Abstract

While we have understood the basic outline of the enzymes and reactions that make up the traditional blood coagulation cascade for many years, recently our appreciation of the complexity of these interactions has greatly increased. This has resulted in unofficial “revisions” of the coagulation cascade to include new amplification pathways and connections between the standard coagulation cascade enzymes, as well as the identification of extensive connections between the immune system and the coagulation cascade. The discovery that polyphosphate is stored in platelet dense granules and is secreted during platelet activation has resulted in a recent burst of interest in the role of this ancient molecule in human biology. Here we review the increasingly complex role of platelet polyphosphate in hemostasis, thrombosis, and inflammation that has been uncovered in recent years, as well as novel therapeutics centered on modulating polyphosphate’s roles in coagulation and inflammation.

Keywords: Polyphosphate, Platelets, Coagulation, Thrombosis, Hemostasis

INTRODUCTION

Polyphosphate (polyP) is a highly anionic, linear strand of inorganic orthophosphate residues connected by high energy phosphoanhydride bonds (Fig. 1). It is found in all living organisms [1]. The most extensive research concerning polyP has occurred in bacteria and unicellular eukaryotes, where it is synthesized from ATP in a reversible, enzyme-catalyzed reaction in which the γ-phosphate of ATP is transferred to the end of the growing polyP chain [2]. PolyP is degraded by both nonspecific phosphatases such as alkaline phosphatase, as well as by specific endopolyphosphatases (which cleave internal phosphoanhydride bonds in polyP) and exopolyphosphatases (which release phosphate units from the termini of polyP) [1,2]. PolyP is thought to play many diverse roles in microorganisms, including an energy storage reservoir [3], a source of protection from heavy metal toxicity [4], and most recently, a molecular chaperone [5]. In addition, polyP is essential for the pathogenicity of many bacteria, again through a diverse array of mechanisms [6]. The discovery that platelet dense granules contain polyP and secrete it upon activation [7], coupled with the fact that patients with abnormal dense granule formation have lower levels of platelet polyP and exhibit bleeding diatheses [8], opened the door to investigations of the role of this ancient molecule in human physiology and disease. Although the pathways of polyP metabolism in mammalian cells are currently unknown, recent studies from our lab and others have shown that platelet polyP has prohemostatic, prothrombotic, and proinflammatory actions [9], making it an increasingly important player in our understanding of the interplay between blood clotting and innate immunity.

Figure 1.

PolyP is a linear polymer of inorganic phosphates held together by the same type of high-energy phosphoanhydride bonds found in ATP.

NEW CONNECTIONS IN COAGULATION AND INFLAMMATION

PolyP introduces new connections in the classical coagulation cascade

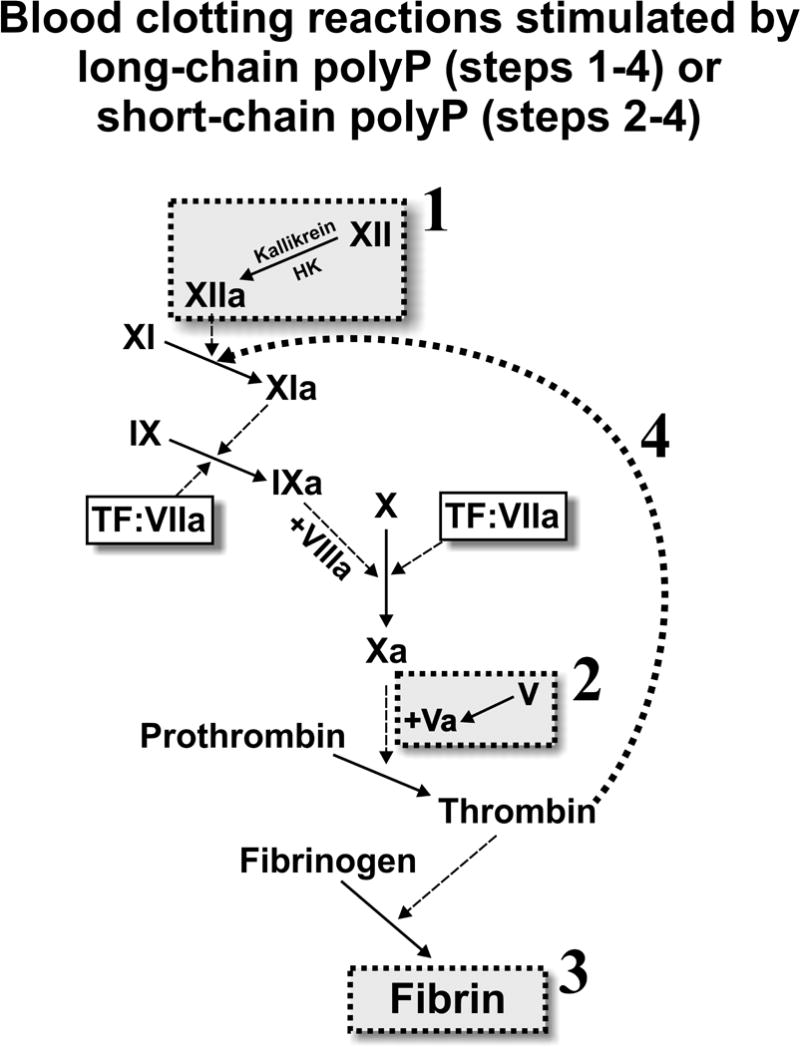

The standard coagulation cascade model allows for a relatively useful and straightforward understanding of the protein interactions and enzymatic reactions that lead to blood coagulation in vitro and in vivo. Even in some of its earliest iterations it contained mysteries however, such as the contact system, which was seemingly activated by only non-physiologic substances such as glass, kaolin, or diatomaceous earth, that do not play a role in hemostasis in humans [10]. Recent studies suggest that the contact system is more relevant than previously thought—especially in regards to its role in thrombosis [11], and many novel players, such as polyP, are challenging our understanding of the classic coagulation cascade (reviewed by [9]). Fig. 2 summarizes the points in the clotting cascade at which polyP has been found to act.

Figure 2.

PolyP modulates the blood clotting cascade by: (1) potently triggering the contact pathway of blood clotting; (2) accelerating factor V activation; (3) enhancing fibrin clot structure; and (4) greatly accelerating the rate of factor XI activation by thrombin. Reaction 1 requires long-chain polyP of the type present in microbes (hundreds of phosphates long). The other three reactions are promoted by both long-chain polyP and polyP of the size secreted by platelets (about 60–100 phosphates long), although enhancement of fibrin clot structure is most significant in the presence of long-chain polyP.

One of the most important aspects of polyP’s ability to modulate blood coagulation and inflammation is its ability to bind to certain coagulation enzymes, including kallikrein, thrombin, and factor XIa [12]. In addition, polyP can bind to various proteins found within platelet releasate, many of which are important for platelet function in coagulation and inflammation (unpublished data).

This ability of polyP to bind to multiple coagulation enzymes makes it likely that polyP serves as a template to bring blood clotting proteins together, thereby increasing the likelihood that the proteins will encounter each other within the complex environment of in vivo blood clot formation. PolyP may also serve as an allosteric activator of certain blood clotting enzymes, such as factor XII [13]. In particular, polyP has been shown to enhance the autoactivation of factor XII, to accelerate the activation of factor V by both thrombin and factor XIa, and to greatly accelerate the activation of factor XI by thrombin [9]. This last function—the ability of platelet polyP to accelerate factor XI activation by thrombin—may explain the otherwise very puzzling role of factor XI in normal hemostasis. In addition, polyP has been shown to bind to fibrin(ogen) and to enhance the structure and stability of fibrin clots, rendering them stronger and more resistant to fibrinolysis (reviewed in [9]).

One intriguing finding concerning polyP’s role in coagulation is that platelet-derived polyP is on average 60–100 phosphates in length, while microbial derived polyP is much more heterodisperse, and can be up to thousands of phosphates long [14]. This distinction appears to be important in discerning the role of polyP in biology, since polyP chains of varying lengths have differing effects on coagulation and inflammation [14]. While platelet polyP is the ideal size for enhancing the amplification steps of the coagulation cascade and acting as a physiological mediator of factor XI function, longer polyP chains are needed for triggering blood clotting via factor XII, and for enhancement of fibrin clot structure (Fig. 2).

PolyP as a mediator between coagulation and inflammation

Hematology researchers and physicians have a rapidly growing appreciation for the interconnectedness of coagulation and inflammation [15], and much of it is centered on platelets as novel immune mediator cells [16]. Interestingly, our understanding of the increasing connection between inflammation and coagulation has been accompanied by another increasing appreciation for the differences between the processes of normal hemostasis and pathological thrombosis [17]. PolyP’s dual role in both coagulation and inflammation has made it a model molecule for studying these complex interactions between coagulation, inflammation, and thrombosis.

PolyP has been shown to activate NF-κB in endothelial cells, inducing apoptosis, leukocyte extravasation, and increased vascular permeability [18]. PolyP bound to histones has also been shown to enhance platelet activation and thrombin generation through toll-like receptor 2 and 4 signaling [19]. PolyP’s ability to amplify the rate of coagulation reactions and link them to increased inflammation and vascular leakage may have implications in disorders such as sepsis, where widespread inflammation, platelet activation, and coagulation dysregulation cause extremely high rates of organ failure and death. In fact, one of the most recent candidates for treatment of sepsis-related disorders, activated protein C [20], has been shown to counteract many of polyP’s proinflammatory and prothrombotic effects [18]. This suggests that targeting polyP might have important benefits in disorders of combined coagulation and inflammation.

NEW DIAGNOSTICS AND THERAPEUTICS

Developing polyP diagnostics

One of the main challenges of working with polyP is that its ubiquity and simple structure leave it intractable to many of the standard biochemical assays. While there are numerous (often debated) methods for quantifying polyP from biological samples [21] or staining polyP for fluorescent microscopy [22], these techniques are often most suited to single cell types with relatively high concentrations of polyP. Adapting these techniques to human tissues is a complex and laborious process, but it promises intriguing insight in polyP’s effects on human biology in vivo. One of the first examples of this would be an in-depth investigation of the polyP levels of localization in various human tissues. There are some reports of the quantification of polyP in various mammalian tissues [23], but our increased understanding of the importance of polyP in mammalian biology calls for a more updated and comprehensive analysis. A measure of polyP levels and localization in normal human tissues would also give us a starting point for examining the role of polyP in prothrombotic or proinflammatory disease states. For example, it is possible that various disease states (in addition to the aforementioned dense-granule storage disorders) could be accompanied by changes in polyP concentration, chain length, or storage. Diagnostics that could quantify polyP in human samples might provide additional information about the disease state of a particular patient.

Novel therapeutics targeting polyP

Polycationic compounds have been shown to be effective in inhibiting the interaction between polyP and coagulation enzymes in vitro, and in mouse models they have shown efficacy as antithrombotics with reduced bleeding side effects compared to heparin [24]. Inhibition of polyP-mediated amplification of coagulation might therefore be a therapeutic target for interrupting thrombosis without the bleeding risk that comes from conventional anticoagulant drugs that inhibit essential enzymes of the classical coagulation cascade.

Hemostatic therapeutics utilizing polyP

Current hemostatic agents, especially those designed to treat internal bleeding, are based upon recombinant proteins that are expensive to produce on a large scale and have relatively short shelf lives once reconstituted. PolyP, on the other hand, is already made in industrial quantities cheaply, and is very stable under appropriate storage conditions. PolyP-based hemostatic agents are therefore an intriguing possibility for treating bleeding disorders. Recently, silica nanoparticles functionalized with polyP have been shown to be more effective than polyP alone in enhancing coagulation [25], providing proof of principle for polyP based hemostatic agents in the future.

CONCLUSIONS

The discovery of polyP in platelets and its multi-faceted role in coagulation and inflammation contributes to our evolving understanding of the complex role of coagulation enzymes, both within and outside of the mechanisms of normal hemostasis. These discoveries open the door to research into future diagnostics that enhance our understanding of polyP’s role in human biology. PolyP is also both a potential drug target and potential therapeutic agent, for treating deadly disorders of bleeding, coagulation, and inflammation.

Acknowledgments

The authors’ studies were supported in part by grant R01 HL047014 from the National Heart Lung and Blood institute of the NIH.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest disclosure

The authors are co-inventors on patent applications on medical uses of polyphosphate and inhibitors of polyphosphate.

References

- 1.Docampo R, Ulrich P, Moreno SN. Evolution of acidocalcisomes and their role in polyphosphate storage and osmoregulation in eukaryotic microbes. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2010;365(1541):775–84. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2009.0179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kornberg A, Rao NN, Ault-Riche D. Inorganic polyphosphate: a molecule of many functions. Annu Rev Biochem. 1999;68:89–125. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.68.1.89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rao NN, Gomez-Garcia MR, Kornberg A. Inorganic Polyphosphate: Essential for Growth and Survival. Ann Rev Biochem. 2009;78:605–47. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.77.083007.093039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Keasling JD. Regulation of intracellular toxic metals and other cations by hydrolysis of polyphosphate. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1997;829:242–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1997.tb48579.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gray MJ, Wholey WY, Wagner NO, Cremers CM, Mueller-Schickert A, Hock NT, et al. Polyphosphate is a primordial chaperone. Mol Cell. 2014;53(5):689–99. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2014.01.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shi X, Rao NN, Kornberg A. Inorganic polyphosphate in Bacillus cereus: motility, biofilm formation, and sporulation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101(49):17061–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0407787101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ruiz FA, Lea CR, Oldfield E, Docampo R. Human platelet dense granules contain polyphosphate and are similar to acidocalcisomes of bacteria and unicellular eukaryotes. J Biol Chem. 2004;279(43):44250–7. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M406261200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hernandez-Ruiz L, Saez-Benito A, Pujol-Moix N, Rodriguez-Martorell J, Ruiz FA. Platelet inorganic polyphosphate decreases in patients with delta storage pool disease. J Thromb Haemost. 2009;7(2):361–3. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2008.03238.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Smith SA, Morrissey JH. Polyphosphate: a new player in the field of hemostasis. Curr Opin Hematol. 2014;21(5):388–94. doi: 10.1097/MOH.0000000000000069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Colman RW, Schmaier AH. Contact system: a vascular biology modulator with anticoagulant, profibrinolytic, antiadhesive, and proinflammatory attributes. Blood. 1997;90(10):3819–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Blat Y, Seiffert D. A renaissance for the contact system in blood coagulation? Thromb Haemost. 2008;99(3):457–60. doi: 10.1160/TH07-11-0692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Choi SH, Collins JN, Smith SA, Davis-Harrison RL, Rienstra CM, Morrissey JH. Phosphoramidate end labeling of inorganic polyphosphates: facile manipulation of polyphosphate for investigating and modulating its biological activities. Biochemistry. 2010;49(45):9935–41. doi: 10.1021/bi1014437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Engel R, Brain CM, Paget J, Lionikiene AS, Mutch NJ. Single-chain factor XII exhibits activity when complexed to polyphosphate. J Thromb Haemost. 2014;12(9):1513–22. doi: 10.1111/jth.12663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Smith SA, Choi SH, Davis-Harrison R, Huyck J, Boettcher J, Rienstra CM, et al. Polyphosphate exerts differential effects on blood clotting, depending on polymer size. Blood. 2010;116(20):4353–9. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-01-266791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dahlback B. Coagulation and inflammation–close allies in health and disease. Semin Immunopathol. 2012;34(1):1–3. doi: 10.1007/s00281-011-0298-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Elzey BD, Tian J, Jensen RJ, Swanson AK, Lees JR, Lentz SR, et al. Platelet-mediated modulation of adaptive immunity. A communication link between innate and adaptive immune compartments. Immunity. 2003;19(1):9–19. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(03)00177-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McFadyen JD, Jackson SP. Differentiating haemostasis from thrombosis for therapeutic benefit. Thromb Haemost. 2013;110(5):859–67. doi: 10.1160/TH13-05-0379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bae JS, Lee W, Rezaie AR. Polyphosphate elicits pro-inflammatory responses that are counteracted by activated protein C in both cellular and animal models. J Thromb Haemost. 2012;10(6):1145–51. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2012.04671.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Semeraro F, Ammollo CT, Morrissey JH, Dale GL, Friese P, Esmon NL, et al. Extracellular histones promote thrombin generation through platelet-dependent mechanisms: involvement of platelet TLR2 and TLR4. Blood. 2011;118(7):1952–61. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-03-343061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Marti-Carvajal AJ, Sola I, Gluud C, Lathyris D, Cardona AF. Human recombinant protein C for severe sepsis and septic shock in adult and paediatric patients. Cochrane Satabase Syst Rev. 2012(12):CD004388. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004388.pub6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Martin P, Van Mooy BA. Fluorometric quantification of polyphosphate in environmental plankton samples: extraction protocols, matrix effects, and nucleic acid interference. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2013;79(1):273–81. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02592-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gomes FM, Ramos IB, Wendt C, Girard-Dias W, De Souza W, Machado EA, et al. New insights into the in situ microscopic visualization and quantification of inorganic polyphosphate stores by 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI)-staining. Eur J Histochem. 2013;57(4):e34. doi: 10.4081/ejh.2013.e34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kumble KD, Kornberg A. Inorganic polyphosphate in mammalian cells and tissues. J Biol Chem. 1995;270(11):5818–22. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.11.5818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Travers RJ, Shenoi RA, Kalathottukaren MT, Kizhakkedathu JN, Morrissey JH. Nontoxic polyphosphate inhibitors reduce thrombosis while sparing hemostasis. Blood. 2014;124(22):3183–90. doi: 10.1182/blood-2014-05-577932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kudela D, Smith SA, May-Masnou A, Braun GB, Pallaoro A, Nguyen CK, et al. Clotting Activity of Polyphosphate-Functionalized Silica Nanoparticles. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2015 doi: 10.1002/anie.201409639. In Press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]