Abstract

The importance of microbial activity to ecosystem function in aquatic ecosystems is well established, but microbial diversity has been less frequently addressed. This review and synthesis of 100s of published studies on stream microbial diversity shows that factors known to drive ecosystem processes, such as nutrient availability, hydrology, metal contamination, contrasting land-use and temperature, also cause heterogeneity in bacterial diversity. Temporal heterogeneity in stream bacterial diversity was frequently observed, reflecting the dynamic nature of both stream ecosystems and microbial community composition. However, within-stream spatial differences in stream bacterial diversity were more commonly observed, driven specifically by different organic matter (OM) compartments. Bacterial phyla showed similar patterns in relative abundance with regard to compartment type across different streams. For example, surface water contained the highest relative abundance of Actinobacteria, while epilithon contained the highest relative abundance of Cyanobacteria and Bacteroidetes. This suggests that contrasting physical and/or nutritional habitats characterized by different stream OM compartment types may select for certain bacterial lineages. When comparing the prevalence of physicochemical effects on stream bacterial diversity, effects of changing metal concentrations were most, while effects of differences in nutrient concentrations were least frequently observed. This may indicate that although changing nutrient concentrations do tend to affect microbial diversity, other environmental factors are more likely to alter stream microbial diversity and function. The common observation of connections between ecosystem process drivers and microbial diversity suggests that microbial taxonomic turnover could mediate ecosystem-scale responses to changing environmental conditions, including both microbial habitat distribution and physicochemical factors.

Keywords: ecosystem structure and function, lotic ecosystems, microbial diversity, rivers, streams

Introduction

Aquatic microbial diversity is well understood to be a key component of aquatic ecosystem functioning (Nold and Zwart, 1998; Cotner and Biddanda, 2002; Gessner et al., 2010), and major advances toward linking microbial diversity with ecosystem function have been made in aquatic systems (Horner-Devine et al., 2003; Smith, 2007; Singer et al., 2010; Comte et al., 2013). While the responsiveness of microbial diversity to environmental variability is an ongoing topic of inquiry (Finlay, 2002; Allison and Martiny, 2008; Langenheder et al., 2012; Shade et al., 2012), it is clear that global environmental change poses many potential threats to the structure and function of all aquatic ecosystems (Malmqvist and Rundle, 2002; Dudgeon et al., 2006), and that changing environmental factors at the watershed scale directly impact the biological function of lotic ecosystems (Likens et al., 1970; Hynes, 1975; Mulholland et al., 2008; Palmer and Febria, 2012). However, a recent survey of microbial diversity studies in aquatic habitats showed that microbial diversity in lotic environments is less commonly studied than in marine and lake ecosystems, and that impacted systems are less commonly studied than unimpacted systems (Zinger et al., 2012). Given the importance of microbial processes to lotic ecosystem function, and the microbial genetic diversity that contains the information supporting those functions as well as the potential for resilience under environmental changes, it is critical to study stream microbial diversity in the context of shifting environmental drivers.

Streams and rivers are hotspots of microbially mediated carbon (C) and nutrient processing within landscapes (Hynes, 1975; Fisher et al., 1998; McClain et al., 2003). Microbial activity drives organic matter (OM) decomposition, whole-stream respiration and C flow to higher trophic levels (Lindeman, 1942; Meyer, 1994; Hall and Meyer, 1998; Hieber and Gessner, 2002; Tank et al., 2010). Thus, microbial processes are at the center of the conceptual model of OM processing and food web structure through the river continuum (Vannote et al., 1980; Minshall et al., 1985). Also, microbial nitrification, denitrification, and heterotrophic nitrogen (N) uptake in small streams affects downstream water quality (Peterson et al., 2001; Mulholland et al., 2008; Valett et al., 2008). There is a strong history and impact of studying microbial processes within and among stream and river ecosystems, yet molecular methods, which enable the study of microbial diversity within the context of ecosystem function, have not been widely utilized in lotic ecosystems (Findlay, 2010).

Studies on bacterial and fungal diversity in lotic ecosystems have been historically more associated with the research themes of microbial transport and leaf litter decomposition, respectively. Stream fungal diversity research has traditionally been rooted in an ecological context, investigating the patterns and mechanisms of aquatic hypomycete succession that occur on leaf biofilms concomitant with the progression of leaf decomposition (Suberkropp and Klug, 1976; Suberkropp et al., 1976; Webster and Descals, 1981; Bärlocher, 1982; Gessner et al., 1993). Early stream bacterial diversity research consisted of culture-for-diversity assessments of bacterial loads in the water column, resulting in predominantly Pseudomonas sp. isolates with variation in diversity correlated most strongly with water temperature, storm events and sunshine (Bell et al., 1982a,b). These studies relied upon microscopy for identification of fungal conidia following sporulation or substrate utilization profiling of bacterial isolates. Bacterial diversity was particularly difficult to define, beyond differentiating gram-negative from gram-positive cells (Geesey et al., 1977) or conducting plate counts on selective media (Milner and Goulder, 1984), before the availability of molecular tools.

The application of molecular techniques to measure stream microbial diversity produced new insights. Genetic markers within each “Pseudomonas” sp. isolate differed among isolates derived from the same stream, and between stream- and soil-derived isolates (McArthur et al., 1992); somewhat analogously, the distribution of selected loci differed among Tetrachaetum elegans monosporic isolates from different leaf species within the same stream (Charcosset and Gardes, 1999). Also, the genetic composition of the entire microbiota found on fine particulate OM was more similar than expected given differences in water chemistry among the streams sampled (Sinsabaugh et al., 1992). Following the establishment of the ribosomal rRNA gene as a conserved marker of taxonomic lineage (Pace, 1997), studies on water column biota began to resolve longitudinal patterns in microbial diversity (Crump et al., 1999; Crump and Baross, 2000), and efforts to integrate molecular and traditional tools in studies of fungal diversity were mounted (Nikolcheva et al., 2003; Nikolcheva and Bärlocher, 2005). In the 21st century, studies of molecular microbial diversity in lotic ecosystems are increasing to an extent that a review and synthesis of progress on the topic is needed.

Because microbial processes in stream and river ecosystems are variable in space and time in response to differences in nutrient availability (Dodds et al., 2000), temperature (Boyero et al., 2011), OM quality or quantity (Gessner and Chauvet, 1994), hydrological factors (Valett et al., 1997), or land use (Mulholland et al., 2008), a reasonable initial prediction is that microbial diversity might also respond to changes in these environmental variables. In fact, many recent studies of molecular microbial diversity in streams have been initiated based on this rationale. Among these case studies, there are many examples of variation in microbial diversity in response to environmental variability, many examples of microbial diversity showing no response to the predicted driver, and many examples of microbial diversity changing with one environmental factor, but not another, in the same study. This leads to a large degree of uncertainty in the extent to which lotic microbiota are sensitive or resistant to environmental perturbation (Allison and Martiny, 2008; Shade et al., 2012). If microbial functions are phylogentically conserved to any extent, there should be some predictability to the changes in microbial diversity along environmental gradients in space and time (Phillippot et al., 2010). If functional redundancy among microbial taxa or physiological flexibility due to functional diversity within microbial taxa is high, microbial diversity will be more static in the face of environmental fluctuation. One literature review cannot tease apart these complex mechanisms; however, it can attempt to identify which environmental factors are demonstrated to be more or less likely to affect microbial diversity. Any pattern can inform hypotheses regarding the sensitivity or resilience of diverse aquatic microbiota to the multiple categories of current environmental threats to aquatic ecosystems (Malmqvist and Rundle, 2002).

With this goal in mind, I gathered published papers on microbial diversity in streams and rivers for a focused review. After collecting papers, I recorded the findings of each in a categorical manner: I noted the significance or lack thereof for each comparison within each study, differentiated among the effects of defined environmental drivers and contrasting levels of spatiotemporal variation, tallied the frequency of studies using various methodologies, and harvested coarse taxonomic data from relevant studies. The result is a synthesis that is a step beyond a traditional review, but not as quantitatively rigorous as a true meta-analysis. There was a great deal of evidence for sensitivity of lotic microbial communities to environmental variation, and somewhat surprising implications regarding the relative influence of physical versus geochemical factors on microbial diversity.

Methods

To collect as many published, peer-reviewed studies on stream microbial diversity as possible, I searched the Web of Science database using the parameters TS = (“stream” OR “river” OR “lotic”) AND TS = (microb∗ OR bacteria∗ OR fung∗) AND TS = “diversity” for all full years available (through 2013). I screened search results and kept all papers that (i) reported microbial taxonomic diversity including data collected using molecular, microscopy, and “culture for diversity” methods and (ii) evaluated the effect of some environmental variable on microbial diversity. I accepted papers that reported diversity as richness, as a diversity index incorporating some estimate of relative abundance of taxa, or as the relative abundance of measured taxa (community structure). These search parameters may not catch some relevant studies, however, the resulting synthesis of 294 papers is to my knowledge the most comprehensive to date.

These studies were categorized based on (i) the microbial group of interest (fungi, bacteria, protozoa, archaea, stramenopiles); (ii) the methodology used (microscopy, denaturing gradient gel electrophoresis (DGGE), terminal restriction fragment length polymorphism (T-RFLP), sequencing of genes from clone libraries, sequencing of genes from next-generation technology libraries, fluorescent in situ hybridization (FISH), other molecular methods and other non-molecular methods; and (iii) the environmental driver(s) evaluated by the study (temporal variation, among-stream variation, longitudinal variation, differences in nutrient concentrations, differences in OM quantity or quality, OM compartment type, hydrologic variation, differences in metals concentrations, differences in surrounding land-use, and differences in temperature, Table 1). All studies were also categorized by the OM compartment sampled coarse particular organic matter (CPOM, leaves or wood), water column, epilithon (biofilm attached to any hard surface), streambed sediment, hyporheic biofilm or water, and other [including, e.g., foam, fine benthic organic matter (FBOM)], and by the scale of investigation (within-stream comparison, among-stream comparison, or among-region comparison). Many studies included multiple experiments or comparisons, or comparisons that could be classified under multiple categories (e.g., a study evaluating the effect of a wastewater treatment plant on bacterioplankton diversity was categorized as a longitudinal comparison and as a comparison of nutrient concentration effects).

Table 1.

Categories of environmental variation evaluated for effects on stream microbial diversity.

| Category | Definition/Variables included |

|---|---|

| Spatiotemporal variation | |

| Temporal variation (n = 101) | Samples collected at multiple time points |

| Among-stream variation (n = 82) | Samples collected at different streams |

| Longitudinal variation (n = 70) | Samples collected at different sites from up-to-downstream |

| Compartment type (n = 38) | At one site within a stream, samples collected from different OM/surface types (including rocks, coarse particular organic matter (CPOM), benthic surface sediment, subsurface sediment, or no surface i.e., water column) |

| Variation in defined environmental drivers | |

| Nutrient concentrations (n = 56) | Variation in surface water nutrient concentrations; nutrient = any form of N or P, or C:N, C:P, or N:P stoichiometry |

| Organic matter (OM) quality/quantity (n = 52) | Variation in surface water DOC concentrations, particulate OM stock, or substrate quality (e.g., different species of leaf litter) |

| Hydrological variation (n = 32) | Variation in stream flow, hydrological regime, or before/after a defined flooding or drying event |

| Metals effects (n = 31) | Variation in soluble metals concentrations (e.g., Al, Cd, Cu, Fe, Mn, Pb, Zn), or generalized acid mine drainage effects |

| Land-use (n = 28) | Variation in riparian or watershed land-use (e.g., agricultural, urban, undeveloped) |

| Temperature (n = 23) | Variation in water temperature |

Studies were classified into categories of spatiotemporal variation or variation in environmental drivers based on the sampling strategy employed in each study, with number (n) of studies noted for each category.

It is not valid to compare the values of derived diversity metrics or the abundance of microorganisms based on data collected with different methodologies and taxonomic resolutions, so a fully quantitative metaanalysis, using a response index, was not possible. However, it is valid to accept significant results of a study as informative, no matter the data type. For example, a meta-analysis of heterogeneity in soil microbial communities showed greater-than-random spatial similarity no matter the technique used to measure diversity, but the magnitude of heterogeneity detected was greater if a lower-resolution taxonomic definition was utilized (Horner-Devine et al., 2007). Therefore, for this study, a qualitative comparative approach was used: Each comparison of environmental variability on stream microbial diversity was categorized as “significant” or “non-significant,” based on the criteria used in the publication, and the distribution of significant results was compared among all studies. With this approach, a semi-quantitative evaluation of the most and least commonly observed effects of environmental drivers on stream microbial diversity was possible.

Some studies in the database reported the 16S rRNA gene sequence abundance of microbial taxa. While individual datasets had varied sequencing depths, particularly the clone library versus next-generation sequencing studies, the most abundant microbial populations should be the most commonly sequenced using any method. In the interest of extracting as much information as possible from the database, I harvested relative abundances of dominant phyla and subphyla in bacterial 16S rRNA gene libraries from the 29 studies that reported relative abundance in addition to diversity/heterogeneity summary metrics. This data extraction included neither studies that reported sequence information for only a subset of sequences gathered (thus skewing relative abundances higher), nor FISH data, which, while based on the 16S rRNA gene sequence, tend to not quantify bacterial phyla such as Acidobacteria, Cyanobacteria, or Verrucomicrobia. While differences in extraction protocol, sequencing primers, sequencing depth, and other technical particulars introduce potentially large sources of non-environmental variation to this analysis, signals that rise above the noise must be particularly strong. I tested the hypothesis that OM compartment type affected bacterial community composition across studies with a one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) and Bonferonni post hoc comparisons using R Commander (Fox, 2005; R Core Development Team, 2010).

Results

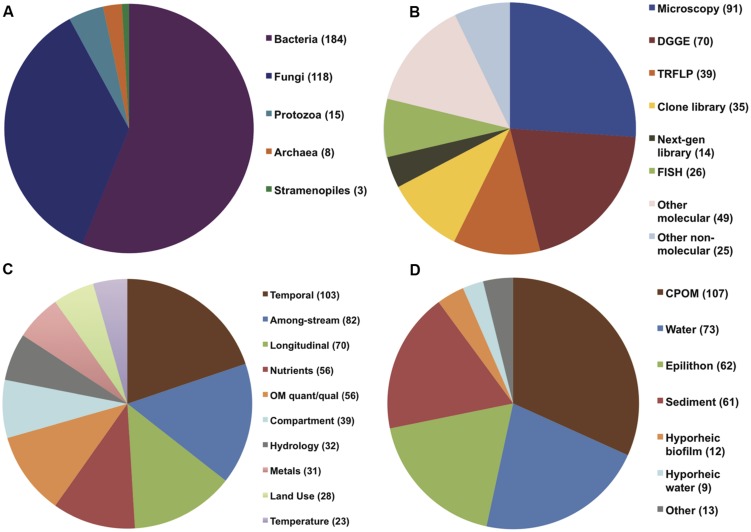

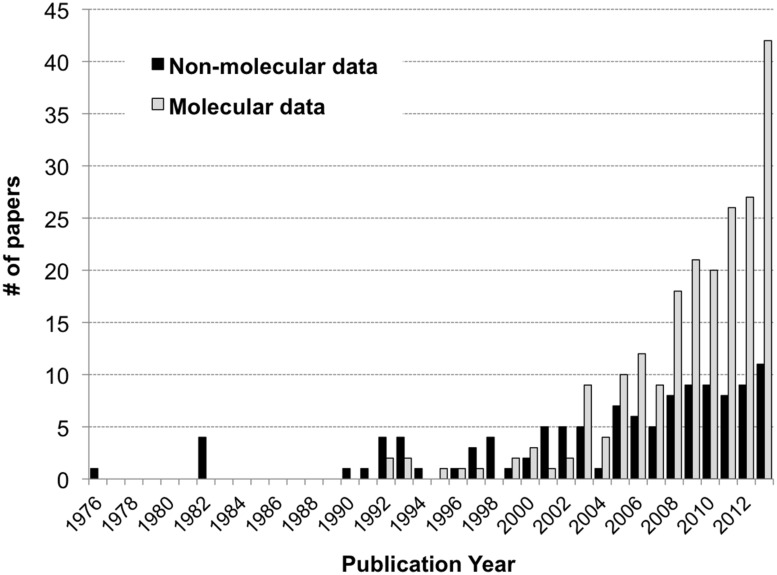

A total of 294 papers published between 1976 and 2013 were included in the analysis; these papers contained 520 comparisons of the effects of spatiotemporal heterogeneity or defined environmental drivers on microbial community composition in streams (Appendix). The majority of papers examined bacterial communities (56%), many examined fungal communities (36%), and the remainder examined archaeal, protozoan, or stramenopile communities (Figure 1). Many fungal studies utilized a definition of taxonomic identity based on conidial morphology, making microscopy the most common methodology in the database (26% of studies), followed by the “community fingerprint” techniques of DGGE and T-RFLP (20 and 11% of studies, respectively) and sequencing of ribosomal genes from clone libraries (10%; Figure 1). Only 4% of studies utilized next-generation sequencing, all published in 2012 or 2013; this reflects a more rapid increase in papers using molecular methods in the past decade (Figure 2). In total, almost half of the comparisons measured spatiotemporal variation in microbial community composition (temporal, 20%; among-stream, 16%; longitudinal, 14%), and the most commonly evaluated environmental drivers were nutrient concentration (11%) and OM quality or quantity (11%; Figure 1). Finally, among compartment types studied, CPOM was best represented (32%, primarily fungal communities), followed by the water column (22%, primarily bacterioplankton), epilithic biofilms (18%), and benthic sediment (18%; Figure 1).

FIGURE 1.

Pie charts showing distribution of (A) organism of study, (B) methodology used in study, (C) environmental drivers, and (D) compartment of study among all papers (294) included in the analysis.

FIGURE 2.

Histogram of the number of papers reporting stream microbial diversity from 1992 to 2013: papers using molecular methods as gray bars, non-molecular methods as black bars.

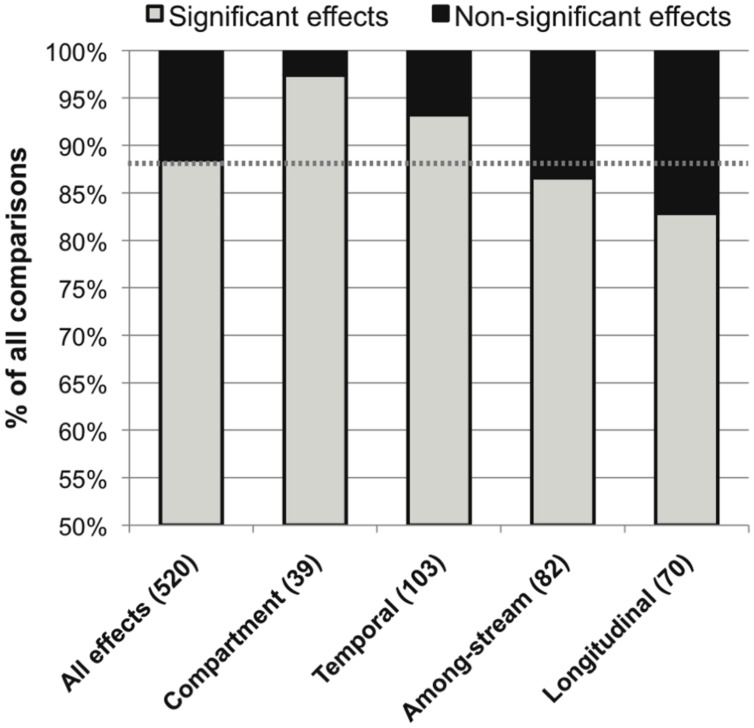

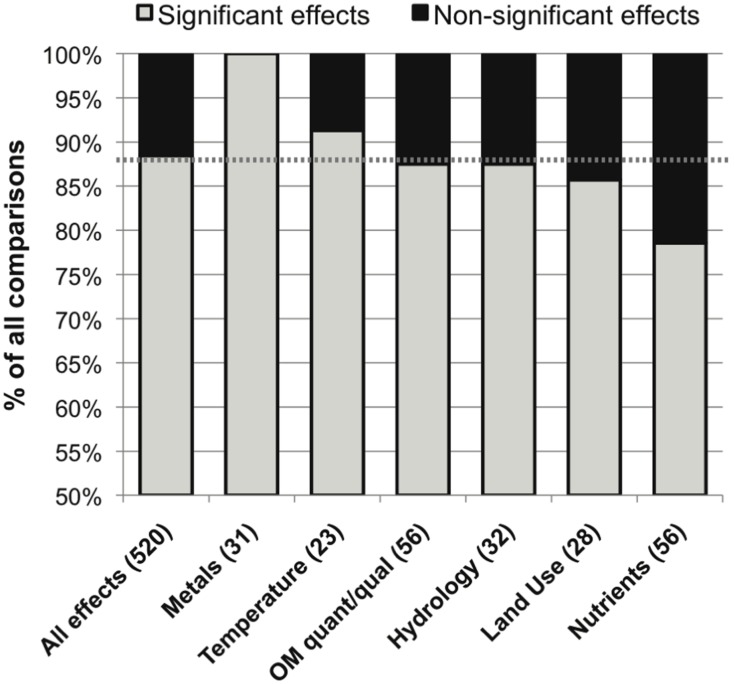

The overall distribution of published significant versus non-significant effects of environmental variation on stream microbial community composition was 88.5% versus 11.5%. The most common source of spatio-temporal heterogeneity was within-stream heterogeneity among different OM compartments (97% significance among published effects), followed by within-stream temporal, among-stream, and within-stream longitudinal heterogeneity (93, 87, and 83% significant effects, respectively; Figure 3).

FIGURE 3.

Distribution of significant (in gray) and non-significant (in black) reported effects of categories of spatiotemporal variation on stream microbial diversity, with number of included studies noted for each category along the x-axis, and the percentage of significant effects for all comparisons combined noted as a dashed line for reference.

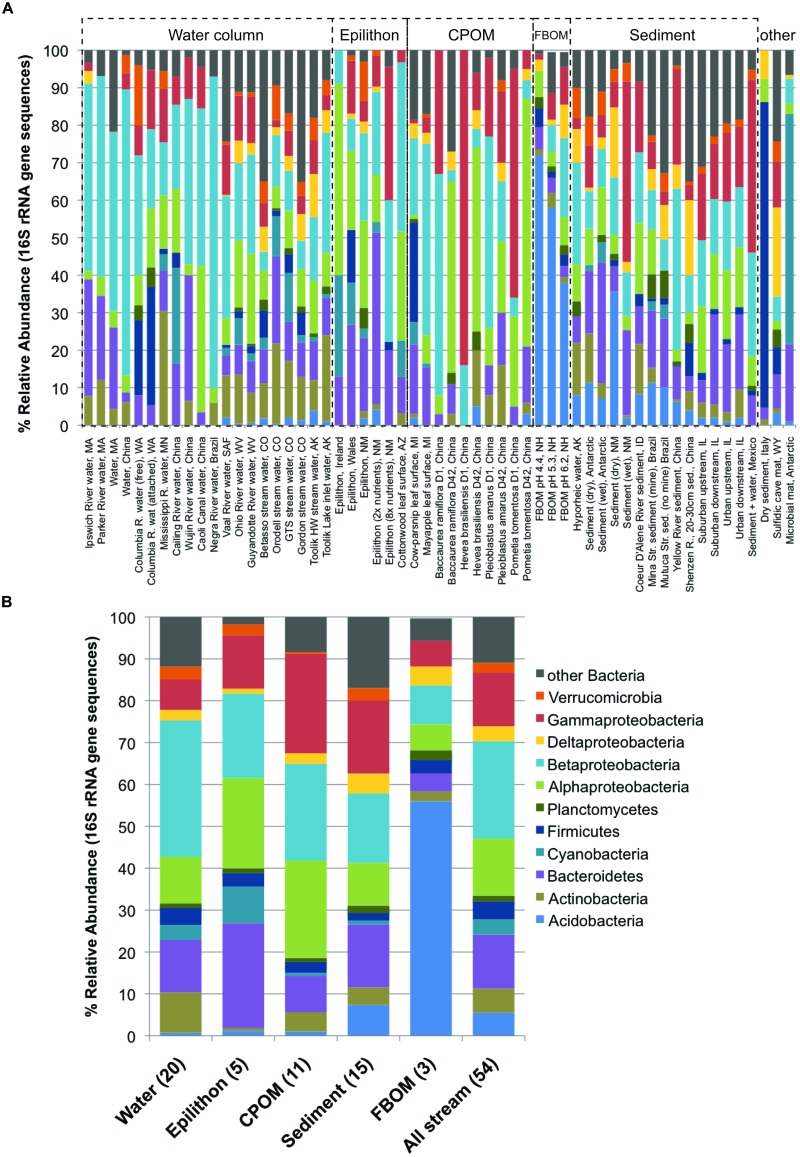

Because a good number of studies reported the dominant bacterial phyla and subphyla in 16S rRNA gene sequence libraries from defined sample types (either clone libraries, 21 studies; or next-generation sequencing, eight studies), it was possible to evaluate which taxonomic groups varied in relative abundance among compartments (Figure 4). The results of ANOVA post hoc comparisons showed significant among-compartment differentiation in a number of phyla, including the Acidobacteria, Actinobacteria, Bacteroidetes, Cyanobacteria, and other Bacteria (Table 2). Among different stream compartments, water column samples contained the highest relative abundance of Actinobacteria, epilithon samples contained the highest relative abundance of Bacteroidetes and Cyanobacteria, FBOM samples contained the highest relative abundance of Acidobacteria, and sediment samples contained the second highest relative abundance of Acidobacteria and the highest relative abundance of other Bacterial sequences.

FIGURE 4.

Relative abundance of major bacterial phyla and subphyla (based on 16S rRNA gene sequence libraries, available from 29 papers) for all available defined compartments: (A) all samples with habitats and locations noted along the x-axis and compartment type bracketed by dashed lines, noted above each group; (B) average community composition for each compartment.

Table 2.

Relative abundance [%, (1 SE)] of bacterial phyla and subphyla (rows) in stream compartments (columns) including analysis of variance (ANOVA) results for among-compartment comparisons: omnibus results in first column, and significant multiple comparisons groups (Bonferonni post hoc test, α = 0.05) in lower case superscripts (a-d).

| ANOVA results (F, P) | Water column | Epilithon | CPOM | Fine benthic organic matter (FBOM) | Sediment | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acidobacteria | 60.9, <0.0001 |

0.69a (0.24) |

1.20ab (0.82) |

0.91ab (0.51) |

56.0d (9.9) |

7.40c (2.2) |

| Actinobacteria | 3.15, 0.022 |

9.70b (1.8) |

0.65a (0.40) |

4.48ab (1.8) |

2.33ab (1.3) |

4.81ab (0.83) |

| Bacteroidetes | 4.02, 0.007 |

12.5a (9.3) |

25.0b (13) |

8.79a (6.4) |

4.33a (1.5) |

14.5ab (8.1) |

| Cyanobacteria | 2.46, 0.058 |

3.57ab (1.4) |

8.69b (5.6) |

3.25ab (0.98) |

0.00a (0) |

0.88ab (0.44) |

| Firmicutes | 0.319, 0.864 |

4.09 (1.8) |

3.27 (2.7) |

2.41 (2.4) |

3.17 (1.0) |

1.68 (0.58) |

| Planctomycetes | 0.852, 0.499 |

1.03 (0.34) |

1.10 (1.1) |

0.82 (0.50) |

2.33 (0.44) |

1.91 (0.65) |

| Alphaproteobacteria | 2.74, 0.039 |

11.1 (2.0) |

21.6 (8.4) |

23.8 (6.8) |

6.17 (1.1) |

10.2 (1.6) |

| Betaproteobacteria | 2.26, 0.076 |

32.6 (2.7) |

20.2 (5.4) |

25.2 (6.6) |

9.33 (6.2) |

17.3 (2.4) |

| Deltaproteobacteria | 1.27, 0.296 |

2.50 (0.51) |

1.17 (0.57) |

2.27 (0.69) |

4.50 (2.3) |

5.04 (1.7) |

| Gammaproteobacteria | 1.96, 0.115 |

7.26 (1.1) |

12.7 (6.2) |

21.9 (8.3) |

6.17 (2.5) |

16.5 (3.6) |

| Verrucomicrobia | 2.10, 0.095 |

3.07 (0.92) |

2.64 (1.97) |

0.36 (0.28) |

0.00 (0) |

3.30 (0.64) |

| Other bacteria | 3.03, 0.026 |

11.9ab (2.3) |

1.78a (0.87) |

7.59ab (2.8) |

5.33ab (3.0) |

16.5b (2.8) |

The category of defined environmental drivers with the most commonly significant effect was metals (100%), followed by temperature, OM quantity or quality and hydrology, land use and nutrient concentrations (91, 88, 88, 86 and 79% significant effects, respectively; Figure 5). The studies evaluating metals effects did not report widely comparable taxonomic data (these included a mix of fungal microscopic, fungal sequencing, bacterial sequencing, and non-sequencing data), so it was not possible to perform an evaluation of metals effects on microbial community composition.

FIGURE 5.

Distribution of significant (in gray) and non-significant (in black) reported effects of categories of variation in defined environmental drivers on stream microbial diversity, with number of included studies noted for each category along the x-axis, and the percentage of significant effects for all comparisons combined noted as a dashed line for reference.

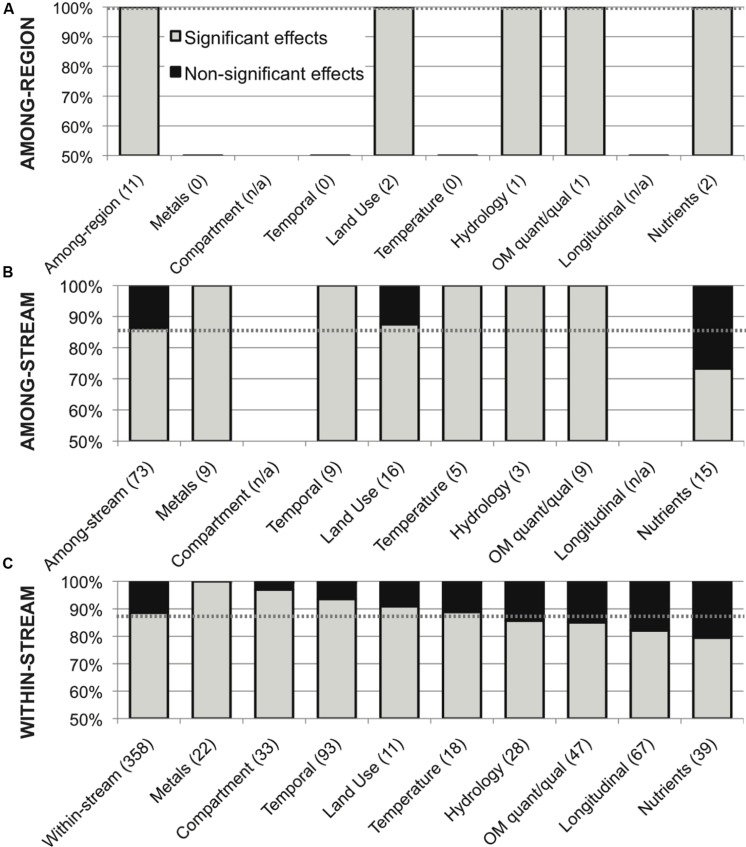

This meta-analysis of environmental variation in stream microbial diversity was dominated by within-stream studies (358 comparisons, 88.5% significant); to contrast with other study scales, the 73 among-stream comparisons showed a total distribution of 86% significant effects, with 100% significance within all categories of variation except land use and nutrient concentrations (88 and 73% significant effects, respectively), and the 11 among-region comparisons showed 100% significance within all categories of variation (Figure 6).

FIGURE 6.

Distribution of significant (in gray) and non-significant (in black) reported effects of categories of variation in all environmental drivers on stream microbial diversity, for (A) among-region comparisons, (B) among-stream comparisons and (C) within-stream comparisons; with number of included studies noted for each category along the x-axis, and the percentage of significant effects for all comparisons combined noted as a dashed line for reference, for each scale.

Discussion

The results of this data synthesis reflected a high incidence of microbial diversity responses to environmental variation in stream and river ecosystems. Among spatiotemporal factors, within-stream compartment differences and temporal differences were most common, while longitundinal differences were least common. Among defined drivers, “metals” effects were ubiquitous and land-use and nutrients effects were least common. Overall, lotic microbial communities are quite sensitive to environmental changes, but their functional redundancy may be greater in relation to certain environmental variables than others.

The relative distribution of significant and non-significant effects of different categories of environmental drivers on lotic microbial diversity provides an informative synthesis of the current state of the literature. However, the high number of significant comparisons – 88.5% – raises some concern of a literature bias favoring the publication of significant results. This is an established concern in the interpretation of metaanalyses, and can result from a lack of enthusiasm by authors or reviewers to publish a study with “no effect” (Rosenthal, 1979; Hedges, 1992). This phenomenon may occur to some extent, which is unfortunate since non-significant results are important information within the context of the broader state of knowledge on a subject, as this synthesis demonstrates. On the other hand, investigators form an hypothesis based on a justified rationale; in this case, the expectation that an environmental factor known to affect microbial processes might also affect microbial diversity (Allison and Martiny, 2008). The high prevalence of significant variation in lotic microbial diversity in response to all evaluated drivers is most likely a consequence of widespread microbial sensitivity to environmental change (Shade et al., 2012).

Spatiotemporal Heterogeneity

Microbes may be particularly sensitive to changes in their environment due to their small size and rapid growth rates. This high microbial turnover potential is reflected as a higher prevalence of temporal variation (93%) than longitudinal (83%) or among-stream (86%) variation in lotic microbiota (Figures 3 and 6). This temporal variation includes seasonal changes (Feris et al., 2003b; Olapade and Leff, 2004; Crump and Hobbie, 2005; Hullar et al., 2006), successional turnover on the order of days to weeks (Gessner et al., 1993; Lyautey et al., 2005; Wey et al., 2012; Wymore et al., 2013), and shifts with transient or less predictable durations directly associated with hydrological fluctuations (Battin et al., 2001; Rees et al., 2006; Chiaramonte et al., 2013; Fazi et al., 2013). These temporal changes can be correlated with multiple defined environmental drivers: Most notably, seasonal changes in water temperature, hydrology, OM quality and nutrient availability can be relatively predictable, and seasonal synchrony among years and streams in lotic bacterioplankton, epilithon, and sediment microbial diversity has been documented (Sutton and Findlay, 2003; Hullar et al., 2006; Crump et al., 2009). This is intriguing since it suggests that microbial community composition could be predictable based on environmental factors, as has been shown in lakes, estuaries, and oceans (Fuhrman et al., 2006; Ladau et al., 2013). However, predictability could be particularly challenging in stream and river ecosystems due to their variable hydrology and associated potential for cell dispersal via microbial transport (Bell et al., 1982a; Crump et al., 2012). Compared to other aquatic ecosystems, soils, and several other broad habitat types, stream ecosystems have the highest measured indices of temporal variability in microbial community composition (Portillo et al., 2012; Shade et al., 2013). Stream and river ecosystems, and their macrofauna, are characterized by temporal variability (Poff and Ward, 1989), and a high level of temporal turnover in microbial community composition may also be characteristic of lotic systems.

An even stronger and perhaps more surprising result was the widespread effect of compartment type on microbial diversity (Figure 3). Differences in stream microbiota between surface water, rock surfaces, leaves and wood, and streambed sediment – within the same stream – were more common than any other spatiotemporal effect. Only one study found similar microbial diversity between compartment types; this study took place in a contaminated stream where the high metals concentrations were hypothesized to limit fungal diversity (Sridhar et al., 2008). Bacterial community composition was remarkably consistent within compartment types in samples collected from a wide range of sites (Figure 4). The high relative abundance of Cyanobacteria and Bacteroidetes in epilithic biofilm makes sense, as autotrophic microbes such as Cyanobacteria are more competitive on an inorganic substrate, and Bacteroidetes are known to be characteristic of well-developed stream biofilms (Besemer et al., 2009). Stream and river sediments might contain more pore-scale heterogeneity and anaerobic microsites (Kemp and Dodds, 2001) that promote a greater abundance of narrower phyla or unknown taxa. It is less clear why Actinobacteria might be characteristic of surface waters or Acidobacteria might be characteristic of FBOM. This result does suggest, however, that characteristics of the within-stream physicochemical environment could select for specific groups of microorganisms, and that some physiological characteristics allowing successful colonization of different microbial habitats may be conserved at the phylum level (Phillippot et al., 2010).

The major physicochemical differences among lotic “microbial habitat” compartments are primarily OM type, which could select for microbes best suited to different categories of C processing, and surface type, which could select for microbes best suited to attachment and growth under certain conditions. The CPOM habitat consists of primarily complex polymeric OM, lignin, cellulose and lignocellulose, which can select for microbes that produce extracellular enzymes with oxidative and hydrolytic capabilities, such as fungi. Fine particulate OM habitat contains fragmented and processed OM with more surface area for bacterial colonization (Sinsabaugh et al., 1992). The sediment habitat may be the most heterogeneous in terms of OM type, containing a mixture of buried OM of all sizes and ages, and in terms of physical structure, with inorganic particles of widely varied texture and the potential to set up steep diversity and productivity gradients under saturated conditions (Ellis et al., 1998; Findlay et al., 2003). The epilithic habitat provides no OM at early stages in biofilm development, though mature biofilms contain primary producers that exude C compounds, and entrain particulate OM. Water column habitat supports both suspended and particle-associated bacterioplankton (Crump et al., 1999) and contains a combination of algal and exogenous C. In addition to the contrasting OM substrates characterizing these habitats, they present surfaces with different texture and area for microbial colonization: surface roughness and water flow conditions affect the trajectory and diversity of cells inhabiting biofilms and the exchange of cells and particles between biofilms and the surface water (Battin et al., 2003; Arnon et al., 2010; Singer et al., 2010). This mosaic of selective habitats within a stream (Pringle et al., 1988), combined with the strong mass effects of flowing waters (Crump et al., 2007, 2012), make lotic ecosystems prime test grounds for questions about microbial community assembly within a metacommunity context (Logue et al., 2011).

Defined Drivers Effects

Specific drivers of environmental change had varied frequencies of significant influence on stream and river microbial diversity (Figure 5), with the exception of the always-significant effect of metals. As noted earlier, the only study that reported no significant differentiation among OM compartments was undertaken in metal-contaminated streams (Figure 3; Sridhar et al., 2008). This ubiquitous result reflects the acute toxic effects that metals can have on cells with no tolerance adaptations (Genter and Lehman, 2000). Also, large changes in pH and concentrations of electron donors and acceptors, as found in acid mine drainage streams, creates conditions favorable for very specific microbial metabolic functions and taxonomic groups (Niyogi et al., 2002; Kim et al., 2009; Yu et al., 2010). In soils, pH can vary widely and is correlated with broad differences in microbial community composition and function (Sinsabaugh et al., 2008; Lauber et al., 2009; Rousk et al., 2010); however, in lotic ecosystems the isolated effect of pH on microbial diversity has been studied less frequently and has varied effects on microbial diversity (Fierer et al., 2007; Simon et al., 2009). Field studies within the “metals” category were associated with current or historic mining or industrial activities in the watershed (Feris et al., 2003a; Ancion et al., 2010); however, none were associated with an effect of pH in isolation from metals contamination (Baudoin et al., 2008). This reflects the common covariance of multiple environmental stressors, such as metals and pH, associated with watershed mining activities (Palmer et al., 2010) and urbanization (Grimm et al., 2008), and highlights the dramatic impact that these factors may have in delimiting microbial niches.

In contrast, significant land-use and nutrients effects on lotic microbial diversity were least often observed (Figures 5 and 6). This may point to a relatively high level of functional diversity and redundancy regarding nutrient kinetics within natural microbial communities: cells may have strategies to operate under a range of nutrient concentrations (Findlay and Sinsabaugh, 2003), and taxa with contrasting nutrient affinities may often coexist (Martens-Habbena et al., 2009), possibly due to dormancy or low but persistent viability during suboptimal conditions (Jones and Lennon, 2010; Shade et al., 2014). In complement, other environmental drivers may have a stronger effect on limiting the competitive advantage of some microbial taxa than nutrient availability. Metals concentrations (Ancion et al., 2013), temperature (Sliva and Williams, 2005; Zhang et al., 2012), OM quantity or quality (Zoppini et al., 2010; Marano et al., 2011), hydrological factors (Sliva and Williams, 2005; Zoppini et al., 2010), or other site-specific factors (Oliveira and Goulder, 2006; Comte and del Giorgio, 2009; Perez et al., 2012; Washington et al., 2013) could cause stricter physiological limitations on cell success than nutrient availability. This functional redundancy and relative insensitivity of stream and river microbiota to changing nutrient concentrations helps to explain situations in which nutrient concentrations are better predictors of microbial function than microbial diversity (Baxter et al., 2012).

On the other hand, it is important to remember that, while least common, nutrient effects on lotic microbial diversity were significant in 79% of studies. These effects included a number of experiments that applied nutrient enrichment in the absence of other environmental variation (Sridhar and Bärlocher, 2000; Olapade and Leff, 2005; Artigas et al., 2008; Van Horn et al., 2011). Many environmental nutrient gradients include covariates, however. Wastewater treatment effluent, which can cause shifts in river temperature, salinity and bacterial load, as well as increased nutrient concentration, was often influential on microbial diversity (Wakelin et al., 2008; Angel et al., 2010; Drury et al., 2013; Sonthiphand et al., 2013). Nutrient impacts on stream microbiota from land-use change are often accompanied by differences in riparian vegetation and cover (thus OM quality), temperature, geomorphology and hydrological connectivity, and organic pollutants (Findlay and Sinsabaugh, 2006; Dorigo et al., 2009; Villeneuve et al., 2011). Thus, it is critical to consider both the individual and interactive impacts of changes in nutrient concentrations and other environmental alterations on microbial diversity, functional redundancy, and integrated function. Future studies on lotic microbial nutrient sensitivity should strive to utilize experimental data, in addition to observational data, to make the largest strides in understanding the functional redundancy and hierarchical environmental controls on stream microbial structure and function (Goodman et al., 2015).

Lotic Microbial Diversity is Critical and Understudied

While the importance of microbial diversity to ecosystem function, and the threats that environmental changes pose to diversity and function, are key areas of research in all aquatic ecosystems, lotic microbial diversity has generally received less attention than marine and lentic microbial diversity (Zinger et al., 2012). Comparing and contrasting key points in the current state of knowledge in both lotic and better-studied aquatic systems highlights areas where complementary research can further advance understanding of diversity-function relationships in aquatic systems generally.

While most work on aquatic microbial diversity has focused on planktonic communities (Zwart et al., 2002; Hahn, 2006; Smith, 2007; Newton et al., 2011; Ladau et al., 2013), in lotic ecosystems the diversity of surface-attached biofilms in benthic habitats is better studied (Figure 1D). The dominant controls on bacterioplankton diversity, such as light and algal abundance, predation, temperature and salinity (Fuhrman et al., 2006; Kent et al., 2007; Lefort and Gasol, 2013), may differ from dominant controls on benthic microbial diversity, due to the contrasting energy sources and physical conditions of pelagic versus benthic habitats (Covich et al., 2004). A predominant contrast between these habitats is the relative importance of algal vs. terrestrial-derived OM substrates, and the coarse differences between water column, epilithon, CPOM, FBOM, and sediment associated bacterial community composition in lotic systems (Figure 4; Table 2) may be related in part to autochthonous versus allochtonous OM source, as noted earlier. While it is possible that the structure and function of microbiota on allochthonous substrates responds differently to environmental changes than those associated with autochthonous substrates (Dodds, 2006), like primary production, decomposition and microbial mineralization of terrestrial OM in streams responds positively to changes in nutrient concentrations and temperature (Boyero et al., 2011; Rosemond et al., 2015). The topic of microbial metabolism of algal versus terrestrial OM is increasingly relevant in all aquatic systems (Del Giorgio et al., 1997; Pace et al., 2004), and hypotheses based on microbial diversity and function in heterogeneous lotic habitats can inform understanding of carbon cycling across changing, and connected, aquatic landscapes (Battin et al., 2008).

In addition to the organic substrate heterogeneity presented by the benthos-dominated lotic ecosystem, the level of interaction between benthic and pelagic habitats affects aquatic diversity and function (Covich et al., 2004). Bacterioplankton community composition can be temporally predictable, in concert with temporal variation in environmental parameters such as light and temperature (Fuhrman et al., 2006; Kan et al., 2006; Kent et al., 2007; Crump et al., 2009; Eiler et al., 2012). Benthic surface- and sediment-attached microbiota are exposed to variability in physical factors, such as shear stress and surface roughness, as well as changes in light and water quality, and biofilm formation is a predominant characteristic of lotic microbiota. Thus, the large heterogeneity in surfaces available for colonization within a stream reach presents a variety of contrasting selective environments (Battin et al., 2007). Also, bacterioplankon diversity is impacted by water residence time, (Crump et al., 2004; Lindström and Bergström, 2004), and the flowing water of lotic systems clearly acts to transport microbial cells relatively quickly from up- to downstream habitats (Crump et al., 2007; Riemann et al., 2008). Thus, both dispersal and environmental filtering are strong forces in microbial biofilm community assembly in stream and river ecosystems, making lotic systems highly appropriate for understanding metacommunity dynamics (Logue et al., 2011; Besemer et al., 2012, 2013).

Surface-attached and bed sediment-entrained cells are not always accounted for in broad views of microbial life in aquatic ecosystems (Whitman et al., 1998), yet their activity drives biogeochemical processes at reach, watershed and continental scales (Likens et al., 1970; Mulholland et al., 2008; Rosemond et al., 2015). Further research on lotic microbial diversity, including themes such as community assembly, OM source and metabolism, and functional diversity and redundancy under multi-factor environmental variability, is critical to understanding and managing aquatic ecosystem functions in a changing world. Yet lotic microbial diversity is still understudied: Many studies to date are observational, few are experimental; most take place within one stream, few employ cross-site comparisons that would facilitate identification of universal drivers. Given the importance of stream microbes to global biogeochemical cycles, the rapidly increasing accessibility of molecular tools and data, and the relevance of stream microbiota to larger ecological questions, there is still a lot to be learned about lotic microbial diversity.

Author Contribution

LZ collected and synthesized the data and wrote the manuscript.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

Many thanks to the many people with whom I have discussed stream microbial ecology over the years, especially Cliff Dahm, Tina Vesbach, and Bob Sinsabaugh, to the editors of this special issue for the forum, to Walter Dodds and Allison Veach for their thoughtful feedback on the manuscript, and to the reviewers of this manuscript for their constructive comments.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: http://journal.frontiersin.org/article/10.3389/fmicb.2015.00454/abstract

References

- Allison S. D., Martiny J. B. H. (2008). Resistance, resilience, and redundancy in microbial communities. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 105 11512–11519 10.1073/pnas.0801925105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ancion P. Y., Lear G., Dopheide A., Lewis G. D. (2013). Metal concentrations in stream biofilm and sediments and their potential to explain biofilm microbial community structure. Environ. Pollut. 173 117–124 10.1016/j.envpol.2012.10.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ancion P. Y., Lear G., Lewis G. D. (2010). Three common metal contaminants of urban runoff (Zn, Cu and Pb) accumulate in freshwater biofilm and modify embedded bacterial communities. Environ. Pollut. 158 2738–2745 10.1016/j.envpol.2010.04.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Angel R., Asaf L., Ronen Z., Nejidat A. (2010). Nitrogen transformations and diversity of ammonia-oxidizing bacteria in a desert ephemeral stream receiving untreated wastewater. Microb. Ecol. 59 46–58 10.1007/s00248-009-9555-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnon S., Marx L. P., Searcy K. E., Packman A. I. (2010). Effects of overlying velocity, particle size, and biofilm growth on stream-subsurface exchange of particles. Hydrol. Process. 24 108–114 10.1002/hyp.7490 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Artigas J., Romani A. M., Sabater S. (2008). Effect of nutrients on the sporulation and diversity of aquatic hyphomycetes on submerged substrata in a Mediterranean stream. Aquatic Bot. 88 32–38 10.1016/j.aquabot.2007.08.005 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bärlocher F. (1982). Conidium production from leaves and needles in four streams. Can. J. Bot. 60 1487–1494 10.1139/b82-190 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Battin T. J., Kaplan L. A., Findlay S., Hopkinson C. S., Marti E., Packman A. I., et al. (2008). Biophysical controls on organic carbon fluxes in fluvial networks. Nat. Geosci. 1 95–100 10.1038/ngeo101 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Battin T. J., Kaplan L. A., Newbold J. D., Cheng X. H., Hansen C. (2003). Effects of current velocity on the nascent architecture of stream microbial biofilms. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 69 5443–5452 10.1128/AEM.69.9.5443-5452.2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Battin T. J., Sloan W. T., Kjelleberg S., Daims H., Head I. M., Curtis T. P., et al. (2007). Microbial landscapes: new paths to biofilm research. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 5 76–81 10.1038/nrmicro1556 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Battin T. J., Wille A., Sattler B., Psenner R. (2001). Phylogenetic and functional heterogeneity of sediment biofilms along environmental gradients in a glacial stream. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 67 799–807 10.1128/AEM.67.2.799-807.2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baudoin J. M., Guerold F., Felten V., Chauvet E., Wagner P., Rousselle P. (2008). Elevated aluminium concentration in acidified headwater streams lowers aquatic hyphomycete diversity and impairs leaf-litter breakdown. Microb. Ecol. 56 260–269 10.1007/s00248-007-9344-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baxter A. M., Johnson L., Edgerton J., Royer T., Leff L. G. (2012). Structure and function of denitrifying bacterial assemblages in low-order Indiana streams. Freshw. Sci. 31 304–317 10.1899/11-066.1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bell C. R., Holderfranklin M. A., Franklin M. (1982a). Correlations between predominant heterotrophic bacteria and physiochemical water-quality parameters in 2 Canadian rivers. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 43 269–283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bell C. R., Holderfranklin M. A., Franklin M. (1982b). Seasonal fluctuations in river bacteria as measured by multivariate statistical-analysis of continuous cultures. Can. J. Microbiol. 28 959–975 10.1139/m82-144 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Besemer K., Hodl I., Singer G., Battin T. J. (2009). Architectural differentiation reflects bacterial community structure in stream biofilms. ISME J. 3 1318–1324 10.1038/ismej.2009.73 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Besemer K., Peter H., Logue J. B., Langenheder S., Lindström E. S., Tranvik L. J., et al. (2012). Unraveling assembly of stream biofilm communities. ISME J. 6 1459–1468 10.1038/ismej.2011.205 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Besemer K., Singer G., Quince C., Bertuzzo E., Sloan W., Battin T. J. (2013). Headwaters are critical reservoirs of microbial diversity for fluvial networks. Proc. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 280:20131760 10.1098/rspb.2013.1760 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyero L., Pearson R. G., Gessner M. O., Barmuta L. A., Ferreira V., Graca M. A. S., et al. (2011). A global experiment suggests climate warming will not accelerate litter decomposition in streams but might reduce carbon sequestration. Ecol. Lett. 14 289–294 10.1111/j.1461-0248.2010.01578.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charcosset J. Y., Gardes M. (1999). Infraspecific genetic diversity and substrate preference in the aquatic hyphomycete Tetrachaetum elegans. Mycol. Res. 103 736–742 10.1017/S0953756298007606 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chiaramonte J. B., Roberto M. D., Pagioro T. A. (2013). Seasonal dynamics and community structure of bacterioplankton in Upper Parana River floodplain. Microb. Ecol. 66 773–783 10.1007/s00248-013-0292-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Comte J., del Giorgio P. A. (2009). Links between resources, C metabolism and the major components of bacterioplankton community structure across a range of freshwater ecosystems. Environ. Microbiol. 11 1704–1716 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2009.01897.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Comte J. R. M., Fauteux L., Del Giorgio P. A. (2013). Links between metabolic plasticity and functional redundancy in freshwater bacterioplankton communities. Front. Microbiol. 4:112 10.3389/fmicb.2013.00112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cotner J. B., Biddanda B. A. (2002). Small players, large role: microbial influence on biogeochemical processes in pelagic aquatic ecosystems. Ecosystems 5 105–121 10.1007/s10021-001-0059-3 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Covich A. P., Austen M. C., Barlocher F., Chauvet E., Cardinale B. J., Biles C. L. (2004). The role of biodiversity in the functioning of freshwater and marine benthic ecosystems. Bioscience 54 767–775 10.1641/0006-3568(2004)054[0767:TROBIT]2.0.CO;2 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Crump B. C., Adams H. E., Hobbie J. E., Kling G. W. (2007). Biogeography of bacterioplankton in lakes and streams of an arctic tundra catchment. Ecology 88 1365–1378 10.1890/06-0387 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crump B. C., Amaral-Zettler L. A., Kling G. W. (2012). Microbial diversity in arctic freshwaters is structured by inoculation of microbes from soils. ISME J. 6 1629–1639 10.1038/ismej.2012.9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crump B. C., Armbrust E. V., Baross J. A. (1999). Phylogenetic analysis of particle-attached and free-living bacterial communities in the Columbia river, its estuary, and the adjacent coastal ocean. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 65 3192–3204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crump B. C., Baross J. A. (2000). Archaeaplankton in the Columbia river, its estuary and the adjacent coastal ocean, USA. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 31 231–239 10.1111/j.1574-6941.2000.tb00688.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crump B. C., Hobbie J. E. (2005). Synchrony and seasonality in bacterioplankton communities of two temperate rivers. Limnol. Oceanogr. 50 1718–1729 10.4319/lo.2005.50.6.1718 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Crump B. C., Hopkinson C. S., Sogin M. L., Hobbie J. E. (2004). Microbial biogeography along an estuarine salinity gradient: combined influences of bacterial growth and residence time. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 70 1494–1505 10.1128/AEM.70.3.1494-1505.2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crump B. C., Peterson B. J., Raymond P. A., Amon R. M. W., Rinehart A., Mcclelland J. W., et al. (2009). Circumpolar synchrony in big river bacterioplankton. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 106 21208–21212 10.1073/pnas.0906149106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Del Giorgio P. A., Cole J. J., Cimbleris A. (1997). Respiration rates in bacteria exceed phytoplankton production in unproductive aquatic systems. Nature 385 148–151 10.1038/385148a0 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dodds W. K. (2006). Eutrophication and trophic state in rivers and streams. Limnol. Oceanogr. 51 671–680 10.4319/lo.2006.51.1_part_2.0671 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dodds W. K., Lopez A. J., Bowden W. B., Gregory S., Grimm N. B., Hamilton S. K., et al. (2000). N uptake as a function of concentration in streams. J. North Am. Benthol. Soc. 21 206–220 10.2307/1468410 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dorigo U., Lefranc M., Leboulanger C., Montuelle B., Humbert J. F. (2009). Spatial heterogeneity of periphytic microbial communities in a small pesticide-polluted river. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 67 491–501 10.1111/j.1574-6941.2008.00642.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drury B., Rosi-Marshall E., Kelly J. J. (2013). Wastewater treatment effluent reduces the abundance and diversity of benthic bacterial communities in urban and suburban rivers. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 79 1897–1905 10.1128/AEM.03527-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dudgeon D., Arthington A. H., Gessner M. O., Kawabata Z.-I., Knowler D. J., Lévêque C., et al. (2006). Freshwater biodiversity: importance, threats, status and conservation challenges. Biol. Rev. 81 163–182 10.1017/S1464793105006950 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eiler A., Heinrich F., Bertilsson S. (2012). Coherent dynamics and association networks among lake bacterioplankton taxa. ISME J. 6 330–342 10.1038/ismej.2011.113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellis B. K., Stanford J. A., Ward J. V. (1998). Microbial assemblages and production in alluvial aquifers of the Flathead River, Montana, USA. J. North Am. Benthol. Soc. 17 382–402 10.2307/1468361 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fazi S., Vazquez E., Casamayor E. O., Amalfitano S., Butturini A. (2013). Stream hydrological fragmentation drives bacterioplankton community composition. PLoS ONE 8:e64109 10.1371/journal.pone.0064109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feris K., Ramsey P., Frazar C., Moore J. N., Gannon J. E., Holbert W. E. (2003a). Differences in hyporheic-zone microbial community structure along a heavy-metal contamination gradient. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 69 5563–5573 10.1128/AEM.69.9.5563-5573.2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feris K. P., Ramsey P. W., Frazar C., Rillig M. C., Gannon J. E., Holben W. E. (2003b). Structure and seasonal dynamics of hyporheic zone microbial communities in free-stone rivers of the western United States. Microb. Ecol. 46 200–215 10.1007/s00248-002-0100-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fierer N., Morse J. L., Berthrong S. T., Bernhardt E. S., Jackson R. B. (2007). Environmental controls on the landscape-scale biogeography of stream bacterial communities. Ecology 88 2162–2173 10.1890/06-1746.1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Findlay S. (2010). Stream microbial ecology. J. North Am. Benthol. Soc. 29 170–181 10.1899/09-023.1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Findlay S., Sinsabaugh R. L. (2003). Response of hyporheic biofilm metabolism and community structure to nitrogen amendments. Aquat. Microbial. Ecol. 33 127–136 10.3354/ame033127 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Findlay S., Sinsabaugh R. L. (2006). Large-scale variation in subsurface stream biofilms: a cross-regional comparison of metabolic function and community similarity. Microb. Ecol. 52 491–500 10.1007/s00248-006-9095-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Findlay S. E. G., Sinsabaugh R. L., Sobczak W. V., Hoostal M. (2003). Metabolic and structural response of hyporheic microbial communities to variations in supply of dissolved organic matter. Limnol. Oceanogr. 48 1608–1617 10.4319/lo.2003.48.4.1608 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Finlay B. J. (2002). Global dispersal of free-living microbial eukaryote species. Science 296 1061–1063 10.1126/science.1070710 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher S. G., Grimm N. B., Martí E., Holmes R. M., Jones J. B. (1998). Material spiraling in stream corridors: a telescoping ecosystem model. Ecosystems 1 19–34 10.1007/s100219900003 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fox J. (2005). The R Commander: a basic-statistics graphic user interface to R. J. Statist. Software 19 1–42. [Google Scholar]

- Fuhrman J. A., Hewson I., Schwalbach M. S., Steele J. A., Brown M. V., Naeem S. (2006). Annually reoccurring bacterial communities are predictable from ocean conditions. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 103 13104–13109 10.1073/pnas.0602399103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geesey G. G., Richardson W. T., Yeomans H. G., Irvin R. T., Costerton J. W. (1977). Microscopic examination of natural sessile bacterial populations from an alpine stream. Can. J. Microbiol. 23 1733–1736 10.1139/m77-249 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Genter R. B., Lehman R. M. (2000). Metal toxicity inferred from algal population density, heterotrophic substrate use, and fatty acid profile in a small stream. Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 19 869–878 10.1002/etc.5620190413 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gessner M. O., Chauvet E. (1994). Importance of stream microfugi in controlling breakdown rates of leaf litter. Ecology 75 1807–1817 10.2307/1939639 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gessner M. O., Swan C. M., Dang C. K., Mckie B. G., Bardgett R. D., Wall D. H., et al. (2010). Diversity meets decomposition. Trends Ecol. Evol. 25 372–380 10.1016/j.tree.2010.01.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gessner M. O., Thomas M., Jeanlouis A. M., Chauvet E. (1993). Stable successional patterns of aquatic hyphomycetes on leaves decaying in a summer cool stream. Mycol. Res. 97 163–172 10.1016/S0953-7562(09)80238-4 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Goodman K. J., Parker S. M., Edmonds J. W., Zeglin L. H. (2015). Expanding the scale of aquatic sciences: the role of the National Ecological Observatory Network (NEON). Freshw. Sci. 34 377–385 10.1086/679459 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Grimm N. B., Foster D., Groffman P., Grove J. M., Hopkinson C. S., Nadelhoffer K. J., et al. (2008). The changing landscape: ecosystem responses to urbanization and pollution across climatic and societal gradients. Front. Ecol. Environ. 6 264 10.1890/070147 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hahn M. W. (2006). The microbial diversity of inland waters. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 17 256–261 10.1016/j.copbio.2006.05.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall R. O., Meyer J. L. (1998). The trophic significance of bacteria in a detritus-based stream food web. Ecology 79 1995–2012 10.1890/0012-9658(1998)079[1995:TTSOBI]2.0.CO;2 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hedges L. V. (1992). Modeling publication selection effects in meta-analysis. Statist. Sci. 7 246–255 10.1214/ss/1177011364 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hieber M., Gessner M. O. (2002). Contribution of stream detrivores, fungi, and bacteria to leaf breakdown based on biomass estimates. Ecology 83 1026–1038 10.1890/0012-9658(2002)083[1026:COSDFA]2.0.CO;2 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Horner-Devine M. C., Leibold M. A., Smith V. H., Bohannan B. J. M. (2003). Bacterial diversity patterns along a gradient of primary productivity. Ecol. Lett. 6 613–622 10.1046/j.1461-0248.2003.00472.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Horner-Devine M. C., Silver J. M., Leibold M. A., Bohannan B. J. M., Colwell R. K., Fuhrman J. A., et al. (2007). A comparison of taxon co-occurrence patterns for macro- and microorganisms. Ecology 88 1345–1353 10.1890/06-0286 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hullar M. A. J., Kaplan L. A., Stahl D. A. (2006). Recurring seasonal dynamics of microbial communities in stream habitats. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 72 713–722 10.1128/AEM.72.1.713-722.2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hynes H. B. N. (1975). The stream and its valley. Verh. Int. Ver. Theor. Angew. Limnol. 19 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Jones S. E., Lennon J. T. (2010). Dormancy contributes to the maintenance of microbial diversity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 107 5881–5886 10.1073/pnas.0912765107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kan J., Crump B. C., Wang K., Chen F. (2006). Bacterioplankton community in Chesapeake Bay: predictable or random assemblages. Limnol. Oceanogr. 51 2157–2169 10.4319/lo.2006.51.5.2157 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kemp M. J., Dodds W. K. (2001). Centimeter-scale patterns in dissolved oxygen and nitrificaton rates in a prairie stream. J. North Am. Benthol. Soc. 20 347–357 10.2307/1468033 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kent A. D., Yannarell A. C., Rusak J. A., Triplett E. W., McMahon K. D. (2007). Synchrony in aquatic microbial community dynamics. ISME J. 1 38–47 10.1038/ismej.2007.6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim J., Koo S. Y., Kim J. Y., Lee E. H., Lee S. D., Ko K. S., et al. (2009). Influence of acid mine drainage on microbial communities in stream and groundwater samples at Guryong Mine, South Korea. Environ. Geol. 58 1567–1574 10.1007/s00254-008-1663-8 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ladau J., Sharpton T. J., Finucane M. M., Jospin G., Kembel S. W., O’dwyer J., et al. (2013). Global marine bacterial diversity peaks at high latitudes in winter. ISME J. 7 1669–1677 10.1038/ismej.2013.37 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langenheder S., Berga M., Ostman O., Szekely A. J. (2012). Temporal variation of beta-diversity and assembly mechanisms in a bacterial metacommunity. ISME J. 6 1107–1114 10.1038/ismej.2011.177 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lauber C. L., Hamady M., Knight R., Fierer N. (2009). Pyrosequencing-based assessment of soil pH as a predictor of soil bacterial community structure at the continental scale. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 75 5111–5120 10.1128/AEM.00335-09 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lefort T., Gasol J. M. (2013). Global-scale distributions of marine surface bacterioplankton groups along gradients of salinity, temperature, and chlorophyll: a meta-analysis of fluorescence in situ hybridization studies. Aquat. Microb. Ecol. 70 111–130 10.3354/ame01643 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Likens G. E., Bormann F. H., Johnson N. M., Fisher D. W., Pierce R. S. (1970). Effects of forest cutting and herbicide treatment on nutrient budgets in the Hubbard Brook watershed-ecosystem. Ecol. Monogr. 40 23–47 10.2307/1942440 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lindeman R. L. (1942). The trophic-dynamic aspect of ecology. Ecology 23 399–418 10.2307/1930126 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lindström E. S., Bergström A.-K. (2004). Influence of inlet bacteria on bacterioplankton assemblage composition in lakes of different hydraulic retention time. Limnol. Oceanogr. 49 125–136 10.4319/lo.2004.49.1.0125 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Logue J. B., Mouquet N., Peter H., Hillebrand H., Metacommunity Working Group. (2011). Empirical approaches to metacommunities: a review and comparison with theory. Trends Ecol. Evol. 26 482–491 10.1016/j.tree.2011.04.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyautey E., Jackson C. R., Cayrou J., Rols J. L., Garabetian F. (2005). Bacterial community succession in natural river biofilm assemblages. Microb. Ecol. 50 589–601 10.1007/s00248-005-5032-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malmqvist B., Rundle S. (2002). Threats to the running water ecosystems of the world. Environ. Conservation 2 134–153 10.1017/S0376892902000097 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Marano A. V., Barrera M. D., Steciow M. M., Gleason F. H., Pires-Zottarelli C. L. A., Donadelli J. L. (2011). Diversity of zoosporic true fungi and heterotrophic straminipiles in Las Canas stream (Buenos Aires, Argentina): assemblages colonizing baits. Fundam. Appl. Limnol. 178 203–218 10.1127/1863-9135/2011/0178-0203 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Martens-Habbena W., Berube P. M., Urakawa H., De La Torre J. R., Stahl D. A. (2009). Ammonia oxidation kinetics determine niche separation of nitrifying Archaea and Bacteria. Nature 461 976–979 10.1038/nature08465 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McArthur J. V., Leff L. G., Smith M. H. (1992). Genetic diversity of bacteria along a stream continuum. J. North Am. Benthol. Soc. 11 269–277 10.2307/1467647 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McClain M. E., Boyer E. W., Dent C. L., Gergel S. E., Grimm N. B., Groffman P. M., et al. (2003). Biogeochemical hot spots and hot moments at the interface of terrestrial and aquatic ecosystems. Ecosystems 6 301–312 10.1007/s10021-003-0161-9 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer J. L. (1994). The microbial loop in flowing waters. Microb. Ecol. 28 195–199 10.1007/BF00166808 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milner C. R., Goulder R. (1984). Bacterioplankton in an urban river - the effects of a metal-bearing tributary. Water Res. 18 1395–1399 10.1016/0043-1354(84)90009-5 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Minshall G. W., Cummins K. W., Petersen R. C., Cushing C. E., Bruns D. A., Sedell J. R., et al. (1985). Developments in stream ecosystem theory. Can. J. Fisheries Aquat. Sci. 42 1045–1055 10.1139/f85-130 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mulholland P. J., Helton A. M., Poole G. C., Hall R. O., Hamilton S. K., Peterson B. J., et al. (2008). Stream denitrification across biomes and its response to anthropogenic nitrate loading. Nature 452 202–205 10.1038/nature06686 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newton R. J., Jones S. E., Eiler A., Mcmahon K. D., Bertilsson S. (2011). A guide to the natural history of freshwater lake bacteria. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 75 14–49 10.1128/MMBR.00028-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nikolcheva L. G., Bärlocher F. (2005). Seasonal and substrate preferences of fungi colonizing leaves in streams: traditional versus molecular evidence. Environ. Microbiol. 7 270–280 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2004.00709.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nikolcheva L. G., Cockshutt A. M., Barlocher F. (2003). Determining diversity of freshwater fungi on decaying leaves: comparison of traditional and molecular approaches. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 69 2548–2554 10.1128/AEM.69.5.2548-2554.2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niyogi D. K., Mcknight D. M., Lewis W. M. (2002). Fungal communities and biomass in mountain streams affected by mine drainage. Archiv. Fur. Hydrobiol. 155 255–271. [Google Scholar]

- Nold S., Zwart G. (1998). Patterns and governing forces in aquatic microbial communities. Aquat. Ecol. 32 17–35 10.1023/A:1009991918036 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Olapade O. A., Leff L. G. (2004). Seasonal dynamics of bacterial assemblages in epilithic biofilms in a northeastern Ohio stream. J. North Am. Benthol. Soc. 23 686–700 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Olapade O. A., Leff L. G. (2005). Seasonal response of stream biofilm communities to dissolved organic matter and nutrient enrichments. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 71 2278–2287 10.1128/AEM.71.5.2278-2287.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oliveira M. A., Goulder R. (2006). The effects of sewage-treatment-works effluent on epilithic bacterial and algal communities of three streams in Northern England. Hydrobiologia 568 29–42 10.1007/s10750-006-0013-7 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pace M. L., Cole J. J., Carpenter S. R., Kitchell J. F., Hodgson J. R., Van De Bogert M. C., et al. (2004). Whole-lake carbon-13 additions reveal terrestrial support of aquatic food webs. Nature 427 240–243 10.1038/nature02227 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pace N. R. (1997). A molecular view of microbial diversity and the biosphere. Science 276 734–740 10.1126/science.276.5313.734 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palmer M. A., Bernhardt E. S., Schlesinger W. H., Eshleman K. N., Foufoula-Georgiou E., Hendryx M. S., et al. (2010). Mountaintop mining consequences. Science 327 148–149 10.1126/science.1180543 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palmer M. A., Febria C. M. (2012). The heartbeat of ecosystems. Science 336 1393–1394 10.1126/science.1223250 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perez J., Descals E., Pozo J. (2012). Aquatic hyphomycete communities associated with decomposing alder leaf litter in reference headwater streams of the Basque Country (northern Spain). Microb. Ecol. 64 279–290 10.1007/s00248-012-0022-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peterson B. J., Wollheim W. M., Mulholland P. J., Webster J. R., Meyer J. L., Tank J. L., et al. (2001). Control of nitrogen export from watersheds by headwater streams. Science 292 86–90 10.1126/science.1056874 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillippot L., Andersson S. G. E., Battin T. J., Prosser J. I., Schimel J. P., Whitman W. B., et al. (2010). The ecological conherence of high bacterial taxonomic ranks. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 8 523–529 10.1038/nrmicro2367 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poff N. L., Ward J. V. (1989). Implications of streamflow variability and predictability for lotic community structure: a regional analysis of streamflow patterns. Can. J. Fisheries Aquat. Sci. 46 1805–1817 10.1139/f89-228 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Portillo M. C., Anderson S. P., Fierer N. (2012). Temporal variability in the diversity and composition of stream bacterioplankton communities. Environ. Microbiol. 14 2417–2428 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2012.02785.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pringle C. M., Naiman R. J., Bretschko G., Karr J. R., Oswood M. W., Webster J. R., et al. (1988). Patch dynamics in lotic systems: the stream as a mosiac. J. North Am. Benthol. Soc. 7 503–524 10.2307/1467303 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- R Core Development Team. (2010). R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. Vienna: R Foundation for Statistical Computing. [Google Scholar]

- Rees G. N., Watson G. O., Baldwin D. S., Mitchell A. M. (2006). Variability in sediment microbial communities in a semipermanent stream: impact of drought. J. North Am. Benthol. Soc. 25 370–378 10.1899/0887-3593(2006)25[370:VISMCI]2.0.CO;2 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Riemann L., Leitet C., Pommier T., Simu K., Holmfeldt K., Larsson U., et al. (2008). The native bacterioplankton community in the Central Baltic Sea is influenced by freshwater bacterial species. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 74 503–515 10.1128/AEM.01983-07 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosemond A. D., Benstead J. P., Bumpers P. M., Gulis V., Kominoski J. S., Manning D. W. P., et al. (2015). Experimental nutrient additions accelerate terrestrial carbon loss from stream ecosystems. Science 347 1142–1145 10.1126/science.aaa1958 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenthal R. (1979). The “file drawer problem” and tolerance for null results. Psychol. Bull. 86 638–641 10.1037/0033-2909.86.3.638 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rousk J., Baath E., Brookes P. C., Lauber C. L., Lozupone C., Caporaso J. G., et al. (2010). Soil bacterial and fungal communities across a pH gradient in an arable soil. ISME J. 4 1340–1351 10.1038/ismej.2010.58 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shade A., Caporaso J. G., Handelsman J., Knight R., Fierer N. (2013). A meta-analysis of changes in bacterial and archaeal communities with time. ISME J. 7 1493–1506 10.1038/ismej.2013.54 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shade A., Jones S. E., Caporaso J. G., Handelsman J., Knight R., Fierer N., et al. (2014). Conditionally rare taxa disproportionately contribute to temporal changes in microbial diversity. mBio 5:e01371-14. 10.1128/mBio.01371-14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shade A., Peter H., Allison S. D., Baho D. L., Berga M., Burgmann H., et al. (2012). Fundamentals of microbial community resistance and resilience. Front. Microbiol. 3:417 10.3389/fmicb.2012.00417 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simon K. S., Simon M. A., Benfield E. F. (2009). Variation in ecosystem function in Appalachian streams along an acidity gradient. Ecol. Appl. 19 1147–1160 10.1890/08-0571.1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singer G., Besemer K., Schmitt-Kopplin P., Hodl I., Battin T. J. (2010). Physical heterogeneity increases biofilm resource use and its molecular diversity in stream mesocosms. PLoS ONE 5:e9988 10.1371/journal.pone.0009988 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sinsabaugh R. L., Lauber C. L., Weintraub M. N., Ahmed B., Allison S. D., Crenshaw C., et al. (2008). Stoichiometry of soil enzyme activity at global scale. Ecol. Lett. 11 1252–1264 10.1111/j.1461-0248.2008.01245.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sinsabaugh R. L., Weiland T., Linkins A. E. (1992). Enzymatic and molecular analysis of microbial communities associated with lotic particulate organic matter. Freshw. Biol. 28 393–404 10.1111/j.1365-2427.1992.tb00597.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sliva L., Williams D. D. (2005). Exploration of riffle-scale interactions between abiotic variables and microbial assemblages in the hyporheic zone. Can. J. Fisheries Aquat. Sci. 62 276–290 10.1139/f04-190 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Smith V. H. (2007). Microbial diversity-productivity relationships in aquatic ecosystems. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 62 181–186 10.1111/j.1574-6941.2007.00381.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sonthiphand P., Cejudo E., Schiff S. L., Neufeld J. D. (2013). Wastewater effluent impacts ammonia-oxidizing prokaryotes of the Grand River, Canada. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 79 7454–7465 10.1128/AEM.02202-13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sridhar K. R., Bärlocher F. (2000). Initial colonization, nutrient supply, and fungal activity on leaves decaying in streams. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 66 1114–1119 10.1128/AEM.66.3.1114-1119.2000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sridhar K. R., Barlocher F., Wennrich R., Krauss G. J., Krauss G. (2008). Fungal biomass and diversity in sediments and on leaf litter in heavy metal contaminated waters of Central Germany. Fundam. Appl. Limnol. 171 63–74 10.1127/1863-9135/2008/0171-0063 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Suberkropp K., Godshalk G. L., Klug M. J. (1976). Changes in the chemical composition of leaves during processing in a woodland stream. Ecology 57 720–727 10.2307/1936185 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Suberkropp K., Klug M. J. (1976). Fungi and bacteria associated with leaves during processing in a woodland stream. Ecology 57 717–719 10.2307/1936184 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sutton S. D., Findlay R. H. (2003). Sedimentary microbial community dynamics in a regulated stream: East Fork of the Little Miami River, Ohio. Environ. Microbiol. 5 256–266 10.1046/j.1462-2920.2003.00396.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tank J. L., Rosi-Marshall E. J., Griffiths N. A., Entrekin S. A., Stephen M. L. (2010). A review of allochthonous organic matter dynamics and metabolism in streams. J. North Am. Benthol. Soc. 29 118–146 10.1899/08-170.1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Valett H. M., Dahm C. N., Campana M. E., Morrice J. A., Baker M. A., Fellows C. S. (1997). Hydrologic influences on groundwater surface water ecotones: heterogeneity in nutrient composition and retention. J. North Am. Benthol. Soc. 16 239–247 10.2307/1468254 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Valett H. M., Thomas S. A., Mulholland P. J., Webster J. R., Dahm C. N., Fellows C. S., et al. (2008). Endogenous and exogenous control of ecosystem function: n cycling in headwater streams. Ecology 89 3515–3527 10.1890/07-1003.1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Horn D. J., Sinsabaugh R. L., Takacs-Vesbach C. D., Mitchell K. R., Dahm C. N. (2011). Response of heterotrophic stream biofilm communities to a gradient of resources. Aquat. Microbial. Ecol. 64 149–161 10.3354/ame01515 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Vannote R. L., Minshall G. W., Cummins K. W., Sedell J. R., Cushing C. E. (1980). The river continuum concept. Can. J. Fisheries Aquat. Sci. 37 130–137 10.1139/f80-017 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Villeneuve A., Bouchez A., Montuelle B. (2011). In situ interactions between the effects of season, current velocity and pollution on a river biofilm. Freshw. Biol. 56 2245–2259 10.1111/j.1365-2427.2011.02649.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wakelin S. A., Colloff M. J., Kookana R. S. (2008). Effect of wastewater treatment plant effluent on microbial function and community structure in the sediment of a freshwater stream with variable seasonal flow. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 74 2659–2668 10.1128/AEM.02348-07 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Washington V. J., Lear G., Neale M. W., Lewis G. D. (2013). Environmental effects on biofilm bacterial communities: a comparison of natural and anthropogenic factors in New Zealand streams. Freshw. Biol. 58 2277–2286 10.1111/fwb.12208 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Webster J., Descals E. (1981). “Morphology, distribution and ecology of conidial fungi in freshwater habitats,” in Biology of Conidial Fungi, eds Cole G. C., Kendrick W. B. (New York: Academic Press; ), 295–355. [Google Scholar]

- Wey J. K., Jurgens K., Weitere M. (2012). Seasonal and successional influences on bacterial community composition exceed that of protozoan grazing in river biofilms. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 78 2013–2024 10.1128/AEM.06517-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitman W. B., Coleman D. C., Wiebe W. J. (1998). Prokaryotes: the unseen majority. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 95 6578–6583 10.1073/pnas.95.12.6578 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wymore A. S., Compson Z. G., Liu C. M., Price L. B., Whitham T. G., Keim P., et al. (2013). Contrasting rRNA gene abundance patterns for aquatic fungi and bacteria in response to leaf-litter chemistry. Freshw. Sci. 32 663–672 10.1899/12-122.1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yu R., Gan P., Mackay A. A., Zhang S. L., Smets B. F. (2010). Presence, distribution, and diversity of iron-oxidizing bacteria at a landfill leachate-impacted groundwater surface water interface. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 71 260–271 10.1111/j.1574-6941.2009.00797.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang M. L., Yu N., Chen L. Q., Jiang C. H., Tao Y. J., Zhang T., et al. (2012). Structure and seasonal dynamics of bacterial communities in three urban rivers in China. Aquat. Sci. 74 113–120 10.1007/s00027-011-0201-z [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zinger L., Gobet A., Pommier T. (2012). Two decades of describing the unseen majority of aquatic microbial diversity. Mol. Ecol. 21 1878–1896 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2011.05362.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zoppini A., Amalfitano S., Fazi S., Puddu A. (2010). Dynamics of a benthic microbial community in a riverine environment subject to hydrological fluctuations (Mulargia River, Italy). Hydrobiologia 657 37–51 10.1007/s10750-010-0199-6 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zwart G., Crump B. C., Agterveld M., Hagen F., Han S. K. (2002). Typical freshwater bacteria: an analysis of available 16S rRNA gene sequences from plankton of lakes and rivers. Aquat. Microbial. Ecol. 28 141–155 10.3354/ame028141 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.