Abstract

Most cases of Angelman syndrome (AS) result from loss or inactivation of ubiquitin protein ligase 3A (UBE3A), a gene displaying maternal-specific expression in brain. Epigenetic silencing of the paternal UBE3A allele in brain appears to be mediated by a non-coding UBE3A antisense (UBE3A-ATS). In human, UBE3A-ATS extends ∼450 kb to UBE3A from the small nuclear ribonucleoprotein N (SNURF/SNRPN) promoter region that contains a cis-acting imprinting center (IC). The concept of a single large antisense transcript is difficult to reconcile with the observation that SNURF/SNRPN shows a ubiquitous pattern of expression while the more distal part of UBE3A-ATS, which overlaps UBE3A, is brain specific. To address this problem, we examined murine transcripts initiating from several alternative exons dispersed within a 500 kb region upstream of Snurf/Snrpn. Similar to Ube3a-ATS, these upstream (U) exon-containing transcripts are expressed at neuronal stages of differentiation in a cell culture model of neurogenesis. These findings suggest the novel hypothesis that brain-specific transcription of Ube3a-ATS is regulated by the U exons rather than Snurf/Snrpn exon 1 as previously suggested from human studies. In support of this hypothesis, we describe U-Ube3a-ATS transcripts where U exons are spliced to Ube3a-ATS with the exclusion of Snurf-Snrpn. We also show that the murine U exons have arisen by genomic duplication of segments that include elements of the IC, suggesting that the brain specific silencing of Ube3a is due to multiple alternatively spliced IC-Ube3a-ATS transcripts.

INTRODUCTION

Prader–Willi syndrome (PWS) and Angelman syndrome (AS) are behavioral/neurological disorders of genomic imprinting that map to the chromosome 15q11–13 and chromosome 7C regions in human and mouse, respectively. PWS is caused by the absence of a normal paternal contribution to chromosome 15q11–q13 and is characterized by hypotonia and failure to thrive in infancy, small hands and feet, hypogonadism, variable mental retardation and hyperphagia that leads to a marked obesity (1). Paternally expressed transcripts in the PWS/AS region include both protein-encoding mRNAs and non-coding RNAs. The genes encoding small ribonucleoprotein N (SNURF/SNRPN), the neuronal growth suppressor NECDIN (NDN), makorin ring finger protein 3 (MKRN3) and the MAGE-like 2 protein (MAGEL2) are the best-characterized protein-encoding mRNAs in the PWS/AS region. Expression of the paternal-specific genes in the PWS region is controlled by an imprinting center (PWS-IC), a region of 4.3 kb that contains a differentially methylated region (PWS-DMR) within the SNURF/SNRPN promoter (2,3). The PWS-DMR is characterized by a maternal-specific pattern of DNA methylation; the proposed function of the PWS-IC is to control the switch from maternal to paternal imprint during spermatogenesis (4). Small paternally inherited deletions encompassing the PWS-IC cause PWS with extensive methylation of the PWS-DMR (5,6).

The clinical features of AS include severe mental retardation, ‘puppet-like’ ataxic gait with jerky arm movements, seizures, EEG abnormalities, hyperactivity and bouts of inappropriate laughter (7). The AS candidate gene, UBE3A (8,9), displays bi-allelic expression in most tissues but is maternal-specific in brain (10–12). The mechanism of epigenetic silencing of UBE3A has been associated with a brain specific paternal antisense (UBE3A-ATS) transcript in human and mouse (13–15). The opposite patterns of imprinted expression of UBE3A and UBE3A-ATS led us to propose that the antisense transcript functions in cis to repress the paternal allele of UBE3A in brain (16). Such a model would be consistent with the sense–antisense epigenetic mechanisms that regulate Xist as well other imprinted genes, including Igf2r (17,18).

In human, UBE3A-ATS is a large (∼460 kb) transcript that initiates in the PWS-IC and extends distally through SNURF/SNRPN, IPW and overlaps UBE3A (19). The non-coding UBE3A-ATS is alternatively spliced and serves as a host for several types of small nucleolar RNA (snoRNA) of the box C/D class that are contained within the introns and are expressed upon processing of the paternal copy of the host transcript (20–22). Here, we present evidence that the murine Ube3a-ATS is also a large (∼1000 kb) transcript that is alternatively processed. By following the in vitro neuronal differentiation of P19 embryonic carcinoma (EC) cells, we confirm that the distal region of Ube3a-ATS, that is host to the class MBII-52 snoRNAs and overlaps Ube3a, is detected during the initial stages of neurogenesis. In contrast, Snurf/Snrpn is expressed in undifferentiated precursor cells and throughout the course of differentiation. In order to understand the difference in temporal expression between the proximal and distal parts of Ube3a-ATS, we examined the transcription and organization of exons upstream (U) of Snurf/Snrpn that display paternal-specific expression in mouse (23). The U exon-containing transcripts display the same time course of expression as Ube3a-ATS during P19 neuronal differentiation and are brain specific and paternally expressed in mouse. There are at least 9 U exons in mouse and more than 30 highly homologous copies in rat. As is the case in human, the U exons appear to have arisen from genomic duplication of segments that include elements of the IC. These findings suggest that the U exons serve as initiation sites for IC-Ipw/Ube3a-ATS transcripts in brain.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

U-Snurf/Snrpn-Ipw-Ube3a-ATS genomic organization and alternative transcript expression

For RT–PCR analysis of Ube3a-ATS, total RNA was isolated from brain of adult wild-type C57 Bl/6J mice, of the PWS-IC deletion mouse (24) and wild-type littermate by using RNAzol (Tel-Test, Inc. Friendswood, TX) or TRIzol (Life Technologies, Gaithersburg, MD) according to the manufacturers' instructions. Total RNA was isolated from P19 cells at different time points of RA-induced neuronal differentiation by the cesium chloride gradient method. Reverse transcription reactions (+RT) were performed with 2.5 μg of RNA and Superscript reverse transcriptase (Life Technologies) using either random hexamer primers or the following antisense strand-specific primers: M-1F: 5′-TTTCACTTGATCCTTTTACAAACAAC-3′; M-2F: 5′-GCCTTCATAGTGTAATAGCAG-3′; M-3F: 5′-ATAGACAATCCAAAGTCTCCCC-3′; M-4F: 5′-GCACCTGTTGGAGGACTAGG-3′ and E-1F: 5′-CTGTTATTTCCTTTTGTGCACTG-3′. A 2.5 μg aliquot of total RNA was incubated in a similar manner but without reverse transcriptase (−RT) as a control. One-fifteenth of the +RT or −RT reaction was used in PCR reactions using either Advantage 2 Taq polymerase (Clontech) or Taq polymerase (Invitrogen) under conditions suggested by the manufacturer. Specific annealing temperatures and extension times are available upon request. Oligonucleotides for PCR were G1-1R (5′-TTCATGCTCACTAGGATTACGC-3′); G1-2R (5′-CTGGTGTTTTGCAATCATCTGAC-3′); L-1R (5′-ATCGAAAAAACAAGCTATCCAATC-3′); B-1R (5′-CATGGGCCATGAGTGACATCC-3′); M-5F (5′-TTTGGATTACTCATTGCTACATC-3′); M-6F (5′-TGGAATTACTATCCTTTGAGAGG-3′); E-2F (5′-CACTGTGCAATTTCTTTACAGTG-3′); 36B4-F (5′-TCTTCCAGGCTTTGGGCATC-3′); 36B4-R (5′-CCTCCGACTCTTCCTTTGCTTC-3′); 11-C (5′-AACTGAGGGTCAGTTTACTCT-3′); Ipw A2 (5′-TCTGCATGTTTTCCATGGACC-3′); 12-B (5′-AGATCATACATCATTGGGTTA-3′); IpwBC-F (5′-TCACCACAACACTGGACAAAAG-3′); IpwBC-R (5′-TGCTGCTACACAGGAAAGAGG-3′); U7a (5′-GGTCCTGCTCAGAGAAGAGC-3′); U7b (5′-CAGCAAGGCAATACAGCAAAT-3′); SnrpnEx1-F (5′-AGAGGGAGCCGGAGATGCC-3′); Delta (5′-GCCTGTCGGCCGTGGAGCA-3′); Atp10a-F (5′-AAAGTATCAAGTCCCACCGGC-3′); Atp10a-R (5′-AATCAAAAACATCAGACAGCTCG-3′); U5 (5′-GAGGCAGGCAAACATGCCTCT-3′). The oligonucleotide primers and PCR conditions for Nscl-2, NeuroD (25), Snrpn exon 7 (23), Snrpn exons 1–3 (26), Snrpn exons U1-3 and exons U2-3 (23), Gapdh (24) and Hprt (27) have been described previously.

For expression of MBII52 and MBII85 during P19 EC cell RA-induced neuronal differentiation, 5 μg of total RNA was size-fractionated on a 1.0% agarose/formaldehyde gel and transferred to a BioTrans nylon membrane (ICN Biochemicals, Irvine, CA). Hybridization was performed in ExpressHyb Hybridization Solution (Clontech, Palo Alto, CA) at 55°C with previously described MBII52 and MBII85 radiolabeled probes (20) and an Actin control probe furnished by the manufacturer. Washes were carried out according to the manufacturer's instructions. Membranes were exposed to Kodak BIOMAX film and autoradiographed for 3 days.

Sequencing and sequence analysis

Nucleotide sequencing was performed by the University of Connecticut Health Center Molecular Core Facility. Sequence data were processed and assembled using the Sequencher (Gene Codes, Ann Arbor, MI) program, version 4.1.2 and MacDNASIS (Hitachi Software, San Francisco, CA) version 3.7. Nucleotide sequence comparisons were performed using the BLAST (28) engines available at www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/blast/. Sequence alignments were performed using the Clustal algorithm in the MacVector 7.2 (Accelrys Inc, San Diego, CA) analysis package.

Differentiation of P19 cells

P19 EC cells were obtained from ATCC (Manassas, VA). P19 cells were maintained in Dulbecco's modified Eagle medium (DMEM, Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Hyclone, Logan, UT). For induction of neuronal differentiation (29,30), the cells were grown at a density of 106 per 100 mm bacteriological petri dish in 10 ml medium containing 5 × 10−7 M all-trans retinoic acid (T-RA. Calbiochem, La Jolla, CA) to promote aggregate formation. After 48 h, the aggregates were collected, partially disrupted by trypsinization, diluted 1:2 and plated again on bacteriological dishes in medium with RA. The aggregates were again trypsinized 48 h later and plated in medium without RA on tissue culture plates pre-coated with gelatin. Cytosine-B-d-arabinofuranoside at a concentration of 15 μg/ml (ara-C, Sigma Chemical Co., St Louis, MO) was added 24 h later to eliminate the cells that were still dividing and had not differentiated. At 5 days after addition of RA, the culture medium was changed to 50% Neurobasal media with B27 supplement, 50% DMEM (29).

RESULTS

Organization, processing and allele-specific expression of Ube3a-ATS

Multiple brain specific Ube3a-ATS transcripts are detected in the Ube3a to Snrpn interval (http://genome.ucsc.edu). Other antisense mRNAs are also known to map to this interval but the presence of a large gap in the sequence contig precludes a precise localization of the additional transcripts. The gap between Ube3a and Snrpn also prevents a display of the complete organization of Ipw. The putative Ube3a-ATS transcripts are all derived from brain cDNAs except for some of those covering the 5′ end of Snrpn. The Ube3a-ATS cDNAs span the entire Ube3a coding region with several mapping to beyond the 3′-untranslated region (3′-UTR) of Ube3a. In order to determine whether these transcripts are part of the antisense, we have analyzed the region of Ube3a-ATS that overlaps the Ube3a 3′-UTR and extends further downstream by strand-specific RT–PCR using a number of primer pair combinations. This analysis revealed that Ube3a-ATS transcription occurs throughout the ∼10 kb Ube3a 3′ end (Figure 1 and Table 1).

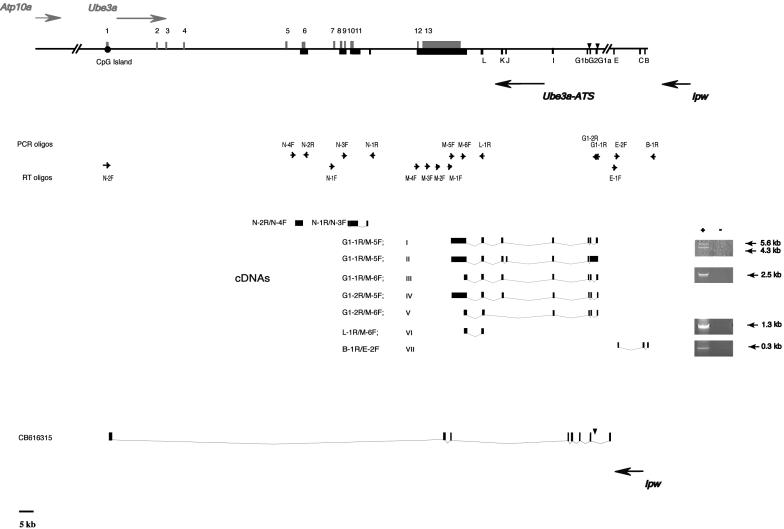

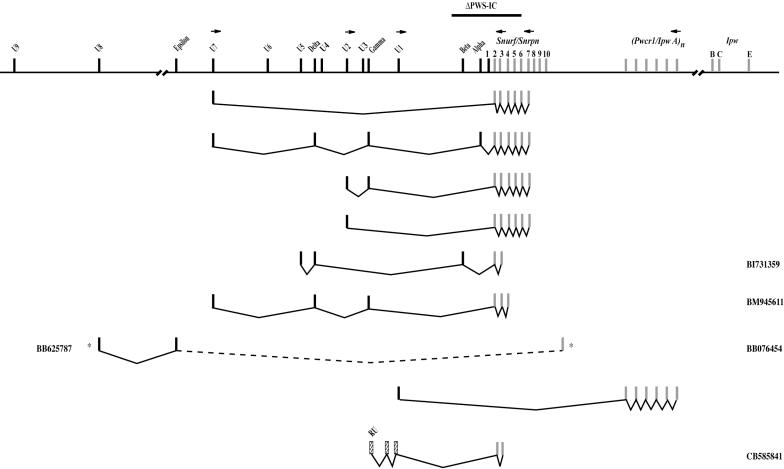

Figure 1.

Summary of RT–PCR analysis of Ube3a-ATS that overlaps Ube3a. The segments/exons of Ube3a and Ube3a-ATS are indicated above and below, respectively. Designation of Ube3a-ATS exons as I, J, K and L refers to their arbitrary assignment as alternative exons of Ipw. The positions of the oligos used for RT and PCR are indicated by small solid arrows. Filled triangles indicate positions of MBII-52/RBII-52 snoRNAs. PCR primers used for the detection of Ube3a-ATS are indicated. For the Ube3a-ATS N-1R/N-3F and N-2R/N-4F splice forms, RT oligos are N-1F and N-2F, respectively. For Ipw/Ube3a-ATS splice forms I through VII, RT oligos for each are I, II, IV and V, M-1F; III, random hexamer (RHex); VI, RHex, M-1F, M-2F, M-3F and M-4F; VII, RHex, M-1F and E-1F. One Ube3a antisense transcript from rat (GenBank accession no. CB616315) displays a unique pattern of splicing from the 3′- to 5′ ends of Ube3a. RT–PCR analyses performed using mouse brain RNA (+/− RT) are shown to the right of selected splice forms I and II (5.6 and 4.3 kb, M-1F), III (2.5 kb,), VI (1.3 kb) and VII (0.3 kb). The identity of all RT–PCR products was confirmed by nucleotide sequence analysis.

Table 1. Exon/intron organization of Ube3a-ATS.

| Exon | Nucleotide positiona | 3′ splice | Exon size (bp) | 5′ splice | Intron size (kb) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| G1a | 83058-82753 | — | 306 | TC/aggtaagtgaaaaa | 1.3 |

| G2 | 81447-81324 | ttccctttcctcctt/AG | 124 | AG/gtaagtggatggtt | 0.4 |

| G1b | 80944-80899 | tggtcttttttgca/GT | 46 | AG/gtatgtggaaagatc | 7.8 |

| I | 73023-72841 | cttacaattctag/AG | 183 | CA/aggtaacacctattc | 10.4 |

| J | 62398-62363 | taacaattttttgt/AG | 36 | CA/aggtaagcactctac | 0.8 |

| K | 61495-61406 | gtctctaaaaattc/AG | 90 | AA/gtaagtctggcgatt | 4.5 |

| L | 56930-56816 | taccctcctttcag/TT | 117 | TT/ggtaagtctgattag | 3.6 |

| Lb | 57019-56816 | ctcattctttttag/AA | 208 | TT/ggtaagtctgattag | 8.1 |

The nucleotide sequences of novel Ube3a-ATS RT–PCR products were compared to genomic database sequence to determine the splice consensus sites, exons and introns.

aGenBank accession no. AC027299.25.

bEST accession no. AK049008.

The RT–PCR analysis resulted in the identification of 4.3 and 5.6 kb amplification products (Figure 1, splice forms I and II) that contained 8 exons, distributed over 35 kb of genomic DNA (Figure 1, Table 1). Two exons (designated G1a and G1b) shared >80% nucleotide homology with the bipartite Ipw exon G1 (20,31) (Table 1, data not shown) while a third showed a similar level of identity to exon G2 (Table 1, data not shown). The difference in size between the 4.3 and 5.6 kb cDNAs obtained by RT–PCR (splice forms I and II, Figure 1) was due to the presence of an unprocessed MBII-52G1a cassette in the 5.6 kb splice form II cDNA. The other exons in the 4.3 and 5.6 kb cDNAs were designated Ipw exons I, J, K and L (Figure 1). To confirm that these exons are part of Ube3a-ATS, additional RT–PCRs were performed using different primer pair combinations (Figure 1, splice forms III–V).

We were also able to connect exon L to the antisense that overlaps the Ube3a 3′ end (Figure 1, 1.3 kb cDNA, splice form VI). A brain specific Ube3a-ATS splice form that contains exon L was also identified by a database search (GenBank accession no. AK049008). Ipw was also connected to Ube3a-ATS by performing RT–PCR using an RT oligo, M-2F, from the region overlapping the Ube3a 3′ end (Figure 1) and PCR primers specific for the upstream exons B and E (Figure 1, splice form VII) indicating that an upstream fragment of Ipw can be amplified by priming cDNA from the Ube3a 3′ end. We also attempted to link the region containing the novel Ipw exons to upstream Ipw exons B, C and E but we could not do so. The most likely explanation for this difficulty is that such transcripts potentially contain multiple copies of the bipartite exon G and cannot be amplified by RT–PCR due to their size and/or complex secondary structure. While the total number of G2-MBII-52-G1 cassettes in mouse cannot be determined because of the gaps in the Ipw to Ube3a contig, there are 47 HBII-52 containing cassettes in the human UBE3A-ATS (32).

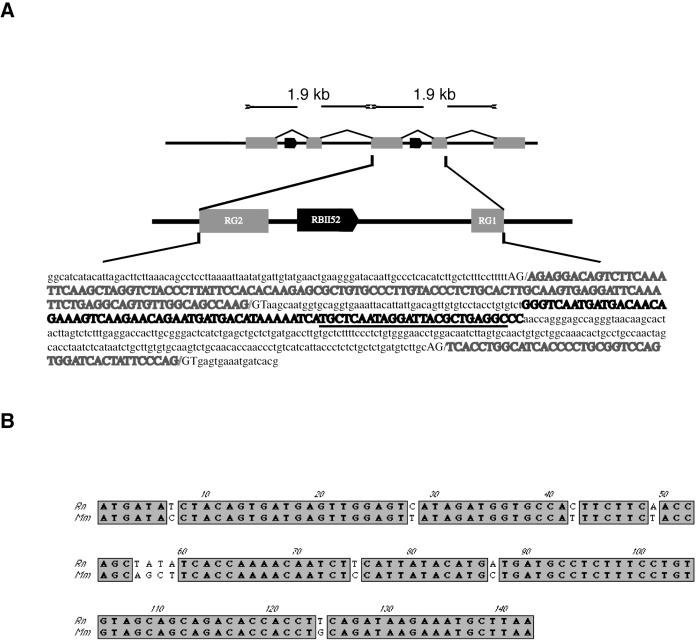

Additional support for the hypothesis that Ipw and Ube3a-ATS are part of the same transcript comes from the database retrieval of a cDNA clone (GenBank accession no. CB616315) from rat hypothalamus (Figure 1). The 5′ end of CB616315 contains six copies of Ipw G-like exons. Comparison of the genomic rat sequence to that of CB616315 reveals that the genomic structure is similar to that in mouse with G-like exons flanking introns that contain RBII-52 snoRNAs (Figure 2A). As observed between mouse and human (20), the rat and mouse BII-52 snoRNAs are almost 100% identical (Figure 2A). Although the size and organization of the rat RBII-52-containing cassettes (Figure 2A) are strikingly similar to that in mouse (20), the mouse and rat G exons are only ∼60% identical at nucleotide sequence level (data not shown). Sequence comparisons failed to identify Ipw exons B and E in the rat genome although exon C is highly conserved between mouse and rat (Figure 2B).

Figure 2.

Nucleotide sequence comparisons of Ipw exons/introns in rat and mouse. (A) Organization of a 1.9 kb rat Ipw exon G bipartite cassette containing Ipw exon RG1, a copy of an RBII-52 snoRNA and exon RG2. The size and structure of this cassette is highly similar to that previously reported in mouse (20) although the nucleotide similarity between the mouse and rat bipartite Ipw exons G is limited to ∼60%. The guide box of the RBII-52 snoRNA (underlined) is 100% identical to those of the MBII-52 and HBII-52 (human). (B) Nucleotide sequence comparison of Ipw exon C from mouse and rat.

The findings summarized above establish that the murine Ipw and Ube3a-ATS are part of the same transcript. When combined with the report that Snurf/Snrpn and Ipw are also a continuous transcript (33), the results suggest that, as previously postulated for human (19), Ube3a-ATS is a large transcript that extends from Snurf/Snrpn to Ube3a.

Expression of Ipw/Ube3a-ATS and snoRNAs during in vitro neurogenesis

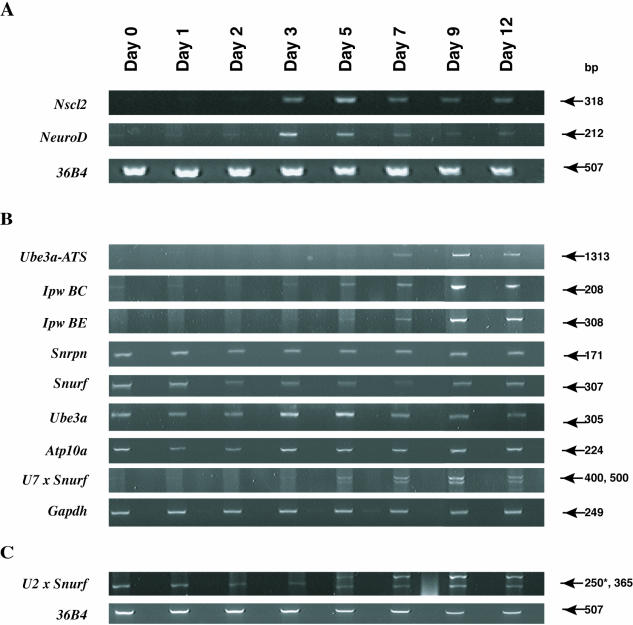

The expression levels of several transcripts from the AS/PWS region (Figure 3) were examined in P19 EC cells during the course of in vitro neurogenesis (29,30). Consistent with previous results (25,34), the neurogenic basic helix–loop–helix (bHLH) transcription factors, Nscl2 and NeuroD, are expressed transiently during P19 differentiation, with the peak levels of steady-state RNA observed between days 3 and 5 (Figure 3A). These temporal expression patterns for Nscl2 and NeuroD are consistent with the expected course of P19 neuronal differentiation (25,34). Ube3a-ATS transcription was assayed by RT–PCR using primers from Ipw exon L and from the region of overlap with the Ube3a 3′ end (Figure 1) and the transcript was detected at day 5 and with more marked expression at the later times of differentiation (Figure 3B). Similar results are obtained for a transcript containing Ipw exons B and E that correspond to the more proximal part of Ube3a-ATS (Figure 3B). Snurf, Snrpn, Ube3a and Atp10a, another protein-encoding transcript from the AS/PWS region (35,36), are expressed throughout the time course of differentiation (Figure 3). Gapdh and the 36B4 ribosomal gene display a relatively constant level of expression during P19 neurogenesis (34) and serve as internal controls. The data summarized in Figure 3 are consistent with the brain specific expression of the Ipw/Ube3a-ATS since expression of Ipw and Ube3a-ATS is first detectable at day 5 and up-regulated by day 7 of RA-induction, the time where P19 cells display neuronal-specific β tubulin J and neurite extensions (data not shown) (30,37).

Figure 3.

Gene expression during the time course of P19 neuronal differentiation. RT–PCR analysis of the neurogenic bHLH transcription factors Nscl2 and Neuro D, Ube3a-ATS (primers L-1R and M-6F), Ipw (BC and BE with primer pairs BC-R/BC-F and B-1R/E-2F, respectively), Snrpn, Snurf (primers SnrpnEx1-F and Snrpn exon 3), Ube3a and Atp10a, U7-Snurf (primers U7a and Snrpn exon 3) and U2-Snrpn exon 3 (a 250 bp non-specific product is indicated by the asterisk). Gapdh and 36B4 are used as controls. RT reactions are primed with RHex oligos.

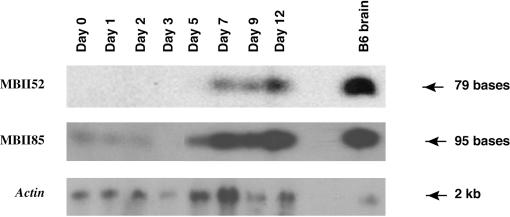

Processing of the Ipw/Ube3a-ATS host transcript in differentiating P19 cells should also result in the co-ordinate expression of the MBII-85 and MBII-52 classes of snoRNAs (19–22). In order to test expression of both these classes of snoRNA in P19 cells, northern blot hybridization was performed (Figure 4) using RNA samples from the P19 time course experiment in Figure 3. The results of Figure 4 show that, similar to the Ipw/Ube3a-ATS, MBII-52 snoRNA is first detectable at days 5–7 and increases markedly by day 9 of P19 neuronal induction, consistent with the previous report that MBII-52 displays brain-specific expression (20). Both classes of snoRNAs are highly expressed in total mouse brain (Figure 4). The faint MBII-85 expression at the earlier stages as well as in the undifferentiated cells (Figure 4) most likely represents a basal level of expression in P19 cells since we observe low-level expression of other neuronal-specific genes in undifferentiated P19 cells (D.L.B. and M.L., unpublished data).

Figure 4.

snoRNA expression during P19 time course. RNA from each time point (5 μg per lane) and from C57Bl6/J mouse brain was separated by agarose/formaldehyde gel electrophoresis. Northern blots were hybridized with MBII-52 and MBII-85 snoRNA oligomers as previously described (20). A β-actin probe is used as a control.

The markedly increased levels of Ube3a-ATS during neuronal differentiation occur in the absence of any significant augmentation of Snrpn and/or Snurf expression (Figure 3). While this observation is difficult to reconcile with the finding that Snrpn and Ube3a-ATS are part of the same transcript, it could suggest that there are neuronal-specific elements that regulate the expression of Snurf/Snrpn/Ipw/Ube3a-ATS. This led us to examine the organization and transcription of the exons upstream of Snrpn, including U2 and U7, that, similar to Ube3a-ATS, are up-regulated during the neuronal stages of P19 differentiation (Figure 3B and C).

Organization and expression of the U exons

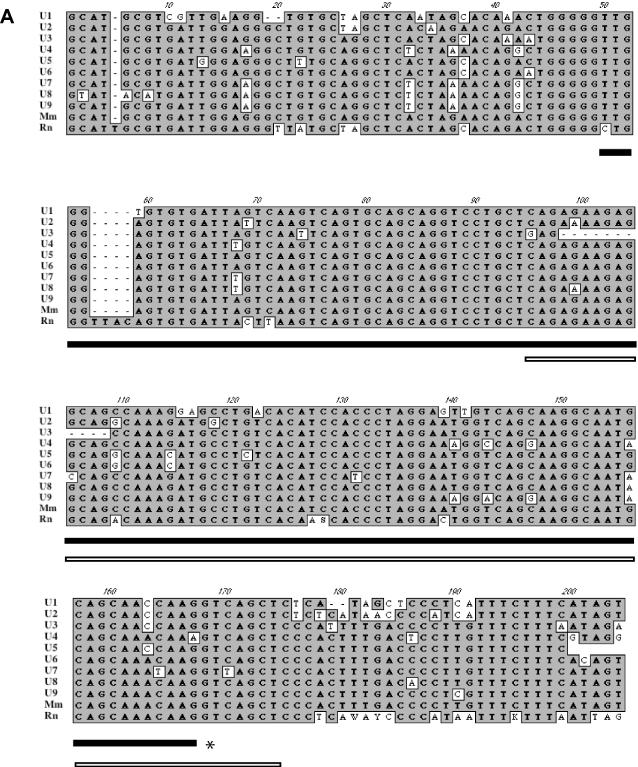

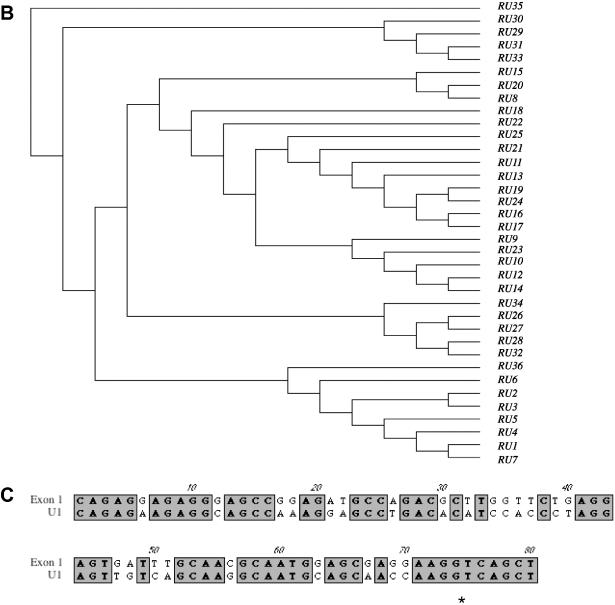

Transcripts containing exons U1 and U2, that lie upstream of the PWS-IC, splice to Snurf/Snrpn exon 2 and are paternal- and brain-specific (23). The availability of genomic sequence from the region upstream of Snrpn has allowed the in silico identification of nine additional U-like sequences (Figure 5A). The sequences of exons U1–U9 are highly homologous, with a conserved splice donor site but with no apparent splice acceptor consensus sequence (Figure 5A and Table 2). Two other U-like sequences were also identified that had lost the consensus splice donor sites, do not appear to be transcribed and are presumed to be pseudo U exons (Table 2) suggesting that these could represent the 5′ end of individual transcripts. The U1–U9 consensus sequence was used to perform homology searches of the rat genome, resulting in the identification of 36 highly homologous candidate U exons (Figure 5B). The consensus sequence derived for the 36 rat sequences shows >90% identity to the mouse U exon consensus sequence (Figure 5A). The neighbor joining analysis of the 36 copies of the rat U-like exons suggests that the murine U exons have arisen from multiple duplication events (Figure 5B). The U exons also show significant (∼70%) homology to Snurf/Snrpn exon 1 (Figure 5A and C) suggesting that conserved elements of the PWS-IC are duplicated in the upstream region.

Figure 5.

(A) Nucleotide sequence alignment of murine U exons. The bold bar underlines the U exon boundaries as defined previously for exons U1 and U2 (23) with remaining sequence corresponding to putative introns. Note the high degree of sequence identity in these putative introns. The U1–U9 consensus sequence (Mm) from mouse was used to identify highly homologous sequences from rat and a rat consensus (Rn) was derived. The asterisk denotes the conserved splice donor sequence. The open bar under the sequence indicates the region of homology with Snurf/Snrpn exon 1. (B) Rat exons designated RU1–RU36 were compared by joining tree analysis using ClustalW alignment algorithm in MacVector 7.1.1 (Accelrys). The data are consistent with a model of multiple duplications of the U exons. (C) Comparison of mouse U1 and Snrpn exon 1 (GenBank accession no. AF130843). The asterisk denotes the splice donor sequence.

Table 2. Conservation of donor splice site of U exons.

| Consensus sequence | Donor splice site | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C35 | A62 | G77 | g100 | t100 | a60 | a74 | g84 | |

| U1 | A | A | G | g | t | c | a | g |

| U2 | A | A | G | g | t | c | a | g |

| U3 | A | A | G | g | t | c | a | g |

| U4 | A | A | A | g | t | c | a | g |

| U5 | A | A | G | g | t | c | a | g |

| U6 | A | A | G | g | t | c | a | g |

| U7 | A | A | G | g | t | t | a | g |

| U8 | A | A | G | g | t | c | a | g |

| U9 | A | A | G | g | t | c | a | g |

| Pseudo-Ua | A | A | G | c | a | c | a | g |

| Pseudo-Ub | A | A | G | c | a | c | a | g |

The numbers given for the consensus sequence nucleotides specify the frequency of occurrence (%). Upper and lower case letters represent exonic and intronic nucleotides, respectively. Highly conserved nucleotides are shown in bold. The exons designated pseudo-Ua and-Ub, despite their homology to U exons, do not have splice donor consensus sequences and are unlikely to serve as transcription initiation sites.

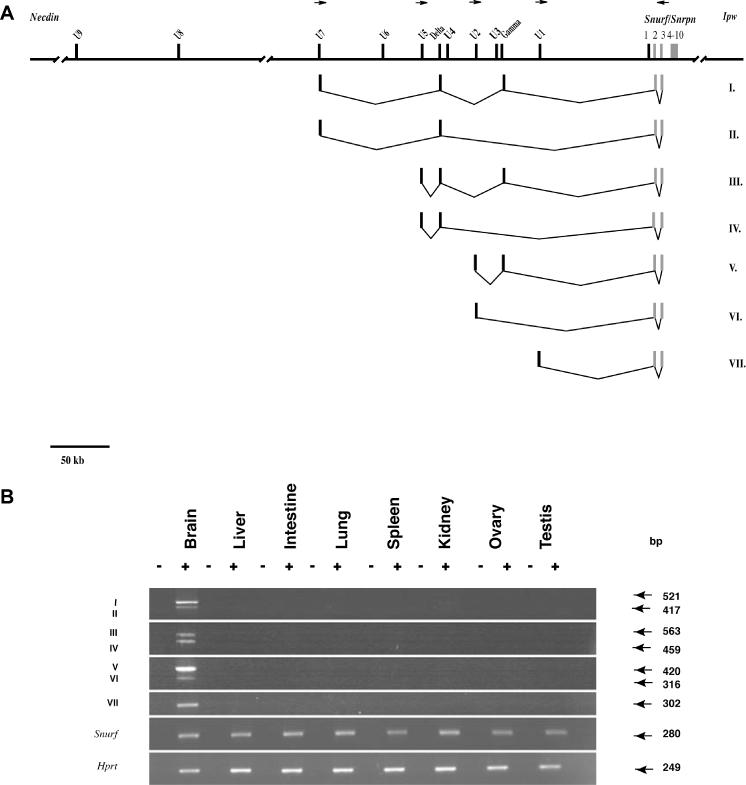

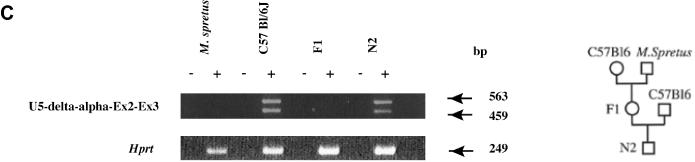

The organization of the mouse U exons is summarized in Figure 6A. As noted previously, transcripts containing the U1 and U2 exons splice to Snurf/Snrpn exon 2 (23). Transcripts containing exons U5 and U7 also splice to Snurf/Snrpn (Figure 6A). The additional exons designated gamma and delta are incorporated into the U-Snurf/Snrpn transcripts (Figure 6A). The expression of these novel U-Snurf/Snrpn transcripts was assayed in several different tissues and found to be exclusively present in brain (Figure 6B). We were able to determine the pattern of allele-specific expression of the novel U5-Snurf/Snrpn variant. A single nucleotide polymorphism in exon U5 was identified between Mus spretus and C57Bl6/J and used to design a C57Bl/6J allele-specific oligonucleotide. RT–PCR performed with this primer in a two-generation cross clearly shows that the U5 exon-containing transcripts are expressed exclusively from the paternal allele (Figure 6C).

Figure 6.

(A) Genomic organization of U exons and and brain transcription of U-Snurf/Snrpn transcripts. U1–U7 are distributed in a ∼250 kb contig upstream of Snurf/Snrpn. I–VII are splice variants of a selected subset of U-Snurf transcripts. Variants VI and VII have been previously described (23). Small horizontal arrows designate the position of oligonucleotide primers used for RT–PCR expression studies. (B) RT–PCR (+ or − RT) analysis demonstrating U2/U5/U7-Snrpn exon 3, Snurf (23) and Hprt expression control in eight mouse tissues (U7-specific primer is U7b). The numerals I to VII refer to the splice variants shown in (A). (C) Paternal expression of Snurf/Snrpn U5-3 transcript in mouse adult brain. RT–PCR analysis was performed for U5-exon 3 and a control gene, Hprt using RNAs isolated from adult brain of C57Bl6/J, M.spretus, (C57Bl6/J × M.spretus) F1 and [(C57Bl6/J × M.spretus) × C57Bl6/J] N2 mice. A C57Bl6/J-specific U5 primer (5′-GAGGCAGGC*(G)AAACATGCCTC*(G)T-3′ where the asterisk designates SNPs and M.spretus-specific nucleotides in parentheses) allows amplification only on RNA from the C57Bl6/J strain.

Additional expression analyses using brain RNA and database searches allowed the identification of additional novel transcripts and ESTs that contain exons U2, U5, U7 and U8 (Figure 7). These transcripts use additional alternative exons (beta, gamma, etc.) and splice to Snurf/Snrpn. U-Snurf/Snrpn transcripts from rat brain are also evident upon analysis of EST databases. These findings indicate that multiple brain specific U exons display a complex pattern of splicing to Snurf/Snrpn.

Figure 7.

Organization of alternative U exon-containing transcripts. The first four splice variants were identified by RT–PCR analysis of brain RNA (small horizontal arrows designate the position of oligonucleotide primers used in these experiments. EST clones are designated by the GenBank accession number. The ESTs designated by the asterisk are the 5′- and 3′ ESTs of clone 9330122E19 that has not been fully sequenced as indicated by the dashed line. The U-Snurf/Snrpn EST from rat (GenBank accession no. CB585841) is arbitrarily represented relative to the mouse upstream region. The extent of the 35 kb ΔPWS-IC is indicated by the solid horizontal line. Not drawn to scale.

Identification and regulation of U exon-Ube3a-ATS transcripts by the PWS-IC

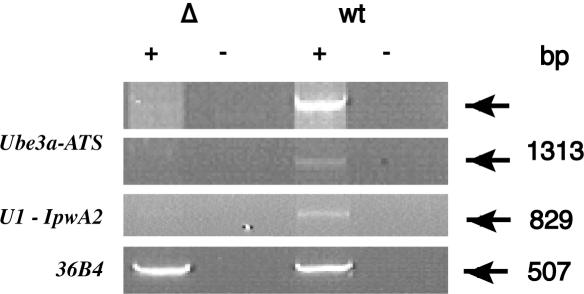

It was previously reported that, upon paternal transmission, the 35 kb PWS-IC deletion (ΔPWS-IC) abrogates the transcription of a Ube3a-ATS fragment overlapping Ube3a intron 8 (14). As shown in Figure 9, Ube3a-ATS spanning exon L and the Ube3a 3′-UTR is also under the control of the PWS-IC. We performed an RT–PCR using brain RNA and oligonucleotide primers in exon U1 and a reverse primer in Ipw exon A2 (31) (Figures 8 and 9). A product of 829 bp was detected in the brain of the normal littermate but not in that of the ΔPWS-IC. By nucleotide sequencing, the 829 bp cDNA consists of exon U1 and 6 copies of Ipw exon A2. These results not only indicate that the U1-Ipw A2 transcript is under the control of the PWS-IC but, also, that Ube3a-ATS transcripts initiating in a U exon can splice directly to Ube3a-ATS and exclude Snurf/Snrpn. In this regard, an EST containing exon U8 (BB625787; Figure 7) corresponds to nucleotide sequence from the 5′ end of a cDNA clone derived from diencephalon (GenBank accession no. 9330122E19). The 3′ EST of this cDNA clone (BB076454) maps to the interval beyond the Snrpn 3′-UTR, indicating that exon U8-containing transcripts also extend to beyond Snurf/Snrpn.

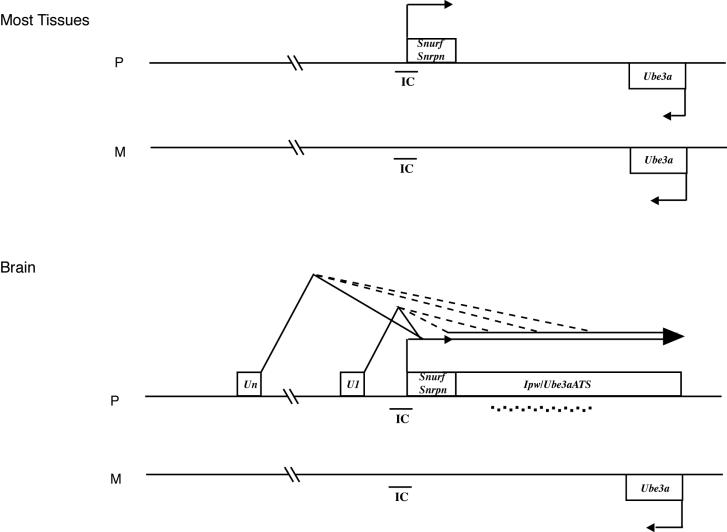

Figure 9.

Model for the control of brain specific expression of Ube3a-ATS by the U exons. In most tissues (top), transcription of Snurf/Snrpn is paternal while that of Ube3a is bi-allelic. During neurogenesis, expression of Ube3a-ATS is activated and initiates from a number of different U exons. Two classes of brain specific antisense transcript are generated. In one class, U exons are spliced to Snurf/Snrpn exon 2 generating antisense transcripts that include Snurf/Snrpn and extend further downstream. In the second class, Snurf/Snrpn is skipped and U exons splice to different downstream regions of Ube3a-ATS. Both classes undergo extensive processing that releases the brain specific snoRNAs (depicted by small squares). The presumed function of both classes of antisense transcript is to repress the paternal Ube3a allele.

Figure 8.

RT–PCR analysis of Ipw/Ube3a-ATS in brain from normal and ΔPWS-IC mice. RNA from PWS-IC deletion (Δ) and normal littermate (wt) mouse brain analyzed by RT–PCR. The PCR primers for Ube3a-ATS analysis are L-1R and M-6F (Figure 1). The U1, Ipw exon A2 and 36B4 primer pairs are described in the Materials and Methods. The oligonucleotides used for RT were the strand-specific M-2F in the top panel and random hexamers in the bottom three panels.

DISCUSSION

Deciphering the organization of the murine Ube3a-ATS as well as the mechanism of its brain-specific regulation are crucial to developing mouse models of the imprinting regulation of Ube3a. Such mouse models are particularly needed to define the structure and function of the IC in both mouse and human. The previous characterization of Ube3a-ATS was limited to a small region that overlaps Ube3a (14). Here, we demonstrate that, similar to the case in human (19), the Ube3a-ATS is part of a larger transcript that includes Ipw. In contrast to what has been reported in human, we present evidence that, in brain, Ube3a-ATS initiates in exons that are distributed throughout a 500 kb region upstream of Snurf/Snrpn, resulting in an antisense transcript that extends over a 1000 kb genomic region.

Alternative transcripts extending from Ipw exons G1 and G2 to the region of overlap with the Ube3a 3′ end (Figures 1 and 2) indicate that Ipw and Ube3a-ATS are part of the same transcript. The extensive nucleotide homology of the BII-52 snoRNAs and of Ipw exon C (Figure 2) confirms the conservation of the Ipw transcript between mouse and rat. The available sequence from the 3′ extent of the rat CB616315 EST overlaps the putative Ube3a exon 1 region suggesting that Ipw/Ube3a-ATS transcripts can extend to the Ube3a promoter. Ube3a-ATS transcripts that overlap the Ube3a promoter (see also AK038522, Figure 1) could function to regulate Ube3a by altering promoter activity or by other mechanisms that involve extensive sense–antisense overlap (38).

Our data also convincingly show that there is extensive processing of the Ipw/Ube3a-ATS in brain (Figure 1 and 2), a finding consistent with northern blot hybridization analysis of Ipw that yields a smear extending from 4 kb to at least 10 kb in size (39). Processing of the Ipw/Ube3a-ATS and expression of the MBII-52 and MBII-85 snoRNAs are detectable in the P19 in vitro model of neurogenesis. cDNAs containing exons B, C, and E and L of Ipw/Ube3a-ATS transcript as well as MBII-52 snoRNAs are first detectable at days 5–7 after induction of the P19 cells with retinoic acid (Figures 3 and 4). This co-ordinate temporal pattern of expression during in vitro neurogenesis is also consistent with Ipw and Ube3a-ATS being part of the same transcript. The P19 model system is quite useful for comparing the expression pattern of different transcripts from the AS/PWS region as a function of time after induction of neurogenesis. In particular, it is evident that Snurf/Snrpn shows no significant change in temporal expression pattern while Ipw, MBII-52 snoRNAs and Ube3a-ATS are detectable only by days 5–7 of P19 induction (Figures 4 and 5). These findings are consistent with the observation that expression of Ube3a-ATS is predominantly brain specific while Snurf/Snrpn is expressed in a wide range of tissues (Figure 6B).

The observation that the U2- and U7-Snurf/Snrpn transcripts show a time course of expression in P19 cells that is very similar to that of Ipw/Ube3a-ATS (Figure 3) raises the possibility that the U exons could function in the initiation of brain-specific Snurf/Snrpn/Ipw/Ube3a-ATS transcripts. Consistent with a potential function in transcript initiation, the U exons have highly conserved consensus splice donor site but no consensus splice acceptor site (Figure 6A, Table 2). In order to directly test our hypothesis, we performed an RT–PCR that connected exon U1 to Ipw exon A2 (Figure 8). The identification of this transcript, that splices out Snurf/Snrpn, demonstrates that brain-specific Ube3a-ATS transcripts can initiate from the U exons rather than from exon 1 as previously shown for the human UBE3A-ATS. A detailed in situ hybridization analysis of the U exon-containing transcripts and Ube3a-ATS confirm that there is extensive overlap in their tissue-specific and developmental expression, further supporting our hypothesis that Ube3a-ATS initiates from the U exons in brain (E. Le Meur and F. Muscatelli., manuscript in preparation). Our results argue for the existence of two classes of antisense transcript (Figure 9). Snurf/Snrpn is included in one class (Un-Snurf/Snrpn-Ube3a-ATS) but excluded from the second (Un-Ube3a-ATS).

We also demonstrate that deletion of the PWS-IC in brain abolishes expression of U1-Ipw A2 (Figure 8). Since the U1-Ipw A2 transcript splices out the 35 kb region that is deleted in the ΔPWS-IC (14,24) (Figure 7), this result demonstrates that U1–Ube3a-ATS transcripts are under the control of the IC. A smaller (4.8 kb) deletion encompassing the putative murine IC did not, however, affect the expression of a U1-Snurf/Snrpn transcript (23). The simplest interpretation of these results is that elements lying within the 35 kb but outside 4.8 kb PWS-IC deletions are required for establishing the paternal expression pattern of U exon-containing transcripts.

The organization and transcription of U-Snurf/Snrpn transcripts is also similar between mouse and rat (Figure 7) and there is significant sequence similarity between Snurf/Snrpn exon 1 and the U exons (Figure 5C). The region of homology includes three sequence elements of Snurf/Snrpn exon 1 that have been implicated as being required for the function of the bipartite IC (40). This is the first evidence to suggest that, as is the case in human (41), the murine IC has undergone multiple duplication events. In human, alternative transcripts initiate from exons (u) that are dispersed throughout the region upstream of SNURF/SNRPN although no UBE3A-ATS transcripts containing u exons have been reported (41,42). Molecular analysis of the micro-deletion in a subset of AS imprinting defect patients has allowed the delineation of the AS smallest region of overlap (AS-SRO) to a single 880 bp exon located 35–40 kb upstream of the PWS-IC (41). It has been proposed that the PWS-IC and AS-SRO represent the functional elements of a bipartite IC (43,44) and that the maternal AS-SRO functions in the methylation of PWS-IC (45). We speculate that the duplicated U exons contain functional elements of the murine ortholog of the AS-SRO. The disruption of U exons should allow the production of mouse models that will be crucial for characterizing the structure and function of the IC and for studying the mechanism of imprinting of Ube3a.

Acknowledgments

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors are grateful to Drs M. McBurney and B. Howell for providing reagents and advice on the P19 cells. This paper is dedicated to the memory of Dr Camilynn Brannan. This work was supported by NIH grants R01 NS30628 (M.L.) and F31 NS42490 (D.B.).

REFERENCES

- 1.Holm V.A., Cassidy,S.B., Butler,M.G., Hanchett,J.M., Greenswag,L.R., Whitman,B.Y. and Greenberg,F. (1993) Prader–Willi syndrome: consensus diagnostic criteria. Pediatrics, 91, 398–402. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sutcliffe J.S., Nakao,M., Christian,S., Orstavik,K.H., Tommerup,N., Ledbetter,D.H. and Beaudet,A.L. (1994) Deletions of a differentially methylated CpG island at the SNRPN gene define a putative imprinting control region. Nature Genet., 8, 52–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ohta T., Gray,T.A., Rogan,P.K., Buiting,K., Gabriel,J.M., Saitoh,S., Muralidhar,B., Bilienska,B., Krajewska-Walasek,M., Driscoll,D.J. et al. (1999) Imprinting-mutation mechanisms in Prader–Willi syndrome. Am. J. Hum. Genet., 64, 397–413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Buiting K., Saitoh,S., Gross,S., Dittrich,B., Schwartz,S., Nicholls,R.D. and Horsthemke,B. (1995) Inherited microdeletions in the Angelman and Prader–Willi syndromes define an imprinting centre on human chromosome 15. Nature Genet., 9, 395–400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bielinska B., Blaydes,S.M., Buiting,K., Yang,T., Krajewska-Walasek,M., Horsthemke,B. and Brannan,C.I. (2000) De novo deletions of SNRPN exon 1 in early human and mouse embryos result in a paternal to maternal imprint switch. Nature Genet., 25, 74–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.El-Maarri O., Buiting,K., Peery,E.G., Kroisel,P.M., Balaban,B., Wagner,K., Urman,B., Heyd,J., Lich,C., Brannan,C.I. et al. (2001) Maternal methylation imprints on human chromosome 15 are established during or after fertilization. Nature Genet., 27, 341–344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Williams C.A., Lossie,A. and Driscoll,D. (2001) Angelman syndrome: mimicking conditions and phenotypes. Am. J. Med. Genet., 101, 59–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kishino T., Lalande,M. and Wagstaff,J. (1997) UBE3A/E6-AP mutations cause Angelman syndrome. Nature Genet., 15, 70–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Matsuura T., Sutcliffe,J.S., Fang,P., Galjaard,R.J., Jiang,Y.H., Benton,C.S., Rommens,J.M. and Beaudet,A.L. (1997) De novo truncating mutations in E6-AP ubiquitin-protein ligase gene (UBE3A) in Angelman syndrome. Nature Genet., 15, 74–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Albrecht U., Sutcliffe,J.S., Cattanach,B.M., Beechey,C.V., Armstrong,D., Eichele,G. and Beaudet,A.L. (1997) Imprinted expression of the murine Angelman syndrome gene, Ube3a, in hippocampal and Purkinje neurons. Nature Genet., 17, 75–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rougeulle C., Glatt,H. and Lalande,M. (1997) The Angelman syndrome candidate gene, UBE3A/E6-AP, is imprinted in brain. Nature Genet., 17, 14–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vu T.H. and Hoffman,A.R. (1997) Imprinting of the Angelman syndrome gene, UBE3A, is restricted to brain. Nature Genet., 17, 12–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rougeulle C., Cardoso,C., Fontes,M., Colleaux,L. and Lalande,M. (1998) An imprinted antisense RNA overlaps UBE3A and a second maternally expressed transcript. Nature Genet., 19, 15–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chamberlain S.J. and Brannan,C.I. (2001) The Prader–Willi syndrome imprinting center activates the paternally expressed murine Ube3a antisense transcript but represses paternal Ube3a. Genomics, 73, 316–322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yamasaki K., Joh,K., Ohta,T., Masuzaki,H., Ishimaru,T., Mukai,T., Niikawa,N., Ogawa,M., Wagstaff,J. and Kishino,T. (2003) Neurons but not glial cells show reciprocal imprinting of sense and antisense transcripts of Ube3a. Hum. Mol. Genet., 12, 837–847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rougeulle C. and Lalande,M. (1998) Angelman syndrome: how many genes to remain silent? Neurogenetics, 1, 229–237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wutz A. and Barlow,D.P. (1998) Imprinting of the mouse Igf2r gene depends on an intronic CpG island. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol., 140, 9–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lee J.T., Davidow,L.S. and Warshawsky,D. (1999) Tsix, a gene antisense to Xist at the X-inactivation centre. Nature Genet., 21, 400–404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Runte M., Huttenhofer,A., Gross,S., Kiefmann,M., Horsthemke,B. and Buiting,K. (2001) The IC-SNURF-SNRPN transcript serves as a host for multiple small nucleolar RNA species and as an antisense RNA for UBE3A. Hum. Mol. Genet., 10, 2687–2700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cavaille J., Buiting,K., Kiefmann,M., Lalande,M., Brannan,C.I., Horsthemke,B., Bachellerie,J.P., Brosius,J. and Huttenhofer,A. (2000) Identification of brain-specific and imprinted small nucleolar RNA genes exhibiting an unusual genomic organization. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 97, 14311–14316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.de los Santos T., Schweizer,J., Rees,C.A. and Francke,U. (2000) Small evolutionarily conserved RNA, resembling C/D box small nucleolar RNA, is transcribed from PWCR1, a novel imprinted gene in the Prader–Willi deletion region, which is highly expressed in brain. Am. J. Hum. Genet., 67, 1067–1082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Meguro M., Mitsuya,K., Nomura,N., Kohda,M., Kashiwagi,A., Nishigaki,R., Yoshioka,H., Nakao,M., Oishi,M. and Oshimura,M. (2001) Large-scale evaluation of imprinting status in the Prader–Willi syndrome region: an imprinted direct repeat cluster resembling small nucleolar RNA genes. Hum. Mol. Genet., 10, 383–394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bressler J., Tsai,T.F., Wu,M.Y., Tsai,S.F., Ramirez,M.A., Armstrong,D. and Beaudet,A.L. (2001) The SNRPN promoter is not required for genomic imprinting of the Prader–Willi/Angelman domain in mice. Nature Genet., 28, 232–240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yang T., Adamson,T.E., Resnick,J.L., Leff,S., Wevrick,R., Francke,U., Jenkins,N.A., Copeland,N.G. and Brannan,C.I. (1998) A mouse model for Prader–Willi syndrome imprinting-centre mutations. Nature Genet., 19, 25–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Itoh F., Nakane,T. and Chiba,S. (1997) Gene expression of MASH-1, MATH-1, neuroD and NSCL-2, basic helix–loop–helix proteins, during neural differentiation in P19 embryonal carcinoma cells. Tohoku J. Exp. Med., 182, 327–336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tsai T.F., Armstrong,D. and Beaudet,A.L. (1999) Necdin-deficient mice do not show lethality or the obesity and infertility of Prader–Willi syndrome. Nature Genet., 22, 15–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Boccaccio I., Glatt-Deeley,H., Watrin,F., Roeckel,N., Lalande,M. and Muscatelli,F. (1999) The human MAGEL2 gene and its mouse homologue are paternally expressed and mapped to the Prader–Willi region. Hum. Mol. Genet., 8, 2497–2505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Altschul S.F., Madden,T.L., Schaffer,A.A., Zhang,J., Zhang,Z., Miller,W. and Lipman,D.J. (1997) Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST: a new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Res., 25, 3389–3402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bain G., Yao,M., Huettner,J.E., Finley,M.F. and Gottlieb,D.I. (1998) Neuron-like cells derived in culture from P19 embryonal carcinoma and embryonic stem cells. In Banker,G. and Goslin,K. (eds), Culturing Nerve Cells, 2nd edn. The MIT Press, Cambridge, MA, pp. 188–211. [Google Scholar]

- 30.McBurney M.W., Reuhl,K.R., Ally,A.I., Nasipuri,S., Bell,J.C. and Craig,J. (1988) Differentiation and maturation of embryonal carcinoma-derived neurons in cell culture. J. Neurosci., 8, 1063–1073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wevrick R. and Francke,U. (1997) An imprinted mouse transcript homologous to the human imprinted in Prader–Willi syndrome (IPW) gene. Hum. Mol. Genet., 6, 325–332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Runte M., Kroisel,P.M., Gillessen-Kaesbach,G., Varon,R., Horn,D., Cohen,M.Y., Wagstaff,J., Horsthemke,B. and Buiting,K. (2004) SNURF-SNRPN and UBE3A transcript levels in patients with Angelman syndrome. Hum. Genet., 114, 553–561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mapendano K., Kishino,T., Niikawa,N., Nicholls,R.D. and Ohta,T. (2003) Isolation of a mouse snoRNA host gene from the Snurf-Snrpn locus and association with imprint establishment. Am. J. Hum. Genet., S73, 334. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Boudjelal M., Taneja,R., Matsubara,S., Bouillet,P., Dolle,P. and Chambon,P. (1997) Overexpression of Stra13, a novel retinoic acid-inducible gene of the basic helix–loop–helix family, inhibits mesodermal and promotes neuronal differentiation of P19 cells. Genes Dev., 11, 2052–2065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Meguro M., Kashiwagi,A., Mitsuya,K., Nakao,M., Kondo,I., Saitoh,S. and Oshimura,M. (2001) A novel maternally expressed gene, ATP10C, encodes a putative aminophospholipid translocase associated with Angelman syndrome. Nature Genet., 28, 19–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Herzing L.B., Kim,S.J., Cook,E.H.,Jr and Ledbetter,D.H. (2001) The Human Aminophospholipid-Transporting ATPase Gene ATP10C Maps Adjacent to UBE3A and Exhibits Similar Imprinted Expression. Am. J. Hum. Genet., 68, 1501–1505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bain G. and Gottlieb,D.I. (1998) Neural cells derived by in vitro differentiation of P19 and embryonic stem cells. Perspect. Dev. Neurobiol., 5, 175–178. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shibata S. and Lee,J.T. (2003) Characterization and quantitation of differential Tsix transcripts: implications for Tsix function. Hum. Mol. Genet., 12, 125–136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gerard M., Hernandez,L., Wevrick,R. and Stewart,C.L. (1999) Disruption of the mouse necdin gene results in early post-natal lethality. Nature Genet., 23, 199–202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kantor B., Makedonski,K., Green-Finberg,Y., Shemer,R. and Razin,A. (2004) Control elements within the PWS/AS imprinting box and their function in the imprinting process. Hum. Mol. Genet., 13, 751–762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Farber C., Dittrich,B., Buiting,K. and Horsthemke,B. (1999) The chromosome 15 imprinting centre (IC) region has undergone multiple duplication events and contains an upstream exon of SNRPN that is deleted in all Angelman syndrome patients with an IC microdeletion. Hum. Mol. Genet., 8, 337–343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Dittrich B., Buiting,K., Korn,B., Rickard,S., Buxton,J., Saitoh,S., Nicholls,R.D., Poustka,A., Winterpacht,A., Zabel,B. et al. (1996) Imprint switching on human chromosome 15 may involve alternative transcripts of the SNRPN gene. Nature Genet., 14, 163–170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Shemer R., Hershko,A.Y., Perk,J., Mostoslavsky,R., Tsuberi,B., Cedar,H., Buiting,K. and Razin,A. (2000) The imprinting box of the Prader–Willi/Angelman syndrome domain. Nature Genet., 26, 440–443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Buiting K., Barnicoat,A., Lich,C., Pembrey,M., Malcolm,S. and Horsthemke,B. (2001) Disruption of the bipartite imprinting center in a family with Angelman syndrome. Am. J. Hum. Genet., 68, 1290–1294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Perk J., Makedonski,K., Lande,L., Cedar,H., Razin,A. and Shemer,R. (2002) The imprinting mechanism of the Prader–Willi/Angelman regional control center. EMBO J., 21, 5807–5814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]