Abstract

In the US, African Americans and other minority groups have longer wait times to deceased donor kidney transplantation than Caucasians. To date, the role of geographic distribution of racial and ethnic groups as a determinant of wait times has not been fully elucidated. Using the Scientific Registry of Transplant Recipients database, all registrants for kidney transplant between 2004 and 2007 (n = 126 094) were analyzed from time of waitlisting until nonzero antigen mismatched deceased donor kidney transplant. Nationally, deceased donor transplantation occurred at a lower rate for African Americans (hazard ratio [HR] 0.85, confidence interval [CI] 0.83–0.87), Hispanics (HR 0.68, CI 0.66–0.70), Asians/Pacific Islanders (HR 0.77, CI 0.73–0.80) and Other minority groups (HR 0.74, CI 0.69–0.81) compared to Caucasians. Multivariate modeling for age, gender, cause of end-stage renal disease, ABO type, panel reactive antibody, HLA-DR frequency, expanded criteria donor status and prior kidney donation only partially accounted for this difference. Adjusting for these variables and organ procurement organization of listing, African Americans (HR 1.03, CI 1.00–1.06), Hispanics (HR 1.15, CI 1.10–1.19), Asians/Pacific Islanders (HR 1.36, CI 1.30–1.43) and Other minority groups (HR 1.00, CI 0.92–1.09) were transplanted at similar or higher rates than Caucasians. Our findings show that geographic location of waitlisted candidates is the most important contributor to racial disparities in waiting times for deceased donor kidney transplantation.

Introduction

Renal transplant is the optimal renal replacement therapy in end-stage renal disease (ESRD) and is associated with increased quality of life and reduced morbidity and mortality compared to dialysis. Access to transplant in the United States is not equal, however, with minority candidates experiencing median wait times nearly twice those of Caucasian candidates (1). Many reasons for this disparity have been posited including socioeconomic disadvantage, lower levels of education (2–5), differing personal and cultural beliefs (6), provider attitudes (7,8), variable geographic distribution of patients (9,10), decreased availability of living donors (11,12), higher prevalence of presensitization, unfavorable ABO blood types (13) and competition for uncommon HLA genotypes (14–19). A longitudinal study of 228 552 patients with ESRD from 1991 to 1997 by Wolfe et al demonstrated that even when adjusting for age, sex, race, cause of ESRD, region and date of waitlisting, racial disparities in access to deceased donor kidney transplantation persisted for African Americans (18). Another analysis by Hall et al of wait times to and relative rates of deceased donor kidney transplant in 503 090 incident ESRD patients between 1995 and 2006 revealed disparities not only for African Americans but also for Hispanics, Asians, American Indians/Alaska Natives and Pacific Islanders (13). To address this inequity, national kidney allocation policy was changed May 7, 2003, to remove points for HLA-B matching in organ allocation (20). Minority groups subsequently saw a rise in rates of transplantation to a degree greater than that seen in Caucasians, though overall transplantation rates for minorities continue to lag behind what is expected based on their proportionate representation on the waitlist (21). Despite efforts to minimize racial inequity in organ allocation, African Americans and other minority candidates in the United States continue to experience longer wait times than Caucasians. The role of geographic distribution of these different groups in the context of organization of organ procurement organization (OPO) boundaries has to date not been fully investigated.

In the 2010 US census, 97% of the population self-reported a single race. Caucasians represented the largest group with 72.4% of the total population, followed by African Americans (12.6%), Asians (4.8%), American Indians and Alaska Natives (0.9%) and Native Hawaiian and Other Pacific Islanders (0.2%). Of this population, 16.3% of respondents also identified themselves as Hispanic or Latino. Closer examination of census data shows that minority distribution across the United States is not uniform. The majority of those self-reporting as African American lived in the south (55%), while only 9.8% lived in the western United States (22). Geographic discrepancies in ethnic and racial distribution have major implications for the waitlisting and transplantation of minorities. Chronic kidney disease and ESRD are known to be more prevalent within African American and Hispanic populations, and regions with a higher prevalence of minorities have in general a higher incidence of ESRD. A study by Mathur et al (10) demonstrated that areas with larger proportions of high ESRD incidence racial groups (African Americans and Native Americans) had not only higher overall rates of ESRD but also lower transplant rates for all ESRD patients within these areas. Greater demand for transplant in the setting of limited organ supply ultimately produces longer wait times. Regional variability in distribution of ESRD incidence will inevitably affect access to transplant so long as organs are shared within arbitrarily drawn geographic boundaries (10).

Within this context we sought to examine the role of arbitrarily designated geographic boundaries assigned to OPOs—the organizations charged with allocating solid organs—in the persistence of racial disparities in renal transplantation. This difference in waiting time is only partially explained by age, race, sex, cause of ESRD, willingness to accept an expanded criteria donor (ECD) organ, presensitization, incidence of rare HLA genotypes and frequencies of ABO types in the minority population. We hypothesize that geographic location of a candidate and OPO of listing is one of the most important factors determining waiting time to deceased donor kidney transplant and that minorities are more likely to live in OPOs with longer waiting times.

Concise Methods

Data on all waitlisted candidates for deceased donor kidney transplantation in the Scientific Registry of Transplant Recipients (SRTR) database listed between January 1, 2004 and December 31, 2007 were included in the study cohort. This time period was selected to include the current United Network for Organ Sharing (UNOS) point system for allocation and to allow sufficient follow-up of candidate outcomes. Registrants were followed from time of listing until event of interest, censoring, or until the end of the data set on February 28, 2011. Censoring events included living donor kidney transplant, zero antigen mismatch deceased donor kidney transplant, removal from the waitlist, death on the waitlist and remaining on the waitlist at the end of the study period. Candidates listed for simultaneous kidney–pancreas transplants or other multi-organ transplants were excluded from the analysis. The cohort encompassed all ages including pediatric candidates.

Candidate race and/or ethnicity were determined from the candidate race variable in the SRTR database and were then grouped into five categories for the purposes of this study: Caucasian, African American, Hispanic, Asian/Pacific Islander and Other. The Hispanic category included those individuals self-identifying as Latino and those designated as both Caucasian and Hispanic. Any race/ethnicity variable listed as Unknown was included in the Other category in the analysis. The waiting list population data included the OPO servicing the center of listing. The median wait times for each OPO were used to rank the 58 OPOs from shortest to longest wait time and were then used to divide them into quartiles of waiting time. Two OPOs had average waiting times greater than 8.5 years and did not have sufficient follow-up time to determine the median waiting time, and were thus assigned to the longest waiting time quartile. The racial composition of each OPO was determined from the data.

Time on the waiting list was calculated from the date of listing regardless of status, either active or inactive, until the day of deceased donor kidney transplant, living donor kidney transplant, death, delisting or the end date of data collection. For the time to event analysis, the event was defined as a nonzero HLA mismatched deceased donor kidney transplant. Since zero HLA mismatched kidneys are shared among all OPOs, they were censored at the time of transplant. Candidates who received living donor transplants were censored at the time of transplant. Besides administrative censoring at the end date of the study period, candidates who died on the waiting list were also censored at the time of death. For candidates listed for transplant within multiple OPOs, only the OPO in which they received their nonzero antigen mismatched kidney transplant was credited for an event. In the other OPOs, the candidate was censored at the time of transplant. Kaplan–Meier survival plots were used to determine the median waiting time to nonzero HLA mismatched deceased donor kidney transplant by race and ethnicity. Log-rank testing was used to determine the statistical significance.

Cox proportional hazards models were used to determine the independent effect of the covariates of interest. The covariates included in the model were age, gender, race/ethnicity, history of previous kidney donation, ABO blood type, panel reactive antibody (PRA), HLA-DR genotype frequency, cause of ESRD (diabetes mellitus, hypertension, glomerulonephritis, polycystic kidney disease and other/unknown), willingness to accept an ECD organ and OPO of listing. ECD kidneys are allocated only on the amount of wait time the candidate has accrued on the list; factors such as HLA-DR matching and PRA are not included in the matching algorithm for these organs. The HLA-DR genotype frequency was determined from all kidney alone waiting list candidates listed from 1988 to present. The frequency was then determined by dividing the number of unique HLA-DR allele pairs by the total number of registrants in the waitlisted population. Due to the concern of a clustering effect of OPO, a Cox regression where OPO was considered as a random effect was also performed. To validate that the effect of geographic location of waitlisted candidates on racial disparities was robust with respect to the defining event and censoring strategy in the Cox model, we performed four additional competing risk regression analyses using the Fine and Gray method (23). In the competing risk analyses, the primary event was nonzero HLA mismatched deceased donor kidney transplant or any deceased donor kidney transplants, while death and living donor transplantation were considered as competing events. The analyses were adjusted for the same covariates as in the Cox regression and then repeated for only adult registrants. All statistical analysis except the competing risk regression was performed using SPSS version 19.0 (IBM, Armonk, NY). The competing risk regression was performed using the cmprsk package in R software version 2.15.0 (http://www.r-project.org).

Results

There were 126 094 new deceased donor kidney transplant listings identified between January 1, 2004 and December 31, 2007. Candidates listed for simultaneous kidney–pancreas transplant or other multi-organ transplants were excluded from the analysis. All events excepting nonzero antigen mismatched deceased donor renal transplant were censored. Table 1 shows the characteristics of the listed populations by race/ethnicity. Table 2 shows the distribution of potential outcomes of transplant listing by race and ethnicity over the study period. With the exception of Asians and Pacific Islanders, minority candidates were on average slightly younger than Caucasians. There was a male predominance for all the racial/ethnic groups, with Caucasian candidates having the highest prevalence of male registrants. ABO blood type varied significantly by race/ethnicity. Notably, Caucasians had a higher prevalence of blood type A than all other racial/ethnic groups. In contrast, blood type B was most common among African Americans and Asians/Pacific Islanders. Blood type O was most common among Hispanics and least common among Asians and Pacific Islanders. The cause of ESRD varied considerably based on race/ethnicity. Diabetes mellitus was the most common cause in the Hispanic population, while hypertension was the most common cause in the African American cohort. The percentage of candidates with PRA greater than 79% was small for all groups but highest for African Americans. The median DR genotype frequency also varied considerably by race/ethnicity, with Caucasians having genotypes seen more frequently in the donor pool and Asians and Pacific Islanders having genotypes occurring less frequently in the donor pool. Very few candidates in any of the racial/ethnic groups had been previous organ donors. African Americans were more likely than other racial/ethnic groups to be listed for ECD organs.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of waitlisted candidates for deceased donor kidney transplant by race/ethnicity for registrants to the SRTR between January 1, 2004 and December 31, 2007

| Caucasian (n = 62 084) | African American (n = 34 984) | Hispanic (n = 19 285) | Asian/Pacific Islander (n = 7435) | Other (n = 2306) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All registrants (%)1 | 49.2 | 27.7 | 15.3 | 5.9 | 1.8 |

| Recipient age (mean, std)1 | 50.8 ± 14.6 | 47.7 ± 13.7 | 46.6 ± 15.4 | 50.4 ± 14.0 | 48.5 ± 14.6 |

| Male sex (%)1 | 61.5 | 57.6 | 60.6 | 56.3 | 56.0 |

| ABO type (%)1 | |||||

| A | 40.4 | 25.8 | 28.8 | 25.2 | 29.7 |

| AB | 3.9 | 4.3 | 2.2 | 7.3 | 2.6 |

| B | 10.8 | 19.8 | 9.9 | 28.3 | 13.9 |

| O | 45.0 | 50.1 | 59.1 | 39.3 | 53.8 |

| Etiology of end-stage renal disease (%) | |||||

| Diabetes mellitus | 24.9 | 25.9 | 38.3 | 30.9 | 46.8 |

| Glomerulonephritis | 13.2 | 10.4 | 9.2 | 17.0 | 11.9 |

| Hypertension | 14.0 | 37.3 | 19.3 | 20.6 | 14.0 |

| Polycystic kidney disease | 11.9 | 2.9 | 4.5 | 3.8 | 3.6 |

| Other or unspecified | 36.1 | 23.5 | 28.7 | 27.7 | 23.8 |

| OPO by quartile of wait time (%)1 | |||||

| 1 (shortest) (n = 14 889) | 66.9 | 23.1 | 5.5 | 2.8 | 1.6 |

| 2 (n = 22 501) | 51.3 | 28.1 | 15.6 | 3.8 | 1.2 |

| 3 (n = 30 453) | 54.2 | 30.8 | 9.6 | 3.3 | 2.1 |

| 4 (longest) (n = 58 251) | 41.3 | 27.2 | 20.7 | 8.8 | 2.0 |

| PRA >79% (%)2 | 5.2 | 7.5 | 5.4 | 3.9 | 6.0 |

| DR genotype frequency (median)1 | 0.01553 | 0.01310 | 0.01457 | 0.00677 | 0.00972 |

| Percent of candidates having previously donated a kidney (%) | 0.06 | 0.10 | 0.04 | 0.05 | 0.09 |

| Inactive at time of waitlisting (%)3 | 17.7 | 19.5 | 19.6 | 16.0 | 14.9 |

| Listed for ECD organ at time of waitlisting (%) | 41.9 | 46.0 | 42.1 | 37.5 | 39.6 |

| Multiple listings (%) | 8.7 | 7.4 | 7.6 | 10.5 | 9.8 |

ECD, expanded criteria donor; OPO, organ procurement organization; PRA, panel reactive antibody; SRTR, Scientific Registry of Transplant Recipients; std, standard deviation.

No missing data.

Missing data 10.0%, n = 12 602.

Initial status at time of waitlisting was missing for 5.7% of registrants and these registrants were assumed to be active at the time of waitlisting for the purpose of our analysis.

Table 2.

Distribution of outcomes of listing for deceased donor kidney transplant by race/ethnicity for registrants to the SRTR between January 1, 2004 and December 31, 2007 followed until the end of the study period on February 28, 20111

| Caucasian (n = 62 084) | African American (n = 34 984) | Hispanic (n = 19 285) | Asian/Pacific Islander (n = 7435) | Other (n = 2306) | Total (n = 126 094) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nonzero antigen mismatched deceased donor kidney transplant (%) | 23.5 | 31.4 | 23.8 | 27.9 | 25.9 | 26.0 |

| Zero antigen mismatch deceased donor kidney transplant (%) | 6.0 | 1.7 | 4.4 | 1.4 | 3.3 | 4.2 |

| Living donor kidney transplant (%) | 28.1 | 10.7 | 17.3 | 13.5 | 16.4 | 20.5 |

| Died on list (%) | 12.0 | 13.9 | 12.1 | 11.3 | 13.7 | 12.6 |

| Delisted (%) | 9.1 | 12.3 | 12.1 | 12.3 | 14.5 | 10.7 |

| Remaining on list (%) | 21.3 | 30.1 | 30.2 | 33.6 | 26.2 | 25.9 |

| Median follow-up time (years) | 1.20 | 2.47 | 2.19 | 2.35 | 2.22 | 1.74 |

SRTR, Scientific Registry of Transplant Recipients.

No missing data.

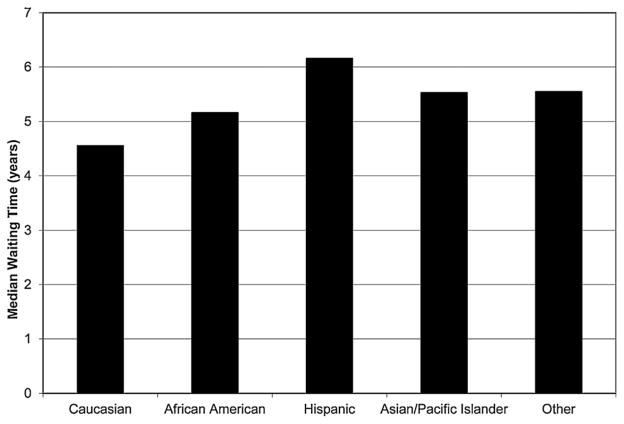

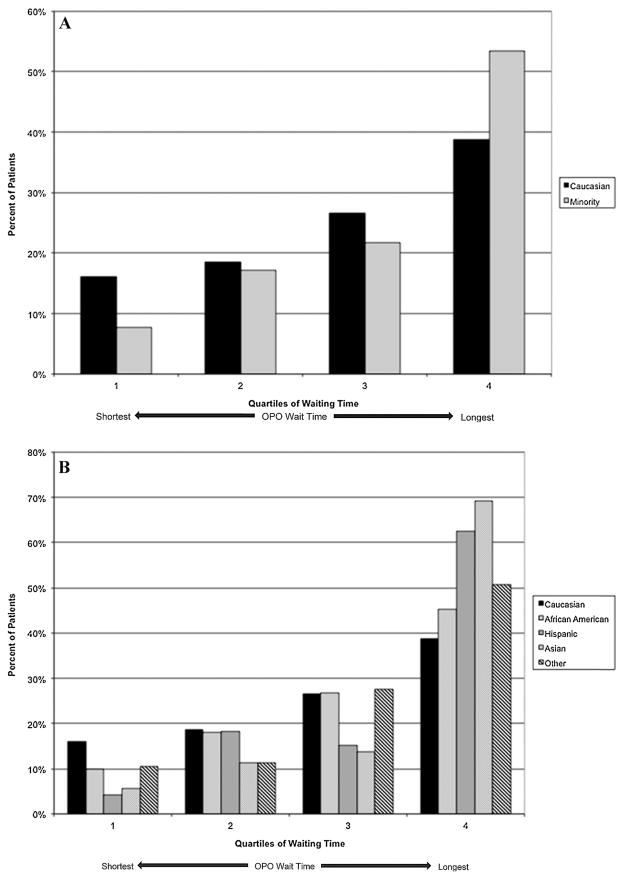

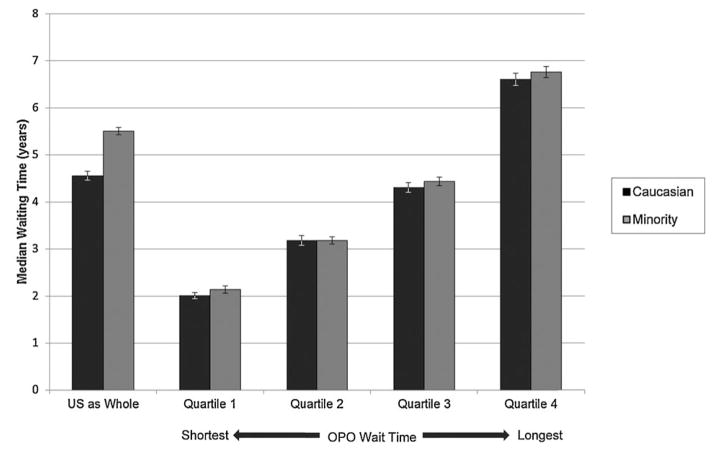

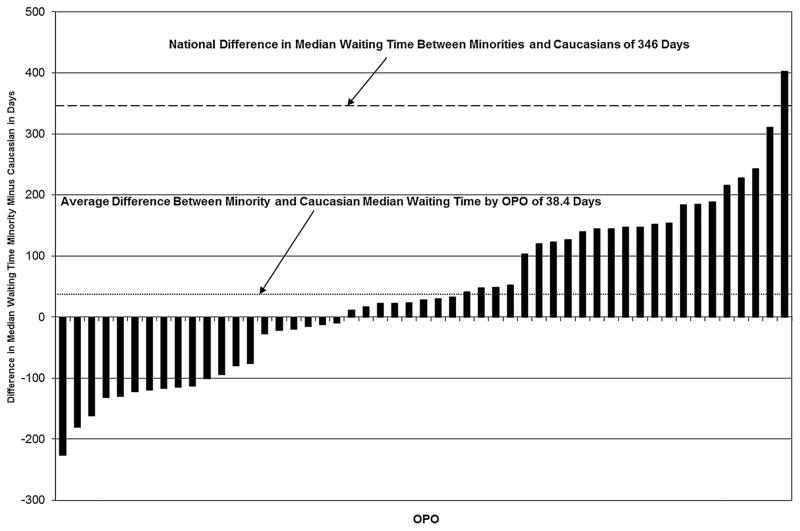

Figure 1 shows the median waiting times by race/ethnicity for the patients receiving a nonzero antigen mismatch deceased donor kidney transplant. On a national level, the unadjusted hazard ratio (HR) of nonzero antigen mismatch deceased donor transplantation was lower for African Americans (HR 0.85, confidence interval [CI] 0.83–0.87), Hispanics (HR 0.68, CI 0.66–0.70), Asians and Pacific Islanders (HR 0.77, CI 0.73–0.80) and Other minority groups (HR 0.74, CI 0.69–0.81) than Caucasians (Table 3). Figure 2A shows the distribution of minorities and Caucasians by OPO of listing broken into quartiles of median waiting time. Minority candidates were less commonly listed in OPOs with shorter waiting times and more likely to be listed in OPOs with longer waiting times. Figure 2B shows the same data but broken down by minority type. Hispanic and Asian/Pacific Islander candidates had the greatest maldistribution based on waiting times while African American and other minority distributions were closer to that found in Caucasians. Figure 3 shows the median waiting time for Caucasians and minorities in the United States as a whole and for each of the quartiles of median waiting time, with quartile 1 including OPOs with the shortest wait times and quartile 4 including OPOs with the longest wait times. Figure 4 shows the difference in median wait time between minority and Caucasian candidates on the waiting list by OPO, with each of the 51 bars representing an individual OPO. Seven of the 58 existing OPOs were excluded from this graph, with one OPO without enough Caucasian candidates; two due to median wait times for both minorities and Caucasians not reached in the follow-up time; two due to median wait times for minorities not reached in the follow-up time and two due to median wait times in Caucasians not reached in the follow-up time. The average difference in wait time between minority and Caucasian candidates in the remaining OPOs was a mere 38.4 days compared to a national difference in wait time of 346 days for all candidates on the waiting list. Much of the difference is attributable to disproportionate effects of larger OPOs on national wait times and by the inability to include seven OPOs with the longest, and thus incalculable, median wait times in the analysis. At an OPO level, racial disparities are not as apparent and, indeed, 14 OPOs had significantly shorter wait times for minorities compared to Caucasians.

Figure 1. National median waiting time for nonzero antigen mismatched deceased donor kidney transplant by race/ethnicity for registrants to the Scientific Registry of Transplant Recipients between January 1, 2004 and December 31, 2007.

Log-rank p-value <0.0001.

Table 3.

Cox proportional hazards model of time to nonzero antigen mismatch deceased donor kidney transplantation for registrants to the SRTR between January 1, 2004 and December 31, 2007

| Caucasian (reference group) | African American | Hispanic | Asian/Pacific Islander | Other | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All listings | |||||

| Unadjusted HR of nonzero antigen mismatch deceased donor kidney transplantation (95% CI) | 1 | 0.85 (0.83–0.87) | 0.68 (0.66–0.70) | 0.77 (0.73–0.80) | 0.74 (0.69–0.81) |

| Adjusted HR for PRA, ABO type, age, previous organ donation, DR genotype frequency, willingness to accept an ECD organ, gender, and cause of kidney disease (95% CI)) | 1 | 0.94 (0.91–0.97) | 0.73 (0.70–0.75) | 0.85 (0.81–0.89) | 0.85 (0.79–0.93) |

| Adjusted HR for above plus OPO of listing (95% CI | 1 | 1.03 (1.00–1.06) | 1.15 (1.10–1.19) | 1.36 (1.30–1.43) | 1.00 (0.92–1.09) |

| Initial active listings only | |||||

| Unadjusted HR of nonzero antigen mismatch deceased donor kidney transplantation (95% CI) | 1 | 0.85 (0.83–0.87) | 0.70 (0.68–0.73) | 0.75 (0.71–0.79) | 0.72 (0.66–0.78) |

| Adjusted HR for PRA, ABO type, age, previous organ donation, DR genotype frequency, willingness to accept an ECD organ, gender, and cause of kidney disease (95% CI) | 1 | 0.95 (0.92–0.98) | 0.75 (0.73–0.78) | 0.84 (0.79–0.88) | 0.82 (0.75–0.90) |

| Adjusted for above plus OPO of listing (95% CI) | 1 | 1.04 (1.01–1.07) | 1.12 (1.08–1.17) | 1.34 (1.27–1.42) | 0.97 (0.89–1.07) |

CI, confidence interval; ECD, expanded criteria donor; HR, hazard ratio; OPO, organ procurement organization; PRA, panel reactive antibody; SRTR, Scientific Registry of Transplant Recipients.

Figure 2.

(A) Distribution of minority and Caucasian candidates in organ procurement organizations (OPOs) binned by quartiles of median waiting time for registrants to the Scientific Registry of Transplant Recipients (SRTR) between January 1, 2004 and December 31, 2007 by race/ethnicity. (B) Distribution of candidates by race/ethnicity and by OPOs binned by quartiles in median waiting time for registrants to the SRTR between January 1, 2004 and December 31, 2007.

Figure 3. Median waiting time for nonzero antigen mismatched deceased donor kidney transplant by race/ethnicity nationally and by quartile of median wait time for registrants in the Scientific Registry of Transplant Recipients between January 1, 2004 and December 31, 2007.

Brackets indicate 95% confidence intervals. Log-rank p-value for entire cohort is <0.0001.

Figure 4. Difference in median wait time between minority and Caucasian candidates for deceased donor kidney transplant by organ procurement organization (OPO) and nationally for registrants to the Scientific Registry of Transplant Recipients between January 1, 2004 and December 31, 2007, followed until February 28, 2011.

Individual chart bars represent the difference in median wait time between minority and Caucasian candidates within a single OPO. Of the 58 existing OPOs, 7 were excluded due to not containing enough Caucasian candidates (n = 1), due to incalculable median wait times in minorities and Caucasians (n = 2), due to incalculable median wait times in minorities (n = 2) and due to incalculable median wait times in Caucasians (n = 2).

Table 3 shows the serial adjustments using Cox proportional hazard modeling for all candidates waitlisted for renal transplant (covariate effects, Table S1) and for only those listed actively at time of waitlisting. The modeling was done in layers to show the proportionate effect of each layer of adjustment on the outcome of nonzero antigen mismatched deceased donor kidney transplant. Covariates in the first adjustment included gender, cause of ESRD and ABO type as well as factors used in the UNOS point system for allocation including age (extra points for pediatric recipients), PRA greater than 79%, previous organ donation, HLA-DR genotype frequency and willingness to accept an ECD organ. This first layer of adjustment only partially accounted for the racial disparities seen in our primary outcome of interest showing that nonzero antigen mismatch deceased donor transplantation was lower for African Americans (HR 0.94, CI 0.91–0.97), Hispanics (HR 0.73, CI 0.70–0.75), Asians and Pacific Islanders (HR 0.85, CI 0.81–0.89) and Other minority groups (HR 0.85, CI 0.79–0.93) compared to Caucasians (Table 3). The last layer of adjustment added OPO of listing to the previous model. Considering OPO of listing, African Americans (HR 1.03, CI 1.00–1.06) and Other minority groups (HR 1.00, CI 0.92–1.09) were transplanted at similar rates compared to Caucasians and Hispanics (HR 1.15, CI 1.10–1.19), whereas Asians and Pacific Islanders (HR 1.36, CI 1.30–1.43) were transplanted at superior rates compared to Caucasians. Overall, OPO of listing was the single most important factor accounting for the difference in waiting time for minorities, particularly for the Hispanic, Asian/Pacific Islander and other cohorts.

When performing the Cox regression modeling described above for only those candidates listed actively at the time of initial listing, the significance of OPO of listing was preserved. We additionally performed Cox regression analysis for nonzero antigen mismatched deceased donor kidney transplant for all registrants and also excluding pediatric registrants (age 17 years or younger) using OPO of listing as a random effect, as opposed to a fixed effect, and this did not substantially alter our findings (Table S2). Because living donor transplant and death would preclude a patient from deceased donor transplant and because these outcomes differed among the racial and ethnic groups, competing risk analyses for all registrants were performed adjusting for the same covariates as in the Cox regression (Table 4). These competing risk analyses were repeated excluding pediatric registrants and results were essentially unchanged (Table S3). Multiple sensitivity analyses support our conclusion that a strong association exists between OPO of listing and racial disparities in wait time to nonzero antigen mismatch deceased donor renal transplantation.

Table 4.

Time to deceased donor kidney transplant with and without inclusion of living donor transplant or death as a competing event from competing risk regression for all registrants to the SRTR between January 1, 2004 and December 31, 2007

| Caucasian (reference group) | African American | Hispanic | Asian/Pacific Islander | Other | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All deceased donor kidney transplants | |||||

| HR of deceased donor kidney transplant (95% CI) | 1 | 1.15 (1.12–1.18) | 1.25 (1.21–1.30) | 1.37 (1.31–1.44) | 1.13 (1.04–1.23); p-value 0.0027 |

| Nonzero antigen mismatch deceased donor kidney transplants only | |||||

| HR of nonzero antigen mismatch deceased donor kidney transplant (95% CI) | 1 | 1.38 (1.34–1.42) | 1.37 (1.32–1.43) | 1.68 (1.59–1.77) | 1.26 (1.15–1.37) |

CI, confidence interval; ECD, expanded criteria donor; HR, hazard ratio; OPO, organ procurement organization; PRA, panel reactive antibody; SRTR, Scientific Registry of Transplant Recipients.

Model adjusted for age, gender, etiology of kidney disease, previous kidney donation, willingness to accept ECD organ, PRA, ABO type, DR genotype frequency and OPO of listing.

All p-values <0.0001 unless otherwise specified.

Discussion

The current organ distribution system for deceased donor kidney transplantation is the product of historical alignments among transplant hospitals decades ago when the national transplant system was forming and demand for organs was less dire. Since that time the waitlist for kidney transplantation in the United States has grown, with more than 99 000 candidates waitlisted as of January 2014. Owing to this developmental anachronism, the current OPO organ distribution system has resulted in great variability in waiting time to transplant among the OPOs, with median wait times of just 10–11 months in OPOs with the shortest wait times compared to more than 72 months for those with the longest. This creates a system of great inequality, with some patients receiving organs in a relatively short period of time while others languish on the waitlist. Longer duration of exposure to dialysis correlates with worse outcomes for both patient and allograft after transplantation (24,25). Thus, patients living in areas with the longest wait times can expect less opportunity for transplantation, a greater chance of dying on the waitlist, worse outcomes should they receive a transplant and a shorter life span.

The Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network (OPTN) Final Rule states that organs should be allocated according to need and all barriers in access based on socioeconomic status and geography should be minimized in order to provide equitable care for all patients with end-stage organ failure (26). Despite carefully considered organ allocation policy changes, minorities waitlisted for renal transplantation remain disadvantaged compared with Caucasians. Our analyses show that OPO of listing is an important, if not the most important, contributor to unfavorable rates of transplantation for racial and ethnic minorities.

With the exception of zero antigen mismatch, deceased donor kidney transplants, which are shared nationally, the fundamental unit of organ distribution is the OPO. Interpreting the findings of our study from an OPO standpoint, the system appears fairer than previously thought. Disparities by race and ethnicity within most OPOs are much smaller than those seen nationally, suggesting that at a regional level the system is relatively blind to race and ethnicity. The data reveal that a significant root cause of racial disparities in kidney transplantation rates stems from the way the OPTN defines its allocation regions. At a national level, disparities will persist so long as arbitrary regional boundaries determine organ distribution.

The strength of our analysis is the large, national cohort of registry data which include nearly complete long-term follow-up of patient outcomes. By necessity it is an observational study, and we were unable to independently verify candidate characteristics such as race and ethnic group.

Our analysis also did not seek to examine the various practice patterns of organ usage at a transplant center or OPO level. This study can only evaluate transplant rates of those candidates waitlisted for transplant and does not take into account the myriad factors that affect access to transplantation and barriers to waitlisting that have been shown to disproportionately affect minority candidates. Previous reviews have shown increased use of nonideal organs in OPOs with less favorable wait times and this may disproportionately affect minorities (6–8,16–19).

Surprisingly, Hispanics, Asians and Pacific Islanders were transplanted at higher rates to Caucasians, African Americans and other minorities after adjusting for OPO of listing. We can only speculate on the reason for this. In our analysis, time to transplantation included both active and inactive time on the waiting list. Hall et al saw similar rates of referral but lower rates of waitlisting for Hispanics, and this waitlisted population may represent a relatively healthier cohort of patients (13). This study also found a lower prevalence of comorbidities including diabetes and cardiovascular disease among waitlisted Asians as compared to Caucasians and other racial groups. Based on these observations, we speculate that African Americans, Caucasians and other ethnic minorities were more likely to be inactive on the waiting list than Asians or Hispanics, explaining the superior rates of transplantation.

Our study also demonstrated that OPO of listing more profoundly affected waiting times for Hispanics, Asians, Pacific Islanders and other minorities than for African Americans. This likely results from the variable distribution of different racial and ethnic groups across the United States. Table 1 shows Hispanics and Asians/Pacific Islanders were more likely to be listed in OPOs with longer median waiting times. Thus, they are disproportionately affected by their OPO of listing. African Americans made up a smaller proportion of OPOs with shorter wait times but overall were distributed more evenly among the quartiles of OPO wait time and were less affected by their geographic location of listing indicating that other factors such as the distribution of ABO types are important in this population.

Our analysis shows that the uneven geographic distribution of minorities in the US population is a major contributor to the disproportionately longer waiting times seen nationally for minority candidates. Minorities were more likely to list in OPOs with long waiting times than Caucasian candidates. Our data would indicate that at an OPO level, the organ distribution system is relatively fair. That is to say, within most OPOs the differences in waiting times between minorities and Caucasians were generally small. Our results also show that waiting times for minorities cannot be significantly improved without addressing the major differences in waiting time created by the current OPO-based organ distribution system.

Supplementary Material

Table S1: Covariate effects on time to nonzero mismatched deceased donor kidney transplantation in the Cox proportional hazards model.

Table S2: Cox proportional hazards regression for nonzero antigen mismatched deceased donor transplantation for all registrants and for only adult registrants with OPO of listing as a random effect for registrants to the SRTR between January 1, 2004 and December 31, 2007.

Table S3: Time to deceased donor kidney transplant for adults (age >18 years) with and without inclusion of living donor transplant or death as a competing event for registrants to the SRTR between January 1, 2004 and December 31, 2007.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grant T32-DK072922. The data from the Scientific Registry of Transplant Recipients have been supplied by the Minneapolis Medical Research Foundation under contract with HHS/HRSA. The authors alone are responsible for reporting and interpreting these data; the views expressed herein are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the US Government.

Abbreviations

- CI

confidence interval

- ECD

expanded criteria donor

- ESRD

end-stage renal disease

- HR

hazard ratio

- OPO

organ procurement organization

- OPTN

Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network

- PRA

panel reactive antibody

- ref

reference covariate

- SRTR

Scientific Registry of Transplant Recipients

- std

standard deviation

- UNOS

United Network for Organ Sharing

Footnotes

Disclosure

The authors of this manuscript have no conflicts of interest to disclose as described by the American Journal of Transplantation.

Additional Supporting Information may be found in the online version of this article.

References

- 1.Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network (OPTN) and Scientific Registry of Transplant Recipients (SRTR) OPTN/SRTR 2011 annual data report. Rockville, MD: Department of Health and Human Services Health Resources and Services Administration, Healthcare; Systems Bureau, Division of Transplantation; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Crews DC, Charles RF, Evans MK, Zonderman AB, Powe NR. Poverty, race, and CKD in a racially and socioeconomically diverse urban population. Am J Kidney Dis. 2010;55:992–1000. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2009.12.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Patzer RE, McClellan WM. Influence of race, ethnicity and socioeconomic status on kidney disease. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2012;8:533–541. doi: 10.1038/nrneph.2012.117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Young BA. The interaction of race, poverty, and CKD. Am J Kidney Dis. 2010;55:977–980. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2010.04.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Keith D, Ashby VB, Port FK, Leichtman AB. Insurance type and minority status associated with large disparities in prelisting dialysis among candidates for kidney transplantation. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2008;3:463–470. doi: 10.2215/CJN.02220507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ayanian JZ, Cleary PD, Weissman JS, Epstein AM. The effect of patients’ preferences on racial differences in access to renal transplantation. N Engl J Med. 1999;341:1661–1669. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199911253412206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ayanian JZ, Cleary PD, Keogh JH, et al. Physicians’ beliefs about racial differences in referral for renal transplantation. Am J Kidney Dis. 2004;43:350–357. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2003.10.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Epstein AM, Ayanian JZ, Keogh JH, et al. Racial disparities in access to renal transplantation—Clinically appropriate or due to underuse or overuse? N Engl J Med. 2000;343:1537–1544. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200011233432106. 2 p preceding. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ashby VB, Kalbfleisch JD, Wolfe RA, et al. Geographic variability in access to primary kidney transplantation in the United States, 1996–2005. Am J Transplant. 2007;7:1412–1423. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2007.01785.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mathur AK, Ashby VB, Sands RL, Wolfe RA. Geographic variation in end-stage renal disease incidence and access to deceased donor kidney transplantation. Am J Transplant. 2010;10:1069–1080. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2010.03043.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tankersley MR, Gaston RS, Curtis JJ, et al. The living donor process in kidney transplantation: Influence of race and comorbidity. Transplant Proc. 1997;29:3722–3723. doi: 10.1016/s0041-1345(97)01086-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ojo A, Port FK. Influence of race and gender on related donor renal transplantation rates. Am J Kidney Dis. 1993;22:835–841. doi: 10.1016/s0272-6386(12)70343-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hall YN, Choi AI, Xu P, O’Hare AM, Chertow GM. Racial ethnic differences in rates and determinants of deceased donor kidney transplantation. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2011;22:743–751. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2010080819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gaston RS, Ayres I, Dooley LG, Diethelm AG. Racial equity in renal transplantation. The disparate impact of HLA-based allocation. JAMA. 1993;270:1352–1356. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Beatty PG, Mori M, Milford E. Impact of racial genetic polymorphism on the probability of finding an HLA-matched donor. Transplantation. 1995;60:778–783. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Alexander GC, Sehgal AR. Barriers to cadaveric renal transplantation among blacks, women, and the poor. JAMA. 1998;280:1148–1152. doi: 10.1001/jama.280.13.1148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Navaneethan SD, Singh S. A systematic review of barriers in access to renal transplantation among African Americans in the United States. Clin Transplant. 2006;20:769–775. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0012.2006.00568.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wolfe RA, Ashby VB, Milford EL, et al. Differences in access to cadaveric renal transplantation in the United States. Am J Kidney Dis. 2000;36:1025–1033. doi: 10.1053/ajkd.2000.19106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Young CJ, Gaston RS. Renal transplantation in black Americans. N Engl J Med. 2000;343:1545–1552. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200011233432107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Roberts JP, Wolfe RA, Bragg-Gresham JL, et al. Effect of changing the priority for HLA matching on the rates and outcomes of kidney transplantation in minority groups. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:545–551. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa025056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ashby VB, Port FK, Wolfe RA, et al. Transplanting kidneys without points for HLA-B matching: Consequences of the policy change. Am J Transplant. 2011;11:1712–1718. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2011.03606.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.U.S. Census Bureau. 2010 Census Redistricting Data (Public Law 94-171) Summary File, Tables P1 and P2 [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fine JP, Gray RJ. A proportional hazards model for the subdistribution of a competing risk. J Am Stat Assoc. 1999;94:496–509. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Meier-Kriesche HU, Kaplan B. Waiting time on dialysis as the strongest modifiable risk factor for renal transplant outcomes: A paired donor kidney analysis. Transplantation. 2002;74:1377–1381. doi: 10.1097/00007890-200211270-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Goldfarb-Rumyantzev A, Hurdle JF, Scandling J, et al. Duration of end-stage renal disease and kidney transplant outcome. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2005;20:167–175. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfh541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network. Health resources and services administration, HHS. Final rule Fed Regist. 1999;64:56650–56661. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table S1: Covariate effects on time to nonzero mismatched deceased donor kidney transplantation in the Cox proportional hazards model.

Table S2: Cox proportional hazards regression for nonzero antigen mismatched deceased donor transplantation for all registrants and for only adult registrants with OPO of listing as a random effect for registrants to the SRTR between January 1, 2004 and December 31, 2007.

Table S3: Time to deceased donor kidney transplant for adults (age >18 years) with and without inclusion of living donor transplant or death as a competing event for registrants to the SRTR between January 1, 2004 and December 31, 2007.