:182 10.3389/fphys.2012.00182 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graziano M., Lamattina L. (2007). Nitric oxide accumulation is required for molecular and physiological responses to iron deficiency in tomato roots. Plant J. 52 949–960 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2007.03283.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gunes A., Inal A., Alpaslan M., Eraslan F., Bagci E. G., Cicek N. (2007). Salicylic acid induced changes on some physiological parameters symptomatic for oxidative stress and mineral nutrition in maize (Zea mays L.) grown under salinity. J. Plant Physiol. 164 728–736 10.1016/j.jplph.2005.12.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo B., Liang Y. C., Zhu Y. G., Zhao F. J. (2007). Role of salicylic acid in alleviating oxidative damage in rice roots (Oryza sativa) subjected to cadmium stress. Environ. Pollut. 147 743–749 10.1016/j.envpol.2006.09.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gutiérrez-Coronado M. A., Trejo-López C., Larqué-Saavedra A. (1998). Effects of salicylic acid on the growth of roots and shoots in soybean. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 36 563–565 10.1016/S0981-9428(98)80003-X [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hageman R. H., Reed A. J. (1980). Nitrate reductase from higher plants. Methods Enzymol. 69 270–280 10.1016/S0076-6879(80)69026-0 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hasanuzzaman M., Fujita M. (2013). Exogenous sodium nitroprusside alleviates arsenic-induced oxidative stress in wheat (Triticumaestivum L.) seedlings by enhancing antioxidant defense and glyoxalase system. Ecotoxicology 22 584–596 10.1007/s10646-013-1050-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heath R. L., Packer L. (1968). Photoperoxidation in isolated chloroplasts: I. Kinetics and stoichiometry of fatty acid peroxidation. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 125 189–198 10.1016/0003-9861(68)90654-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hissin P. J., Hilf R. (1976). A fluorometric method for determination of oxidized and reduced glutathione in tissues. Anal. Biochem. 74 214–226 10.1016/0003-2697(76)90326-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inoue H., Suzuki M., Takahashi M., Nakanishi H., Mori S., Nishizawa N. K. (2004). A rice FRD‘like (OsFRDL1) gene is expressed in the cells involved in long-distance transport. Soil Sci. Plant Nutr. 50 1133–1140 10.1080/00380768.2004.10408586 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ishimaru Y., Masuda H., Bashir K., Inoue H., Tsukamoto T., Takahashi M. (2010). Rice metal-nicotianamine transporter, OsYSL2 is required for the long-distance transport of iron and manganese. Plant J. 62 379–390 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2010.04158.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishimaru Y., Suzuki M., Tsukamoto T., Suzuki K., Nakazono M., Kobayashi T. (2006). Rice plants take up iron as an Fe3+ phytosiderophore and as Fe2+. Plant J. 45 335–346 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2005.02624.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishimaru Y., Takahashi R., Bashir K., Shimo H., Senoura T., Sugimoto K. (2012). Characterizing the role of rice NRAMP5 in manganese, iron and cadmium transport. Sci. Rep. 2 286 10.1038/srep00286 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang H. G., Singh K. B. (2000). Characterization of salicylic acid-responsive, Arabidopsis Dof domain proteins: over expression of OBP3 leads to growth defects. Plant J. 21 329–339 10.1046/j.1365-313x.2000.00678.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kato M., Shimizu S. (1987). Chlorophyll metabolism in higher plants. VII. Chlorophyll degradation in senescing tobacco leaves; phenolic-dependent peroxidative degradation. Can. J. Bot. 65 729–735 10.1139/b87-097 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Khodary S. E. A. (2004). Effect of salicylic acid on the growth, photosynthesis and carbohydrate metabolism in salt-stressed maize plants. Int. J. Agric. Biol. 6 5–8. [Google Scholar]

- Kobayashi T., Nishizawa N. K. (2012). Iron uptake, translocation and regulation in higher plants. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 63 131–152 10.1146/annurev-arplant-042811-105522 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kong J., Dong Y., Xu L., Liu S., Bai X. (2014). Effects of foliar application of salicylic acid and nitric oxide in alleviating iron deficiency induced chlorosis of Arachis hypogaea L. Bot. Stud. 55 9 10.1186/1999-3110-55-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar A., Dwivedi S., Singh R. P., Chakrabarty D., Mallick S., Trivedi P. K. (2014a). Evaluation of amino acid profile in contrasting arsenic accumulating rice genotypes under arsenic stress. Biol. Plant. 58 733–742 10.1007/s10535-014-0435-4 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar A., Singh R. P., Singh P. K., Awasthi S., Chakrabarty D., Trivedi P. K. (2014b). Selenium ameliorates arsenic induced oxidative stress through modulation of antioxidant enzymes and thiols in rice (Oryza sativa L). Ecotoxicology 23 1153–1163 10.1007/s10646-014-1257-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar S., Dubey R. S., Tripathi R. D., Chakrabarty D., Trivedi P. K. (2015). Omics and biotechnology of arsenic stress and detoxification in plants: current updates and prospective. Environ. Int. 74 221–230 10.1016/j.envint.2014.10.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Livak K. J., Schmittgen T. D. (2001). Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2 -ΔΔCT Method. Methods 2 402–408 10.1006/meth.2001.1262 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma J. F., Yamaji N., Mitani N., Xu X. Y., Su Y. H., McGrath S. P., et al. (2008). Transporters of arsenite in rice and their role in arsenic accumulation in rice grain. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 105 9931–9935 10.1073/pnas.0802361105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mallick S., Kumar N., Singh A. P., Sinam G., Yadav R. N., Sinha S. (2012). Role of sulfate in detoxification of arsenate induced toxicity in Zea mays L. (SRHM 445) nutrient status and antioxidants. J. Plant Interact. 8 140–154 10.1080/17429145.2012.734863 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Manohar M., Tian M., Moreau M., Park S. W., Choi H. W., Fei Z. (2015). Identification of multiple salicylic acid-binding proteins using two high throughput screens. Front. Plant Sci. 5:777 10.3389/fpls.2014.00777 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCarty K. M., Hanh H. T., Kim K. W. (2011). Arsenic geochemistry and human health in South East Asia. Rev. Environ. Health 26 71–78 10.1515/reveh.2011.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Metwally A., Finkemeier I., Georgi M., Dietz K. J. (2003). Salicylic acid alleviates the cadmium toxicity in barley seedlings. Plant Physiol. 132 272–281 10.1104/pp.102.018457 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mishra S., Stärk H. J., Küpper H. (2014). A different sequence of events than previously reported leads to arsenic-induced damage in Ceratophyllum demersum L. Metallomics 6 444–454 10.1039/c3mt00317e [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mishra S., Wellenreuther G., Mattusch J., Stärk H. J., Küpper H. (2013). Speciation and distribution of arsenic in the nonhyperaccumulator macrophyte Ceratophyllum demersum. Plant Physiol. 163 1396–1408 10.1104/pp.113.224303 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miura K., Tada Y. (2014). Regulation of water, salinity, and cold stress responses by salicylic acid. Front. Plant Sci. 5:4 10.3389/fpls.2014.00004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakano Y., Asada K. (1981). Hydrogen peroxide is scavenged by ascorbate-specific peroxidase in spinach chloroplasts. Plant Cell Physiol. 22 867–880. [Google Scholar]

- Noctor G., Foyer C. H. (1998). Ascorbate and glutathione: keeping active oxygen under control. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 49 249–279 10.1146/annurev.arplant.49.1.249 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noriega G., Caggiano E., Lecube M. L., Santa Cruz D., Batlle A., Tomaro M., et al. (2012). The role of salicylic acid in the prevention of oxidative stress elicited by cadmium in soybean plants. Biometals 25 1155–1165 10.1007/s10534-012-9577-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Odjegba V. J. (2012). Exogenous salicylic acid alleviates arsenic toxicity in Arabidopsis thaliana. Indian J. Inno. Dev. 1 515–522. [Google Scholar]

- Ogo Y., Itai R. N., Nakanishi H., Kobayashi T., Takahashi M., Mori S. (2007). The rice bHLH protein OsIRO2 is an essential regulator of the genes involved in Fe uptake under Fe-deficient conditions. Plant J. 51 366–377 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2007.03149.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pan X., Welti R., Wang X. (2010). Quantitative analysis of major plant hormones in crude plant extracts by high-performance liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry. Nat. Protoc. 5 986–992 10.1038/nprot.2010.37 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pickering I. J., Prince R. C., George M. J., Smith R. D., George G. N., Salt D. E. (2000). Reduction and coordination of arsenic in Indian mustard. Plant Physiol. 122 1171–1178 10.1104/pp.122.4.1171 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rahman M. A., Hasegawa H., Rahman M. M., Islam M. N., Miah M. A., Tasmen A. (2007). Effect of arsenic on photosynthesis, growth and yield of five widely cultivated rice (Oryzasativa L.) varieties in Bangladesh. Chemosphere 67 1072–1079 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2006.11.061 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Römheld V., Marschner H. (1986). Evidence for a specific uptake system for iron phytosiderophore in roots of grasses. Plant Physiol. 80 175–180 10.1104/pp.80.1.175 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rüffer M., Steipe B., Zenk M. H. (1995). Evidence against specific binding of salicylic acid to plant catalase. FEBS Lett. 377 175–180 10.1016/0014-5793(95)01334-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scandalios J. G., Tsaftaris A. S., Chandlee J. M., Skadsen R. W. (1983). Expression of the developmentally regulated catalase (Cat) genes in maize. Dev. Genet. 4 281–293 10.1002/dvg.1020040406 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shakirova F., Sakhabudinova A., Bezrukova M. K., Fathutdinova M. D. (2003). Changes in the hormonal status of wheat seedlings induced by salicylic acid and salinity. Plant Sci. 164 317–322 10.1016/S0168-9452(02)00415-6 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shi Q., Zhu Z. (2008). Effects of exogenous salicylic acid on manganese toxicity, element contents and antioxidative system in cucumber. Environ. Exp. Bot. 63 317–326 10.1016/j.envexpbot.2007.11.003 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shukla V. K. S., Kokate C. K., Srivastava K. C. (1979). Spectrophotometric determination of ascorbic acid. Microchem. J. 24 124–126 10.1016/0026-265X(79)90048-1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Silverman P., Seskar M., Kanter D., Schweizer P., Metraux J. P., Raskin I. (1995). Salicylic acid in rice (biosynthesis, conjugation, and possible role). Plant Physiol. 108 633–639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song W. Y., Park J., Mendoza-Cózatl D. G., Suter-Grotemeyer M., Shim D., Hörtensteiner S. (2010). Arsenic tolerance in Arabidopsis is mediated by two ABCC-type phytochelatin transporters. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 107 21187–21192 10.1073/pnas.1013964107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Srivastava A. K., Srivastava S., Mishra S., D’Souza S. F., Suprasanna P. (2014). Identification of redox-regulated components of arsenate (As V) tolerance through thiourea supplementation in rice. Metallomics 6 1718–1730 10.1039/C4MT00039K [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szalai G., Krantev A., Yordanova R., Popova L. P., Janda T. (2013). Influence of salicylic acid on phytochelatin synthesis in Zea mays during Cd stress. Turk. J. Bot. 37 708–714. [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi Y., Minamikawa R., Hattori K. H., Kurishima K., Kihou N., Yuita K. (2004). Arsenic behaviour in paddy fields during the cycle of flooded and non-flooded periods. Environ. Sci. Technol. 38 1038–1044 10.1021/es034383n [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tausz M., Šircelj H., Grill D. (2004). The glutathione system as a stress marker in plant ecophysiology: is a stress-response concept valid? J. Exp. Bot. 55 1955–1962 10.1093/jxb/erh194 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tripathi P., Mishra A., Dwivedi S., Chakrabarty D., Trivedi P. K., Singh R. P. (2012). Differential response of oxidative stress and thiol metabolism in contrasting rice genotypes for arsenic tolerance. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 79 189–198 10.1016/j.ecoenv.2011.12.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tripathi R. D., Srivastava S., Mishra S., Singh N., Tuli R., Gupta D. K. (2007). Arsenic hazards: strategies for tolerance and remediation by plants. Trends Biotechnol. 25 158–165 10.1016/j.tibtech.2007.02.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Velikova V., Yordanov I., Edreva A. (2000). Oxidative stress and some antioxidant systems in acid rain-treated bean plants: protective role of exogenous polyamines. Plant Sci. 151 59–66 10.1016/S0168-9452(99)00197-1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Vlot A. C., Dempsey D. M. A., Klessing D. (2009). Salicylic acid, a multifaceted hormone to combat disease. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 47 177–206 10.1146/annurev.phyto.050908.135202 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Y., Qi M., Mei C. (2004). Endogenous salicylic acid protects rice plants from oxidative damage caused by aging as well as biotic and abiotic stress. Plant J. 40 909–919 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2004.02267.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yokosho K., Yamaji N., Ueno D., Mitani N., Ma J. F. (2009). OsFRDL1 is a citrate transporter required for efficient translocation of iron in rice. Plant Physiol. 149 297–305 10.1104/pp.108.128132 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan S., Lin S. S. (2008). Role of salicylic acid in plant abiotic stress. Z. Naturforsch. C 63 313–320 10.1515/znc-2008-5-601 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yusuf M., Fariduddin Q., Varshney P., Ahmad A. (2012). Salicylic acid minimizes nickel and/or salinity-induced toxicity in Indian mustard (Brassica juncea) through an improved antioxidant system. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. Int. 19 8–18 10.1007/s11356-011-0531-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou Z. S., Guo K., Elbaz A. A., Yang Z. M. (2009). Salicylic acid alleviates mercury toxicity by preventing oxidative stress in roots of Medicago sativa. Environ. Exp. Bot. 65 27–34 10.1016/j.envexpbot.2008.06.001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zottini M., Costa A., De Michele R., Ruzzene M., Carimi F., Schiavo F. L. (2007). Salicylic acid activates nitric oxide synthesis in Arabidopsis. J. Exp. Bot. 58 1397–1405 10.1093/jxb/erm001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.