Abstract

Immigration is commonly considered to be selective of more able individuals. Studies comparing the educational attainment of Mexican immigrants in the United States to that of the Mexican resident population support this characterization. Upward educational-attainment biases in both coverage and measurement, however, may be substantial in U.S. data sources. Moreover, differences in educational attainment by place size are very large within Mexico, and U.S. data sources provide no information on immigrants’ places of origin within Mexico. To address these problems, we use multiple sources of nationally-representative Mexican survey data to re-evaluate the educational selectivity of working-age Mexican migrants to the United States over the 1990s and 2000s. We document disproportionately rural and small-urban-area origins of Mexican migrants and a steep positive gradient of educational attainment by place size. We show that together these conditions induced strongly negative educational selection of Mexican migrants throughout the 1990s and 2000s. We interpret this finding as consistent with low returns to the education of unauthorized migrants and few opportunities for authorized migration.

INTRODUCTION

Mexican migration to the U.S. has constituted by far the largest single country-to-country flow of international migrants to a developed country in recent decades. In 2000/2001, the United States accounted for 42% of the total stock of immigrants across OECD countries (Belot and Hatton 2012). Mexico at that time accounted for 30% of the U.S.’s foreign-born population, six times more than the next largest country, which was China at 5% (U.S. Bureau of the Census 2003). Because many Mexican migrants stay short periods in the U.S., they constitute an even larger share of its immigrant flow (Passel and Suro 2005). From Mexican data sources, 1.2 million Mexican-born individuals were estimated to have migrated to the United States in 2000, and more than 1 million in each of the next three years (Fernandez-Huertas Moraga 2011). This was larger than the combined flow of all other countries in this period, as measured by U.S. data sources (Passel and Suro 2005). The total Mexican-born population resident in the U.S. almost tripled in size from 4.5 million in 1990 to 12.3 million in 2010 (Passel, Cohn, and Gonzalez-Barrera 2012).

The education of Mexican immigrants is important for both their contributions to the U.S. labor force (Borjas 1995) and for their contributions as parents of second-generation immigrants, whose outcomes as children and adults have been the subject of considerable concern (e.g., Landale, Oropesa, and Llanes 1998). The Mexican population is substantially less educated than the U.S. population, and this has been claimed to be the major reason for the U.S.’s overall less educated immigrant population compared to other countries that are large receivers of immigrants (Antecol, Cobb-Clark, and Trejo 2003). Buttressing this argument that low educational attainment of Mexican migrants is due to the overall low educational attainment of Mexican residents, and not to negative selection into migration, Feliciano (2005, 2008) compared Mexican immigrants in U.S. Censuses to Mexican residents observed in Mexico’s contemporaneous Censuses and concluded that educational selection has been consistently positive from 1960 through 2000. Similarly, Chiquiar and Hanson (2005) characterized their findings from 1990 and 2000 U.S. and Mexican Censuses as intermediate-to-positive with respect to selectivity on education and earnings.

Studies using nationally-representative Mexican data sources, however, have found Mexican migrants to the U.S. to be instead negatively selected from all Mexican residents (Ibarraran and Lubotsky 2007; Fernandez-Huertas Moraga 2011; Ambrosini and Peri 2012). The importance of this finding should not be understated. The theory of positive selection of migrants from their country of origin has a long history in economics (Sjaasted 1962, Chiswick 1999) and is similarly favored in sociology (Portes and Rumbaut 1996). Empirically, the evidence for positive international migrant selection is very strong. Feliciano (2005) found higher educational attainment among immigrants in the U.S. in 2000 than the average educational attainment in all 31 sending countries for which those data were available. Similarly, Aleksynka and Tritah (2013) found higher proportions with a tertiary education among immigrants in 22 European countries than in the home country for 73 out of 76 sending countries.

In the present study, we conduct a more extensive estimation of the educational selectivity of Mexican migrants to the United States than has previously been attempted from nationally-representative Mexican data sources. Although several studies have used Mexican Migration Project (MMP) data to evaluate trends in Mexico-U.S. migration (see Durand and Massey 2004), those data are only designed to be representative at an immigrant sending-community level. A major insight provided by the studies of Ibarraran and Lubotsky and of Fernandez-Huertas Moraga is that the disproportionately rural origins of Mexican migrants can explain much of the overall negative selectivity. Indeed, by using Mexican census data to break down the place-size origins of Mexican migrants much more finely, Ibarraran and Lubotsky concluded that migrants were positively selected by education within all place sizes, but that the lower overall education of smaller places dominated within-place-size positive selectivity to generate overall negative educational selectivity. We follow Ibarraran and Lubotsky’s and Fernandez-Huertas Moraga’s focus on the place-size origins of Mexican migrants as a fundamental means of understanding educational selectivity of all Mexican migrants to the U.S. Whereas Fernandez-Huertas Moraga considered only rural versus urban migration, however, we divide urban migrant sources into three categories and find that the smaller urban categories both contribute proportionately more migrants and have correspondingly lower educational attainment. Whereas Ibarraran and Lubotsky rely solely on the prediction of educational attainment of migrants from the educational attainment of non-migrants, we use both directly-observed migrant educational attainment and migrant educational attainment that is predicted from a combination of non-migrants’ and migrants’ educational attainments. Finally, whereas Fernandez-Huertas Moraga and Ibarraran and Lubotsky focus on migration occurring in the years immediately before or after the likely peak migration year of 2000 (Passel and Suro 2005), our analysis spans the entire 1990s and 2000s decades.

We address the question of the educational selectivity of working-age migrants with Mexican data from a periodic cross-sectional demographic survey, two large-scale surveys of employment and population, and from a panel survey designed to follow emigrants from Mexican households after they moved to the U.S. Together these surveys cover migration from Mexico to the U.S. over the period from 1987 to 2010. All these surveys are, by their design, nationally representative. Typically for data sources on international migration (Bilsborrow et al 1997), each is more representative of some types of migration flows and less representative of other types. Together, however, they allow us to re-evaluate Mexican working-age immigrant educational selectivity more thoroughly and robustly than has been possible in previous studies using either U.S. or Mexican data sources. To anticipate our results, we find remarkable stability in the place-size composition of Mexico’s migrants to the U.S., strongly favoring rural and small-urban places throughout the 1990s and 2000s. We document a steep positive educational gradient of the resident population by place size. The combined force of these two phenomena produces a strong negative educational selectivity of migrants with respect to the overall Mexican population from which migrants are drawn. Particularly striking is our finding of a consistently much lower proportion of migrants than residents with any upper secondary school education. An implication of this is that more than half of the very low proportion of Mexican migrants with the U.S. equivalent of a high school graduate education derives from the consistently low relative probability that a Mexican resident with at least that level of education would migrate to the U.S.

Literature Review

Immigration has commonly been considered to be selective of healthier and more able individuals who are motivated by greater opportunities in the destination country (e.g., Portes and Rumbaut 1996). The hypothesis of positive immigrant self-selection also follows from the theory of immigration as an investment most likely to be undertaken by individuals whose labor-market characteristics produce the highest return on that investment (Chiswick 1999). Immigrants are hypothesized to be less positively self-selected when, due to geographical proximity, the cost of investing in migration is lower (Sjaasted 1962, Grogger and Hanson 2011).

As we noted above, the conclusions about the direction of migrant selectivity in empirical studies of Mexico-U.S. immigration depend strongly on whether U.S. or Mexican data are used to estimate the education of migrants. To explain this discrepancy, both Fernandez-Huertas Moraga (2011) and Ibarraran and Lubotsky (2007) attributed the positive educational selectivity findings of studies using U.S. data to a combination of coverage and measurement biases in those data sources. On coverage biases, Lindstrom and Massey (1994) concluded that the lower education among Mexican Migration Project data (MMP) migrants surveyed in the U.S. than among Mexican immigrants surveyed in the 1990 U.S. Census was likely due to under-coverage of less educated migrants in the Census. Fernandez-Huertas Moraga found that coverage of Mexican migration in the U.S. American Community Survey (ACS) and Current Population Survey (CPS) was approximately half the level estimated from the ENE. Given these discrepancies, Passel et al (2012) switched from using U.S. sources to using Mexican data sources for their primary estimates of Mexican migration. Ibarraran and Lubotsky (2007) also noted that differences in Mexican and U.S. school systems may lead to over-reporting of high school graduate levels of educational attainment among Mexican-born individuals in U.S. data sources. Moreover, they noted that the Census Bureau imputes the education for as many as a fifth of Mexican-born individuals in the U.S., but using predictor variables not including nativity. This is similarly likely to inflate the education levels of Mexican immigrants. Chiquiar and Hanson (2005) acknowledged an additional bias due to schooling years obtained in the U.S. potentially inflating the educational attainment of Mexican migrants.

The studies so far of educational selectivity based on Mexican data sources, however, are also not without their limitations. Education is not reported for migrants who are no longer in the Mexican Census household, leading Ibarraran and Lubotsky (2007) to impute all migrants’ education based on non-migrants of similar ages, genders, household characteristics, and locations. This will miss, for example, dynamics within families in which a sibling who does less well at school is more likely to choose migration to the U.S., as suggested by the ethnographic findings of Kandel and Massey (2002). Fernandez-Huertas Moraga’s (2011) analyses of the ENE are limited to quarterly emigration, cover only the 2000-2004 period, and divide Mexico’s communities only dichotomously into rural (population < 2,500) versus urban place size. Finally, both studies relied on the presence of a non-migrating family member in the household to report moves to the U.S. by other family members. Studies using the Mexican Family Life Survey (e.g., Ambrosini and Peri 2012) suffer from having too few migrants for detailed analyses by place size to be feasible, and a long (three-year) migration interval that may confound propensities to emigrate with propensities to return.

Several recent studies have analyzed urban-origin migrants (e.g., Fussell 2004; Hamilton and Villarreal 2012), noting their apparently increasing share among all migrants. This trend has been described from several data sources that are not designed to be nationally representative with respect to Mexican migrants or households (e.g., Marcelli and Cornelius 2001; Garip 2012). We have not, however, found studies that have shown clear trends towards more urban origins when estimated from nationally-representative data sources. Durand, Massey, and Zenteno (2001), using the nationally-representative 1992 National Survey of Demographic Dynamics (ENADID) to analyze labor migrants, found similar distributions of migrants by place-size in the early 1990s as in the early 1970s, with almost two thirds of migrants originating from places with fewer than 15,000 people, although they also found evidence of increases in migration from places with populations above 100,000 through the late 1980s.

An increasing proportion of female migrants from Mexico has also been described by previous authors (Kana’iaupuni 2000; Cerrutti and Massey 2001), but again not in reference to estimates from nationally-representative data sources. An increasing female proportion could improve the overall educational selectivity of migrants due to female migrants being more positively selected on education than are male migrants (Kana’iaupuni 2000; Feliciano 2008). Durand et al’s (2001) analyses of ENADID labor migrants, however, found that no increase in the female proportion of migrants occurred between the early 1970s and the early 1990s. If female migration is predominantly driven by family unification reasons (Cerrutti and Massey 2001), though, it is not clear that such an evolution would be captured in an exclusively labor-migrant data series.

As a major part of evaluating whether and what changes in educational selectivity occurred over the period, we estimate from nationally-representative Mexican data sources whether and how both the place-size and gender distributions changed over the 1990s and 2000s. Contrary to the above-cited studies, we find remarkable stability in the proportions of migrants from rural and urban Mexico with, if anything, an increased tendency for migrants to come from rural and small-urban places, and we find remarkable stability also in the dominance of male migrants in the flows over the 1990s and 2000s. Our demonstration of the stability of migrant place-size and gender distributions is a major component of our argument that the overall educational selectivity of migrants has been consistently negative over these two decades.

DATA AND METHODS

Our objective is to estimate the difference between the educational distribution of Mexican migrants to the U.S. and that of all Mexican residents of the same ages or birth cohorts. This objective defines our study’s concept of migrant educational selectivity as a primarily demographic one. We define our age range of interest as 18 to 54, or “working ages”. The lower age limit is chosen partly to avoid the confounding of educational attainment accumulated in the U.S. after migration, consistent with our definition of the highest educational attainment category given below. An upper age limit above 54 might confound different migrant selection processes in working and retirement ages.

Our analyses use educational attainment classifications that are based on the Mexican educational system and that are measured consistently across Mexican survey data sources. The highest of our five educational attainment categories consists of those who began upper secondary school (‘preparatoria’), and who may or may not have completed it (equivalent to graduating from high school in the U.S.), and who may or may not have also gone on to college. We do not further sub-classify this group for two reasons. First, it allows us to start at as young as age 18 in defining the highest level of educational attainment. Educational attainment, as we categorize it, is therefore no longer still increasing within our “working-age” population. Second, the proportions of migrants with educational attainment in this highest category are relatively small, ranging in our estimates from 1 in 10 at the beginning of the 1990s to 1 in 4 at the end of the 2000s. The analytical benefits to further subdividing this group are therefore not especially great. We distinguish four categories of education below this highest level: did not complete elementary school (‘primaria’); completed elementary school (and no more); started but did not complete lower secondary school (‘secundaria’); and completed lower secondary school. Since 1993, it has been legally mandated that all children in Mexico complete lower secondary school (Secretaria de Educacion Publica 1993), but we know of no evidence indicating that this law has been enforced.

We analyze Mexico-to-U.S. migrants’ educational selectivity using four nationally-representative Mexican data sources covering the 1990s and 2000s. Details of the data sources are provided in [SELF-IDENTIFYING REFERENCE; Appendix 1]. Our unifying data source over this period is the National Survey of Population Dynamics (ENADID, INEGI 2003), conducted in 1992, 1997, 2006, and 2009. We add to this ENADID series the 2002 National Employment Survey (ENE), whose Migration Module is based on that of the ENADID (INEGI 2004). Two analytical purposes are served by the ENADID/ENE 1992-2009 series. First, it allows us to estimate the educational distribution of all Mexican residents in our target 18 to 54 age range, and additionally by four categories of place size (‘rural’ and three ‘urban’ size categories). It does so across five time points over the two decades over which we estimate migrants’ educational selectivity. Second, the ENADID/ENE 1992/2009 data allow us to construct two series of migrants’ educational distributions: an observed series for circular labor migrants; and a predicted series for all migrants. By comparison of these series to similar-age residents’ educational-attainment distributions, we are able to estimate two series of migrant educational selectivity across the 1990s through 2000s period.

We estimate directly the distributions of all migrants by place-size and by individual and household socio-demographic characteristics (not including education) from the section of the ENADID/ENE questionnaire that asks the household respondent to report all individuals who migrated internationally from the household in the past five years. We use a one-year migration interval (the year immediately preceding the survey) for this “all-migrants” series, facilitating comparability with other sources of annual migration estimates. The reporting of migrants only in the last year also reduces bias due to omission of those who departed less recently. The identification of the place-size origins of all migrants to the U.S. consistently across five time points spanning the 1990s and 2000s ---- 1991-92, 1996-97, 2001-02, 2005-06, and 2008-09 ---- is an especially valuable contribution of this series. The place-size origins of Mexican migrants to the U.S. are not available in U.S. data sources, but constitute a core element of our analysis of Mexican migrants’ educational selectivity. The ENADID/ENE 1992-2009 all-migrant series also produces much larger estimated migration flows than do corresponding U.S. data sources. This constitutes a second major strength of the data for our analysis, especially given concerns that U.S. data sources may disproportionately omit less educated migrants.

This annual all-migrant series by itself is not sufficient for our analysis, however, because at none of the five time points in the series is educational attainment collected for all migrants. Educational attainment is collected for circular, labor migrants at four of the five time points of the ENADID/ENE series. These migrants are captured in a separate section of the questionnaire. They are identified by the survey respondent as “part of the household,” whether or not they are physically present (or in the country) at the time of the survey, and whose last move to the U.S. occurred within the five years before survey date. In the years 1992, 1997, and 2002, the survey’s identification of circular migrants was restricted to those who migrated “for work or to look for work,” whereas in 2009 it included all those who “left to live in the U.S.” (but who similarly were currently living in, or were still part of, the household). We omit the 2006 ENADID from this circular-migrant series because educational attainment was not collected. We use the four other ENADID/EDE surveys to estimate educational selectivity of circular migrants whose last migration to the U.S. occurred respectively in 1987-1992, 1992-1997, 1997-2002, and 2005-2009. The use of a five-year interval is consistent with the nature of circular migration and increases both sample sizes and the comprehensiveness of the periods of migration reported. The main roles of the circular migrant series in our analysis are to estimate educational selectivity from a direct source that covers a major component of all migrants across both the 1990s and 2000s, and to explore any changes in the educational selectivity of these migrants over the two decades.

Estimating educational selectivity for circular migrants only, however, is insufficient for our goal of characterizing the educational selectivity of all migrants over the 1990s and 2000s. We turn to two additional Mexican survey data sources to complete this task. They are the 2002 and 2005 waves of the Mexican Family Life Survey (MxFLS, Rubalcava and Teruel 2007), and the 20 quarters across five calendar years, 2006 to 2010, of the National Survey of Occupation and Employment (ENOE, INEGI 2005). We first estimate the educational selectivity of all migrants in the 2000s directly from the 2002-2005 MxFLS and the 2006-2010 ENOE. We additionally estimate the educational selectivity of the ENADID/ENE annual all-migrants series across the 1990s and 2000s using the 2006-2010 ENOE as an auxiliary data source to predict ENADID/ENE migrants’ educational attainment. We alternately use the 2002-2005 MxFLS as the auxiliary data source in a robustness check.

The ENOE is a quarterly survey similar to the U.S. Current Population Survey. Residences are surveyed in five consecutive quarters. The quarterly panel design permits observation of migrants’ education immediately before emigration, and captures migration events that occurred from one quarter to the next. Migrants are identified from households in which at least one member is still in the household in the next quarter to report the migrant’s having departed. This proxy reporting of migration events is similar to the ENADID’s migration reporting, but the ENOE’s shorter duration between the migration event and its reporting is expected to reduce the frequency of omission due to nobody remaining to report the move. The fieldwork operations of the MxFLS, uniquely among nationally-representative Mexican surveys, follow migrants into the U.S. The MxFLS thereby has the major advantage of identifying migrants even when nobody remains in Mexico to report the migration (e.g., when the whole household migrates to the U.S. at the same time). This allows for evaluation of the sensitivity of our estimates from the ENADID and ENOE to bias due to cases where no household member remains to report a move. The MxFLS, however, has the smallest migrant sample sizes of all our data sources, and its three-year period for migration confounds emigration and return migration by omitting emigration events in cases where the migrant has returned by 2005.

The use of the ENOE, and alternately the MxFLS, as an auxiliary data source in the generation of predicted migrant educational distributions for the annual all-migrant ENADID/ENE series extends the method used by Ibarraran and Lubotsky (2007) to predict educational distributions of migrants reported in the 2000 Mexican Census. Those authors used the observed educational attainment of otherwise similar residents to predict the educational attainment distributions of migrants, whose educational attainment was unobserved. Our extensions of their method are first with respect to the period covered by our estimates ---- as far back as 1991/92 and as far forward as 2008/09. Second, we incorporate a “migrant premium” estimated from auxiliary data in which educational attainment is observed for both migrants and non-migrants. This premium, which may be positive or negative, allows the educational attainment of migrants to differ from that of non-migrants with otherwise identical observed socio-demographic characteristics. Our preferred auxiliary data source is the 2006-2010 ENOE, due to its much larger migrant sample size (4,925, versus 554 in the 2002-2005 MxFLS), and because the sampling designs and the definitions of migrants in the ENOE are closer to those of the ENADID/ENE series. When we conducted alternative estimates using the MxFLS as our auxiliary data source, however, the results changed little. Because, as we show in the Results section below, the magnitudes of the estimated educational selectivity of migrants are somewhat less negative in the ENOE than in the MxFLS, our predicted educational attainment results are conservative with respect to our study’s main conclusion that Mexican migrants to the U.S. are strongly negatively selected on education. Details of this prediction method, and of the alternate, MxFLS results, are provided in the Appendix.

Because our goal throughout is to compare the educational distributions of migrants to the educational distributions of their same-age peers resident in Mexico, we age-standardize (reweight) the educational distributions of the residents in each of our data sources before comparing them to both our observed and predicted migrants’ educational distributions (e.g., Smith 1992). We standardize the residents’ educational distributions using the migrants’ age distribution across three age groups ---- 18-24, 25-34, and 35-54. We use only three age groups due to the small sample sizes of migrants especially in the MxFLS. Migrants everywhere are typically concentrated among younger adults (Plane 1993), and this is true also for Mexico-U.S. migrant streams. As we show below, in each of the five years we analyze across the 1990s and 2000s, 18 to 24 year old migrants account for as many as a third to two fifths of all 18 to 54 year old migrants, and 25 to 34 year old and 35 to 54 year old migrants each account for between a quarter and a third of migrants. The effect of age-standardizing the resident population to our respective migrants’ age distribution is to generate a more educated comparison group. This is due to the combination of relative youthfulness of migrants and educational progress over time that generates higher educational attainment among younger individuals.

RESULTS

We present our results in three parts. First, we use the series of five ENADID/ENE surveys to compare over the 1992 to 2009 period the socio-demographic characteristics, including place-size but not educational attainment, of all migrants and of all Mexican residents. We also describe the differences in educational attainment of all residents by place-size over the period. Second, we present direct estimates of migrant educational selectivity, of circular migrants in the ENADID/ENE surveys between 1992 and 2009, and of all migrants as captured in two household surveys in the 2000s. Third, we present estimates of educational selectivity of migrants in the ENADID/ENE all-migrant series, for whom we predict rather than observe educational attainment.

Place-Size Composition of Migrants and the Educational Attainment of Residents by Place-size

The two decades of the 1990s and 2000s were marked by large changes in the sizes of annual migration flows from Mexico to the U.S. but remarkably constant distributions of migrants by place size. Distributions of 18 to 54 year old Mexican residents and migrants by place size and other socio-demographic characteristics from 1992 to 2009 are shown in Table 1. We define here a ‘migrant’ as any person from the household who migrated to the U.S. in the 12 months before the survey. Total annual migration of 18 to 54 year olds rose from 497,577 in the 1991/92 year to 636,642 in 1996/97 and 726,493 in 2001/02 before declining to 418,853 in 2005/06 and only 243,707 in 2008/09. These are consistently between 1.5 and 2 times higher than all-ages estimates from U.S. data sources (Passel and Suro 2005), but match the time trends from those same U.S. sources. Passel and colleagues (Passel et al 2012) subsequently updated their estimates of Mexican migration using Mexican data sources, and estimated similar levels of annual migration to those we report here.

Table 1.

Socio-demographic characteristics of annual Mexico-U.S. migrants and Mexican residents age 18 to 54, 1991-2009

| 1991-92 migrants^ |

1992 residents^ |

1996-97 migrants^ |

1997 residents~ |

2001-02 migrants~ |

2002 residents~ |

2005-06 migrants^ |

2006 residents^ |

2008-09 migrants^ |

2009 residents^ |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Place size | ||||||||||

| < 2,500 ("Rural") | 47.4 | 25.2 | 45.7 | 22.4 | 45.3 | 20.9 | 43.0 | 20.5 | 46.7 | 19.4 |

| 2,500 to 19,999 | 17.7 | 13.7 | 19.8 | 15.3 | 18.9 | 12.7 | 20.8 | 13.1 | 21.1 | 13.1 |

| 20,000 to 99,999 | 8.6 | 8.2 | 12.5 | 11.2 | 16.8 | 13.3 | 13.3 | 14.2 | 11.3 | 14.6 |

| 100,000+ | 26.3 | 52.9 | 22.0 | 51.1 | 19.1 | 53.1 | 22.8 | 52.2 | 21.0 | 52.9 |

| Percentage male | 83.2 | 48.4 | 82.5 | 47.9 | 87.0 | 47.0 | 82.6 | 47.9 | 80.6 | 48.1 |

| Percentage unauthorized* | - | - | - | - | 80.8 | - | 84.7 | - | 71.3 | - |

| Age group | ||||||||||

| 18 to 24 | 43.1 | 28.7 | 41.3 | 28.7 | 37.7 | 25.6 | 34.2 | 24.5 | 39.2 | 24.5 |

| 25 to 34 | 30.7 | 35.1 | 33.1 | 31.7 | 30.7 | 30.3 | 34.2 | 30.2 | 28.1 | 28.6 |

| 35 to 54 | 26.2 | 36.2 | 25.7 | 39.6 | 31.6 | 44.2 | 31.6 | 45.3 | 32.7 | 46.9 |

| Relationship to head | ||||||||||

| Head or spouse/partner | 42.0 | 63.8 | 41.8 | 63.2 | 47.0 | 62.4 | 49.2 | 62.7 | 27.4 | 58.6 |

| Child | 47.1 | 27.9 | 43.4 | 28.4 | 43.0 | 29.1 | 37.9 | 28.7 | 46.1 | 29.4 |

| Other | 10.9 | 8.3 | 14.8 | 8.4 | 10.0 | 8.5 | 12.9 | 8.6 | 26.5 | 12.0 |

| Population number of migrants |

497,577 | 636,642 | 726,493 | 418,853 | 243,707 | |||||

| Sample size | 1,936 | 122,963 | 2,579 | 155,144 | 1,566 | 300,576 | 658 | 70,306 | 807 | 175,655 |

Notes:

Authors' calculations from the 1992, 1997, 2006, and 2009 National Survey of Demographic Dynamics (ENADID)

Authors' calculations from the 2002 National Employment Survey (ENE)

Not authorized to work in the U.S.

In each of the five observed years from 1992 to 2009, consistently around two thirds of all migrants departed from rural (population < 2,500) or small-urban (population 2,500 to 20,000) areas, whereas only one third of Mexicans in the 2000s, and fewer than two fifths in the 1990s, resided in rural or small-urban areas. Between 43 and 47% of all migrants departed from rural Mexico in each of the five years we describe. These latter fractions are comparable to the estimates of Ibarraran and Lubotsky (2007), who found from analyses of the 2000 Mexican Census that 42.5% of all male migrants age 16 to 54 departed from a rural household, and to the estimates of Fernandez-Huertas Moraga (2011) from the 2000 to 2004 National Employment Survey, who found that 43% of migrants of both sexes age 16 to 65 (45% of male and 34% of female migrants) departed from a rural household. The degree of urbanization in Mexico, meanwhile, has been relatively high throughout the 1990s and 2000s (Anzaldo and Barron 2009). We find that only a quarter (25.2%) of 18 to 54 year olds in 1992 lived in rural areas, falling to one fifth (19.4%) by 2009. The proportion of all 18 to 54 year old migrants from large urban areas (population > 100,000) declined from 26.3% in 1991/92 to 22.4% in 1996/97 and 19.1% in 2001/02, and remained in this one-fifth range in 2005/06 and 2008/09. The proportion of 18 to 54 year olds living in Mexico’s larger urban areas, meanwhile, was consistently just over 50% throughout the 1990s and 2000s. The disproportionately large share of Mexican migrants originating from rural and small-urban areas therefore appears to have increased slightly over the 1990s and 2000s.

Other noteworthy features of the composition of Mexico-U.S. migrant flows are the predominance of men and of undocumented migrants. Upwards of 80% of migrants were male throughout the 1990s and 2000s, with 2001/02 the peak at 87%. Regarding undocumented migrants, in the years 2002, 2006, and 2009, documentation status was asked of all emigrants. The percentage undocumented increased from 80.5% to 84.7% between 2001/02 and 2005/06 before falling to 71.3% in 2008/09. Both these levels and trends are consistent with those reported elsewhere (Hanson 2006; CONAPO 2012). Younger Mexicans predominate among migrants throughout the 1990s and 2000s. Migrants ages 18 to 24 are consistently between 10 and 15 percentage points above their shares of the resident population, and migrants ages 34 to 54 consistently between 10 and 15 percentage points below their shares of the resident population. Finally, although we have no specific hypotheses about the educational selectivity of migrating household heads and spouses versus children of heads and other household members independently of age, we note that there were fluctuations over time in whether heads and spouses or children of heads were more likely to have migrated in the five observed 1990s and 2000s time points.

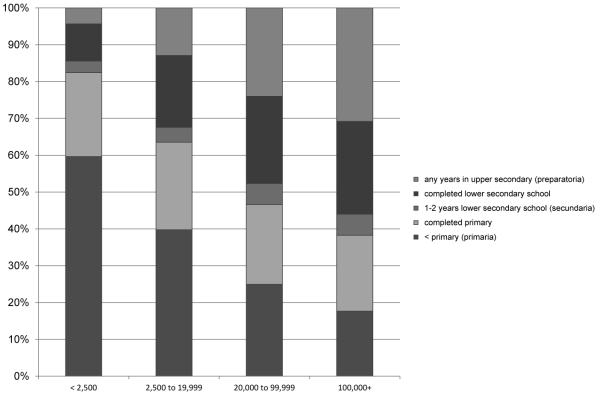

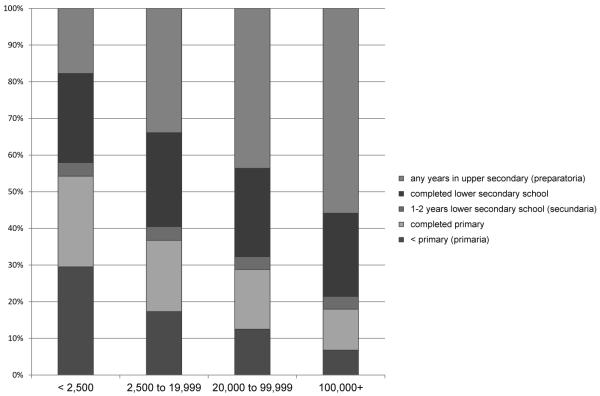

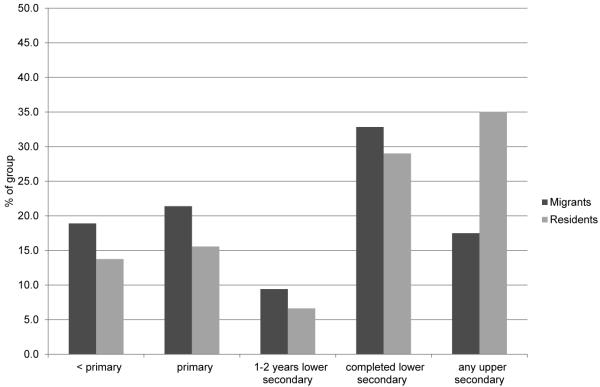

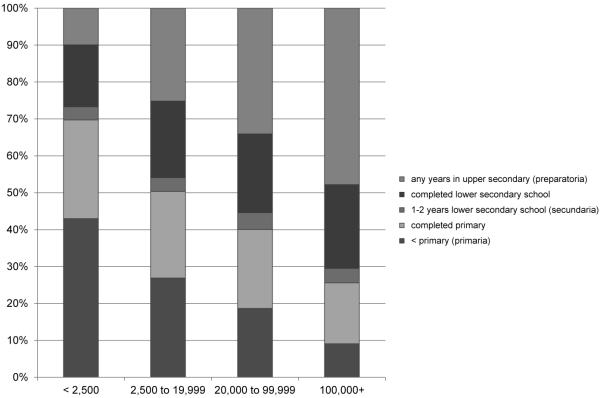

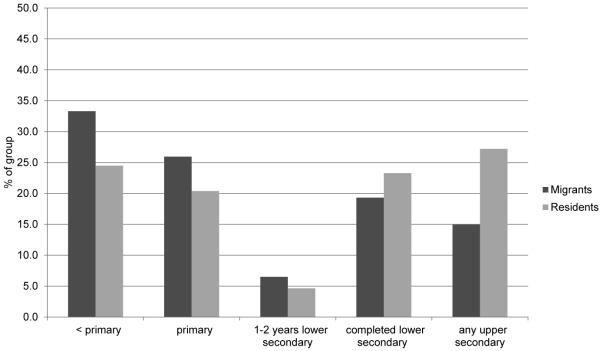

The importance of the disproportionately large shares of migrants from rural and small-urban Mexico for understanding migrant educational selectivity will depend on how steep are the gradients of the educational attainment of the resident population by place size. We present these for the years 1992, 2002, and 2009 (see Figures 1(a) through 1(c)). Considerable educational progress occurred over the 1992 to 2009 period, but from a very low base especially in rural and small-urban areas. In 1992, more than four fifths (82.4%) of rural Mexicans aged 18 to 54 had not progressed beyond elementary school, whereas this was true for under two fifths (38.3%) of urban Mexicans aged 18 to 54. A steep gradient is seen also across our three urban place sizes. In particular, those who had not progressed beyond elementary school accounted for 63.6% of residents aged 18 to 54 in small urban areas. Even in 2009, the majority (54.2%) of rural 18 to 54 year olds, and 36.7% of 18 to 54 year olds in small urban areas, had not progressed beyond elementary school, whereas this was true for under a fifth (18.0%) of 18 to 54 year olds living in large urban areas.

Figure (1a).

Educational Distribution of Mexican Residents Age 18-54 by Place Size, 1992

Source: National Survey of Demographic Dynamics (ENADID)

Figure 1(c).

Educational Distribution of Mexican Residents Age 18-54 by Place Size, 2009

Source: National Survey of Demographic Dynamics (ENADID)

Direct Estimates of Migrants’ Educational Selectivity

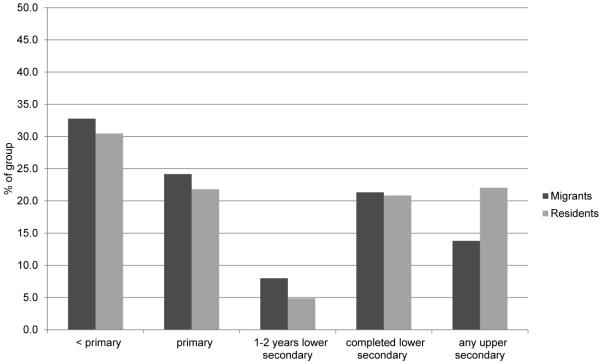

We present first in Figures 2(a) to 2(d) results for educational selectivity of circular migrants in four five-year periods, 1987-1992, 1992-1997, 1997-2002, and 2005-2009. In results not shown, circular migrants were more likely to be household head or spouse and were more evenly distributed across the three age groups than were all migrants, but were similar in their gender composition (more than 80% male) and in their place-size distribution (see SELF-IDENTIFYING REFERENCE, Appendix Table A1.2). Even though circular migrants are only a subset of all migrants, they allow for a first look at the selectivity of Mexican migrants to the U.S. by educational attainment.

Figure 2(a).

Educational Selectivity of Circular migrants in the 1992

National Survey of Demographic Dynamics (ENADID), 1987-92

Source: Authors' calculations. Circular migrants are members of the household who migrated to the U.S. for work any time in the 5 years before the survey. Residents' education distributions are standardized to the migrant age distribution

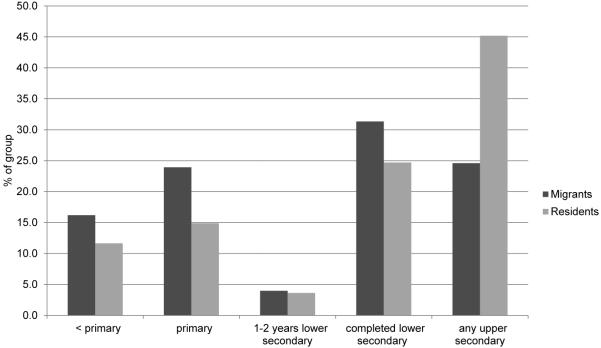

Figure 2(d).

Educational Selectivity of Circular migrants in the 2009

National Survey of Demographic Dynamics (ENADID), 2004-09

Source: Authors' calculations. Circular migrants are members of the household who migrated to the U.S. for work any time in the 5 years before the survey. Residents' education distributions are standardized to the migrant age distribution

We compare the educational distribution of circular migrants to the education distribution of the resident population standardized to the circular migrants’ age distributions. Given the disproportionately large share of circular migrants from rural and small-urban Mexico throughout the 1990s and 2000s, where the population’s educational attainment is much lower, it is unsurprising that we find that circular migrants’ educational attainment relative to all Mexican residents of labor-force age has been consistently lower. In particular, the percentages of circular migrants with no more than an elementary school education were in 1997, 2002, and 2009 around 14 percentage points higher than the percentages of the age-standardized resident population with no more than an elementary school education. The percentages of circular migrants who had continued their schooling past lower secondary school were 8 and 12 percentage points lower than for all 18 to 54 year old residents in the 1992 and 1997 years, and as much as 18 and 21 percentage points lower than for all 18 to 54 year old residents in the 2002 and 2009 years. Thus although the educational attainment of circular migrants improved over time, it did not keep pace with improvements in the educational distribution of all Mexican residents. Circular migrants became increasing more negatively selected on educational attainment across the four time points from 1992 to 2009. These results are consistent with the findings of Campos-Vasquez and Lara (2012) for returning migrants in the 1990 to 2010 Mexican Censuses.

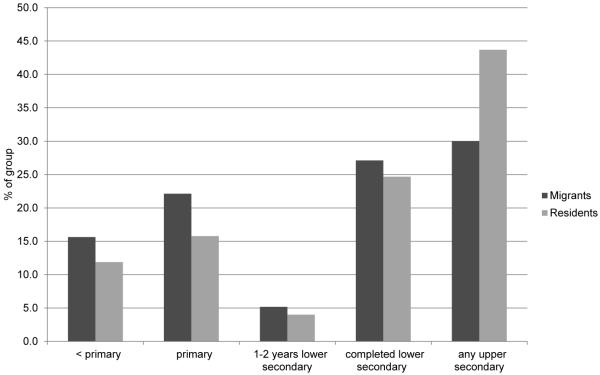

For the 2000s decade, we additionally compare the educational attainment of all migrants to the educational attainment of their same-age resident peers, first for a three-year migration interval from 2002 and 2005 and second for a quarterly migration interval over the years 2006 to 2010. Results are presented respectively in Figures 3 and 4. Reassuringly, the differences between migrants’ and residents’ proportions across our five educational categories for the 2002-2005 interval mirror those for circular migrants from the closest comparison period, 1997-2002 (see again Figure 2(c)). The 17.5% of 2002-2005 migrants in the highest education category of “progressed to upper secondary school” is only half their same-age resident peers’ percentage of 35.0%. At the lower end of educational attainment, 40.3% of migrants had no more than an elementary school education, whereas this was true for only 29.4% of their resident peers. Finally, compared to the 42.2% of migrants with some or complete lower secondary schooling, 35.6% of their resident peers had this level of educational attainment. Thus migrants were disproportionately drawn from the lower and middle education groups in the Mexican educational attainment distribution. Compared to the U.S. educational attainment distribution, of course, the contrast is far greater: 82.5% of Mexican emigrants to the U.S. completed no more than the nominal equivalent of ninth grade (lower secondary school), whereas approaching 90% of U.S.-resident 25 to 34 year olds in 2005 had at least an upper secondary (high school graduate) education (OECD 2007).

Figure 3.

Educational Selectivity of Mexican Family Life Survey (MxFLS ) 2002 to 2005 Migrants

Source: Authors' calculations. Migrants were living in Mexico in 2002 and in the U.S. in 2005. Residents' education distributions are in 2002 and are standardized to the migrant age distribution

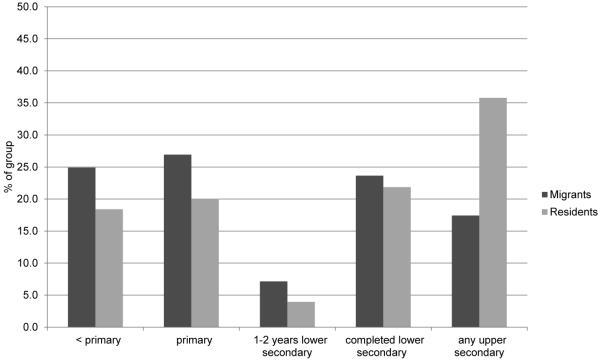

Figure 4.

Educational Selectivity of Quarterly migrants in the National Survey of Occupation and Employment (ENOE 2006-2010)

Source: Authors' calculations. Migrants moved from a household between survey quarters. Residents' education distributions are standardized to the migrant age distribution

Figure (2c).

Educational Selectivity of Circular Migrants in the 2002 National Survey of Employment (ENE) Migration Module, 1997-2002

Source: Authors' calculations. Circular migrants are members of the household who migrated to the U.S. for work any time in the 5 years before the survey. Residents' education distributions are standardized to the migrant age distribution

Quarterly migrants from the 2006 to 2010 period are seen to be again strongly negatively selected on educational attainment, though somewhat less so than three-year migrants in 2002-2005. The 30.0% of migrants in the highest education category (“progressed to upper secondary school”) is still 13.7 percentage points lower than their same-age resident peers’ 43.7%. At the lower end of the educational attainment distribution, 40.3% of migrants had no more than an elementary school education, whereas this was true for only 29.4% of their resident peers. Finally, compared to the 37.7% of migrants who had some or completed lower secondary schooling, this was true for only 27.7% of their same-age resident peers. Thus migrants were again found to be disproportionately drawn from the lower and middle educational attainment levels.

The data sources on three-year and quarterly migrants for the 2000s period also allow us to estimate directly the educational selectivity of all migrants controlling for place size and other socio-demographic variables. In Table 2, we present coefficient estimates for a (male) migrant main effect and a migrant*female interaction effect, both for the 2002 to 2005 three-year migrants and for the 2006 to 2010 quarterly migrants. These equations additionally control for age, gender, relationship to head, and place-size category (see SELF-IDENTIFYING REFERENCE, Appendix Table A2.1 for the full equations). Again our aim is to describe how the educational-attainment distributions of migrants compare to the educational-attainment distributions of non-migrants, and not to estimate how much an increase or decrease in educational attainment changes an individual’s propensity to migrate. Therefore, just as in our graphical comparisons of migrant distributions to age-standardized resident distributions above, the outcome modeled in this regression is the educational-attainment distribution.

Table 2.

Migration Selectivity Parameters Estimated from Multinomial Logit Models of Educational Attainment^

| < Primary | Completed Primary |

Some lower secondary |

Completed lower secondary |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A. Three-year migrants 2002-2005~ | ||||

| Migrant (reference=non-migrant) | 1.102 *** | 1.120 *** | 1.089 *** | 0.899 *** |

| Standard Error | 0.214 | 0.205 | 0.240 | 0.185 |

| Migrant*female | −1.393 *** | −0.890 ** | −0.701 + | −0.559 * |

| Standard Error | 0.345 | 0.315 | 0.407 | 0.280 |

| Migrants | 554 | |||

| Sample size (all migrants + non-migrants) | 17,972 | |||

| B. Quarterly migrants 2006-2010+ | ||||

| Migrant (reference=non-migrant) | 0.991 *** | 1.204 *** | 1.132 *** | 0.884 *** |

| Standard Error | 0.058 | 0.053 | 0.078 | 0.048 |

| Migrant*female | −1.340 *** | −1.116 *** | −0.898 *** | −0.957 *** |

| Standard Error | 0.125 | 0.100 | 0.170 | 0.085 |

| Migrants | 4,925 | |||

| Sample size (all migrants + non-migrants) | 737,056 |

Notes:

Reference educational attainment outcome = any upper secondary school (may have completed upper secondary, may have attended college)

Estimated from the 2002-2005 Mexican Family Life Survey (MxFLS)

Estimated from the 2006-2010 National Survey of Employment and Occupation (ENOE)

Both the MxFLS and ENOE equations control for age, sex, relationship to household head, and place-size (see Appendix Table A2.1 for full regression results, and Appendix Table A1.4 for descriptive statistics on all variables)

p< .001,

p< .01,

p< .05,

+ p< .10

The migrant main-effect coefficients describe the likelihood of being in each of the lower four education categories relative to being in the highest educational category (“progressed to upper secondary school”) among male migrants. Given the different ways that migrants are defined and identified between the two surveys and the different periods, of close to peak migration between 2002 and 2005 versus rapidly declining migration between 2006 and 2010, the similarity of the sets of migrant and migrant*female parameters between the two surveys is striking. Compared to the reference outcome category of at least some upper secondary education, male migrants are much more likely to have any other educational attainment level, controlling for their age, relationship to head, and their place size. That is, male migrants are strongly negatively selected even controlling for our four place-size groups. This is not generally true of female migrants, however, as seen in the ‘migrant*female’ coefficients that are of approximately equal magnitudes to the migrant main-effect coefficients, but with an offsetting negative sign. This approximate canceling out of the migrant main effect coefficients implies a more or less neutral educational selectivity within place size among female migrants.

Overall Educational Selectivity of Annual All-Migrant Streams in the 1990s and 2000s

In the final step of our analysis, we derive predicted values of educational attainment for migrants from the 1991/92 through 2008/09 annual all-migrant series (the series shown in Table 1). Prediction of these all-migrant education distributions is conducted separately by gender, due to educational selection parameters being more negative for male than for female migrants, as described immediately above. We present results in Table 3. To combine the genders, we weight the predicted male and female annual migrants’ educational attainment distributions by the observed ENADID/ENE proportions of male and female migrants (from Table 1). As described in the Data and Method section, the all-migrant educational attainment distributions presented here are generated by combining parameters predicting the observed ENADID/ENE resident educational attainments distributions by place size and socio-demographic variables with migrant-premium parameters estimated from the ENOE residents plus migrants data (see again Table 2). The resident educational attainments against which to evaluate the all-migrants’ educational selectivity are again standardized to the migrants’ age distributions.

Table 3.

Predicted education of annual age 18-54 Mexico-to-U.S. migrants, versus education of age 18-54 Mexican residents

| male migrants+ |

male residents~ |

difference | female migrants^ |

female residents~ |

difference | all migrants+ |

all residents+ |

difference | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1991-92 annual migrants | |||||||||

| Education | |||||||||

| < primary (primaria) | 32.9 | 24.0 | 8.9 | 25.8 | 27.3 | −1.4 | 31.7 | 25.7 | 6.0 |

| completed primary | 32.1 | 22.0 | 10.1 | 32.8 | 25.1 | 7.7 | 32.2 | 23.6 | 8.6 |

| 1-2 years lower secondary school (secundaria) | 7.4 | 6.2 | 1.1 | 5.4 | 4.3 | 1.1 | 7.0 | 5.3 | 1.8 |

| completed lower secondary school | 17.9 | 19.9 | −1.9 | 26.8 | 24.8 | 2.0 | 19.4 | 22.4 | −3.0 |

| any years in upper secondary (preparatoria) | 9.6 | 27.9 | −18.2 | 9.1 | 18.5 | −9.4 | 9.6 | 23.0 | −13.5 |

| 1996-97 annual migrants | |||||||||

| Education | |||||||||

| < primary (primaria) | 29.1 | 23.5 | 5.5 | 16.3 | 27.4 | −11.2 | 26.8 | 25.6 | 1.3 |

| completed primary | 33.1 | 18.9 | 14.2 | 37.3 | 22.1 | 15.2 | 33.8 | 20.5 | 13.3 |

| 1-2 years lower secondary school (secundaria) | 10.0 | 5.3 | 4.6 | 7.0 | 3.8 | 3.1 | 9.5 | 4.6 | 4.9 |

| completed lower secondary school | 21.0 | 21.3 | −0.3 | 31.9 | 23.8 | 8.1 | 22.9 | 22.6 | 0.3 |

| any years in upper secondary (preparatoria) | 6.8 | 30.9 | −24.1 | 7.5 | 22.9 | −15.3 | 6.9 | 26.8 | −19.8 |

| 2001-02 annual migrants | |||||||||

| Education | |||||||||

| < primary (primaria) | 21.8 | 17.9 | 4.0 | 19.1 | 21.3 | −2.2 | 21.5 | 19.7 | 1.8 |

| completed primary | 27.9 | 18.8 | 9.1 | 28.2 | 21.3 | 6.9 | 27.9 | 20.1 | 7.8 |

| 1-2 years lower secondary school (secundaria) | 6.8 | 4.6 | 2.2 | 4.9 | 3.2 | 1.6 | 6.6 | 3.9 | 2.7 |

| completed lower secondary school | 24.8 | 22.0 | 2.7 | 24.7 | 20.2 | 4.6 | 24.7 | 21.1 | 3.7 |

| any years in upper secondary (preparatoria) | 18.7 | 36.7 | −18.0 | 23.1 | 33.9 | −10.9 | 19.2 | 35.3 | −16.0 |

| 2005-06 annual migrants | |||||||||

| Education | |||||||||

| < primary (primaria) | 21.5 | 16.3 | 5.3 | 21.0 | 20.0 | 1.0 | 21.5 | 18.2 | 3.3 |

| completed primary | 25.7 | 16.1 | 9.6 | 24.0 | 17.8 | 6.2 | 25.4 | 17.0 | 8.4 |

| 1-2 years lower secondary school (secundaria) | 7.4 | 4.7 | 2.7 | 5.7 | 3.7 | 2.0 | 7.1 | 4.2 | 2.9 |

| completed lower secondary school | 26.1 | 22.4 | 3.6 | 25.0 | 20.8 | 4.2 | 25.9 | 21.6 | 4.3 |

| any years in upper secondary (preparatoria) | 19.3 | 40.5 | −21.2 | 24.3 | 37.6 | −13.4 | 20.2 | 39.0 | −18.9 |

| 2008-09 annual migrants | |||||||||

| Education | |||||||||

| < primary (primaria) | 17.8 | 12.5 | 5.2 | 14.8 | 14.2 | 0.5 | 17.2 | 13.4 | 3.8 |

| completed primary | 24.6 | 14.8 | 9.8 | 22.6 | 16.4 | 6.2 | 24.2 | 15.6 | 8.6 |

| 1-2 years lower secondary school (secundaria) | 6.3 | 4.1 | 2.2 | 4.6 | 3.0 | 1.6 | 6.0 | 3.6 | 2.4 |

| completed lower secondary school | 28.4 | 24.1 | 4.3 | 27.7 | 23.1 | 4.6 | 28.2 | 23.6 | 4.6 |

| any years in upper secondary (preparatoria) | 23.0 | 44.4 | −21.5 | 30.3 | 43.2 | −12.9 | 24.4 | 43.8 | −19.4 |

Notes:

Authors' calculations from the 1992, 1997, 2006, and 2009 National Survey of Demographic Dynamics (ENADID), 2002 National Survey of Employment (ENE), and National Survey of Occupation and Employment (ENOE) 2006-2010. See text for details.

Standardized to the migrant age distribution

weighted to ENADID/ENE percentages male

We see that migrants’ predicted educational attainment increased greatly between 1991/92 and 2008/09, but that this increase was less than the increase in the educational attainment of their same-age Mexican-resident peers. Because we are holding the migrant premium on educational attainment constant over time (that is, constant by age, sex, relationship to household head, and place size), we interpret the lesser increase in migrants’ than residents’ educational attainment over the two decades as having been driven by the moderate increases in the relative fractions of migrants originating from rural and small-urban Mexico during this period (see again Table 1).

Across all five time periods, 1991/92 through 2008/09, migrants who completed primary school are the most over-represented group relative to the resident population age 18 to 54, and migrants who completed any upper secondary education the most under-represented group. Migrants with any schooling greater than the U.S. equivalent of ninth grade (that is, any Mexican upper secondary education) again are seen to constitute a remarkably low fraction of all migrants, and migrants with no more than a U.S.-equivalent of elementary schooling (Mexican primary education) a remarkably high fraction. In the 1991/92 and 1996/97 years, only 9.6% and 6.9% respectively of all migrants are estimated to have had any years of upper secondary schooling in Mexico, and 19.2%, 20.2%, and 24.4% respectively of all migrants in the 2001/02, 2005/06, and 2008/09 years (see ‘all migrants’ column). Again, these increases in migrant education have failed to keep pace with the overall increase in Mexicans’ going on to this level of education, which rose from 23.0% in 1992 to 43.8% in 2009 (see ‘all residents’ column). Thus migrants’ percentage-point difference from residents’ rose from 13.5 for 1991/92 migrants to 19.4 for 2008/09 migrants. At the other end of the education distribution, our predicted distributions of migrants’ educational attainment exhibit large fractions of migrants with no more than elementary-school education: gradually declining from 63.9% of 1991/92 migrants to 41.4% of 2008/09 emigrants. At the same time, the fractions of similar-age Mexican residents with no more than elementary-school education declined from 49.3% in 1992 to 29.0% in 2009.

In these predicted migrant educational distributions compared to observed resident educational distributions, male migrants are more negatively selected than female migrants. The fraction of male migrants with any years of upper secondary schooling is consistently between 18 and 24 percentage points lower than the fraction with any years of upper secondary schooling among similar-age male Mexican residents. In contrast, the fraction of female migrants with any years of upper secondary schooling is between 9 and 15 percentage points lower than that for similar-age female Mexican residents. However, the modal educational category is ‘completed primary education’ for both male and female migrants through the period 1991/92 through 2005/06, with the minor exception of slightly more 1991/92 male migrants who have less than a primary education. Only in 2008/09 does the modal migrant educational category shift to ‘completed lower secondary school.’ It does so for both male and female migrants. The educational attainment distributions of male and female migrants are therefore not as different from each other as the selectivity results suggest. In the 1990s in particular, this follows from the lower overall educational attainment of the female Mexican resident population relative to the male Mexican resident population.

DISCUSSION

Previous studies of Mexican immigrant educational selectivity have generated mixed conclusions. Findings of intermediate-to-positive selectivity from studies using U.S. data sources (Feliciano 2005, 2008; Chiquiar and Hanson 2005) contrast with findings of negative selectivity from studies using nationally-representative Mexican data sources (Ibarraran and Lubotsky 2007; Fernandez-Huertas Moraga 2011; Ambrosini and Peri 2012; but see also Kaestner and Malamud 2013). In the present study, we focused on the sources of overall educational selectivity in the socio-geographic origins of Mexico’s migrants to the U.S. We used four Mexican survey data sources, each one broadly nationally-representative, though each one different in its definition and coverage of migrants. Analysis of each source, however, resulted in a common finding of strongly negative educational selectivity coincident with a large over-representation of rural and small-urban places of migrant origin. We found no evidence to support the characterization of Mexican migration to the U.S. as becoming increasingly urban in its places of origin, as has been found in analyses of data sources not designed to be nationally representative of Mexico (e.g., Marcelli and Cornelius 2001; Garip 2012). We found instead evidence for increases, albeit relatively small, in the shares of rural and small-urban-area migrants. While there was some redistribution of the Mexican working-age population from rural to, in particular, medium-sized urban areas, there was no corresponding change in the distribution of migrants’ place sizes of origin. Consistently around 45% of all migrants originated from rural Mexico, and this was upwards of twice rural Mexico’s share of all working-age residents. Together, migrants from rural and small-urban areas (population < 20,000) accounted for consistently two thirds of all migrants to the U.S. in the 1990s and 2000s, but only from one third to two fifths of Mexico’s resident working-age population. Throughout the 1990s and 2000s, half of all working-age Mexicans lived in urban areas with populations greater than 100,000, where educational attainment was much higher than in both rural and smaller urban places. These large urban areas, however, were the sources of only one fifth of all working-age migrants to the U.S. in the 2000s, down from a quarter in the early 1990s. We argue that the single most important insight into understanding the educational selectivity of migrants from Mexico to the U.S. is therefore found in the disproportionately large share of migrants that come from rural and smaller urban areas in Mexico.

A second factor counting against the plausibility of overall positive educational selectivity is that men accounted for a large majority of migrants throughout the 1990s and 2000s. Studies have consistently found female migrants to be more positively selected than male migrants (Kana’iaupu 2000; Feliciano 2008). Our own analyses, both in a three-year period from 2002-2005 and quarterly over the 2006-2010 period, indicated relatively strong negative ‘behavioral’ educational selectivity for migrant men (that is, after controlling for place size, age, and relationship to head), and more or less neutral ‘behavioral’ selectivity for migrant women. In aggregate, we found that female migrants’ educational attainments were accordingly somewhat higher than those of male migrants, but less than would have been expected. For the 1990s, though no longer in the 2000s, this was due partly to the lower overall educational levels of women than men in Mexico. One caution is that a downward bias in the estimation of female migrants when the migration is reported by a remaining household member (Hill and Wong 2005) may have contributed to the very low female proportions of migrants estimated from our main data sources. We found that men represented upwards of four fifths of migrants when emigration was reported by household members remaining in Mexico, but only two thirds of migrants when the migrants themselves are followed up after a three-year period. This difference, however, is also consistent with a much higher rate of return migration among men than women (Reyes 2001, 2004). More work remains, therefore, to understand trends in the share of women in migrant flows, and consequences for the overall educational attainment of Mexican migrants to the U.S.

Our findings are important because they indicate that the overall lower levels of educational attainment in Mexico than in the U.S. are only part of the reason for the low overall educational attainment of Mexican migrants to the U.S (Borjas 1995; Antecol et al 2003); negative selection by education in who migrates is also important. In particular, we found a much lower probability that Mexicans with at least some upper secondary school education will migrate to the U.S. compared to the probability for less educated Mexicans. Consequently, the much lower proportion of the high school graduates (translated to U.S.-equivalent years of education) in Mexico than in the U.S. explains no more than half of the low proportion of more educated Mexicans in migrant streams.

Given the preponderance of evidence for overall negative educational selectivity of Mexican emigrants to the U.S. over the 1990s and 2000s found in the present study, what are the most likely causal explanations? Although one prominent alternative economic theory is that higher relative earnings inequality in the sending country than in the receiving country will produce negative selected migrant flows (Borjas 1987), in few cases internationally has this been large enough to dominate differences in absolute returns to education in a higher-income destination country (Liebig and Sousa-Poza 2004; Grogger and Hanson 2011). Grogger and Hanson note, moreover, that the United States has one of the highest returns to education among high-income immigrant-receiving countries and accordingly receives a disproportionately large share of tertiary educated immigrants across OECD countries.

The most persuasive explanation to us is that immigration policy has offered few routes for legal migration to the U.S., together with a large pool of working-age migrants facing low wages in Mexico, much higher wages in the U.S., and relatively low costs of migrating to the U.S. We presented estimates that between 80 and 85% of Mexican migrants to the U.S. were undocumented in the early to mid-2000s, consistent with Passel and Cohn’s (2008) indirect estimates with U.S. data and CONAPO’s (2012) direct estimates with Mexican data. Although this represented a peak, a majority of migrants were undocumented throughout the period of our study (Hanson 2006; CONAPO 2012). The restrictive U.S. immigration policy that has been in place throughout the 1990s and 2000s does not appear to have had the intended effect of deterring unauthorized migration overall (Hanson 2006; Massey and Pren 2012). It may, however, have had a disproportionate deterrent effect on higher-skill migrants relative to lower-skill migrants. This has been shown to be a theoretical possibility by Bellettini and Ceroni (2007) and Bianchi (2013). Empirically, undocumented status has been shown to result in lower wage returns to education (Rivera-Batiz 1999; Hall, Greenman, and Farkas 2010; Massey and Gelatt 2010), with Massey and Gelatt arguing additionally that wage-disadvantaging effects spill over to documented Mexican migrants. Further support for the characterization of U.S. immigration policy as leading to less educated Mexican migrant flows is found in ethnographic evidence from Kandel and Massey (2002). They describe a sorting mechanism within Mexican communities in which Mexican youth view migration to the U.S. as an alternative to staying in school, since additional schooling has little value for the jobs they are likely to obtain in the U.S. Ambrosini and Peri (2012, p.148) similarly conclude that “The option of undocumented migration [is] only attractive for less educated…” They go on to suggest changes to U.S. immigration policy that would target more as well as less educated individuals.

If immigration policy is indeed the primary explanation for the highly unusual phenomenon that we have documented here of negative educational selectivity among Mexican immigrants to the U.S. over these two decades, a final note is that this would not be completely without precedent internationally. According to Bauer et al (2002), who provide evidence specifically on Portugal-Germany flows before Portugal’s entry to the European Union, policies aimed at importing low-skill labor in Germany and several other high-income European countries in the 1970s had the effect of producing overall negative selection of immigrants from neighboring lower-income countries in Southern Europe, Turkey, and Yugoslavia. Higher returns to low-skilled workers in the higher-income European country were claimed to be the key determinant of this phenomenon, again with supporting evidence from Portugal-Germany flows. Although these flows were largely of legal migrants, a common characteristic of immigration policy between the formal programs to import low-skill labor to high-income European countries at that time and the informal migration of low-skill labor to the U.S. from Mexico in recent decades has been the lack of opportunities for high-skill migrants from the source country to realize returns to their higher education and skills in the destination country.

Figure 1(b).

Educational Distribution of Mexican Residents Age 18-54 by Place Size, 2002

Source: National Survey of Employment (ENE)

Figure 2(b).

Educational Selectivity of Circular migrants in the 1997

National Survey of Demographic Dynamics (ENADID), 1992-97

Source: Authors' calculations. Circular migrants are members of the household who migrated to the U.S. for work any time in the 5 years before the survey. Residents' education distributions are standardized to the migrant age distribution

Acknowledgements

We thank Sarah Kups and Ricardo Basurto-Dávila for valuable research assistance, and Emma Aguila, Sung Park, Andrés Villarreal, and participants at presentations of an earlier version of this paper at the 2010 Population Association of America and Mexican Demographic Society meetings and at the UCLA California Population Center seminar series for helpful review and comments. We also gratefully acknowledge support from the National Institute of Aging under investigator grant R21AG030170, and from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development research infrastructure grants R24-HD050906 and R24-HD041041.

Appendix.

Predicting Educational Attainment for the Annual All-Migrant Series

As we noted in the main text, our use of the ENOE, and alternately the MxFLS, as an auxiliary data source in the generation of predicted migrant educational distributions for the annual all-migrant ENADID/ENE series extends the method used by Ibarraran and Lubotsky (2007) to predict educational distributions of migrants reported in the 2000 Mexican Census. Those authors used the observed educational attainment of otherwise similar residents to predict the educational attainment distributions of migrants, whose educational attainment was unobserved. They imputed exactly the same educational distribution to the migrants as to the non-migrants within their finely-drawn demographic “cells”, and then aggregated both up to the national level of “migrant educational selectivity” of their study. Because they had place-size, age, and household composition at the county level for both migrants and migrants, and because educational attainment varies greatly by place size and these other individual, household, and community characteristics, they argued that they were able to estimate with reasonable accuracy the educational attainment of migrants without observing it directly. Their assumption was that within these fine-grained geographic and socio-demographic cells, any differences between the education of migrants and non-migrants would be very small and be dominated by cross-cell variation in educational attainment.

We agree with Ibarraran and Lubotsky that educational distributions of both residents and migrants vary greatly by demographic characteristics including age, gender, household structure, and place size, and therefore that locating where across these socio-demographic cells migrants are most commonly found will tell us much about the educational attainment of all migrants relative to all non-migrants. Accordingly, we use information on the educational attainment of non-migrants within age, gender, relationship to head, and place-size cells in our prediction of the educational attainment of the migrants drawn from those same cells. We relax the assumption, however, that migrants and non-migrants are drawn randomly from all individuals with the same observable socio-demographic characteristics. In order to do this, we bring in an auxiliary data source from which a within-cell “migrant premium” may be estimated.

Our estimation of the migrants’ educational attainment distribution within cells is therefore a combination of non-migrants’ educational attainment distributions within cells and a migrant premium added to that distribution. The prediction is parameterized using a multinomial logit model for the five-category educational attainment. First, parameters of the multinomial logit equation for the five-category educational attainment are estimated for non-migrants (‘residents’) in each of the five years t = 1992, 1997, 2002, 2006, and 2009 years. The ENADID/ENE data on all residents ages 18 to 54 is used for this estimation of parameters βkt, one set for each of the four education outcomes k other than the reference, highest education outcome (any upper secondary). The values of these parameters are presented in [SELF-IDENTIFYING REFERENCE, Appendix Tables A2.1].

Second, a migrant selection equation is estimated. Its specification includes all the same predictors plus a “migrant” predictor and a “migrant*female” predictor, yielding a set of parameters βkt but also two additional coefficients for each of the four education outcomes, γ1k and γ2k. We estimated these alternately from the quarterly migration events of the 2006 to 2010 National Survey of Occupation and Employment (ENOE) and the three-year events of the 2002-2005 Mexican Family Life Survey (MxFLS). Thus we exploit the differences between the longer-duration MxFLS and shorter-duration ENOE definitions of migration in robustness checks on these individual-level, ‘behavioral’ migrant selectivity parameters. The values of these parameters estimated alternately from the ENOE 2006-2010 and the 2002-2005 MxFLS are given in Table 2 of our paper. The full set of coefficients is given in [SELF-IDENTIFYING REFERENCE, Appendix Table A2.2]. We explored the specification and estimation of interactions between ‘migrant’ and other predictors and found no statistically robust patterns across the two sources.

The predicted educational attainment of migrants in each year is then derived from the βkt parameters estimated from the ENADID/ENE residents, plus the migrant-premium parameters γ1k and γ2k estimated from the ENOE 2006-2010. We use the ENOE in preference to the MxFLS due to its much larger migrant sample sizes (4,925 in the ENOE versus 554 in the MxFLS), and because the sampling designs and the definitions of migrants in the ENOE are closer to those in the ENADID/ENE series. We show in [SELF-IDENTIFYING REFERENCE, Table A2.3], compared to Table 3, however, that the results differ little when substituting instead the γ1k and γ2k coefficients estimated from the MxFLS. For each year t, these male and female migrant logits are respectively X’βkt+γ1k and X’βkt+γ1k+γ2k, and the predicted educational probabilities for each of the four lower educational categories are:

| (1) |

and for the reference, highest education outcome, the predicted probabilities for male migrants are given by:

| (1a) |

For female migrants, the corresponding five probabilities are given by:

| (2) |

and

| (2a) |

The final step is simply attaching these predicted probabilities across the distribution of migrants’ regressors X. This distribution comes from the ENADID/ENE annual all-migrant series. The male migrant education distribution is then derived by weighting the probabilities of equations (1) and (1a) by the observed distribution of male migrants by age, relationship to head, and place-size, and the female migrant education distribution is derived by weighting the probabilities of equations (2) and (2a) by the observed distribution of female migrants by age, relationship to head, and place-size. The final step is to weight the predicted male and female emigrants’ educational attainment distributions by the observed ENADID/ENE proportions of male and female migrants. The predicted educational distributions of all migrants are those shown in Table 3. The alternate predicted educational distributions of all migrants when the MxFLS is used as the auxiliary data source from which the γ1k and γ2k coefficients are estimated are shown in [SELF-INDENTIFYING REFERENCE, Appendix Table A2.3].

REFERENCES

- Aleksynka Mariya, Tritah Ahmed. Occupation-education mismatch of immigrant workers in Europe: Context and policies. Economics of Education Review. 2013;36:229–244. [Google Scholar]

- Ambrosini J. William, Peri Giovanni. The determinants and the selection of Mexico-U.S. migrants. The World Economy. 2012;35(2):111–151. [Google Scholar]

- Antecol Heather, Cobb-Clark Deborah A., Trejo Stephen J. Immigration policy and skills of immigrants to Australia, Canada, and the United States. Journal of Human Resources. 2003;38:192–218. [Google Scholar]

- Anzaldo Carlos, Barron. Eric A. La transición urbana de México, 1900-2005 [Mexico’s urban transition, 1900-2005] 2009 La Situación Demográfica de México www.conapo.gob.mx Accessed 2/2/10.

- Bauer Thomas, Pereira Pedro T., Vogler Michael, Zimmermann Klaus F. Portuguese migrants in the German labor market: Selection and performance. International Migration Review. 2002;36(2):467–491. [Google Scholar]

- Bellettini Giorgio, Ceroni Carlotta Berti. Immigration policy, self-selection, and the quality of immigrants. Review of International Economics. 2007;15(5):869–877. [Google Scholar]

- Belot Michele V.K , Hatton Timothy J. Immigrant selection in the OECD. Scandanavian Journal of Economics. 2012;114(4):1105–1128. [Google Scholar]

- Bianchi Milo. Immigration policy and self-selecting migrants. Journal of Public Economic Theory. 2013;15(1):1–23. [Google Scholar]

- Bilsborrow Richard E ., Hugo Graeme, Oberai Amarjit, Zlotnik Hania. International Migration Statistics: Guidelines for Improving Data Collection Systems. International Labour Office; Geneva: 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Borjas George J. Self-Selection and the earnings of immigrants. American Economic Review. 1987;77:531–53. [Google Scholar]

- Borjas George J. Assimilation and changes in cohort quality revisited: What happened to immigrant earnings in the 1980s? Journal of Labor Economics. 1995;13(2):201–245. doi: 10.1086/298373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campos-Vasquez Raymundo M., Lara Jaime. Self-selection patterns among return migrants: Mexico 1990-2010. IZA Journal of Migration. 2012;1:8. [Google Scholar]

- Cerrutti Marcela, Massey Douglas S. On the auspices of female migration from Mexico to the U.S. Demography. 2001;38(2):187–200. doi: 10.1353/dem.2001.0013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiquiar Daniel, Hanson Gordon H. International migration, self-selection, and the distribution of wages: Evidence from Mexico and the United States. Journal of Political Economy. 2005;113(2):239–281. [Google Scholar]

- Chiswick Barry R. Are immigrants favorably self-selected? American Economic Review. 1999;89(2):181–185. [Google Scholar]

- CONAPO . ,Índices de intensidad migratoria México-Estados Unidos 2010. In: Jorge Durand, Massey Douglas S., editors. Crossing the Border: Research from the Mexican Migration Project. Russell Sage Foundation; New York: 2012. 2004. [Indicators of Mexico-U.S. Migration Intensity 2010] www.conapo.gob.mx. [Google Scholar]

- Durand Jorge, Massey Douglas S., Zenteno Rene M. Mexican immigration to the United States: Continuities and changes. Latin American Research Review. 2001;36(1):107–127. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feliciano Cynthia. Educational selectivity in U.S. immigration: How do immigrants compare to those left behind? Demography. 2005;42(1):131–152. doi: 10.1353/dem.2005.0001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feliciano Cynthia. Gendered selectivity: U.S. Mexican immigrants and Mexican nonmigrants, 1960-2000. Latin American Research Review. 2008;43(1):139–160. [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez-Huertas Moraga Jesus. New evidence on emigrant selection. Review of Economics and Statistics. 2011;93(1):72–96. [Google Scholar]

- Fussell Elizabeth. Sources of Mexico's Migration Stream: Rural, Urban, and Border Migrants to the United States. Social Forces. 2004;82(3):937–967. [Google Scholar]

- Garip Filiz. Discovering diverse mechanisms of migration: The Mexico-U.S. stream 1970-2000. Population and Development Review. 2012;38(3):393–433. [Google Scholar]

- Hall Matthew, Greenman Emily, Farkas George. Legal status and wage disparities for Mexican immigrants. Social Forces. 2010;89(2):491–514. doi: 10.1353/sof.2010.0082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grogger Jeffrey, Hanson Gordon H. Income maximization and the selection and sorting of international migrants. Journal of Development Economics. 2011;95:42–57. [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton Erin R., Villarreal Andrés. Development and the urban and rural geography of Mexican migration to the United States. Social Forces. 2011;90(2):661–683. [Google Scholar]

- Hanson Gordon H. Illegal migration from Mexico to the United States. Journal of Economic Literature. 2006;44:869–924. [Google Scholar]

- Hill Kenneth, Wong Rebeca. Mexico-U.S. migration: Views from both sides of the border. Population and Development Review. 2005;31(1):1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Ibarraran Pablo, Lubotsky Darren. Mexican Immigration and Self-selection: New Evidence from the 2000 Mexican Census. In: Borjas George J., editor. Ch.7 in Mexican Immigration to the United States. University of Chicago Press; Chicago: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- INEGI [Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía] Síntesis Metodológica de la Encuesta Nacional de la Dinámica Demográfica [National Survey of Demographic Dynamics] www.inegi.gob.mx. 2003 www.inegi.gob.mx

- INEGI [Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía] Módulo sobre Migración 2002. Encuesta Nacional de Empleo (ENE) [Migration Module 2002: National Survey of Employment] México; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- INEGI [Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía] Encuesta Nacional de Ocupacion y Empleo (ENOE) 2005 [National Survey of Occupation and Employment] www.inegi.gob.mx.

- Kaestner Robert, Malamud Ofer. Self-selection and international migration: New evidence from Mexico. Review of Economics and Statistics. 2013 [Google Scholar]

- Kana’iaupuni Shawn Malia. Reframing the migration question: An analysis of men, women, and gender in Mexico. Social Forces. 2000;78(4):1311–1348. [Google Scholar]

- Kandel William, Massey Douglas S. The culture of migration: A theoretical and empirical analysis. Social Forces. 2002;80(3):981–1004. [Google Scholar]

- Landale Nancy S., Oropesa R. Salvador, Llanes Daniel. Schooling, work, and idleness among Mexican and non-Latino white adolescents. Social Science Research. 1998;27:457–480. [Google Scholar]

- Liebig Thomas, Sousa-Poza Alfonso. Migration, self-selection and income inequality: An international analysis. Kyklos. 2004;57:125–146. [Google Scholar]

- Lindstrom David P., Massey Douglas S. Selective emigration, cohort quality, and models of immigrant assimilation. Social Science Research. 1994;23:315–349. [Google Scholar]

- Marcelli Enrico A., Cornelius Wayne A. The changing profile of Mexican migrants to the US: New evidence from California and Mexico. Latin American Research Review. 2001;36(3):105–131. [Google Scholar]