ABSTRACT

Transforming growth factor beta (TGFbeta) superfamily signaling controls various aspects of female fertility. However, the functional roles of the TGFbeta-superfamily cognate signal transduction pathway components (e.g., SMAD2/3, SMAD4, SMAD1/5/8) in early embryonic development are not completely understood. We have previously demonstrated pronounced embryotrophic actions of the TGFbeta superfamily member-binding protein, follistatin, on oocyte competence in cattle. Given that SMAD4 is a common SMAD required for both SMAD2/3- and SMAD1/5/8-signaling pathways, the objectives of the present studies were to determine the temporal expression and functional role of SMAD4 in bovine early embryogenesis and whether embryotrophic actions of follistatin are SMAD4 dependent. SMAD4 mRNA is increased in bovine oocytes during meiotic maturation, is maximal in 2-cell stage embryos, remains elevated through the 8-cell stage, and is decreased and remains low through the blastocyst stage. Ablation of SMAD4 via small interfering RNA microinjection of zygotes reduced proportions of embryos cleaving early and development to the 8- to 16-cell and blastocyst stages. Stimulatory effects of follistatin on early cleavage, but not on development to 8- to 16-cell and blastocyst stages, were observed in SMAD4-depleted embryos. Therefore, results suggest SMAD4 is obligatory for early embryonic development in cattle, and embryotrophic actions of follistatin on development to 8- to 16-cell and blastocyst stages are SMAD4 dependent.

Keywords: cattle, embryo, follistatin, oocyte, SMAD4, TGFβ signaling

INTRODUCTION

Maternal RNAs and proteins, accumulated during oogenesis, are required for successful oocyte maturation, fertilization, zygotic genome activation, and early embryonic development, and hence functionally help determine oocyte competence [1]. In the past two decades, a growing list of maternal-effect genes has been identified that are essential for oocyte growth and development and embryo development using gene-targeting approaches in mice [2–4]. Because of intrinsic species differences in the duration and number of cell cycles required for embryonic genome activation and completion of the maternal-to-embryonic transition in livestock species, including cattle, and in humans, versus the mouse, the regulatory mechanisms and maternal-effect genes involved may not be identical. However, little information is known about the maternal regulation of early embryonic development, especially in nonrodent models [5, 6].

Initially, in an effort to identify genes associated with oocyte competence in cattle, we compared RNA transcript profiles of both oocyte and surrounding cumulus cells between good quality oocytes (adult) and poor quality oocytes using a prepubertal calf model of poor oocyte quality [7]. Analysis of the microarray data led to the discovery of follistatin as a differentially expressed gene that is overrepresented in the good oocytes relative to the poor quality oocytes. Moreover, we found follistatin mRNA was also higher in early cleaving 2-cell bovine embryos, which have a greater capacity to develop to blastocyst stage than their late-cleaving counterparts [7]. Functional results revealed treatment of early embryos with follistatin accelerates the time to first cleavage and improves rates of development to the blastocyst stage whereas the opposite effects are observed in response to small interfering RNA (siRNA)-mediated follistatin ablation in early embryos [8]. Collectively, our previous results suggest oocyte-derived follistatin is an important molecular determinant of oocyte competence in cattle. However, the molecular mechanisms underlying follistatin actions during early embryogenesis are unclear.

Follistatin was discovered based on its ability to inhibit FSH secretion via binding at a high affinity to inhibit activin activity [9]. To begin to determine if the positive effect of follistatin on early embryo development is mediated by inhibition of activin action, we previously tested the effect of exogenous activin and the effect of inhibition of signaling through type I receptor for activin, transforming growth factor β (TGFβ), and nodal (ALK 4, 5, and 7; SB-431542 inhibitor treatment) [10, 11] on bovine early embryonic development. The results revealed similar embryotrophic actions of activin on early cleavage and development to 8- to 16-cell and blastocyst stage whereas inhibition of activin, TGFβ, and nodal signaling with SB431542 was inhibitory to development. The results suggest that embryotrophic actions of follistatin are not mediated by inhibition of activin action [8].

Follistatin also binds to and regulates activity of additional members of the TGFβ superfamily beyond activin, including several BMPs [12, 13]. It is well known that TGFβ family members bind to type II receptors and recruit type I receptors, both of which are membrane-bound serine-threonine kinase receptors [14, 15]. The type I receptor is then phosphorylated and activated by type II receptor upon ligand binding. In turn, type I receptor phosphorylates receptor-activated SMADs (R-SMADs). Specifically, SMAD2/3 are phosphorylated in response to activin and TGFβ while SMAD1/5/8 are phosphorylated in response to BMP receptor binding. Upon phosphorylation, R-SMADs bind to the common SMAD (SMAD4) and translocate to the nucleus to regulate downstream gene transcription [15]. Therefore, we hypothesized that the positive actions of follistatin on bovine early embryogenesis may be mediated via regulation of specific SMAD2/3- and or SMAD1/5/8- dependent signaling pathways.

The objectives of the present study were to determine the functional role of SMAD4 in early embryonic development and if embryotrophic effects of follistatin are mediated through SMAD4 signaling. Initial emphasis was placed on SMAD4 because it is a common SMAD involved in both SMAD2/3- and SMAD1/5/8-signaling pathways [15]. The results revealed a functional role for SMAD4 in promoting early cleavage and development to 8- to 16-cell and blastocyst stages. The results also suggest that effects of follistatin on developmental progression to 8- to 16-cell and blastocyst stages are impeded in the absence of SMAD4, but follistatin effects on early cleavage are not affected.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials

Unless otherwise stated, all the chemicals and reagents were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich.

In Vitro Production of Bovine Embryos

Bovine oocyte maturation, in vitro fertilization (IVF), and embryo culture were performed according to procedures reported previously [8, 16]. In brief, cumulus-oocyte-complexes (COCs) containing more than three layers of compact cumulus cells and homogenous cytoplasm were obtained from 2- to 7-mm follicles from bovine ovaries that were collected at a slaughterhouse. COCs were matured in TCM 199 supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) (Hyclone), 5 international units/ml LH, 1 international unit/ml FSH (Sioux Biochemical), and 1 μg/ml estradiol-17β at 38.5°C under 5% CO2 in air. Upon maturation, COCs (50 COCs/well) were incubated with spermatozoa purified from frozen-thawed semen by Percoll gradient. IVF was performed at 38.5°C under 5% CO2 for 16–18 h. Putative zygotes were then removed of cumulus cells by vortexing for 5 min in hyaluronidase. Embryos were cultured in potassium simplex optimization medium (KSOM) (EMD Millipore) supplemented with 0.3% bovine serum albumin (BSA). Three days after fertilization, 8- to 16-cell embryos were separated, washed, and placed in fresh KSOM-containing wells containing 0.3% BSA and 10% FBS until Day 7.

Changes in Relative Abundance of SMAD4 mRNA During Oocyte Maturation and Early Embryogenesis

Germinal vesicle (GV) and MII-stage oocytes and putative zygotes, 2-cell, 4-cell, 8-cell, 16-cell, morula, and blastocyst-stage embryos were collected for RNA analysis as described previously [16]. Metaphase II-stage oocytes were collected 24 h after bovine oocyte maturation and putative zygotes were harvested at 20 h postinsemination (hpi), 2-cell embryos at 33 hpi, 4-cell embryos at 44 hpi, 8-cell embryos at 52 hpi, 16-cell embryos at 72 hpi, and morulas and blastocysts at 5 and 7 days postinsemination, respectively (n = 4 pools of 10 oocytes/embryos per pool/time point). For experiments to establish whether SMAD4 mRNA in early embryos is of maternal or zygotic origin, zygotes obtained were cultured as described above in KSOM containing 3 mg/ml BSA in the presence or absence of 50 μg/ml of the RNA polymerase II inhibitor α-amanitin and 8-cell embryos were collected 52 hpi.

RNA Interference in Early Embryos

RNA interference were performed according to our previous published work [5, 6, 8, 17]. Silencing of endogenous SMAD4 in bovine embryos was conducted via microinjection of SMAD4 siRNA. Two distinct siRNA species (designated as siRNA species 1 and 2, respectively) were designed targeting the coding sequence of SMAD4 mRNA by using the online siRNA design software (siRNA target finder; Ambion). The basic local alignment tool (BLAST) program was used for both siRNAs to rule out nonspecific targeting to other bovine genes, and siRNAs were produced by using the Silencer siRNA Construction Kit (Ambion) according to the manufacturer's instructions. The antisense and sense oligonucleotide template sequences for both siRNA species are as follows: siRNA 1-antisense: AACTGTTGTTTTTCGCTGCCTCCTGTCTC, sense: AAAGGCAGCGAAAAACAACAGCCTGTCTC; siRNA 2-antisense: AAGGGATTTCCTCATGTGATCCCTGTCTC, sense: AAGATCACATGAGGAAATCCCCCTGTCTC. Each siRNA species was tested for efficacy of SMAD4 mRNA knockdown in early embryos; 20 pl of siRNA (25 μM) was microinjected into putative zygotes collected at 16–18 hpi. Four-cell embryos were collected at 42–44 hpi for quantitative PCR analysis of SMAD4 mRNA abundance. Embryos that were uninjected and embryos injected with a universal negative control siRNA (universal negative control no. 1; Ambion) served as control groups (n = 4 pools of 10 embryos each per treatment). To determine the efficacy of SMAD4 siRNA in reducing SMAD4 protein in early embryos, immunostaining against SMAD4 was performed in 16-cell embryos collected 72 hpi (n = 10–15 embryos per group; described below). The developmental progression of the SMAD4 siRNA-injected embryos and control groups was monitored by recording the percentage of embryos that cleaved early (30 hpi), total cleavage rate (48 hpi), and the proportion of embryos developing to the 8- to 16-cell stage (72 hpi) and blastocyst stage (7 days after insemination).

To determine whether embryotrophic actions of follistatin are SMAD4 dependent, uninjected and SMAD4 siRNA-injected zygotes were subjected to embryo culture (as described above) in the presence or absence of maximal stimulatory dose of follistatin (10 ng/ml; control embryos; [8]) or increasing concentrations of follistatin (0, 1, 10, 100 ng/ml follistatin; SMAD4 siRNA-injected embryos) for the first 72 h of embryo culture; they were then follistatin-free until Day 7 (n = 25–30 embryos per treatment; n = 6 replicates). Effects of treatments on early cleavage, total cleavage rates, and percent development to 8- to 16-cell and blastocyst stages were determined as described above.

Immunofluorescence

Immunofluorescent localization of SMAD4 protein was performed according to procedures published previously [8]. Briefly, embryos were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS for 30 min. After washing three times in PBS, embryos were permeabilized with 0.1% Triton X-100 in PBS and blocked in solution containing 2% BSA and 10% normal goat serum in PBS for 1 h. Embryos were then incubated with primary antibody (mouse anti-SMAD4, 1:50 dilution; Santa Cruz Biotechnology). After three washes, embryos were treated with secondary antibody (anti-mouse IgG-Tritc, 1:100 dilution; Life Technologies) for 1 h. Finally, samples were mounted on slides using ProLong Gold Antifade Reagent with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (Life Technologies). Embryos that were incubated in the absence of anti-SMAD4 antibody were used as negative controls.

Reverse Transcription and Real-Time PCR

Total RNA extraction, cDNA synthesis, and quantitative real-time PCR (qPCR) were conducted according to procedures published previously with oligo dT primers used for quantification of the abundance of polyadenylated transcripts and random hexamers used for quantification of the abundance of total transcripts [8]. Sequence information for all the primers utilized can be found in Table 1. Relative mRNA abundance for genes of interest was calculated using the formula 2−ΔΔCT [18] with the mRNA abundance normalized to endogenous control (RPS18).

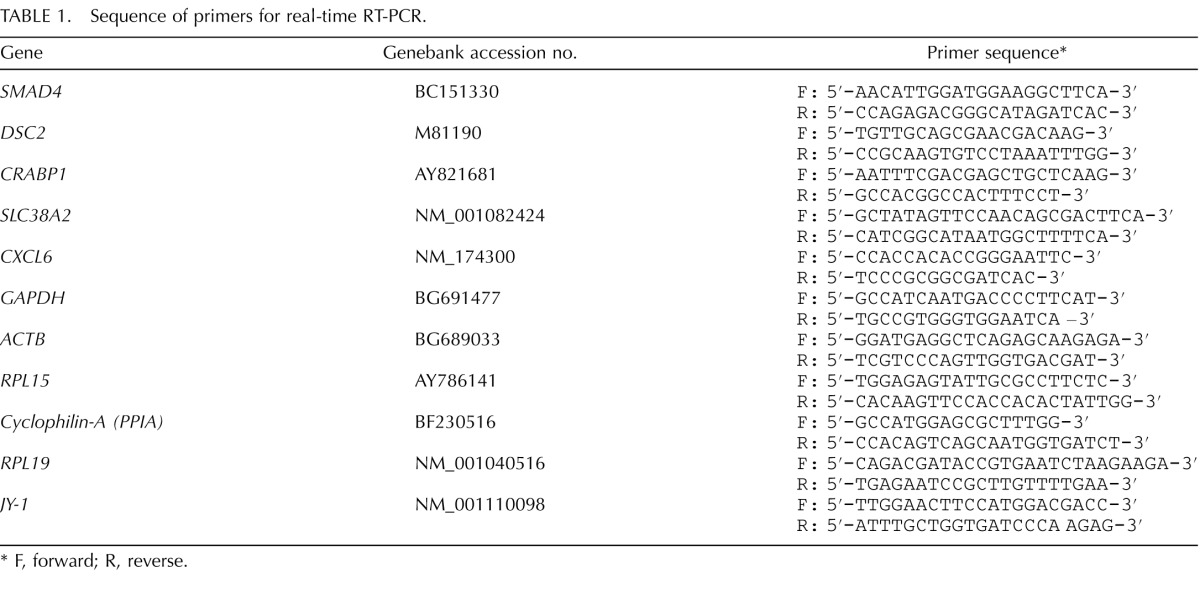

TABLE 1.

Sequence of primers for real-time RT-PCR.

F, forward; R, reverse.

Statistical Analysis

Data were analyzed using one-way ANOVA. All the percentage data for embryo culture experiments were calculated based on the number of zygotes cultured and were subjected to arc-sin transformation before analysis. Differences in treatment means were compared by using Fisher protected least significant difference test.

RESULTS

Expression Profile of SMAD4 mRNA in Bovine Early Embryos

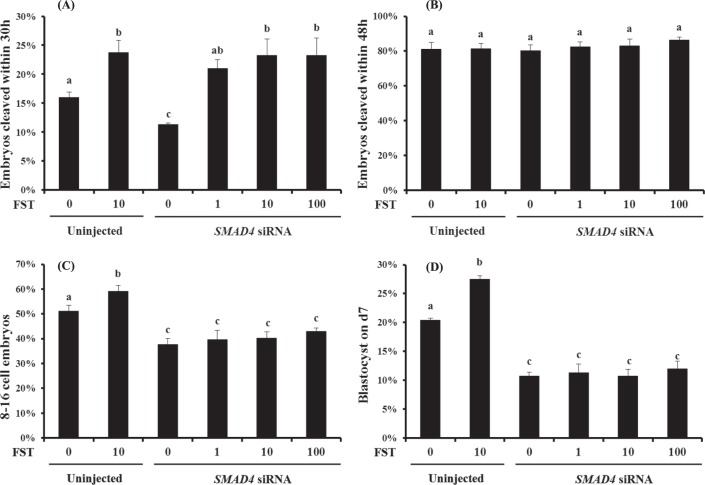

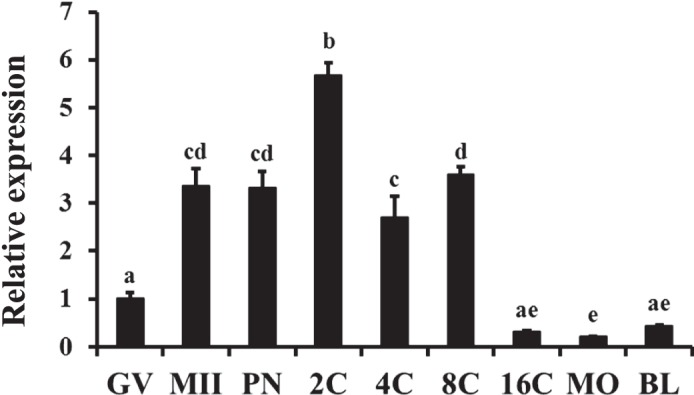

As shown in Figure 1, SMAD4 mRNA was detected throughout bovine early embryonic development. Polyadenylated transcripts for SMAD4 mRNA were present in GV oocytes, and their abundance was increased during meiotic maturation. Immediately after IVF, the abundance of such SMAD4 mRNA transcripts was transiently increased at the 2-cell stage but still remained elevated in the 4-cell and 8-cell embryos relative to the GV stage until the 16-cell stage, remaining low in the morula- and blastocyst-stage embryos. This dynamic gene expression pattern is reminiscent of maternal-effect genes. In order to test if SMAD4 mRNA was of maternal origin, putative zygotes were exposed to the RNA polymerase II inhibitor, α-amanitin, and qPCR analysis of SMAD4 mRNA abundance in embryos at the 8-cell stage was performed. As depicted in Figure 2A, an increase in SMAD4 mRNA abundance was observed in 8-cell embryos cultured in the presence of α-amanitin versus untreated controls. However, when RNA from control and α-amanitin-treated embryos was primed with random hexamers during cDNA synthesis (for quantification of total transcripts), no difference in SMAD4 mRNA abundance was detected (Fig. 2B). The results indicate that the SMAD4 mRNA in early embryos was of maternal origin, and the decline in SMAD4 mRNA near the time of embryonic genome activation was itself transcription dependent.

FIG. 1.

Temporal changes in SMAD4 mRNA abundance during oocyte maturation and early embryogenesis in vitro. Quantitative real-time PCR analysis of abundance of polyadenylated SMAD4 mRNA transcripts was performed on samples of germinal vesicle (GV) and metaphase II (MII) stage oocytes and in vitro derived embryos collected at the pronuclear (PN), 2-cell (2C), 4-cell (4C), 8-cell (8C), 16-cell (16C), morula (MO), and blastocyst (BL) stages (n = 4 pools of 10 oocytes/embryos per pool). Data were normalized relative to abundance of endogenous control (RPS18) and are shown as the mean ± SEM. Values with different superscripts across time points indicate significant differences (P < 0.05).

FIG. 2.

Effect of inhibition of transcription on SMAD4 mRNA abundance in 8-cell stage bovine embryos. Zygotes were cultured serum-free in KSOM supplemented with 0.3% BSA with or without 50 μg/ml of the RNA polymerase II inhibitor, α-amanitin. The 8-cell embryos were then collected (n = 4 pools of 10 embryos each per group) at 52 hpi for RNA isolation and real-time PCR analysis of SMAD4 mRNA. The RNA was primed with 1 μl of 100 μM oligo dT (A) or 1 μl of 20 μM random hexamers (B). Data were normalized relative to abundance of endogenous control (RPS18) and are shown as the mean ± SEM. Values with different superscripts across treatments indicate significant differences (P < 0.001).

Endogenous SMAD4 mRNA Is Efficiently and Specifically Knocked Down by RNA Interference

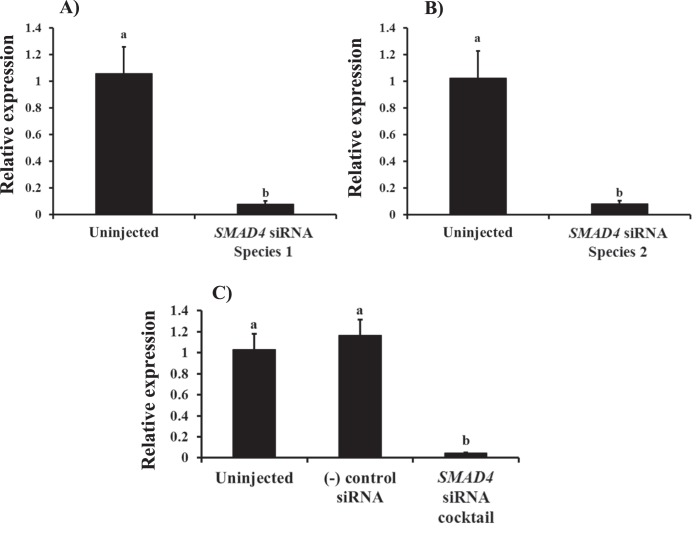

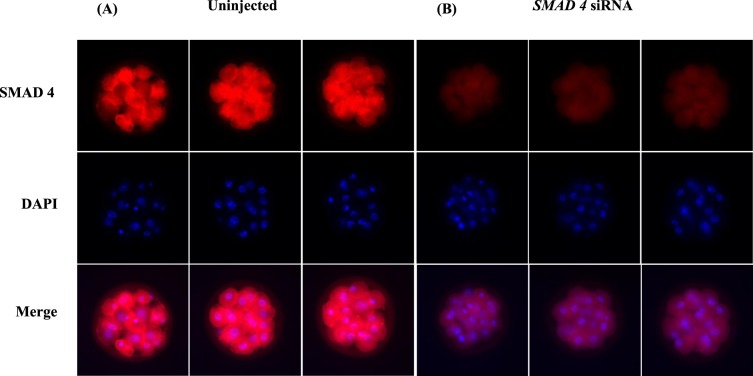

In order to determine the functional role of SMAD4 in early embryonic development in cattle, we first validated procedures for siRNA-mediated ablation of endogenous SMAD4 expression. As seen in Figure 3A–C, microinjection of SMAD4 siRNA species 1 and 2 individually or in combination greatly reduced endogenous SMAD4 mRNA abundance by >90% in bovine embryos collected at 42–44 hpi compared to negative control siRNA-injected and/or uninjected control embryos (P < 0.01). SMAD4 immunostaining studies revealed localization of SMAD4 protein in both the cytoplasm and nuclei of blastomeres and a significant reduction in SMAD4 staining in siRNA-injected embryos relative to control embryos (Fig. 4).

FIG. 3.

Validation of SMAD4 siRNA species for efficacy of SMAD4 mRNA knockdown in in vitro derived bovine embryos. Zygotes served as uninjected controls or were microinjected (16–18 hpi) with ∼20 pl of SMAD4 siRNA species 1 (25 μM; A), SMAD4 siRNA species 2 (25 μM; B), and either SMAD4 siRNA cocktail (25 μM; species 1 + 2) or universal negative control siRNA species 1 (25 μM; Ambion) (C). Four-cell stage embryos were collected at 42–44 hpi (n = 4 pools of 10 embryos each per treatment) for RNA isolation and real-time PCR analysis of SMAD4 mRNA. Data were normalized relative to abundance of endogenous control (RPS18) and are shown as the mean ± SEM. Values with different superscripts across treatments indicate significant differences (P < 0.01).

FIG. 4.

Demonstration of SMAD4 siRNA-mediated reduction in SMAD4 protein in bovine embryos. Zygotes were injected with SMAD4 siRNA (cocktail). SMAD4 siRNA treated and uninjected control embryos at the 16-cell stage were harvested 72 hpi and subjected to immunofluorescent localization of SMAD4 with 4′-6-diamidino-2-phenylindole staining used for visualization of nuclei. Representative confocal images of uninjected control (A) and SMAD4 siRNA (B) injected embryos are depicted (magnification ×400). Note the dramatic reduction in SMAD4 immunostaining in SMAD4 siRNA-injected embryos.

To further rule out the possibility of nonspecific recognition of target mRNAs, qPCR analysis was performed against several housekeeping genes (GAPDH, beta-actin, cyclophilin-A, ribosomal protein L-15 [RPL-15], and RPL-19) and the bovine oocyte-specific gene JY-1. As expected, mRNA abundance for all the above genes was similar between SMAD4 siRNA-injected embryos and control counterparts, further supporting specificity of SMAD4 siRNA in targeting SMAD4 mRNA in early embryos (Supplemental Fig. S1, available online at www.biolreprod.org).

Evidence that SMAD4 Is Required for Bovine Preimplantation Development

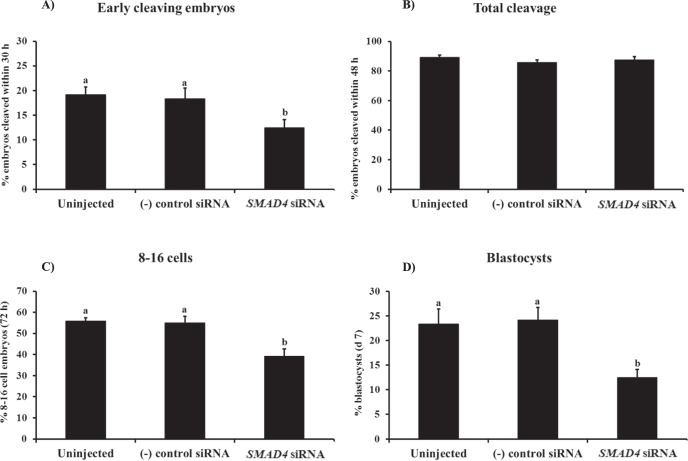

To determine if SMAD4 is required for bovine early embryonic development, putative zygotes generated by IVF were injected with SMAD4 siRNA and preimplantation development was monitored in terms of early cleavage, total cleavage, and development to the 8- to 16-cell and blastocyst stages. At 30 hpi, the proportion of embryos cleaving early was reduced in the SMAD4 siRNA-injected group relative to uninjected and negative control siRNA-injected embryos (P < 0.05, Fig. 5A) while the total cleavage rate (assessed at 48 hpi) was normal (Fig. 5B). However, the percentages of embryos developing to 8-to 16-cell stage (Fig. 5C) and blastocyst stage (Fig. 5D) were both decreased in response to SMAD4 siRNA injection relative to uninjected and negative control siRNA-injected embryos (P < 0.05).

FIG. 5.

Requirement of SMAD4 for bovine early embryonic development. Zygotes were microinjected (16–18 hpi) with either SMAD4 siRNA (cocktail), universal negative control siRNA species 1 (Ambion), or served as uninjected controls. Zygotes were then cultured in KSOM supplemented with 0.3% BSA (25–30 presumptive zygotes per group, 4 replicates). The 8- to 16-cell stage embryos were separated 72 hpi and cultured in fresh KSOM supplemented with 0.3% BSA and 10% FBS until Day 7. The effect of SMAD4 ablation on the proportion of embryos that reached the 2-cell stage within 30 hpi (early cleaving [A]), total cleavage rate (determined at 48 hpi [B]), proportion of embryos developing to the 8- to 16-cell stage (72 hpi [C]), and proportion of embryos developing to the blastocyst stage (Day 7 [D]) are shown. All the percentage data are expressed relative to the number of zygotes and are shown as the mean ± SEM. Values with different superscripts across treatments indicate significant differences (P < 0.05).

SMAD4 Is Required for Proper Expression of Markers of Zygotic Genome Activation

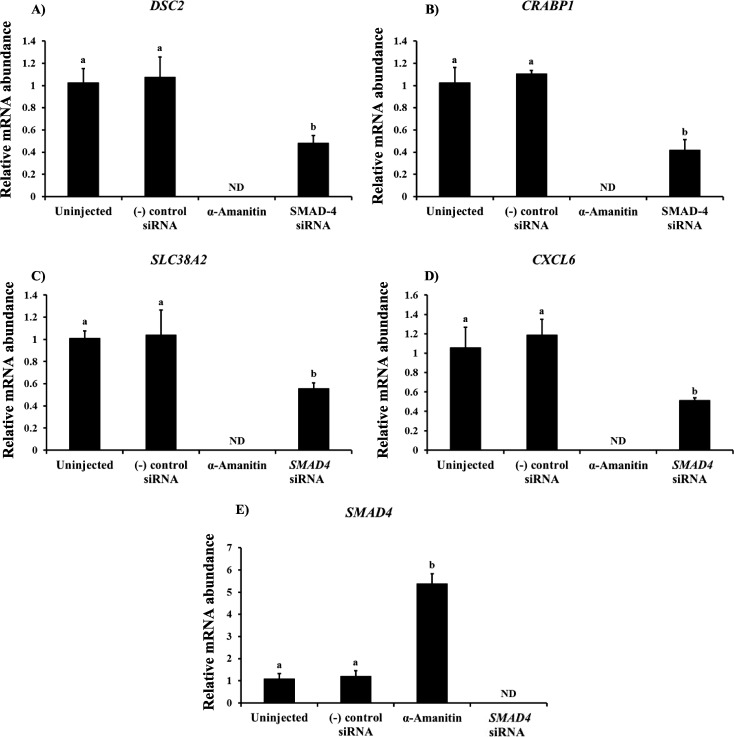

The expression pattern of SMAD4 mRNA in early embryos is reminiscent of genes involved in the maternal to embryonic transition. We and others have previously reported the catalog of zygotically expressed genes present in 8-cell stage bovine embryos [6, 19]. Thus, qPCR analysis for several known genes induced upon embryonic genome activation was performed (DSC2, CRABP1, SLC38A2, and CXCL6) on SMAD4 siRNA-treated and control embryos cultured in the presence or absence of α-amanitin. As shown in Figure 6, the mRNA abundance for the above transcripts was completely ablated in α-amanitin-treated embryos (Fig. 6A–D), confirming that the transcripts are zygotic in origin. Consistent with the results shown above, mRNA abundance for SMAD4 was decreased in response to siRNA injection and increased in control embryos cultured in the presence of α-amanitin (Fig. 6E; P < 0.05). Furthermore, SMAD4 siRNA injection decreased the abundance of DSC2, CRABP1, SLC38A2, and CXCL6 mRNAs in 8-cell bovine embryos relative to control embryos (Fig. 6A–D; P < 0.05). The results indicate that SMAD4 ablation affects zygotic genome activation as evidenced by reduced abundance of the above zygotic transcripts in 8-cell stage bovine embryos.

FIG. 6.

Effect of transcriptional inhibition via α-amanitin (RNA polymerase II inhibitor) treatment and/or SMAD4 siRNA injection on expression of zygotic transcripts in 8-cell stage bovine embryos. Quantification of mRNA for desmocollin 2 (DSC2 [A]), cellular retinoic acid-binding protein 1 (CRABP1 [B]), solute carrier family 38, member 2 (SLC38A2 [C]), chemokine (C-X-C motif) ligand 6 (CXCL6 [D]), and SMAD4 (E). Zygotes were microinjected (16–18 hpi) with ∼20 pl of SMAD4 siRNA (cocktail), universal negative control siRNA species 1 (Ambion), or served as uninjected controls and cultured serum-free in KSOM supplemented with 0.3% BSA and 50 μg/ml α-amanitin. The 8-cell embryos were collected 52 hpi (n = 4 pools of 10 embryos each per group) for RNA isolation and real-time RT-PCR analysis. Data were normalized relative to abundance of endogenous control (RPS18) and are shown as the mean ± SEM. Values with different superscripts across treatments indicate significant differences (P < 0.05). ND, not detected.

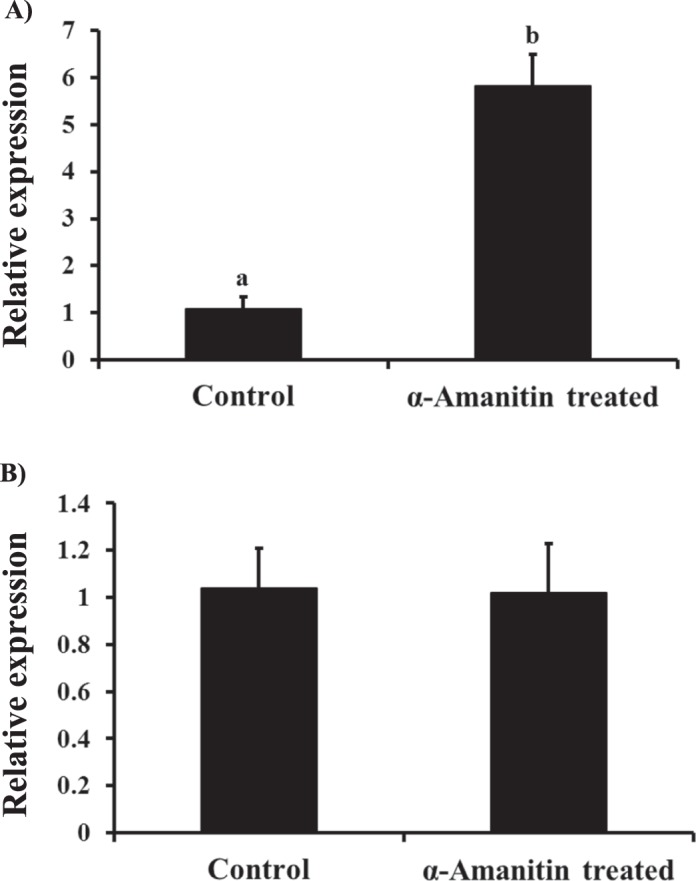

Effect of SMAD4 Ablation and Follistatin Supplementation on Bovine Early Embryonic Development

To determine if embryotrophic actions of follistatin are SMAD4 dependent, the effects of exogenous follistatin treatment of SMAD4-ablated embryos were determined. A reduction in the percent of embryos cleaving early and rates of development to the 8- to 16-cell and blastocyst stages were observed in SMAD4 siRNA-injected embryos as reported above, and the embryotrophic effects of maximal stimulatory dose of follistatin (10 ng/ml) were observed in uninjected control embryos (Fig. 7, A, C, and D; P < 0.05). Inhibitory effects of SMAD4 ablation on percent embryos cleaving early were reversed in a dose-dependent manner in response to treatment with increasing concentrations of follistatin (Fig. 7A). However, no effects of exogenous follistatin on percent development to 8- to 16-cell and blastocyst stages (Fig. 7, C and D) were observed when SMAD4 siRNA-injected embryos were treated with increasing concentrations of exogenous follistatin. The results suggest stimulatory effects of follistatin on development to 8- to 16-cell and blastocyst stages, but not early cleavage, are SMAD4 dependent.

FIG. 7.

Effect of SMAD4 ablation (siRNA microinjection) and/or follistatin supplementation on bovine early embryonic development. Zygotes were microinjected (16–18 hpi) with SMAD4 siRNA (cocktail) or served as uninjected controls. Uninjected and SMAD4 siRNA-injected zygotes were cultured serum-free in KSOM supplemented with 0.3% BSA and with or without 1–100 ng/ml follistatin (n = 25–30 zygotes per treatment; n = 6 replicates; 10 ng/ml dose only for uninjected embryos). The 8- to 16-cell stage embryos were then separated and cultured in fresh KSOM supplemented with 0.3% BSA and 10% FBS in the absence of exogenous follistatin until Day 7. The effect of SMAD4 ablation and/or follistatin supplementation on proportion of embryos that reached the 2-cell stage within 30 hpi (early cleaving [A]), total cleavage rate (determined 48 hpi [B]), proportion of embryos developing to the 8- to 16-cell stage (72 hpi [C]), and proportion of embryos developing to the blastocyst stage (Day 7 [D]) are shown. All the percentage data are expressed relative to the number of zygotes and are shown as the mean ± SEM. Values with different superscripts across treatments indicate significant differences (P < 0.05).

DISCUSSION

The functional role of TGFβ superfamily cognate signal transduction pathway components (e.g., SMAD2/3, SMAD4, SMAD1/5/8) in early embryogenesis is not well understood. The results of described studies demonstrated that SMAD4 of maternal origin is essential for bovine early embryonic development and revealed that specific actions of follistatin are dependent on SMAD4, the common SMAD involved in both SMAD2/3- and SMAD1/5/8-signaling pathways. To our knowledge, a functional requirement of SMAD signaling for early embryonic development has not been reported previously.

The TGFβ-SMAD-signaling pathway plays a wide-ranging role in the regulation of female fertility [20, 21]. A variety of components of the signaling pathway are present in ovarian cells, including oocytes, granulosa cells, and thecal cells [22–24]. Functional results from gene targeting studies in mice and molecular genetic studies in sheep indicate that select TGFβ family ligands and SMADs are critical for granulosa cell/follicle and/or oocyte development and function [25–29]. However, less is known about their expression profile and functional role in early embryos, particularly in cattle. The results of the present studies demonstrated that SMAD4 mRNA is elevated in maturated oocytes and remains elevated during early embryonic development until the 16-cell stage when transcript abundance decreases significantly. This window of early embryogenesis encompasses the time when the major wave of embryonic genomic activation occurs in cattle [30]. The results of embryo culture experiments in the presence of the transcriptional inhibitor, α-amanitin, and subsequent qPCR indicate that SMAD4 mRNA is of maternal origin and the decline in SMAD4 mRNA during embryo developmental progression is itself transcription dependent and likely mediated through transcript deadenylation. Adenylation and deadenylation of mRNAs are prominent mechanisms of regulation of mRNA abundance during oocyte maturation and early development until initiation of embryonic genome activation [31, 32]. Because removal of the polyA+ tail inhibits translation and is a starting point for RNA degradation [33], the results suggest that timely downregulation of maternal SMAD4 mRNA (as shown by the decrease in SMAD4 mRNA after the 16-cell stage) may potentially be significant to subsequent development after embryonic genome activation.

The specific maternal factors (primarily mRNA and protein) that play an essential role in directing early embryonic development, especially during the maternal-embryonic transition, when a subset of maternal mRNAs are decayed and embryonic genome transcription is initiated, are not completely understood [1, 32]. We tested whether SMAD4 is required for increased expression of select genes of zygotic origin in early embryos. Treatment with the transcription inhibitor, α-amanitin, blocked mRNA expression for selected zygotic transcripts (DSC2, CRABP1, SLC38A2, and CXCL6) previously identified from microarray analysis [6, 19], confirming that these mRNAs are transcribed from the zygotic genome and are not maternal in origin. In the SMAD4 siRNA-injected embryos, expression of these genes was decreased compared to control embryos, suggesting that SMAD4 ablation affects activation of the zygotic genome, at least at selected loci evaluated in the present study. Further research will be required to clarify if SMAD4 is required for genomewide transcriptional activation and to identify specific SMAD-dependent target genes of embryonic origin critical for further development.

Microinjection of SMAD4 siRNA into bovine zygotes resulted in a reduced proportion of embryos cleaving early (within 30 hpi) and poor rates of development to the blastocyst stage relative to controls, supporting a functional contribution of SMAD4 to bovine embryo developmental progression. While SMAD4 siRNA injection reduced the proportion of early cleaving embryos, no effects on total cleavage rates were observed. Likewise, maternal (oocyte derived) follistatin has been shown to affect early cleavage, but not total cleavage rates, in the current and previous studies [8]. Hence, the results suggest that TGFβ superfamily signaling potentially regulates the length of the first cell cycle but not ultimate ability of an embryo to cleave.

Previous studies of Smad4-null and -conditional knockout mice revealed an essential and potentially stage-specific role for Smad4 in embryonic development. Crossing of mice heterozygous for Smad4-null allele demonstrated that resulting embryos homozygous null for Smad4 allele display postimplantation lethality by Embryonic Day 7.5 and a defect in gastrulation [34]. Such results may mean, relative to the bovine model system, that the requirement for Smad4 is manifest later in development in the mouse and/or maternal Smad4 is sufficient to promote preimplantation early embryonic development in the mouse. However, oocyte-specific deletion of Smad4 in mice using ZP3 promoter driving CRE recombinase or GDF9 promoter driving CRE recombinase has no effect on fertility or causes a very small reduction in litter size, respectively [35]. Hence, the results suggest a potential species-specific role (unique from the mouse) for maternal (oocyte derived) SMAD4 in promoting initial stages of bovine early embryogenesis.

Further examination of our results in the bovine model system revealed that the reduced blastocyst rate results from both reduced development to 8- to 16-cell stage and reduced development from the 8- to 16-cell to the blastocyst stage. This result suggests SMAD4 is a critical player throughout the entire period of in vitro early embryonic development in cattle. The poor development during the first 3 days (prior to embryonic genome activation) may potentially be accounted for by the disruption of the maternal-embryonic transition (e.g., reduced expression of selected zygotic-expressed genes in SMAD4-deficient embryos). However, Smad4-null mutant mouse embryos also display reduced cell proliferation at Embryonic Day 6.5 [34]. Hence, the direct effects of SMAD4 knockdown on cell cycle kinetics in bovine embryos also cannot be discounted, particularly because SMAD4 knockdown causes a reduction in percentage of embryos cleaving early.

Our previous studies demonstrated an intrinsic embryotrophic role of follistatin in enhancing multiple aspects of preimplantation early embryonic development in cattle, including the proportion of embryos cleaving early and the rates of development to 8- to 16-cell and blastocyst stages. Follistatin is a binding protein for specific members of the TGFβ superfamily and may exert its embryotrophic effects through modulation of one or more of the SMAD (SMAD2/3, SMAD1/5) or non-SMAD (e.g., AKT, JNK, ERK, and P38) signaling pathways regulated by TGFβ superfamily members [36]. To further investigate the mechanism of action of follistatin, we tested whether the actions of follistatin are affected in SMAD4-deficient embryos. The results demonstrated a significant reduction in proportion of embryos cleaving early in response to SMAD4 siRNA injection, but the percentage of early cleaving embryos in response to follistatin treatment was increased in a similar fashion for both SMAD4 siRNA-injected and control embryos. This suggests that the effects of follistatin in accelerating the time to first cleavage are potentially independent of the actions of SMAD4 and hence presumably mediated by SMAD-independent pathways linked to TGFβ superfamily signaling [37].

The mechanisms involved in follistatin and SMAD4 regulation of time to first cleavage and the specific stages of the first cell cycle that are accelerated are not clear. Previous studies revealed that there is significant variability in length of all cell cycle components in human zygotes after sperm penetration [38]. In general, members of the TGFβ superfamily have pleiotropic and cell-specific actions in promoting cell proliferation versus differentiation [39]. For example, activin treatment induces cell cycle arrest in cells of B-cell lineage via triggering hypophosphorylation of the retinoblastoma protein [40], whereas we have shown that activin A treatment of bovine embryos actually accelerates the time to first cleavage and results in a greater proportion of early cleaving embryos [8]. Further investigation will be required to determine the specific follistatin-regulated SMAD4-independent signaling pathways that lead to accelerated time to first cleavage in early bovine embryos. Regardless, increased understanding of regulation of the first cleavage division is of practical significance to assisted reproductive technologies (ART) in cattle and humans. After IVF, early cleaving bovine [7, 41] and human embryos [42, 43] have enhanced capacity to reach the blastocyst stages as compared to their later cleaving counterparts. Furthermore, time to first cleavage is a significant predictor of embryo developmental potential and success of ART in humans, with >2-fold higher pregnancy rates observed in single embryo transfers of early cleaving embryos versus later cleaving embryos [44–46].

In contrast to observed SMAD4-independent actions of follistatin in accelerating time to first cleavage, culture of SMAD4 siRNA-injected embryos with increasing concentrations of follistatin (1, 10, and 100 ng/ml) did not rescue the inhibitory effects of SMAD4 knockdown on development to the 8- to 16-cell and blastocyst stages, suggesting that these specific embryotrophic actions of follistatin are in fact SMAD4 dependent. Our previous studies demonstrated stimulatory effects of exogenous activin treatment on rates of development of bovine embryos to the 8- to 16-cell and blastocyst stages, suggesting the presence of a functional SMAD2/3-signaling pathway in bovine embryos [8]. Further investigation will be required to determine whether SMAD4-dependent embryotrophic actions of follistatin are mediated through regulation of activity of SMAD2/3- and/or SMAD1/5/8-dependent pathways in bovine embryos and the accompanying specific ligands whose activity follistatin regulates.

In conclusion, our results suggest that SMAD4 is an important intracellular signaling molecule required for bovine early embryogenesis. The results also suggest that embryotrophic actions of follistatin on early cleavage, but not development to 8- to 16-cell and blastocyst stages, are SMAD4 independent. Increased understanding of the intrinsic signaling pathways and molecules linked to successful early embryogenesis is critical to future improvements in ART and further understanding of factors potentially contributing to infertility in cattle and humans.

Footnotes

Supported by the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development of the National Institutes of Health under award number R01HD072972 and by Michigan State University AgBioResearch.

These authors contributed equally to this work.

REFERENCES

- Li L, Zheng P, Dean J. Maternal control of early mouse development. Development. 2010;137:859–870. doi: 10.1242/dev.039487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng P, Dean J. Role of Filia, a maternal effect gene, in maintaining euploidy during cleavage-stage mouse embryogenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:7473–7478. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0900519106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu X, Viveiros MM, Eppig JJ, Bai Y, Fitzpatrick SL, Matzuk MM. Zygote arrest 1 (Zar1) is a novel maternal-effect gene critical for the oocyte-to-embryo transition. Nat Genet. 2003;33:187–191. doi: 10.1038/ng1079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tong ZB, Gold L, Pfeifer KE, Dorward H, Lee E, Bondy CA, Dean J, Nelson LM. Mater, a maternal effect gene required for early embryonic development in mice. Nat Genet. 2000;26:267–268. doi: 10.1038/81547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bettegowda A, Yao J, Sen A, Li Q, Lee KB, Kobayashi Y, Patel OV, Coussens PM, Ireland JJ, Smith GW. JY-1, an oocyte-specific gene, regulates granulosa cell function and early embryonic development in cattle. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:17602–17607. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0706383104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tripurani SK, Lee KB, Wang L, Wee G, Smith GW, Lee YS, Latham KE, Yao J. A novel functional role for the oocyte-specific transcription factor newborn ovary homeobox (NOBOX) during early embryonic development in cattle. Endocrinology. 2011;152:1013–1023. doi: 10.1210/en.2010-1134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel OV, Bettegowda A, Ireland JJ, Coussens PM, Lonergan P, Smith GW. Functional genomics studies of oocyte competence: evidence that reduced transcript abundance for follistatin is associated with poor developmental competence of bovine oocytes. Reproduction. 2007;133:95–106. doi: 10.1530/rep.1.01123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee KB, Bettegowda A, Wee G, Ireland JJ, Smith GW. Molecular determinants of oocyte competence: potential functional role for maternal (oocyte-derived) follistatin in promoting bovine early embryogenesis. Endocrinology. 2009;150:2463–2471. doi: 10.1210/en.2008-1574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakamura T, Takio K, Eto Y, Shibai H, Titani K, Sugino H. Activin-binding protein from rat ovary is follistatin. Science. 1990;247:836–838. doi: 10.1126/science.2106159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inman GJ, Nicolas FJ, Callahan JF, Harling JD, Gaster LM, Reith AD, Laping NJ, Hill CS. SB-431542 is a potent and specific inhibitor of transforming growth factor-beta superfamily type I activin receptor-like kinase (ALK) receptors ALK4, ALK5, and ALK7. Mol Pharmacol. 2002;62:65–74. doi: 10.1124/mol.62.1.65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laping NJ, Grygielko E, Mathur A, Butter S, Bomberger J, Tweed C, Martin W, Fornwald J, Lehr R, Harling J, Gaster L, Callahan JF et al. Inhibition of transforming growth factor (TGF)-beta1-induced extracellular matrix with a novel inhibitor of the TGF-beta type I receptor kinase activity: SB-431542. Mol Pharmacol. 2002;62:58–64. doi: 10.1124/mol.62.1.58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glister C, Kemp CF, Knight PG. Bone morphogenetic protein (BMP) ligands and receptors in bovine ovarian follicle cells: actions of BMP-4, -6 and -7 on granulosa cells and differential modulation of Smad-1 phosphorylation by follistatin. Reproduction. 2004;127:239–254. doi: 10.1530/rep.1.00090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balemans W, Van Hul W. Extracellular regulation of BMP signaling in vertebrates: a cocktail of modulators. Dev Biol. 2002;250:231–250. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myers M, Pangas SA. Regulatory roles of transforming growth factor beta family members in folliculogenesis. Wiley interdisciplinary reviews. Syst Biol Med. 2010;2:117–125. doi: 10.1002/wsbm.21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiss A, Attisano L. The TGFbeta superfamily signaling pathway. Wiley Interdiscip Rev Dev Biol. 2013;2:47–63. doi: 10.1002/wdev.86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bettegowda A, Patel OV, Ireland JJ, Smith GW. Quantitative analysis of messenger RNA abundance for ribosomal protein L-15, cyclophilin-A, phosphoglycerokinase, beta-glucuronidase, glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase, beta-actin, and histone H2A during bovine oocyte maturation and early embryogenesis in vitro. Mol Reprod Dev. 2006;73:267–278. doi: 10.1002/mrd.20333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tejomurtula J, Lee KB, Tripurani SK, Smith GW, Yao J. Role of importin alpha8, a new member of the importin alpha family of nuclear transport proteins, in early embryonic development in cattle. Biol Reprod. 2009;81:333–342. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.109.077396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) method. Methods. 2001;25:402–408. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Misirlioglu M, Page GP, Sagirkaya H, Kaya A, Parrish JJ, First NL, Memili E. Dynamics of global transcriptome in bovine matured oocytes and preimplantation embryos. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:18905–18910. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0608247103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edson MA, Nagaraja AK, Matzuk MM. The mammalian ovary from genesis to revelation. Endocrine Rev. 2009;30:624–712. doi: 10.1210/er.2009-0012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richards JS, Pangas SA. The ovary: basic biology and clinical implications. J Clin Investig. 2010;120:963–972. doi: 10.1172/JCI41350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tian X, Halfhill AN, Diaz FJ. Localization of phosphorylated SMAD proteins in granulosa cells, oocytes and oviduct of female mice. Gene Expr Patterns. 2010;10:105–112. doi: 10.1016/j.gep.2010.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu J, Oakley J, McGee EA. Stage-specific expression of Smad2 and Smad3 during folliculogenesis. Biol Reprod. 2002;66:1571–1578. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod66.6.1571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osterlund C, Fried G. TGFbeta receptor types I and II and the substrate proteins Smad 2 and 3 are present in human oocytes. Mol Hum Reprod. 2000;6:498–503. doi: 10.1093/molehr/6.6.498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elvin JA, Yan C, Matzuk MM. Oocyte-expressed TGF-beta superfamily members in female fertility. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2000;159:1–5. doi: 10.1016/s0303-7207(99)00185-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang H, Matzuk MM. Smad5 is required for mouse primordial germ cell development. Mech Dev. 2001;104:61–67. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4773(01)00367-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richards JS, Pangas SA. The ovary: basic biology and clinical implications. J Clin Invest. 2010;120:963–972. doi: 10.1172/JCI41350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galloway SM, Gregan SM, Wilson T, McNatty KP, Juengel JL, Ritvos O, Davis GH. Bmp15 mutations and ovarian function. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2002;191:15–18. doi: 10.1016/s0303-7207(02)00047-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNatty KP, Smith P, Moore LG, Reader K, Lun S, Hanrahan JP, Groome NP, Laitinen M, Ritvos O, Juengel JL. Oocyte-expressed genes affecting ovulation rate. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2005;234:57–66. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2004.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Memili E, First NL. Zygotic and embryonic gene expression in cow: a review of timing and mechanisms of early gene expression as compared with other species. Zygote. 2000;8:87–96. doi: 10.1017/s0967199400000861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bettegowda A, Smith GW. Mechanisms of maternal mRNA regulation: implications for mammalian early embryonic development. Front Biosci. 2007;12:3713–3726. doi: 10.2741/2346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bettegowda A, Lee KB, Smith GW. Cytoplasmic and nuclear determinants of the maternal-to-embryonic transition. Reprod Fertil Dev. 2008;20:45–53. doi: 10.1071/rd07156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guhaniyogi J, Brewer G. Regulation of mRNA stability in mammalian cells. Gene. 2001;265:11–23. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(01)00350-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sirard C, de la Pompa JL, Elia A, Itie A, Mirtsos C, Cheung A, Hahn S, Wakeham A, Schwartz L, Kern SE, Rossant J, Mak TW. The tumor suppressor gene Smad4/Dpc4 is required for gastrulation and later for anterior development of the mouse embryo. Genes Dev. 1998;12:107–119. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.1.107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X, Tripurani SK, James R, Pangas SA. Minimal fertility defects in mice deficient in oocyte-expressed Smad4. Biol Reprod. 2012;86:1–6. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.111.094375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamato D, Burch ML, Piva TJ, Rezaei HB, Rostam MA, Xu S, Zheng W, Little PJ, Osman N. Transforming growth factor-beta signalling: role and consequences of Smad linker region phosphorylation. Cell Signal. 2013;25:2017–2024. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2013.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mu Y, Gudey SK, Landstrom M. Non-Smad signaling pathways. Cell Tissue Res. 2012;347:11–20. doi: 10.1007/s00441-011-1201-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagy ZP, Janssenswillen C, Janssens R, De Vos A, Staessen C, Van de Velde H, Van Steirteghem AC. Timing of oocyte activation, pronucleus formation and cleavage in humans after intracytoplasmic sperm injection (ICSI) with testicular spermatozoa and after ICSI or in-vitro fertilization on sibling oocytes with ejaculated spermatozoa. Hum Reprod. 1998;13:1606–1612. doi: 10.1093/humrep/13.6.1606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitisin K, Saha T, Blake T, Golestaneh N, Deng M, Kim C, Tang Y, Shetty K, Mishra B, Mishra L. Tgf-Beta signaling in development. Sci STKE. 2007;2007:cm1. doi: 10.1126/stke.3992007cm1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zauberman A, Oren M, Zipori D. Involvement of p21(WAF1/Cip1), CDK4 and Rb in activin A mediated signaling leading to hepatoma cell growth inhibition. Oncogene. 1997;15:1705–1711. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1201348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lonergan P, Rizos D, Gutierrez-Adan A, Fair T, Boland MP. Oocyte and embryo quality: effect of origin, culture conditions and gene expression patterns. Reprod Domest Anim. 2003;38:259–267. doi: 10.1046/j.1439-0531.2003.00437.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakkas D, Shoukir Y, Chardonnens D, Bianchi PG, Campana A. Early cleavage of human embryos to the two-cell stage after intracytoplasmic sperm injection as an indicator of embryo viability. Hum Reprod. 1998;13:182–187. doi: 10.1093/humrep/13.1.182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shoukir Y, Chardonnens D, Campana A, Bischof P, Sakkas D. The rate of development and time of transfer play different roles in influencing the viability of human blastocysts. Hum Reprod. 1998;13:676–681. doi: 10.1093/humrep/13.3.676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards RG, Fishel SB, Cohen J, Fehilly CB, Purdy JM, Slater JM, Steptoe PC, Webster JM. Factors influencing the success of in vitro fertilization for alleviating human infertility. J In Vitro Fert Embryo Transf. 1984;1:3–23. doi: 10.1007/BF01129615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salumets A, Hyden-Granskog C, Makinen S, Suikkari AM, Tiitinen A, Tuuri T. Early cleavage predicts the viability of human embryos in elective single embryo transfer procedures. Hum Reprod. 2003;18:821–825. doi: 10.1093/humrep/deg184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Montfoort AP, Dumoulin JC, Kester AD, Evers JL. Early cleavage is a valuable addition to existing embryo selection parameters: a study using single embryo transfers. Hum Reprod. 2004;19:2103–2108. doi: 10.1093/humrep/deh385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]