Abstract

Rising seawater temperature associated with global climate change is a significant threat to coral health and is linked to increasing coral disease and pathogen-related bleaching events. We performed heat stress experiments with the coral Pocillopora damicornis, where temperature was increased to 31°C, consistent with the 2–3°C predicted increase in summer sea surface maxima. 16S rRNA amplicon sequencing revealed a large shift in the composition of the bacterial community at 31°C, with a notable increase in Vibrio, including known coral pathogens. To investigate the dynamics of the naturally occurring Vibrio community, we performed quantitative PCR targeting (i) the whole Vibrio community and (ii) the coral pathogen Vibrio coralliilyticus. At 31°C, Vibrio abundance increased by 2–3 orders of magnitude and V. coralliilyticus abundance increased by four orders of magnitude. Using a Vibrio-specific amplicon sequencing assay, we further demonstrated that the community composition shifted dramatically as a consequence of heat stress, with significant increases in the relative abundance of known coral pathogens. Our findings provide quantitative evidence that the abundance of potential coral pathogens increases within natural communities of coral-associated microbes as a consequence of rising seawater temperature and highlight the potential negative impacts of anthropogenic climate change on coral reef ecosystems.

Keywords: Vibrio, Vibrio coralliilyticus, Pocillopora damicornis, corals, heat stress, pathogen

Introduction

The health and function of coral reefs is profoundly influenced by microorganisms, which often form species-specific associations with corals (Rohwer et al., 2002; Rosenberg et al., 2007; Mouchka et al., 2010). These ecological relationships can be mutualistic, commensal or pathogenic (Rosenberg et al., 2007), and diseases caused by pathogenic microbes have been identified as a key threat to coral reefs globally (Bourne et al., 2009; Burge et al., 2014). Diseases including white syndrome – which causes bleaching and lysis (Kushmaro et al., 1996; Ben-Haim et al., 2003a; Rosenberg and Falkovitz, 2004), white band (Ritchie and Smith, 1998; Aronson and Precht, 2001), white plague (Thompson et al., 2001), white pox (Patterson et al., 2002), black band (Frias-Lopez et al., 2002; Sato et al., 2009), and yellow band (Cervino et al., 2008) have all been attributed to microorganisms and have led to mass mortalities and significant loss of coral cover (Bourne et al., 2009).

There is evidence that the occurrence and severity of coral disease outbreaks is increasing globally (Harvell et al., 2004; Bruno et al., 2007; Mydlarz et al., 2010), potentially due to environmental stressors associated with phenomena such as increases in seawater temperature (Mouchka et al., 2010; Ruiz-Morenol et al., 2012). Heat stress may compromise the health of corals, leading to enhanced susceptibility to disease (Hoegh-Guldberg, 1999; Hoegh-Guldberg and Hoegh-Guldberg, 2004; Jokiel and Brown, 2004), or increase the abundance and/or virulence of pathogens (Vega Thurber et al., 2009; Vezzulli et al., 2010; Kimes et al., 2011). Increases in seawater temperature have been shown to change the composition and functional capacity of coral-associated microbial communities, including shifts to an elevated state of virulence, and pathogenicity (Vega Thurber et al., 2009).

While diverse groups of microbes, including bacteria, fungi, and viruses have been implicated in several coral diseases, one bacterial genus in particular has become a recurrent feature within coral disease research. Vibrio are globally distributed marine Gammaproteobacteria (Pollock et al., 2010), which harbor a diverse virulence repertoire that enables them to be efficient and widespread pathogens of a wide range of marine species (Santos Ede et al., 2011), including shell-fish (Jeffries, 1982), fish (Austin et al., 2005), algae (Ben-Haim et al., 2003b), mammals (Kaper et al., 1995; Shapiro et al., 1998; Oliver, 2005), and corals (Ben-Haim et al., 2003b). White syndrome in Montipora corals is caused by V. owensii (Ushijima et al., 2012), white band disease II in Acropora cervicornis has been attributed to V. charchariae (synonym for V. harveyi; Gil-Agudelo et al., 2006; Sweet et al., 2014), and a consortium of Vibrio are responsible for yellow band disease (Cervino et al., 2008; Ushijima et al., 2012). Furthermore, V. shiloi and V. coralliilyticus are the causative agents of bleaching in the coral species Oculina patagonica (Kushmaro et al., 1996, 1997, 1998; Toren et al., 1998) and the cauliflower coral Pocillopora damicornis (Ben-Haim and Rosenberg, 2002; Ben-Haim et al., 2003b), respectively.

Laboratory experiments using cultured isolates of V. shiloi (Kushmaro et al., 1996, 1997) and V. coralliilyticus (Ben-Haim and Rosenberg, 2002; Ben-Haim et al., 2003b) have fulfilled Koch’s postulates, with each species proven to be the causative agent of coral bleaching. V. shiloi causes bleaching in O. patagonica by using chemotaxis toward the coral mucus, before adhering to the coral surface and penetrating the epidermis (Banin et al., 2001). After colonization of the coral, cell multiplication occurs followed by production of the Toxin P molecule, which inhibits photosynthesis in the symbiotic zooxanthellae, resulting in coral bleaching, and tissue loss (Rosenberg and Falkovitz, 2004). Similarly, V. coralliilyticus causes bleaching, lysis and tissue loss in the coral P. damicornis (Ben-Haim and Rosenberg, 2002; Ben-Haim et al., 2003b; Meron et al., 2009; Garren et al., 2014). The mechanism behind V. coralliilyticus infection also includes motility and chemotaxis (Ben-Haim and Rosenberg, 2002; Ben-Haim et al., 2003b) and involves the post-colonization production of a potent extracellular metalloproteinase, which causes coral tissue damage (Ben-Haim and Rosenberg, 2002; Ben-Haim et al., 2003b). Another key similarity in the infection and bleaching mechanisms of V. shiloi and V. coralliilyticus is an increased infection rate under elevated seawater temperatures (Toren et al., 1998; Ben-Haim and Rosenberg, 2002; Ben-Haim et al., 2003b).

Heat stress can enhance coral disease by increasing host susceptibility to infection by pathogens (Bourne et al., 2009; Mouchka et al., 2010) or altering the behavior and virulence of pathogenic bacteria (Kushmaro et al., 1998; Banin et al., 2001; Ben-Haim and Rosenberg, 2002; Ben-Haim et al., 2003a,b; Koren and Rosenberg, 2006; Bourne et al., 2008; Kimes et al., 2011; Santos Ede et al., 2011). Notably, V. shiloi can only be isolated from bleached corals during summer months (Kushmaro et al., 1998) and laboratory experiments have shown that this species causes bleaching at an accelerated rate above 29°C, yet has negligible effect at 16°C (Kushmaro et al., 1998). Similarly, tissue loss caused by V. coralliilyticus is most rapid at elevated temperatures between 27 and 29°C (Ben-Haim and Rosenberg, 2002; Ben-Haim et al., 2003b). Seawater temperatures above 27°C have also been shown to play a direct role in the up-regulation of several V. coralliilyticus virulence genes, including factors involved in host degradation, secretion, antimicrobial resistance, and motility (Kimes et al., 2011). Up-regulation of motility is particularly notable as both V. shiloi and V. coralliilyticus exhibit enhanced chemotactic capacity at elevated temperatures (Banin et al., 2001; Garren et al., 2014). Heat-stressed corals also increase the production and release of signaling compounds including dimethylsulfoniopropionate (DMSP) at elevated temperature, further enhancing the ability of pathogens to locate, and colonize heat-stressed corals (Garren et al., 2014).

To date, our understanding of coral-associated Vibrio dynamics under elevated seawater temperatures has been solely derived from laboratory-based experiments using cultured isolates (Kushmaro et al., 1998; Toren et al., 1998; Banin et al., 2001; Ben-Haim and Rosenberg, 2002; Ben-Haim et al., 2003b; Garren et al., 2014). However, there is currently little understanding of how native communities of Vibrio, occurring within diverse natural assemblages of bacteria, will respond to elevated seawater temperatures. Understanding the dynamics of Vibrio populations within this complex, but also more realistic, scenario is important because it is very probable that Vibrios living in co-habitation with other competing and interacting species, will display different dynamics to those displayed by cultured isolates under laboratory conditions. For instance, inter-species antagonistic interactions among bacteria can strongly influence the growth and proliferation of other Vibrio species (Long et al., 2005), and we may expect similar ecological complexities to also occur within the coral holobiont. Here, we examined changes in the Vibrio population within a natural, mixed community of bacteria associated with the coral species P. damicornis on Heron Island, the Great Barrier Reef, Australia, and demonstrate that heat stress increases the abundance and changes the composition of potentially pathogenic Vibrio populations associated with corals.

Materials and Methods

Heat Stress Experiment

Three separate colonies (denoted A, B, and C) of the coral species P. damicornis were collected from within the Heron Island lagoon, on the Great Barrier Reef, Australia (23°26′41′′S, 151°54′47′′E), and translocated to the Heron Island Research Station. Colonies were placed into flow-through aquaria, which circulated water pumped from the reef flat to the Heron Island Research Station. The colonies were fragmented into 48 nubbins using bone cutters and acclimated for 8 days across six flow-through experimental tanks. The placement of the nubbins from each colony within each tank and the position of the tanks were randomized. During the experiment, three tanks were maintained at the ambient seawater temperature (22°C) experienced on the reef flat (control), while the remaining three tanks were exposed to a heat stress treatment, which involved the incremental ramping of seawater temperature by 1.5°C each day for seven consecutive days using one 25W submersible aquarium heater (Aqua One, Ingleburn, NSW, Australia) per tank, until a final temperature of 31°C was reached. Water was circulated in the tanks using one 8W maxi 102 Powerhead pump (Aqua One, Ingleburn, NSW, Australia) per tank. This temperature increase is in line with the predicted 2–3°C increases above current summer average seawater temperature (Hoegh-Guldberg, 1999, 2004; Berkelmans et al., 2004; Hoegh-Guldberg et al., 2007) for Heron Island.

Coral nubbins were sampled using sterile forceps at the start of the experiment (t0) and after 7 days for both the control (tfinal Control) and heat stress treatments (tfinal Heat stress). The nubbins were immediately placed into 15 mL falcon tubes containing 3 mL of RNAlater (Ambion, Life Technologies, Australia; Vega Thurber et al., 2009), which was a sufficient volume to completely immerse the nubbins. The nubbins were subsequently stored at -80°C until processing.

Photosynthetic Health of Corals

Photosynthetic health of the corals was checked using a diving pulse amplitude modulated (PAM) fluorometer (Walz, Germany) in the tfinal Control and tfinal 31°Ctreatments. Corals were dark-adapted for 10 min before their minimum fluorescence in the dark (FO) was recorded. Maximum fluorescence (FM) was determined using a saturating pulse of light for 0.8 s. The corals were then illuminated under 616 μmol photon m-2 s-1 light for 5 min to test their ability to sustain photosynthetic function under light. Maximum Quantum Yield (FV/FM) was measured on dark-adapted samples and effective quantum yield Y(PSII), regulated non-photochemical quenching Y(NPQ), and non-regulated non-photochemical quenching Y(NO) were measured on light adapted samples. To compare the changes in the FV/FM, Y(PSII), Y(NPQ), and Y(NO) measurements in the t0, tfinal Control, and tfinal Heat Stress treatments, a 1-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used (treatment) to determine significant differences (P < 0.05) between these measurements. Prior to this, data was tested for normality using the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test and Levene’s test was used for homogeneity of variance.

Coral-Bacterial Cell Separation

Coral nubbins were thawed slowly on ice and removed from the RNA-later solution using sterile forceps and kimwipes to remove excess solution (Vega Thurber et al., 2009). Replicate nubbins from the same donor colony (A, B, or C) were pooled and placed into sterile 150 mL conical flasks containing 15 mL sterile-autoclaved calcium and magnesium free seawater plus 10 mM EDTA (CMFSWE). The surfaces of the nubbins were airbrushed using 80 psi with a sterile 1 mL barrier tip (fresh tip for each new nubbin) in the conical flasks using sterile forceps to hold the nubbin in place. For each sample, the 15 mL tissue slurry was then filtered through a sterile 100 μm cell strainer (BD 352360) into a sterile 50 mL plastic centrifuge tube to remove host cells. The <100 μm filtrate was then filtered through a 3 μm filter (Whatman) and sterile filter tower apparatus (Nalgene) using vacuum pressure to remove any host cells larger than 3 μm. The resultant <3 μm filtrate (∼15 mL) was centrifuged at 14462 ×g to pellet the microbes for 5 min. DNA was extracted from the cell pellet using the MO BIO Ultra Clean Microbial DNA Kit (Carlsbad, CA, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Genomic DNA concentrations were measured using a Qubit 2.0 fluorometer (Invitrogen).

16S rRNA Amplicon Sequencing and Analysis

The bacterial community composition in each nubbin was determined using the universal bacterial 16S rRNA gene primers 27F (5′-AGAGTTTGATCMTGGCTCAG-3′) and 1392R (5′-ACGGGCGGTGTGTRC-3′; resulting in a 1365bp product) and the HotStarTaq Plus Master Mix Kit (Qiagen, USA). A 30 cycle amplification process was employed, incorporating the following cycling conditions: 94°C for 3 min, followed by 28 cycles of 94°C for 30 s, 53°C for 40 s and 72°C for 1 min, after which a final elongation step at 72°C for 5 min was performed. In addition, the composition and diversity of the Vibrio community was assessed using the Vibrio specific 16S rRNA gene primers VF169 (5′-GGATAACYATTGGAAACGATG-3′; Yong et al., 2006) and Vib2_R (5′-GAAATTCTACCCCCCTACAG-3′; Thompson et al., 2004; Vezzulli et al., 2012), resulting in a 511 bp product. In this instance, MangomixTM (Bioline) Taq polymerase was used and the following cycling conditions were performed: an initial activation step at 95°C for 120 s, followed by 30 cycles of denaturation at 95°C for 15 s, annealing at 53°C for 30 s and extension at 72°C for 30 s, after which a final elongation step at 72°C for 10 min was performed. In both cases, PCR products were used to prepare DNA libraries with the Illumina TruSeq DNA library preparation protocol. Sequencing was performed, following an additional amplification step using the 27F-519R primer pair for the 16S rRNA amplicon sequences on an Illumina MiSeq (at Molecular Research LP; Shallowater, TX, USA) following the manufacturer’s guidelines.

16S rRNA gene sequences were analyzed using the QIIME pipeline (Caporaso et al., 2010; Kuczynski et al., 2011). De novo Operational Taxonomic Units (OTUs) were defined at 97% sequence identity using UCLUST (Edgar, 2010) and taxonomy was assigned to the Greengenes database (version 13_8; McDonald et al., 2012) using BLAST (Altschul et al., 1990). Chimeric sequences were detected using ChimeraSlayer (Haas et al., 2011) and filtered from the dataset. Sequences were then rarefied to the same depth to remove the effect of sampling effort upon analysis (Santos et al., 2014) and chao1 diversity estimates were calculated. ANOVA was used (treatment) to determine significant differences (P < 0.05) between the diversity estimates in each treatment. Prior to this, data was tested for normality using the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test and Levene’s test was used for homogeneity of variance. In cases where these assumptions were not met, log10 transformations were performed. The community composition for each of the treatments t0, tfinal Control, and tfinal Heat Stress was averaged across the three replicates within each treatment.

Multivariate statistical software (PRIMER v6) was used to measure the degree of similarity between the bacterial community composition in each treatment (Clarke and Gorley, 2006). Data was square-root-transformed and the Bray–Curtis similarity was calculated between samples. Similarity percentage (SIMPER) analysis (Clarke, 1993) was used to identify the sequences contributing most to the dissimilarity between the treatments.

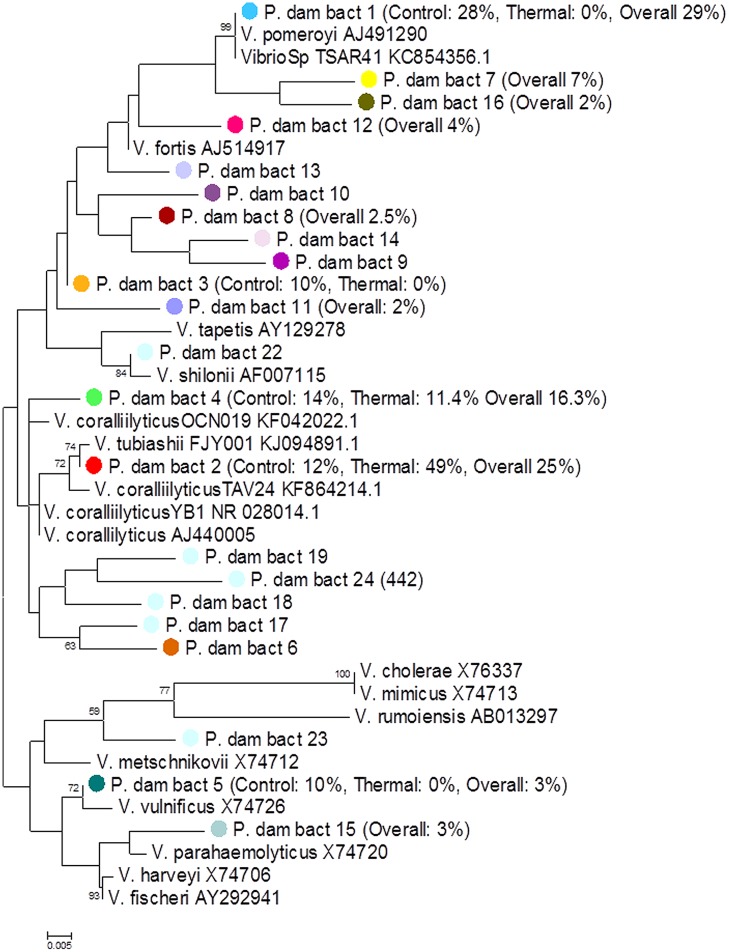

For the Vibrio-specific assay, the OTUs representing >1% of the total sequences were combined with various Vibrio species nucelotides taken from Yong et al. (2006) and V. coralliilyticus nucleotides taken from Huete-Stauffer et al. (unpublished), Ben-Haim et al. (2003b) and Ushijima et al. (2014) to build a phylogenetic tree. Sequences were first aligned and inspected using MUSCLE (Edgar, 2004) and the tree was constructed after 1,000 bootstrap re-samplings of the maximum-likelihood method using the Tamura-Nei model (Tamura et al., 2007) in MEGA 6.0 (Tamura et al., 2013), where only values >50% were displayed on the tree (Felsenstein, 1985). The OTU abundance was represented as a percentage of the overall community composition. OTUs were included on the tree if responsible for driving significant differences between the treatments according to SIMPER analysis and were color coded according to whether the OTU was more abundant in the tfinal Control treatment (blue circle) or the tfinal Heat stress treatment (red circle).

Quantitative PCR and Analysis

Quantitative PCR analyses targeting a Vibrio- specific region of the 16S rRNA gene and the heat shock protein gene (dnaJ) specific to V. coralliilyticus were conducted on all samples. Standards were created by growing the bacterial isolates V. parahaemolyticus (ATCC 17802) and V. coralliilyticus (ATCC BAA-450) overnight in Marine Broth (BD, Difco) at 37°C (150 rpm shaking water bath) and 28°C (170 rpm in a shaking incubator), respectively. Prior to qPCR analysis, calibration curves for each assay were created using viable counts from dilution series of the isolates. The cultures were homogenized and divided into 4 × 1 mL aliquots, washed three times with sterile phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and pelleted at 5200 g for 10 min. Three of the washed pellets were used for DNA extraction using the MO BIO Ultra Clean Microbial DNA Kit (Carlsbad, CA, USA), while the remaining washed pellet was resuspended in 1 mL PBS and 10-fold serial dilutions with Phosphate Buffered Saline were prepared in triplicate. Three replicate 100 μL aliquots from each dilution (10-5–10-8) were spread onto marine agar plates and grown at 37°C (V. parahaemolyticus) or 28°C (V. coralliilyticus) over 24–48 h, and resultant colonies were counted.

A 1:5 dilution of DNA: nuclease free water was used for all qPCR assays to reduce pipetting errors. The Vibrio population was assessed using 16S rRNA Vibrio primers Vib1_F (5′-GGCGTAAAGCGCATGCAGGT-3′) and Vib2_R (5′-GAAATTCTACCCCCCTACAG-3′; Thompson et al., 2004; Vezzulli et al., 2012) producing a 113 bp product. Power SYBR Select Master Mix (Applied Biosystems) was used, with reaction mixtures comprising 10 μL Master Mix, 5 μL of diluted (1:5) sample, and 0.4 μM of each primer to a final volume of 20 μL. The qPCR was performed using a Step One Plus (Applied Biosystems) and the following optimized cycling conditions: 2 min at 50°C, then an initial denaturation-hot start of 2 min at 95°C, followed by 40 cycles of the two-step reaction: 95°C for 15 s and 60°C for 1 min. This was followed by a holding stage at 72°C for 2 min and a melt curve stage.

The relative abundance of V. coralliilyticus was measured by targeting the dnaJ gene that encodes heat shock protein 40 in this species (Pollock et al., 2010), using the primers: Vc_dnaJ_F1 (5′-CGGTTCGYGGTGTTTCAAAA-3′) and Vc_dnaJ_R1 (5′-AACCTGACCATGACCGTGACA-3′) and a TaqMan probe, Vc_dna-J_TMP (5′-6-FAM-CAGTGGCGCGAAG-MGBNFQ-3′; 6-FAM; Pollock et al., 2010). Reaction mixtures included a 10 μL TaqMan Universal Master Mix II (Applied Biosystems), 5 μL of diluted (1:5) sample, 0.6 μM of each primer and 0.2 μM fluorophore-labeled TaqMan probe in a final total volume of 20 μL. The optimized qPCR cycling conditions were: 2 min at 50°C, then an initial denaturation-hot start of 10 min at 95°C, followed by 40 cycles of the following incubation pattern: 95°C for 15 s and 60°C for 1 min.

Resultant qPCR data for the Vibrio-specific and V. coralliilyticus assays were analyzed using Step One Software V2.3 (Applied Biosystems). The concentrations of bacteria were normalized to the coral surface area per cm2, which was calculated by paraffin wax dipping as described in Holmes (2008) and Veal et al. (2010). To compare the abundance of bacteria in the t0, tfinal Control, and tfinal Heat Stress treatments using the qPCR assays, ANOVA was used (treatment) to determine significant differences (P < 0.05) between the abundances in each treatment (qPCR). Prior to this, data was tested for normality using the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test and Levene’s test was used for homogeneity of variance. In cases where these assumptions were not met, log10 transformations were performed.

Results

Effects of Elevated Temperature on Coral Health

No visual signs of stress or bleaching were evident in the Control nubbins over the course of the experiment, yet evidence of bleaching was observed in the Heat Stress nubbins where significant levels of heat stress of the zooxanthellae were detected in the tfinal Heat Stress treatment compared to the tfinal Control nubbins using PAM fluorometry. Heat stressed corals showed a strong decline in zooxanthellae condition (significant decrease in the FV/FM (P = 0.002) and Y[PSII] (P = 0.003) measurements; Supplementary Information Tables S1 and S2), while simultaneously the zooxanthellae were protecting their cells from further photodamage by significantly increasing the xanthophyll cycle –Y[NPQ] measurements (Supplementary Information Tables S1 and S2).

Bacterial Community Composition

Differences in bacterial community composition between the tfinal Control and tfinal Heat Stressed corals were identified using 16S rRNA gene amplicon sequencing (Figure 1). The community composition of the tfinal Control and tfinal Heat Stress treatments were 42% dissimilar (SIMPER analysis; Supplementary Information Figure S1, Supplementary Information Table S3), while the largest difference (56%) in the community composition was between t0 and the tfinal Heat Stress treatments (Supplementary Information Table S4). Chao1 diversity estimates revealed that the tfinal Heat Stress treatment had significantly (P < 0.05) higher diversity (1406 ± 155 SD) compared to the tfinal Control (995 ± 23 SD).

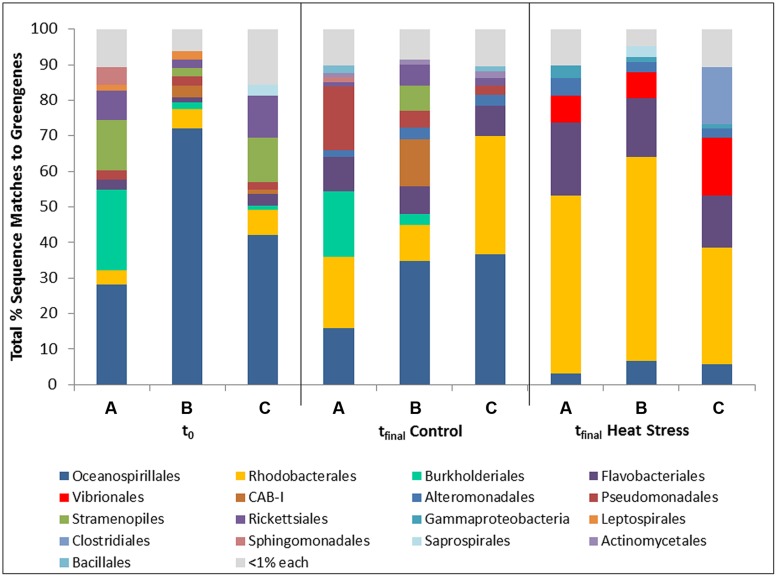

FIGURE 1.

Bacterial taxa (order) associated with the coral Pocillopora damicornis on Heron Island, the Great Barrier Reef at t0 (22°C; A–C are replicates), tfinal Control (22°C; A–C are replicates), and tfinal Heat stress (31°C; A–C are replicate nubbins) conditions using 16S rRNA gene amplicon sequencing. Hits were generated by comparing the sequences with BLASTn to the Greengenes database in QIIME.

The bacterial community at t0 was dominated by the Oceanospirillales (47%), which were primarily composed of members from the Endozoicomonacea, followed by Burkholderiales (8.5%), Rickettsiales (7%), and Rhodobacterales (6%) (Figure 1). A shift in the community was observed in control corals over the 7 day experiment involving an increase in the relative occurrence of sequences matching the Rhodobacterales (21%) and Flavobacteriales (8.6%), and a decrease in Oceanospirillales sequences (29%). These shifts are indicative of a mild experimental effect (Figure 1). However, a dramatic community shift was detected in the tfinal Heat Stress treatment relative to both the t0 and tfinal Control samples, which involved an increase in the relative proportion of Rhodobacterales (46.7%), Flavobacteriales (17.3%), and Vibrionales (10.5%). The occurrence of Vibrionales is notable because these organisms were not present in either control treatment (Figure 1). SIMPER analysis revealed that the decrease in Oceanospirillales abundance and increase in Vibrionales abundance were primarily responsible for differences in community composition between the tfinal Control and Heat Stress treatments (Supplementary Information Table S3).

Quantification of the General Vibrio Population and of V. coralliilyticus Using Real Time qPCR

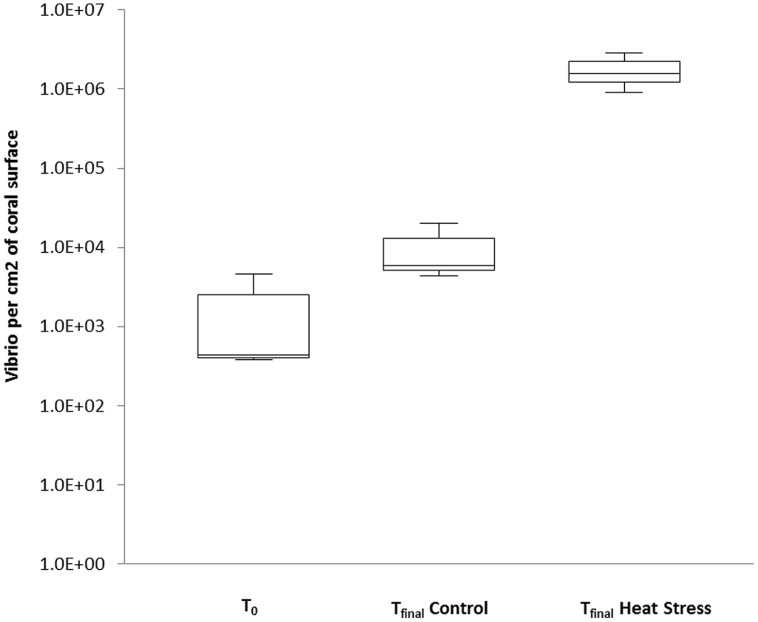

To confirm and quantify the increased abundance of Vibrio observed in tfinal Heat Stressed corals, we applied a qPCR assay to track changes in the relative abundance of the Vibrio community. The Vibrio community-specific qPCR assay detected Vibrios in all treatments (Figure 2, standard curve: R2 = 0.99, Efficiency % = 93.1), but abundances were significantly higher in the tfinal Heat Stress treatment, where they reached an average of 2.2 × 107 (±6.3 × 106 SD) cells cm-2 of coral surface (P < 0.01, Supplementary Information Table S5). Vibrio abundances in this treatment were two–three orders of magnitude higher than in the tfinal Control [1.4 × 105 (±9.5 × 104 SD) cells cm-2] and t0 (2.0 × 104 (±1.5 × 104 SD) cells cm-2) samples, respectively, (Figure 2).

FIGURE 2.

Quantitative PCR was performed to quantify the abundance of natural populations of Vibrios associated with the coral P. damicornis on Heron Island, the Great Barrier Reef at t0 (22°C), tfinal Control (22°C), and tfinal Heat stress (31°C) conditions. Standard curve: R2 = 0.99, Eff% = 93.1. Abundances are expressed as the number of bacteria per cm2. n = 3.

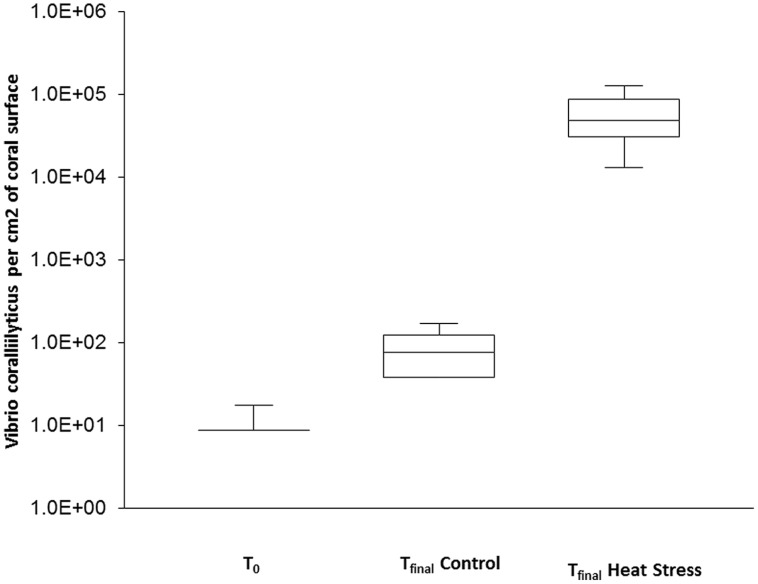

Variation in the abundance of the coral pathogen V. coralliilyticus was also assessed using qPCR. In the t0 corals, V. coralliilyticus was detected in only one of the three replicate colonies, in very low abundance (17.5 cells cm-2 of coral surface). Similarly, low concentrations were observed in the tfinal Control samples, with abundances in one replicate below the detection limit and a mean of 81.5 cells cm-2 observed in the other two replicates. In contrast, V. coralliilyticus concentrations in the tfinal Heat Stress treatment 6.3 × 104 (±3.4 × 104 SD) were significantly higher (P < 0.05, Supplementary Information Table S6) and reached up to four orders of magnitude higher than the tfinal Control (Figure 3).

FIGURE 3.

Quantitative PCR assays were used to quantify the abundance of natural populations of Vibrio coralliilyticus associated with the coral P. damicornis on Heron Island, the Great Barrier Reef at t0 (22°C), tfinal Control (22°C), and tfinal Heat stress (31°C) conditions, standard curve: R2 = 0.995, Eff% = 99.9. Abundances are expressed as the number of bacteria per cm2. n = 3.

Characterizing Changes in the Vibrio Population Induced by Heat Stress

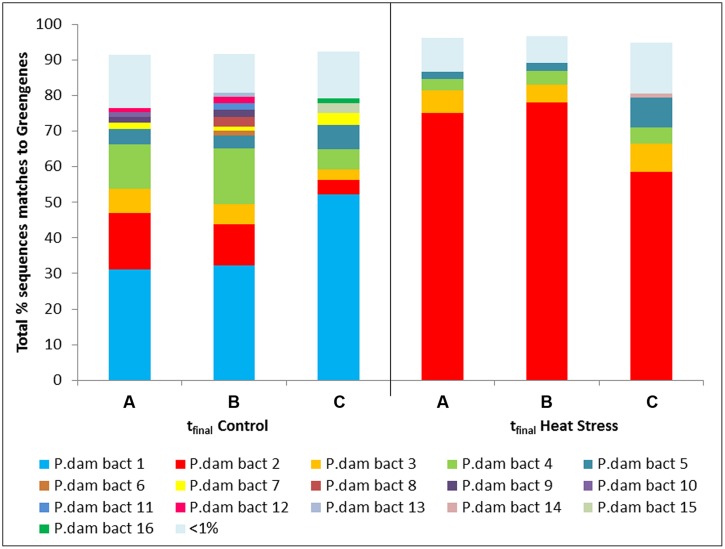

Using a Vibrio-specific 16S rRNA amplicon sequencing approach we observed a clear shift in the composition of the coral Vibrio community between the tfinal Control and tfinal Heat Stress treatments. Consistent with the results of the qPCR assay, where negligible numbers of Vibrio were detected, a small number (n = 2024) of Vibrio sequences were observed in the t0 treatment. To avoid rarefying to this very low number of sequences, the t0 treatment was subsequently omitted from the data set, as we consider the key comparison to test for the effects of increased seawater temperatures to be the tfinal Control vs. Heat Stress treatments. The Vibrio community composition was different between the tfinal Control and Heat Stress treatments. In particular, two OTUs, denoted P. dam bact 1 and bact 2, were responsible for driving the largest differences (29 and 25%, respectively, according to SIMPER analysis) between treatments (Figure 4, Supplementary Information Table S7). While the P. dam bact 1 OTU comprised an average of 38.5% (±6.8%) of the community in the tfinal control treatment (Figure 4), it was not present in the tfinal Heat Stress treatment. In contrast, the P. dam bact 2 OTU was more abundant in corals from the tfinal Heat Stress treatment, comprising an average of 70.6% (±6.0%) of the total Vibrio community (Figure 4), while representing only 10.4% (±3.4%) of the community in the tfinal control treatment. Phylogenetic analysis of the two dominant Vibrio OTUs (Figure 5) revealed that P. dam bact 1 appears to be closely related to V. pomeryoi (AJ491290), while P. dam bact 2 may be related to V. tubiashii (KJ094891.1) and V. coralliilyticus (KF864214.1; Figure 5).

FIGURE 4.

Operational taxonomic units (OTUs) from the Vibrio community associated with the coral P. damicornis on Heron Island, the Great Barrier Reef at tfinal Control (22°C; A–C are replicate nubbins) and tfinal Heat stress (31°C; A–C are replicate nubbins) conditions.

FIGURE 5.

Phylogenetic tree of the Vibrio community associated with the coral P. damicornis. The colors of OTU circles match the color of OTUs from Figure 4. The percentage abundances of the OTUs in the tfinal Control and tfinal Heat Stress treatments are represented as a percentage of the total community composition only if the OTU is responsible for driving significant differences between the treatments according to SIMPER analysis (Supplementary Table S6). The numbers at the nodes are percentages indicating the levels of bootstrap support, based on 1,000 resampled data sets where only bootstrap values of >50% are shown. The scale bar represents 0.005 substitutions per nucleotide position.

Discussion

Rising global temperatures, related to anthropogenically driven climate change, are expected to drive the geographical expansion of pathogens and the spread of disease outbreaks (Harvell et al., 1999, 2002; Burge et al., 2014). In marine habitats, a rise in Vibrio-induced diseases has been identified as an emerging global issue and has been correlated to rising seawater temperatures (Vezzulli et al., 2012; Baker-Austin et al., 2013). For instance, increasing seawater temperature has been linked to increased Vibrio occurrence in the North and Baltic Seas and a concurrent increase in cases of human infections by Vibrio species in this region (Vezzulli et al., 2012; Baker-Austin et al., 2013). Similarly, increasing numbers of human infections by V. vulnificus and V. parahaemolyticus off the coast of Spain have been linked to higher seawater temperatures (Martinez-Urtaza et al., 2010).

Clear links between elevated seawater temperature and the global decline of corals have also become increasingly apparent (Mydlarz et al., 2009; De’ath et al., 2012). Elevated seawater temperatures have led to (i) increased occurrence of coral bleaching, whereby symbiotic dinoflagellates are expelled from the coral host (Hoegh-Guldberg et al., 2007) and (ii) a situation where many corals are living close to their thermal physiological maximum (Hoegh-Guldberg et al., 2007). In addition to these direct effects on coral physiology and the coral-Symbiodinium symbiosis, rising seawater temperatures have also been linked to increased incidence of coral disease and microbial-associated bleaching, or white syndrome (Bruno et al., 2007). In particular, V. shiloi and V. coralliilyticus have been identified as temperature-dependent pathogens responsible for coral bleaching (Kushmaro et al., 1996, 1997, 1998; Ben-Haim and Rosenberg, 2002; Ben-Haim et al., 2003a).

To date, the majority of research investigating the roles of Vibrio sp. in coral disease has been conducted in the laboratory using cultured isolates obtained from healthy and diseased corals (Kushmaro et al., 1998; Banin et al., 2000; Ben-Haim and Rosenberg, 2002; Ben-Haim et al., 2003a; Koren and Rosenberg, 2006; Vidal-Dupiol et al., 2011; Garren et al., 2014; Rubio-Portillo et al., 2014) with relatively few studies assessing natural populations of coral-associated Vibrio during heat stress or bleaching events (Bourne et al., 2008; Vezzulli et al., 2010). Community finger-printing approaches have previously revealed increases in the relative abundance of Vibrio populations during a naturally occurring bleaching event on the GBR (Bourne et al., 2008), while the appearance of V. coralliilyticus in diseased specimens of the octocoral Paramuricea clavata was also linked to elevated seawater temperature (Vezzulli et al., 2010).

In our study, initial evidence for a temperature induced increase in coral-associated Vibrio was provided by 16S rRNA gene amplicon sequencing. Corals from the control treatments were dominated by the Oceanospirillales, primarily due to the abundance of Endozoicomonacea, a group widely shown to be associated with healthy colonies of diverse coral species (Morrow et al., 2012, 2014; Bayer et al., 2013; Neave et al., 2014) including P. damicornis (Bourne and Munn, 2005). In contrast, the bacterial community in tfinal Heat Stressed corals was characterized by significantly higher levels of diversity (Chao1) than the tfinal Control corals. This is consistent with previous studies where diversity increased among white plague affected corals (Sunagawa et al., 2009). The tfinal Heat Stressed corals contained diverse assemblages of copiotrophic and potentially opportunistic microbes including Rhodobacteriales, Flavobacteriales, and Vibrionales. Notably, while Vibrio sequences made up 10.5% of sequences in corals from the tfinal Heat Stress treatment, they were completely absent in the t0 and tfinal Control samples. In addition, a substantial decrease in Oceanospirillales and a disappearance of Burkholderiales was observed in tfinal Heat Stressed corals. The changes observed here are consistent with previous research indicating that specific bacterial populations, including putative pathogens, emerge, and dominate the coral-associated bacterial community during environmental stress events (Roder et al., 2014). These community shifts may be a direct effect of temperature on the growth of specific members of the microbial community, or alternatively caused by a change in the chemicals released by heat-stressed corals (Garren et al., 2014).

Due to the increased proportion of Vibrio sequences in the 16S rRNA amplicon analysis and the potential role of Vibrio in coral disease (Vezzulli et al., 2010), we investigated the dynamics of this community further using targeted qPCR and Vibrio-specific amplicon sequencing approaches. A clear shift in the composition of the Vibrio community was observed in conjunction with the increased Vibrio abundance under elevated seawater temperature. Using qPCR, we detected low abundances of total Vibrio in the t0 and tfinal Control treatments, consistent with previous observations in healthy corals (Ritchie and Smith, 2004; Raina et al., 2009; Vezzulli et al., 2013) and our 16S rRNA amplicon sequencing results. However, we observed an increase in relative Vibrio abundance of two–three orders of magnitude in the tfinal Heat Stressed corals. These patterns support previous reports that Vibrio abundance is linked to seawater temperature (Rubio-Portillo et al., 2014). While the increased abundance of V. coralliilyticus is part of a broader increase in abundance of total Vibrios, the magnitude of increase was substantially higher in V. coralliilyticus (four orders of magnitude compared to 2–3 orders of magnitude). This indicates that the putative coral pathogen V. coralliilyticus particularly benefited from the increased seawater temperature during in this study.

The ecological role of the resident Vibrio community in the health of corals is likely to vary substantially across species. Some Vibrios appear to form mutualistic relationships with corals by fixing nitrogen in the mucus (Chimetto et al., 2008) whereas others are putative agents of coral disease. However, despite substantial evidence of links between coral disease and Vibrio occurrence, in many cases it is unknown whether these organisms are the primary etiological agents or simply opportunistic colonizers that exploit the coral when host health is compromised (Bourne et al., 2008; Raina et al., 2010). While difficulties in assigning Vibrio taxonomy using 16S rRNA sequencing approaches are sometimes encountered (Cana-Gomez et al., 2011), our Vibrio specific 16S amplicon assay demonstrated clear differences between the Vibrio communities in the control and heat-stress samples and identified two key OTUs responsible for driving these differences. In the control corals the Vibrio community was dominated by OTUs that matched V. pomeroyi (AJ491290), supporting previous research showing V. pomeryoi is found year round in healthy corals (Rubio-Portillo et al., 2014). V. pomeryoi is not known to be involved in coral disease and is likely a normal resident member of the coral-associated community (Rubio-Portillo et al., 2014). Up to 70% of the Vibrio community in tfinal Heat Stressed corals was comprized of a single OTU (OTU P. dam bact 2), which our phylogenetic analysis indicates is closely related to the oyster pathogen V. tubiashii (KJ094891.1; Hada et al., 1984; Hasegawa et al., 2008; Richards et al., 2015) and the coral pathogen V. coralliilyticus (KF864214.1). V. tubiashii and V. coralliilyticus are highly related species (Ben-Haim et al., 2003b), and whilst the taxonomy of OTU P. dam bact 2 remains to be fully resolved, the phylogenetic positioning close to several V. coralliilyticus strains indicates that this organism may be V. coralliilyticus. This would be consistent with the findings of our V. coralliilyticus qPCR analysis, where a four orders of magnitude increase in abundance of V. coralliilyticus was observed in corals from the tfinal Heat Stress treatment. These results are consistent with findings of Vezzulli et al. (2010) who only observed V. coralliilyticus in diseased coral specimens, as well as Ben-Haim and Rosenberg (2002) who, using cultured isolates of V. coralliilyticus, demonstrated that elevated temperatures are crucial to the infection of P. damicornis.

Our findings demonstrate, for the first time, that elevated seawater temperature increases the abundance and alters the composition of an environmental Vibrio community occurring among a mixed natural microbial community associated with the ecologically important coral species P. damicornis. Importantly, these microbial shifts involve a dramatic rise in the relative abundance of pathogens including V. coralliilyticus. Our research builds upon previous studies using cultured isolates, to highlight that natural populations of Vibrios, occurring within mixed natural communities of coral associated microbes may rise to prominence under heat stress conditions. Currently, up to a third of all coral species face extinction (Carpenter et al., 2008), with coral disease recognized as a significant and increasing threat. Our data provide direct quantitative support for the theory that increasing sea surface temperature occurring as a result of climate change, will affect coral reefs by promoting an increase in the abundance of coral pathogens.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

This research was funded by an Australian Research Council Grant (DP110103091) to JS and RS, a Human Frontiers in Science Program Award (no. RGY0089) to RS and JS, the Australian Coral Reef Society Terry Walker Prize 2012 to JT, and a post-graduate award to JT from the Department of Environmental Science and Climate Change Cluster at the University of Technology Sydney. JS and NW were funded through Australian Research Council Future Fellowships FT130100218 and FT120100480, respectively. We are grateful to the Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority for coral collection permits G09/31733.1 (PJ Ralph, University of Technology Sydney).

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: http://journal.frontiersin.org/article/10.3389/fmicb.2015.00432/abstract

References

- Altschul S. F., Gish W., Miller W., Myers E. W., Lipman D. J. (1990). Basic local alignment search tool. J. Mol. Biol. 215 403–410 10.1016/S0022-2836(05)80360-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aronson R. B., Precht W. F. (2001). White-band disease and the changing face of Caribbean coral reefs. Hydobiologica 460 25–38 10.1023/A:1013103928980 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Austin B., Austin D., Sutherland R., Thompson F., Swings J. (2005). Pathogenicity of vibrios to rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss, Walbaum) and Artemia nauplii. Environ. Microbiol. 7 1488–1495 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2005.00847.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker-Austin C., Trinanes J. A., Taylor G. H., Hartnell R., Siitonen A., Martinez-Urtaza J. (2013). Emerging Vibrio risk at high latitudes in response to ocean warming. Nat. Clim. Chang. 3 73–77. [Google Scholar]

- Banin E., Ben-Haim Y., Israely T., Loya Y., Rosenberg E. (2000). Eject of the environment on the bacterial bleaching of corals. Water Air Soil Pollut. 123 337–352 10.1023/A:1005274331988 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Banin E., Israely T., Fine M., Loya Y., Rosenberg E. (2001). Role of endosymbiotic zooxanthellae and coral mucus in the adhesion of the coral-bleaching pathogen Vibrio shiloi to its host. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 199 33–37 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2001.tb10647.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bayer T., Neave M. J., Alsheikh-Hussain A., Aranda M., Yum L. K., Mincer T., et al. (2013). The microbiome of the red sea coral Stylophora pistillata is dominated by tissue-associated Endozoicomonas bacteria. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 79 47–89 10.1128/AEM.00695-13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ben-Haim Y., Rosenberg E. (2002). A novel Vibrio sp. pathogen of the coral Pocillopora damicronis. Mar. Biol. 141 47–55 10.1007/s00227-002-0797-6 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ben-Haim Y., Zicherman-Keren M., Rosenberg E. (2003a). Temperature regulated bleaching and lysis of the coral Pocillopora damicronis by the novel pathogen Vibrio coralliilyticus. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 69 4236–4242 10.1128/AEM.69.7.4236-4242.2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ben-Haim Y., Thompson F. L., Thompson C. C., Cnockaert M. C., Hoste B., Swings J., et al. (2003b). Vibrio coralliilyticus sp. Nov., a temperature-dependent pathogen of the coral Pocillopora damicornis. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 53 309–315 10.1099/ijs.0.02402-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berkelmans R., De’ath G., Kininmonth S., Skirving W. J. (2004). A comparison of the 1998 and 2002 coral bleaching events on the Great Barrier Reef: spatial correlation, patterns and predictions. Coral Reefs 23 74–83 10.1007/s00338-003-0353-y [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bourne D. G., Garren M., Work T. M., Rosenberg E., Smith G. W., Harvell C. D. (2009). Microbial disease and the coral holobiont. Trends Microbiol. 17 554–562 10.1016/j.tim.2009.09.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bourne D. G., Iida Y., Uthicke S., Smith-Keune C. (2008). Changes in coral-associated microbial communities during a bleaching event. ISME J. 2 350–363 10.1038/ismej.2007.112 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bourne D. G., Munn C. B. (2005). Diversity of bacteria associated with the coral Pocillopora damicornis from the Great Barrier Reef. Environ. Microbiol. 7 1162–1174 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2005.00793.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruno J. F., Selig E. R., Casey K. S., Page C. A., Willis B. L. (2007). Thermal stress and coral cover as drivers of coral disease outbreaks. PLoS Biol. 5:e124 10.1371/journal.pbio.0050124 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burge C. A., Eakin C. M., Friedman C. S., Froelich B., Hershberger P. K., Hofmann E. E., et al. (2014). Climate change influences on marine infectious diseases: implications for management and society. Annu. Rev. Mar. Sci. 6 249–277 10.1146/annurev-marine-010213-135029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cana-Gomez A., Hoj L., Owens L., Andreakis N. (2011). Multilocus sequence analysis provides basis for fast and reliable identification of Vibrio harveyi-related species and reveals previous misidentification of important marine pathogens. Syst. Appl. Microbiol. 34 561–565 10.1016/j.syapm.2011.09.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caporaso J. G., Kuczynski J., Stombaugh J., Bittinger K., Bushman F. D., Costello E. K., et al. (2010). QIIME allows analysis of high-throughput community sequencing data. Nat. Methods 7 335–336 10.1038/nmeth.f.303 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carpenter K. E., Abrar M., Aeby G., Aronson R. B., Banks S., Bruckner A., et al. (2008). One-third of reef-building corals face elevated extinction risk from climate change and local impacts. Science 321 560–563 10.1126/science.1159196 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cervino J. M., Thompson F. L., Gomez-Gil B., Lorence E. A., Goreau T. J., Hayes R. L., et al. (2008). The Vibrio core group induces yellow band disease in Caribbean and Indo-pacific reef-builing corals. J. Appl. Microbiol. 105 1658–1671 10.1111/j.1365-2672.2008.03871.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chimetto L. A., Brocchi M., Thompson C. C., Martins R. C. R., Ramos H. R., Thompson F. L. (2008). Vibrios dominate as culturable nitrogen-fixing bacteria of the Brazilian coral Mussismilia hispida. Syst. Appl. Microbiol. 31 312–319 10.1016/j.syapm.2008.06.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clarke K. R. (1993). Non-parametric multivariate analyses of changes in community structure. Aust. J. Ecol. 18 117–143 10.1111/j.1442-9993.1993.tb00438.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Clarke K. R., Gorley R. N. (2006). PRIMER v6: User Manual/Tutorial PRIMER-E. Plymouth: Plymouth Marine Laboratory. [Google Scholar]

- De’ath G., Fabricius K., Sweatman H., Puotinen M. (2012). The 27-year decline of coral cover on the great barrier reef and its causes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 109 17995–17999 10.1073/pnas.1208909109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edgar R. C. (2010). Search and clustering orders of magnitude faster than BLAST. Bioninformatics 26 2460–2461 10.1093/bioinformatics/btq461 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edgar R. C. (2004). MUSCLE: multiple sequence alignment with high accuracy and high throughput. Nucleic Acids Res. 32 1792–1797 10.1093/nar/gkh340 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Felsenstein J. (1985). Confidence limits on phylogenies: an approach using the bootstrap. Evolution 39 783–791 10.2307/2408678 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frias-Lopez J., Zerkl A. L., Bonheyo G. T., Fouke B. W. (2002). Partitioning of bacterial communities between seawater and healthy, black band diseased and dead coral surfaces. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 68 2214–2228 10.1128/AEM.68.5.2214-2228.2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garren M., Son K., Raina J. B., Rusconi R., Menolascina F., Shapiro O. H., et al. (2014). A bacterial pathogen uses dimethylsulfoniopropionate as a cue to target heat-stressed corals. ISME J. 8 999–1007 10.1038/ismej.2013.210 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gil-Agudelo D. L., Smith G. W., Weil E. (2006). The white band disease type II pathogen in Puerto Rico. Rev. Biol. Trop. 54(Suppl. 3), 59–67.18457175 [Google Scholar]

- Haas B. J., Gevers D., Earl A. M., Felgarden M., Ward D. V., Giannoukos G., et al. (2011). Chimeric 16S rRNA sequence formation and detection in Sanger and 454-pyrosequenced PCR amplicons. Genome Res. 21 494–504 10.1101/gr.112730.110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hada H. S., West P. A., Lee J. V., Stemmler J., Colwell R. R. (1984). Vibrio tubiashii sp. Nov., a pathogen of bivalve mollusks. Int. J. Sys. Bacteriol. 34 1–4 10.1099/00207713-34-1-1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Harvell C. D. R., Aronson N., Baron J., Connell A., Dobson S., Ellner L., et al. (2004). The rising tide of ocean diseases: unsolved problems and research priorities. Front. Ecol. 2:375–382 10.1890/1540-9295(2004)002[0375:TRTOOD]2.0.CO;2 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Harvell C. D., Kim K., Burkholder J. M., Colwell R. R., Epstein P. R., Grimes D. J., et al. (1999). Emerging marine diseases: climate links and anthropogenic factors. Science 285 1505–1510 10.1126/science.285.5433.1505 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harvell C. D., Mitchell C. E., Ward J. R., Altizer S., Dobson A. P., Ostfeld R. S., et al. (2002). Climate warming and disease risks for terrestrial and marine biota. Science 296 2158–2162 10.1126/science.1063699 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasegawa H., Lind E. J., Boin M. A., Hase C. C. (2008). The extracellular metalloprotease of Vibrio tubiashii is a major virulence factor for pacific oyster (Crassostrea gigas) larvae. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 74 4101–4110 10.1128/AEM.00061-08 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoegh-Guldberg H., Hoegh-Guldberg O. (2004). Biological, Economic and Social Impacts of Climate Change on the Great Barrier Reef. Sydney: World Wide Fund for Nature [Google Scholar]

- Hoegh-Guldberg O. (1999). Climate change, coral bleaching and the future of the world’s coral reefs. Mar. Freshw. Res. 50 839–866 10.1071/MF99078 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hoegh-Guldberg O. (2004). Coral reefs in a century of rapid environmental change. Symbiosis 37 1–31. [Google Scholar]

- Hoegh-Guldberg O., Anthony K., Berkelmans R., Dove S., Fabricus K., Lough J., et al. (2007). “Chapter 10. Vulnerability of reef-building corals on the Great Barrier Reef to climate change,” in Climate Change and the Great Barrier Reefs, eds Johnson J. E., Marshall P. A. (Townsville, QLD: Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority and Australian Greenhouse Office; ). [Google Scholar]

- Holmes G. (2008). Estimating three-dimensional surface areas on corals. J. Exp. Mar. Biol. Ecol. 365 67–73 10.1016/j.jembe.2008.07.045 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jeffries V. E. (1982). Three V-i7brio strains pathogenic to larvae of Crassostrea virginica and Ostrea edulis. Aquaculture 29 201–226 10.1016/0044-8486(82)90136-3 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jokiel P. L., Brown E. K. (2004). Global warming, regional trends and inshore environmental conditions influence coral bleaching in Hawaii. Glob. Change Biol. 10 1627–1641 10.1111/j.1365-2486.2004.00836.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kaper J. B., Morris J. G., Levine M. M. (1995). Cholera. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 8 48–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimes N. E., Grim C. J., Johnson W. R., Hasan N. A., Tall B. D., Kothary M. H., et al. (2011). Temperature regulation of virulence factors in the pathogen Vibrio coralliilyticus. ISME J. 6 835–846 10.1038/ismej.2011.154 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koren O., Rosenberg E. (2006). Bacteria associated with mucus and tissues of the coral Oculina patagonica in summer and winter. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 728 5254–5259 10.1128/AEM.00554-06 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuczynski J., Stombaugh J., Walters W. A., Gonzalex A., Caporaso J. G., Knight R. (2011). Using QIIME to analyse 16S Rrna gene sequences from microbial communities. Curr. Protoc. Bioinformatics Chap. 10 Unit 10.7. 10.1002/0471250953.bi1007s36 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kushmaro A., Loya Y., Fine M., Rosenberg E. (1996). Bacterial infection and coral bleaching. Nature 380:396 10.1038/380396a0 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kushmaro A., Rosengerg E., Fine M., Ben Haim Y., Loya Y. (1998). Effect of temperature on bleaching of the coral Oculina patagonica by Vibrio AK-1. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 171 131–137 10.3354/meps171131 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kushmaro A., Rosenberg E., Fine M., Loya Y. (1997). Bleaching of the coral Oculina patagonica by Vibrio AK-1. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 147 159–165 10.3354/meps147159 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Long R. A., Rowley D. C., Zamora R., Liu J., Bartlett D. H., Azam F. (2005). Antagonistic interactions among marine bacteria impede the proliferation of Vibrio cholerae. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 71 8531–8536 10.1128/AEM.71.12.8531-8536.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez-Urtaza J., Bowers J. C., Trinanes J., DePaola A. (2010). Climate anomalies and the increasing risk of Vibrio parahaemolyticus and Vibrio vulnificus illnesses. Food Res. Int. 43 1780–1790 10.1016/j.foodres.2010.04.001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McDonald D., Price M. N., Goodrich J., Nawrocki E. P., DeSantis T. Z., Probst A., et al. (2012). An improved Greengenes taxonomy with explicit ranks for ecological and evolutionary analyses of bacteria and archaea. ISME J. 6 610–618 10.1038/ismej.2011.139 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meron D., Efrony R., Johnson W. R., Schaefer A. L., Morris P. J., Rosenberg E., et al. (2009). Role of flagellar in virulence of the coral pathogen Vibrio coralliilyticus. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 75 5704–5707 10.1128/AEM.00198-09 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morrow K., Bourne D. G., Humphrey C., Botté E., Laffy P., Zanefeld J., et al. (2014). Natural volcanic CO2 seeps reveal future trajectories for host-microbial associations in corals and sponges. ISME J. 9 894–908 10.1038/ismej.2014.188 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morrow K., Moss A. G., Chadwick N. E., Liles M. R. (2012). Bacterial associates of two caribbean coral species reveal species-specific distribution and geographic variability. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 78 6438 10.1128/AEM.01162-112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mouchka M. E., Hewson I., Harvell C. D. (2010). Coral-associated bacterial assemblages: current knowledge and the potential for climate-driven impacts’ integr Comp. Biol. 50 662–674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mydlarz L. D., Couch C. S., Weil E., Smith G., Harvell C. D. (2009). Immune defenses of healthy, bleached and diseased Montastraea faveolata during a natural bleaching event. Dis. Aquat. Org. 87 67–78 10.3354/dao02088 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mydlarz L. D., McGinty E. S., Harvel C. D. (2010). What are the physiological and immunological responses of coral to climate warming and disease? J. Exp. Biol. 213 934–945 10.1242/jeb.037580 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neave M. J., Michell C. T., Apprill A., Voolstra C. R. (2014). Whole-genome sequences of three symbiotic Endozoicomonas bacteria. Genome Accounc. 2: e00802-14 10.1128/genomeA.00802-14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oliver J. D. (2005). Wound infections caused by Vibrio vulnificus and other marine bacteria. Epidemiol. Infect. 133 383–391 10.1017/S0950268805003894 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patterson K. L., Porter J. W., Ritchie K. B., Polson S. W., Mueller E., Peters E. C., et al. (2002). The etiology of white pox, a lethal disease of the Carbbean elkhorn coral, Acropora palmata. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 99 8725–8730 10.1073/pnas.092260099 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pollock F. J., Morris P. J., Willis B. L., Bourne D. G. (2010). Detection and quantification of the coral pathogen Vibrio coralliilyticus by real-time with taqman fluorescent probes. Appl. Environ. Micriobiol. 76 5282–5286 10.1128/AEM.00330-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raina J. B., Dinsdale E. A., Willis B. L., Bourne D. G. (2010). Do the organic sulphur compounds DMSP and DMS drive coral microbial associations? Trends Microbiol. 18 18101–18108 10.1016/j.tim.2009.12.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raina J. B., Tapiolas D., Willis B. L., Bourne D. G. (2009). Coral associated bacteria and their role in the biogeochemical cycling of sulfur. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 75 3429–3501 10.1128/AEM.02567-08 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richards G. P., Watson M. A., Needleman D. S., Church K. M., Hase C. C. (2015). Mortalities of eastern and pacfic oyster larvae caused by the pathogens Vibrio coralliilyticus and Vibrio tubiashii. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 81 292–297 10.1128/AEM.02930-14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ritchie K. B., Smith G. W. (1998). Type II white-band disease. Rev. Biol. Trop. 46 199–203. [Google Scholar]

- Ritchie K. B., Smith G. W. (2004). “Microbial communities of coral surface mucopolysaccharide layers,” in Coral Health and Disease Part II eds Rosenberg E., Loya Y. (Berlin: Springer; ) 259–264. [Google Scholar]

- Roder C., Arif C., Bayer T., Aranda M., Daniels C., Shibl A., et al. (2014). Bacterial profiling of white plague disease in a comparitive coral species framework. ISME J. 8 31–39 10.1038/ismej.2013.127 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rohwer F., Seguritan V., Azam F., Knowlton N. (2002). Diversity and distribution of coral-associated bacteria. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 243 1–10 10.3354/meps243001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenberg E., Falkovitz L. (2004). The Vibrio shiloi/Oculina patagonica model system of coral bleaching. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 58 143–159 10.1146/annurev.micro.58.030603.123610 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenberg E., Koren O., Reshef L., Efrony R., Zilber-Rosenberg I. (2007). The role of microorganisms in coral health, disease and evolution. Nat. Rev. 5 355–362 10.1038/nrmicro1635 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubio-Portillo E., Yarza P., Penalver C., Ramos-Espla A., Anton J. (2014). New insights into Oculina patagonica coral diseases and their associated Vibriio spp. Communities. ISME J. 8 1794–1807 10.1038/ismej.2014.33 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz-Morenol D., Willis B. L., Page A. C., Weil E., Croquer A., Vargas-Angel B., et al. (2012). Global coral disease prevalence associated with sea temperature anomalies and local factors. Dis. Aquat. Organ 100 249–261 10.3354/dao02488 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santos H. F., Carmo F. L., Duarte G., Dini-Andreote F., Castro C. B., Rosado A. S., et al. (2014). Climate change affects key nitrogen-fixing bacteriall populations on coral reefs. ISME J. 8 2272–2279 10.1038/ismej.2014.70 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santos Ede O., Alves N., Jr., Dias G. M., Mazotto A. M., Vermelho A., Vora G. J., et al. (2011). Genomic and proteomic analyses of the coral pathogen Vibrio coralliilyticus reveal a diverse virulence repetoire. ISME J. 5 1471–1483 10.1038/ismej.2011.19 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sato Y., Bourne D. G., Willis B. L. (2009). Dynamics of seasonal outbreaks of black band disease in an assemblage of Montipora species at Pelorus Island (Great Barrier Reef, Australia). Proc. R. Soc. B 276 2795–2803 10.1098/rspb.2009.0481 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shapiro R. L., Altekruse S., Hutwagner L., Bishop R., Hammond R., Wilson S., et al. (1998). The role of gulf coast oysters harvesred in warmer months in Vibrio vulnificus infections in the united states. J. Infect. Dis. 178 752–759 10.1086/515367 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sunagawa S., DeSantis T. Z., Piceno Y. M., Brodie E. L., DeSalvo M., Voolstra C. R., et al. (2009). Bacterial diversity and white plague disease-associated community changes in the Caribbean coral Montastraea faveolata. ISME J. 3 512–521 10.1038/ismej.2008.131 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sweet M. J., Croquer A., Bythell J. C. (2014). Experimental antibiotic treatment identifies potential pathogens of white band disease in the endangered Caribbean coral Acropora cervicornis. Proc. R. Soc. B 281:20140094 10.1098/rspb.2014.0094 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamura K., Dudley J., Nei M., Kumar S. (2007). MEGA4: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis (MEGA) software version 4.0. Mol. Biol. Evol. 24 1596–1599 10.1093/molbev/msm092 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamura K., Stecher G., Peterson D., Filipski A., Kumar S. (2013). MEGA6: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis version 6.0. Mol. Biol. Evol. 30 2725–2729 10.1093/molbev/mst197 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson F. L., Hoste B., Vandemeulebroecke K., Swings J. (2001). Genomic diversity amongst Vibrio isolates from different sources determinedby fluorescent amplified fragment length polymorphism. Syst. Appl. Microbiol. 24 520–538 10.1078/0723-2020-00067 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson J. R., Randa M. A., Marcelino L. A., Tomita-Mitchell A., Lim E., Polz M. F. (2004). Diversity and dynamics of a north atlantic coastal Vibrio community. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 70 4103–4110 10.1128/AEM.70.7.4103-4110.2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toren A., Landau L., Kushmaro A., Loya Y., Rosenberg E. (1998). Effect of temperature on adhesion of Vibrio strain AK-1 to Oculina patagonica and on coral bleaching. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 64 1379–1384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ushijima B., Smith A., Aeby G. S., Callahan S. M. (2012). Vibrio owensii induces the tissue loss disease Montipora white syndrome in the Hawaiian reef coral Montipora capitata. PLoS ONE 7:e46717 10.1371/journal.pone.0046717 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ushijima B., Videau P., Burger A. H., Shore-Maggio A., Runyon C. M., Sudek M., et al. (2014). Vibrio coralliilyticus strain OCN008 is an etiological agent of acute Montipora White Syndrome. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 80 2102–2109 10.1128/AEM.03463-13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Veal C. J., Carmi M., Fine M., Hoegh-Guldberg O. (2010). Increasing the accuracy of surface area estimation using single wax dipping of coral fragments. Coral Reefs 29 893–897 10.1007/s00338-010-0647-9 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Vega Thurber R., Willner-Hall D., Rodriguez-Mueller B., Desnues C., Edwards R. A., Angly F., et al. (2009). Metagenomic analysis of stressed coral holobionts. Environ. Microbiol. 11 2148–2163 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2009.01935.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vezzulli L., Brettar I., Pezzati E., Reid P. C., Colwell R. R., Hofle M. G., et al. (2012). Long-term effects of ocean warming on the prokaryotic community: evidence from the vibrios. ISME J. 6 21–30 10.1038/ismej.2011.89 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vezzulli L., Pezzati E., Huete-Stauffer C., Pruzzo C., Cerrano C. (2013). 16SrDNA pyrosequencing of the mediterranean gorgonian Paramuricea clavata reveals a link among alterations in bacterial holobiont members, anthropogenic influence and disease outbreaks. PLoS ONE 8:e67745 10.1371/journal.pone.0067745 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vezzulli L., Prevlatl M., Pruzzo C., Marchese A., Bourne D. G., Cerrano C., et al. (2010). Vibrio infections triggering mass mortality events in a warming Mediterranean Sea. Environ. Micribiol. 12 2007–2019 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2010.02209.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vidal-Dupiol J., Ladriere O., Meistertzheim A.-L., Foure L., Adjeroud M., Mitta G. (2011). Physiological responses of the scleractinina coral Pocillopora damicornis to bacterial stress from Vibrio coralliilyticus. J. Exp. Biol. 214 1533–1543 10.1242/jeb.053165 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yong L., Guanpin Y., Hualei W., Jixiang C., Xianming S., Guiwei Z., et al. (2006). Design of Vibrio 16S rRNA gene specific primers and their application in the analysis of seawater Vibrio community. J. Ocean Univ. China 5 157–164 10.1007/BF02919216 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.