Abstract

Imatinib (Gleevec) is the effective therapy for BCR-ABL positive CML patients. Point mutations have been detected in ATP-binding domain of ABL gene which disturbs the binding of Gleevec to this target leading to resistance. Detection of mutations is helpful in clinical management of imatinib resistance. We established a very sensitive (ASO) PCR to detect mutations in an imatinib-resistant CML patient. Mutations C944T and T1052C were detected which cause complete partial imatinib resistance, respectively. This is the first report of multiple point mutations conferring primary imatinib resistance in same patient at the same time. Understanding the biological reasons of primary imatinib resistance is one of the emerging issues of pharmacogenomics and will be helpful in understanding primary resistance of molecularly-targeted cancer therapies. It will also be of great utilization in clinical management of imatinib resistance. Moreover, this ASO-PCR assay is very effective in detecting mutations related to imatinib resistance.

Keywords: Leukemia, Myeloid, Chronic; Fusion Proteins, bcr-abl; ATP-Binding Cassette Transporters

Introduction

Chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) is a stem cell disorder (1). This is a myeloproliferative disease characterized by marked increase in granulocytes, marked bone marrow hyperplasia and spleenomegaly (2). The symptoms which appear in initial phase are non-specific including fever, anaemia, fatigue, weight loss, weakness, and others (3). CML primarily affects the adults between 25-60 years of age and accounts for 15-20% of all leukemia cases (4).

CML is associated with presence of Philadelphia (Ph) chromosome detectable microscopically which results from balanced chromosomal translocation t (9:22) (q34; q11), that is, translocation of proto-oncogene ABL from chromosome 9 to BCR gene at Chromosome 22 (5). BCR-ABL translocation is common in 95% of patients and Ph chromosome is found in all dividing multipotent stem cells (5). BCR-ABL fusion gene formed as a result of this translocation encodes a protein which has tyrosine kinase and oncogenic activity (6).

Median survival for CML patients is 3-8 years after clinical manifestation of the disease and physicians have very little time for treatment of this fatal disease (7). Hydroxyurea and interferon are first-line treatment for CML patients but usually patients show resistant to these therapies (8). STI 571 commonly called as Imatinib or Gleevec is currently the most specific drug for CML patients and is regarded as very effective therapy for CML patients (9). This drug binds to ATP -binding site of tyrosine kinase domain in bcr-abl protein, a protein which triggers the carcinogenesis pathway leading to manifestation of the disease (10). Thus, by occupying and blocking the ATP binding site, it stops the signal transduction leading to onset of Leukemia (10). However, a considerable number of patients have been reported to show resistance to Gleevec, leading to relapses (11). Resistance against Gleevec has been attributed to mutations in the ATP–binding site of tyrosine-protein kinase domain of the BCR-ABL gene which lead to conformational changes in bcr-abl protein resulting in impairment of Gleevec binding (11-14). Many BCR-ABL single base pair mutations have been found in Gleevec resistant CML patients (15). It has been reported that different mutations in tyrosine-protein kinase domain of the BCR-ABL transcript lead to different degree of the drug resistance, depending upon the nature and location of the mutations (16). Some of the mutations lead to moderate resistance and dose escalation can efficiently overcome Gleevec resistance in these cases (17). On the other hand, some of the mutations lead to complete drug resistance (16-18). Under such circumstances, combination therapies with Gleevec or use of some substitution therapy have been reported to manage this resistance (19, 20).

We checked mutations in ABL gene ATP-binding domain of a CML patient who had been on oral dose of 400mg/day of Gleevec for nine months. Patient had no hematological, cytogenetic or molecular response to Gleevec. A very sensitive ASO-PCR method (21) was used to detect three mutations namely C944T, T932C and T1052C. Interestingly, we found two mutations in this patient: C944T mutation causing threonine to isoleucine substitution at amino acid 311 and T1052C mutation leading to amino acid substitution from methionine to leucine at position 351. This is the first report of double mutation in ABL gene ATP-binding domain of a Gleevec resistance CML patient. This new finding and its biological and clinical implications are discussed.

Materials and Methods

Patient’s inclusion criteria: A CML patient with oral dose of 400 mg/day for nine months of Gleevec who has no hematological, cytogenetic and molecular response to drug was investigated for ABL gene ATP-binding domain mutations responsible for Gleevec resistance. Blood sample was taken from patient in EDTA. Consent from patient was obtained for this study.

DNA Extraction: Genomic DNA was extracted from patient’s blood using the method described by Sambrook et al. in 1989 (22) with little modifications and optimization. Briefly:

One ml of blood was taken. It was mixed with 9 ml of Buffer A (Sucrose 10.95g, 1M Tris HCl 1ml, 1M MgCl2 500 μl and 1 ml of Triton per 100 ml of buffer ), incubated on ice for 2 minutes and spun at 1500 rpm for 15 minutes at 4°C.

Pink pellet of nuclei was resuspended in 320 μl of cold Buffer B (25 ml of EDTA pH 8, 20 ml of 5M NaCl per 100 ml of buffer). Thirty two μl of 10% SDS and 3.5 μl of Proteinase-K (10mg/ml) were added. The mixture was subjected to shaking incubation at 37°C overnight.

An equal volume of buffer-equilibrated phenol was added and mixed on ice for 10-15 minutes. It was centrifuged at 2500 rpm for 15 minutes at 4°C.

Supernatant was taken, an equal volume of chloroform: isoamyl alcohol (24:1) was added and mixed gently at room temperature for 15-30 minutes. Phases were separated by centrifugation at 2500 rpm for 15 minutes at 4°C.

Supernatant was taken, 1/10 volume of 3M sodium acetate and 1.5 volume of 100% isopropanol was added. DNA was precipitated.

Pellet was obtained by centrifugation at 14,000 rpm for 20-30 minutes at room temperature. It was washed with 70% ethanol and air-dried.

Pellet was dissolved in Tris EDTA buffer, DNA quantity estimated spectrophotometrically and stored at -20°C.

Allele-specific oligonucleotide (ASO) PCR: Allele Specific Oligonucleotides (ASO) and Normal Primers (NP): ASO-PCR assay described by Catherine Roche-Lestienne et al. (2002) (21) was used for detection of three mutations of ABL gene ATP-binding domain namely C944T, T932C and T1052C. DNA was amplified with normal primer (NP) or mutation specific forward primers (ASO) and a common reverse primer. The identitities and sequences of the primers are given in Table 1.

Table 1.

Identities and sequences of Primers used in ASO-PCR (Difference between normal and Allele (mutation) Specific Oligonucleotides indicated).

| Sr. # | Mutation | Primer identity | Primer type | Polarity | Primer sequence (5/-3/) |

| A1 | NP | Forward | GCC CCC GTT CTA TAT CAT CAC | ||

| 1 | C944T | A2 | ASO | Forward | GCC CCC GTT CTA TAT CAT CAC |

| R1 | Common | Reverse | GGA TGA AGT TTT TCT TCT CCA | ||

| B1 | NP | Forward | CAC CCG GGA GCC CCC GT | ||

| 2 | T932C | B2 | ASO | Forward | CAC CCG GGA GCC CCC GC |

| R4 | Common | Reverse | CCC CTA CCT GTG GAT GAA GT | ||

| C1 | NP | Forward | CCA CTC AGA TCT CGT CAG CCA T | ||

| 3 | T1052C | C2 | ASO | Forward | CCA CTC AGA TCT CGT CAG CCA C |

| R5 | Common | Reverse | GCC CTG AGA CCT CCT AGG CT | ||

PCR Mix preparation: A 50 μl PCR reaction was performed containing 3μl of DNA, 10X PCR buffer (Fermentas, USA), 1.5 mM MgCl2, 300 M each of dATP, dGTP, dCTP and dTTP, 1.5 U Taq DNA polymerase (Fermentas, USA) and 25 pM each of forward and reverse primers. A negative control and a control from a clinically-declared healthy person with no Philadelphia positive leukemia were also included in the study.

PCR Thermal Profile: Thermo cycling conditions for this ASO-PCR conditions were 12 minutes at 94°C followed by 35 cycles of denaturation at 95°C for 1 minute, annealing at 64°C (for mutation 1 and 2) or 68°C (for mutation 3) for 1 minute and extension at 72°C for 1 minute, followed by a final extension at 72°C for 5 minutes.

Gel Electrophoresis: Amplified products from ASO-PCR were electrophorised at 1.5% gel and visualized and analysed after staining with 3% ethidium bromide.

Results

Analysis of Mutation C944T

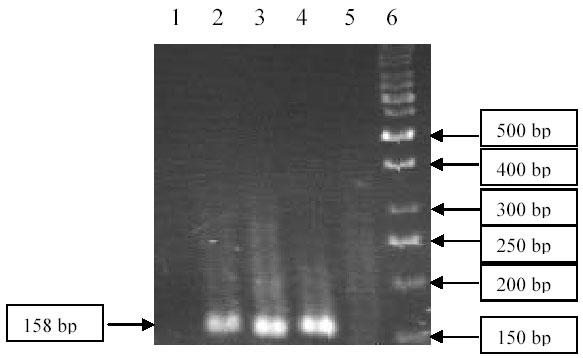

Cytosine to Thymine mutation at position 944 of ABL gene was checked by ASO-PCR. Patient DNA and DNA from a healthy control were amplified with Allele-specific oligonucleotide as well as normal primer to give a PCR product of 158 bp. Although both patient and healthy control DNA yielded specific bands with normal forward primer, PCR product was observed only for patient when amplified using mutation specific primer (Fig 1). So, mutation C944T was found in this patient.

Fig. 1. Detection of Mutation C944T Mutation by ASO–PCR.

Lane 1: Negative control, Lane 2: Patient’s DNA amplified with normal primer, Lane 3: Patient’s DNA amplified with mutation specific primer (ASO), Lane 4: Control DNA amplified with normal primer, Lane 5: Control DNA amplified with mutation specific primer (ASO), Lane 6: DNA ladder (50 bp) Fermentas.

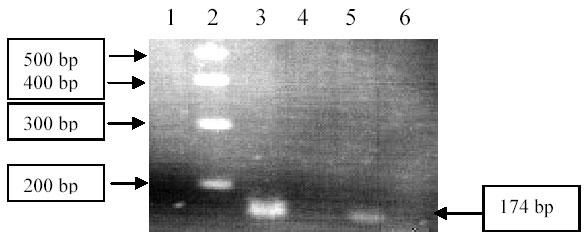

Analysis of Mutation T932C

Thymine to cytosine substitution at position 932 of ABL gene of Gleevec-resistance CML patient was checked by ASO-PCR. Patient DNA and DNA from a healthy control were amplified with allele-specific oligonucleotide (mutation specific primer) as well as normal primer to give a PCR product of 174 bp (Fig. 2). Specific band using normal primer was detected on gel for patient as well as healthy control but no PCR product was observed for patient DNA when amplified with mutation specific primer (ASO).

Fig. 2. Detection of Mutation T932C Mutation by ASO-PCR.

Lane 1: Negative control, Lane 2: DNA ladder (100 bp) Fermentas, Lane 3: Control DNA amplified with normal primer, Lane 4: Control DNA amplified with mutation specific primer (ASO), Lane 5: Patient’s DNA amplified with normal primer, Lane 6: Patient’s DNA amplified with mutation specific primer (ASO).

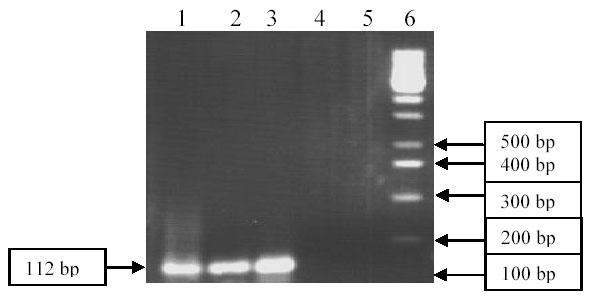

Analysis of Mutation T1052C

This mutation also confers Gleevec resistance in CML patients. For checking this thymine to cytosine substitution at position 1052 of ABL gene in Gleevec-resistance CML patient, ASO-PCR was performed using mutation specific primer (Allele -specific oligonucleotide) as well as normal primer to give a PCR product of 112 bp. Although gel electrophoresis showed specific amplification both for patient and healthy control, 112 bp ASO -PCR product was observed only for patient (Fig. 3). It is inferred that mutation C1052T mutation is also involved in this patient in conferring Gleevec resistance.

Fig. 3. Detection of Mutation T1052C by ASO–PCR.

Lane 1: Patient’s DNA amplified with normal primer, Lane 2: Patient’s DNA amplified with mutation specific primer (ASO), Lane 3: Control DNA amplified with normal primer, Lane 4: Control DNA amplified with mutation specific primer (ASO), Lane 5: Negative control, Lane 6: DNA ladder (100 bp) Fermentas).

On the basis of our results, we conclude that two mutations are responsible for primary Gleevec resistance in the CML patient under study. We also conclude that this ASO-PCR is very effective and sensitive to detect point mutations conferring imatinib resistance in CML patients.

Discussion

CML is a very fatal disease which is very difficult to treat (23). Patients usually resist the chemotherapy like hydroxyurea and interferon-á (24). In recent years, Gleevec has fascinated the physicians, clinicians, patients and researchers by its high effectiveness against BCRABL positive CML patients (25). As it stops the oncogenic activity of bcr-abl onco-protein by binding to its ATP-binding site in kinase domain, it has fewer side effects than interferon and is thus well-tolerated (26). It binds to some amino acids in ATP-binding domain by making hydrogen bonds (12). Recently it was found that some mutations in ABL gene ATP-binding domain lead to conformational changes in bcr-abl oncoprotein, thus resulting in impairment of Gleevec binding and leading to clinical resistance (27). Some mutations cause complete Gleevec resistance as they completely stop the Gleevec binding to its target while other mutations only affect this binding partially, leading to only moderate resistance to this drug (14, 18, 28). Thus, detection of mutations associated with Gleevec resistance is of a considerable clinical impact.

Allele specific oligonucleotide (ASO) PCR is a very specific and sensitive technique for detection of known mutations (29). This method is even sensitive than mutation detection by sequencing of ABL ATP-binding domain (30) because DNA sequencing can only useful for point mutation detection when proportion of mutated cells is more than 30% (21). In cases where number of mutated cells is less than 30% of the total cells in patient’s sample, at least 10 independent clones from the patient must be analysed for mutation detection which is quite costly and time consuming (21). On the other hand, ASO-PCR is comparatively more sensitive, specific, very economical and quick method for detection of mutations (31). The ASO-PCR established by us is able to detect one mutated, Gleevec resistant cell out of 10,000 normal cells (21).

In present study, we found two mutations in a Gleevec-resistant CML patient by ASO-PCR method. It is the first report of multiple mutations in a Gleevec resistant CML patient. A Thymine to cytosine mutation at position 1052 of ABL gene was detected. This mutation leads to amino acid substitution from Methionine to Threonine at position 351 of ABL ATP binding domain (18). This mutation only partially impairs the binding of Gleevec to its target and thus leads to partial drug resistance (21). This mutation has previously been reported (18). It has been authoritatively documented that partial Gleevec resistance can be actively overcome by dose escalation of Gleevec from 600-1600mg/day (32). On the other hand, a cytosine to thymine mutation at ABL gene position 944 was detected which causes threonine to isoleucine amino acid substitution at amino acid position 315 in ATP-binding domain of bcr-abl oncoprotein. This mutation has already been reported by various authors like (12-14, 18, 33). It has been determined on the basis of crystal structure of abl kinase domain that Threonine 315 is among those amino acids which make hydrogen bonds with Gleevec by providing an oxygen atom (12). When isoleucine takes the place of threonine as a result of C944T mutation, it does not provide oxygen atom for binding (12). Moreover, it contains an extra hydrocarbon group in side chain which results in steric hindrance to Gleevec (12). Thus, binding of drug is completely impaired leading to complete drug resistance (18, 33). Complete Gleevec resistance can be managed clinical by combination therapies (34). Gleevec plus arsenic oxide, Gleevec plus Pegylated interferon-á and Gleevec plus Cytarabine have promising results for CML patients who show complete resistance to Gleevec (20, 35, 36). Moreover some new drugs like Farnesyl transferase inhibitors, Raf kinase inhibitors etc. which stop cancer pathway signaling by bcr-abl oncoprotein have been are under clinical trials with promising initial results (37). Another drug called Genasense which degrades BCR-ABL mRNA has promising results against Gleevec-resistant CML cases (38). Thus it is inferred in present situation that mutation detection related to Gleevec resistance has a great clinical importance. Gleevec resistance can be detected very early in one to three months after initiation of therapy (21) and molecular typing of Gleevec resistant patients on the basis of nature and location of mutations in ATP-binding domain can help in adjustment of therapy accordingly (18, 21, 35, 39).

It should be kept in mind that impact of mutations on Gleevec resistance reported so far is based on a single mutation for each patient. As this is first report of double mutation conferring Gleevec resistance in same patient and each mutation has different impact on drug resistance, biological significance of two or more ABL ATP-binding domain mutations conferring Gleevec resistance in same patient with a difference in resistance mechanism is still to be determined. It is, however, expected that such multiple mutations could result in much complicated Gleevec resistance patterns which might be found more difficult to manage clinically.

Acknowledgments

We especially acknowledge the encouragement, support and appreciation by Dr. Ahmad M. Khalid, Director NIBGE, Pakistan Atomic Energy Commission, Faisalabad, Pakistan. We are thankful to Dr. Ijaz Hussain Shah & associates, Allied Hospital Faisalabad, Pakistan and Dr. Abid Sohail Taj, Institute for Radiology & Nuclear Medicine (IRNUM), Peshawar, Pakistan for their cooperation in sample collection. Technical assistance from Mr. Naeem, Mr. Farooq and Mr. Ansaar is also appreciated.

References

- Goldman JM, Melo JV. Chronic myeloid leukemia-advances in biology and new approaches to treatment. N Engl J Med. 2003;349(15):1451–1464. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra020777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steensma DP. The chronic myeloproliferative disorders: an historical perspective. Curr Hematol Rep. 2003;2(3):221–230. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kantarjian H, O'Brien S, Cortes J et al. Sudden onset of the blastic phase of chronic myelogenous leukemia: patterns and implications. Cancer. 2003;98(1):81–85. doi: 10.1002/cncr.11477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cortes J, Talpaz M, O'Brien S et al. Effects of age on prognosis with imatinib mesylate therapy for patients with Philadelphia chromosome-positive chronic myelogenous leukemia. Cancer. 2003;98(6):1105–1113. doi: 10.1002/cncr.11629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kantarjian H, O'Brien S, Cortes J et al. Analysis of the impact of imatinib mesylate therapy on the prognosis of patients with Philadelphia chromosome-positive chronic myelogenous leukemia treated with interferon-alpha regimens for early chronic phase. Cancer. 2003;98(7):1430–1437. doi: 10.1002/cncr.11665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sattler M, Scheijen B, Weisberg E, Griffin JD. Mutated tyrosine kinases as therapeutic targets in myeloid leukemias. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2003;532:121–140. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4615-0081-0_11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie Y, Davies SM, Xiang Y, Robison LL, Ross JA. Trends in leukemia incidence and survival in the United States (1973-1998). Cancer 2003; 97(9):2229-2235. Erratum in: Cancer 1993; 98(3):659. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Kuhr T, Burgstaller S, Apfelbeck U et al. A randomized study comparing interferon (IFN alpha) plus low-dose cytarabine and interferon plus hydroxyurea (HU) in early chronic phase chronic myeloid leukemia (CML). Leuk Res. 2003;27(5):405–411. doi: 10.1016/S0145-2126(02)00223-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deininger MW, Druker BJ. Specific targeted therapy of chronic myelogenous leukemia with imatinib. Pharmacol Rev. 2003;55(3):401–423. doi: 10.1124/pr.55.3.4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujii T, Inoue S, Karashima T et al. Real-time PCR quantification of bcr/abl chimera and WT1 genes in chronic myeloid leukemia. Rinsho Byori. 2003;51(9):839–846. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hochhaus A. Cytogenetic and molecular mechanisms of resistance to imatinib. Semin Hematol. 2003;40(2 Suppl 3):69–79. doi: 10.1053/shem.2003.50045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorre ME, Mohammed M, Ellwood K et al. Clinical resistance to STI -571 cancer therapy caused by BCR-ABL gene mutation or amplification. Science. 2001;293(5531):876–880. doi: 10.1126/science.1062538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shah NP, Nicoll JM, Nagar B et al. Multiple BCR-ABL kinase domain mutations confer polyclonal resistance to the tyrosine kinase inhibitor imatinib (STI571) in chronic phase and blast crisis chronic myeloid leukemia. Cancer Cell. 2002;2(2):117–125. doi: 10.1016/S1535-6108(02)00096-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu WH, Makrigiorgos GM. Sensitive and quantitative detection of mutations associated with clinical resistance to STI-571. Leuk Res. 2003;27(11):979–982. doi: 10.1016/S0145-2126(03)00066-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- von Bubnoff N, Peschel C, Duyster J. Resistance of Philadelphia-chromosome positive leukemia towards the kinase inhibitor imatinib (STI571, Glivec): a targeted oncoprotein strikes back. Leukemia. 2003;17(5):829–838. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2402889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Branford S, Rudzki Z, Walsh S et al. Detection of BCR-ABL mutations in patients with CML treated with imatinib is virtually always accompanied by clinical resistance, and mutations in the ATP phosphate-binding loop (P -loop) are associated with a poor prognosis. Blood. 2003;102(1):276–283. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-09-2896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roumiantsev S, Shah NP, Gorre ME et al. Clinical resistance to the kinase inhibitor STI-571 in chronic myeloid leukemia by mutation of Tyr-253 in the Abl kinase domain P-loop. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99(16):10700–10705. doi: 10.1073/pnas.162140299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roche-Lestienne C, Preudhomme C. Mutations in the ABL kinase domain pre-exist the onset of imatinib treatment. Semin Hematol. 2003;40(2 Suppl 3):80–82. doi: 10.1053/shem.2003.50046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Druker BJ. Imatinib alone and in combination for chronic myeloid leukemia. Semin Hematol. 2003;40(1):50–58. doi: 10.1053/shem.2003.50000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- La Rosee P, Johnson K, O'Dwyer ME, Druker BJ. In vitro studies of the combination of imatinib mesylate (Gleevec) and arsenic trioxide (Trisenox) in chronic myelogenous leukemia. Exp Hematol. 2002;30(7):729–737. doi: 10.1016/S0301-472X(02)00836-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roche-Lestienne C, Soenen-Cornu V, Grardel-Duflos N et al. Several types of mutations of the Abl gene can be found in chronic myeloid leukemia patients resistant to STI571, and they can pre-exist to the onset of treatment. Blood. 2002;100(3):1014–1018. doi: 10.1182/blood.V100.3.1014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sambrook J, Fritsch EF, Maniatis T. Molecular Cloning: A Laboratory Manual, 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor, NY: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, 1989: E.3-E.4.

- Sillaber C, Mayerhofer M, Agis H, Sagaster V et al. Chronic myeloid leukemia: pathophysiology, diagnostic parameters, and current treatment concepts. Wien Klin Wochenschr. 2003;115(13-14):485–504. doi: 10.1007/BF03041033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steegmann JL, Moreno G, Alaez C et al. Chronic myeloid leukemia patients resistant to or intolerant of interferon alpha and subsequently treated with imatinib show reduced immunoglobulin levels and hypogammaglobulinemia. Haematologica. 2003;88(7):762–768. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garside R, Round A, Dalzell K et al. The effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of imatinib in chronic myeloid leukaemia: a systematic review. Health Technol Assess. 2002;6(33):1–162. doi: 10.3310/hta6330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Dwyer ME, Mauro MJ, Druker BJ. STI571 as a targeted therapy for CML. Cancer Invest. 2003;21(3):429–438. doi: 10.1081/CNV-120018235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azam M, Latek RR, Daley GQ. Mechanisms of autoinhibition and STI-571/imatinib resistance revealed by mutagenesis of BCR-ABL. Cell. 2003;112(6):831–843. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00190-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gambacorti-Passerini C, Piazza R, D'Incalci M. Bcr-Abl mutations, resistance to imatinib, and imatinib plasma levels. Blood. 2003;102(5):1933–1934. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-05-1629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bugert P, Lese A, Meckies J, Zieger W, Eichler H, Kluter H. Optimized sensitivity of allele-specific PCR for prenatal typing of human platelet alloantigen single nucleotide polymorphisms. Biotechniques. 2003;35(1):170–174. doi: 10.2144/03351md05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerstner A, DeFord JH, Papaconstantinou J. Comparison of two PCR-based methods and automated DNA sequencing for prop-1 genotyping in Ames dwarf mice. Mutat Res. 2003;528(1-2):37–44. doi: 10.1016/s0027-5107(03)00080-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Latorra D, Campbell K, Wolter A, Hurley JM. Enhanced allele-specific PCR discrimination in SNP genotyping using 3' locked nucleic acid (LNA) primers. Hum Mutat. 2003;22(1):79–85. doi: 10.1002/humu.10228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kantarjian HM, Talpaz M, O'Brien S et al. Dose escalation of imatinib mesylate can overcome resistance to standard-dose therapy in patients with chronic myelogenous leukemia. Blood. 2003;101(2):473–475. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-05-1451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCann SR, Gately K, Conneally E et al. Molecular response to imatinib mesylate following relapse after allogenic SCT for CML. Blood. 2003;101(3):1200–1201. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-09-2932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Druker BJ. Imatinib alone and in combination for chronic myeloid leukemia. Semin Hematol. 2003;40(1):50–58. doi: 10.1053/shem.2003.50000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- La Rosee P, Johnson K, Corbin AS, Stoffregen EP, Moseson EM, Willis S, Mauro MM, Melo JV, Deininger MW, Druker BJ. In vitro efficacy of combined treatment depends on the underlying mechanism of resistance in imatinib-resistant Bcr-Abl positive cell lines. Blood. 2004;103(1):208–215. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-04-1074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Brien S, Giles F, Talpaz M et al. Results of triple therapy with interferon-alpha, cytarabine, and homoharringtonine, and the impact of adding imatinib to the treatment sequence in patients with Philadelphia chromosome-positive chronic myelogenous leukemia in early chronic phase. Cancer. 2003;98(5):888–893. doi: 10.1002/cncr.11620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yee KW, Keating A. Advances in targeted therapy for chronic myeloid leukemia. Expert Rev Anticancer Ther. 2003;3(3):295–310. doi: 10.1586/14737140.3.3.295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frankel SR. Oblimersen sodium (G3139 Bcl-2 antisense oligonucleotide) therapy in Waldenstrom's macroglobulinemia: a targeted approach to enhance apoptosis. Semin Oncol. 2003;30(2):300–304. doi: 10.1053/sonc.2003.50041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corbin AS, Rosee PL, Stoffregen EP et al. Several Bcr-Abl kinase domain mutants associated with imatinib mesylate resistance remain sensitive to imatinib. Blood. 2003;101(11):4611–4614. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-12-3659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]