Abstract

Background

Lactoferrin (LF) is a broad-spectrum antimicrobial and immunomodulatory milk glycoprotein.

Objective

To determine the effect of bovine LF on the prevention of the first episode of late-onset sepsis in Peruvian infants.

Methods

We conducted a pilot randomized placebo-controlled double blind study in infants with a birth weight <2500g in three Neonatal Units in Lima. Patients were randomized to receive bovine LF 200mg/kg/day or placebo for four weeks.

Results

190 neonates with a birth weight of 1591±408g and a gestational age of 32.1±2.6wks were enrolled. Overall, 33 clinically-defined first late-onset sepsis events occurred. The cumulative sepsis incidence in the LF group was 12/95(12.6%) vs. 21/95(22.1%) in the placebo group, and 20% (8/40) vs. 37.5% (15/40) for infants ≤1500g. The hazard ratio of LF, after adjustment by birth weight, was 0.507 (95% CI, 0.249 to 1.034). There were 4 episodes of culture-proven sepsis in the LF group vs. 4 in the placebo group. Considering that children did not received the intervention until the start of oral or tube feeding, we ran a secondary exploratory analysis using time since the start of the treatment; in this model, LF achieved significance. There were no serious adverse events attributable to the intervention.

Conclusions

Overall sepsis occurred less frequently in the LF group than in the control group. Although the primary outcome did not reach statistical significance, the confidence interval is suggestive of an effect that justifies a larger trial.

Keywords: Bovine, preterm, newborn, infant, late-onset sepsis

INTRODUCTION

Four million neonates die each year, mostly in low-income countries1. The three major causes of neonatal death are asphyxia, infection, and complications of preterm birth, which account for 86% of deaths1. Globally almost one million newborns die due to infections (neonatal sepsis, pneumonia and meningitis)1. In developing countries, infection may be responsible for as many as 42% of deaths in the first week of life2. Up to 80% of newborn deaths are among low birth weight babies, most of whom are preterm1.

Multiple strategies have been designed to reduce infant mortality. Among these, breastfeeding is the most cost-effective intervention for protection from infection and prevention of all causes of infant mortality3. Breast milk has a beneficial effect in term and preterm infants including improved cognitive and behavior skills, and decreased rates of infection4- 7. The protective effects of human milk are thought to be due to multiple anti-infective, anti-inflammatory, and immunoregulatory factors8,9. We hypothesize that lactoferrin (LF) is the major milk factor responsible for decreased rates of infection due to its antimicrobial and immunomodulatory properties10. Recently, 472 very low-birth-weight infants (VLBW; birth weight <1500g) were randomly assigned to receive orally administered bovine LF, LF plus the probiotic Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG (LF+LGG), or placebo for 30 days11. The incidence of sepsis was significantly lower in the LF and LF+LGG groups compared with the placebo group (5.9% and 4.6% vs. 17.3%). Whether LF has an effect in higher risk populations in developing countries remains to be determined. Therefore, we conducted a hospital-based randomized placebo-controlled double blind study in 190 infants ≤2500g in Neonatal Units in Peru to determine whether bovine LF prevents the first episode of late-onset sepsis in neonatal setting from a low-income country.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Study design

We conducted a randomized double blind placebo-controlled clinical trial in neonates, comparing daily supplementation with bovine LF versus placebo administered for four weeks.

Study population

We included neonates with a birth weight between 500 and 2500g born in or referred in the first 72 hours of life to the Neonatal Intermediate and Intensive Care Units of one of the participating hospitals: Hospital Nacional Cayetano Heredia (Cayetano), Hospital Nacional Guillermo Almenara Irigoyen (Almenara), and Hospital Nacional Alberto Sabogal Sologuren (Sabogal). We excluded neonates with underlying gastrointestinal problems that prevent oral intake, predisposing conditions that profoundly affect growth and development (chromosomal abnormalities, structural brain anomalies, etc.), family history of cow milk allergy, neonates that lived far from Lima, and neonates whose parents declined to participate. Consecutive patients who qualified for the study were approached by the attending neonatologist who explained the study and obtained written informed consent from both parents before the 72-hour cut-off.

Randomization

Patients were assigned a consecutive study number in the order they were enrolled. The numbers were previously randomly assigned to the intervention with fixed, equal allocation to each group, stratified by weight (500–1000g, 1001–1500g, 1501–2000g and 2001–2500g), and randomized with block size of 4. This randomization list was prepared by a third party (not the clinical investigators) and was known only by the research pharmacist who prepared the weekly treatment packages based on neonates’ weight. Randomization occurred immediately after recruitment of each patient.

Intervention

Neonates received oral bovine LF (Tatua Co-operative Dairy Co, Ltd, Morrinsville, New Zealand) (200mg/kg/day in three divided doses each day) or placebo (maltodextrin, Montana S.A., Lima, Peru) (200mg/kg/day in three divided doses each day) for four weeks since the day of enrollment. The intervention product was composed of 97.1% bioactive protein of which 94.5% was LF, without additives. The iron saturation was 12%. Capsules containing LF or placebo were opened and mixed with whatever the neonates were taking orally or by tube at that time (breast milk, infant formula or dextrose); the intervention was given as soon as the patient started receiving any amount of oral or tube feedings. After discharge from the hospital, a research nurse visited the family weekly until the end of the first month of life. All children had a clinic visit at one and three months of chronological age.

Blinding

The physicians and study personnel were blinded to the treatment assignment throughout the study period. The data manager, statistician, and all investigators remained blinded to the group assignment until the end of the data analysis.

Study definitions

For this study, we determined the effect of LF on clinically-defined sepsis. We included both culture-proven sepsis and culture-negative clinical infection (probable or possible sepsis). Late-onset proven sepsis was defined by a positive blood culture and/or cerebrospinal fluid culture obtained after 72 hours of life in the presence of clinical signs and symptoms of infection12. Culture-negative clinical infection or “probable sepsis” was defined by the presence of clinical signs and symptoms of infection (temperature instability, heart rate > 2SD above normal for age, respiratory rate >60 breaths/min plus grunting or desaturations, lethargy/altered mental status, glucose intolerance defined as plasma glucose > 10mmol/L, feed intolerance, blood pressure < 2SD normal for age, capillary refill > 3 sec, plasma lactate > 3 mmol/L) and at least two abnormal inflammatory variables12: leukocytosis (WBC count >34,000 ×109/L), leukopenia (WBC count <5,000 ×109/L), immature neutrophils >10%, immature-to-total neutrophil ratio (I/T)>0.2, thrombocytopenia <100,000 ×109/L, and C-Reactive Protein (CRP) >10mg/dL or >2SD above normal. We have not measured procalcitonin, IL-6 or IL-8 or 16S PCR, which are other variables evaluated in Haque’s criteria. “Possible sepsis” was defined by the presence of clinical signs and symptoms of infection and raised CRP with negative blood culture. An independent diagnostic board reviewed all sepsis episodes.

Outcome

The primary outcome was risk of first episode of late-onset clinically-defined sepsis (culture-proven sepsis and culture-negative clinical infection) within 4 weeks (28 days) from enrollment. Secondary outcomes were frequency of culture-proven sepsis, pathogen-specific late-onset sepsis; necrotizing enterocolitis (NEC), duration of hospitalization, overall mortality rate, infection-related mortality, frequency of adverse events, and treatment intolerance.

Sample size

The reduction in sepsis episodes with LF supplementation was 66% in the Italian study11. Based on data from local neonatal units, we expected 30% of sepsis episodes in the placebo group during the 4-week follow up. Assuming 5% drop outs, 95 children were needed in each group to detect a 60% reduction in the number of sepsis episodes (α 0.05; power 0.80). We, therefore, planned to recruit 190 neonates.

Data management and analysis

Data were collected and then double entered into databases using EpiInfo v3.4.5. Data entry formats had predefined ranges for acceptable values. Consistency checks were performed in STATA v8.0. Statistical analysis was performed in STATA and R v3.0.2. P values from the Student’s t-test and Fisher’s exact test are presented for the univariate analysis comparing baseline demographic characteristics, risk factors, medical and surgical complications, and weight during follow up. Unadjusted relative risks as cumulative incidence ratios with their corresponding confidence intervals and p values were used to compare sepsis outcomes. Birth weight-adjusted relative risks were calculated using Generalized Linear Models (GLM). Cox proportional hazards regression model was applied for survival analysis. The primary outcome variable was the occurrence of the first episode of confirmed, possible or probable late-onset-sepsis, and time was counted as days from birth to that first episode or last day of follow-up, whichever happened first. The initial terms included were treatment group (TX), birth weight (BW in grams), hospital (HOS), peripartum maternal infection (dichotomous), age at start of follow-up, and the following interaction terms: TX:BW, TX:HOS, TX:BW:HOS, and BW:HOS. The model selection proceeded in four steps: initial set of terms, non-significant interaction terms removed, non-significant terms (except LF) removed and the final model, with removal of remaining non-significant terms.

Data Safety Monitoring Board (DSMB)

The DSMB, composed of an independent group of experts (neonatologists, pediatrician, epidemiologist, microbiologist), met every other month to review data for safety and study compliance. Any child experiencing a severe adverse event was referred to the DSMB for study continuation assessment.

Ethical and regulatory aspects

The study (www.clinicaltrials.gov:NCT01264536) was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Universidad Peruana Cayetano Heredia, University of Texas Health Science Center and by each of the three participating Hospitals. The study was also approved by the Peruvian Regulatory Institutions (INS and DIGEMID).

RESULTS

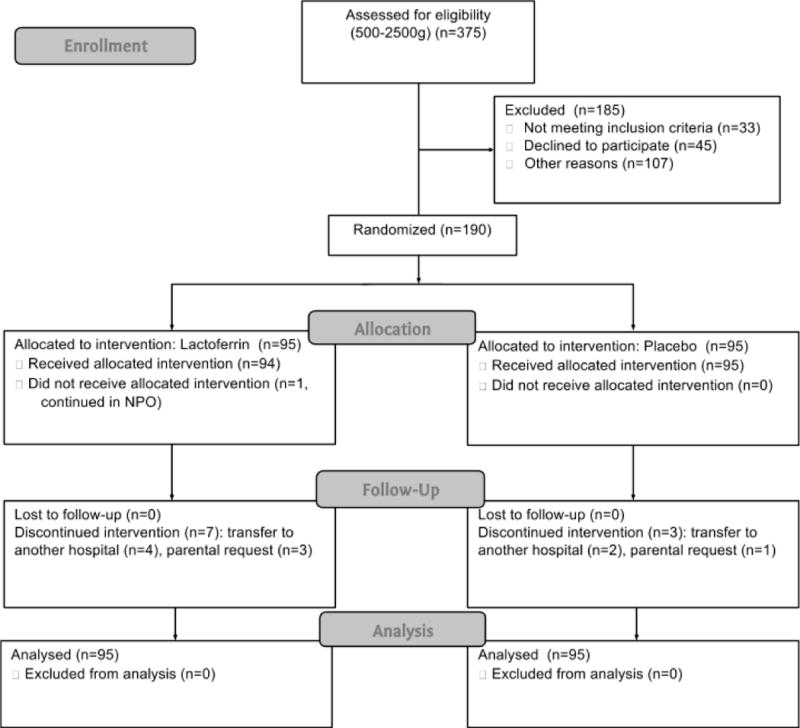

During the enrollment (January 31–August 6, 2011), 375 infants were assessed for eligibility, 185 were excluded (Figure 1). We enrolled 190 neonates; 80 (42.1%) had a birth weight <1500g. The gestational age was 32.1±2.6 weeks (26–38wks) and mean birth weight was 1591±408g. There were no significant baseline differences between groups in demographic and clinical characteristics or risk factors for late-onset sepsis (Table 1), except for peripartum maternal infections, which were more frequent in the placebo group, and more days of third and fourth-generation cephalosporin use in the placebo group. During the in-hospital follow up period nutritional characteristics were similar in both groups: approximately half of all days infants were fed only breast milk and approximately one third of days they were fed both infant formula and breast milk (Table 1). Additional information on the comparison between groups is presented in the supplementary data (Table S1)

Figure 1.

Study flow diagram. Enrollment: 375 neonates were assessed for eligibility. Allocation: 95 were randomized to LF and 95 to placebo; all received the allocated intervention. Follow-up: there were 7 and 3 drop-outs in the LF and placebo groups respectively. None were excluded from the analysis.

Table 1.

Comparison between Lactoferrin and Placebo Groups

| Lactoferrin | Placebo | p | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographic and clinical characteristics | ||||

| Peripartum maternal infection, n/total (%) | 10/91 (11.0) | 21/90 (23.3) | 0.031 | |

| Use of antibiotics on last month of pregnancy, n/total (%) | 19/90 (21.1) | 25/92 (27.2) | 0.389 | |

| Premature rupture of membranes, n/total (%) | 23/90 (25.6) | 25/94 (26.6) | 1.000 | |

| Chorioamnionitis, n/total (%) | 4/91 (4.4) | 10/91 (11.0) | 0.162 | |

| Cesarean delivery, n/total (%) | 81/95 (85.3) | 77/95 (81.1) | 0.561 | |

| Birth weight in g, mean ± SD (range) | 1582 ± 422 (770 – 2482) | 1600 ± 395 (710 – 2470) | 0.765 | |

| Gestational age in wks, mean ± SD (range) | 32.2 ± 2.6 (26 – 38) | 32.0 ± 2.6 (26 – 37) | 0.742 | |

| Small for gestational age, n/total (%) | 27/95 (28.4) | 23/95 (24.2) | 0.621 | |

| Neonatal resuscitation needed, n/l (%) | 27/93 (29.0) | 30/94 (31.9) | 0.751 | |

| Birth weight group distribution, n/total (%) | 1.000 | |||

| 500–1000 g | 9/95 (9.5) | 9/95 (9.5) | ||

| 1001–1500 g | 31/95 (32.6) | 31/95 (32.6) | ||

| 1501–2000 g | 40/95 (42.1) | 39/95 (41.1) | ||

| 2001–2500 g | 15/95 (15.8) | 16/95 (16.8) | ||

| Risk factors for late-onset sepsis and nutritional characteristics (first month of life or until discharge or withdrawal) * | ||||

| Time of initiation of oral feeding, DOL, mean ± SD | 3.1 ± 1.3 | 3.1 ± 1.6 | 0.964 | |

| Complete supplement administration in days, mean ± SD | 12.5 ± 8.1 | 13.9 ± 8.0 | 0.234 | |

| Nutritional characteristics, n (%) of child-days | 0.601 | |||

| NPO | 148 (9.6) | 161 (9.5) | ||

| Fed with only maternal milk | 765 (49.5) | 803 (47.3) | ||

| Fed with only formula | 154 (10.0) | 185 (10.9) | ||

| Fed with both formula and maternal milk | 480 (31.0) | 548 (32.3) | ||

| Central venous catheters positioned in days, mean ± SD | 4.9 ± 7.5 | 6.1 ± 8.6 | 0.294 | |

| Mechanical ventilation in days, mean ± SD | 0.9 ± 3.3 | 1.2 ± 4.1 | 0.557 | |

| Medication, days treated, mean ± SD | ||||

| Antibiotics | 4.9 ± 6.5 | 6.3 ± 7.5 | 0.168 | |

| Third/Fourth-generation cephalosporins | 0.4 ± 1.8 | 1.4 ± 3.7 | 0.018 | |

NICU, neonatal intensive care unit; DOL, day of life;

Lactoferrin: 1547 child-days; Placebo: 1697 child-days of observation.

The intervention was administered completely per protocol in 82% of 3,244 child-days of observation. It was started on average at 4.0 ± 1.4 days of life. Some neonates started the treatment a few days after enrollment because the treating neonatologist considered them too sick to tolerate any amount of oral or tube feeding. The diluents used in the 7,796 doses administered were breast milk in 67%, infant formula in 32% and dextrose in 1%. Ten patients (5.3%) were withdrawn from the study due to patients return to a distant province or transfer to a different hospital (n=6), or parental request (n=4).

Overall, there were 37 clinically-defined late-onset sepsis episodes during the 4 weeks after enrollment, 33 of them were first episodes, including 8 culture-proven (24.2%), 14 probable (42.4%) and 11 possible (33.3%), based on study definitions. Six of the 33 episodes occurred before starting the treatment intervention. The overall sepsis rate was 17.4% (33/190), and 28.8% (23/80) among infants with a birth weight less than 1500g.

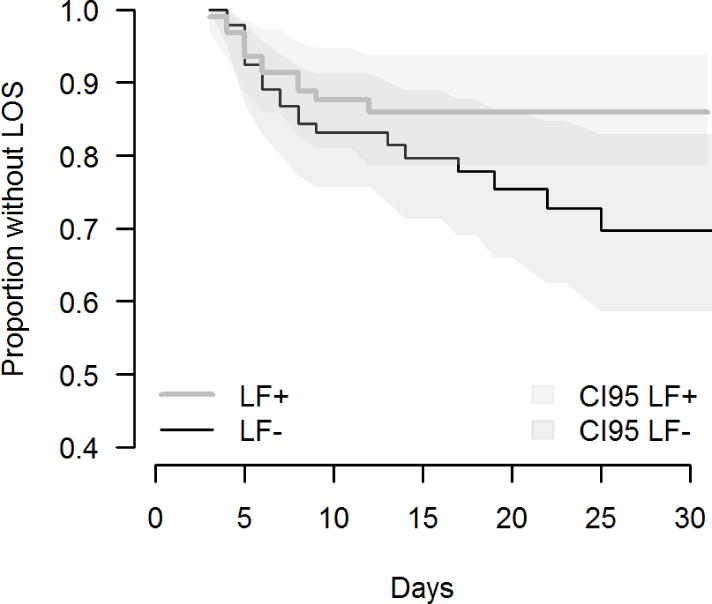

Sepsis occurred less frequently in the LF group than in the control group. In the intention-to-treat analysis, the cumulative sepsis incidence in the LF group was 12/95(12.6%) versus 21/95(22.1%) in the placebo group (Table 2). For the VLBW neonates (<1500g) the sepsis rates in the LF group was 8/40(20.0%) versus 15/40(37.5%) in the placebo group, a 46% reduction in sepsis. The crude risk ratio (RR) between groups was 0.57(95% CI: 0.30–1.09). The RR adjusted for birth weight category was 0.57(95% CI: 0.30–1.07) using GLM. Upon reviewing baseline and simple outcome tables, covariates were selected to be included in the adjusted analysis using Cox regression. The only significant term found in the Cox model was birth weight; the 95% confidence limits of the hazard ratio was 0.997–0.999, p<0.001. No statistically significant effect of lactoferrin upon hazard rate of first sepsis episode was detected. The hazard ratio of lactoferrin, after adjustment by birth weight, was 0.507 and the 95% confidence limits was between 0.249 and 1.034 (p=0.062). A non-adjusted Kaplan Meier plot illustrates constraints of the confidence limits (Figure 2). Of interest, after day 10 of intervention, there was 1 sepsis episodes in the LF group versus 6 in the placebo (Figure 2).

Table 2.

Sepsis outcomes

| Characteristics | Lactoferrin | Placebo | RR (95% CI) | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total late-onset sepsis episodes, n/total (%) | 12/95 (12.6%) | 21/95 (22.1%) | 0.57 (0.30 – 1.09) | 0.085 |

| Possible and probable late-onset sepsis | 8 | 17 | ||

| Confirmed late-onset sepsis | 4 | 4 | ||

| Late-onset sepsis by birth weight group, n/total (%) | 0.57 (0.30 – 1.07) | 0.047* | ||

| 501–1500g | 8/40 (20%) | 15/40 (37.5) | 0.53 (0.26 – 1.12) | |

| 15001–2500g | 4/55 (7.3%) | 6/55 (10.9%) | 0.67 (0.20 – 2.23) | |

| Age (days) at onset of first late-onset sepsis episode, mean (range) | 6.3 (3 – 12) | 9.5 (4 – 25) | 0.097 | |

| Mortality (prior to discharge), n/total (%) | ||||

| Overall (all causes) | 7/95 (7.4%) | 3/95 (3.1%) | 0.330 | |

| Sepsis-related | 4/95 (4.2%) | 2 /95 (2.1%) | 0.682 |

p value and confidence interval from GLM, adjusting for weight group

Figure 2.

Kaplan-Meier survival estimates: time to event of late-onset sepsis by treatment group. Blue line: lactoferrin; red line: placebo; blue shadow: lactoferrin 95% confidence interval; red shadow: placebo 95% confidence intervals. LOS: Late-onset sepsis

There were 4 episodes of culture proven sepsis in the LF group (Serratia sp, Enterobacter aerogenes, Klebsiella sp, and coagulase-negative Staphylococcus), vs 4 in the placebo group (Pseudomonas sp, Group B Streptococcus, Enterococcus faecalis, and coagulase-negative Staphylococcus). All pathogens were isolated from blood cultures, none from CSF. There were no significant differences with respect to other secondary outcomes.

Considering that children did not receive treatment until the start of oral or tube feeding (which was later for VLBW), we ran a secondary exploratory model using time since the start of the treatment. In this model, LF achieved significance (p=0.03); the 95% confidence limits for the hazard ratio of LF, after adjustment by birth weight, is between 0.0003 and 0.665.

There are no known risks related to LF intake13,14. Over 300 preterm newborns had taken bovine LF in a previous study with no LF related side effects11. However, since there was the remote possibility of an allergic reaction to cow milk proteins, we closely monitored for possible signs (allergic rhinitis, diarrhea, vomiting and eczema). There were no signs of allergy or treatment intolerance in 99.7% of observed days; there were only three episodes of vomiting during the intervention period. The overall medical and surgical complications/conditions during follow up where similar between groups, as well as growth measurements at 1 and 3 months of age (Table S2). Fourteen patients (7.4%) were re-hospitalized during the first three months of life, primarily for bronchiolitis (n=7), probable sepsis (n=3), pneumonia (n=2), anemia (n=1) and complication of an inguinal hernia (n=1). There were 11 deaths, two after the first month of life. The overall case-fatality rate was 5.8% (11/190); 38.9% (7/18) in the 500–1000g birth weight group. The DSMB had seven meetings to assess the safety of the intervention. None of the severe adverse events (14 re-hospitalizations and 11 deaths) were attributable to the intervention; all events were evaluated by the DSMB.

DISCUSSION

We were not able to demonstrate a statistically significant effect of LF on the rate of first late-onset sepsis episodes in infants with a birth weight < 2500g. However, the confidence limits for the hazard ratio of lactoferrin are suggestive of an effect that may be confirmed with a larger sample size. Although non-significant, there were less sepsis episodes in infants receiving LF, especially for VLBW neonates (46% reduction in sepsis). However, the study was not powered to detect significant difference in specific birth weight groups. Since many sepsis episodes occurred in the first week of life (Figure 2), and many of the infants had not received the intervention (LF or placebo) until the beginning of oral feeds, we have explored as a secondary analysis the effect of LF on sepsis using in the model time since the start of the treatment. Although in this model LF achieved significance, we do not consider it conclusive, since it was not the primary outcome in our trial design.

Our results are in concordance with Manzoni′s study11 and consistent with the potential for bovine LF to decrease infections in premature infants. The Italian study found a 66% reduction on sepsis episodes using LF in VLBW infants (RR 0.34, 95%CI: 0.17–0.70). However, there are some differences in study design that could explain some findings. First, we included infants with a birth weight up to 2500g; they included only infants <1500g. Second, we used a standardized dose by weight (200mg/kg/day); they used a fixed dose of 100mg/day for all infants. Third, we included as our main study outcome, not only culture-proven sepsis, but also clinical-defined sepsis (probable and possible). This study addressed some of the most important limitations in the Manzoni trial and presented important differences specific to resource-limited settings. Also, the LF we used was different from that used in Manzoni’s trial, the variation in the additives and purity of the LF could affect the results. In a follow up study Mazoni found a significant reduction in the incidence of NEC in VLBW neonates with LF supplementation15. In our study we were not able to evaluate the effect on NEC due to the small sample size.

Despite its preliminary nature and small sample size, our study included larger birth weight group infants to investigate the effect of LF on this population. The overall neonatal mortality rate is low for late preterm infants; however, infections among these infants increase the risk of complications, prolong hospital stay and increase mortality16. In developing countries, many neonatal deaths occur in non-low-birth weight infants2. Thus, we enrolled neonates up to 2500g. We included high-risk babies, typical of those admitted in most hospitals in Latin America. However, neonates with a birth weight >1500g have less risk of sepsis, and obviously impacted the overall sepsis rates in the study.

In the Italian study, as noted both by the authors themselves and subsequent editorial critiques17, the dose may have been inadequate for larger infants; no adjustments were made for birth weight. The protective effect of LF was clear for infants weighing <1000g, who received the higher dose per kilo. We standardize the dose by weight (200mg/kg/day), based on the dose effective in the smallest infants (500g) in Manzoni′s study. Other ongoing LF trials, like the ELFIN study in the UK (Enteral LactoFerrin In Neonates; https://www.npeu.ox.ac.uk/elfin) and the LIFT study in Australia (Lactoferrin Infant Feeding Trial; http://researchdata.ands.org.au/the-lactoferrin-infant-feeding-trial-lift) are also using a LF dose by weight (150mg/Kg/day).

This study has some limitations. First, the small sample size and power, due to the small number of high-risk VLBW infants. Second, the inclusion of culture-negative clinically-defined sepsis is not as precise as culture-proven infections as an outcome measurement. However, in developing countries, rates of clinically diagnosed neonatal sepsis are as high as 170/1000 live births whereas culture-confirmed sepsis are around 5.5/1000 live births due to limited laboratory capabilities2. Therefore, investigating the effect of LF on these clinically-defined sepsis episodes is of paramount importance in low and middle-income countries. For this trial we standardized sepsis definitions, using strict clinical and laboratory criteria, and evaluated each episode with an independent team of physicians. Third, we were not able to completely blind the study intervention. Both, LF and maltodextrin, were placed in capsules, which were then opened and diluted in breast milk or infant formula. However, the dilution of LF in milk still had a mild pink color. Thus, the nurses administering the intervention were not blinded; however, the physicians and the investigators that evaluated sepsis episodes as well as the statisticians remained blinded to treatment assignment throughout the study period. Fourth, in our study the treatment began when oral or tube feeding started. This is critically important and could explain the lack of significance. It is known from in vitro studies that LF (both bovine and human) is extremely active on the nascent enterocytes; it promotes cell proliferation in the first days of life18, 19. This is why many authors speculate that the anti-infectious role of LF relies strongly on its ability to interact with the immature enterocytes in the very first hours or days of life20. Nevertheless, despite these limitations, we suspect that the fundamental observation (LF decreases sepsis in neonates) is correct because it is consistent with experimental literature that has demonstrated LF’s protective effect against infections.

LF protects against pathogens in multiple ways: it sequesters iron essential for bacterial growth; binds to lipopolysaccharide on the cell surface of Gram negative bacteria, disrupting the bacterial cell membrane; it has anti-lipoteichoic acid (against Gram positive organisms) and anti-Candida cell wall activities; LF peptide fragments have in vitro bactericidal properties10. LF impairs the ability of pathogens to adhere/invade mammalian cells, by binding to, or degrading, specific virulence proteins21. In addition to the direct antimicrobial effect, LF protects against infection due to its immunomodulatory properties22, 23. This wide range of LF beneficial properties is related to its functional structure24.

In summary, this study shows feasibility of improving preterm infant health in developing countries by providing “added protection” with ingestion of a major milk protein. Within its preliminary nature, it has allowed more confident predictions of safety, cost, sepsis incidence in the target population, sample size power, and feasibility for extending it in resource-limited settings. Currently, we are conducting a larger trial on 414 neonates with a birth weight less than 2000g. In addition to confirming the suggested results of this preliminary study on sepsis prevention, we will follow infants up to 24 months of age to determine the effect of LF on growth and neurodevelopment (NICHD, R01-HD067694).

Given the high incidence and high morbidity and mortality of sepsis in preterm infants, efforts to reduce the rates of infection are among the most important interventions in neonatal care25. The use of LF as a broad-spectrum non-pathogen specific antimicrobial protective protein is an innovative approach that needs to be confirmed by multiple trials. If further studies confirm LF’s protective role, they will profoundly affect clinical care of neonates both in developed and developing countries, serving as a cost-effective strategy to decrease infections and its long-term consequences on growth and development.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

NEOLACTO Research Group: In addition to the bylined authors the research group also includes: Ana Lino MD (NICU, Hospital Nacional Alberto Sabogal Sologuren), Augusto Cama MD (NICU, Hospital Nacional Alberto Sabogal Sologuren), Anne Castañeda MD (NICU, Hospital Nacional Guillermo Almenara Irigoyen), Oscar Chumbes MD (NICU, Hospital Nacional Guillermo Almenara Irigoyen), Maria Luz Rospigliosi MD (NICU, Hospital Nacional Cayetano Heredia), Geraldine Borda MD (NICU, Hospital Nacional Cayetano Heredia), Margarita Llontop MD (NICU, Hospital Nacional Cayetano Heredia), and Thomas G. Cleary MD (Center for Infectious Diseases, University of Texas School of Public Health).

This work was funded by the Grand Challenges Explorations Grant from Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, Grant OPP1015669 (T.J.O.) and by the Public Health Service award R01-HD067694-01A1 from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD), USA (T.J.O.). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NICHD or the Gates Foundation.

We would like to thank all members of the participating Neonatal Units for their support and collaboration in the study. We also thank the study Research Nurses Cristina Suarez, Rocio Lucas and Lourdes Tucto; and the Neonatal Unit nurses Ivone Jara, Amelia Bautista, Ana Ulloa, Brígida Mejía, Iris Jara, Marlene Caffo, Rosa Atencio, Tania Quintana, Dina Irazabal, Amalia Escalante, Elizabeth Rojas, Iris Huamaní, Luisa Osorio, María Marres, Martha Torres, Rosa Quijano, Virginia Loo, Nelly Valverde, Clarisa Diaz, Giovana García and Nancy Cabrera for their dedication and careful work in this project. We also thank the members of the DSMB for their independent and critical review of the data and safety of the study.

Footnotes

Clinical Trial registry name: Pilot Study: Lactoferrin for Prevention of Neonatal Sepsis (NEOLACTO), identifier: NCT01264536.

Conflict of Interest: The authors have no conflicts of interests to disclose, and declare that the study sponsors (Gates Foundation and NICHD) had no role in the study design; the collection, analysis, and interpretation of data; the writing of the report; or the decision to submit the manuscript for publication. Dr. Theresa J. Ochoa, corresponding author, wrote the first draft of the manuscript, and did not receive any form of payment for its production.

References

- 1.Lawn JE, Rudan I, Rubens C. Four million newborn deaths: is the global research agenda evidence-based? Early Hum Dev. 2008;84(12):809–814. doi: 10.1016/j.earlhumdev.2008.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Thaver D, Zaidi AK. Burden of neonatal infections in developing countries: a review of evidence from community-based studies. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2009;28(1 Suppl):S3–9. doi: 10.1097/INF.0b013e3181958755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jones G, Steketee RW, Black RE, Bhutta ZA, Morris SS. How many child deaths can we prevent this year? Lancet. 2003;362(9377):65–71. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)13811-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lucas A, Morley R, Cole TJ, Gore SM. A randomised multicentre study of human milk versus formula and later development in preterm infants. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 1994;70(2):F141–146. doi: 10.1136/fn.70.2.f141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lucas A, Morley R, Cole TJ. Randomised trial of early diet in preterm babies and later intelligence quotient. BMJ. 1998;317(7171):1481–1487. doi: 10.1136/bmj.317.7171.1481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vohr BR, Poindexter BB, Dusick AM, et al. Beneficial effects of breast milk in the neonatal intensive care unit on the developmental outcome of extremely low birth weight infants at 18 months of age. Pediatrics. 2006;118(1):e115–123. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-2382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Howie PW, Forsyth JS, Ogston SA, Clark A, Florey CD. Protective effect of breast feeding against infection. BMJ. 1990;300(3716):11–16. doi: 10.1136/bmj.300.6716.11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Walker A. Breast milk as the gold standard for protective nutrients. J Pediatr. 2010;156(2 Suppl):S3–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2009.11.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ballard O, Morrow AL. Human Milk Composition: nutrients and bioactive factors. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2013;60(1):49–74. doi: 10.1016/j.pcl.2012.10.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brock JH. Lactoferrin–50 years on. Biochem Cell Biol. 2012;90(3):245–51. doi: 10.1139/o2012-018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Manzoni P, Rinaldi M, Cattani S, et al. Bovine lactoferrin supplementation for prevention of late-onset sepsis in very low-birth-weight neonates: a randomized trial. JAMA. 2009;302(13):1421–1428. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.1403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Haque KN. Definitions of bloodstream infection in the newborn. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2005;6(3 Suppl):S45–9. doi: 10.1097/01.PCC.0000161946.73305.0A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ochoa TJ, Chea-Woo E, Baiocchi N, et al. Randomized double-blind controlled trial of bovine lactoferrin for prevention of diarrhea in children. J Pediatr. 2013;162(2):349–56. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2012.07.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ochoa TJ, Pezo A, Cruz K, Chea-Woo E, Cleary TG. Clinical studies of lactoferrin in children. Biochem Cell Biol. 2012;90(3):457–67. doi: 10.1139/o11-087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Manzoni P, Meyer M, Stolfi I, et al. Bovine lactoferrin supplementation for prevention of necrotizing enterocolitis in very-low-birth-weight neonates: a randomized clinical trial. Early Hum Dev. 2014;90(Suppl 1):S60–5. doi: 10.1016/S0378-3782(14)70020-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Benjamin DK, Jr, Stoll BJ. Infection in late preterm infants. Clin Perinatol. 2006;33(4):871–882. doi: 10.1016/j.clp.2006.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kaufman DA. Lactoferrin Supplementation to Prevent Nosocomial Infections in Preterm Infants. JAMA. 2009;302(13):1467–1468. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.1449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Buccigrossi V, de Marco G, Bruzzese E, et al. Lactoferrin induces concentration-dependent functional modulation of intestinal proliferation and differentiation. Pediatr Res. 2007;61(4):410–4. doi: 10.1203/pdr.0b013e3180332c8d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lönnerdal B, Jiang R, Du X. Bovine lactoferrin can be taken up by the human intestinal lactoferrin receptor and exert bioactivities. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2011;53(6):606–14. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0b013e318230a419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Manzoni P, Mostert M, Stronati M. Lactoferrin for prevention of neonatal infections. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2011;24(3):177–82. doi: 10.1097/QCO.0b013e32834592e6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ochoa TJ, Cleary TG. Effect of lactoferrin on enteric pathogens. Biochimie. 2009;91(1):30–4. doi: 10.1016/j.biochi.2008.04.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vogel HJ. Lactoferrin, a bird’s eye view. Biochem Cell Biol. 2012;90(3):233–44. doi: 10.1139/o2012-016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Berlutti F, Schippa S, Morea C, et al. Lactoferrin downregulates pro-inflammatory cytokines upexpressed in intestinal epithelial cells infected with invasive or noninvasive Escherichia coli strains. Biochem Cell Biol. 2006;84(3):351–357. doi: 10.1139/o06-039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Baker HM, Baker EN. A structural perspective of lactoferrin function. Biochem Cell Biol. 2012;90(3):320–8. doi: 10.1139/o11-071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shane AL, Stoll BJ. Neonatal sepsis: progress towards improved outcomes. J Infect. 2014;68(Suppl 1):S24–32. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2013.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.