Abstract

Depression and low self-efficacy are both associated with worse glycemic control in adults with diabetes, but the relationship between these variables is poorly understood. We conducted a cross-sectional study examining associations between depressive symptoms, self-efficacy, and glycemic control among men (n = 64) and women (n = 98) with type 2 diabetes to see if self-efficacy mediates the relationship between depression and glycemic control. Correlational and mediational analyses examined the relationship between these three variables for the sample as a whole and separately by sex. A significant association between depressive symptoms and glycemic control was found for men (0.34, P < 0.01) but not for women (0.05, P = 0.59). Path analysis suggested that, among men, self-efficacy mediates the relationship between depressive symptoms and glycemic control. We conclude that men with depressive symptoms and type 2 diabetes may need tailored interventions that improve their self-efficacy in order to achieve glycemic control.

Keywords: Diabetes, Depression, Self-efficacy, Gender differences, Mediational model

Over 20 million adults in the United States have diabetes, and the CDC estimates that 1 in 3 Americans born today will develop diabetes in their lifetime (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention 2008; Narayan et al. 2003). Co-morbid depression affects 15–30% of all adults with diabetes, with women twice as likely to be affected as men (Anderson et al. 2001). Individuals with diabetes and co-morbid depression have more diabetes-related symptoms (Ciechanowski et al. 2003), worse glycemic control (Lustman et al. 2000), a higher prevalence of complications (Cohen et al. 1997; de Groot et al. 2001), reduced quality of life (Hanninen et al. 1999), and increased mortality (Katon et al. 2005; Zhang et al. 2005) compared to patients without depression.

While the pathway connecting depression and worse outcomes in persons with diabetes has yet to be fully elucidated, it likely includes both physiologic and behavioral factors (Musselman et al. 2003; Plante 2005). One important factor that may partially explain the relationship between depressive symptoms and worse diabetes related outcomes is patient self-efficacy. Self-efficacy is defined as the belief that one can successfully execute the behavior required to produce a given outcome (DeVellis and DeVellis 2001). Poor self-efficacy has been associated with both increased depressive symptoms as well as poor glycemic control, and could help to explain the connection between the two (Penninx et al. 1998; Sacco et al. 2005; Sousa et al. 2005; Talbot et al. 1997).

Self-efficacy is a key construct within Social Cognitive Theory (Bandura 1997), a theory that identifies multiple, interacting determinants of human behavior and behavior change. SCT has been applied to health behavior, and specifically of late, to self-management of chronic disease (Bandura 2004). Within this framework, self-efficacy is central to the self-regulatory behaviors that contribute to good self-management and disease control. In the case of diabetes, low self-efficacy has been associated with poor glycemic control (Sousa et al. 2005; Talbot et al. 1997; Wallston et al. 2007). Reduced adherence to self-care behaviors relevant for good diabetes self-management has been proposed as a mediator between the two (Kavanagh et al. 1993; Nakahara et al. 2006; Williams et al. 2004). This body of evidence has led some researchers to include a focus on improving individuals’ diabetes self-efficacy within behavioral interventions aimed at improving glycemic control and diabetes-related outcomes (Glasgow et al. 1995, 1989; Krichbaum et al. 2003).

Self-efficacy has also previously been linked with depression, both in theory and by direct observation (Bandura et al. 1999; Coultas et al. 2007; Penninx et al. 1998). DeVellis and DeVellis (2001) proposed that negative mood states such as depression could contribute to a poor sense of self-efficacy (DeVellis and DeVellis 2001). Multiple studies have identified an association between increased depressive symptoms and low self-efficacy in patients with diabetes (Chao et al. 2005; Sacco et al. 2007; Sacco et al. 2005; Talbot et al. 1997). In a study of 249 individuals with type 2 diabetes, Talbot et al. (1997) found that higher scores on the Beck Depression Inventory were associated with lower self-efficacy scores for several diabetes management behaviors (diet, exercise, and weight control) as measured by the self-efficacy subscale of the Multidimensional Diabetes Questionnaire. Using the same measure of self-efficacy in a study of 56 individuals with type 2 diabetes, Sacco et al. (2005) found that lower self-efficacy scores were associated with a higher number of depressive symptoms as measured by the Patient Health Questionnaire- 9 symptom depression checklist. Chao et al. (2005) went a step further in a study of 445 individuals with Type 2 diabetes, identifying an association between lower self-efficacy for medication adherence and higher depressive symptoms as measured by the PHQ-8 (a variant of the PHQ-9 that leaves off a question regarding suicidal ideation). Thus, to the extent that greater depressive symptoms are associated with low self-efficacy for a number of different diabetes related behaviors, and low self-efficacy is, in turn, associated with poor glycemic control, it is plausible that self-efficacy may play a mediating role in the relationship between depressive symptoms and glycemic control. However, to date, there has been little research examining this hypothesis. One study of 113 adults with diabetes that attempted to explore this relationship identified a significant association between glycemic control and self-efficacy for diabetes management, but because they did not find an independent association between glycemic control and depressive symptoms as measured by the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale they did not test for an association between self-efficacy and depressive symptoms (Ikeda et al. 2003).

The primary objective of the analyses presented in this article was to examine the relationship between depressive symptoms and glycemic control in patients with type 2 diabetes in a primary care setting and to assess whether self-efficacy plays a mediating role within that relationship. Because the relationship between depressive symptoms and glycemic control may vary by sex (Lloyd et al. 2000; Lustman et al. 2000; Pouwer and Snoek 2001) as might the determinants of self-efficacy (Buchanan and Selmon 2008), a secondary objective of the study was to examine whether these relationships were moderated by sex. We examined associations first among the total sample, then for men and women separately.

Methods

Participants

Study participants were part of a larger, cross-sectional study examining the role of health literacy and numeracy in diabetes and were enrolled from two primary care clinics, Vanderbilt University Medical Center and University of North Carolina School of Medicine (Cavanaugh et al. 2008; Huizinga et al. 2008). The study was approved by the Institutional Review Boards at both institutions, and written consent was obtained from all study participants.

Procedure

Patients were identified by clinic staff during routine clinic visits and referred for possible participation if they had a previous diagnosis of diabetes. Trained research assistants then assessed eligibility. Inclusion criteria were: a diagnosis of type 2 diabetes mellitus as determined by review of the medical chart; age 18 to 85 years; and the ability to speak English. Exclusion criteria were a previous diagnosis of significant dementia, psychosis, or blindness. In addition, the visual acuity of each participant was measured with a Rosenbaum Pocket Vision Screener at the time of enrollment and patients with corrected visual acuity of 20/50 or worse were excluded. Participants were enrolled from March 2004 until November 2005, and received $20 after completion of all survey measures.

Measures

Demographic and clinical information about patients’ diabetes was collected by patient interview and chart review. Glycosylated hemoglobin (HbA1c) is a measure of the glycemic control of diabetes patients during the previous 2–3 months (Jeffcoate 2004). The medical chart of the patient was reviewed by trained research staff and the most recent HbA1c was abstracted; 96% were obtained within 6-months of the subjects’ participation, and the mean time between HbA1c and evaluation was 43-days (median: 15-days). Health literacy was assessed using the previously validated Rapid Estimate of Adult Literacy in Medicine (Davis et al. 1991).

Depression was assessed using the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression (CES-D) Scale, a well-validated, 20-item, self-report instrument designed to measure depressive symptoms in the general population (Radloff 1977) that has also been used among patients with diabetes as a screening instrument (McHale et al. 2008). With a range from 0 to 60, most studies confirm that there is possible depression at a cut point of 16 or greater (Vahle et al. 2000). Perceived self-efficacy of diabetes self-management behaviors was assessed with the Perceived Diabetes Self-Management Scale (PDSMS). (Wallston et al. 2007) The PDSMS is a validated eight item instrument with good internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha = .83). Responses for each individual item range from 1 to 5, with total PDSMS scores ranging from 8 to 40, and higher scores indicating more confidence in managing one’s diabetes.

Data analysis

Analyses were performed using STATA, version 8.0 (College Park, TX, 2003). Descriptive statistics were used to assess baseline sample characteristics. Bivariate associations between sex and sample characteristics were assessed using independent samples t-tests and Pearson’s chi-square analyses. Analyses were repeated using Wilcoxon Rank-sum tests for variables with a non-normal distribution; however, the results were unchanged. We evaluated bivariate associations between self-efficacy and depressive symptoms using Pearson’s product-moment correlation–first for the total sample, then among men and women separately.

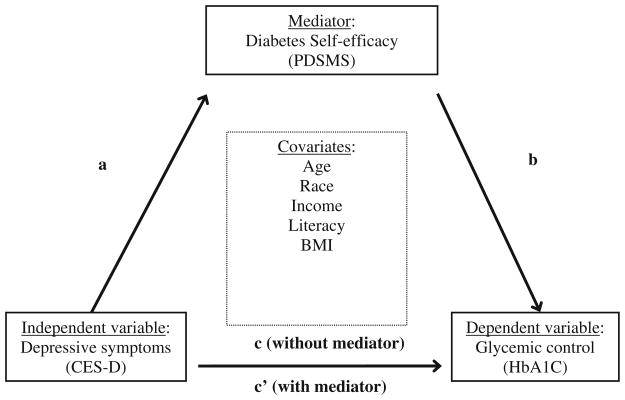

Associations between depressive symptoms, self-efficacy, and glycemic control (see Fig. 1) were examined using mediation analysis based on principles from Baron and Kenny (1986). Within this framework, a series of requirements must be met in order to establish that mediation has occurred: (1) the initial predictor variable is significantly correlated with the outcome (path c), thus establishing that there is an effect to be mediated; (2) the initial predictor variable is significantly associated with the proposed mediator (path a); (3) the mediator is significantly correlated with the outcome variable of interest (path b); and, critically, (4) the initial predictor variable no longer has an effect on the outcome of interest once the mediator is entered into the regression equation (path c′). The effects in steps 3 and 4 can be estimated in the same equation. In this study, we hypothesized that diabetes self-efficacy mediates the relationship between depressive symptoms and glycemic control. Thus, depressive symptoms (CES-D) served as the independent predictor variable, glycemic control (HbA1c) was the outcome variable, and self-efficacy (PDSMS) was the proposed mediator (see Fig. 1). We used multiple linear regression for the analyses; each model was adjusted for potential covariates selected a priori based on previously identified associations with the variables of interest; these included age, race, income, literacy level (raw REALM score), and body mass index (BMI) (Chapman et al. 2005; Fisher et al. 2001). All analyses were conducted first for the total sample and then, if appropriate, repeated for men and women separately.

Fig. 1.

Mediational model tested

For the first stage of the mediation analysis, the total effect (c) was obtained by regressing glycemic control (HbA1c) on the depressive symptoms (CES-D). Self-efficacy (PDSMS) was then regressed on depressive symptoms to assess the association between the independent variable and the mediator (path a). Finally, glycemic control was regressed on both depressive symptoms and self-efficacy to determine associations between self-efficacy and glycemic control (path b) as well as the “direct effects” (path c′) of depressive symptoms on glycemic control.

Results

Of the 162 participants, 60% were women and 54% were white (see Table 1); the mean age was 56 years. Half had an income of less than $20,000, and 62% had a 9th grade literacy level or higher. The mean HbA1c was 7.7 and 44% of the total sample had CES-D scores of 16 or greater, indicating possible depression. Men had higher income levels, higher levels of self-efficacy and lower levels of depressive symptoms than women.

Table 1.

Characteristics of total sample, men and women

| Characteristics | Percent or Mean (Standard deviation)

|

P value* | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total sample (N = 162) | Men (N = 64) | Women (N = 98) | ||

| Age, years (range 18–94) | 56 (11.48) | 55 (12.07) | 56 (11.14) | 0.94 |

| Race | 0.15 | |||

| White | 54 | 61 | 49 | |

| Black | 46 | 39 | 51 | |

| Education | 0.68 | |||

| More than college | 22 | 23 | 21 | |

| Some college | 23 | 25 | 23 | |

| High school or GED | 35 | 29 | 38 | |

| Less than high school | 20 | 23 | 18 | |

| Literacy | 0.13 | |||

| < 9th grade | 38 | 45 | 34 | |

| ≥9th grade | 62 | 55 | 66 | |

| Income | 0.01 | |||

| < $20,000 | 50 | 39 | 57 | |

| ≥$20,000 | 50 | 61 | 43 | |

| Insurance status | 0.03 | |||

| Uninsured | 2 | 5 | – | |

| Insured | 98 | 95 | 100 | |

| HbAlca (range 5–16) | 7.7 (1.95) | 7.6 (1.99) | 7.7 (1.93) | 0.82 |

| Duration of diabetes (range < 1–40 years) | 9.2 (7.97) | 9.6 (9.19) | 9.0 (7.09) | 0.65 |

| BMIa (kg/m2) (range 20–57) | 34.5 (7.65) | 33.3 (7.85) | 35.4 (7.44) | 0.09 |

| PDSMSa (range 8–40) | 28.4 (6.67) | 30.0 (5.89) | 27.4 (6.99) | 0.02 |

| CES-Da (range 0–60) | 15.8 (11.44) | 13.1 (11.87) | 17.5 (11.19) | 0.01 |

| < 16 | 56% | 62% | 51% | 0.15 |

| ≥16 | 44% | 38% | 49% | |

P-value is for differences between men and women

HbA1c Glycosylated hemoglobin, BMI body mass index, PDSMS perceived diabetes self-management scale, CES-D Center for Epidemiologic Studies—Depression scale

For the sample as a whole and especially for males, there was a significant correlation between depressive symptoms and diabetes self-efficacy, but the correlation for females was not statistically significant (see Table 2). Furthermore, for the sample as a whole and for the males, both depressive symptoms and self-efficacy were significantly correlated with glycemic control, but these correlations were not statistically significant for the females [although the relationship between self-efficacy and glycemic control (r = −0.18) approached significance for the females (P = .07)].

Table 2.

Unadjusted bivariate correlations (P-values) between diabetes self-efficacy (PDSMS), depressive symptoms (CES-D), and glycemic control (HbA1c) for the total sample and for men and women separately

| Total sample

|

Men

|

Women

|

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PDSMS | CES-D | A1C | PDSMS | CES-D | A1C | PDSMS | CES-D | A1C | |

| PDSMS | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||||

| CES-D | −0.25 (0.001) | 1.00 | −0.41 (< 001) | 1.00 | −0.12 (0.24) | 1.00 | |||

| HbA1c | −0.31 (0.001) | 0.17 (0.029) | 1.00 | −0.53 (< 001) | 0.34 (0.005) | 1.00 | −0.18 (0.07) | 0.05 (0.59) | 1.00 |

From the first stage of mediation analyses (path c), depressive symptoms were significantly associated with glycemic control for the total sample and for the men but not the women (see Table 2). For the second stage (path a), self-efficacy was significantly associated with depressive symptoms for the sample as a whole and for men but not for women (see Table 3). Because paths a and c were not significant for females, mediational analysis was not attempted for the female subsample. In the final stages (paths b and c′ in Fig. 1), self-efficacy was significantly associated with glycemic control for the total sample and for men, but the association between depressive symptoms and glycemic control was no longer significant once self-efficacy was entered into the model, suggesting complete mediation according to the Baron and Kenny criteria (see Table 4). Thus, for the males there is strong evidence that diabetes self-efficacy (as operationalized by the PDSMS) mediates the effect of depressive symptoms on glycemic control.

Table 3.

Standardized regression weights (P values) for diabetes self-efficacy (PDSMS) regressed on covariates and depressive symptoms (CES-D) among a sample of primary care patients with diabetes

| Characteristics | Total sample (N = 152) | Men only (N = 59) | Women only (N = 93) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | −002 (P = 0.98) | −01 (P = 0.92) | −004 (P = 0.97) |

| Race | |||

| Black | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| White | −.01 (P = 0.88) | .01 (P = 0.96) | −.06 (P = 0.60) |

| Income | |||

| < $20,000 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| ≥ $20,000 | −.12 (P = 0.19) | −.12 (P = 0.46) | −.19 (P = 0.12) |

| Literacy | |||

| < 9th grade | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| ≥ 9th grade | .15 (P = 0.10) | .13 (P = 0.41) | .23 (P = 0.07) |

| BMI | −.11 (P = 0.19) | −.08 (P = 0.55) | −.09 (P = 0.38) |

| Depressive symptoms | −.23 (P = 0.07) | −.40 (P < 0.01) | −.09 (P = 0.36) |

Table 4.

Standardized regression weights (P values) for glycemic control (HbA1c) regressed on covariates and depressive symptoms (CES-D), with the addition of diabetes self-efficacy (PDSMS) in the meditational model

| Total sample (N = 1530 | Total sample Mediation model | Men only (N = 59) | Men only Mediation model | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | −.24 (P < 0.01) | −.24 (P < 0.01) | −.15 (P = 0.26) | −.16 (P = 0.19) |

| Race | ||||

| Black | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| White | −.09 (P = 0.29) | −.09 (P = 0.26) | −.17 (P = 0.21) | −.16 (P = 0.17) |

| Income | ||||

| < $20,000 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| ≥ $20,000 | .22 (P = 0.01) | .19 (P = 0.03) | .38 (P = 0.01) | .33 (P = 0.01) |

| Literacy | ||||

| < 9th grade | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| ≥ 9th grade | −.05 (P = 0.54) | −.02 (P = 0.85) | −.19 (P = 0.21) | −.13 (P = 0.32) |

| BMI | −.03 (P = 0.67) | −.06 (0.44) | .16 (P = 0.19) | .13 (P = 0.25) |

| CESD | .17 (P = 0.04) | .11 (P = 0.18) | .40 (P <0.01) | .20 (P = 0.09) |

| PDSMS | – | −.25 (P < 0.01) | – | −.41 (P < 0.01) |

Discussion

This study assessed the association between depression, self efficacy and glycemic control among 162 men and women with type 2 diabetes receiving care in a primary care setting. The proportion of patients with possible depression (CESD score>16), found in the present study was 44% among the total sample, 38% among men and 49% among women, numbers similar to those identified in previous studies of patients with diabetes.(Anderson et al. 2001) A significant association between depressive symptoms and glycemic control was identified for men but not for women. Mediation analysis suggests that, among men, diabetes self-efficacy mediates the relationship between depressive symptoms and glycemic control.

In this study, increased depressive symptoms were associated with worse glycemic control among men but not among women. While the association between depressive symptoms and glycemic control has been demonstrated previously, only a handful of studies have examined this association by sex (Adriaanse et al. 2006; Lloyd et al. 2000; Pouwer and Snoek 2001). In a study of just over 100 clinic patients, Lloyd et al. (2000) also found a correlation between depression and glycemic control among men but not women. They postulated that the difference may be due to differences in coping techniques between men and women or, alternatively, by other unmeasured variables. In contrast to the findings in that study and in ours, Pouwer and Snoek (2001) identified a significant association between depression and glycemic control among women but not men in multivariate analyses of data from several hundred patients with type 2 diabetes (Pouwer and Snoek 2001). Those authors hypothesize that estrogen levels may play a mediating role in the relationship between glycemic control and depression. A separate study in the Netherlands found a weak association between depressive symptoms and insulin resistance, with no differences in this association by sex (Adriaanse et al. 2006). Differences between the samples and selection of measures as well as covariates may have contributed to the differences between these findings. The results of our current study support the findings of Lloyd et al. yet conflict with those of Pouwer et al. and underscore the need for larger, prospective studies examining the relationship of depression and glycemic control by sex in order to move towards consensus.

Similarly, more research is needed to identify the mechanisms by which depression and glycemic control may be linked (Lustman et al. 2005). To our knowledge, ours is the first study to demonstrate that, at least among men, self-efficacy plays a mediating role between depressive symptoms and poor glycemic control. Our findings support the DeVellis’s hypothesis that negative mood states such as depression contribute to a poor sense of self-efficacy (DeVellis and DeVellis 2001), in turn leading to poor health outcomes. The findings are also consistent with previous evidence supporting a connection between mental health and health outcomes among men, such as the study by Schnall et al. (1994) that identified an association between work stress and increased coronary heart disease among men but not women. However, why an association between depressive symptoms, self-efficacy and glycemic control was identified among men but not women in our sample remains unclear. Though the data in the current study do not allow further examination of why this may be the case, we propose two hypotheses for future consideration.

Causal pathways between psychosocial constructs and health outcomes sometimes differ between men and women (Pilote et al. 2007; Wang et al. 2005). In this case, it is possible that depression manifests differently in men with diabetes than in women, with depressive symptoms more intricately tied to confidence and feelings of mastery for men. While we could find no studies directly testing this hypothesis, there is evidence that men and women differ in other diabetes related cognitive and social factors. For example, in a study of 249 patients with type 2 diabetes, Talbot et al. (1997) found that men reported higher levels of social support as well as higher levels of positive reinforcing behaviors than women, both factors that could contribute to lower rates of depression among men with diabetes. Thus, it could be that depressive symptoms are simply more damaging to men’s perceived confidence when it comes to diabetes management.

An alternative explanation is that while general self-efficacy for diabetes management was not associated with depressive symptoms among women in this study, perhaps self-efficacy for other specific diabetes-related behaviors would have been evident had those questions been asked, for example self-efficacy for diet or self-efficacy for physical activity. This would be more congruent with previous studies suggesting that sex differences in self-esteem and self-efficacy may partially account for the emergence of sex differences in depression and anxiety as early as adolescence (McCauley Ohannessian et al. 1999). In order to test these hypotheses, future prospective studies assessing the relationship between depressive symptoms and self-efficacy should include analyses stratified by sex as well as multiple measures of self-efficacy in order to better elucidate the causal pathways involved for each group (Wiginton 2006).

Limitations

Several limitations may moderate the interpretation of our findings. As a cross-sectional study we are able to identify associations, but cannot attribute causality. Our relatively small sample size, especially when separated by sex, may have limited our ability to identify certain associations. Also, while the proportion of patients reporting depressive symptoms is fairly representative of an average diabetes clinic population (Anderson et al. 2001), the sample as a whole (and particularly among men) generally reported mild depressive symptoms on the CES-D, and only a moderate portion of patients (n = 71) met CES-D criteria for mild depression (CESD score>16), and a small portion met criteria for moderate depression (CESD score >26). The main analyses lost significance when conducted only among those who had CESD scores >16, although the small sample size and constricted variance likely limited these analyses. Thus, the significant relationships between self-efficacy, depressive symptoms, and glycemic control identified in the current study should be interpreted with caution when applied to a population with greater depressive symptoms. Also, because this study was conducted at two academically-affiliated primary care centers in the Southeast US and included a convenience sample of primarily White and African American patients, our findings may or may not be generalizable to other settings or patient populations. Finally, glycemic control (HbA1c) was not measured at the same time the questionnaires were completed and may not accurately reflect ongoing levels of control; similarly, depressive symptoms were only assessed over the previous seven days (the time frame of the CES-D) and may not represent true levels of depression as symptoms may wax or wane over time.

Implications

This study identified a significant association between depressive symptoms and glycemic control for men but not for women, further adding to a growing body of literature suggesting that the linkage between depression and glycemic control may be unstable across sex. That self-efficacy may play a mediating role between depressive symptoms and glycemic control among men suggests that efforts to improve diabetes outcomes among individuals with higher depressive symptoms may need to target men and women differently. Women and men have been observed to have differing responses to interventions targeting mental health in the context of chronic disease (Naqvi et al. 2005). Men with depressive symptoms and type 2 diabetes may need specific self-management enhancing interventions that improve their self-efficacy in order to achieve glycemic control. In summary, much is still not known about the underlying mechanisms between depression and diabetes, particularly those that may be distinct to men and to women (Lustman et al. 2005). Future, prospective studies should further explore potential factors on the causal pathways between depression and poor diabetes control for both men and women to facilitate the development of tailored interventions towards a goal of improving diabetes-related health outcomes (Legato et al. 2006).

Acknowledgments

This research is funded with support from the American Diabetes Association (Novo Nordisk Clinical Research Award), the Pfizer Clear Health Communication Initiative, and the Vanderbilt Diabetes Research & Training Center (NIDDK 5P60DK020593). Dr. Rothman is also currently supported by an NIDDK Career Development Award (NIDDK 5K23DK065294) and Dr Cherrington by the Robert Wood Johnson Physician Faculty Scholars’ Program [047948].

Contributor Information

Andrea Cherrington, Email: cherrington@uab.edu, Department of Medicine, Division of General Internal Medicine, University of Alabama School of Medicine, 725 Faculty Office Tower, 1530 3rd Avenue South, Birmingham, AL 35294-3407, UK.

Kenneth A. Wallston, Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville, TN, USA

Russell L. Rothman, Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville, TN, USA

References

- Adriaanse MC, Dekker JM, Nijpels G, Heine RJ, Snoek FJ, Pouwer F. Associations between depressive symptoms and insulin resistance: the hoorn study. Diabetologia. 2006;49(12):2874–2877. doi: 10.1007/s00125-006-0500-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson RJ, Freedland KE, Clouse RE, Lustman PJ. The prevalence of comorbid depression in adults with diabetes: a meta-analysis. Diabetes Care. 2001;24(6):1069–1078. doi: 10.2337/diacare.24.6.1069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bandura A, editor. Self-efficacy: the exercise of control. New York: Freeman; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Bandura A. Health promotion by social cognitive means. Health Education and Behavior. 2004;31(2):143–164. doi: 10.1177/1090198104263660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bandura A, Pastorelli C, Barbaranelli C, Caprara GV. Self-efficacy pathways to childhood depression. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1999;76(2):258–269. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.76.2.258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buchanan T, Selmon N. Race and gender differences in self-efficacy: assessing the role of gender role attitudes and family background. Sex Roles. 2008;58:822–836. [Google Scholar]

- Cavanaugh K, Huizinga MM, Wallston KA, Gebretsadik T, Shintani A, Davis D, et al. Association of numeracy and diabetes control. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2008;148(10):737–746. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-148-10-200805200-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control, Prevention. National diabetes fact sheet: general information and national estimates on diabetes in the United States, 2007. Atlanta, GA: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Chao J, Nau DP, Aikens JE, Taylor SD. The mediating role of health beliefs in the relationship between depressive symptoms and medication adherence in persons with diabetes. Research in Social and Administrative Pharmacy. 2005;1(4):508–525. doi: 10.1016/j.sapharm.2005.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chapman DP, Perry GS, Strine TW. The vital link between chronic disease and depressive disorders. Preventing Chronic Disease. 2005;2(1):A14. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ciechanowski PS, Katon WJ, Russo JE, Hirsch IB. The relationship of depressive symptoms to symptom reporting, self-care and glucose control in diabetes. General Hospital Psychiatry. 2003;25(4):246–252. doi: 10.1016/s0163-8343(03)00055-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen ST, Welch G, Jacobson AM, De Groot M, Samson J. The association of lifetime psychiatric illness and increased retinopathy in patients with type I diabetes mellitus. Psychosomatics. 1997;38(2):98–108. doi: 10.1016/S0033-3182(97)71477-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coultas DB, Edwards DW, Barnett B, Wludyka P. Predictors of depressive symptoms in patients with COPD and health impact. Copd. 2007;4(1):23–28. doi: 10.1080/15412550601169190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis TC, Crouch MA, Long SW, Jackson RH, Bates P, George RB, et al. Rapid assessment of literacy levels of adult primary care patients. Family Medicine. 1991;23(6):433–435. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Groot M, Anderson R, Freedland KE, Clouse RE, Lustman PJ. Association of depression and diabetes complications: a meta-analysis. Psychosomatic Medicine. 2001;63(4):619–630. doi: 10.1097/00006842-200107000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeVellis B, DeVellis R. Self-efficacy and health. In: Baum A, Revenson T, Singh J, editors. Handbook of Health Psychology. 2001. pp. 235–247. [Google Scholar]

- Fisher L, Chesla CA, Mullan JT, Skaff MM, Kanter RA. Contributors to depression in Latino and European-American patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2001;24(10):1751–1757. doi: 10.2337/diacare.24.10.1751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glasgow RE, Toobert DJ, Riddle M, Donnelly J, Mitchell DL, Calder D. Diabetes-specific social learning variables and self-care behaviors among persons with type II diabetes. Health Psychology. 1989;8(3):285–303. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.8.3.285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glasgow RE, Toobert DJ, Hampson SE, Wilson W. Behavioral research on diabetes at the oregon research institute. Annals of Behavioral Medicine. 1995;17:32–40. doi: 10.1007/BF02888805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanninen JA, Takala JK, Keinanen-Kiukaanniemi SM. Depression in subjects with type 2 diabetes. Predictive factors and relation to quality of life. Diabetes Care. 1999;22(6):997–998. doi: 10.2337/diacare.22.6.997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huizinga MM, Elasy TA, Wallston KA, Cavanaugh K, Davis D, Gregory RP, et al. Development and validation of the diabetes numeracy test (DNT) BMC Health Services Research. 2008;8:96. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-8-96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ikeda K, Aoki H, Saito K, Muramatsu Y, Suzuki T. Associations of blood glucose control with self-efficacy and rated anxiety/depression in type II diabetes mellitus patients. Psychological Reports. 2003;92(2):540–544. doi: 10.2466/pr0.2003.92.2.540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeffcoate SL. Diabetes control and complications: the role of glycated haemoglobin, 25 years on. Diabetic Medicine. 2004;21(7):657–665. doi: 10.1046/j.1464-5491.2003.01065.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katon WJ, Rutter C, Simon G, Lin EH, Ludman E, Ciechanowski P, et al. The association of comorbid depression with mortality in patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2005;28(11):2668–2672. doi: 10.2337/diacare.28.11.2668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kavanagh DJ, Gooley S, Wilson PH. Prediction of adherence and control in diabetes. Journal of Behavioral Medicine. 1993;16(5):509–522. doi: 10.1007/BF00844820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krichbaum K, Aarestad V, Buethe M. Exploring the connection between self-efficacy and effective diabetes self-management. The Diabetes Educator. 2003;29(4):653–662. doi: 10.1177/014572170302900411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Legato MJ, Gelzer A, Goland R, Ebner SA, Rajan S, Villagra V, et al. Gender-specific care of the patient with diabetes: review and recommendations. Gender Medicine. 2006;3(2):131–158. doi: 10.1016/s1550-8579(06)80202-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lloyd CE, Dyer PH, Barnett AH. Prevalence of symptoms of depression and anxiety in a diabetes clinic population. Diabetic Medicine. 2000;17(3):198–202. doi: 10.1046/j.1464-5491.2000.00260.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lustman PJ, Anderson RJ, Freedland KE, de Groot M, Carney RM, Clouse RE. Depression and poor glycemic control: a meta-analytic review of the literature. Diabetes Care. 2000;23(7):934–942. doi: 10.2337/diacare.23.7.934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lustman PJ, Clouse RE, Ciechanowski PS, Hirsch IB, Freedland KE. Depression-related hyperglycemia in type 1 diabetes: a mediational approach. Psychosomatic Medicine. 2005;67(2):195–199. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000155670.88919.ad. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCauley Ohannessian C, Lerner RM, Lerner JV, von Eye A. Does self-competence predict gender differences in adolescent depression and anxiety? Journal of Adolescence. 1999;22(3):397–411. doi: 10.1006/jado.1999.0231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McHale M, Hendrikz J, Dann F, Kenardy J. Screening for depression in patients with diabetes mellitus. Psychosomatic Medicine. 2008;70(8):869–874. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e318186dea9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Musselman DL, Betan E, Larsen H, Phillips LS. Relationship of depression to diabetes types 1 and 2: epidemiology, biology, and treatment. Biological Psychiatry. 2003;54(3):317–329. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(03)00569-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakahara R, Yoshiuchi K, Kumano H, Hara Y, Suematsu H, Kuboki T. Prospective study on influence of psychosocial factors on glycemic control in Japanese patients with type 2 diabetes. Psychosomatics. 2006;47(3):240–246. doi: 10.1176/appi.psy.47.3.240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naqvi TZ, Naqvi SS, Merz CN. Gender differences in the link between depression and cardiovascular disease. Psychosomatic Medicine. 2005;67(1):S15–S18. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000164013.55453.05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Narayan KM, Boyle JP, Thompson TJ, Sorensen SW, Williamson DF. Lifetime risk for diabetes mellitus in the United States. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2003;290(14):1884–1890. doi: 10.1001/jama.290.14.1884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Penninx BW, van Tilburg T, Boeke AJ, Deeg DJ, Kriegsman DM, van Eijk JT. Effects of social support and personal coping resources on depressive symptoms: different for various chronic diseases? Health Psychology. 1998;17(6):551–558. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.17.6.551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pilote L, Dasgupta K, Guru V, Humphries KH, McGrath J, Norris C, et al. A comprehensive view of sex-specific issues related to cardiovascular disease. Canadian Medical Association Journal. 2007;176(6):S1–S44. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.051455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plante GE. Depression and cardiovascular disease: a reciprocal relationship. Metabolism. 2005;54(5 Suppl 1):45–48. doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2005.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pouwer F, Snoek FJ. Association between symptoms of depression and glycaemic control may be unstable across gender. Diabetic Medicine. 2001;18(7):595–598. doi: 10.1046/j.1464-5491.2001.00499.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radloff L. The CES-D scale: a self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychology Measurements. 1977;3:385–401. [Google Scholar]

- Sacco WP, Wells KJ, Vaughan CA, Friedman A, Perez S, Matthew R. Depression in adults with type 2 diabetes: the role of adherence, body mass index, and self-efficacy. Health Psychology. 2005;24(6):630–634. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.24.6.630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sacco WP, Wells KJ, Friedman A, Matthew R, Perez S, Vaughan CA. Adherence, body mass index, and depression in adults with type 2 diabetes: the mediational role of diabetes symptoms and self-efficacy. Health Psychology. 2007;26(6):693–700. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.26.6.693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schnall PL, Landsbergis PA, Baker D. Job strain and cardiovascular disease. Annual Review of Public Health. 1994;15:381–411. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pu.15.050194.002121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sousa VD, Zauszniewski JA, Musil CM, Price Lea PJ, Davis SA. Relationships among self-care agency, self-efficacy, self-care, and glycemic control. Research and Theory for Nursing Practice. 2005;19(3):217–230. doi: 10.1891/rtnp.2005.19.3.217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Talbot F, Nouwen A, Gingras J, Gosselin M, Audet J. The assessment of diabetes-related cognitive and social factors: the Multidimensional Diabetes Questionnaire. Journal of Behavioral Medicine. 1997;20(3):291–312. doi: 10.1023/a:1025508928696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vahle VJ, Andresen EM, Hagglund KJ. Depression measures in outcomes research. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation. 2000;81(12 Suppl 2):S53–S62. doi: 10.1053/apmr.2000.20625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallston K, Rothman R, Cherrington A. Psychometric properties of the perceived diabetes self-management scale (PDSMS) Journal of Behavioral Medicine. 2007;30(5):395–401. doi: 10.1007/s10865-007-9110-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang N, Iwasaki M, Otani T, Hayashi R, Miyazaki H, Xiao L, et al. Perceived health as related to income, socioeconomic status, lifestyle, and social support factors in a middle-aged Japanese. Journal of Epidemiology. 2005;15(5):155–162. doi: 10.2188/jea.15.155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiginton KL. Advancing on the discussion of gender-specific health determinants. Health Education and Behavior. 2006;33(6):744–746. doi: 10.1177/1090198106288044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams GC, McGregor HA, Zeldman A, Freedman ZR, Deci EL. Testing a self-determination theory process model for promoting glycemic control through diabetes self-management. Health Psychology. 2004;23(1):58–66. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.23.1.58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X, Norris SL, Gregg EW, Cheng YJ, Beckles G, Kahn HS. Depressive symptoms and mortality among persons with and without diabetes. American Journal of Epidemiology. 2005;161(7):652–660. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwi089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]