Abstract

Olmesartan sprue-like enteropathy is an adverse drug reaction that mimics the appearance of celiac disease and is related to the use of olmesartan. We present the case of a 71-year-old female with severe enteropathy attributed to celiac disease for 5 years that improved only after valsartan cessation. This is the first case associating valsartan with sprue-like enteropathy.

Introduction

Olmesartan is an angiotensin II receptor blocker (ARB) commonly used to treat hypertension, heart failure, and kidney disease.1 Severe enteropathy has been associated with olmesartan use.2-6 This adverse drug reaction has led the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to issue a statement on olmesartan labeling.7-9 Valsartan, another ARB,10 has not been implicated in sprue-like enteropathy prior to this report.

Case Report

A 71-year-old woman with rheumatoid arthritis, hypothyroidism, and psoriasis presented with a 5-year history of refractory sprue and severe malabsorption. Her symptoms began with the sudden onset of nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea. Her nausea and vomiting improved initially, but she continued to have intermittent watery and malodorous diarrhea, nighttime fecal incontinence, abdominal pain, and a 27-kg weight loss. Celiac disease was suspected based on duodenal and jejunal biopsies showing complete villous atrophy, intraepithelial lymphocytosis, and crypt hyperplasia (Figure 1). Capsule endoscopy showed scalloping, blunted villi, and extensive villous atrophy in 75-90% of the small intestine, based on time (Figure 2). Celiac serologies were negative while consuming gluten. She had persistent symptoms despite strict adherence to a gluten-free diet.

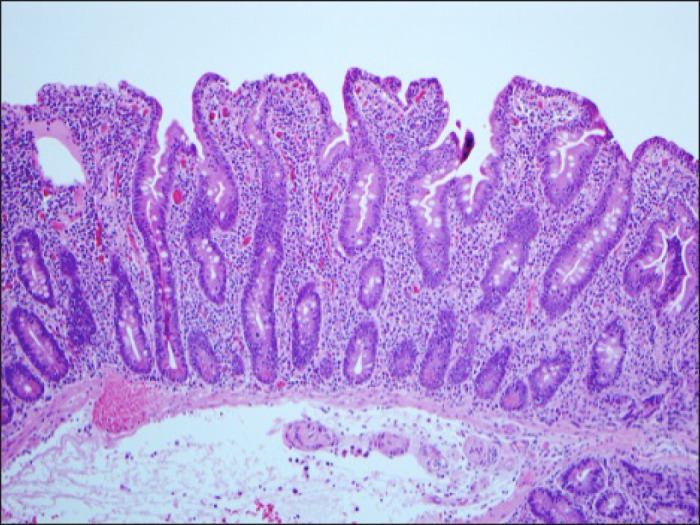

Figure 1.

Small bowel biopsy on valsartan and a gluten-free diet for 5 years showing a malabsorption pattern with partial villous atrophy, with crypt hyperplasia and inflammation with 100 intraepithelial lymphocytes per 100 epithelial cells.

Figure 2.

Fissuring and scalloping with blunted villi shown on capsule endoscopy. Extensive villous atrophy affecting approximately 75-90% of the small intestinal mucosa based on time.

She had a body mass index (BMI) of 19 kg/m2 with significant muscle wasting and minimal adipose tissue. Otherwise, exam was notable for hyperactive bowel sounds and bilateral pitting lower extremity edema. Laboratory evaluation showed evidence of malabsorption: hemoglobin 11.6 g/dL, albumin 2.6 g/dL, and deficiencies of vitamin A, carotene, and zinc. Her serum folate was elevated and attributed to small intestinal bacterial overgrowth (SIBO). All celiac serologies were negative (deaminated gliadin, endomysial antibodies, and tissue-transglutaminase antibodies). HLA genotyping was permissive for celiac disease. Fecal alpha-2 antitrypsin was elevated. Duodenal aspirate showed >100,000 colony-forming units of gram-negative bacteria. CT enterography showed diffuse small bowel dilation with surrounding mesenteric adenopathy, biliary dilatation without evidence of obstruction, diffuse edema in the subcutaneous fat, and a right pleural effusion. Esophagogastroduodenoscopy revealed a normal duodenum until the second portion, where the normal villous pattern transitioned to a classic sprue-like appearance with a mosaic feature to the mucosa, scalloping of the folds, reduced height of the circular folds, and prominence of the submucosal vasculature.

The patient was treated with 10 days of tetracycline for possible SIBO. Her diarrhea had slight improvement and repeat biopsies demonstrated a persistent malabsorptive pattern at 1- and 2.5-year follow-up exams. A developing awareness of olmesartan sprue-like enteropathy led the patient's provider to advise stopping valsartan. Following cessation, gastrointestinal symptoms resolved within a period of several weeks. She underwent gluten challenge without symptom recurrence. Repeat duodenal biopsy 1 year following medication cessation demonstrated normalization of her villous architecture (Figure 3). Follow-up laboratory studies showed correction of anemia, transaminase elevations, and macro- and micronutrient deficiencies.

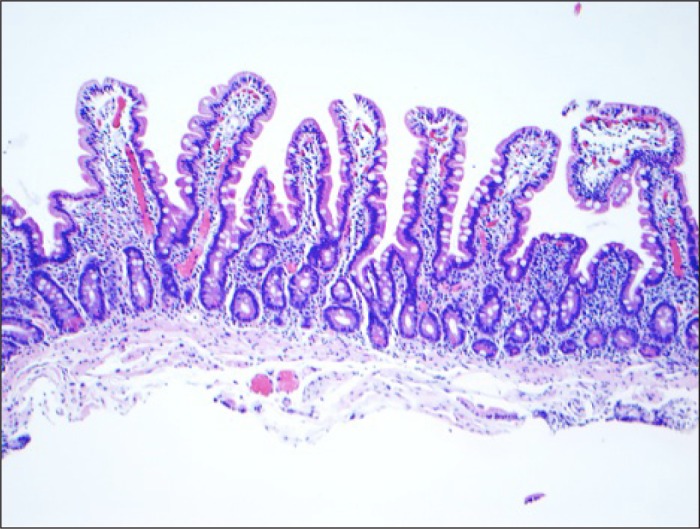

Figure 3.

Normal duodenal mucosa on biopsy 1 year following cessation of valsartan while consuming gluten-containing diet.

Discussion

ARBs other than olmesartan have rarely been implicated in sprue-like enteropathy.11 Understanding whether this is a class effect or a drug-specific effect is critical for further investigation of its mechanism. This patient had modest improvement from treatment with antibiotics for SIBO. Patients with olmesartan sprue-like enteropathy were also observed to have SIBO, but symptoms were not completely responsive to antibiotics. SIBO has also commonly been reported in patients with untreated celiac disease.12 The timing of her improvement, promptly after stopping valsartan and several months after treatment of SIBO, makes drug effect the more likely etiology.

Our case may represent a turning point in looking to a broader intestinal effect shared among ARBs.11 Current understanding of the mechanism of this drug effect remains in question, but there is suspicion that cell-mediated immunity plays a role, which is now supported by the observation of increased CD8+ T cells in duodenal biopsies from patients with olmesartan enteropathy.13

It is critical to keep all ARB medications in mind when evaluating patients with unexplained enteropathy until more is known about this severe reaction. We propose that if a patient with enteropathy is non-responsive to more conventional treatments, a trial off of ARB medication should be considered to ensure their clinical syndrome is not a rare drug side effect. Understanding this potential adverse drug reaction may help clarify the mechanism of olmesartan sprue-like enteropathy and may be helpful to clinicians in identifying cases of ARB-associated gastrointestinal illness.

Disclosures

Author contributions: ML Herman and A. Rubio-Tapia wrote the manuscript. ML Herman is the article guarantor. TT Wu was responsible for the pathology. JA Murray edited the manuscript.

Financial disclosure: None to report.

Informed consent was obtained for this case report.

Previous Presentation: This case report was presented as a poster at the ACG Annual Scientific Meeting; October 11-13, 2013; San Diego, California.

References

- 1.James PA, Oparil S, Carter BL, et al. 2014 Evidence-based guideline for the management of high blood pressure in adults: Report from the panel members appointed to the Eighth Joint National Committee (JNC 8). JAMA. 2014;311(5):507–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rubio-Tapia A, Herman ML, Ludvigsson JF, et al. Severe spruelike enteropathy associated with olmesartan. Mayo Clin Proc. 2012;87(8):732–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dreifuss SE, Tomizawa Y, Farber NJ, et al. Spruelike enteropathy associated with olmesartan: An unusual case of severe diarrhea. Case Rep Gastrointest Med. 2013;2013: 618071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.DeGaetani M, Tennyson CA, Lebwohl B, et al. Villous atrophy and negative celiac serology: A diagnostic and therapeutic dilemma. Am J Gastroenterol. 2013;108(5):647–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Agudo Fernández S.Sprue-like enteropathy due to olmesartan: A case report. Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014: S0210-5705(14)00164-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Abdelghany M, Gonzalez L, Slater J, Begley C. Olmesartan associated sprue-like enteropathy and colon perforation. Case Rep Gastrointest Med. 2014;2014: 494098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sanford ML, Nagel AK. A review of current evidence of olmesartan medoxomil mimicking symptoms of celiac disease. J Pharm Pract. Epub ahead of print March 28, 2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nielsen JA, Steephen A, Lewin M. Angiotensin-II inhibitor (olmesartan)-induced collagenous sprue with resolution following discontinuation of drug. World J Gastroenterol. 2013;19(40):6928–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Marthey L, Cadiot G, Seksik P, et al. Olmesartan-associated enteropathy: Results of a national survey. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2014;40(9):1103–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Flesch G, Müller P, Lloyd P. Absolute bioavailability and pharmacokinetics of valsartan, an angiotensin II receptor antagonist, in man. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 1997;52(2):115–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lebwohl B, Ludvigsson JF. Editorial: Sprue-like enteropathy due to olmesartan and other angiotensin receptor blockers–the plot thickens. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2014;40(10):1245–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rubio-Tapia A, Barton SH, Rosenblatt JE, Murray JA. Prevalence of small intestine bacterial overgrowth diagnosed by quantitative culture of intestinal aspirate in celiac disease. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2009;43(2):157–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rubio-Tapia A.Sprue-like enteropathy associated with olmesartan: Broadening the differential diagnosis of enteropathy. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2014;40(11-12):1362–1363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]