Abstract

A parent’s distress is known to color children’s experiences of their families. Studies, however, have rarely focused on the levels of distress experienced by fathers, and in particular, as they affect the emotional experiences of their children. We examine the impact that fathers’ experience of distress throughout their children’s early years has on children’s emerging narrative representations of father-child relationships and of family conflict and cohesion. In this longitudinal investigation, fathers of young children reported their distress on two occasions in relation to self, the marital relationship, and the family climate. Fathers also concurrently reported on their children’s temperament, specifically negative emotionality. Children responded to story stem beginnings about challenging situations in the family and their narratives were scored for dysregulated negative-disciplinary and positive parental behaviors of fathers, family conflict themes, and family harmony themes. It was hypothesized that children of more distressed fathers would represent greater dysregulated fathering and higher levels of family conflict, and lower levels of positive fathering and family harmony than children of less distressed fathers. Further, the study examined whether this effect was mediated through the fathers’ reports of their children’s negative emotionality. Results partially supported the hypothesized direct and indirect effects. Children’s narratives of negative-disciplinary fathering and family conflict were more common in boys when fathers reported greater distress, and temperament ratings fully mediated this effect. However, their narratives of positive fathering and family harmony were not significantly affected. That positive family features were preserved in children’s narratives even in the face of greater father distress suggests that families may be able to build resilience to internalized distress through these positive narrative features.

Keywords: paternal distress, temperament, child narratives, longitudinal, Structural Equation Modeling

INTRODUCTION

The rapidly changing roles of fathers within contemporary family structures and accumulating evidence regarding fathers’ influence on children’s development (e.g., Lamb, 2010) have generated increasing scholarly interest in fatherhood and fathering. Some research suggests that fathers are influential in promoting children’s emergent understanding of family roles and relationships (Stolz, Barber, & Olsen, 2005), but this area of research remains understudied. Of particular interest are fathers’ contributions to the emotional experience of their children in the family.

The proposed model in the current investigation is grounded in Belsky’s (1984) model of parenting and attachment theory. Generally speaking, Belsky asserts that how parents structure and experience parenthood is influenced by a constellation of factors, including parent characteristics (e.g., parents’ personality), child characteristics (e.g., temperament of the child), and the levels of stress and support parents experience within their environments, both inside and outside of the family. These shapers of parenthood influence the development of children both directly and indirectly. Accordingly, several theoretical frameworks suggest that negative personality characteristics of fathers combined with greater levels of stress within the family should have a negative impact on how children experience and represent their family life.

According to attachment theory, early parent-child interactions are the foundation for developing internal working models of relationships, which shape how individuals perceive and respond to others (Bowlby, 1982). Internal working models include representations of interpersonal and emotional experiences that influence behaviors and representations of others and carry forward throughout development (Bowlby, 1982; Bretherton, 1985, 1987). Although the majority of attachment research has focused on mothers, a growing body of literature supports the importance of children’s attachment to fathers (e.g., Bretherton, 2010; Freeman, Newland, & Coyl, 2010; Newland, Coyl, & Freeman, 2008). A meta-analysis performed by Lucassen and colleagues (2011) found consistent associations between paternal sensitivity and greater infant-father attachment security, and paternal attachment appears to be particularly relevant for children’s later peer relationships (Michiels, Grietens, Onghena, & Kuppens, 2010). Attachment theory informs the present study in specific ways. It is reasonable to assert that the levels of distress experienced by fathers will impact the security/anxiety experienced by young children and, therefore, filter into children’s working models of adults and relationships (Oppenheim & Waters, 1995). Put another way, children with distressed fathers would be expected to develop negative representations of their fathers and family environments. However, the formation of such representations is complex and cannot be explained simply by fathers’ experiences or behaviors. Notably, Bost, Choi and Wong (2010) found that greater paternal hostility and intrusiveness were associated with a higher number of negative emotional references from children during father-child reminiscing if parents also perceived their children’s temperaments as being difficult. Therefore, father distress, potentially in combination with perceptions of their children as having difficult temperaments that influences children to develop negative representations of their fathers and families. These negative representations are presumed, according to attachment theorists, to play a role in the social and emotional development of children and in their relationships with others within and beyond the family over time (Bretherton, 1990; Cassidy & Shaver, 1999; Suess, Grossmann, & Sroufe, 1992).

Attachment theory is also used in the present study to provide a perspective on how parents develop representations of their own children. Research suggests that adults’ parenting representations of their children are colored by their own working models (Bartholomew & Horowitz, 1991; Benoit, Zeanah, Parker, Nicholson, & Coolbear, 1997; Main, Kaplan, & Cassidy, 1985). That is, a parent’s construal of his/her child (for example, the child’s positive or negative temperament) involves appraisals based on the parent’s internalized working model. Furthermore, parental perceptions of child temperament are associated with the quality of parent-child interaction (Kochanska, 1998; Pettit & Bates, 1989). Much of this work has arisen from studies using the Working Model of the Child Interview, an interview measure designed to capture parents’ subjective perceptions of and relationship with their infants (Zeanah, Benoit, Hirshberg, Barton, & Regan, 1994), and the work of Bretherton and colleagues about the development and importance of both parents’ and children’s working models (Bretherton, 1985, 1987; Bretherton, Biringen, Ridgeway, Maslin, & Sherman, 1989). Thus, parents’ working models influence parent appraisals which, in turn, underlie both thoughts and behaviors in relation to the child, that then contribute to the relationship parents have with their children, the child’s working models, and children’s meaning-making about family relationships (Goldwyn, Stanley, Smith, & Green, 2000).

Paternal Distress

Compared to maternal distress, less research has been done on the role of father’s psychological distress in the family. According to Belsky’s model (Belsky, 1984), a parent’s experience of distress, and of parenthood itself, might be influenced by multiple sources, including personality characteristics, marital dissatisfaction, and a family climate dominated by conflict. Although less research exists to support these sorts of influences for fathers than exists for mothers, similar processes appear to be at work in terms of the ways fathers structure and experience parenthood. Regarding the influence of personality, people high in neuroticism (the personality dimension describing negative emotionality) tend to be easily distressed, anxious, tense, and less emotionally stable (Costa & McCrae, 1980). Regarding the influence of personality for fathers, two previous studies found that fathers’ personality characteristics such as neuroticism (i.e., level of anxiety, hostility, and depression) were predictive of destructive parent-child interaction (Belsky, Crnic, & Woodworth, 1995; Clark, Kochanska, & Ready, 2000). As such, personality factors appear to influence fathers’ parenting experiences and behaviors.

Considerable evidence also has suggested that marital conflict contributes substantially to psychological distress (Holt-Lunstad, Birmingham, & Jones, 2008; Marcussen, 2005; Proulx, Buehler, & Helms, 2009; Stoneman, Brody, & Burke, 1989). An overlap exists in the literature between individual distress and marital dissatisfaction, with some research suggesting that in 30% of couples who have marital problems, at least one partner also is seriously psychologically distressed (Gotlib, 1992). Although studies on this topic typically are correlational, there is some evidence that marital discord can lead to the onset of psychological distress, including depression, and the maintenance of symptoms in adults (e.g., Fincham, Beach, Harold, & Osborn, 1997), but also that psychologically distressed individuals are more likely to have unhappy marriages (Kronmuller et al., 2011). As such, levels of marital conflict and satisfaction are important to assess when accounting for factors that influence fathers’ distress and therefore, their experience of parenthood.

More broadly, aspects of the family climate influence the distress experienced by fathers. For example, McCabe and Gotlib (1993) found that adults who view their family climate in a negative light tend to experience more depressive symptoms. Other studies suggest that in families where there is less conflict individuals can feel a greater sense of self worth (Lange, 2003; Sinacore & Akcali, 2000). In contrast, Foster et al. (2008) found that parents who reported more depressive episodes in their lifetime exerted less parental control within the family. Overall, paternal and family attributes may have continued consequences for young children in the family.

Paternal Perceptions of Children’s Temperament

Among the most important predictors of the quality of the parent-child relationship is the child’s temperament (e.g., Chess & Thomas, 1996) defined as individual differences in emotional, motor, and attentional reactivity (Rothbart, 2007) that are influenced over time by heredity, maturation, and experience (Rothbart, 1989). These early individual differences elicit various forms of child-caregiver interaction (Crockenberg, 1986) that subsequently influence developmental processes within the child, including genetic, physiological, and individual aspects (Thelen, 1995). Although temperament is a characteristic of the child, temperament most often is assessed through parent report, and thus ratings of temperament reflect both objective qualities of the child as well as the parent’s subjective experience of the child (Mebert, 1991). Several studies used temperament questionnaires as a predictor of parents’ representations of their child gathered through interview (e.g., Mebert; Wolk, Zeanah, Garcia Coll, & Carr, 1992). They found that parents’ representations of their children’s temperament were influenced negatively by their own level of distress in the relationship. Specifically, whether parents described infant temperament as easy or difficult was associated with parental psychological dispositions and characteristics. In other studies, infants rated as “difficult” had mothers who were more anxious, more depressed, lower in self-esteem, and more impulsive (Daniels, Plomin, & Greenhalgh, 1984; Vaughn, Bradley, Joffe, Seifer, & Barglow, 1987). Milgrom and McCloud (1996) also reported that depressed mothers rated their infants as less adaptable, more moody, and more demanding than did mothers without depression. In addition, researchers have shown that some parents’ perceptions of child temperament are moderately stable from pregnancy to the early years of life (Mebert, 1989, 1991; Zeanah, Keener, Stewart, & Anders, 1985). Taken together, these studies suggest that parents’ appraisals of their children’s temperament appear to be influenced by both objective and subjective factors. When parents are distressed, they are more likely to “see” similar distress in their children, and this is reflected in their ratings of the emotional qualities of their children’s temperament; unfortunately, such studies have not been conducted with fathers.

Overall, the experiences, expectations, and behaviors of parents are important determinants of child well-being over time. Current research suggests that both individual (personality, distress) and family-level (marital discord, family climate) variables can influence the experience of parenthood, and particularly parents’ levels of distress. We know that parental distress tends to have negative impacts on child well-being and parent-child relationships (Belsky, Crnic, & Woodworth, 1995; Clark, Kochanska, & Ready, 2000). Specifically, parents’ negative experiences and distress adversely affect children overall because such parental distress “spills over” into the perceptions and attributions parents have about their children (appraisals of child temperament). Expectations about children shape parent-child interactions, which in turn influence the ways that children view relationships with parents (Easterbrooks & Emde, 1988). Spillover of emotion is generally defined as the direct transfer of stress, mood or behavior from one person to another (Bolger, DeLongis, Kessler, & Wethington, 1989). In the long run, attachment and early parent-child relationships have implications for children’s relationships with peers and teachers (Page & Bretherton, 2001) and later relationships with their own children (Bretherton, 1990). Such long term implications are beyond the scope of the current study, but emphasize the importance of studying these early processes. Unfortunately, most of this research has been conducted with mothers (e.g., Daniels et al., 1984; Milgrom & McCloud, 1996; Vaughn et al., 1987) leaving a gap in our understanding of the experiences and contributions of fathers to such processes.

Children’s Representations of Fathers and Family

From infancy onward, children develop representations of family relationships through daily interactions with parents, siblings, and other involved family members, reflecting a core principle of attachment theory, the internal working model (Oppenheim & Waters, 1995; Waters, Rodrigues, & Ridgeway, 1998). Such working models include children’s ideas and expectations about parental roles and family harmony and conflict. As early as the preschool years, children are able to convey these representations through story stem narrative portrayals of their experience (Oppenheim, 2006). Direct empirical support for this is found in a study that compared the three- and four-year-old children of depressed and non-depressed mothers (Toth, Rogosch, Sturge-Apple, & Cicchetti, 2009). They found that a history of depression affected the child’s positive and negative parent representations and was mediated by children’s attachment security. Furthermore, mothers who were treated for depression in this randomized control trial were more likely to have children whose representations were more positive and less negative.

Parent reported marital distress also has been linked to young school age children’s family narratives. Shamir, Schudlich, and Cummings (2001) found direct associations between parents’ report of marital conflict and children’s representations of family relationships. When either parent reported responding to conflict in the marriage with more destructive strategies (verbal and physical aggression, stalemating), their children’s family representations included more negative and fewer positive themes. Also, research supports the use of children’s narratives as a way of assessing children’s attachment to their fathers as well as mothers (Page, 2001). Taken together, there is strong evidence that children’s narratives offer a window into the child’s meaning making of parent-child relationships and their experience of conflict in the family environment. However, few studies have examined the direct links between parental ratings of temperament and child representations of family (Bretherton, Ridgeway, & Cassidy, 1990; Goldwyn, Stanley, Smith, & Green, 2000). As such, the mechanisms linking parental distress and children’s family representations are still ambiguous. A story stem method to elicit young children’s representations, called the MacArthur Story Stem Battery (MSSB), has developed a considerable empirical base in the past 20 years (see Holmberg, Robinson, Weiner, & Corbitt-Price, 2007, and Oppenheim, 2006, for reviews).

Twins

Having twins can place increased stress on families compared to families of singletons (Thorpe, Golding, MacGillivray, & Greenwood, 1991). Parents with twins experience increased parenting demands and, thus, can face inadequate sleep, lack of time to care for other children, mood fluctuations, disturbance in the marital relationship, and financial strain (Chang, 1990; Robin & Casati, 1994). Although most of these problems might decrease as the twins grow older, emotional disturbances might continue (Chang, 1990). Research suggests that, among parents of twins, parenting stress significantly predicted parents’ overall psychological well being, over and above social support available and the presence of other children in the home (Colpin, De Munter, Nys, & Vandemeulebroecke, 1999, 2000). Parents of twins tend to experience multiple demands and higher parenting stress in parent-child interactions (Lytton, Singh, & Gallagher, 1995). However, there is variability with regard to levels of stress couples experience after the birth of a child (Levy-Schiff, 1994), and Taubman-Ben-Ari et al. (2008) found that having twins compared to a single child did not predict poorer marital adaptation.

The Current Study

This study examines the impact that fathers’ experience of distress throughout their children’s early years has on the children’s emerging representations of their fathers and of the overall emotional climate within their families. The literature reviewed suggests that long-term paternal psychological distress might have direct and indirect influences on children’s representations of fathers and family conflict and cohesion. In the present study, we examined models of the long-term direct and indirect effects of paternal distress on children’s representations of fathers and family harmony and conflict. As fathers’ levels of distress might spill over into their views of their children, we included fathers’ report of child temperament as a potential mediating link between their self-reported distress and children’s representations. That is, we explored whether fathers’ negativity and distress were related directly to their children’s representations of fathers and families or mediated through the attributions fathers made regarding child temperament. We conducted this investigation using data gathered from the MacArthur Longitudinal Twin Study and as such, also address the unique family circumstance of parents raising two same-aged children.

The current large, longitudinal sample of families of twins was studied at child ages 14 months and 5 years. On the basis of structural equation model analyses, three main hypotheses were tested. First, we expected that paternal distress reported at child age 1 and 5 years would be associated with the tendency for fathers to negatively represent emotional aspects of their children’s temperament. Second, we anticipated that paternal distress would result in children developing less positive and more negative representations of father-child relationships, family discord, and family harmony at age 5 years. Third, we hypothesized fathers’ representations of children’s temperament would mediate the association between paternal distress and children’s representations of fathers and families. Fathers’ representations of temperament were used as a mediator rather than a moderator due to the relatively consistent and linear associations between parental distress and parental ratings of temperament. That is, father representations of child temperament were conceptualized as a link between fathers’ own distress and children’s negative representations, rather than as a conditioning or moderating variable.

METHOD

Participants

Participants were same-sex twin pairs recruited through birth records from the Colorado Department of Health between 1986 and 1990 for the MacArthur Longitudinal Twin Study (LTS) (Emde & Hewitt, 2001). Although longitudinal behavioral genetics questions drove the design of the study, investigators also intended to address questions about the role of family environment characteristics (see Emde & Hewitt, 2001). Three hundred nineteen fathers and their twins participated in the study at child age one through five (See table 2 for the details). Families were selected particularly for twin births that met the criteria of having a birth weight of 1,700g or more; those with medical complications were excluded. Fathers’ average age at time of twin birth is 31.7 years (range, 20–52). The ethnicity distribution of the participants in the LTS is 86.6% Caucasian, 8.5% Hispanic, 0.7% African-American, 1.2% Asian, and 2.9% other, and corresponds well to that reported for Boulder County, Colorado, in the 1990 United States Census. The average education of fathers was 14.61 years (sd = 2.12, range 9–21 years); 2.9% did not complete high school, 26.6% completed high school without post-secondary education, 49.7% had some post-secondary education, and 20.8% had some graduate-level education. Fathers participating in the study were higher educated than the average fathers of twins born during the recruitment period. The mean of NORC (National Opinion Research Council) occupation for fathers is 48.59 (sd = 13.59) (Robinson, McGrath, & Corley, 2001). Thirty one fathers were divorced throughout the entire first 5 years of the study children’s lives. Further information regarding the LTS is available in Rhea, Gross, Haberstick, and Corley (2006).

Table 2.

Descriptive Statistics

| 14 Months (total n = 319)

|

5 Years (n = 189)

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | M (SD) | Min-Max | n | M (SD) | Min-Max | |

| Paternal Distress | ||||||

| EPI | 295 | 7.98 (4.50) | 0–23 | 183 | 6.71 (4.26) | 0–21 |

| DAS | 290 | 111.17 (14.91) | 45–143 | 171 | 112.46 (13.23) | 70–145 |

| FES | 294 | 1.64 (1.42) | 0–5 | 184 | 1.93 (1.29) | 0–5 |

| Temperament Ratings | ||||||

| CCTI: Emotionality twin 1 | 283 | 14.61 (3.84) | 6–24 | 189 | 14.11 (3.37) | 5–25 |

| CCTI: Emotionality twin 2 | 279 | 14.95 (3.92) | 5–25 | 185 | 14.39 (3.37) | 6–25 |

| 5 Years (n = 544)

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Girls (n = 268) | Boys (n = 276) | |||||

| Child Representations of fathers | ||||||

| Negative-disciplinary father twin 1 | 134 | .07 (.09) | 0–.42 | 138 | .10 (.10) | 0–.42 |

| Negative disciplinary father twin 2 | 134 | .08 (.09) | 0–.42 | 138 | .12 (.10) | 0–.42 |

| Positive father twin 1 | 134 | .10 (.14) | 0–.67 | 138 | .10 (.14) | 0–.67 |

| Positive father twin 2 | 134 | .11 (.12) | 0–.67 | 138 | .10 (.13) | 0–.50 |

| Child Representations of families | ||||||

| Distress twin 1 | 134 | .22 (.33) | 0–1.83 | 138 | .22 (.36) | 0–2.00 |

| Distress twin 2 | 134 | .28 (.36) | 0–1.60 | 138 | .22 (.35) | 0–2.20 |

| Anger twin 1 | 134 | .70 (.49) | 0–2.17 | 138 | .65 (.52) | 0–2.33 |

| Anger twin 2 | 134 | .73 (.59) | 0–2.50 | 138 | .61 (.49) | 0–2.33 |

| Aggression twin 1 | 134 | .07 (.11) | 0–.42 | 138 | .15 (.14) | 0–.50 |

| Aggression twin 2 | 134 | .07 (.09) | 0–.50 | 138 | .15 (.16) | 0–.80 |

| Escalation of Conflict twin 1 | 134 | .08 (.14) | 0–.67 | 138 | .13 (.17) | 0–.67 |

| Escalation of Conflict twin 2 | 134 | .10 (.15) | 0–.67 | 138 | .15 (.17) | 0–.67 |

| Affiliation twin 1 | 134 | .21 (.18) | 0–.67 | 138 | .15 (.15) | 0–.67 |

| Affiliation twin 2 | 134 | .20 (.19) | 0–1.00 | 138 | .14 (.13) | 0–.60 |

| Affection twin 1 | 134 | .22 (.17) | 0–.80 | 138 | .17 (.13) | 0–.50 |

| Affection twin 2 | 134 | .22 (.17) | 0–.83 | 138 | .16 (.14) | 0–.67 |

| Empathy/Helping twin 1 | 134 | .14 (.15) | 0–.60 | 138 | .12 (.14) | 0–.50 |

| Empathy/Helping twin 2 | 134 | .18 (.18) | 0–.83 | 138 | .14 (.15) | 0–.67 |

Procedures

For the current investigation, data were collected during a home visit and a laboratory visit at child ages 14 months and 5 years. A home visit was planned for times when it was convenient for parents and when the children were well rested. Several questionnaires were given to the father to complete including (1) the Eysenck Personality Inventory (Eysenck & Eysenck, 1969), (2) the Dyadic Adjustment Scale (Spanier, 1976), (3) the Family Environment Scale (Moos & Moos, 1981), and (4) the Colorado Childhood Temperament Inventory (Buss & Plomin, 1984; Rowe & Plomin, 1977). For children, the Stanford-Binet IQ test (Terman & Merrill, 1973) and the vocabulary subtest in Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children-Revised (Wechsler, 1974) were conducted during the home visit at child age 4 years. Story stem narratives were administered to children at the 5 year home visit. Each child was asked to complete stories by manipulating a set of dolls and props and verbalizing actions using the dolls.

Measures

Paternal distress

The measure of distress is drawn from three sources of paternal experience: psychological, marital, and family relations. Psychological distress was assessed via the Eysenck Personality Inventory (Eysenck & Eysenck, 1969). The EPI describes an individual’s personality on three dimensions: (1) an Extraversion Scale; (2) a Neuroticism Scale; and (3) a Lie scale. For the current study, Neuroticism, an indicator of psychological distress in response to stressors, was used to represent the psychological aspect of paternal distress. Neuroticism consists of 24-items that are answered with “yes” or “no” (e.g., Do you often worry about things you should have done or said?). Previous research has reported reliability coefficients for this scale at .71–.78 (Bolger & Shilling, 1991; Muniz, Garcia-Cueto, Lozano, 2005). In the current sample, alphas for neuroticism were .81–.82 across the two assessments.

At the marital level, we used the Dyadic Adjustment Scale (DAS: Spanier, 1976), a self-report instrument completed by partners in a relationship to characterize its quality. Respondents are asked to rate 32-items on a 5-point Likert-type scale. The DAS includes four subscales: (1) Dyadic Consensus; (2) Dyadic Cohesion; (3) Dyadic Satisfaction; and (4) Affectional Expression. A total adjustment score is calculated by summing across the four subscales. For the present study, fathers’ total scores were used as indicators for marital distress. The DAS has established validity with other measures of marital adjustment (Spanier). In addition, the alpha for the total adjustment score has been reported at .96 (Spanier). In the current sample, alphas ranged from .79–.82 across the two assessments.

The Family Environment Scales (FES; Moos & Moos, 1981) were developed to measure social and environmental characteristics of families. For the present study, items from the Conflict scale (e.g., amount of openly expressed anger and conflict among family members) were used. The FES consists of 40 “true” or “false” items rated by parents. Adequate validity and reliability have been reported (Moos & Moos, 1981). In the present study, internal consistency was relatively low for the combined 5 items from conflict subscale. Alphas ranged from .60–.69 across the two assessments. According to Moos (1990), the internal consistency of subscales is higher in more diverse samples. As such, the relatively low alphas in this study might be caused by our comparatively advantaged and less diverse sample.

Father ratings of child emotionality

Fathers’ ratings of children’s temperamental emotionality were measured by the Colorado Childhood Temperament Inventory (CCTI) (Buss & Plomin, 1984; Rowe & Plomin, 1977) at 14 months and 5 years. The measure contains 30 general statements. Emotionality is one of six temperament dimensions assessed, including activity, sociability, shyness, persistence, and soothability. Parents were asked to rate each statement on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1= strongly disagree; not at all like the child to 5 = strongly agree; a lot like the child. In this study, we used father ratings of emotionality, which evaluates the child’s tendency to become upset easily and intensely (e.g., “child cries easily”); it is most directly related to the spillover of father’s experience of his own distress. In the present study, alphas ranged from .74–.77 across the two assessments.

Children’s representations

Children’s representations of positive and negative-disciplinary qualities of father-child relationships, family harmony, and family conflict were measured at child age 5 years by the MacArthur Story Stem Battery (MSSB) (Bretherton, et al., 1990). The MSSB consists of 14 story stems used to elicit children’s narratives about emotionally charged themes. The story beginnings or stems involve family conflict or other potentially distressing circumstances (such as separation from parents or being caught breaking a rule about stealing). The examiner starts a story stem and then asks the child to tell the rest of the story using props and dolls (typically, mother, father, child, and in three stories a sibling doll) appropriate to each story. Each story is scored for presence-absence of relationship themes and emotions the child portrayed. Eight stories (Spilled Juice, Lost Dog, Gift to Mom or Dad, Lost Keys, Exclusion, Cookie Jar, Three’s a Crowd, and Bathroom Shelf) from the larger battery were coded for the entire twin sample using a scoring system described in Robinson and Mantz-Simmons (2003) that covers conflict and aggression, prosocial and moral themes, affects portrayed, and representations of parents as positive, negative, or disciplinary. A prior investigation demonstrated that the themes in these story stems elicited a significant amount of emotional engagement in children’s story-telling (von Klitzing, Kelsay, & Emde, 2003). Six stems that included the father were used in the present analysis (Spilled Juice, Gift to Mom or Dad, Lost Keys, Exclusion, Cookie Jar, and Three’s a Crowd). Two father representation variables were created: the percent of stories with a negative father representation (i.e., father behaves in a dysregulated way as a parent, such as excessive or severe punishments) and the percent of stories with a positive father representation (i.e., father enacts caretaking or protectiveness toward child). Two independent coders scored narrative protocols from videotape within twin pairs for all themes and affects. Interobserver reliability was based on independent scoring of the two raters for 72 randomly selected children. Intraclass correlations for negative-disciplinary father (ICC = .69) and positive father representations (ICC = .88) were acceptable.

Two thematic aggregates were created from a subset of the codes (see Table 1) and made into two latent variables of family-level representations. One aggregate reflected family conflict and was composed by averaging the presence of physical aggression and the escalation of conflict among any characters in the child’s stories, plus distress expressed or enacted by any story characters. Family harmony was comprised of the average of empathy/helping, affection, and affiliation themes about how the problem or conflict was resolved. Intraclass correlation showed acceptable inter-observer reliability: .80 for family conflict and .86 for family harmony.

Table 1.

Content Theme Definitions of the MacArthur Story Stems

| Father Representations | |

| Father Negative-disciplinary Representations | Father punishes, reprimands child; uses a hostile tone of voice to the child; rejecting requests to assist; father figure portrayed as dysregulated/frightening. |

| Father Positive Representations | A gentle, soothing parental tone of voice to child, offering help, caring or protection of child |

| Family Conflict | |

| Distress | Distress or fear expressed verbally, non-verbally and/or physically |

| Anger | Anger expressed verbally, non-verbally and/or physically |

| Aggression | Verbal and physical acts of aggression such as demeaning, hitting, pushing, kicking, or killing |

| Escalation of Interpersonal Conflict | Escalating the level of aggression beyond that evident in character’s first expression of aggression |

| Family Cohesion | |

| Affiliation | Situations in which 2 or more of the characters participate together in an activity |

| Affection | Any display of hugs, kisses, compliments, warm or caring touch, or praise |

| Empathy/Helping | Understanding of the thoughts or feelings of another through action or verbalizations, helping another character to do something |

Statistical Analysis

Structural equation modeling (SEM) was utilized to test the hypotheses using SPSS and Amos (v.19) in this study. The SEM process focused on validating the measurement model and employing the structural model. Measurement models evaluated by confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) were conducted to clarify the relationships among indicators and the underlying latent variables. Structural models were tested using path analysis between paternal distress indicators measured at two times (child age 14 months and 5 years), fathers’ representations of children’s temperament at two times (child age 14 months and 5 years), and children’s representations of family conflict, family harmony, and positive or negative-disciplinary representations of fathers at 5 years. Also, children’s sex, IQ, and verbal ability at child age 4 years were included as covariates in the structural model.

However, our model for analyzing twin data requires special adjustments to the standard SEM approach. Twins are considered to be interchangeable dyads and SEM for interchangeable dyads needs equality constraints (for more details, see Olsen & Kenny, 2006). The actor-partner interdependence model (APIM) for interchangeable dyads was applied to estimate the restricted model with the same estimated parameters and standard errors; it is used to estimate the interchangeable twin dyads model by forcing equality constraints on all parameters – means, variance, covariances, and paths (Kenny, Kashy, & Cook, 2006; Olsen & Kenny, 2006). This was appropriate because we had no a priori hypotheses about the influence of sibling relationships and differential twin relationships in this model. Finally, various fit indices are adjusted by making an adjustment to chi-square and degrees of freedom (Olsen & Kenny, 2006).

The first step involved developing confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) models for interchangeable twins. In this model, a measurement model relating the latent variable (e.g., children’s representations at age 5) to each of the indicators (e.g., anger, distress, aggression, escalation of interpersonal conflict) was developed for twin 1 and twin 2. Corresponding intercepts, factor loadings, and error variances were restricted to equality for the two twins. Second, analyzing interchangeable dyads data requires modifications to the measures of model fit. The chi-square and degrees of freedom need to be adjusted for the hypothesized model, instead using chi-square values from the new null model for indistinguishable dyads (I-NULL, for “interchangeable null”) and the new saturated model for indistinguishable dyads (I-SAT, for “interchangeable saturated”) (Olsen & Kenny, 2006). In this study, the I-SAT model was treated as the baseline to attain the adjusted chi-square and degrees of freedom by subtracting the chi-square and degrees of freedom from the I-NULL model. The model fit for the final model was assessed by constructing a chi-square difference test comparing the hypothesized model with I–SAT. Also, the adjusted chi-square values and the degrees of freedom then were used to compute additional fit indices (e.g., CFI, RMSEA; Olsen & Kenny, 2006). Kline (2005) described values of CFI greater than .90 as indicating a reasonably good fit of the hypothesized model. The RMSEA is a “badness-of-fit” index with values below .05 indicating good model fit and values between .05 and .08 indicating adequate fit (Kline, 2005). Lastly, we tested the mediating effects for significance using z-statistics and Sobel (1982)’s formula to estimate the standard error. In this study, the mediation effects were estimated by the product-of-coefficients methods which is the extended work of Sobel (1982) and Goodman (1960) to test longer meditational chains (more than one mediator in series; MacKinnon, Lockwood, Hoffman, West, & Sheets, 2002; Taylor, MacKinnon, & Tein, 2008).

Missing data were addressed using the Full Information Maximum Likelihood (FIML) method, which estimates means and intercepts. According to Enders (2001), in the case of missing completely at random (MCAR) or missing at random (MAR) patterns, FIML parameter estimates show less bias and are more appropriate than other methods, such as data deletion and mean imputation. In this study, a considerable number of missing data points occurred due to the fathers’ low response rate across the time points (see Table 2). To estimate whether data were MCAR, we examined the patterns of missing data using Little’s MCAR test (Little, 1988). The results of Little’s test suggested that the data were MCAR (χ2[2812] = 2241.348, p = 1.00). Accordingly, we retained the entire sample in analyses to maximize statistical power.

RESULTS

Descriptive Statistics

Table 2 presents the descriptive statistics of all key variables. Mean levels of paternal distress indicators showed stable mid-level scores on psychological distress with good distribution. However, over time, relatively high marital satisfaction, increasing levels of family conflict, and declining reports of neuroticism are shown. Fathers’ ratings of children’s emotionality in temperament indicate a normally distributed mean at the mid-point of the scale, with good variability.

In children’s narratives, research has suggested some evidence that child sex, cognitive and verbal abilities are closely related with children’s representations through their story telling (e.g., Fivush, Brotman, Buckner, & Goodman, 2000; Page & Bretherton, 2001). Accordingly, we included the child sex (girl = 0, boy = 1), IQ and verbal abilities as covariates in the study. Boys showed more negative-disciplinary father (t= 5.67, p < .05), whereas girls presented more family cohesion representations (t= 14.81, p < .001). Children’s IQ-level among twins was correlated with positive father representations (r= .13, p < .01), and children’s verbal ability was correlated with family cohesion representations (r= .12, p < .01). Bivariate correlations among the variables are presented in Table 3.

Table 3.

Summary of Bivariate correlations for Scores on EPI, DAS, FES, CCTI, MSSB, IQ, and WPPSI

| Measure | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. EPI 1Y | – | ||||||||||||||||||

| 2. DAS 1Y | −.372** | – | |||||||||||||||||

| 3. FES 1Y | .305** | −.420** | – | ||||||||||||||||

| 4. CCTI 1Y | .208** | −.128** | .158** | – | |||||||||||||||

| 5. EPI 5Y | .716** | −.281** | .156** | .157** | – | ||||||||||||||

| 6. DAS 5Y | −.187** | .276** | −.054 | −.113* | −.097 | – | |||||||||||||

| 7. FES 5Y | .239** | −.313** | .553** | .029 | .266** | −.143** | – | ||||||||||||

| 8. CCTI 5Y | −.064 | .065 | −.034 | .049 | .165** | .014 | .108* | – | |||||||||||

| 9. NEG-DCdad | .054 | −.104* | .084 | .033 | .023 | −.049 | .053 | .093* | – | ||||||||||

| 10. POSdad | .072 | −.050 | .043 | .000 | .117* | −.012 | .012 | .041 | .050 | – | |||||||||

| 11. DIS | .046 | −.039 | −.030 | −.004 | .099 | −.023 | .023 | .043 | .161** | .143** | – | ||||||||

| 12. ANG | .049 | −.040 | .036 | −.012 | .106* | .021 | .084 | .138** | .201** | .113** | .405** | – | |||||||

| 13. AG | .110* | −.141** | .086 | .057 | .117* | −.079 | .146** | .126** | .444** | −.021 | .253** | .436** | – | ||||||

| 14. EC | .057 | −.058 | .059 | .057 | .051 | .014 | .080 | .083* | .310** | .030 | .287** | .497** | .674** | – | |||||

| 15. AFL | −.066 | .038 | .002 | −.009 | −.050 | .099 | −.015 | .044 | −.043 | .081 | .130** | .240** | −.023 | .028 | – | ||||

| 16. AFC | .018 | −.035 | .062 | .094* | .079 | .067 | .084 | .076 | −.003 | .203** | .184** | .323** | .037 | .055 | .263** | – | |||

| 17. EH | .032 | −.020 | .051 | .051 | .062 | −.006 | .042 | .122** | −.037 | .254** | .180** | .264** | −.002 | .049 | .331** | .374** | – | ||

| 18. SBinet | −.025 | .052 | −.044 | −.030 | −.090 | .068 | −.061 | .032 | −.012 | .134** | .093* | .026 | −.039 | .053 | .008 | −.018 | .061 | – | |

| 19. WPPSI | −.089 | .037 | −.014 | −.152** | −.063 | .072 | −.028 | .106* | −.073 | .032 | .014 | −.036 | −.078 | −.070 | .133** | .018 | .116** | .095* | – |

Note. NEG-DCdad = Negative-Disciplinary father representation, POSdad = Positive father representation, DIS = Distress, ANG = Anger, AG = Aggression, EC = Escalation of interpersonal conflict, AFL = Affiliation, AFC = Affection, EH = Empathy/Helping.

p < .05,

p < .01.

Measurement Model

We tested confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) of paternal distress and children’s representations of family conflict and harmony. In the latent variable paternal distress, error correlation terms for similar indicators across the two time points were added between the observed variables: EPI, DAS, and FES. In addition, for the latent variable of children’s representations of family conflict, a correlated error term was added between the observed affect variables distress and anger, because of their frequent co-variation. The indicator loadings are reported in Table 4. For paternal distress, we found that all loadings were statistically significant at all time points. Findings suggested that the measure of paternal distress showed a good fit to the data (χ2[5] = 6.061, p > .10; CFI = .997; RMSEA= .026). Also, all loadings on the latent variable of children’s representations of family conflict and family harmony were statistically significant at p < .001. To take account of the special statistical issues in analyzing twin data, the fit of this model was tested using the chi-square difference between the I-SAT and the I-NULL model developed by Olsen and Kenny (2006). Analyses of the measurement model indicated a good fit to the data in children’s representations of family conflict (χ2[4] = 2.237, p > .10; CFI = .997; RMSEA= .037) and family harmony (χ2[1] = 1.579, p > .10; CFI = .996; RMSEA= .043).

Table 4.

Unstandardized Factor Loadings of Indicators with Latent Constructs in CFA

| Construct/Indicator | Unstandardized Factor loading | SE |

|---|---|---|

| Paternal Distress | ||

| 14 months | ||

| EPI | 1.000 | |

| DAS | −4.957*** | .901 |

| FES | .365*** | .061 |

| 5 years | ||

| EPI | 1.000 | |

| DAS | −3.571*** | .848 |

| FES | .396*** | .094 |

| Child Family Conflict Representations 5 years | ||

| Distress | 1.000 | |

| Anger | 2.566*** | .367 |

| Aggression | .928*** | .140 |

| Escalation of interpersonal conflict | 1.262*** | .195 |

| Child Family Harmony Representations 5 years | ||

| Affiliation | 1.000 | |

| Affection | 1.123*** | .184 |

| Empathy/Helping | 1.489*** | .275 |

p < .001

Structural Model

To investigate the structural model, we tested the paths between paternal distress, fathers’ representations of children’s temperamental negative emotionality, and children’s representations of negative-disciplinary fathers, positive fathers, family conflict, and family harmony. In addition, child sex, verbal and cognitive ability were included in the models as covariates.

Model 1: Paternal Distress and Father Report

In the first model, we tested whether paternal distress was associated with father ratings of child temperament at 14 months and 5 years. Paternal distress at 14 months was strongly related to later paternal distress at 5 years (B = .688, p < .001), indicating a high level of stability of paternal distress over time. Also, fathers’ reports of children’s negative emotionality in temperament from 14 months to 5 years (B= .208, p < .001) were moderately and positively associated, indicating substantial stability of the father’s view of his child’s temperament.

Paternal distress was positively related with fathers’ ratings of children’s temperamental negative emotionality at 14 months (B = .344, p < .001) and at 5 years (B = .308, p < .01). The indirect effect of paternal distress at 14 months on fathers’ ratings of temperament at 5 years via fathers’ ratings of temperament at 14 months was significantly different from zero according to the Sobel test (Z = 2.95, p < .01), but also significantly different from zero through paternal distress at 5 years (Z = 2.60, p < .01). Thus, fathers who experienced greater distress in the early years perceived more concurrent negative emotionality in their children’s temperament by age five years. After the chi-square values are adjusted, the re-specified model showed excellent fit to the data (χ2[16] = 22.038, p > .10; CFI = .986; RMSEA = .034).

Model 2: Father Report and Child Representations

Before fitting the full model, we tested structural models in which the latent variables of paternal distress were associated longitudinally and directly to the observed variables of children’s negative-disciplinary and positive representations of fathers as well as the latent variables of children’s family conflict and harmony representations. Child sex (girl = 0, boy = 1), cognitive and verbal abilities for twins who completed the children’s narratives at age 5 years were included in the model as covariates as well. The structural models were separately tested for children’s representations of negative-disciplinary and positive fathers and representations of family conflict and harmony themes. Separating the dependent measures allowed us to confirm that children’s representations of relationship with fathers (e.g., father-child dyadic-level relationship) are not just tested globally as part of the representations of family-level relationships.

First, SEM analysis of children’s negative-disciplinary father representations indicated that paternal distress was relatively stable (B = .662, p < .001), and paternal distress at 5 years was a significant predictor of children’s negative-disciplinary representation of fathers (B = .007, p < .01). Child verbal and cognitive ability were not predictive of children’s negative-disciplinary father representations (B = −.005, p > .05; B = .000, p > .05), therefore, child verbal and cognitive ability at age 4 years were eliminated from the model. However, the covariate child sex was significantly related to such representation (B = .033, p < .001); boys expressed more negative-disciplinary father representations than girls did. The indirect effect of paternal distress at 14 months on children’s representations of negative-disciplinary fathers at 5 years via paternal distress at 5 years was significantly different from zero according to the Sobel test (Z = 2.16, p < .05). The fit of the structural model was good after adjusting the chi-square values by the I-NULL and I-SAT model (χ2[16] = 8.906, p > .10; CFI = .981; RMSEA = .037).

Second, the results of children’s family conflict representations showed that paternal distress at 5 years was associated with children’s family conflict representations (B = .011, p < .05). Child verbal ability was not predictive of children’s representations (B = −.007, p > .05) but, the paths from child cognitive ability and sex to children’s family conflict representations were significant (B = .001, p < .05; B = .048, p < .001). Therefore, child verbal ability at age 4 years was removed from the model. The indirect effect of paternal distress at 14 months on children’s representations of family conflict at 5 years through paternal distress at 5 years was significantly different from zero according to the Sobel test (Z = 2.04, p < .05). The test of the structural model produced an adequate fit of the model to the data after the chi-square values were adjusted by the I-NULL and I-SAT model (χ2[53] = 99.599, p < .05; CFI = .960; RMSEA = .053).

Third, SEM results demonstrated that paternal distress was relatively stable over time, but not a significant predictor of children’s positive representation of fathers (B = .007, p > .05) or children’s representations of family harmony (B = .003, p > .05). Therefore, we eliminated positive father representations and family harmony from all future models.

Model 3: Test of the Full Model

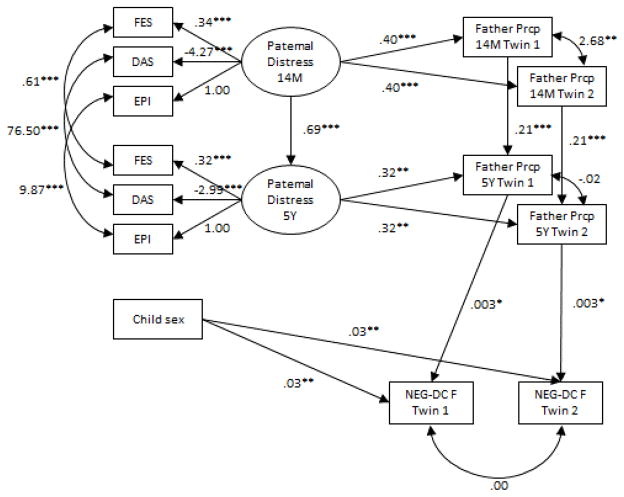

Finally, two full structural models were tested to assess possible mediation effects of father temperament ratings. First, the results from the model predicting children’s negative-disciplinary representations of fathers indicated that both paternal distress (14 to 5 years, B= .694, p < .001) and father ratings of child temperament (14 to 5 years, B= .208, p < .001) were consistently stable over time. Paternal distress predicted father ratings of child temperament at 14 months and 5 years of child age (B= .403, p < .001; B= .325, p < .01). Father ratings of child negative emotionality at age 5 years were directly associated with children’s representations of negative fathers at 5 years (B = .003, p < .05). Child sex was predictive of children’s representations of negative fathers at 5 years (B= .034, p < .001; Figure 1), meaning boys showed more negative father representations, but child cognitive ability was not predictive of children’s representations of negative-disciplinary fathers (B= .000, p > .05). The adjusted structural model fit was good (χ2[33] = 32.518, p > .10; CFI = .999; RMSEA = .007). In this model, two possible pathways to test mediation effects were tried. The effect of paternal distress at age 14 months on children’s representations of negative fathers at 5 years was tested as mediated by fathers’ temperament ratings of the child at age 14 months through 5 years, and this path was significantly different from zero (Z = 2.10, p < .05). Also, the indirect effect of paternal distress at age 14 months on children’s representations of negative fathers at 5 years via paternal distress at age 5 years and fathers’ temperament ratings of the child at age 5 years also was significantly different from zero based on the Sobel test (Z = 2.02, p < .05).

Figure 1. Final Model of Children’s Representations of Negative Fathers.

FES = Family Environment Scales, DAS = Dyadic Adjustment Scale, EPI = Eysenck Personality Inventory, Father Prcp = Paternal Perception of child emotionality, NEG-DC F = Negative-Disciplinary father representation.

†p < .10. *p < .05. **p<.01. ***p < .001.

Note. Unstandardized Path Values are shown.

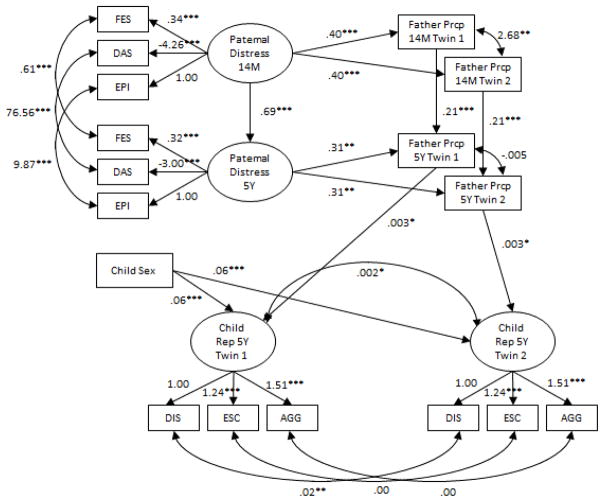

The same procedures again were performed for the model predicting children’s representations of family conflict. As in the previous results, paternal distress and father ratings of child temperament were stable across the different time points at p < .001. Paternal distress was associated with father ratings of child temperament at 1 and 5 years (B= .403, p < .001; B= .311, p < .01). The direct path between father ratings of negative emotionality in child temperament at age 5 and children’s representations of family conflict (B = .004, p < .05) at age 5 was significant. Also, child sex and cognitive abilities were predictive of children’s representations of family conflict (B = .049, p < .001; B = .004, p < .05). The adjusted structural model fit was good; χ2[86] = 135.894, p < .05; CFI = .960; RMSEA = .043. We again tested the same possible mediation paths as in the negative-disciplinary father representation model. The indirect effect of paternal distress at age 14 months on children’s representations at 5 years via fathers’ temperament ratings of the child at age 14 months through 5 years was marginally different from zero based on the Sobel test (Z = 1.66, p < .10).

To estimate a better fitting model and test the significance of the indirect effect, we modified the model predicting children’s representations of family conflict. To improve the model, a modified CFA with the latent variable of children’s representations of family conflict was tested without the observed variable of anger because this indicator was non-significant in the full model. Also, child cognitive ability, which showed a relatively weak association with child representations, was removed from the model. All paths in the revised model were significant from paternal distress at child age 14 months to children’s representations of family conflict at p < .05 (Figure 2). The adjusted model fit was improved (χ2[56] = 54.68, p > .05; CFI = .999; RMSEA = .009). Results of the Sobel test suggested that the association between paternal distress at child age 14 months and children’s representations of family conflict at child age 5 years was significantly mediated by paternal perceptions of child temperament at 14 months and 5 years (Z = 2.11, p <. 05), as well as paternal distress at age 5 and paternal perception of children’s temperament at 5 years (Z = 2.00, p < .05).

Figure 2. Final Model of Children’s Representations of Family Conflict.

FES = Family Environment Scales, DAS = Dyadic Adjustment Scale, EPI = Eysenck Personality Inventory, Father Prcp = Paternal Perception of child emotionality, Child Rep = Children’s Representations, AGG = Aggression, ESC = Escalation of interpersonal conflict, DIS = Distress.

†p < .10. *p < .05. **p<.01. ***p < .001.

Note. Unstandardized Path Values are shown.

Discussion

The first model tested whether paternal distress over time would be associated with fathers’ representations of children’s negative emotionality in temperament, and our model was supported. At each time point, paternal distress was associated significantly with father ratings of each twin’s emotionality, and ratings of child emotionality showed considerable stability from ages one to five years. This is consistent with earlier literature and propositions from attachment theory suggesting that parental psychological states carry over not only into parenting behaviors (Trapolini, Ungerer, & McMahon, 2008), but also into parents’ representations of their children’s behavior, such that distressed parents view their children as also being more distressed (Benoit, Parker, & Zeanah, 1997; Milgrom & McCloud, 1996). Others also suggest that parent reports reflect both a biased/subjective as well as a reliable/objective view of the child’s temperament (Bates, Schermerhorn, & Goodnight, 2010). Indeed, temperament ratings within twin dyads were significantly correlated only at 14 months. By 5 years, twin ratings were not significantly correlated suggesting children’s individuality influencing fathers’ experience of the children.

Of concern when parents have a generally negative world view such that they “see” their own problems and tendencies reflected in their children’s behavior, are potential epigenetic processes promoting increasingly negative emotionality in the child. That is, fathers contribute both genetic and environmental sources of influence on their children that tend to amplify these traits in each other. In the present study, this was true not only for fathers’ ratings of one child, but for his ratings of both twin children, further supporting the existence of a generalized “spillover” of paternal distress into ratings of child temperament. Other research has demonstrated substantial links between negative emotionality and parent reports of behavior problems (e.g., Rende, 1993; Schmitz et al., 1999), leading many to be concerned about early appearing negative reports of child temperament and its possible foreshadowing of future problematic child behavior.

Our second model tested whether children’s family harmony and conflict representations and representations of fathers as positive or negative-disciplinary would be predicted by paternal distress assessed at ages 14 months and 5 years. Father distress, as assessed by indicators of personality, marital adjustment, and conflict in the family, showed strong stability over time. There were significant associations with children’s representations of negative-disciplinary fathers and conflicted families, but not positive representations of fathers or family harmony. Consistent with previous literature regarding mothers, the present study found that children represented families and fathers more negatively when their fathers exhibited higher signs of distress (Oppenheim, Emde, & Warren, 1997; Toth, Rogosch, Sturge-Apple, & Cicchetti, 2009). Importantly, however, children’s positive representations were not decreased concurrently with the increase in negative representations. As such, there appears to be a specific influence of fathers’ negativity (distress) on what children expressed about fathers’ negative-disciplinary roles and family relationships, including father, mother, and sibling contributions to conflict. Positive family representations were relatively more frequently represented by children and at this age, positivity may dominate the child’s experience even when parents themselves experience more distress in their family life. This emphasizes the need to investigate the influence of parents (and particularly fathers) on their children in more nuanced and complex ways and for conceptualizing positivity and negativity as not simply opposite ends of a single continuum. Additionally, associations between predictors and outcomes should be tested in ways that allow for models to be estimated concurrently, rather than running separate models for positive and negative outcomes (e.g., SEM), which might mask potential overlapping effects between variables and whether one variable is “driving” the findings.

In earlier work, elevated maternal distress was associated with less frequent positive and disciplinary representations and elevated negative representations when children’s representations of mothers were examined one at a time (Oppenheim, et al, 1997). The present findings are important in that they not only confirm the previous literature about the impact of parental distress, but also extend research findings regarding mothers’ distress to fathers. In the present study, negative father representations were combined with father disciplinary representations because they were relatively infrequent, and the resulting construct was positively associated with paternal self-reports of distress.

The ways in which paternal characteristics affect family processes and children, such as via perceptions of the child’s temperament, have received little empirical attention. The negative emotionality subscale provides an interesting parallel to the adult neuroticism dimension of personality, reflecting a direct measure of the father’s view of the child’s distress-prone qualities. This is a potentially important bridge between his own distress and a developing negative affective bias of the child. Given the growing body of literature substantiating the significant influence fathers have on children (e.g., Lamb, 2010; Marsiglio, Amato, Day, & Lamb, 2000), understanding the full emotional spectrum of paternal influences and mechanisms is important.

In the third and final model, we combined Models 1 and 2 and tested whether fathers’ ratings of child temperament would mediate the association between paternal distress and children’s negative-disciplinary representations of fathers and family conflict; this was supported. After all insignificant paths were removed, there also were indirect paths between paternal distress and children’s negative-disciplinary representations of fathers and family conflict, via fathers’ ratings of child temperament.

Parent ratings of temperament, specifically emotionality, have infrequently been studied in relation to children’s narrative representations. One study by Goldwyn, Stanley, Smith, & Green (2000) found higher negative emotionality ratings on the EAS were related to children’s over-arousal during story-telling. A second paper examined children’s anxiety-related, negative expectations of story resolution with parent ratings of shyness and fearfulness and found no association (Warren, Emde, & Sroufe, 2000). In the current study, father ratings of children’s negative emotionality were associated with children’s negative-disciplinary representations of fathers and conflictual family relations. This finding suggests that, in addition to having a direct influence, paternal distress influences children’s views of their fathers at least partially because paternal distress first has influenced fathers’ views of their children. More distressed fathers view their children as having higher levels of negative emotionality, and this, in turn, is associated with children having more negative representations of their fathers. This finding is strengthened further by the fact that this was a longitudinal investigation; ratings of child temperament were first assessed in late infancy and were moderately stable over time. It is significant that father distress and father ratings of temperament predicted not only children’s views of fathers, but children’s views of the entire family. As such, the distress experienced by fathers in families influenced children’s family experiences in broad ways, both directly and indirectly. This further emphasizes the need to account for fathers when it comes not only to research, but also family- and child-oriented policy, programs, and interventions that support parenting in the child’s earliest years.

Based on previous research on children’s narratives (Page & Bretherton, 2001; von Klitzing, Kelsay, Emde, Robinson, & Schmitz, 2000), gender differences in children’s representations of negative-disciplinary fathers and family conflict have been found. We included child sex in our models to account for this difference and indeed, observed the more frequent inclusion of negative-disciplinary fathers themes among boys compared to girls, as well as more frequent family conflict representations.

There are several limitations of this work. This is a secondary analysis of a large longitudinal study and our measure of distress is not a standardized measure of “psychological distress”. Rather, we drew on three measures that included distress experienced in one’s personality, family climate, and the marital relationship. Including contexts of family life might allow us to capture a broader sense of the levels of distress in the child’s relational environment; seeing them through the father’s experience is a novel approach to estimating family processes. In addition, we did not have a measure of fathers’ parenting behavior or father-child interaction that might confirm whether these sources of distress enter into the behavioral aspects of their relationship, as suggested by other research in this area (Belsky, 1984). Finally, the sample was comprised solely of families with same-sex twin pairs and although other research indicates there may be unique stressors involved in raising same-age siblings (Chang, 1990; Thorpe, et al, 1991), our analysis did not take that into account. We assumed family and developmental processes that are generalized and not unique to twins given their good health status at birth and parents’ education levels. Our future work also will examine the role of heritability in family experiences with distress as it may be an important mediator for father-child (and mother-child) relationships.

Overall, this study expands our knowledge about the ways in which parental distress influences children’s views of their families by confirming the influence of fathers’ distress. Also, positive and negative representations of fathers and family were impacted differentially by paternal distress and father ratings of child temperament, emphasizing the need for greater specificity and concurrent examination of positive and negative outcomes. Of note, children’s positive representations were not diminished at higher levels of paternal distress, suggesting that children may draw on these positive narrative features to build resilience to higher levels of distress in their families. Future studies should expand our understanding of the quality of father-child relationships, how they are affected by many sources of paternal distress, and their emotional-behavioral impacts on children.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation and the National Institute for Mental Health grants HD010333 and HD050346.

References

- Bartholomew K, Horowitz LM. Attachment styles among young adults: A test of a four-category model. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1991;61:226–244. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.61.2.226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bates JE, Schermerhorn AC, Goodnight JA. Temperament and personality through the lifespan. In: Freund AM, Lamb ME, editors. Social and emotional development across the life span: Vol. 2, Handbook of life-span development. NJ: John Wiley & Sons; 2010. pp. 208–253. [Google Scholar]

- Belsky J. The determinants of parenting: A process model. Child Development. 1984;55:83–98. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1984.tb00275.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belsky J, Crnic K, Woodworth S. Personality and parenting: Exploring the mediating role of transient mood and daily hassles. Journal of Personality. 1995;63:905–929. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6494.1995.tb00320.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benoit D, Parker KCH, Zeanah CH. Mothers’ representations of their infants assessed prenatally: Stability and association with infants’ attachment classifications. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 1997;38:307–313. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.1997.tb01515.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benoit D, Zeanah CH, Parker KCH, Nicholson E, Coolbear J. “Working Model of the Child Interview”: Infant clinical status related to maternal perceptions. Infant Mental Health Journal. 1997;18:107–121. [Google Scholar]

- Bolger N, DeLongis A, Kessler RC, Wethington E. The contagion of stress across multiple roles. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1989;51:175–183. [Google Scholar]

- Bolger N, Shilling EA. Personality and the problems of everyday life: The role of neuroticism in exposure and reactivity to daily stressors. Journal of Personality. 1991;59(3):355–386. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6494.1991.tb00253.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bost KK, Choi E, Wong MS. Narrative structure and emotional references in parent-child reminiscing: associations with child gender, temperament, and the quality of parent-child interactions. Early Child Development and Care. 2010;180:129–156. [Google Scholar]

- Bowlby J. Attachment and loss: Vol. I. Attachment. 2. New York: Basic Books; 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Bretherton I. Attachment theory: Retrospect and prospect. Growing points in attachment theory and research. 1985;49:3–35. [Google Scholar]

- Bretherton I. New perspectives on attachment relations: Security, communication and internal working models. In: Osofsky J, editor. Handbook of infant development. 2. New York: Wiley; 1987. pp. 1061–1100. [Google Scholar]

- Bretherton I. Communication patterns, internal working models, and the intergenerational transmission of attachment relationships. Infant Mental Health Journal. 1990;11:237–252. [Google Scholar]

- Bretherton I. Fathers in attachment theory and research: a review. Early Child Development and Care. 2010;180(1–2):9–23. [Google Scholar]

- Bretherton I, Biringen Z, Ridgeway D, Maslin C, Sherman M. Attachment: The parental perspective. Infant Mental Health Journal. 1989;10:203–221. [Google Scholar]

- Bretherton I, Oppenheim D, Buchsbaum H, Emde RN the MacArthur Narrative Group. MacArthur Story-Stem Battery. 1990 Unpublished manual. [Google Scholar]

- Bretherton I, Ridgeway D, Cassidy J. Assessing internal working models of the attachment relationship: An attachment story completion task for 3-year-olds. In: Greenberg MT, Cicchetti D, Cummings EM, editors. Attachment in the preschool years: Theory, research, and intervention. Chicago: University ofChicago Press; 1990. pp. 273–308. [Google Scholar]

- Buss AH, Plomin R. A temperament theory of personality development. Oxford England: Wiley-Interscience; 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Cassidy J, Shaver PR. Handbook of attachment: Theory, research, and clinical applications. NY: Guilford; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Chang C. Raising twin babies and problems in the family. Acta Gen eticae Medicae Gemellologiae. 1990;39:501–505. doi: 10.1017/s0001566000003743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chess S, Thomas A. Temperament: Theory and practice. New York: Brunner/Mazel; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Clark LA, Kochanska G, Ready R. Mothers’ personality and its interaction with child temperament as predictors of parenting behaviour. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2000;79:274–285. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.79.2.274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colpin H, De Munter A, Nys K, Vandemeulebroecke L. Parenting stress and psychosocial well-being among parents with twins conceived naturally or by reproductive technology. Human Reproduction. 1999;14(12):3133–3137. doi: 10.1093/humrep/14.12.3133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colpin H, De Munter A, Nys K, Vandemeulebroecke L. Pre- and postnatal determinants of parenting stress in mothers of one year old twins. Marriage & Family Review. 2000;30:99–107. [Google Scholar]

- Costa PT, McCrae RR. Influence of extraversion and neuroticism on subjective well-being: Happy and unhappy people. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1980;38:668–678. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.38.4.668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crockenberg SB. Are temperamental differences in babies associated with predictable differences in care giving? New Directions for Child and Adolescent Development. 1986;31:53–73. [Google Scholar]

- Daniels D, Plomin R, Greenhalgh J. Correlates of difficult temperament in infancy. Child Development. 1984;55(4):1184–1194. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Easterbrooks MA, Emde RN. Marital and parent-child relationships: The role of affect in the family system. In: Hinde RA, Stevenson-Hinde J, editors. Relationships within families: Mutual influences. Oxford: Claredon; 1988. pp. 83–103. [Google Scholar]

- Emde RN, Hewitt JK. Infancy to early childhood: Genetic and environmental influences on developmental change. New York: Oxford University Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Enders CK. The impact of nonnormality on fill information maximum-likelihood estimation for structural equation models with missing data. Psychological Methods. 2001;6(4):352–370. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eysenck HJ, Eysenck SBG. Personality: Structure and measurement. London: Routledge and K. Paul; 1969. [Google Scholar]

- Fincham FD, Beach SRH, Harold GT, Osborne LN. Marital satisfaction and depression: Different causal relationships for men and women? Psychological Science. 1997;8:351–357. [Google Scholar]

- Fivush R, Brotman MA, Buckner JP, Goodman SH. Gender differences in parent-child emotion narratives. Sex Roles. 2000;42:233–253. [Google Scholar]

- Foster CE, Webster MC, Weissman MM, Pilowsky DJ, Wickramaratne PJ, Rush JA, et al. Course and severity of maternal depression: Associations with family functioning and child adjustment. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2008;37:906–916. doi: 10.1007/s10964-007-9216-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freeman H, Newland LA, Coyl DD. New directions in father attachment. Early Child Development and Care. 2010;180(1–2):1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Goldwyn R, Stanley C, Smith V, Green J. The Manchester Child Attachment Task: relationship with parental AAI, SAT and child behaviour. Attachment & Human Development. 2000;2(1):71–84. doi: 10.1080/146167300361327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodman LA. On the exact variance of products. Journal of the American Statistical Association. 1960;55:708–713. [Google Scholar]

- Gotlib IH. Interpersonal and cognitive aspects of depression. Current Directions in Psychological Science. 1992;1:149–154. [Google Scholar]

- Holmberg J, Robinson J, Wiener P, Corbitt-Price- J. Using narratives to assess competencies and risks in young children: Experiences with high risk and normal populations. Infant Mental Health Journal. 2007;28:647–666. doi: 10.1002/imhj.20158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holt-Lunstad J, Birmingham W, Jones BQ. Is there something unique about marriage? The relative impact of marital status, relationship quality, and network social support on ambulatory blood pressure and mental health. Annals of Behavioral Medicine. 2008;35(2):239–244. doi: 10.1007/s12160-008-9018-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kenny DA, Kashy DA, Cook WL. The analysis of dyadic data. New York: Guilford Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Kline RB. Principles and practice of structural equation modeling. 2. New York: Guilford Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Kochanska G. Mother-child relationship, child fearfulness, and emerging attachment: A short-term longitudinal study. Developmental Psychology. 1998;34:480–490. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.34.3.480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kronmuller KT, Backenstrass M, Victor D, Postelnicu I, Schenkenbach C, Joest K, Fiedler P, Mundt C. Quality of marital relationship and depression: Results of a 10-year prospective follow-up study. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2011;128:64–71. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2010.06.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamb ME. The role of the father in child development. 5. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Lange AL. Coping ability at mid-life in relation to genetic and environmental influences at adolescence: A follow-up of Swedish twins from adolescence to mid-life. Twin Research. 2003;6(4):344–350. doi: 10.1375/136905203322296737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levy-Schiff R. Individual and contextual correlates of marital change across the transition to parenthood. Developmental Psychology. 1994;30:591–601. [Google Scholar]

- Little RJA. A test of missing completely at random for multivariate data with missing values. Journal of the American Statistical Association. 1988;83:1198–1202. [Google Scholar]

- Lucassen N, Van IJzendoor MH, Volling B, Thamer A, Bakermans-Kranenburg MJ, Verhulst FC, Lambregtse-Van den Berg MP, Tiemeier H. The association between paternal sensitivity and infant-father attachment security: A meta-analysis of three decades of research. Journal of Family Psychology. 2011;25:968–992. doi: 10.1037/a0025855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lytton H, Singh JK, Gallagher L. Parenting twins. In: Bornstein MH, editor. Handbook of Parenting, Vol 1: Children and Parenting. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum; 1995. pp. 185–208. [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon DP, Lockwood CM, Hoffman JM, West SG, Sheets V. A comparison of methods to test mediation and other intervening variable effects. Psychological Methods. 2002;7:83–104. doi: 10.1037/1082-989x.7.1.83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Main M, Kaplan N, Cassidy J. Security in infancy, childhood and adulthood: A move to the level of representation. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development. 1985;50(1/2):66–104. [Google Scholar]

- Marcussen K. Explaining differences in mental health between married and cohabiting individuals. Social Psychology Quarterly. 2005;68(3):239–257. [Google Scholar]

- Marsiglio W, Amato P, Day RD, Lamb ME. Scholarship on fatherhood in the 1990s and beyond. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2000;62(4):1173–1191. [Google Scholar]

- McCabe SG, Gotlib IH. Interactions of couples with and without a depressed spouse: Self-report and observations of problem-solving situations. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships. 1993;10:589–599. [Google Scholar]

- Mebert CJ. Stability and change in parents’ perceptions of infant temperament: Early pregnancy to 13.5 months postpartum. Infant Behavior and Development. 1989;12:237–244. [Google Scholar]

- Mebert CJ. Dimensions of subjectivity in parents’ ratings of infant temperament. Child Development. 1991;62(2):352–361. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michiels D, Grietens H, Onghena P, Kuppens S. Perceptions of maternal and paternal attachment security in middle childhood: Links with positive parental affection and psychosocial adjustment. Early Child Development and Care. 2010;180:211–225. [Google Scholar]

- Milgrom J, McCloud P. Parenting stress and postnatal depression. Stress Medicine. 1996;12(3):177–186. [Google Scholar]

- Moos RH. Conceptual and empirical approaches to developing family-based assessment procedures: Resolving the case of the Family Environment Scale. Family Process. 1990;29(2):199–208. doi: 10.1111/j.1545-5300.1990.00199.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moos RH, Moos BS. Family Environmental Scale manual. Palo Alto, CA: Consulting Psychologists Press; 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Muniz J, Garcia-Cueto E, Lozano LM. Item format and the psychometric properties of the Eysenck Personality Questionnaire. Personality and Individual Differences. 2005;38:61–69. [Google Scholar]

- Newland LA, Coyl DD, Freeman H. Predicting preschools’ attachment security from fathers’ involvement, internal working models, and use of social support. Early Child Development and Care. 2008;178(7–8):785–801. [Google Scholar]

- Olsen AJ, Kenny DA. Structural equation modeling with interchangeable dyads. Psychological Methods. 2006;11(2):127–141. doi: 10.1037/1082-989X.11.2.127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]