Abstract

Oncolytic virotherapy shows promise for pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC) treatment, but there is the need to minimize associated-toxicities. In the current work, we engineered artificial target sites recognized by miR-216a and/or miR-148a to provide pancreatic tumor-selectivity to replication-competent adenoviruses (Ad-miRTs) and improve their safety profile. Expression analysis in PDAC patients identified miR-148a and miR-216a downregulated in resectable (FCmiR-148a = 0.044, P < 0.05; FCmiR-216a = 0.017, P < 0.05), locally advanced (FCmiR-148a = 0.038, P < 0.001; FCmiR-216a = 0.001, P < 0.001) and metastatic tumors (FCmiR-148a = 0.041, P < 0.01; FCmiR-216a = 0.002, P < 0.001). In mouse tissues, miR-216a was highly specific of the exocrine pancreas whereas miR-148a was abundant in the exocrine pancreas, Langerhans islets, and the liver. In line with the miRNA content and the miRNA target site design, we show E1A gene expression and viral propagation efficiently controlled in Ad-miRT-infected cells. Consequently, Ad-miRT-infected mice presented reduced pancreatic and liver damage without perturbation of the endogenous miRNAs and their targets. Interestingly, the 8-miR148aT design showed repressing activity by all miR-148/152 family members with significant detargeting effects in the pancreas and liver. Ad-miRTs preserved their oncolytic activity and triggered strong antitumoral responses. This study provides preclinical evidences of miR-148a and miR-216a target site insertions to confer adenoviral selectivity and proposes 8-miR148aT as an optimal detargeting strategy for genetically-engineered therapies against PDAC.

Introduction

Pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC) is characterized by the accumulation of a high number of gene deletions, amplifications or mutations and alterations in miRNA (miRNA or miR) expression. miRNAs are noncoding RNAs that negatively regulate gene expression by binding to complementary sites of their target mRNAs resulting in translation inhibition. In the last decade, significant works highlighted the impact of miRNA deregulation in PDAC. Important roles in tumorigenesis, invasiveness, and resistance to chemotherapies have been assigned to different miRNAs.1 Moreover, the central role of miRNAs in cell homeostasis and tissue-specific expression profiles has envisaged their utility as discriminators of cancer from noncancerous tissues.2 MiRNA signatures exhibited distinctive expression variations in pancreatic tumor samples, chronic pancreatitis, and normal pancreas.3,4,5 All the novel insights of miRNAs in PDAC can constitute the basis for the design of new therapeutic approaches.

PDAC is a difficult neoplasia to treat. New therapies based on targeting components of abnormal pathways have not produced much success, and chemotherapeutic treatments, such as gemcitabine or folfirinox and more recently the combination of gemcitabine and nab-paclitaxel remain the standard therapies. Despite clinical improvement has been achieved with such treatments,6,7 tumor recurrence and the strong associated toxicities with folfirinox highlight the necessity to continue investigating for better therapies. Genetic vaccines, gene therapy or oncolytic virotherapies constitute a group of experimental therapies from which PDAC patients may benefit in the near future. For all these developing molecular engineered therapies, the specificity of targeting neoplastic cells is extremely important to preserve normal cell function in nontumoral tissues. Endogenous miRNA can be harnessed as specific cellular regulators to modulate the expression of engineered nucleic acids.8 Moreover, exploiting miRNA deregulation in tumors has gained interest to modify virus tropism.9,10,11,12,13,14

Oncolytic adenoviruses can be engineered to specifically target, replicate in, and eliminate cancer cells. The treatment of pancreatic cancer with oncolytic adenoviruses capable of preserving normal pancreatic function of the nonneoplastic pancreas, may be a potent anticancer approach offering patients with increased life quality. Since miRNAs are distinctly expressed in the differentiated cells of the pancreas, and miRNA signatures can be identified in PDAC. We reasoned that pancreatic miRNA-selective adenovirus could be promising agents to act against pancreatic cancer without risking viral-associated toxicity in normal tissue. Treatment of advance-stage pancreatic tumors would require systemic administration of the oncolytic virus. In recent years, intravenous delivery of Ad5 adenovirus has been shown to lead enhanced hepatocyte transduction predominantly mediated by a direct Ad5 hexon-Factor X interaction what results in notorious liver damage.15,16 Reducing the expression of adenoviral proteins in the liver can limit the toxicity.17 Accordingly, oncolytic adenoviruses with the normal liver and pancreas detargeting are highly desirable.

Here, we address the use of engineered target sites recognized by hallmark miRNAs in the pancreas and liver to control viral genes in the adenovirus genome, and we evaluate for the selectivity of the virus and its antitumoral capacity. Furthermore, we extend our studies to analyze potential unwanted cellular consequences that could limit miRNA activity in normal cells. Collectively, these studies describe miR-148a and miR-216a-engineered adenoviruses to efficiently control E1A expression in a miR-dependent manner, limiting pancreas, and liver damage while preserving active replication and antitumoral activity in pancreatic cancer cells. Moreover, we show the contribution to detargeting effects of all miR-148/152 family members.

Results

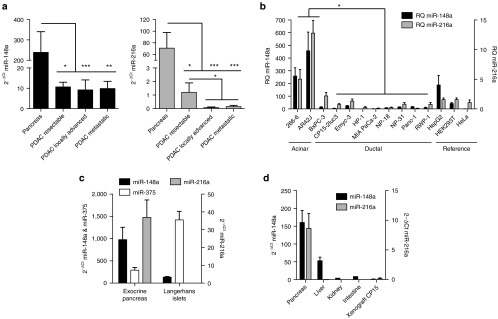

miR-148a and miR-216a are abundantly expressed in human and rodent pancreas but are lost in PDAC

Array-based miRNA profiling from the published data of independent studies identified miR-148a and miR-216a downregulated in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma.3,18 To confirm the downregulation of such miRNAs in all PDAC stages, we performed quantitative RT-PCR (RT-qPCR) in a set of primary tumor tissues obtained from PDAC patients either from surgical resection or from endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspiration biopsies, in both cases prior to chemotherapy administration. This set consisted of tumors classified as resectable, locally advanced, metastatic, and a control group of normal pancreas. RT-qPCR confirmed that miR-148a-3p and miR-216a-5p content was significantly reduced in resectable PDAC tumors versus healthy tissue, and showed that this reduction was maintained in more advanced stages as in locally advanced and metastatic tumors. Interestingly, miR-216a reduction was significantly more pronounced in advanced tumoral stages (Figure 1a). Low expression was also observed in a battery of cell lines of pancreatic cancer, but significantly higher expression was detected in the pancreatic acinar tumor 266-6 and AR42J cells (Figure 1b). In mouse pancreas, we analyzed the presence of both miRNAs together with miR-375, a well-known miRNA present in the Langerhans islets. We observed that miR-375 and miR-148a were much more abundant than miR-216a. All three were detected in the exocrine part of the pancreas but only miR-375 and miR-148a were present in the Langerhans islets (Figure 1c). This is in line with the high abundance of miR-375 and miR-148a detected in the miRNA sequencing profile of human pancreatic islets.19 In addition to the pancreas, miR-148a was also found expressed in the mouse liver, although at lower levels, but not in the kidney or intestine. MiR-216a was only detected in the pancreas (Figure 1d). Together, all these data confirm the lost of miR-148a and miR-216a in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinomas and reveal their abundance in healthy pancreas.

Figure 1.

miR-216a and miR-148a are downregulated in Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma (PDAC). (a). RT-qPCR expression of miR-148a (left panel) and miR-216a (right panel) in a cohort of patients with resectable (n = 9), locally advanced (n = 8) or metastatic tumors (n = 9) at diagnosis. Control pancreas was obtained from non-tumor areas of the same individuals or from healthy individuals (n = 11). * and *** denote P < 0.05 and P < 0.001, respectively. (b) RT-qPCR expression of miR-216a and miR-148a in a set of pancreatic and reference cell lines. Values represent mean ± SEM of four independent samples. * denote P < 0.05. (c) RT-qPCR expression of miR-375, miR-216a, and miR-148a in mice isolated exocrine pancreas and Langerhans islets. Values represent mean ± SEM of four independent samples. (d) RT-qPCR expression of miR-148a, miR-216a in mouse tissues (pancreas, liver, kidney, intestine) and in a xenograft model of PDAC. Samples were obtained from three individuals and values represent mean ± SEM.

miR-148a and miR-216a selectively control E1A expression and viral replication

The pancreatic expression of miR-148a and miR-216a and the observations of their lost in PDAC prompted us to hypothesize that oncolytic adenoviruses could be selectively controlled by miR-148a and miR-216a. First, to assess their transgene repression capacity, we inserted in the 3'UTR of luciferase reporter plasmids four (pLuc-miR216aT or pLuc-miR148aT), eight (pLuc-miR148a148aT) or four plus four (pLuc-miR148a216aT) target sites perfectly complementary to the regulator miRNAs (Figure 2a, Supplementary Figure S1a). Cotransfection of the reporter plasmids with p-miR-216a or p-miR-148a (Supplementary Figure S1b) expressing vectors in HeLa cells led to a reduction in luciferase expression. Increased reduction was obtained with plasmids containing eight target sites with a similar response between those engineered with 8-miR148aT or those with 4-miR148aT+4-miR216aT (Figure 2b). Similar results were observed in the pancreatic cancer cell line RWP-1 (Supplementary Figure S1c). The inhibition was specific because no reduction in transgene expression was observed when pLuc-miR216aT and p-miR-148a or pLuc-miR148aT and p-miR-216a were cotransfected (Supplementary Figure S1d).

Figure 2.

E1A expression and viral production are regulated by miR-148a and/or miR-216a content in cells infected with the engineered Ad-miRT. (a) Scheme of sequence alignment of miR-148a and miR-216a to the corresponding miR target sites engineered in the luciferase vectors. (b) Luciferase activity in HeLa cells cotransfected with the reporter plasmids and miR-216a and miR-148a expression vectors. Values represent mean ± SEM of four independent experiments. * denote P < 0.05. (c) Schematic representation of engineered adenoviruses, Ad-miR148aT, Ad-miR148a148aT, Ad-miR148a216aT. (d) Representative Western blots of E1A from cells infected with the different viruses at 10 vp/cell (MIA PaCa-2 miR-148a, MIA PaCa-2 miR-SC, and RWP-1), 100 vp/cell (266-6) and 1,000 vp/cell (AR42J). (e) Quantification of viral production in cells infected with the different viruses at the above indicated doses. Data is shown as the mean ± SEM of four independent experiments. * and ns denote P < 0.05 and no significant difference, respectively.

Based on the previous results, we decided to generate three different miR-targeted adenoviruses Ad-miR148aT (Ad-4miRT), Ad-miR148a148aT and Ad-miR148a216aT (Ad-8miRT) on a background of wild-type Ad5 (Figure 2c) in which miRNA target sites were engineered at the 3'UTR of the E1A gene. To test the selective capacity of the different adenoviruses, we infected miR-148a and miR-216a positive and negative cells and MIAPaCa-2 cells stably expressing miR-148a (MIAPaCa-2 miR-148a), or seed-scrambled miR-148a (MIAPaCa-2 miR-SC) (Supplementary Figure S1e). Ad5 wild-type (Ad-wt) was used as control virus.

The data show that E1A protein expression was tightly regulated in line with miRNA content. A strong inhibition was observed in MIAPaCa-2 miR-148a cells; by the three viruses whereas no effect was detected in MIAPaCa-2 miR-SC cells neither in miR-148a nor miR-216a double negative RWP-1 cell line. Noticeable, E1A downregulation was also observed in cell lines expressing endogenous levels of miR-148a and miR-216a (Figure 2d).

Then, we examined whether miR-148a and miR-216a content influenced viral replication. All miR-targeted adenoviruses significantly suppressed viral replication in MIAPaCa-2 miR-148a cells and in the miR-148a and miR-216a positive cells AR42J cells. Comparable viral replication to Ad-wt was observed in the miR-148a and miR-216a negative MIAPaCa-2 miR-SC and RWP-1cells (Figure 2e).

To evaluate in mouse pancreas whether miR-148a and miR-216a could successfully control oncolytic adenoviruses we injected (2 × 1010 vp/mouse) of Ad-wt, Ad-miR148aT, Ad-miR148a148aT and Ad-miR148a216aT into the common bile duct of C57BL/6 mice. We selected this route of administration as we have previously shown to be a highly efficient approach to deliver adenovirus to the pancreas.20 Three days after viral administration, E1A expression and the presence of viral genomes were analyzed. E1A was highly expressed in the pancreas of mice receiving Ad-wt, both at the protein and mRNA levels. Interestingly, a highly significant reduction in E1A expression was observed in the groups receiving Ad-miRT-controlled viruses (Figure 3a,c). E1A was present both in the exocrine and in the Langerhans islets of Ad-wt-infected pancreas as shown by E1A immunostaining, indicating that by intraductal delivery adenoviruses reached both exocrine and endocrine pancreatic fraction. E1A in Ad-miR148aT-treated mice was less detected in the exocrine, but similarly in endocrine when compared to Ad-wt, whereas Ad-miR148a148aT and Ad-miR148a216aT-treated pancreas showed a significant reduction in the number of positive cells in both pancreatic areas (Figure 3b).

Figure 3.

Ad-miR148aT, Ad-miR148a148aT, Ad-miR148a216aT activities are controlled by pancreatic miR-148a and miR-216a after intraductal delivery. (a) Representative western blots of E1A in pancreatic tissue extracts from wild type mice intraductally injected with 2.1010 vp/mice of the different viruses. Quantification of E1A signal normalized to Gapdh expression (n = 6). Values are expressed relative to E1A content from Ad-wt treated mice. (b) Representative images of E1A immunostaining in infected pancreas. Quantification of E1A-positive cells per area in exocrine pancreas (n = 30 sections/treatment) and Langerhans islets (n = 30 islets/treatment). ** denote P < 0.01. (c) Relative expression of E1A compared to Ad-wt assessed by RT-qPCR in total pancreatic tissue extracts of injected mice (n = 6). * and ** denote P < 0.05 and P < 0.01, respectively. (d) Viral replication in pancreas assessed by genomic qPCR of the L3 gene (n = 6). ** denote P < 0.01.

Despite the impairment of human Ad5 to productively replicate in mice, certain level of replication has been reported in the mouse liver.9 We investigated whether miRNA-controlled adenoviruses could attenuate viral replication in the pancreas. Mice intraductally injected with Ad-wt presented an average of 9 × 107 genomes/mg pancreas, that represent approximately a twofold increase in genome copies compared to the total amount of virus injected, suggesting some degree of replication. The presence of four target sites for miR-148a-controlling E1A did not seem to have any effect controlling viral replication. In contrast, Ad-miR148a148aT and Ad-miR148a216aT showed 5 × 107 and 4 × 107genomes/mg pancreas, respectively, similar to the input dose, indicating lack of replication (Figure 3d). Adenoviral genome integrity of miRNA target sites in the infected pancreas was confirmed by specific PCR amplification (Supplementary Figure S2).

These data confirm that miR-148a and miR-216a suppression of E1A can significantly reduce viral replication in the mouse pancreas. Noticeable, in the in vivo setting, this effect was only observed when eight target-binding sites were controlling E1A either recognizing only miR-148a or both miR-148a and miR-216a.

Since miR-148a was also present in the mouse liver and adenoviruses have an extreme tropism for hepatocyte infection after its intravascular delivery, we sought to evaluate the capacity of Ad-miR148a148aT to detarget adenovirus from the liver.

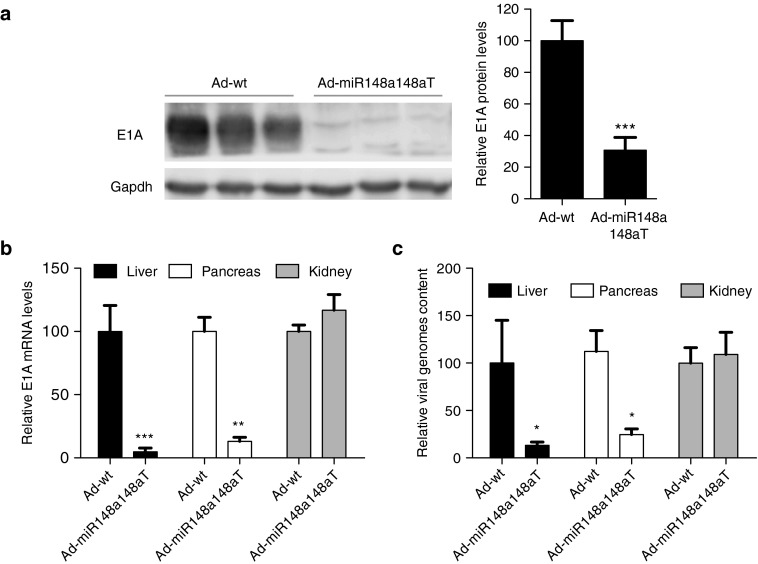

Three days after viral administration, E1A expression was analyzed by western blot in the liver of mice treated with Ad-wt or Ad-miR148a148aT at 2 × 1010 vp/mouse. E1A protein in Ad-miR148a148aT livers was extremely low when compared to Ad-wt (Figure 4a). Quantitative analysis of E1A mRNA in the liver, pancreas, and kidney of Ad-miR148a148aT-injected mice showed reduced mRNA content in the liver and pancreas but not in the kidney, in line with miR-148a expression (Figure 4b). Similar results were obtained with the analysis of the viral genomes (Figure 4c).

Figure 4.

Ad-miR148a148aT activity is controlled by miR-148a in liver and pancreas after systemic delivery. (a) Representative western blots of E1A in liver extracts from wild type mice intravenously injected with Ad-wt (n = 10) and Ad-miR148a148aT at 2.1010 vp/mice (n = 10). *** denote P < 0.001. (b) Relative expression of E1A compared to Ad-wt assessed by RT-qPCR in liver, pancreas and kidneys (n = 10/treatment). * and ** denote P < 0.05 and P < 0.01, respectively. (c). Relative viral replication compared to Ad-wt assessed by genomic qPCR of the L3 gene in liver, pancreas and kidneys (n = 10/treatment). * denote P < 0.05.

MiR-148a, miR-148b, and miR-152 are the three members of the miR-148/152 family, and all three miRNAs are expressed in the mouse and human liver and pancreas (Supplementary Figure S3a,b). We hypothesized that the remarkable detargeting of Ad-miR148a148aT could rely not only on the effects of miR-148a but also on the miR-148b and miR-152 contribution. Despite there is no full complementarity between the 8-miR148aT-engineered target sites and miR-148b and miR-152, complementarity comprises the seed region and an expanded 3'-supplementary site (Figure 5a). By using the RNAhybrid algorithm developed by Rehmsmeier and collaborators, we analyzed the minimum free energy between the miR148a/152 family and miR148aT as an estimation of the hybridization strength.21 Perfect pairing obtained with miR-148a:miR148aT had a free energy of −43.2 kcal/mol, whereas the imperfect base pairing of miR-148b:miR148aT and miR-152:miR148aT had a free energy of −37.3 kcal/mol and -32.8 kcal/mol, respectively. Interestingly, the minimum free energy of the family members imperfect pairing was superior to that of miR-148a with 27 validated endogenous target sites suggesting a stringent recognition (Figure 5b). Reporter assays of pLuc-miR148a148aT co-transfected with miRVEC-148b or miRVEC-152 in HeLa or MIA PaCa-2 cells showed reduced luciferase activity in the presence of either miRNA, experimentally proving the potential of miR-148b and miR-152 to bind to the 8 miR148aT target sites (Figure 5c).

Figure 5.

Target site recognition by miR-148 family members. (a) Scheme of sequence alignment of miR-148 family members (miR-148a, miR-148b, and miR-152) to miR-148a artificial target sites and its associated minimum free energy. Energies were calculated using RNAhybrid. (b) Minimum free energy and complementarity displayed in the miRNA:target sites hybridizations: miRT family members (recognition of artificial miR-148a target sites by miR-148a, miR-148b, and miR-152), validated seeds (recognition of 27 miR-148a experimentally validated target sites by miR-148a, miR-148b, and miR-152 or an unrelated miRNA), rand seq (recognition of 100 completely random sequences of 22 nucleotides by miR-148a), rand seq + fixed seed (recognition of 100 random sequences of 22 nucleotides with fixed miR-148 family seed region by miR-148a). (c) Luciferase activity in HeLa and MIA PaCa-2 cells cotransfected with the reporter plasmids pLuc-miR-148a148aT and miRNA expression vectors (p-miR-SC, p-miR-148a, miRVEC-148a, miRVEC-148b, and miRVEC-152). Dashed lines correspond to the values obtained with p-miR-SC. Values represent mean ± SEM of four independent experiments. *, **, and *** denote P < 0.05, P < 0.01, and P < 0.001, respectively.

Therefore, Ad-miR148a148aT detarget activity could be the result of miR-148/152 family member contribution.

Endogenous miRNAs and target genes remain unaffected by the presence of Ad-miR148aT, Ad-miR148a148aT, and Ad-miR148a216aT

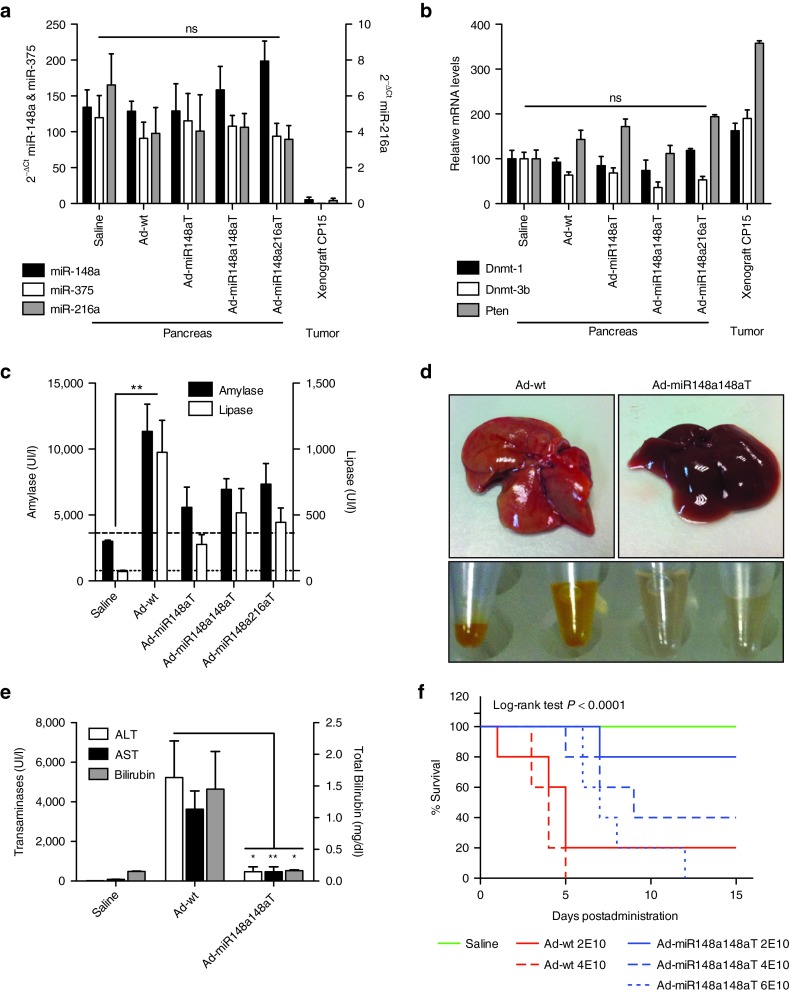

The decrease of the E1A mRNA levels in miR-148a and miR-216a-rich tissue could potentially associate with a depletion in the miR-148a or miR-216a content. Moreover, off-target effects on other pancreatic abundant miRNAs should be considered. We analyzed the content of miR-148a, miR-216a, and miR-375 in the pancreas of mice that received Ad-wt, Ad-miR148aT, Ad-miR148a148aT, and Ad-miR148a216aT, and compared to those of a control pancreas and a pancreatic xenograft. No differences in the levels of any of the three miRNAs were observed when compared to control mice, whereas a complete loss was obtained in the xenografts (Figure 6a). This proved that the content of the regulating miRNAs neither an unrelated miRNA were affected by infection with adenovirus bearing miR-148a nor miR-216a target sites.

Figure 6.

Improved safety profile of Ad-miR148aT, Ad-miR148a148aT, Ad-miR148a216aT. (a) miR-148a, miR-216a, and miR-375a expression in the pancreas of mice intraductally injected with the different viruses (n = 6/treatment). A saline group (n = 6) and a xenograft tumor (n = 6) were included as positive and negative controls respectively. ns denote no significant difference. (b) Expression of the validated targets for miR-148a (Dnmt-1, Dnmt-3b, Pten) and miR-216a (Pten) analyzed by RT-qPCR in the pancreas of mice intraductally injected with the different viruses as indicated above. (c) Assessment of pancreas toxicity. Determination of amylase and lipase in the serum of mice treated with Ad-wt, Ad-miR148aT, Ad-miR148a148aT, Ad-miR148a216aT for 3 days following intraductal administration of 2.1010vp/mice (n = 6). Data expressed as enzyme activity in international units (IU) per liter. Dashed lines correspond to the reference values for C57BL/6 mice. ** denote P < 0.01. (d) Representative macroscopic appearance of livers and blood serums (upper and lower panels) treated with Ad-wt and Ad-miR148a148aT. (e) Assesment of hepatotoxicity. Determination of AST, ALT, and total bilirubin in the serum of mice treated with Ad-wt and Ad-miR148a148aT for 3 days following intravenous administration of 2.1010vp/mice (n = 10). Data expressed as enzyme activity in international units (IU) per liter. * and ** denote P < 0.05 and P < 0.01, respectively. (f) Kaplan-Meier survival curves of mice treated with saline, Ad-wt and Ad-miR148a148aT at different doses (2.1010, 4.1010, and 6.1010 vp/mice) (n = 5/treatment). *** denote P < 0.001

The presence of E1A mRNA regulated by the miRNAs could lead to the sequestration of miR-148a or miR-216a away from their endogenous targets and interfere with their expression. Therefore, we selected for three validated targets in the literature: Dnmt-1, Dnmt-3b, and Pten all three targets of miR-148a and Pten also target of miR-216a22,23,24,25 and analyzed the mRNA content in the pancreas of mice infected with Ad-wt, Ad-miR148aT, Ad-miR148a148aT, and Ad-miR148a216aT, and compared to those of control animals and pancreatic xenografts. Consistent with previous reports showing tumor upregulation of these genes, an increase in the mRNA content was observed in the tumor xenografts.26,27,28 However, no significant changes in the mRNA abundance were detected in the pancreas of mice infected with any of the different viruses (Figure 6b). These data suggested that the regulation of Dnmt-1, Dnmt-3b, and Pten by miR-148a, and miR-216a was not altered despite they were actively suppressing E1A.

miR-148a and miR-216a-controlled adenoviruses reduce adenoviral-induced pancreatic and liver damage

The intravenous administration of high amounts of viral particles has been reported to induce liver damage.29 However, the impact of adenoviral intraductal delivery is unknown. Nevertheless the notorious pancreas transduction obtained by adenoviral administration through this route raises the issue of whether viral proteins can trigger any pancreatic damage. To assess whether the pancreas and liver detargeting effects of Ad-miRT adenoviruses translate into an amelioration in the toxicity profile of oncolytic adenoviruses several experiments were conducted. First, we investigated whether Ad-wt administration was causing any tissue damage and which were the effects of miR-148a and miR-216a-controlled adenoviruses. As an indication of pancreatic function, we assessed the levels of the pancreatic enzymes amylase and lipase in the serum of untreated and Ad-wt, Ad-miR148aT, Ad-miR148a148aT, and Ad-miR148a216aT-treated mice. A significant increase in both amylase and lipase was observed upon Ad-wt administration. In contrast, all three miRNA-controlled adenoviruses showed reduced levels of the pancreatic enzymes (Figure 6c). These data indicate that by diminishing the expression of E1A protein pancreatic damage could be attenuated.

To assess the impact of liver damage-associated toxicity following adenoviral intravascular delivery, Ad-wt and Ad-miR148a148aT were injected into immunocompetent mice at a viral dose of 2 × 1010 vp/mice. Three days after injection, we performed macroscopic observation of the liver and serum and the analysis of liver damage parameters. Livers from Ad-wt-injected mice showed a steatotic appearance that was not observed in Ad-miR148a148aT. Ad-wt triggered increased levels the aspartate aminotransferase (AST), alanine aminotransferase (ALT), and total bilirubin in the blood resulting in bright yellow sera (Figure 6d,e). However, mice injected with the same viral dose of Ad-miR148a148aT showed a 10-fold less induction in the different parameters (Figure 6e). In line with this ameliorated safety profile, mice survival at the injected dose showed only a 20% survival after 5 days in Ad-wt-injected mice, whereas all mice survived in Ad-miR148a148aT. At later time-points, one mouse from the Ad-miR148a148aT group died but the remaining animals, although suffered a reduction in body weight (Supplementary Figure S4), they underwent a complete recovery by day 15, suggesting no major liver damage. In a dose-scaling experiment, we observed that all mice were moribund in the group of Ad-wt injected with 4 × 1010 vp/mouse whereas 80% of mice were alive at 5 days in Ad-miR148a148aT-treated mice and by 15 days mice recovered from an initial decrease in body weight (Supplementary Figure S4). At the highest dose tested 6 × 1010 vp/mouse of Ad-miR148a148aT, all mice were alive for the first 5 days, but they did not survive at day 12 (Figure 6f).

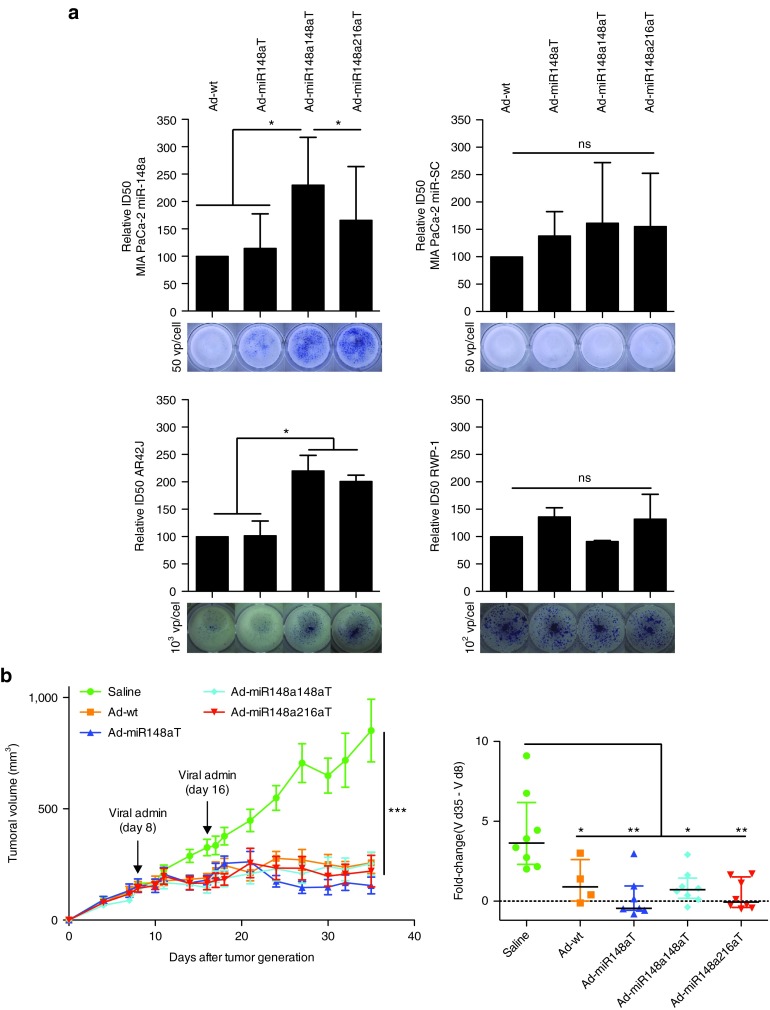

Ad-miR148aT, Ad-miR148a148aT, and Ad-miR148a216aT retain full lytic potency and induce an antitumor activity similar to Ad-wt

To evaluate whether Ad-miR148aT, Ad-miR148a148aT, and Ad-miR148a216aT oncolytic activity can be regulated by miR-148a and miR-216a cell viability assays were performed in cell lines expressing variable levels of the miRNAs, and the ID50 values were calculated. MIA PaCa-2-miR-148a cells infected with miRNA-controlled viruses showed less cytotoxicity than when infected with Ad-wt, however, no differences in cell viability were detected in MIA PaCa-2 miR-SC cells (Figure 7a). Furthermore, in miR-148a and miR-216a negative RWP-1 cells similar cytotoxicity was observed with all the viruses. Again a miRNA-dependent effect was observed in AR42J that expressed endogenous levels of both miRNAs. Cell viability was also reduced in Ad-miR148a148aT-infected cells expressing miR-148b or miR-152 when compared to Ad-wt (Supplementary Figure S5), further demonstrating the regulation of Ad-miR148a148aT by miR-148 family members. Next, we analyzed the antitumor efficacy of the different viruses in a xenograft model. Mice bearing MIA PaCa-2 subcutaneous tumors were treated intratumorally with two weekly doses of 2 × 1010 vp/mouse. Treatment with the different viruses produced a significant inhibition of tumor growth. In the control group, an increased volume from 3- to 10-fold was observed over a 27-day period, whereas in treated groups there was a strong delay in tumor progression and a regression in tumor volume was observed in some animals (Figure 7b). In agreement with the in vitro cytotoxicity miRNA-regulated viruses did not compromise their in vivo antitumor effects.

Figure 7.

Ad-miR148aT, Ad-miR148a148aT, and Ad-miR148a216aT show oncolytic potency in vitro and strong antitumoral activity in MIA PaCa-2 xenografts. (a) Cytotoxicity assays in the indicated cell lines. Half growth inhibitory concentration (IC50) was calculated for each cell line from dose–response curves. Mixed models were used for statistical analysis of dose-response curves. Data is shown as the mean ± SEM of four independent experiments. * and ns denote P < 0.05 and no significant difference, respectively. Representative cytotoxic effects at fixed viral doses were obtained by methylene blue staining (under each panel). (b) Follow-up of tumor volumes treated with Ad-miR148aT (n = 8), Ad-miR148a148aT (n = 8), Ad-miR148a216aT (n = 8), and Ad-wt (n = 4) at days 8 and 16 postcell inoculation. *** denote P < 0.001. Fold-change in tumor volume at day 35 in relation to the tumor volume at the time of the first viral administration. Fold-changes below 0, indicate tumor regression. * and ** denote P < 0.05 and P < 0.01, respectively.

Discussion

Curative surgery can only be applied to 10–20% of patients diagnosed with PDAC. Gene-viral experimental therapies are envisioned as potential treatments from which PDAC patients may benefit in the near future. For any molecular-engineered therapy, a tight control of transgene expression in the target tissue is fundamental to provide selectivity and confer increased safety to the treatment. We hypothesized that the pancreas- and liver-expressed miRNAs found to be downregulated in tumors could provide an efficient way, to sharply control transgene expression limiting the effect of the therapy to PDAC and minimizing nontumoral toxicity in the healthy pancreas and in the liver. In the present study, we have identified miR-148a and miR-216a as two miRNAs that can effectively repress transgene expression of miRNA-targeted adenoviruses regulating E1A. We show that miR-216a attenuates pancreas damage while miR-148a reduces both the pancreas and liver toxicity triggered by adenovirus. Importantly, all Ad-miRTs tested retain full antitumoral activity. Furthermore, miRNA regulation of adenoviruses did not perturb the expression or function of the corresponding endogenous miRNAs.

Consistent with previous studies, we identified miR-148a and miR-216a downregulated in PDAC and we demonstrate that both miR-148a and miR-216a efficiently and specifically downregulate transgene expression, when they are engineered with four closely spaced miRNA target sites. A higher magnitude of regulation could be achieved with miR-148a, which further increased when eight miRNA target sites were present. Similar suppression activity was observed with 8-miRTs when recognized only by miR-148a or by both miR-148a and miR-216a. These data validate miR-148a and miR-216a as pancreas cell regulators, and position them within the 40% of miRNAs with cellular activity. The enhanced regulation observed with miR-148a is supported by recent data indicating that only the most abundant miRNAs within a cell-mediated target suppression suggesting that the functional miRNome of a cell is considerably smaller that inferred from profiling studies.30 The suppression effect by Ad-miRTs was observed in vitro in a panel of cell lines, and the magnitude of the effect correlated with the specific miRNA cellular content. Importantly, in vivo, following intraductal delivery the repressive effect of E1A was observed both at the protein and at the mRNA level in accordance with miRTs designed to be perfectly complementary to the regulator miRNA. Such design has been demonstrated to allow the transcript to be degraded by an endonucleolytic cleavage mediated by Ago2 (ref. 8). However, our data also show that miRNA family members (as shown by miR-148/152) presenting a high degree of conservancy could contribute to viral detargeting. Under such circumstances, the bulge generated after pairing would probably trigger the transcriptional repression of the transgene rather than an endonucleolytic cleavage.

The presence of E1A transcripts with target sites recognizing miR-148a and miR-216a raised the issue of whether they could interfere with the balance between the levels of miRNAs and their total pool of targets mRNAs. The analysis of miRNA cellular concentration in mouse pancreas transduced with the different viruses revealed that miR-148a and miR-216a levels were not modified by the presence of any of the Ad-miRTs neither was the unrelated miR-375. These results are in line with data showing that miRNA regulation of a perfect target is a multiple-turnover process and miRNA-RISC complex is rapidly recycled.31 Despite not observing differences in miRNA concentration, still a competition for miRNA regulation between endogenous mRNA targets and E1A-miRT transcripts could take place. Expression analysis of Dnmt-1 and Dnmt-3b validated miR-148a targets, and Pten, a validated target of both miR-148a and miR-216a in Ad-miRT infected pancreas showed no variation in the mRNA of the endogenous targets when compared to control pancreas indicating that miRNA function was not saturated.

Reducing E1A gene expression in Ad-miRT-infected cells expressing miR-148a and miR-216a resulted in diminished Ad genome copy numbers. Reduced number of viral genomes was also observed in the mouse pancreas and liver, despite murine cells are low permissive to viral replication. These findings are consistent with authors that reported decreased viral replication in the liver with miR-122-controlled adenoviruses.9 The design with 8-miRTs showed a tighter adenoviral control than that of 4-miRT, although in the context of highly abundant miRNAs both Ad-8miRT and Ad-4miRT efficiently controlled E1A protein expression. In good agreement with the adenoviral control of Ad-miRT, minimal pancreatic and liver damage was observed when compared to Ad-wt, suggesting that in a therapeutic setting it might be possible to increase the injection dose, leading to superior therapeutic effects.

Nevertheless in tissues in which the expression of miR-148a and miR-216a was low, such were kidneys or intestine, Ad-miRT will escape from miRNA control. This raises the issue of potential toxicity in these organs. However, following an intravascular delivery, the liver is the predominant site of Ad5 sequestration, and the amount of viral particles that reaches the kidney or intestine is rather low. In this regard, in our study the amount of viral genomes detected in kidney was 60 times lower than in the liver. Interestingly, a preclinical study evaluating Ad5 viral biodistribution and toxicity in baboons detected 20- to 30-fold less viral genomes in the kidney than in the liver. Under this scenario, transaminases were increased whereas kidney function, assessed by serum creatinine was normal at all time points,32 suggesting that after intravascular delivery of adenoviruses kidney toxicity is of minor concern with respect to liver toxicity.

Importantly, and in agreement with miR-148a and miR-216a expression, Ad-miRTs exhibited similar anticancer activity in different pancreatic cancer models as compared with Ad-wt in vitro and in vivo, showing that Ad-miRT maintains a robust antitumor activity.

Taken together, this study shows that miR-148a and miR-216a are miRNAs with a high regulatory capacity in the pancreas, and miR-148a also in the liver, which allow achieving a relevant degree of specific regulation with a high saturation threshold not easily reached by vector transcripts. Based on their expression profile and their significant decrease in different PDAC stages, we demonstrate the suitability of these miRNAs to control Ad-miRT-engineered adenoviruses regulating E1A gene expression, providing oncolytic adenoviruses with enhanced safety and robust antitumoral efficacy against PDAC.

Materials and Methods

Patient samples. Pancreatic tumor or healthy tissues were obtained from patients diagnosed of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma in Hospital Clinic of Barcelona who underwent either endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspiration or surgical resection. All samples were snap frozen in liquid N2 and stored at –80 °C until further processing. All specimens were obtained according to the Institutional Review Board-approved procedures for consent. Informed consent was obtained from all subjects and all the experiments conformed to the principles set out in the WMA Declaration of Helsinki.

Cells lines and cell culture. The pancreatic cell lines 266-6, AR42J, BxPC-3, MIA PaCa-2, PANC-1, the hepatic cell line HepG2, HEK293, and HeLa were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC). NP-18, NP-31, and RWP-1 cells were derived from human pancreatic adenocarcinoma biopsies perpetuated as xenograft in nude mice.33,34 MIA PaCa-2 miR-148a and MIA PaCa-2 miR-SC cells were obtained in the laboratory by transfection of MIA PaCa-2 parental cells. For this purpose, the vector p-miR-148a and p-miR-SC were transfected to the MIA PaCa-2 cells and 24 hours later, the selection with puromycin started and miR-148a expressing clones were isolated.

Cells were maintained in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (266-6, BxPC-3, HeLa, MIA PaCa-2, PANC-1, RWP-1) or in RPMI 1640 medium (AR42J, NP-18, NP-31) (Gibco BRL), supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, penicillin (100 mg/ml) and streptomycin (100 mg/ml) (Gibco BRL).

Constructs. Oligonucleotide sequences of 118 pairs of bases (bp) having four fully complementary target sites for miR-148a or miR-216a and restriction sites for XbaI and HpaI were designed. These oligonucleotides (118-mer) were chemically synthesized, HPLC purified and purchased (Bonsaitech, Madrid, Spain). Sense miR-148a: 5′ CTAGAGTTAACACAAAGTTCTGTAGTGCACTGAATGCACAAAGTTCTGTAGTGCACTGATGCAACA AAGTTCTGTAGTGCACTGAGCATACAAAGTTCTGTAGTGCACTGAGTTAACT 3′; Sense miR-216a: 5′ CTAGAGTTAACTCACAGTTGCCAGCTGAGATTAATGCTCACAGTTGCCAGCTGAGATTAT GCATCACAGTTGCCAGCTGAGATTAGCATTCACAGTTGCCAGCTGAGATTAGTTAACT 3′. Sense and antisense oligonucleotides were annealed and cloned in the XbaI restriction site of the 3'UTR of pGL4.13 vector (Promega, Fitchburg, MA) to generate pLuc-miR148aT, pLuc-miR216aT. Both, pLuc-miR148aT and pLuc-miR216aT were used as templates to generate pLuc-miR148a148aT, and pLuc-miR148a216aT. To this end, XbaI and HpaI restriction sites were mutagenized (QuickChange Multi Site-Directed Mutagenesis kit, Stratagene, Wilmington, NC), and a new XbaI restriction site was introduced to facilitate further cloning of new miR-148a and miR-216a target sites.

Adenoviral plasmid shuttle pEndK35 encoding for the E1A gene was digested with HpaI (Fermentas, Pittsburgh, PA) to insert HpaI DNA fragments containing miR148aT, miR148a148aT, or miR148a216aT coming from pLuc-miR148aT, pLuc-miR148a148aT, or pLuc-miR148a216aT, respectively, to generate pEndK-miR148aT, pEndK-miR148a148aT, and pEndK-miR148a216aT. Previously, internal XbaI and HpaI restriction sites in pLuc-miR148a148aT, and pLuc-miR148a216aT were mutagenized to eliminate undesired restrictions.

Vectors expressing miR-148a and miR-216a were generated in retroviral vectors by cloning genomic region containing mature microRNA sequence (335 pb and 409 pb DNA fragments, respectively). Both microRNAs sequences were cloned by PCR in the HindIII restriction site of the pBabe-puro retroviral vector. Control vector expressing a scrambled microRNA (p-miR-SC) was generated from p-miR-148a by site-directed mutagenesis of the seven nucleotides in the microRNA seed region. Expression vectors miRVEC-148a, miRVEC-148b and miRVEC-152 were obtained from a microRNA library (Source Bioscience, Nottingham, UK).

Adenovirus generation. pAdeno-miRTs (pAdeno-miR148aT, pAdeno-miR148a148aT, and pAdeno-miR148a216aT) were generated by homologous recombination of the pEndK-miRTs (pEndK-miR148aT, pEndK-miR148a148aT, and pEndK-miR148a216aT) with the genome of the serotype 5 wild-type adenovirus (Ad-wt) in E. Coli BJ5183 cells (Stratagene) as described in ref. 17. The resulting pAdeno-miRTs were transfected to HEK293 cells and following several cycles of infection the viruses in A549 cells were purified by cesium chloride gradient to obtain Ad-miR148aT, Ad-miR148a148aT and Ad-miR148a216a. The Ad-wt adenovirus was obtained from the ATCC.

The concentration of physical viral particles (vp/ml) was determined by means of optical density analysis (OD260) and that of infectious particles (pfu/ml) by means of hexon immunostaining36 in HEK293 cells. All viruses presented the similar vp and pfu ratio.

Luciferase assays. Transient transfections were performed in cell lines, 24 hours after seeding in a 24 multiwell plate, with CalPhos Mammalian Transfection Kit (Clontech, Mountain View, CA) according to the manufacturer's protocol. pLuc-miRT and p-miR-148a or p-miR-216a plasmids were cotransfected with a Renilla luciferase vector to normalize for transfection efficiency Luciferase activity was measured 48 hours later using the Luciferase assay system (Promega).

Viral progeny production. Total cell lysates were obtained 3 days postinfection and progeny production was assessed by titration for hexon immunostaining in HEK293 cells.

In vitro cell survival studies. Dose–response curves were constructed for MIAPaCa-2 miR-148a, MIAPaCa-2 miR-SC and RWP-1. Cells were transduced with doses ranging from 0.001 vp/cell to 1,000 vp/cell of Ad-wt, Ad-miR148aT, Ad-miR148a148aT, or Ad-miR148a216aT. Cell viability was measured by a colorimetric assay (MTT Ultrapure, USB Corporation, Cleveland, OH) 3 days postinfection. Culture survival of cells infected at a unique dose was additionally assessed by methylene blue staining (Sigma, St Louis, MO).

Western blot analysis. Total protein extracts were obtained with lysis buffer (50 mmol/l Tris-HCl (pH 6.8), 2% SDS) containing 1% Complete Mini Protease Inhibitor (Roche Diagnostics GmbH, Basel, Switzerland). Lysates were centrifuged for 5 minutes at 14,000 rpm, and the cell debris was discarded. Protein concentration was determined by BCA Protein Assay Kit (Pierce-Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA) and 60 μg of total protein was resolved by electrophoresis on 10% gels and transferred to nitrocellulose membranes by standard methods. Membranes were immunoblotted with a rabbit anti-adenovirus-2/5 E1A polyclonal antibody (1:200; clone 13 S-5; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Dallas, TX) an overnight at 4 °C. Then the blots were rinsed with TBS-T and incubated for 1 hour at room temperature with either HRP-conjugated goat antirabbit IgG or rabbit antimouse IgG antibodies (DakoCytomation, Glostrup, Denmark). Antibody labeling was detected by the enhanced chemiluminescent method (Amersham Biosciences, Amersham, UK). Western blot expression data were normalized to Gapdh expression.

Quantitative miRNA RT-PCR. Total RNA was obtained from cell cultures or tissues using miRNeasy Mini RNA Extraction Kit (Qiagen, Venlo, The Netherlands). A total of 10 ng total RNA were reverse transcribed using a reverse transcriptase and stem-loop primers as indicated by the manufacturer (TaqMan MicroRNA Reverse Transcription Kit, Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). One and a half microliters of the reaction was used as a template for the qPCR amplification reaction (TaqMan Universal Master Mix, No AmpErase UNG, Applied Biosystems) in a thermocycler (ViiA 7 Real-Time PCR system, Applied Biosystems). Quantitative miRNA RT-PCR expression data were normalized to small nucleolar RNA U6 expression (RNU6B). Stem-loop primers and qPCR probes were purchased from TaqMan MicroRNA assay (Applied Biosystems): RNU6B (AB ID: 001093), hsa-miR-148a (AB ID: 000470), hsa-miR-216a (AB ID: 002220), hsa-miR-375 (AB ID: 000564).

cDNA synthesis and real-time quantitative PCR. RNA was obtained was isolated using miRNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen). A total of 1 µg was reverse transcribed using Moloney Murine Leukemia Virus reverse transcriptase and oligo(dT) (Ambion, Austin, TX). One microliter of the reaction was used as a template for the qPCR amplification reaction (LightCycler 480SYBER Green I Master Mix, Roche, Basel, Switzerland) in a thermocycler (ViiA 7 Real-Time PCR system, Applied Biosystems). E1A: Fw 5′-CGGCCATTTCTTCGGTAATA-3′, and Rev 5′-CCTCCGGTGATAATGACAAG-3′. Dnmt-1: Fw 5′-CGGACAGTGACACCCTTTCA-3′, and Rv 5′-TCCTGGTCTCTCTCCTCTGC-3′. Dnmt-3b: Fw 5′-GCCAGACCTTGGAAACCTCA-3′, and Rev 5′-CCTGTCATGTCCTGCGTGTA-3′. Pten: Fw 5′-GCGGAACTTGCAATCCTCAG-3′ and Rev 5′-AGGGTGAGTACAAGATACTCCT-3′. Quantitative RT-PCR expression data were normalized to Gdx: Fw 5′-GGCAGCTGATCTCCAAAGTCCTGG-3′, and Rev 5′-AACGTTCGATGTCATCCAGTGTTA-3′.

Viral genome quantification. DNA was obtained from frozen pancreas tissue by incubating in a buffer containing 0.1 mg/ml protease overnight at 55 °C. The pancreas adenoviral DNA content was determined with Real-Time PCR (100 ng of DNA) and SYBER Green I Master plus mix (Roche Diagnostics). Hexon primer sequences were as follows: forward 5′ GCCGCAGTGGTCTTACATGCACATC 3′ and reverse 5′CAGCACGCCGCGGATGTCAAAG 3′. The adenovirus copy number was quantified with a standard curve, consisting of adenovirus DNA dilutions (102–107 copies) in a background of genomic DNA. Samples and standards were amplified in triplicate, and the average number of total copies was normalized to copies per cell based on the input DNA weight amount and a genome size of 6 × 109 bp/cell. Results are expressed as relative viral genomes per cell.

Immunohistochemistry. Five-micrometer sections were deparaffinized, rehydrated, and treated with 10 mmol/l citrate buffer (pH 6.0) for antigen retrieval. Sections were then incubated overnight with a rabbit anti-adenovirus-2/5 E1A polyclonal antibody (1:200; clone 13 S-5; Santa Cruz Biotechnology). Bound antibodies were detected with Universal LSAB+ (DAKO Diagnostics, Glostrup, Denmark). Sections were counterstained with Mayer's hematoxylin. All sections were examined on a Leica DMR microscope (Leica, Wetzlard, Germany).

At least five independent, nonsequential, randomly selected pancreas sections were counted. A mean of 15 section areas of 358,800 μm2 were analyzed per treatment group with a 20× lens. A mean of 30 Langerhans Islets were analyzed per treatment group with a 20× lens. The total final surface area analyzed was similar for each of the different viral groups. The number of stained cells per squared micrometer was calculated according to the formula: (# E1A-positive cells/1,000 μm2 = # cells/# sections × S sections × 1,000). All the imaging analysis was assessed using ImageJ software (NIH, Bethesda, MD).

Pancreatic intraductal injection. Intraductal administration of adenovirus was performed as previously described in ref. 20. C57BL/6 mice (Charles River, Lyon, France) were injected with the corresponding virus or saline solution via the common bile duct in a final volume of 50 µl. At day 3, blood samples were obtained, mice were killed and different organs were collected and cryopreserved until their subsequent processing.

Toxicity analysis. Blood samples were collected by intracardiac puncture under anesthesia. Serum amylase, pancreatic lipase, AST, ALT, and total bilirubin were determined on an Olympus AU400 Analyzer (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan).

Mouse xenografts. MIA PaCa-2 cells (2.5 × 106), embedded in a matrix 1:1 of Matrigel (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA), were injected subcutaneously into each flank of male, 6–8 weeks old, BALB/c nude mice (Harlan, Sant Feliu de Codines, Spain). Tumors were measured at least three times a week, and their volume was calculated by the formula V = larger diameter × (smaller diameter)2 × pi ÷ 6. Viral treatment was initiated at day 8 postimplantation when tumors achieved a median volume of 160 mm3, 8 days later a second dose was administered. All animal procedures met the guidelines of European Community Directive 86/609/EEC, and approved by the local ethical committee.

Statistical analysis. The data are represented by the mean ± SEM, or population distribution with median and interquartile range (dot plot comparing grouped data). Statistical differences were evaluated using nonparametric, Mann–Whitney test; or using univariant general linear models with Tukey's b post hoc test. For all statistical analysis, the level of significance was set as P < 0.05. The software used for statistical analysis was IBM SPSS Statistics 20 (IBM, Armonk, NY); The data were represented using GraphPad Prism v5.0a (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA).

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL Figure S1. The number of microRNA binding sites for miR-216a and miR-148a determines the inhibition of transgene expression in reporter plasmids. Figure S2. Genome integrity of Ad-miRT viruses. Figure S3. Expression of miR-148 family members. Figure S4. Body weight follow-up of mice treated with Ad-wt and Ad-miR148a148aT. Figure S5. Oncolytic regulation by miR-148 family members.

Acknowledgments

We thank Anabel José and Maria Rovira-Rigau for technical support in the intraductal and intravenous adenoviral administration. We thank Eduardo Fernández-Rebollo and Marta Prades for technical help on pancreatic islets isolation. We are indebted to the Biobank core facility. This work was supported by grants from the Spanish Ministry of Economia y Competitividad BIO2011-30299-C02-01/02 and from Instituto de Salud Carlos III (ISCIII) PI13/02192, and receives partial support from the Generalitat de Catalunya SGR091527. CIBERER and CIBEREHD are initiatives of the ISCIII. CF group is partially financed by ISCIII (IIS10/00014) and cofinanced by Fondo Europeo de Desarrollo Regional (FEDER). X. Bofill-De Ros was recipient of a FPU fellowship from the Spanish Ministry of Education. This work was developed at the Centre Esther Koplowitz, Barcelona, Spain.

Supplementary Material

The number of microRNA binding sites for miR-216a and miR-148a determines the inhibition of transgene expression in reporter plasmids.

Genome integrity of Ad-miRT viruses.

Expression of miR-148 family members.

Body weight follow-up of mice treated with Ad-wt and Ad-miR148a148aT.

Oncolytic regulation by miR-148 family members.

References

- Khan S, Ansarullah, Kumar D, Jaggi M, Chauhan SC. Targeting microRNAs in pancreatic cancer: microplayers in the big game. Cancer Res. 2013;73:6541–6547. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-13-1288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sayed D, Abdellatif M. MicroRNAs in development and disease. Physiol Rev. 2011;91:827–887. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00006.2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bloomston M, Frankel WL, Petrocca F, Volinia S, Alder H, Hagan JP, et al. MicroRNA expression patterns to differentiate pancreatic adenocarcinoma from normal pancreas and chronic pancreatitis. JAMA. 2007;297:1901–1908. doi: 10.1001/jama.297.17.1901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cutts RJ, Gadaleta E, Hahn SA, Crnogorac-Jurcevic T, Lemoine NR, Chelala C. The pancreatic expression database: 2011 update. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011;39 Database issue:D1023–D1028. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee EJ, Gusev Y, Jiang J, Nuovo GJ, Lerner MR, Frankel WL, et al. Expression profiling identifies microRNA signature in pancreatic cancer. Int J Cancer. 2007;120:1046–1054. doi: 10.1002/ijc.22394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conroy T, Desseigne F, Ychou M, Bouché O, Guimbaud R, Bécouarn Y, et al. Groupe Tumeurs Digestives of Unicancer; PRODIGE Intergroup FOLFIRINOX versus gemcitabine for metastatic pancreatic cancer. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:1817–1825. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1011923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Von Hoff DD, Ervin T, Arena FP, Chiorean EG, Infante J, Moore M, et al. Increased survival in pancreatic cancer with nab-paclitaxel plus gemcitabine. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:1691–1703. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1304369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown BD, Gentner B, Cantore A, Colleoni S, Amendola M, Zingale A, et al. Endogenous microRNA can be broadly exploited to regulate transgene expression according to tissue, lineage and differentiation state. Nat Biotechnol. 2007;25:1457–1467. doi: 10.1038/nbt1372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cawood R, Chen HH, Carroll F, Bazan-Peregrino M, van Rooijen N, Seymour LW. Use of tissue-specific microRNA to control pathology of wild-type adenovirus without attenuation of its ability to kill cancer cells. PLoS Pathog. 2009;5:e1000440. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cawood R, Wong SL, Di Y, Baban DF, Seymour LW. MicroRNA controlled adenovirus mediates anti-cancer efficacy without affecting endogenous microRNA activity. PLoS One. 2011;6:e16152. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0016152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edge RE, Falls TJ, Brown CW, Lichty BD, Atkins H, Bell JC. A let-7 MicroRNA-sensitive vesicular stomatitis virus demonstrates tumor-specific replication. Mol Ther. 2008;16:1437–1443. doi: 10.1038/mt.2008.130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly EJ, Nace R, Barber GN, Russell SJ. Attenuation of vesicular stomatitis virus encephalitis through microRNA targeting. J Virol. 2010;84:1550–1562. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01788-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee CY, Rennie PS, Jia WW. MicroRNA regulation of oncolytic herpes simplex virus-1 for selective killing of prostate cancer cells. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15:5126–5135. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-0051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ylösmäki E, Lavilla-Alonso S, Jäämaa S, Vähä-Koskela M, af Hällström T, Hemminki A, et al. MicroRNA-mediated suppression of oncolytic adenovirus replication in human liver. PLoS One. 2013;8:e54506. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0054506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalyuzhniy O, Di Paolo NC, Silvestry M, Hofherr SE, Barry MA, Stewart PL, et al. Adenovirus serotype 5 hexon is critical for virus infection of hepatocytes in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:5483–5488. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0711757105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waddington SN, McVey JH, Bhella D, Parker AL, Barker K, Atoda H, et al. Adenovirus serotype 5 hexon mediates liver gene transfer. Cell. 2008;132:397–409. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.01.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huch M, Gros A, José A, González JR, Alemany R, Fillat C. Urokinase-type plasminogen activator receptor transcriptionally controlled adenoviruses eradicate pancreatic tumors and liver metastasis in mouse models. Neoplasia. 2009;11:518–28, 4 p following 528. doi: 10.1593/neo.81674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szafranska AE, Davison TS, John J, Cannon T, Sipos B, Maghnouj A, et al. MicroRNA expression alterations are linked to tumorigenesis and non-neoplastic processes in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Oncogene. 2007;26:4442–4452. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van de Bunt M, Gaulton KJ, Parts L, Moran I, Johnson PR, Lindgren CM, et al. The miRNA profile of human pancreatic islets and beta-cells and relationship to type 2 diabetes pathogenesis. PLoS One. 2013;8:e55272. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0055272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- José A, Sobrevals L, Miguel Camacho-Sánchez J, Huch M, Andreu N, Ayuso E, et al. Intraductal delivery of adenoviruses targets pancreatic tumors in transgenic Ela-myc mice and orthotopic xenografts. Oncotarget. 2013;4:94–105. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rehmsmeier M, Steffen P, Hochsmann M, Giegerich R. Fast and effective prediction of microRNA/target duplexes. RNA. 2004;10:1507–1517. doi: 10.1261/rna.5248604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braconi C, Huang N, Patel T. MicroRNA-dependent regulation of DNA methyltransferase-1 and tumor suppressor gene expression by interleukin-6 in human malignant cholangiocytes. Hepatology. 2010;51:881–890. doi: 10.1002/hep.23381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duursma AM, Kedde M, Schrier M, le Sage C, Agami R. miR-148 targets human DNMT3b protein coding region. RNA. 2008;14:872–877. doi: 10.1261/rna.972008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kato M, Putta S, Wang M, Yuan H, Lanting L, Nair I, et al. TGF-beta activates Akt kinase through a microRNA-dependent amplifying circuit targeting PTEN. Nat Cell Biol. 2009;11:881–889. doi: 10.1038/ncb1897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan K, Lian Z, Sun B, Clayton MM, Ng IO, Feitelson MA. Role of miR-148a in hepatitis B associated hepatocellular carcinoma. PLoS One. 2012;7:e35331. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0035331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill R, Calvopina JH, Kim C, Wang Y, Dawson DW, Donahue TR, et al. PTEN loss accelerates KrasG12D-induced pancreatic cancer development. Cancer Res. 2010;70:7114–7124. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-1649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng DF, Kanai Y, Sawada M, Ushijima S, Hiraoka N, Kosuge T, et al. Increased DNA methyltransferase 1 (DNMT1) protein expression in precancerous conditions and ductal carcinomas of the pancreas. Cancer Sci. 2005;96:403–408. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2005.00071.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang JJ, Zhu Y, Zhu Y, Wu JL, Liang WB, Zhu R, et al. Association of increased DNA methyltransferase expression with carcinogenesis and poor prognosis in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Clin Transl Oncol. 2012;14:116–124. doi: 10.1007/s12094-012-0770-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shayakhmetov DM, Gaggar A, Ni S, Li ZY, Lieber A. Adenovirus binding to blood factors results in liver cell infection and hepatotoxicity. J Virol. 2005;79:7478–7491. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.12.7478-7491.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mullokandov G, Baccarini A, Ruzo A, Jayaprakash AD, Tung N, Israelow B, et al. High-throughput assessment of microRNA activity and function using microRNA sensor and decoy libraries. Nat Methods. 2012;9:840–846. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hutvágner G, Zamore PD. A microRNA in a multiple-turnover RNAi enzyme complex. Science. 2002;297:2056–2060. doi: 10.1126/science.1073827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ni S, Bernt K, Gaggar A, Li ZY, Kiem HP, Lieber A. Evaluation of biodistribution and safety of adenovirus vectors containing group B fibers after intravenous injection into baboons. Hum Gene Ther. 2005;16:664–677. doi: 10.1089/hum.2005.16.664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dexter DL, Matook GM, Meitner PA, Bogaars HA, Jolly GA, Turner MD, et al. Establishment and characterization of two human pancreatic cancer cell lines tumorigenic in athymic mice. Cancer Res. 1982;42:2705–2714. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Villanueva A, García C, Paules AB, Vicente M, Megías M, Reyes G, et al. Disruption of the antiproliferative TGF-beta signaling pathways in human pancreatic cancer cells. Oncogene. 1998;17:1969–1978. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1202118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rojas JJ, Guedan S, Searle PF, Martinez-Quintanilla J, Gil-Hoyos R, Alcayaga-Miranda F, et al. Minimal RB-responsive E1A promoter modification to attain potency, selectivity, and transgene-arming capacity in oncolytic adenoviruses. Mol Ther. 2010;18:1960–1971. doi: 10.1038/mt.2010.173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cascante A, Abate-Daga D, Garcia-Rodríguez L, González JR, Alemany R, Fillat C. GCV modulates the antitumoural efficacy of a replicative adenovirus expressing the Tat8-TK as a late gene in a pancreatic tumour model. Gene Ther. 2007;14:1471–1480. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3303008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

The number of microRNA binding sites for miR-216a and miR-148a determines the inhibition of transgene expression in reporter plasmids.

Genome integrity of Ad-miRT viruses.

Expression of miR-148 family members.

Body weight follow-up of mice treated with Ad-wt and Ad-miR148a148aT.

Oncolytic regulation by miR-148 family members.