Abstract

Cytomegalovirus (CMV) infection is often seen in immunocompromised patients. Rarely, immunocompetent patients may present with CMV as a self-limiting, flu-like illness, though a few cases of significant organ-specific complications have been reported in these patients. We report a case in which a previously healthy man presented with hematochezia and an obstructing rectal mass thought to be rectal adenocarcinoma. Biopsy was positive for CMV, which was treated with full resolution of rectal mass confirmed with colonoscopy and barium contrast enema. This is the first reported case of CMV colitis mimicking rectal adenocarcinoma in an immunocompetent patient.

Introduction

Cytomegalovirus (CMV) is known to affect multiple organ systems and cause significant morbidity and mortality in immunocompromised patients. Generally, CMV infection in an immunocompetent host is asymptomatic or manifests as self-limiting, flu-like illness. Though immunocompetent hosts can be subclinical carriers of the virus, they rarely suffer from severe CMV-related disease burden.1

Case Report

A 42-year-old white man presented with a 3-month history of chronic small volume non-bloody diarrhea 4–5 times daily, associated with a 13.6-kg weight loss. He denied fever, recent antibiotic usage, arthralgias, rash, and use of nicotine, alcohol, or any illicit drugs. He denied use of steroids, immune-suppressive medication, or herbal medications. He denied recent travel history, sick contacts, or family history of gastrointestinal (GI) cancer or immunological disease. On presentation, his vitals were stable and within normal limits. Physical exam revealed a cachectic male with hyperactive bowel sounds without any abdominal tenderness or organomegaly. Blood investigations showed normal white cell count (5400/μL) with normal differential, microcytic anemia with hemoglobin 10 g/dL, and hypoalbuminemia with otherwise normal liver enzymes. Stool analysis showed 4+ leukocytes, but Clostridium difficile toxin, stool ova/parasite, occult blood test, and cultures were negative.

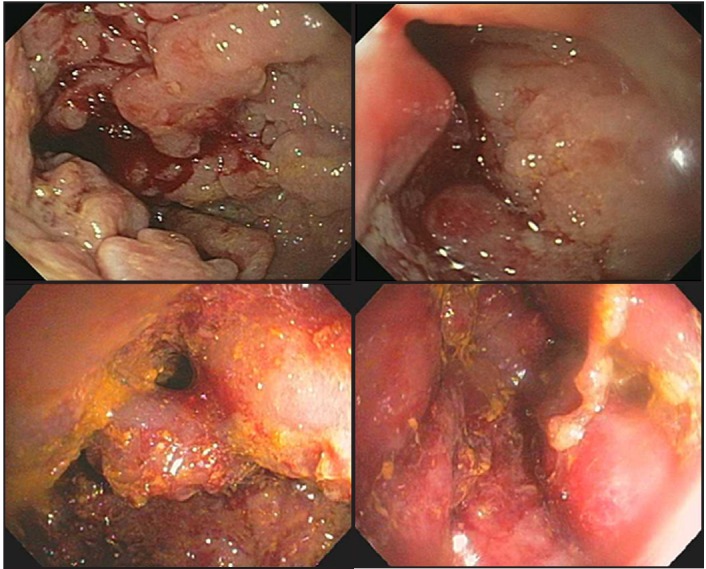

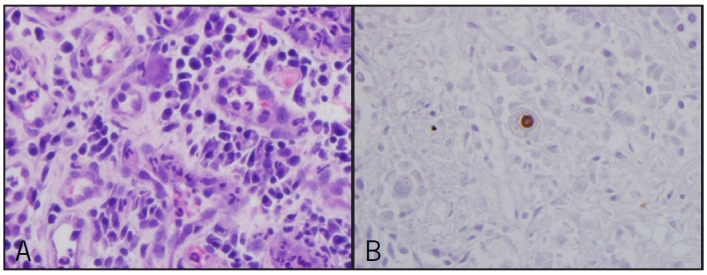

Upper endoscopy showed antral gastritis with biopsies positive for Helicobacter pylori, for which he was treated with standard triple therapy with documented eradication by negative stool antigen 4 weeks later. Colonoscopy showed a friable, fungating, ulcerated, near total obstructing mass in the proximal rectum 30 cm proximal to anus, through which neither colonoscope nor gastroscope could be passed (Figure 1). Biopsy of the mass revealed colonic mucosa with intense inflammation, granulation tissue, and positive staining for CMV inclusion bodies without evidence of malignancy (Figure 2). Abdominal CT was unremarkable. HIV testing was negative, CD4 count was 452, and CD4:CD8 ratio was 2.2.

Figure 1.

Colonoscopic images showing a friable, pseudopolypoid mucosa with partially obstructing mass in the rectum.

Figure 2.

Biopsy of the mass showing (A) cytomegalovirus inclusions in HE stain and (B) immunohistochemical staining for CMV, showing positive cell with ‘owl's eye’ appearance.

The patient was started on intravenous ganciclovir for CMV colitis, and after symptomatic improvement, was transitioned to oral ganciclovir therapy. Three weeks into the therapy, air contrast barium enema followed by a complete colonoscopy with extensive biopsies demonstrated healing benign erythematous mucosa, disappearance of inclusion bodies, and no evidence of malignancy (Figure 3). The cecum was reached on repeat colonoscopy without any evidence of inflammation in the colon. The patient had significant improvement of diarrhea and nutritional status.

Figure 3.

Air contrast enema performed 3 weeks into treatment showing resolution of rectal obstruction.

Discussion

CMV can affect any part of gastrointestinal tract; colitis is the most common manifestation, and is most commonly described in patients with HIV, a history of organ transplant, use of systemic steroids, or those receiving chemotherapy. CMV serology is positive in two-thirds of healthy adults.2 Risk of CMV disease increases with age due to declining T-cell function.3 The majority of the identified cases of CMV colitis in immunocompetent cases were in critically ill intensive care unit patients. Fever, diarrhea, and abdominal pain are the most common presenting symptoms. Half of patients with diarrhea reported gross hematochezia, and another 20% had positive fecal occult blood tests.4 The symptoms of CMV colitis are very non-specific, so diagnosis can be easily missed, especially in the presence of other confounding factors. Our patient was relatively young and manifested only diarrhea as his presenting symptom.

CMV colitis was established in our patient only after finding inclusion bodies in otherwise non-neoplastic mucosa. The classical colonoscopic findings in CMV colitis include well-demarcated ulcers, ulceroinfiltrative changes, and pseudomembrane formation in almost 75% cases.5 Endoscopic appearance of an obstructing colonic mass, as in our patient, is extremely rare and only reported in few cases. The treatment guidelines of CMV colitis in immunocompetent cases are not well defined. According to a meta-analysis, patients older than 55 years with comorbidities such as diabetes and chronic kidney disease have higher morbidity from CMV colitis if left untreated; therefore, early treatment is recommended in this group.6 For patients without these risk factors, guidelines are not established. Our patient did not have any of these risk factors; however, given the chronicity and severity of disease on colonoscopy, we opted for treatment with IV ganciclovir, with resolution.

Disclosures

Author contributions: R. Shah wrote the manuscript and is the article guarantor. G. Vaidya and A. Kalakonda wrote the manuscript. D. Manocha edited the manuscript. S. Rawlins supervised the writing process.

Financial disclosure: None to report.

Informed consent was obtained for this case report.

References

- 1. Horwitz CA, Henle W, Henle G, et al. Clinical and laboratory evaluation of cytomegalovirus-induced mononucleosis in previously healthy individuals. Report of 82 cases. Medicine (Baltimore). 1986;65: 124–134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Kalil AC, Florescu DF.. Prevalence and mortality associated with cytomegalovirus infection in nonimmunosuppressed patients in the intensive care unit. Crit Care Med. 2009;37(8):2350–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Emery V. Cytomegalovirus and the aging population. Drugs Aging. 2001;18(12):927–933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Klauber E, Briski LE, Khatib R.. Cytomegalovirus colitis in the immunocompetent host: An overview. Scand J Infect Dis. 1998;30(6):559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Seo TH, Kim JH, Ko SY, et al. Cytomegalovirus colitis in immunocompetent patients: A clinical and endoscopic study. Hepatogastroenterology. 2012;59(119):2137–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Galiatsatos P, Shrier I, Lamoureux E, Szilagyi A.. Meta-analysis of outcome of cytomegalovirus colitis in immunocompetent hosts. Dig Dis Sci. 2005;50(4):609–616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]