Abstract

Aim

Very low birth weight (VLBW) infants have difficulty transitioning to independent oral feeding, be they breast- or bottle-feeding. We developed a ‘self-paced’ feeding system that eliminates the natural presence of the positive hydrostatic pressure and internal vacuum build-up within a bottle during feeding. Such system enhanced these infants’ oral feeding performance as monitored by overall transfer (OT; % ml taken/ml prescribed), rate of transfer (RT; ml/min over an entire feeding). This study hypothesizes that the improvements observed in these infants resulted from their ability to use more mature oral feeding skills (OFS).

Methods

‘Feeders and growers’ born between 26–29 weeks gestation were assigned to a control or experimental group fed with a standard or self-paced bottle, respectively. They were monitored when taking 1–2 and 6–8 oral feedings/day. OFS was monitored using our recently published non-invasive assessment scale that identifies 4 maturity levels based on infants’ RT and proficiency (PRO; % ml taken during the first 5 min of a feeding/total ml prescribed) during bottle feeding.

Results

Infants oral feeding outcomes, i.e., OT, RT, PRO, and OFS maturity levels were enhanced in infants fed with the self-paced vs. standard bottle (p ≤ 0.007).

Conclusion

The improved oral feeding performance of VLBW infants correlated with enhanced OFS. This study is a first to recognize that VLBW infants’ true OFS are more mature than recognized. We speculate that the physical properties inherent to standard bottles that are eliminated with the self-paced system interfere with the display of their true oral feeding potential thereby hindering their overall oral feeding performance.

Keywords: newborn, prematurity, bottle feeding

Background

Infants born prematurely are at high risk of encountering difficulty feeding by mouth. Insofar as attainment of independent oral feeding is an important factor predictive of hospital length of stay1, any tool or therapy that can enhance preterm infants’ oral feeding skills not only ensures safe and successful oral feeding, but also shortens their hospitalization, hastens mother-infant reunion, and decreases medical cost.

In an earlier study, we compared the oral feeding performance of very low birth weight (VLBW) infants (26 to 29 weeks gestation) who were offered in two consecutive feeding, in a random order, a standard (STD) bottle and a “self-paced” (SP) feeding system2. Enhanced overall transfer (OT; % volume taken/volume prescribed) and rate of transfer (RT, ml/min over an entire feeding) were consistently observed when the subjects fed with the SP system2,3. Additionally, these infants used more mature sucking patterns than their STD counterparts, 3. No adverse events occurred that did not self-resolve, e.g., oxygen desaturation, bradycardia, and/or apnea3.

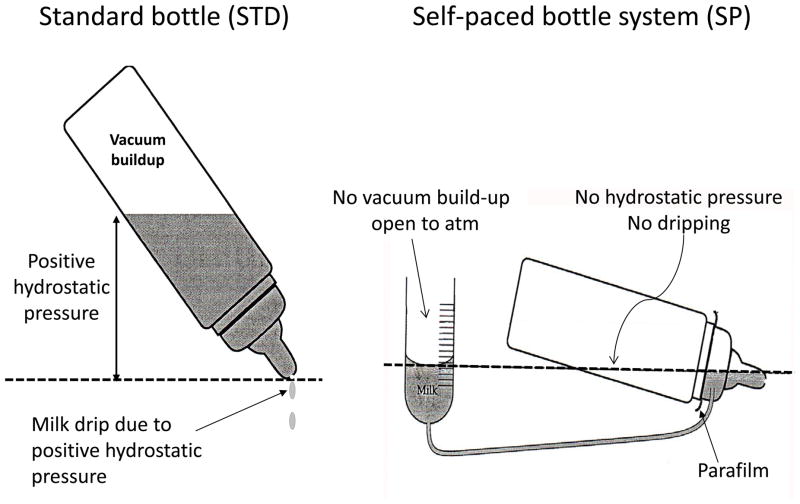

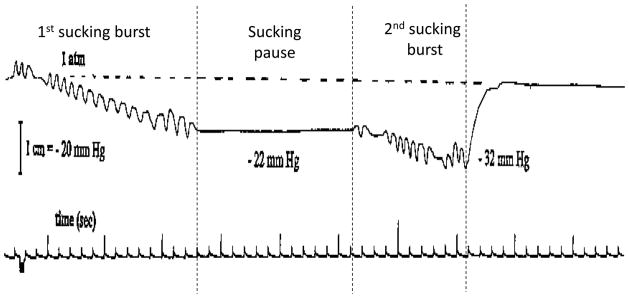

Briefly, the properties of the SP feeding system consist of the continuous elimination of the hydrostatic pressure normally present when a bottle is tilted and of the vacuum build-up as the container empties during a feeding (Figs. 1, 2). Two benefits ensue from this technique. First, the absence of milk drip gives infants control over their own feeding as milk only flows when they are actively sucking; the absence of milk drip allowing them to pause/rest/breathe whenever needed. Second, in the absence of any internal vacuum build-up which naturally holds back milk outflow and occurs when a STD bottle is used (Fig 2) 2, infants are more efficient as their sucking effort does not have to overcome such resistance prior to obtaining milk. Thus, infants can regulate milk flow as a function of the maturity level of their oral feeding skills and/or limitations and be more efficient as their sucking effort is solely spent on feeding.

Figure 1.

Differing physical properties between a standard (STD) and self-paced (SP) feeding tool

Figure 2.

Tracing of an internal vacuum build-up within a STD bottle during a feeding from a VLBW infant taking 8 oral feedings per day

In a subsequent study, we developed a non-invasive scale to monitor infantsoral feeding skills (OFS) 4. This scale is divided into 4 levels and allows for the differentiation of infants’ true nutritive sucking skills and fatigue (or lack of endurance) during oral feeding (details below). Based on the information compiled from the above work, the present study aimed at determining whether the enhanced oral feeding performance of infants feeding with a SP vs. STD bottle corresponded to more mature OFS. It was hypothesized that the improved oral feeding performance observed in infants fed with the SP system would result from the ability to employ more mature OFS in the absence of both hydrostatic pressure and internal vacuum build-up normally present in STD bottles.

Study Design/Methods

Subjects

A convenience sample of 30 infants born between 26 and 29 weeks gestations were recruited. Control infants were fed with the STD bottles used in the hospital and experimental counterparts were offered the SP feeding system. The subjects were considered “feeders and growers” with no clinical diagnoses preventing their discharge home, but for their inability to take all feedings by mouth. The study was approved by the Baylor College of Medicine Institutional Review Board. Consents from attending neonatologists and parents were obtained.

Study Design

Introduction and advancement of oral feedings were left to the discretion of infants’ attending neonatologists. Infants were monitored at 2 time points, when taking 1 to 2 and 6 to 8 oral feedings per day. They were left undisturbed for 30 min prior to the monitored sessions to minimize fatigue prior to oral feeding. Caregivers were asked not to ‘encourage’ infants during the feedings, i.e., to allow infants to pause/rest as needed. A maximum feeding duration of 20 min was followed as per hospital policy. Any remaining volume was given through a naso- or oro-gastric tube.

Outcome Measures

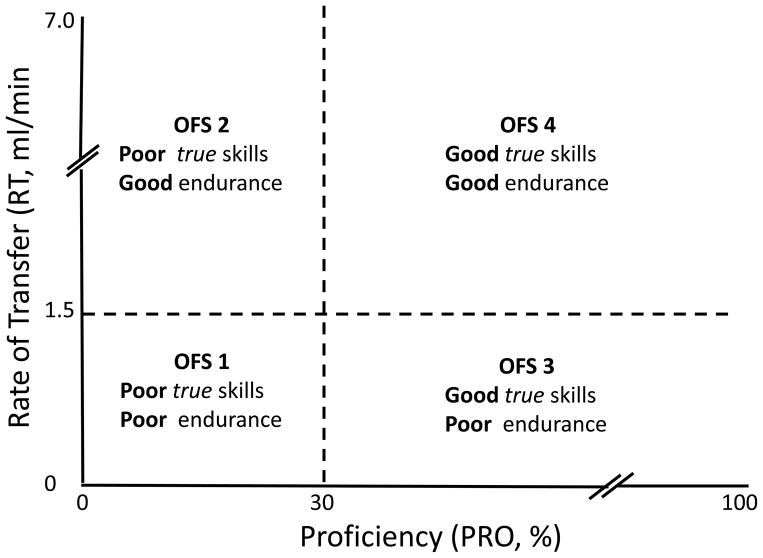

Oral feeding performance was monitored as a function of OT. RT over an entire feeding (RT; ml/min) and proficiency (PRO; % volume taken at 5 min/volume prescribed) were used to compute infants’ OFS levels 4. Four levels were defined (Fig. 3): level 1, the most immature, defined with PRO < 30%, RT< 1.5 ml/min; level 2 with PRO < 30%, RT≥ 1.5 ml/min; level 3 with PRO ≥ 30%, RT< 1.5 ml/min; and level 4, the most mature, with PRO ≥ 30%, RT ≥ 1.5ml/min. The threshold cutoffs for PRO and RT, 30% and 1.5 ml/min, respectively, were based on a study conducted on a group of preterm infants born within the same gestational range 5. This scale was developed based on the premise that infants’ feeding during their first 5 min, as measured by PRO, most closely represented their ‘true’ OFS when fatigue was minimal. In contrast, RT monitored over the entire feeding, would reflect their OFS as fatigue came into play, if any. As such, the 4 OFS maturity levels defined as a function of PRO and RT offered a means to differentiate between infants’ true skills and fatigue or their lack of endurance. Depending upon whether these two outcomes fell above or below their respective threshold (30% and 1.5 ml/min, respectively), they were described as ‘poor’ or ‘good’ (Fig. 3). Episodes of adverse events, i.e., oxygen desaturation, apnea, and/or bradycardia, whether self-resolved or not, were recorded.

Figure 3.

Oral Feeding Scale (OFS) levels 1 to 4

Statistics

Continuous measures between study groups were analyzed using the independent t-test and multiple regression analyses. Categorical outcomes utilized Chi-Square.

Results

No significant differences were noted in subjects’ characteristics between groups (Table 1). Oral feeding outcomes, OT, RT, and PRO were significantly greater in the SP- vs. STD-fed infants at 1–2 and 6–8 oral feedings per day (Table 2). No adverse events occurred that did not self-resolved.

Table 1.

Subjects’ Characteristics

| Feeding Bottle | Standard | Self-Paced | p* |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| N | 15 | 15 | 0.738 |

|

| |||

| Gender (male/female) | 9/6 | 10/5 | 0.705** |

|

| |||

| Gestational Age (weeks) | 27.7 ± 1.2 (26–29) # | 27.9 ± 1.0 (26–29) | 1.000** |

| (26–27)/(28–29) | 6/9a | 6/9 | |

|

| |||

| Birth Weight (g) | 956 ± 276 (560 – 1300) b | 1037 ± 200 (727–1310) | 0.365 |

|

| |||

| PMA (weeks)## at: | |||

| 1–2 oral feedings/day | 34.3 ± 1.0 (33–37) | 34.2 ± 0.8 (33–36) | 0.695 |

| 6–8 oral feeding/day | 36.3 ± 1.5 (34–39) | 36.8 ± 2.0 (34–42) | 0.425 |

Mean ± SD (range)

PMA: postmenstrual age

Number of infants per GA strata

(range)

Independent t-test

Chi Square

Table 2.

Overall feeding outcomes

| Oral Feedings/day | 1–2 | p* | 6–8 | p* | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Standard | Self-Paced | Standard | Self-Paced | |||

| Overall Transfer (%) | 50.09 ± 32.02# | 93.64 ± 13.71 | <0.001 | 70.18 ± 34.18 | 97.20 ± 10.83 | 0.007 |

| Efficiency (EFF; ml/min) | 0.94 ± 0.55 | 2.41 ± 0.80 | <0.001 | 1.71 ± 0.92 | 4.48 ± 1.46 | <0.001 |

| Proficiency (PRO; %) | 18.0 ± 11.0 | 41.2 ± 14.7 | <0.001 | 27.1 ± 16.4 | 55.7 ± 19.7 | <0.001 |

Mean ± SD

independent t-test between groups at each period

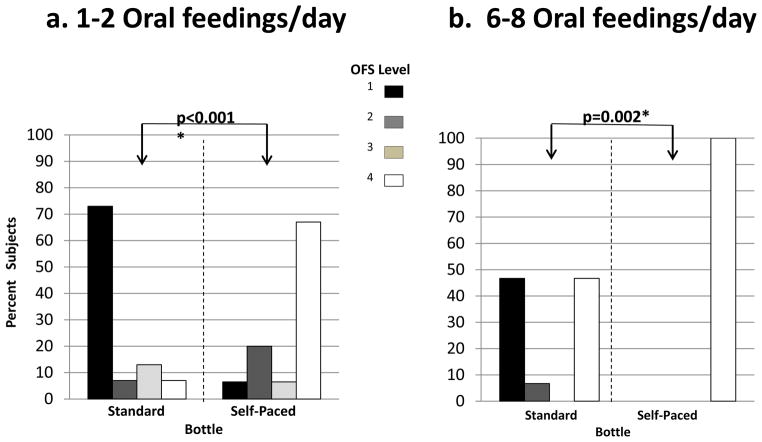

Figures 4a, b show the OFS profiles of both groups at 1–2 and 6–8 oral feedings/day, respectively. Infants within both groups and at both monitored times exhibited all 4 OFS levels. Over time, most infants showed trends towards more mature OFS. However, the majority of infants fed with the SP system demonstrated more mature OFS levels than control counterparts at both monitored sessions (p≤0.002). Of note, SP infants were all operating at the most mature OFS level 4 when taking 6–8 oral feedings per day. This contrasts with 6 of the 15 STD infants who were still using the most immature OFS level 1. Table 3 shows infants’ OT performance and number of infants per OFS levels when fed with the STD bottle and SP system at 1–2 and 6–8 oral feedings per day.

Figure 4.

OFS profiles of VLBW infants feeding with a standard vs. self-paced bottle when taking: a. 1 to 2 oral feedings per day; b. 6 to 8 oral feedings per day

Table 3.

Overall Transfer by OFS levels

| 1–2 Oral Feedings/day | 6–8 Oral Feedings/day | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Oral Feeding Skills | Standard | Self-Paced | Standard | Self-Paced |

| Level 1 (n) | 39.3 ± 25.5 (11) # | 62.5 (1) | 36.17±13.64 (7) | - |

| Level 2 (n) | 100 (1) | 100 ± 0 (3) | 100 (1) | - |

| Level 3 (n) | 59.9 (2) | 80 (1) | - | - |

| Level 4 (n) | 100 (1) | 96.2 ± 12.0 (10) | 100 0 (7) | 92.2 10.8 (15) |

Mean ± SD (number of infants)

Multiple regression analyses demonstrated that OT was positively correlated with OFS levels (p<0.001), but not GA (p≥0.498) at 1–2 and 6–8 oral feedings per day.

Discussion

With the use of our recently developed OFS scale4, this study confirms the advanced hypothesis that VLBW infants’ improved oral feeding performance was associated with more mature OFS when fed with the SP feeding system vs. STD bottles. We advance that the benefits of the SP system resulted from the elimination of both hydrostatic pressure and internal vacuum build-up; both of which are inherent properties of a STD bottle as it empties during a feeding. The observed positive correlation between OFS levels and OT, i.e., the more mature the skills, the better the OT, is a first account providing evidence of an ‘interplay’ between infants’ true nutritive skills and fatigue. Indeed, the OFS scale, as conceived, is not only a measure of an infant’s oral feeding ability during bottle feeding, but one that offers a unique means to differentiate between the interactive impacts, be they positive or negative, of infants ‘true’ oral feeding skills (when fatigue is minimal)and fatigue itself. Such information is valuable because caregivers have long recognized that infants’ sucking ability and their endurance (or lack thereof) affect oral feeding performance. However, with no means available to differentiate between the respective impacts of these 2 elements, it has remained difficult to determine the best therapeutic approach (es) to use when assisting infants with oral feeding difficulties, e.g., is a poor oral feeding the result of poor skills and/or poor endurance?

Another observation of value made herein relates to how feeding tools can affect infants’ oral feeding performance. Little attention has been placed on the type of bottle best suited for infants born prematurely or with anomalies. Bottle feeding is an old science6 and the conception of a feeding bottle has not changed substantially over centuries, but for its shape, size, and material used. Feeding bottles have been developed with term infants in mind as survival of preterm infants was scarce. However, with the increased survival of infants born ever more prematurely, the increased concerns over these infants’ oral feeding difficulties warrant a renewed investigation in the development of feeding bottles. Over the last 2 decades, research has offered a greater understanding of the development of preterm infants’ oral feeding skills and with their immature functional skills, the century-old feeding bottle may no longer be appropriate. Indeed, what works for a term infant may not be appropriate for a preterm infant. This is well illustrated in the present report by VLBW infants who, on their own, used more mature and efficient oral feeding skills with the SP feeding system vs. the STD bottle. This highlights the importance of using appropriate tool(s) that take into account their pathophysiologic and/or maturational limitations in order to optimize performance.

The fact that infants within the same gestational and postmenstrual age can exhibit the 4 OFS levels as they advance towards independent oral feeding raises concern over our inability as caregivers to accurately determine their oral feeding ability be it due to inadequate feeding skills and/or fatigue. Consequently, decisions to encourage completion of a feeding or to advance daily oral feedings as currently practiced may be inappropriate. It is conceivable that the large number of infants born prematurely followed in feeding disorder clinics is a resultant of such approach7,8.

In summary, we have shown that the presence of the hydrostatic pressure and vacuum build-up physically occurring in the STD bottles currently in use hamper the feeding performance of VLBW infants. Three important recognitions are revealed in the present: 1. VLBW infants have more mature OFS than recognized; 2. the physical properties inherent to standard bottles currently in use put them at a disadvantage and are likely causes for some of their oral feeding issues; 3. the development of any tool to assist these infants ought to be built around their functional limitations, be they a result of prematurity or other anomalies.

Acknowledgments

Financial Support: Funding from the National Institutes of Health (R01-HD28140, R01 HD044469)

This study was supported by grants from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (R01-HD28140, R01 HD044469) and the General Clinical Research Centers Program (M01-RR-00188).

Abbreviations

- GA

Gestational age

- OFS

Oral feeding skills

- OT

Overall transfer

- PMA

Postmenstrual age

- PRO

Proficiency

- RT

Rate of transfer

- SP

Self-paced

- STD

Standard

Footnotes

The contents of this publication are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development or the National Institutes of Health.

Potential conflict of interest: First author has financial interests relevant to the self-paced oral feeding system as per her receipt of a Phase 1 SBIR funding (R43HD072847).

References

- 1.American Academy of Pediatrics. Policy Statement, Hospital discharge of the high-risk neonate. Pediatrics. 2008 Nov;122(5):1119–1126. doi: 10.1542/peds.2008-2174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lau C, Schanler RJ. Oral feeding in premature infants: advantage of a self-paced milk flow. Acta Paediatr. 2000 Apr;89(4):453–459. doi: 10.1080/080352500750028186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fucile S, et al. A controlled-flow vacuum-free bottle system enhances preterm infants’ nutritive sucking skills. Dysphagia. 2009 Jun;24(2):145–151. doi: 10.1007/s00455-008-9182-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lau C, Smith EO. A Novel Approach to Assess Oral Feeding Skills of Preterm Infants. Neonatology. 2011 Jan;100(1):64–70. doi: 10.1159/000321987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lau C, et al. Oral feeding in low birth weight infants. J Pediatr. 1997 Apr;130(4):561–569. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(97)70240-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Stevens EE, Patrick TE, Pickler R. A History of Infant Feeding. J Perinat Educ. 2009;18(2):32–39. doi: 10.1624/105812409X426314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lau C, Hurst N. Oral feeding in infants. Curr Probl Pediatr. 1999 Apr;29(4):105–124. doi: 10.1016/s0045-9380(99)80052-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Burklow KA, et al. Classifying complex pediatric feeding disorders. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 1998 Aug;27(2):143–147. doi: 10.1097/00005176-199808000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]