Abstract

Purpose

The Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) program is an important epidemiologic research tool to study cancer. No information is available on its pathologic accuracy for renal cell carcinoma (RCC).

Methods

Central pathology review was analyzed as a part of the United States Kidney Cancer Study. Cases previously identified through the Detroit SEER registry were reviewed. The sensitivity and specificity, and positive and negative predictive values were calculated for each SEER-assigned subtype, with the central review assignments used as the reference.

Results

Of the 498 cases included in this study, 490 (98.5%) were confirmed to be RCC. The overall agreement for histology was 78.2% (k = 0.55); however, individual cases were frequently reclassified. The sensitivity and specificity for SEER-assigned clear cell RCC were 79.1% and 88.1%, respectively, when based solely on the ICD-O-3 morphology code 8310 (n = 310), and 99.2% and 80.5% when 8312 (RCC not otherwise specified; n = 41) was also assumed to be clear cell. Although RCC not otherwise specified is frequently grouped with clear cell, only 78.1% had this histology. Assignments of papillary and chromophobe RCC had comparable sensitivities (73.5% and 72.4%, respectively) and specificities (97.5% and 97.6%). Positive predictive values for clear cell (excluding/including 8312), papillary, and chromophobe RCC were 95.5%/93.5%, 85.9%, and 65.6%, respectively.

Conclusions

Our findings confirm that nearly all RCC cases are correctly classified in SEER. The positive predictive value was higher for clear cell RCC than for papillary or chromophobe RCC, suggesting that pathologic confirmation may be warranted for studies of non–clear cell tumors. Published by Elsevier Inc.

Keywords: RCC, SEER, Histology, Pathology, Concordance, Accuracy

1. Introduction

In recent years, the urologic oncology community has utilized the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) program to better understand the etiology of renal cell carcinoma (RCC) and evaluate treatment strategies. The large number of patients included in SEER registries can be ideal for the studies of rare cancers or unusual subtypes. To ensure high quality, the SEER program implemented strenuous testing, including biannual case finding, recoding, and reliability studies in addition to educational and training programs [1]. Despite these efforts, pathology reporting practices may have a greater influence on data quality than variability in chart abstraction. According to SEER coding rules, cancer type and histology should be gathered primarily from the pathology or cytology report or both. Registry medical abstractors are also instructed to gather additional information from the medical records and operative reports. Although the College of American Pathology sets forth specific organ/cancer site guidelines for reporting, significant deficiencies in pathologic reporting exist [2,3]. SEER histology coding greatly depends on the pathologist, but currently, there is no method of pathologic data auditing.

In 2004, a study of lung cancer histology in SEER determined that an independent slide review may be required for the precise designation of histologic subtype [4]. Since then, no additional studies have assessed the accuracy of SEER pathology reporting. We set out to determine the accuracy of reporting of RCC histology in SEER compared with an independent pathologic review of cases included in the United States Kidney Cancer Study (USKC).

2. Methods

We utilized existing data from the USKC, a large case-control study that was conducted in Detroit, MI and Chicago, IL between February 2002 and January 2007 [5]. For the purposes of this analysis, USKC cases with reported ICD-O-3 histology in the Detroit SEER registry were selected for comparison with histologic classifications in a central pathology review. All available nephrectomy specimens had 1 to 3 of the most representative hematoxylin and eosin–stained slides sent to the National Cancer Institute for review by an expert kidney cancer pathologist (MM), who was blinded to SEER histology. In the central review, RCC histology was designated according to the Union Internationale Contre le Cancer/American Joint Committee on Cancer recommendations [6]. Although papillary renal tumors were broken into subtypes in this review, for our analysis, they were grouped together to compare to the SEER registry. The available tissue specimens were insufficient to appropriately identify histologic subtype for 32 cases, which were considered “unclassifiable” and excluded from all analyses. Lesions such as benign renal cysts, transitional cell carcinoma, or oncocytomas were considered “not RCC.”

Patient demographics and tumor histology classifications in both SEER and the central pathology review were available for 498 cases. An agreement between reported histology in SEER and the central pathology review was analyzed overall and by individual histology. Central pathology review was considered the gold standard for the histologic classification. For each histologic type, we dichotomized cases (e.g., clear cell RCC vs. other) and calculated the percent agreement; sensitivity (e.g., the percentage of cases identified as clear cell RCC in the central pathology review that were correctly classified as such in SEER); specificity (e.g., the percentage of cases identified as non–clear cell RCC in the central review that were classified as non–clear cell in SEER); positive predictive value (PPV; e.g., the percentage of cases coded as clear cell RCC in SEER that were confirmed as such in the central pathology review); and negative predictive value (NPV; e.g., the percentage of cases coded as non–clear cell RCC in SEER that were confirmed as such in the central review). For each histologic type, the McNemar testing was used to check for differential misclassification.

3. Results

Of the 498 cases included in this analysis, 490 (98.5%) were confirmed to be RCC in the central pathology review. Over half of the cases that were included were male (55.4%) and most were non-Hispanic whites (72.9%; Table 1). Table 2 demonstrates the distribution of confirmed RCC cases with classifiable histology in both SEER and the central pathology review (n = 490). According to SEER, 310 cases (63.3%) were clear cell, 71 (14.5%) were papillary, 32 (6.5%) were chromophobe, 36 (7.4%) were other RCC, and 41 (8.4%) were RCC not otherwise specified (NOS). Several studies have included RCC NOS (ICD-O-3 morphology code 8312) with clear cell, and if included, 351 (71.6%) would be classified with clear cell histology. Central pathology review classified clear cell, papillary, chromophobe, and other RCC in 372 (75.9%), 83 (16.9%), 29 (5.9%), and 6 (1.2%) cases, respectively. For the 32 cases considered unclassifiable and excluded from this analysis, 17 (53.1%) were reported in SEER as RCC NOS or “other RCC” histology.

Table 1.

Patient demographic information (n = 498)a

| Characteristic | n, % |

|---|---|

| Sex | |

| Female | 222 (44.6) |

| Male | 276 (55.4) |

| Race | |

| White | 363 (72.9) |

| Black | 135 (27.1) |

| Age at diagnosis | |

| <45 | 65 (13.1) |

| 45–54 | 127 (25.5) |

| 55–64 | 162 (32.5) |

| 65–74 | 109 (21.9) |

| 75+ | 35 (7.0) |

Excludes patients with “unclassifiable” RCC histology in the pathology review.

Table 2.

RCC histologic subtypes in SEER and central pathology review (n = 490)a

| Histology | SEER n, % | Pathology review n, % |

|---|---|---|

| Clear cell | 310 (63.3) | 372 (75.9) |

| Including NOSb | 351b (71.6) | |

| Papillary | 71 (14.5) | 83 (16.9) |

| Chromophobe | 32 (6.5) | 29 (5.9)c |

| Other RCC | 36 (7.4)d | 6 (1.2)e |

| RCC NOS | 41 (8.4) | – |

Excludes patients with non-RCC and “unclassifiable” RCC histology in the pathology review.

Includes all 312 clear cell RCC cases and the 41 cases classified as RCC NOS (8312).

Includes cases identified as either chromophobe or hybrid oncocytic neoplasms.

Other in medical abstract data includes the following cases: 24 cyst-associated RCC (8316); 12 adenocarcinoma with mixed subtypes (8255); 2 collecting duct carcinoma (8319); and 2 granular cell carcinoma (8320).

Other in central pathology review data includes the following cases: 4 multilocular cystic RCC; 1 collecting duct carcinoma; and 1 neuroendocrine tumor.

The agreement between reported histology in SEER and the corresponding histology in the central review is demonstrated in Table 3. For the overall case distribution, the exact agreement depended on how RCC NOS was defined. Including this category with clear cell led to an 84.7% exact agreement (k = 0.64). Considering the NOS cases separately, there was a 78.2% exact agreement (k = 0.55). Overall, the agreement for the distributions of individual histologic types ranged from 81.6% for clear cell to 96% for chromophobe.

Table 3.

Overall histologic distribution for identifiable RCC cases (n = 490)

| Exact agreement, % | κ | |

|---|---|---|

| Overall (NOS separate) | 78.20 | 0.55 |

| Overall (NOS in clear cell group) | 84.70 | 0.64 |

| Clear cell | 81.60 | 0.57 |

| Including NOS | 86.30 | 0.65 |

| Papillary | 93.50 | 0.75 |

| Chromophobe | 96.10 | 0.67 |

| Other RCC | 93.50 | 0.22 |

Table 4 shows the individual case distribution by SEER and central pathology review. Despite strong agreement in the overall histologic distribution, individual cases were frequently reclassified by central review. The percent agreement, sensitivity, specificity, PPV, NPV, and P value for differential misclassification (the McNemar test) were calculated for cases reported by SEER (Table 5). SEER classification of clear cell histology had excellent PPV (95.5%); however, the NPV was fairly low (57.8%) as many non–clear SEER cases became reclassified as clear cell RCC. Combining the SEER RCC NOS with clear cell decreased the PPV to 93.5%, as only 78.1% of these cases were classified as clear cell. Relative to clear cell cases, those classified in SEER as papillary RCC had a lower PPV (85.9%) but a much higher NPV (94.8%). Of the major histologic categories, SEER chromophobe has the lowest PPV (65.6%) but had the highest NPV (98.3%). The other RCC categories were frequently reclassified, leading to a very poor PPV (13.9%). Clear cell, papillary, chromophobe, and other RCC had a sensitivity of 79.6%, 73.5%, 72.4%, and 83.3% and a specificity of 88.1%, 97.5%, 97.6%, and 93.6%, respectively. Including RCC NOS in the clear cell category improved sensitivity (88.2%) but decreased specificity (80.5%). The McNemar tests demonstrated a significant, non-random misclassification for clear cell, RCC NOS, papillary, and other RCC. Clear cell RCC had misclassification of other cases toward clear cell, whereas the other categories had a misclassification toward a new category.

Table 4.

Frequencies by histologic subtype in SEER data and central pathology review data (n = 498)a

| SEER | Pathology review

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clear cell | Papillary | Chromophobeb | Otherc | Not RCC | |

| Clear cell | 296 | 10 | 4 | 0 | 2 |

| Papillary | 9 | 61 | 1 | 0 | 2 |

| Chromophobe | 7 | 4 | 21 | 0 | 0 |

| Otherd | 28 | 3 | 0 | 5 | 4 |

| RCC NOS | 32 | 5 | 3 | 1 | 0 |

Excludes cases that were “unclassifiable” in the pathology review on account of limitations in material available for review.

Includes cases identified as either chromophobe or hybrid oncocytic neoplasms.

Other in central pathology review data includes the following cases: 4 multilocular cystic RCC; 1 collecting duct carcinoma; and 1 neuroendocrine tumor.

Other SEER data includes the following cases: 24 cyst-associated RCC (8316); 12 adenocarcinoma with mixed subtypes (8255); 2 collecting duct carcinoma (8319); 2 granular cell carcinoma (8320); and sarcomatoid (8318).

Table 5.

Agreement between classifiable RCC histologic subtypes (n = 490)a

| Histology | Sensitivity | Specificity | PPV | NPV | P valued |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clear cell | 79.6 | 88.1 | 95.5 | 57.8 | <0.001 |

| Including NOSb | 88.2 | 80.5 | 93.5 | 68.4 | 0.01 |

| Papillary | 73.5 | 97.5 | 85.9 | 94.8 | 0.03 |

| Chromophobe | 72.4 | 97.6 | 65.6 | 98.3 | 0.49 |

| Other RCCc | 83.3 | 93.6 | 13.9 | 99.8 | <0.001 |

Excludes cases that were non-RCC or “unclassifiable” RCC histology in the pathology review.

Includes all 312 clear cell RCC cases and the 41 cases classified as RCC NOS (8312) in SEER.

Other in medical abstract data includes the following cases: 24 cyst-associated RCC (8316); 12 adenocarcinoma with mixed subtypes (8255); 2 collecting duct carcinoma (8319); and 2 granular cell carcinoma (8320). Other in central pathology review data includes the following cases: 4 multilocular cystic RCC; 1 collecting duct carcinoma; and 1 neuroendocrine tumor.

Two-sided McNemar test.

4. Discussion

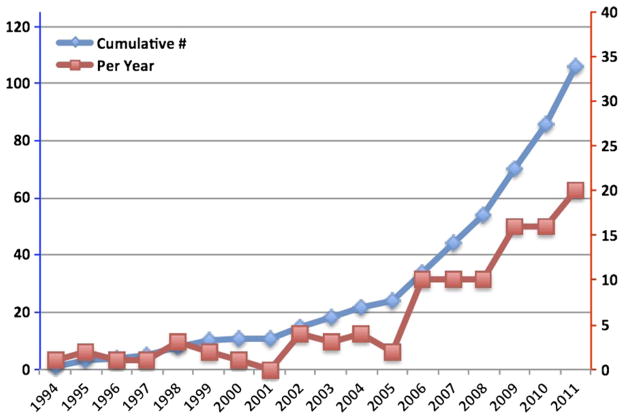

Although the SEER-based data sets have been available for some time, only recently has there been widespread use for kidney cancer research. As of 2012, more than 100 kidney cancer publications using SEER data are now available, a number on track to double in the next 5 years (Fig. 1). Despite extensive efforts to standardize and educate SEER registry participants performing extraction/ coding, there are inherent issues with pathology assessment, especially in kidney cancer [3]. These are deficiencies that may not be overcome by registry efforts and rely, instead, on education by the pathology community on the essential elements in pathology reporting and current histologic classification.

Fig. 1.

Number of SEER-based kidney cancer publications identified in SEER from 1994 to 2011 (per year: red/right axis and cumulative value: blue/left axis). We searched PUBMED for kidney cancer publications using terms “SEER” and “renal cell carcinoma” or “kidney cancer.” Selected articles were reviewed, and only original research articles were included in the analysis.

Epidemiologic data looking at cancer incidence, mortality, geographic distribution, and treatment trends rely on cancer being accurately designated as RCC when warranted. Landmark studies using SEER data include several demonstrating a rising incidence in kidney cancer [7,8]. To validate prior and future research endeavors involving SEER data sets, we reviewed the accuracy of designated RCC cases. Our data confirm that nearly 99% of reported cases are RCC, supporting the use of SEER for epidemiologic RCC research.

Research involving SEER has expanded to the study of kidney tumor behavior. Recent publications explore the clinical aggressiveness of specific histologic types [9–11]. Despite these correlative pathologic studies, no data support the accuracy of SEER for this type of research, as no central pathology review has been analyzed previously for kidney cancer, let alone any genitourinary tract malignancy. To determine whether SEER could be used to answer biologic questions for specific histologic types of RCC, we analyzed data from an existing study that relied on both SEER and a central pathology review by an expert in kidney cancer pathology.

The overall histologic agreement depended on how RCC NOS was categorized, a SEER classification that accounted for 7.4% of the cases. It is unclear why some groups have included NOS with clear cell tumors in prior studies. As there is no SEER code for “RCC unclassified,” RCC NOS just as easily could represent this histology or represent a deficiency in either medical extraction or pathologic reporting practices. Pathology review of the NOS category found that almost a quarter of these cases are non–clear cell histology. Prior studies evaluating histology that have combined this category with clear cell RCC must be interpreted with caution. Moving forward, researchers should think about the study question carefully, prior to using the SEER 8312 (RCC NOS) code.

Although multiple studies debate whether histology is an independent predictor of prognosis, there is no debate that histologic type provides insight into tumor biology. Clear cell, papillary, and chromophobe RCC differ in regard to common chromosomal changes and gene alterations. Using the SEER database to analyze differences in clinical behavior between subtypes is an exciting prospect. For clear cell RCC, the use of SEER for detailed histologic analyses appears valid as we confirmed histology in over 95% of SEER clear cell tumors. Relative to clear cell tumors, the proportion of cases classified as papillary or chromophobe in SEER that were confirmed as such in the central pathology review was lower (85.9% and 65.6%, for papillary and chromophobe, respectively). For each histologic subtype, the sensitivity and specificity varied. Depending on the research question, it may be necessary to confirm SEER histologic coding to properly select patients for analysis.

In our review of histology, the decreased PPV for the non–clear cell tumors was not surprising, as often pathologists have difficulty distinguishing eosinophilic tumors based on hematoxylin and eosin alone. Additional studies such as immunohistochemistry may be necessary, but are not always available [12]. Designation of papillary histology can be problematic for many tumors that appear to fit into more than 1 category. Papillary histology requires > 75% of the tumor having a papillary configuration; however, clear cell tumors can also have this morphologic configuration [13,14]. The PPV for SEER chromophobe RCC was the lowest among the major subtypes with approximately a third of tumors being reclassified on independent review. Chromophobe tumors frequently can present a diagnostic challenge to pathologists and exist in 2 variants, classic and eosinophilic types [12,15]. These findings raise concerns over SEER research aimed at studying the biology of non–clear cell tumors, especially for chromophobe RCC.

Several limitations of this study must be addressed. Our analysis is only from 1 individual SEER registry, and it is possible that there are regional differences in reporting practices. Coordinating a review of multiple registries is a difficult task and may only be possible with an internal effort from SEER for quality control. Another limitation in our analysis is due to the fact that SEER only tracks malignant tumors, and therefore, it is not possible to review tumors that may have been inaccurately classified as benign. Additionally, assessment of other pathologic criteria, such as T stage and nuclear grade, could not be accurately carried out with our central review methodology. Properly reviewing T stage may require assessment of the gross specimen, something not feasible in a large central review. Nuclear grade review also could not be accurately assessed from the small number of slides provided. Current guidelines require the highest grade present to be assigned the final nuclear grade, and we were concerned our methodology would introduce bias toward undergrading. Finally, there is no way to rule out errors in medical extraction, and the discrepancy in non–clear cell tumors is likely due to differences in local pathology histologic classification.

The clinical implications of proper pathology reporting are significant as histology-specific therapy is on the horizon [16]. In the future, prior to placing a patient on pathway-specific therapy, it may be warranted to get a second opinion on histology, particularly for non–clear cell diagnoses. In other oncologic fields, a pathologic second opinion has been shown to alter management strategy [17].

5. Conclusions

SEER-based kidney cancer research is becoming more common in recent years, and urologic oncologists are using this database to ask biologic questions. To date, there has been no review of pathologic accuracy for any genitourinary tract malignancy. We found that almost 99% of cases were correctly classified as RCC. The sensitivity and PPV were higher for cases classified in SEER as clear cell tumors than for papillary or chromophobe tumors. RCC NOS, although frequently grouped with clear cell tumors, frequently represents non–clear cell histology. For studies assessing non–clear cell renal tumors, pathologic confirmation may be warranted to ensure accurate classification.

Acknowledgments

Supported by the Intramural Research Program of the National Institutes of Health, National Cancer Institute, Center for Cancer Research.

Footnotes

Funding: NCI Intramural funding.

Financial disclosures

None.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Institute, U. N. I. o. H. N. C. Surveillance epidemiologic and end result: quality improvement tools. Bethesda, MD: 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bull AD, Biffin AH, Mella J, et al. Colorectal cancer pathology reporting: a regional audit. J Clin Pathol. 1997;50:138. doi: 10.1136/jcp.50.2.138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shuch B, Pantuck AJ, Pouliot F, et al. Quality of pathological reporting for renal cell cancer: implications for systemic therapy, prognostication and surveillance. BJU Int. 2011;108:343. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2010.09871.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Field RW, Smith BJ, Platz CE, et al. Lung cancer histologic type in the surveillance, epidemiology, and end results registry versus independent review. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2004;96:1105. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djh189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Colt JS, Schwartz K, Graubard BI, et al. Hypertension and risk of renal cell carcinoma among white and black Americans. Epidemiology. 2011;22:797. doi: 10.1097/EDE.0b013e3182300720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Storkel S, Eble JN, Adlakha K, et al. Classification of renal cell carcinoma: Workgroup no. 1. Union Internationale Contre le Cancer (UICC) and the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) Cancer. 1997;80:987. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0142(19970901)80:5<987::aid-cncr24>3.0.co;2-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chow WH, Devesa SS, Warren JL, et al. Rising incidence of renal cell cancer in the United States. J Am Med Assoc. 1999;281:1628. doi: 10.1001/jama.281.17.1628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hollingsworth JM, Miller DC, Daignault S, et al. Rising incidence of small renal masses: a need to reassess treatment effect. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2006;98:1331. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djj362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rothman J, Egleston B, Wong YN, et al. Histopathological characteristics of localized renal cell carcinoma correlate with tumor size: a SEER analysis. J Urol. 2009;181:29. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2008.09.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Didwaniya N, Edmonds RJ, Fang X, et al. Survival outcomes in metastatic renal carcinoma based on histological subtypes: SEER database analysis. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29(suppl 7) abstr 381. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Keegan KA, Schupp CW, Chamie K, et al. Histopathology of surgically treated renal cell carcinoma: survival differences by subtype and stage. J Urol. 2012 doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2012.04.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Liu L, Qian J, Singh H, et al. Immunohistochemical analysis of chromophobe renal cell carcinoma, renal oncocytoma, and clear cell carcinoma: an optimal and practical panel for differential diagnosis. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2007;131:1290. doi: 10.5858/2007-131-1290-IAOCRC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gobbo S, Eble JN, Grignon DJ, et al. Clear cell papillary renal cell carcinoma: a distinct histopathologic and molecular genetic entity. Am J Surg Pathol. 2008;32:1239. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e318164bcbb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kovacs G, Wilkens L, Papp T, et al. Differentiation between papillary and nonpapillary renal cell carcinomas by DNA analysis. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1989;81:527. doi: 10.1093/jnci/81.7.527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Finley DS, Shuch B, Said JW, et al. The chromophobe tumor grading system is the preferred grading scheme for chromophobe renal cell carcinoma. J Urol. 2011;186:2168. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2011.07.068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Linehan WM. The genetic basis of kidney cancer: implications for management and use of targeted therapeutic approaches. Eur Urol. 2012 doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2012.02.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Staradub VL, Messenger KA, Hao N, et al. Changes in breast cancer therapy because of pathology second opinions. Ann Surg Oncol. 2002;9:982. doi: 10.1007/BF02574516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]