Abstract

A pelvic fracture urethral distraction defect (PFUDD) can present in varying lengths and degrees of complexity. In recent decades the repair of PFUDD has developed into a reliance on a perineal anastomotic approach for all but the most complex cases, which might still require an abdominal transpubic approach, or rarely a staged skin-inlay procedure. There is now controversy about the extent to which the perineal repair needs to be elaborated in individual patients. As originally described, the elaborated perineal approach comprises four steps that are used sequentially, as required, depending on the magnitude of the urethral defect. These steps are urethral mobilisation, corporal body separation, inferior wedge pubectomy and supra-crural urethral re-routing to the anastomosis. We present a review of the progressive repair, its reported use and outcomes and our recommendations for its continued use.

Abbreviations: PFUDD, pelvic fracture urethral distraction defect

Keywords: Pelvic fracture, Urethral distraction defect, Simple perineal posterior, Elaborated, Urethroplasty

Introduction

Previous reports suggested that urethral injury occurs in ≈10% of pelvic fractures, but the relative infrequency of these injuries in modern practice raises questions about this incidence [1,2]. A more accurate value might be that quoted by Andrich et al. [3], that is based on UK Department of Health statistics. Over a recent 3-year period there was a mean of 6349 pelvic fractures, with 159 associated with a urethral injury, giving an incidence of 2.5%.

We will not discuss the history of nor the current controversy about the initial management of these injuries, which at present can be summarised as either early (delayed-primary) urethral realignment using a variety of techniques, or delayed surgical urethroplasty at 3–6 months, after the initial placement of a suprapubic catheter alone. Regardless of the initial management there will be men who develop an obliterative posterior urethral defect, referred to as a posterior urethral distraction defect (PFUDD), for which reconstruction will be necessary.

The surgical repair of these defects has a rich history, with reports dating back to the 1950s. Amongst the earliest techniques reported was that of Badenoch [4] who described a urethral pull-through procedure for impassable traumatic stricture. This was an unsutured repair where the proximal end of the bulbar urethra, attached to a catheter, was drawn through the cored pelvic scar, to heal itself to the prostatic urethra. Modern variations of this technique continue to be described and generally used in salvage circumstances. Also in the early 1950s, a staged scrotal-inlay procedure was reported for the repair of urethral strictures in general, but adapted also to the management of the PFUDD [5]. Many variations of this technique were developed over the ensuing decade, all adhering to the principle of deployment of scrotal skin through the stricture in the first stage, followed by tubularisation of the skin into a neourethra in the second [6,7].

Johanson [5] reported his concerns with immediate intervention and realignment for PFUDD, because of the high operative morbidity and mortality rates, erectile dysfunction and incontinence, and he fuelled the enthusiasm for initial suprapubic catheter management with delayed urethroplasty using one of the aforementioned techniques. Others later reported similar concerns [8–10].

While the staged scrotal-inlay approach continued to be favoured for the secondary repair of PFUDDs throughout this era, others described improved access to the proximal urethra using abdominal pubectomy [11,12].

This led to an enthusiasm for delayed anastomotic repairs by an abdomino-perineal approach, championed by Waterhouse et al. [13] and separately by Richard Turner-Warwick [14]. Their approaches differed in that the Waterhouse procedure was used in all patients with a PFUDD and entailed removing an entire wedge of anterior pubis, commonly using a Gigli saw. Turner-Warwick only resorted to pubectomy if he could not make the anastomosis perineally, and only removed a portion of the abdominal surface of the pubis, sufficient to gain access to the apex of the prostate.

Turner-Warwick’s treatise on the subject was a landmark publication [14], and presented an approach to the PFUDD in which the complexity of the injury was considered and the nature of associated defects that might indicate the need for posterior pubectomy. It was an era in which complicating features such as associated pelvic abscess, urethro-rectal, urethro-cutaneous and complex bladder-base fistulae were not uncommon, all of which would require an abdomino-perineal approach, facilitated by pubectomy. Often these problems were iatrogenically induced by the treatment given during the patient’s acute care and later attempts at management. Also, and more importantly, abdominal exposure with pubectomy was deemed necessary for urethral defects of >2 cm long, which comprised a significant number of cases [15–17].

In 1985, the present author (Webster) reported a procedural variation that avoided abdominal exposure and pubectomy for long urethral defects, entailing only a limited wedge excision of the inferior portion of the pubis via the perineum, this after separating the posterior aspect of the corporeal bodies for 3–5 cm. This limited inferior pubectomy allowed for improved perineal exposure of the apex of the prostate for anastomosis, and allowed the bulbar urethra to take a more direct route, reducing anastomotic tension [18].

Using this approach we were able to repair defects of 5 cm long via the perineum alone. A few years later this was followed by adding a further manoeuvre, supra-corporal re-routing, to address even the longest defects perineally. This procedure became known as the ‘elaborated perineal approach’ [19].

By this time, staged scrotal-skin inlay procedures were uncommon for PFUDDs and reconstruction was generally by this perineal anastomotic repair or by the Waterhouse approach [20–22].

Despite this ability to now address even the longest defects, an abdomino-perineal approach can still be necessary to address the intrapelvic complicating features, such as bladder base fistula, pelvic floor cavity and some patients with a urethrorectal fistula [23].

Methods

Patient selection and preparation

The repair is delayed until 3–6 months after the initial injury, the patient having been managed in the interim with a suprapubic catheter. Preoperative studies include a combined retrograde urethrogram and voiding cysto-urethrogram (an ‘up-and-down-o-gram’) that hopefully shows the length of the defect and any other complicating features such as fistula or periurethral cavity. The use of MRI has been reported but we have found no use for this. Flexible endoscopy of the urethra and bladder via the suprapubic tract is uncommon before surgery, but is used during surgery to evaluate the proximal urethral stump in cases where this did not fill radiographically.

Procedural summary

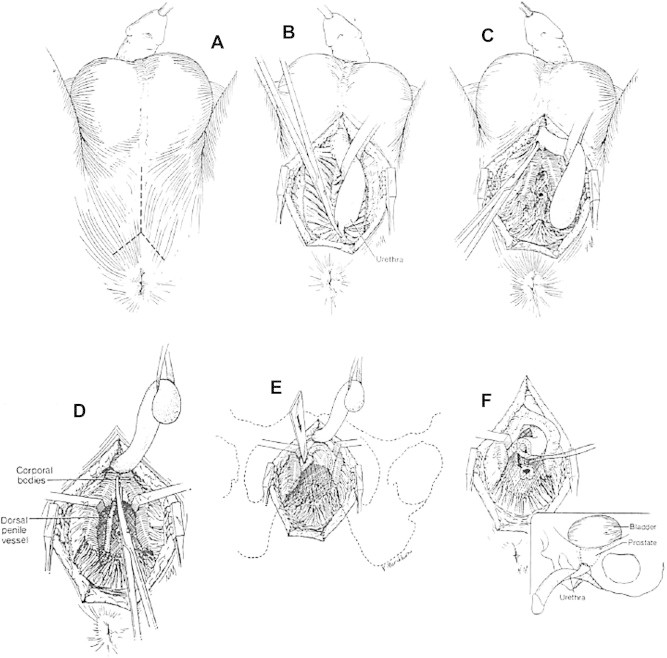

The procedure, performed through the perineum, aims to achieve a tension-free bulboprostatic urethral anastomosis using the fewest elaborating steps [19] (Fig.1 and Table1). Step 1 alone describes a simple perineal approach, which many report to be adequate for all defects. Step 2 adds corporal-body separation to shorten the distance to the anastomosis and is the next step in the ‘elaborated perineal approach’. Step 3 includes steps 1 and 2 and adds inferior pubectomy that shortens the distance further and, importantly, improves visibility and access to the apex of the prostate. Step 4 adds to steps 1, 2 and 3 and re-routes the urethra around the left corporal body, further shortening the distance to the anastomosis and so reducing anastomotic tension, and in our experience allowing for an anastomotic repair in defects as long as 9 cm. It is potential anastomotic tension that leads the surgeon to move up the ladder of steps.

Figure 1.

(A) A short midline perineal incision bifurcated posteriorly gives improved access to the membranous urethra. (B) The urethra is circumferentially mobilised proximally to the point of obliteration and distally to the crus. Incision of the posterior attachments and urethra facilitates the access. (C) The urethra is transected at the point of obliteration and mobilised distally beyond the crus. (D) The corporal body is separated in bloodless planes from the crus distally for 4–5 cm. Separation beyond this point is generally not possible. (E) An inferior pubectomy using osteotomes. Only a small channel of the bone requires removal between the separated corporal bodies. (F) Supra-crural re-routing of the urethra mobilised only as far as the suspensory ligament allows it to course to the high-riding prostate. From [19], with permission.

Table 1.

Manoeuvres used and the results of perineal repairs in 74 patients. Adapted from [19], with permission.

| Manoeuvres for repair | N patients | Mean (range) length (cm) | Success n/N or n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Urethral mobilisation | 8 | 1.75 (1.5–2.0) | 8/8 |

| Corporal separation | 33 | 2.5 (1.5–4.5) | 32 (91) |

| Inferior pubectomy | 22 | 3.0 (1.5–6.5) | 21 (93) |

| Urethral re-routing | 11 | 4.75 (2.0–7.0) | 10/11 |

| Total | 74 | – | 71 (96) |

Step 1: Urethral mobilisation alone

Used alone, this step describes the ‘simple perineal posterior urethroplasty’. We prefer a midline perineal incision bifurcated posteriorly. The bulbar urethra is circumferentially mobilised from the point of proximal obliteration, where it is transected, distally as far as the suspensory ligament of the penis. Essentially the urethra is now a distally based flap relying on retrograde blood flow from the glans and remaining corporal perforating vessels. Any previous injury or surgery to the urethra potentially jeopardises the survivability of the flap, as also might any anastomotic tension. The proximal urethral stump is identified through the scarred pelvic floor scar by palpating for and cutting down onto the tip of a descending urethral sound passed through the suprapubic tract and negotiated through the bladder neck down to the obliteration. Generally speaking, the tip is palpated more posterior than expected, as this is the more frequent direction of prostatic dislocation. In cases where a long urethral defect precludes palpation of the tip of the sound, the scar is incised in the midline, judiciously excising scar until the sound is encountered. The proximal urethra is then dissected carefully until mucosa is evident circumferentially, at which point the urethra is spatulated posteriorly, often as far proximal as the verumontanum. The bulbar urethra is spatulated on its opposing side, and if tension-free approximation is possible the anastomosis is made using radial 4–0 polyglycolic acid sutures. The anastomosis is facilitated by a long-bladed nasal speculum, and sutures are placed using a needle bent into a J-shape and a ‘push in-pull out’ technique. The anastomosis is stented with a 12–16 F silicone catheter for 14–21 days and the suprapubic tube is replaced. Anastomotic healing is confirmed by a pericatheter urethrogram before removal. In our experience, this manoeuvre alone is sufficient for defect lengths of ⩽2 cm.

Step 2: Corporal body separation

If after step 1 a tension-free anastomosis cannot be achieved the urethra can be mobilised a little further (not beyond the penoscrotal junction) and routed between the posteriorly separated corporal bodies. This separation is in a bloodless plane for ≈5 cm. This manoeuvre, cutting the corner to the anastomosis, generally gains an extra centimetre of urethral length. The anastomosis is then made as described above.

Step 3: Inferior wedge pubectomy

If the anastomosis still seems to be under tension because of a high-lying prostate, step 3 is used, a wedge excision of the inferior pubic arch. The undersurface of the bone will have been exposed by the corporal separation, and after displacement or ligation of the vascular structures the small wedge of the bone is easily removed using an osteotome/Capener’s gouge and bone rongeurs. This manoeuvre allows the urethra to be routed much more directly to the spatulated apex of the prostatomembranous urethra, considerably shortening the distance and significantly improving the access and visibility for suture placement.

Step 4: Supracrural re-routing

This is our final step to achieve a tension-free anastomosis should the first three steps not suffice. The urethra is routed around the lateral side of the left corporal body and then through the bony defect created by the earlier inferior pubectomy. This changes the ‘swing point’ of the urethral flap, reducing further the distance to the anastomosis. A small furrow of the bone should be gouged from the pubis where the urethra runs, to avoid its compression between the corpus and bone.

Discussion

In the early 1980s Turner-Warwick had codified the management of the short PFUDD, using a perineal approach alone, and that of the longer (>2 cm) or complex defect by an abdomino-perineal approach [13]. To some degree the advised avoidance of a perineal approach for defects of >2 cm in that era was probably a consequence of the poorer results in that group, and a reluctance to excessively mobilise the distal urethral for fear of urethral survival or causing penile chordee. When the present author (G.D.W.) first reported the transperineal inferior pubectomy, and a few years later the addition of supracrural re-routing, these steps were advocated to address the long defect by a less morbid perineal approach [18,19].

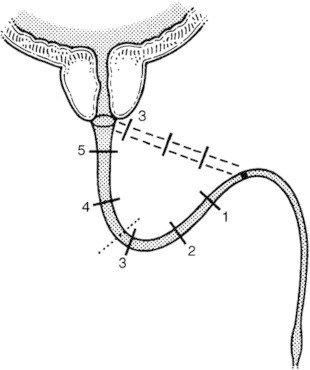

The basis for the progressive elaborated perineal approach is to alter the geometry of the path needed to approximate the bulbar urethral end to the dislocated proximal urethral stump. Achieving this goal relies on a healthy elastic distal (bulbar) urethra. Any compromise to this due to previous injury or surgery, etc., can significantly reduce the ability to perform a ‘simple perineal approach’. Some pelvic fracture injuries to the urethra are associated with ‘die back’ of some of the bulb, leading to a markedly more difficult procedure, as some of the more elastic portion of the bulb needed for repair is lost. Injudicious and excessive attempts at early endoscopic repair are also a cause of this event [24]. Cases in which a tension-free anastomosis by urethral mobilisation alone is insufficient are those for which the progressive elaborated approach is relevant. Mundy [25] elegantly described and illustrated how the procedure might achieve its goals (Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

When straightening curves between the bulbo-pendulous junction and prostate apex, the bulbar urethra follows the diameter rather than the circumference of the curve, and therefore helps to bridge the PFUDD. From [25], with permission.

Koraitim [26] reported using clinico-radiological variables, including a ‘gapometry’/urethrometry index, urethral gap length and prostate displacement, to predict which patients might be manageable by a simple perineal urethroplasty alone and which would require an elaborated perineal or transpubic approach.

We have always felt that the surgeon repairing a PFUDD should be capable of performing all the steps used in the progressive elaborated approach, for we have often found that a seemingly simple-looking defect on preoperative radiographs might prove to be vastly different on surgical exploration. This was also reported by Andrich et al. [27], who assessed 100 men undergoing repair for the first time. In 38 men there was no visualisation of the urethra below the bladder neck on the preoperative radiographs, and so the defect length could not be determined. In the remaining 62 men there was no association of the measured defect length and the scale of surgery required. They concluded that the surgeon repairing a PFUDD must be willing and able to comfortably perform all four of the steps described. In that series, seven men were repaired using urethral mobilisation alone, 35 needed addition crural separation, seven an inferior pubectomy and 51 urethral re-routing [17]. These data are remarkably similar to ours, as published in our second reported series [28] (Table 2).

Table 2.

A comparison of the estimated length of the urethral defect on preoperative fluoroscopy vs. the number of steps used in perineal repairs. Adapted from [28], with permission.

| Step |

n (%) for length (cm) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ⩽3 | >3 | Unknown | Total | |

| N patients | 72 | 20 | 30 | 122 |

| 1 | 7 (10) | 1 (5) | 2 (7) | 10 (8) |

| 2 | 28 (39) | 4 (20) | 10 (33) | 42 (34) |

| 3 | 8 (11) | 2 (10) | 5 (17) | 15 (12) |

| 4 | 25 (35) | 12 (60) | 9 (30) | 46 (38) |

| Information not available | 4 (6) | 1 (5) | 4 (13) | 9 (7) |

Others have reported their approach for correcting the PFUDD. Koraitim [23,29,30] has been a prolific and observant reporter of his ongoing experience and of procedure selection and outcomes from a less developed nation.

Singh et al. [31] reported their successful use of the progressive elaborated perineal approach in 172 patients, with an overall success rate of 91%; they only used re-routing in 2% of patients.

Fu et al. [32] reported a series of 301 patients, with 263 (87.4%) successes. Simple perineal anastomosis was used in 103 (34.2%), perineal anastomosis with separation of the corporal bodies in 89 (29.6%), perineal anastomosis with inferior pubectomy in 95 (31.6%) and perineal anastomosis with re-routing of the urethra around the corpora cavernosum in 14 (4.7%). Of the 301 delayed transperineal bulboprostatic anastomosis procedures, 263 (87.4%) were successful and 38 (12.6%) were unsuccessful. Simple perineal anastomosis with no ancillary procedures had an 89.3% success rate, perineal anastomosis with separation of the corporeal body an 86.5% success rate, perineal anastomosis with inferior pubectomy an 84.2% success rate, and perineal anastomosis with urethral re-routing an 85.7% success rate.

Others have reported less reliance on the approach to repair the PFUDD. Kizer et al. [33], reporting a compilation review of 142 patients from five surgeons in five different centres, concluded that “ancillary manoeuvres such as corporal splitting or inferior pubectomy are seldom required for successful posterior urethral reconstruction and that urethral re-routing appears to be inferior to the abdominoperineal approach as a salvage manoeuvre for complex cases”.

While there is an infrequent use of supracrural re-routing in each of these small series, it is probably an overstatement to consider it an ‘almost never necessary’ procedure for all. Case profiles differ amongst centres and our referral pattern was to receive more complex cases and repeat cases, which might account for our need for more elaborated repairs. This is also true of cases reported by Mundy’s group, who had a 38% use of corporal re-routing. It would be a mistake to disregard this technique, with its widely reported success, and to deem it rarely necessary, as what frequently substitutes for it is an abdomino-perineal approach which carries far greater morbidity. Kizer et al. also quote; “In contrast, groups at other reconstructive centres noted that urethral re-routing is almost wholly unnecessary”. Instead, they found that liberal urethral mobilisation and corporal splitting alone are sufficient, when needed, to enable a successful posterior urethral reconstruction in most patients. They reference MacAnich’s series reported by Morey [20] in which of 82 patients, 30 (37%) required pubectomy, most performed abdominally, to complete the anastomosis. In a further series quoted as supporting the lack of necessity for urethral re-routing they quote Koraitim [34], but he states that of 155 patients undergoing repair, 42 required pubectomy, and of these 37 were re-routed supracorporally. Koraitim used an abdomino-perineal pubectomy with re-routing while we were able to accomplish the same outcome via the perineum alone.

Given the increasing infrequency of pelvic fracture urethral injury in the developed world, and considering the complexity of the repair, it is likely that few surgeons will have sufficient exposure to these procedures to gain or maintain proficiency [3]. This is likely to lead to an increased use of attempted endoscopic management, which frequently complicates a later repair. Failed primary repairs, which presumably already entailed urethral mobilisation and even corporal separation, will become more common and the salvage procedure will probably require elaboration by inferior pubectomy and supracorporal re-routing, which we believe is a superior alternative to abdomino-perineal pubectomy or a staged repair. The salvage surgeon will require the entire array of urethral reconstructive techniques [35,36].

Amongst the most difficult cases are PFUDD injuries in pre-adolescent boys. Relatively speaking, a short defect acts as if much longer, as the poorly developed bulbar urethra lacks length and elasticity. Orabi [37] reported a large series of 78 children and described the use of an extensive perineal pubectomy for the difficult cases.

Aggarwal et al. [38] reported a large series of 34 boys (23 primary and 12 referred repeat cases) managed in part by a progressive perineal approach elaborated into an abdominal approach should an anastomosis not be possible by the first three steps alone. They did not add supracrural re-routing to the inferior pubectomy, preferring to expose for an anastomosis abdominally where necessary (50% of primary and 90% of repeat cases). Salvage substitution repairs were needed in seven boys using a variety of techniques. The outcomes were successful in 95% of primary but only 41% of repeat cases. Indeed, the difficulties that this group present have led to the use of inventive techniques such as a sagittal approach to anastomosis [39,40].

Conclusions

As originally described, the four-step progressive/elaborated approach to the repair of PFUDD was a means to avoid the need for abdomino-perineal approaches or staged repairs for long urethral defects. It did not replace the need for an abdominal approach for what is now an uncommon incidence of associated intra-abdominal pathology. The technique was embraced and is still widely reported, with success in large series. In recent years in the USA there has been a move to minimise the steps required to achieve a tension-free anastomosis, primarily by avoiding supracrural re-routing of the urethra. This has become a ‘rallying cry’ in presentations which might in some circumstances be appropriate. The magnitude of injuries has reduced and the acceptance for more urethral mobilisation and anastomotic tension hopefully will prove to be borne out by good results. Nonetheless, the repertoire of the urethral reconstructive surgeon should include the entire array of manoeuvres, particularly in regions where the injuries are more extravagant and when the alternative might be an acceptance of excessive anastomotic tension or conversion to a more morbid abdomino-perineal approach.

Conflict of interest

None.

Source of funding

None.

Footnotes

Peer review under responsibility of Arab Association of Urology.

References

- 1.Glass R.E., Flynn J.T., King J.B., Blandy J.P. Urethral injury and fractured pelvis. Br J Urol. 1978;50:578–582. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410x.1978.tb06216.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Koraitim M.M. Pelvic fracture urethral injuries: the unresolved controversy. J Urol. 1999;161:1433–1441. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Andrich D.E., Greenwell T.J., Mundy A.R. Treatment of pelvic fracture-related urethral trauma: a survey of current practice in the UK. BJU Int. 2005;96:127–130. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2005.05580.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Badenoch A.W. A pull-through operation for impassable traumatic stricture of the urethra. Br J Urol. 1950;22:404–409. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410x.1950.tb02547.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Johanson B. Reconstruction of the male urethra and strictures. Acta Chir Scand. 1953;176:3–88. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Turner-Warwick R. The repair of urethral strictures in the region of the membranous urethra. J Urol. 1968;100:303–314. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)62525-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Leadbetter G.W., Jr. A simplified urethroplasty for strictures of the bulbous urethra. J Urol. 1960;83:54–59. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5347(17)65654-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Webster G.D., Mathes G.L., Selli C. Prostatomembranous urethral injuries. A review of the literature and a rational approach to their management. J Urol. 1983;130:898–902. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)51561-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Morehouse D.D., Belitsky P., Mackinnon K. Rupture of the posterior urethra. J Urol. 1972;107:255–258. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)60996-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Morehouse D.D., Mackinnon K.J. Management of prostatomembranous urethral disruption: 13-year experience. J Urol. 1980;123:173–174. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)55839-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pierce J.M., Jr. Exposure of the membranous and posterior urethra by total pubectomy. J Urol. 1962;88:256–258. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5347(17)64779-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Paine D., Coombes W. Transpubic reconstruction of the urethra. Br J Urol. 1968;40:78–84. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410x.1968.tb11816.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Waterhouse K., Abrahams J.I., Gruber H., Hackett R.E., Patil U.B., Peng B.K. The transpubic approach to the lower urinary tract. J Urol. 1973;109:486–490. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)60459-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Turner-Warwick R. Complex traumatic posterior urethral strictures. J Urol. 1977;118:564–574. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)58109-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Webster G.D., Sihelnik S. The management of strictures of the membranous urethra. J Urol. 1985;134:469–473. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)47243-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Turner-Warwick R. Complex traumatic posterior urethral strictures. Trans Am Assoc Genitourin Surg. 1976;68:60–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Turner-Warwick R. A personal view of the immediate management of pelvic fracture urethral injuries. Urol Clin North Am. 1977;4:81–93. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Webster G.D., Goldwasser B. Perineal transpubic repair: a technique for treating post-traumatic prostatomembranous urethral strictures. J Urol. 1986;135:278–279. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)45609-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Webster G.D., Ramon J. Repair of pelvic fracture posterior urethral defects using an elaborated perineal approach: experience with 74 cases. J Urol. 1991;145:744–748. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)38442-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Morey A.F., McAninch J.W. Reconstruction of traumatic posterior urethral strictures. Tech Urol. 1997;3:103–107. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mcaninch J.W. Pubectomy in repair of membranous urethral stricture. Urol Clin North Am. 1989;16:297–302. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ennemoser O., Colleselli K., Reissigl A., Poisel S., Janetschek G., Bartsch G. Posttraumatic posterior urethral stricture repair. Anatomy, surgical approach and long-term results. J Urol. 1997;157:499–505. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(01)65187-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Koraitim M.M. Complex pelvic fracture urethral distraction defects revisited. Scand J Urol. 2014;48:84–89. doi: 10.3109/21681805.2013.817484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tausch T.J., Morey A.F., Scott J.F., Simhan J. Unintended negative consequences of primary endoscopic realignment for men with pelvic fracture urethral injuries. J Urol. 2014;192:1720–1724. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2014.06.069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mundy A.R. Reconstruction of posterior urethral distraction defects. Atlas Urol Clin N Am. 1997;5:139–143. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Koraitim M.M. Predictors of surgical approach to repair pelvic fracture urethral distraction defects. J Urol. 2009;182:1435–1439. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2009.06.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Andrich D.E., O’Malley K.J., Summerton D.J., Greenwell T.J., Mundy A.R. The type of urethroplasty for a pelvic fracture urethral distraction defect cannot be predicted preoperatively. J Urol. 2003;170:464–467. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000076752.32199.40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Flynn B.J., Delvecchio F.C., Webster G.D. Perineal repair of pelvic fracture urethral distraction defects: experience in 120 patients during the last 10 years. J Urol. 2003;170:1877–1880. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000091642.41368.f5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Koraitim M.M. Transpubic urethroplasty revisited: total, superior, or inferior pubectomy? Urology. 2010;75:691–694. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2009.09.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Koraitim M.M. Failed posterior urethroplasty: lessons learned. Urology. 2003;62:719–722. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(03)00573-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Singh S.K., Pawar D.S., Khandelwal A.K., Jagmohan Transperineal bulboprostatic anastomotic repair of pelvic fracture urethral distraction defect and role of ancillary maneuver: a retrospective study in 172 patients. Urol Ann. 2010;2:53–57. doi: 10.4103/0974-7796.65104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fu Q., Zhang J., Sa Y.L., Jin S.B., Xu Y.M. Transperineal bulboprostatic anastomosis in patients with simple traumatic posterior urethral strictures: a retrospective study from a referral urethral center. Urology. 2009;74:1132–1136. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2009.05.078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kizer W.S., Armenakas N.A., Brandes S.B., Cavalcanti A.G., Santucci R.A., Morey A.F. Simplified reconstruction of posterior urethral disruption defects: limited role of supracrural rerouting. J Urol. 2007;177:1378–1381. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2006.11.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Koraitim M.M. On the art of anastomotic posterior urethroplasty: a 27-year experience. J Urol. 2005;173:135–139. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000146683.31101.ff. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Webster G.D., Ramon J., Kreder K.J. Salvage posterior urethroplasty after failed initial repair of pelvic fracture membranous urethral defects. J Urol. 1990;144:1370–1372. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)39744-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bhagat S.K., Gopalakrishnan G., Kumar S., Devasia A., Kekre N.S. Redo-urethroplasty in pelvic fracture urethral distraction defect: an audit. World J Urol. 2011;29:97–101. doi: 10.1007/s00345-010-0524-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Orabi S. Transpubic posterior urethroplasty via perineal approach in children: a new technique. J Pediatr Urol. 2012;8:393–400. doi: 10.1016/j.jpurol.2011.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Aggarwal S.K., Sinha S.K., Kumar A., Pant N., Borkar N.K., Dhua A. Traumatic strictures of the posterior urethra in boys with special reference to recurrent strictures. J Pediatr Urol. 2011;7:356–362. doi: 10.1016/j.jpurol.2011.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Onofre L.S., Leao J.Q., Gomes A.L., Heinisch A.C., Leao F.G., Carnevale J. Pelvic fracture urethral distraction defects in children managed by anterior sagittal trans anorectal approach. A facilitating and safe access. J Pediatr Urol. 2011;7:349–355. doi: 10.1016/j.jpurol.2011.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Canning D.A. Re: pelvic fracture urethral distraction defects in children managed by anterior sagittal trans anorectal approach: a facilitating and safe access. J Urol. 2013;189:312. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2012.09.131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]