Abstract

A trichobezoar is an immobile, indigestible collection of hair or hair-like fibers that accumulates within the GI tract. Rapunzel syndrome is a rare variant in which a trichobezoar extends into the small intestine, potentially causing obstruction. We describe the first case, to our knowledge, of Rapunzel syndrome occurring in a postpartum patient after delivery by Caesarian section.

Introduction

A trichobezoar is an immobile, indigestible collection of hair or hair-like fibers that accumulates within the GI tract. The first reported case of trichobezoar was by Baudamant in 1779.1 Trichobezoar is typically the result of trichotillomania and trichophagia, or the pulling and eating of one's own hair. Rapunzel syndrome is a rare variant in which a trichobezoar extends into the small intestine, potentially causing obstruction. We describe the first case, to our knowledge, of Rapunzel syndrome occurring in a postpartum patient after delivery by Caesarian section.

Case Report

A 27-year-old woman presented to the hospital with acute onset of abdominal pain, nausea, and vomiting for 1 day. The patient was recently pregnant, and underwent uncomplicated Caesarian delivery 2 months prior to presentation. The patient suffered from chronic abdominal pain, nausea, and vomiting throughout her pregnancy, and required multiple admissions to the hospital during her pregnancy for what was thought to be hyperemesis gravidarum. Two weeks following delivery, the patient was again admitted for severe abdominal pain, nausea, and vomiting. Evaluation at that time included a CT scan of the abdomen showing a large amount of heterogeneous material in the stomach (thought to be recently ingested food), a new umbilical hernia, and no other abnormalities. The patient was discharged home after evaluation by surgical services. The patient described her current symptoms as being similar to those she had throughout her pregnancy and in the 2 weeks after her delivery.

Her past medical history was significant for a gunshot wound to the face 1 year prior, requiring multiple facial surgeries and resulting in chronic opioid dependence. She had recently been weaned off opioids, and her chronic medications at home included naltrexone, ibuprofen as needed for pain, and promethazine as needed for nausea. The patient had 2 other young children from whom she was estranged. On physical exam, the patient appeared nervous and anxious and was hiding underneath the blankets in her hospital bed. Her abdomen was markedly tender to palpation in the epigastrum and right upper quadrant with no palpable masses. Laboratory testing was unremarkable. CT of the abdomen again showed a large amount of material in the gastric lumen with gastric distension (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Computed tomography image of trichobezoar.

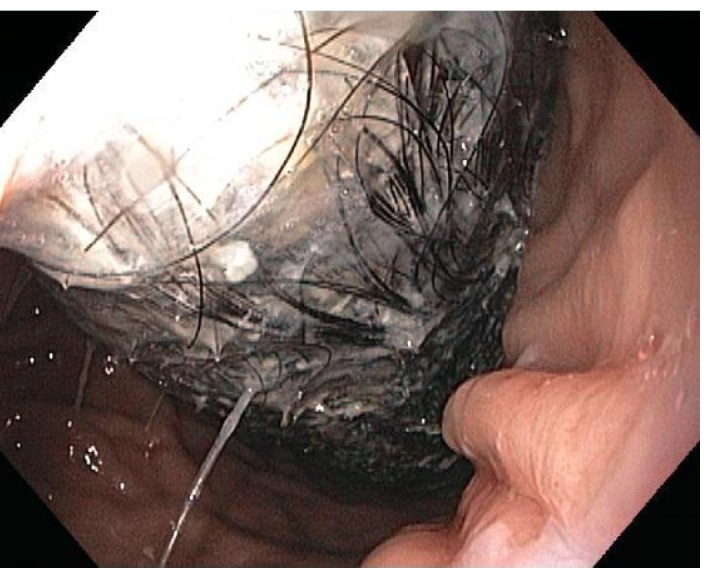

Upper endoscopy revealed hair in the oropharynx and esophagus, and a large trichobezoar filling the entire stomach that prevented passage of the endoscope beyond the proximal gastric body (Figure 2). Due to the size and nature of the trichobezoar, general surgery was consulted for surgical resection. The patient underwent laparotomy with gastrotomy and removal of the trichobezoar, which was described by the surgeons as a cast of the entire stomach made entirely of hair that extended partially into the duodenum. The specimen removed measured 23.0 × 6.0 × 5.0 cm (Figure 3).

Figure 2.

Endoscopic image of trichobezoar.

Figure 3.

Surgical specimen of trichobezoar.

The patient admitted that she had been ritualistically eating her own hair for the last 6 years, and had been seeing a therapist as an outpatient with poor follow-up.

Discussion

Only 2 cases of Rapunzel syndrome occurring during the peurperium have been reported to date: one occurring in the second trimester, and one after spontaneous vaginal delivery.2,3 We describe the third known case of Rapunzel syndrome occurring in the peurperium, and the first such case diagnosed after Caesarian section delivery. The significance of the patient's Caesarian delivery is that her recent surgery provided one more attributable cause of her abdominal pain. The layered history of a recent pregnancy, recent surgery, and complex social history provided several possible explanations for her symptoms. As a result, it took multiple presentations to the emergency department before it became clear that further investigation was necessary. The emotional and physical stress of pregnancy, Caesarian delivery, and care for a new infant likely exacerbated the patient's trichotillomania and trichophagia to the point that the ingested hairs accumulated and ultimately impacted in her upper digestive tract.

Human hair is resistant to digestion and peristalsis due to its smooth surface. When hair is ingested, it accumulates between mucosal folds in the stomach. With the aid of peristalsis, the strands of hair can become entwined to form a mesh. Over time, continued ingestion of hair leads to impaction mixed with mucus and food, forming a trichobezoar, which ultimately takes the shape of the stomach. Trichobezoars form in only 1% of patients who have trichotillomania with trichophagia.4 The diagnosis is most common in young women and children. Typically, patients have an underlying psychiatric disorder, mental retardation, or pica.5,6 Carpet and clothing fiber can also accumulate in the GI tract and form trichobezoars if ingested in large amounts.6

Rapunzel syndrome is a rare variant in which a trichobezoar extends past the pylorus and into the small intestine. It is named after the enchanting German fairy tale of Rapunzel, written by the Brothers Grimm in 1812. Rapunzel had hair so long that she could lower it down to her prince from high up in her prison tower to allow him to climb up to her window and rescue her.7 Similarly, there are reported cases of Rapunzel syndrome with trichobezoars extending as distal as the transverse colon.7

Gastroparesis is a risk factor for developing gastric bezoars. Patients with diabetes, end-stage renal disease, prior gastric surgery, and patients on mechanical ventilation are all at greater risk for bezoar formation.6 Patients typically present with abdominal pain (37%), nausea and vomiting (33.3%), obstruction (25.9%), or peritonitis (18.3%).7 Physical exam may reveal a palpable abdominal mass. Diagnosis of trichobezoar is best screened by imaging modalities such as CT scan, and is best confirmed by upper endoscopy. Small trichobezoars may be managed conservatively, but larger trichobezoars are best managed by laparotomy with gastrotomy and removal.8 Complications of trichobezoar and Rapunzel syndrome include ulceration or perforation of the stomach or intestine, intussusception, small bowel obstruction, jaundice, and even pancreatitis due to obstruction at the ampulla of Vater.6,8

Trichobezoar is a rare diagnosis that should be considered in patients with nonspecific abdominal pain, nausea, and vomiting, especially in young women with prior or suspected concurrent psychiatric diagnoses. Trichobezoar should also be considered in the differential diagnosis for a pregnant woman with abdominal pain, intractable nausea, and vomiting. Effective communication and a good relationship between the patient and medical provider are essential in making an early diagnosis of trichobezoar. Preventing recurrence is just as important as active treatment of trichobezoar. Patients diagnosed with trichobezoar should have close followup with psychiatry post-operatively to prevent recurrence. Parental or spousal counseling may be beneficial. Follow-up endoscopy or contrast study may be indicated if symptoms recur, or if trichotillomania and trichophagia is suspected.7 Patients may deny persistent or recurrent trichotillomania and trichophagia, which is all the more reason to establish a strong relationship with such patients early on.

Disclosures

Author contributions: DJ Andrade was primary author, W. Dabbs was secondary author, and V. Honan was principal investigator and is the article guarantor.

Financial disclosure: No authors have financial disclosures.

Informed consent was obtained for this case report.

References

- 1.Santos T, Nuno M, Joao A, et al. Trichophagia and trichobezoar: Case report. Clin Pract Epidemiol Ment Health. 2012;8:43–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Salem M, Fouda R, Fouda U, Maadawy ME, Ammar H. Rapunzel and pregnancy. South Med J. 2009;102(1):106–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rabie ME, Arishi AR, Khan A, et al. Rapunzel syndrome: The unsuspected culprit. World J Gastroenterol. 2008;14(7):1141–1143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Prasad AJ, Rizvon KM, Angus G, et al. A giant trichobezoar presenting as an abdominal mass. Gastrointest Endosc. 2011;73(5):1052–1054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Singla SL, Rattan KN, Kaushik N, Pandit SK. Rapunzel syndrome: A case report. Am J Gastroenterol. 1999;94(7):1970–1971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Feldman M, Friedman LS, Brandt LJ. Foreign bodies, bezoars, and caustic ingestions In: Sleisenger and Fordtran's Gastrointestinal and Liver Disease. 9th ed.Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Naik S, Gupta V, Naik S, et al. Rapunzel syndrome reviewed and redefined. Dig Surg. 2007;24:157–161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gorter RR, Kneepkens CM, Mattens EC, et al. Management of trichobezoar: Case report and literature review. Pediatr Surg Int. 2010;26:457–463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]