Abstract

Objective

To investigate the diagnostic performance of computed tomography angiography (CTA) in identifying the cause of bleeding and to determine the clinical features associated with a positive test result of CTA in patients visiting emergency department with overt gastrointestinal (GI) bleeding.

Materials and Methods

We included 111 consecutive patients (61 men and 50 women; mean age: 63.4 years; range: 28-89 years) who visited emergency department with overt GI bleeding. They underwent CTA as a first-line diagnostic modality from July through December 2010. Two radiologists retrospectively reviewed the CTA images and determined the presence of any definite or potential bleeding focus by consensus. An independent assessor determined the cause of bleeding based on other diagnostic studies and/or clinical follow-up. The diagnostic performance of CTA and clinical characteristics associated with positive CTA results were analyzed.

Results

To identify a definite or potential bleeding focus, the diagnostic yield of CTA was 61.3% (68 of 111). The overall sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value (PPV), and negative predictive value were 84.8% (67 of 79), 96.9% (31 of 32), 98.5% (67 of 68), and 72.1% (31 of 43), respectively. Positive CTA results were associated with the presence of massive bleeding (p = 0.001, odds ratio: 11.506).

Conclusion

Computed tomography angiography as a first-line diagnostic modality in patients presenting with overt GI bleeding showed a fairly high accuracy. It could identify definite or potential bleeding focus with a moderate diagnostic yield and a high PPV. CTA is particularly useful in patients with massive bleeding.

Keywords: Computed tomography angiography, Overt gastrointestinal bleeding, Diagnostic performance

INTRODUCTION

Overt gastrointestinal (GI) bleeding is defined as GI bleeding with visible bright red or altered blood in emesis or feces (1). It is a medical emergency that can cause major morbidity and mortality (2). Although the diagnosis and treatment of GI bleeding have advanced recently, mortality rate for patients with acute GI bleeding has not changed, ranging from 8% to 14%. It may increase up to 40% in severe cases (3, 4). Recently, gastroduodenoscopy has been considered as a primary diagnostic modality in patients with acute upper GI bleeding. Colonoscopy is becoming the most frequently used examination for patients with lower GI bleeding (5). During endoscopic examinations, however, the presence of blood clots as well as residual food materials or feces may hinder the visualization of the bleeding point (6). For patients with suspected lower GI bleeding, bowel preparation that may delay the procedure for several hours is not always feasible in cases of massive bleeding (7). A recent study reported that endoscopy or subsequent workup failed to identify specific cause of bleeding in 14% of patients with upper GI bleeding and 20% of patients with lower GI bleeding (8).

Some studies (9, 10, 11, 12) have shown good diagnostic performance of multidetector computed tomography (CT) in patients with GI bleeding. According to the results from a recent meta-analysis (13), the overall sensitivity and specificity of CT angiography (CTA) for detecting acute GI bleeding were 85.2% and 92.1%, respectively, with wide variability, ranging from 33.3% to 100% for sensitivity and 0% to 100% for specificity. However, as a first-line diagnostic modality in patients with overt GI bleeding, the diagnostic performance of CTA has not been fully assessed either for definite or for possible bleeding focus. Therefore, the purpose of this study was to investigate the diagnostic performance of CTA as a first-line diagnostic modality in identifying definite or possible causes of bleeding and clinical features associated with positive test result of CTA in patients with overt GI bleeding.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patient Selection

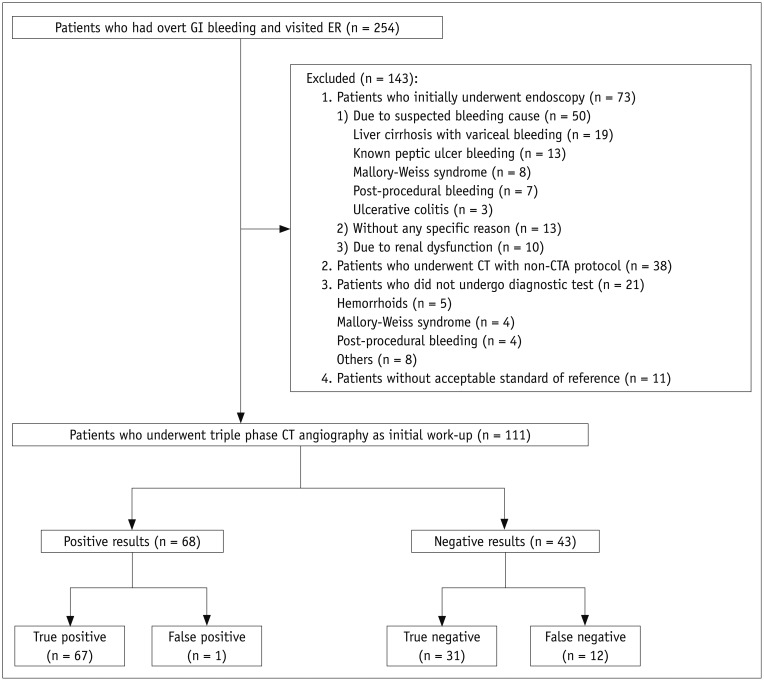

Our Institutional Review Board approved this study and waived the requirement of informed patient consent. Using the hospital's medical record database, we retrospectively searched for adult patients (age > 18 years) who visited the emergency department of our hospital for overt GI bleeding and underwent CT from July to December 2010. Through this period, a total of 254 adult patients visited the emergency department of our hospital with overt GI bleeding. Among them, 143 patients were excluded from this study, including those who initially underwent endoscopy (n = 73), underwent CT with non-triple phase CTA protocol (n = 38), did not undergo any diagnostic test (n = 21), or were lack of acceptable standard of reference (n = 11). Finally, 111 patients (mean age: 63.4 years; range: 17-91 years) who underwent triple phase CTA as a first-line examination after visiting the emergency department were included in this study. A flow diagram depicting the outcome of 111 patients included in our study is shown in Figure 1. Clinical and demographic characteristics of included and excluded patients are summarized in Table 1.

Fig. 1. Flow diagram and outcome of 111 patients with overt gastrointestinal (GI) bleeding.

CTA = CT angiography, ER = emergency room

Table 1. Clinical Characteristics of Patients with Overt GI Bleeding.

| Clinical Feature | Patients Included | Patients Excluded | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (yr) | 0.104 | ||

| ≤60 | 43 | 70 | |

| ≥61 | 68 | 73 | |

| Sex | 0.103 | ||

| Female | 50 | 50 | |

| Male | 61 | 93 | |

| Bleeding type | <0.001 | ||

| Upper | 31 | 113 | |

| Lower | 80 | 30 | |

| Bleeding episode | 0.083 | ||

| Initial | 95 | 110 | |

| Recurrent | 16 | 33 | |

| Recent bleeding | 0.882 | ||

| Present | 67 | 85 | |

| Absent | 44 | 58 | |

| Massive bleeding | 0.554 | ||

| Present | 30 | 34 | |

| Absent | 81 | 109 | |

| Severe anemia | 0.389 | ||

| Present | 46 | 67 | |

| Absent | 65 | 76 | |

| DM | 0.243 | ||

| Present | 19 | 33 | |

| Absent | 92 | 110 | |

| HTN | 0.799 | ||

| Present | 46 | 57 | |

| Absent | 65 | 86 | |

| CVD | 0.186 | ||

| Present | 16 | 13 | |

| Absent | 95 | 130 | |

| Vascular disease | 0.130 | ||

| Present | 54 | 56 | |

| Absent | 57 | 87 |

CVD = cerebrovascular disease, DM = diabetes mellitus, GI = gastrointestinal, HTN = hypertension

CT Protocol

Triple-phase CTA was performed using a 64- (n = 49) or 256- (n = 62) channel multidetector CT scanner (Brilliance 64 or iCT 256; Philips Medical Systems, Cleveland, OH, USA). After obtaining non-enhanced images, intravenous contrast agent (2 mL/kg; iopromide, Ultravist 370; Bayer, Berlin, Germany) was administered via antecubital vein using a power injector (Stellant D, Medrad, Indianola, PA, USA) at a rate of 4 mL/sec.

Bolus-tracking software (Brilliance; Philips Medical Systems, Cleveland, OH, USA) was used to initiate arterial phase scanning 15 seconds after enhancing the abdominal aorta to a 200 Hounsfield units threshold. Portal venous phase scanning was obtained with a fixed scan delay of 60 seconds after the beginning of contrast material injection. The scan range of all three phases was from the diaphragm to the symphysis pubis in a supine position. Helical scan data were acquired using 64 × 0.625 mm or 2 × 128 × 0.625 mm collimation, a rotation speed of 0.5 seconds, a pitch of 0.891 or 0.993, and 120 kVp. Effective mAs ranged from 125 to 460 mAs using an automatic tube current modulation technique (Dose-Right; Philips Medical Systems, Cleveland, OH, USA). Transverse and coronal section datasets for the three phases were reconstructed with a section of 4-mm thickness at 3-mm increments.

CT Findings and Clinical Characteristics Analysis

Two abdominal radiologists (with 13 and 2 years of experience in the field of abdominal radiology, respectively) retrospectively reviewed the CT images and reached a consensus. Both reviewers were aware that all patients had overt GI bleeding. However, they were blinded to any clinical information, including patients' symptoms, follow-up results, and the results of endoscopic or other diagnostic examinations. All images were reviewed in stack mode on a Picture Archiving and Communications System workstation (INFINITT Technology Co., Seoul, Korea).

The reviewers determined by consensus whether there was any definite or potential bleeding focus through the GI tract. A definite bleeding focus included lesions with active contrast material extravasation in the GI tract on arterial or portal venous phase images compared to non-enhanced CT images or obvious vascular lesions such as pseudoaneurysms. A potential bleeding focus was defined as a lesion known to be associated with GI bleeding, such as ulceroinflammatory lesion or a mass in the GI tract other than a definite bleeding focus (10).

An investigator who was not involved in CTA finding analysis reviewed the medical records to determine the clinical characteristics of all patients. Patients' demographics and patterns of bleeding such as upper versus lower GI bleeding, initial or recurrent bleeding, recent or non-recent bleeding, and massive or non-massive bleeding were determined. Bleeding was considered to have an upper GI origin when a certain patient's manifestation was hematemesis or melena. It was considered to be of a lower GI origin when it was hematochezia. Recent bleeding was defined as having episodes of GI bleeding within 24 hours before undergoing CTA in our hospital. Massive bleeding was defined as the presence of either of the following two criteria: the patients required transfusion of at least 4 units of blood during a 24-hour period in the hospital, or they had hemodynamic instability such as hypotension with systolic blood pressure of less than 90 mm Hg (12). The presence of moderate-to-severe anemia and the presence of comorbidities including diabetes, hypertension, cerebrovascular disease (CVD), and underlying vascular disease such as atherosclerotic change and vasculitis were also determined. Moderate-to-severe anemia was defined as a hemoglobin level less than 10 mg/dL at the initial blood test before transfusion.

Reference Standard

Other diagnostic studies following CTA were performed within 24 hours in 93 patients (83.8%). The remaining 18 patients were clinically followed up for a median of 34 months (range, 6 to 51 months). The median follow-up period for the 111 patients was 18 months (range, 0 to 51 months). One investigator who was not involved in CT image interpretation or medical record review reviewed all available subsequent studies. Of the 93 patients who underwent following procedures within 24 hours, 3 underwent surgeries, 27 underwent conventional angiography alone, 9 underwent conventional angiography and gastroduodenoscopy, and the remaining 54 underwent endoscopic examinations, including colonoscopy (n = 29) and gastroduodenoscopy (n = 25). After 24 hours, small-bowel follow-through (n = 12), 99mTc-labeled red blood cell scanning (n = 12), colonoscopy (n = 11), and gastroduodenoscopy (n = 16) were performed for the remaining 18 patients. Clinical data from the 111 patients were also reviewed by the investigator. In this way, a reference standard was built and the diagnostic performance of CTA was assessed using criteria (Table 2) modified from those used in previous studies (10, 14).

Table 2. Criteria Used to Determine Diagnostic Performance of CTA.

| Category | Criteria |

|---|---|

| True positive | Confirmation of CTA diagnosis at further work-up |

| True negative | Verification of negative CTA results by means of negative endoscopic examination, angiography, small-bowel follow-through, or 99mTc-labeled red blood cell scanning results and bleeding resolving without treatment OR by means of spontaneous cessation and no recurrence of bleeding with no further treatment during follow-up period of at least 6 months |

| False positive | Positive CTA results with negative results or different source of bleeding found at endoscopic examination, angiography, small-bowel follow-through, or 99mTc-labeled red blood cell |

| False negative | Negative CTA results with cause of bleeding diagnosed after further work-up OR negative CTA results with persistent or recurrent bleeding |

| Unverified | Any other case |

CTA = CT angiography, OR = odds ratio

Statistical Analysis

We evaluated the sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value (PPV), and negative predictive value (NPV) of CTA for identifying a definite or potential cause of bleeding. We also analyzed any association of patients' demographics or various clinical features with CTA to determine the cause of positive bleeding using univariable and multivariable logistic regression analyses. For these analyses, patients' demographics and clinical features including age, sex, pattern of bleeding (upper or lower, initial or recurrent, and massive or non-massive bleeding), the presence of moderate-to-severe anemia, and the presence of comorbidities such as diabetes, hypertension, CVD, or underlying vascular disease were used. All variables with a p value less than 0.25 in univariable analysis were included in the subsequent multivariable analysis. IBM SPSS Statistics version 20 (IBM, Armonk, NY, USA) was used to perform all statistical analyses. Statistical significance was considered when p value was less than 0.05.

RESULTS

CT Angiography Results

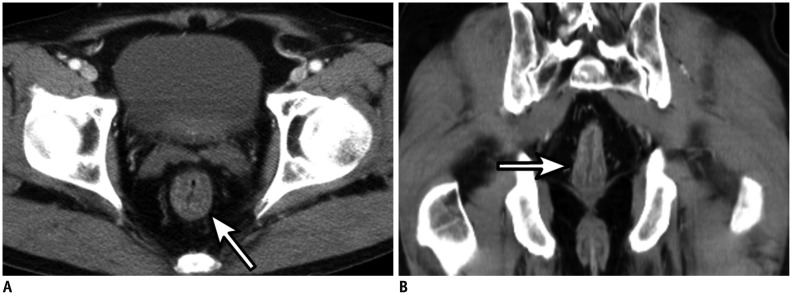

Of the 111 patients, 23 (20.7%) with overt GI bleeding had definite bleeding foci on CTA. The anatomical locations of the bleeding foci included stomach (n = 9), colon (n = 5) (Fig. 2), esophagus (n = 3), rectum (n = 2), duodenum (n = 2), and jejunum or ileum (n = 2). All 23 patients showed definite bleeding foci in reference standard examinations, including gastroscopy (n = 7), colonoscopy (n = 2), angiography (n = 10), 99mTc-labeled red blood cell scan (n = 2), and surgery (n = 2). CTA failed to demonstrate a definite bleeding focus in one patient who had confirmed hemorrhagic gastritis with active bleeding on gastroscopy.

Fig. 2. 79-year-old male patient with hematochezia and severe anemia.

A, B. Axial arterial phase (A) and coronal portal venous phase (B) CT angiography showing definite bleeding focus in hepatic flexure colon. Note active extravasation of contrast material into bowel lumen (arrows). C. Conventional angiography at superior mesenteric artery confirming active bleeding focus in corresponding branch artery (arrow).

CT angiography could also identify potential causes of bleeding in 45 patients (40.5%). Among them, 44 patients were confirmed to have potential bleeding causes, including ulceroinflammatory lesions (n = 29) (Fig. 3), tumors (n = 11), and diverticulosis (n = 4) in reference standard examinations. In one patient who was diagnosed with colitis on CTA, the following colonoscopy was negative. This patient did not have persistent or recurrent bleeding during the follow-up period of 11 months. In 12 patients, CTA results were regarded as false negative findings because a subsequent work-up demonstrated bleeding causes (n = 11). One patient experienced persistent bleeding after negative CTA results. In the former 11 patients, CTA could not demonstrate ulceroinflammatory lesions (n = 8), tumors (n = 1), or diverticulosis (n = 2). Therefore, to identify either a definite or potential cause of bleeding, the diagnostic yield of CTA was 61.3% (68 of 111). The overall sensitivity of CTA was 84.8% (67 of 79). Its specificity was 96.9% (31 of 32). The PPV was 98.5% (67 of 68). The NPV was 72.1% (31 of 43).

Fig. 3. 85-year-old male patient with massive hematochezia.

A, B. Axial arterial phase (A) and coronal portal venous phase (B) CT angiography showing potential bleeding focus at rectum. Note edematous wall thickening of segmental rectal wall (arrow). Subsequent colonoscopy revealed hyperemia on mucosal layer of rectum which was considered potential bleeding focus.

Clinical Characteristics Associated with Positive CT Yields

Univariable and multivariable logistic regression analyses revealed that positive CTA result was significantly associated with the presence of massive bleeding (p < 0.001, odds ratio = 11.506) (Table 3). Other clinical characteristics such as bleeding type, whether bleeding was recurrent or not, and the presence of comorbidities including diabetes, hypertension, and CVD were not significantly associated with positive CTA results.

Table 3. Clinical Characteristics Associated with Positive CTA Results.

| Clinical Feature | Patients | CTA Results* | Univariable | Multivariable | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Positive | Negative | OR | P | Adj. OR | P | ||

| Age (yr) | 0.545 | 0.246 | 0.762 | 0.53 | |||

| ≤60 | 43 | 25 (58.1) | 18 (41.9) | ||||

| ≥61 | 68 | 43 (63.2) | 25 (36.8) | ||||

| Sex | 0.965 | 0.942 | NA | NA | |||

| Female | 50 | 30 (60.0) | 20 (40.0) | ||||

| Male | 61 | 38 (62.3) | 23 (37.7) | ||||

| Bleeding type | 2.546 | 0.143 | 1.975 | 0.194 | |||

| Upper | 31 | 19 (61.3) | 12 (38.7) | ||||

| Lower | 80 | 49 (61.3) | 31 (38.8) | ||||

| Bleeding episode | 0.537 | 0.362 | NA | NA | |||

| Initial | 95 | 56 (58.9) | 39 (41.1) | ||||

| Recurrent | 16 | 12 (75.0) | 4 (25.0) | ||||

| Recent bleeding | 1.357 | 0.542 | NA | NA | |||

| Present | 67 | 42 (62.7) | 25 (37.3) | ||||

| Absent | 44 | 26 (59.1) | 18 (40.9) | ||||

| Massive bleeding | 9.097 | 0.007 | 11.506 | <0.001† | |||

| Present | 30 | 27 (90.0) | 3 (10.0) | ||||

| Absent | 81 | 41 (50.6) | 40 (49.4) | ||||

| Severe anemia | 1.816 | 0.284 | NA | NA | |||

| Present | 46 | 36 (78.3) | 10 (21.7) | ||||

| Absent | 65 | 32 (49.2) | 33 (50.8) | ||||

| Diabetes | 1.364 | 0.684 | NA | NA | |||

| Present | 19 | 13 (68.4) | 6 (31.6) | ||||

| Absent | 92 | 55 (59.8) | 37 (40.2) | ||||

| Hypertension | 0.322 | 0.293 | NA | NA | |||

| Present | 46 | 26 (56.5) | 20 (43.5) | ||||

| Absent | 65 | 42 (64.6) | 23 (35.4) | ||||

| CVD | 0.476 | 0.3 | NA | NA | |||

| Present | 16 | 8 (50.0) | 8 (50.0) | ||||

| Absent | 95 | 60 (63.2) | 35 (36.8) | ||||

| Vascular disease | 0.611 | 0.675 | NA | NA | |||

| Present | 54 | 32 (59.3) | 22 (40.7) | ||||

| Absent | 57 | 36 (63.2) | 21 (36.8) | ||||

*Data are numbers of patients, with percentages in parentheses, †Statistically significant variables. Adj. OR = adjusted odds ratio, CTA = CT angiography, CVD = cerebrovascular disease, NA = not available (values are not presented for factors that were not included in multivariate analyses)

DISCUSSION

Overt GI bleeding can make patients hemodynamically unstable. It requires rapid assessment. Appropriate management is a significant challenge for clinicians. Although several modalities have been suggested as the first-line examination for overt GI bleeding, each one has intrinsic limitations (15). Many might be related to the widely-varied causes and the nature of bleeding (16). Endoscopy still plays a primary role in the initial investigation of GI bleeding. However, it may be impractical in emergency departments due to its limited availability (6). Although optical colonoscopy has been generally accepted as the first-line diagnostic tool for patients with properly prepared colon, it has limited sensitivity (68%) in patients with an unprepared colon or with active bleeding (1, 17). Upper GI endoscopy is only able to evaluate as far down as 60 cm past the ligament of Treitz. Capsule endoscopy is not only time-consuming, but also inaccurate in localizing a bleeding focus due to its poor resolution (18). Labeled red blood cell scintigraphy can identify an intermittent bleeding focus. However, it has limited sensitivity (less than 50%) and poor resolution (19). Conventional angiography can identify active bleeding. It can be used to perform interventional procedures such as embolization. However, it is an invasive and time-consuming procedure, with mean detection rate of about 50%, which is not satisfactory (12, 18). On the contrary, CTA is a widely available non-invasive technique that can detect active bleeding at a rate of 0.3 mL/min (9, 15).

In our study, the diagnostic performance of CTA is quite promising. Its sensitivity and PPVs in detecting bleeding focus were 84.8% and 98.5%, respectively. The result is in consistent with the pooled sensitivity of 85.2% in previous meta-analysis (13). Although multiple factors can influence the ability to visualize a definite or potential bleeding focus in CTA, the severity and nature of a bleeding lesion, such as the bleeding rate or intermittence, are known to be important factors in determining CTA accuracy (13). Thus, the high diagnostic performance of CTA in our study might be related to our study sample. In one patient with active bleeding on gastroscopy, CTA failed to visualize the active bleeding focus in our study. This may be due to the intermittent nature of GI bleeding or other intrinsic factors such as hemodynamic status (11). Although CTA could demonstrate bleeding focus not detected on endoscopy or angiography (20), we should also keep in mind the possible intrinsic limitations of CTA as a detection tool for active bleeding focus.

We could not identify potential bleeding foci in 11 patients, although their bleeding foci were identified in subsequent studies. Most commonly neglected potential bleeding foci on CTA were ulceroinflammatory lesions (72.7%, 8 of 11), including gastritis (n = 3), duodenal ulcers (n = 2), or colitis (n = 3). In addition, sigmoid colon cancer (n = 1) and diverticulosis (n = 2) were not identified on CTA. One patient suffered from persistent bleeding after negative CTA and further work-up results. Therefore, our results indicate that negative CTA results do not necessarily exclude the presence of a potential bleeding focus in patients with overt GI bleeding. The need for additional diagnostic modalities such as endoscopy should be considered when CTA results are negative.

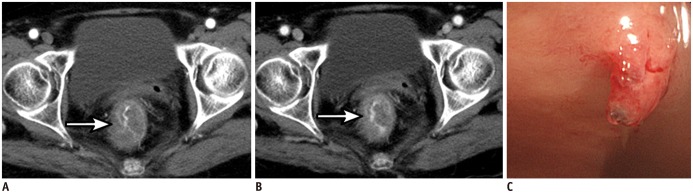

Our study indicated that clinical features might be used to select patients for whom CTA could not effectively detect the source of bleeding. Moderate-to-severe anemia was significantly associated with the presence of a definite bleeding focus on CTA in our study. Seventeen (73.9%) of 23 patients with a definite bleeding focus identified on CTA had moderate-to-severe anemia. Considering that these levels of anemia in patients with GI bleeding are associated with poor outcomes, including death and acute medical conditions prolonging their hospital stay (21), CTA might play an important role in such patients. For a definite or potential bleeding focus, the presence of massive bleeding was significantly associated (Fig. 4). Twenty-seven (39.7%) of 68 patients with a definite or potential bleeding focus identified on CTA had a history of massive bleeding. This finding is correlated with previously reported result of the usefulness of CT enterography in detecting obscure GI bleeding (10). Although the administration of neutral or negative oral contrast material may improve the diagnostic performance of CT in detecting bleeding focus (22), our CTA protocol did not include it because in an emergency setting, it may potentially cause delay in patient care. In addition, it may not be tolerated in patients with acute symptoms.

Fig. 4. 70-year-old female patient with massive hematochezia.

A, B. Axial arterial phase (A) and portal venous phase (B) CT angiography showing definite bleeding focus in rectum. Note active extravasation of contrast material into bowel lumen (arrows). C. Subsequent colonoscopy revealing Dieulafoy lesion in rectum with active bleeding.

Our study has several limitations. First, the total number of patients included in the study was relatively small. In addition, the study was conducted in a single center. Its retrospective study design limited us to investigate a true control group as well. Second, among 254 adult patients with overt GI bleeding who visited the emergency department of our hospital, only 111 patients who underwent triple phase CTA as a first-line diagnostic modality were included in this study. This could result in selection bias which might have inflated the diagnostic accuracy of CTA. In fact, while other characteristics were not significantly different between included patients and excluded patients, significantly more patients with upper GI bleeding in the excluded group were found compared to the number in the included group (Table 1). This may be because endoscopic examination is generally regarded as a first-line diagnostic modality for patients with upper GI bleeding. The first-line diagnostic modality for lower GI bleeding is still controversial (4, 5). Although this difference of bleeding location could result in selection bias, we believe that this situation can reflect the real clinical situation (23). As CTA was performed in patients without known bleeding focus, our results could reflect the performance of CTA as a first-line diagnostic modality to detect GI bleeding foci. Third, the reference standard was not uniformly obtained with all included patients. Because clinicians will choose which diagnostic modalities to be performed after CTA by considering a variety of clinical settings, we cannot obtain uniformity in future studies or clinical follow-up. Since we performed subsequent diagnostic studies after CTA in included patients, verification bias might have been introduced. In addition, the standards of reference used in our study might not be sufficient enough to evaluate bleeding foci in the small bowel. These limitations might result in an inflation of the diagnostic performance of CTA.

In conclusion, CTA as a first-line diagnostic modality in patients presenting with overt GI bleeding showed a fairly high accuracy. It could identify definite or potential bleeding focus with a moderate diagnostic yield and a high PPV. CTA is particularly useful for patients with massive bleeding.

References

- 1.Zuckerman GR, Prakash C, Askin MP, Lewis BS. AGA technical review on the evaluation and management of occult and obscure gastrointestinal bleeding. Gastroenterology. 2000;118:201–221. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(00)70430-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barnert J, Messmann H. Diagnosis and management of lower gastrointestinal bleeding. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;6:637–646. doi: 10.1038/nrgastro.2009.167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kennedy DW, Laing CJ, Tseng LH, Rosenblum DI, Tamarkin SW. Detection of active gastrointestinal hemorrhage with CT angiography: a 4(1/2)-year retrospective review. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2010;21:848–855. doi: 10.1016/j.jvir.2010.01.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.van Leerdam ME, Vreeburg EM, Rauws EA, Geraedts AA, Tijssen JG, Reitsma JB, et al. Acute upper GI bleeding: did anything change? Time trend analysis of incidence and outcome of acute upper GI bleeding between 1993/1994 and 2000. Am J Gastroenterol. 2003;98:1494–1499. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2003.07517.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Strate LL, Naumann CR. The role of colonoscopy and radiological procedures in the management of acute lower intestinal bleeding. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010;8:333–343. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2009.12.017. quiz e44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Frattaroli FM, Casciani E, Spoletini D, Polettini E, Nunziale A, Bertini L, et al. Prospective study comparing multi-detector row CT and endoscopy in acute gastrointestinal bleeding. World J Surg. 2009;33:2209–2217. doi: 10.1007/s00268-009-0156-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jensen DM, Machicado GA, Jutabha R, Kovacs TO. Urgent colonoscopy for the diagnosis and treatment of severe diverticular hemorrhage. N Engl J Med. 2000;342:78–82. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200001133420202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Whelan CT, Chen C, Kaboli P, Siddique J, Prochaska M, Meltzer DO. Upper versus lower gastrointestinal bleeding: a direct comparison of clinical presentation, outcomes, and resource utilization. J Hosp Med. 2010;5:141–147. doi: 10.1002/jhm.606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Martí M, Artigas JM, Garzón G, Alvarez-Sala R, Soto JA. Acute lower intestinal bleeding: feasibility and diagnostic performance of CT angiography. Radiology. 2012;262:109–116. doi: 10.1148/radiol.11110326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lee SS, Oh TS, Kim HJ, Chung JW, Park SH, Kim AY, et al. Obscure gastrointestinal bleeding: diagnostic performance of multidetector CT enterography. Radiology. 2011;259:739–748. doi: 10.1148/radiol.11101936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jaeckle T, Stuber G, Hoffmann MH, Jeltsch M, Schmitz BL, Aschoff AJ. Detection and localization of acute upper and lower gastrointestinal (GI) bleeding with arterial phase multidetector row helical CT. Eur Radiol. 2008;18:1406–1413. doi: 10.1007/s00330-008-0907-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yoon W, Jeong YY, Shin SS, Lim HS, Song SG, Jang NG, et al. Acute massive gastrointestinal bleeding: detection and localization with arterial phase multi-detector row helical CT. Radiology. 2006;239:160–167. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2383050175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.García-Blázquez V, Vicente-Bártulos A, Olavarria-Delgado A, Plana MN, van der Winden D, Zamora J, et al. Accuracy of CT angiography in the diagnosis of acute gastrointestinal bleeding: systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur Radiol. 2013;23:1181–1190. doi: 10.1007/s00330-012-2721-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pennazio M, Santucci R, Rondonotti E, Abbiati C, Beccari G, Rossini FP, et al. Outcome of patients with obscure gastrointestinal bleeding after capsule endoscopy: report of 100 consecutive cases. Gastroenterology. 2004;126:643–653. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2003.11.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Geffroy Y, Rodallec MH, Boulay-Coletta I, Jullès MC, Ridereau-Zins C, Zins M. Multidetector CT angiography in acute gastrointestinal bleeding: why, when, and how. Radiographics. 2011;31:E35–E46. doi: 10.1148/rg.313105206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lefkovitz Z, Cappell MS, Kaplan M, Mitty H, Gerard P. Radiology in the diagnosis and therapy of gastrointestinal bleeding. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2000;29:489–512. doi: 10.1016/s0889-8553(05)70124-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ernst O, Bulois P, Saint-Drenant S, Leroy C, Paris JC, Sergent G. Helical CT in acute lower gastrointestinal bleeding. Eur Radiol. 2003;13:114–117. doi: 10.1007/s00330-002-1442-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yoon W, Jeong YY, Kim JK. Acute gastrointestinal bleeding: contrast-enhanced MDCT. Abdom Imaging. 2006;31:1–8. doi: 10.1007/s00261-005-0367-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Duchesne J, Jacome T, Serou M, Tighe D, Gonzales A, Hunt JP, et al. CT-angiography for the detection of a lower gastrointestinal bleeding source. Am Surg. 2005;71:392–397. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Miller FH, Hwang CM. An initial experience: using helical CT imaging to detect obscure gastrointestinal bleeding. Clin Imaging. 2004;28:245–251. doi: 10.1016/S0899-7071(03)00193-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Velayos FS, Williamson A, Sousa KH, Lung E, Bostrom A, Weber EJ, et al. Early predictors of severe lower gastrointestinal bleeding and adverse outcomes: a prospective study. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2004;2:485–490. doi: 10.1016/s1542-3565(04)00167-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Stuhlfaut JW, Soto JA, Lucey BC, Ulrich A, Rathlev NK, Burke PA, et al. Blunt abdominal trauma: performance of CT without oral contrast material. Radiology. 2004;233:689–694. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2333031972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Khamaysi I, Gralnek IM. Acute upper gastrointestinal bleeding (UGIB) - initial evaluation and management. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2013;27:633–638. doi: 10.1016/j.bpg.2013.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]