Abstract

Background

In the fetus with hypoplastic left heart syndrome (HLHS), the single right ventricle (RV) pumps the entire cardiac output in utero. By investigating RV performance in utero, we sought to determine the inherent capabilities of a single RV prior to the increased metabolic demands of postnatal life and surgical palliation. In addition, we sought to determine whether the presence or absence of a left ventricular (LV) cavity impacts upon RV performance in fetal life.

Methods

Between November 2004 and December 2006, Doppler flow-derived measures of ventricular performance were obtained via echocardiography in 76 fetuses with normal cardiovascular system and in 48 age-matched fetuses with HLHS from 17 weeks until 40 weeks gestation. The myocardial performance index, ventricular ejection force, and cardiac output were determined for both groups and compared via unpaired t-tests and regression analysis.

Results

In fetuses with HLHS, cardiac output was diminished by 20%, RV ejection force elevated, and RV myocardial performance index elevated compared to normal fetuses. The presence of an LV cavity did not impact upon RV performance in utero.

Conclusions

Fetuses with HLHS have preserved systolic performance but impaired diastolic performance compared to normal fetuses. The heart of a fetus with HLHS is less efficient than the normal heart in that ejection force of the RV is increased, but overall delivery of cardiac output is lower than normal. We conclude that patients with HLHS have inherent limitations in cardiac performance even prior to birth.

Keywords: Fetus, Hypoplastic Left Heart Syndrome, Right Ventricular Performance

Introduction

In the hypoplastic left heart syndrome (HLHS), inadequacy of the left-sided structures shifts the role of circulatory perfusion solely onto the right ventricle (RV). With the task of circulatory perfusion thrust upon it, RV performance is critical to well-being both before and after birth. Despite the presence of only one effective ventricular chamber, circulatory perfusion in the fetus with HLHS is believed to be sufficient for in-utero demands, as fetal growth takes place and hydrops fetalis, heart failure, or intrauterine fetal demise is extremely rare in the absence of severe tricuspid regurgitation. After birth and through staged palliative reconstruction, new demands are imposed upon the RV. Relative to fetal life, metabolic demands of the newborn and child are increased. After birth, the RV must provide for both the systemic and pulmonary circulations for the first few months of life, and function long-term as the systemic ventricle thereafter. Thus far, data suggests that the RV performs satisfactorily as the systemic ventricle in most patients with HLHS[1–2]; however, in some, RV failure can occur in childhood and questions remain as to the potential viability of the RV for long-term performance into adulthood.

Studying RV performance in the fetus with HLHS may offer unique insights into our understanding of this anomaly. The natural “untouched” heart of the fetus with HLHS has not yet been exposed to the physiological loads imposed by the postnatal circulation, the insults of open heart surgery, or the chronic volume loads of a stage 1 Norwood circulation. Therefore studying the RV in the fetus with HLHS may provide a fundamental understanding of the inherent capacities of the heart in this anomaly. In addition, recent findings suggest that neurocognitive deficits experienced by survivors of reconstructive surgery for HLHS may in part be due to abnormalities of fetal central nervous system development or alterations in fetal cerebral blood flow patterns[3–5]. These abnormalities may be related to impaired cerebrovascular perfusion as a consequence of deficiency in RV performance.

In this study, we use the fetal echocardiography Doppler-derived measures of myocardial performance index[6–7], ventricular ejection force[8], and indexed cardiac output[9–10] to assess RV performance in the fetus with HLHS. In addition, we look at the potential impact of the presence of a non-contributory, left ventricle (LV) cavity on RV performance.

Patients and Methods

A cross-sectional, retrospective study was undertaken with institutional review board approval. A waiver for consent was obtained from the institutional review board. The study population consisted of pregnant women referred for fetal echocardiography to the Fetal Heart Program at the Cardiac Center at The Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia from November 2004 to December 2006. Inclusion criteria for analysis were fetuses with: 1) normal cardiovascular anatomy, normal uteroplacental function, and no extra-cardiac anatomic abnormalities of hemodynamic significance (normal controls), and 2) HLHS, defined as mitral atresia or severe stenosis, and aortic atresia or severe stenosis, with left ventricular hypoplasia. All fetuses with HLHS had left-to-right shunting at the atrial level and reversal of flow in the transverse portion of the aortic arch as a consequence of retrograde perfusion via the ductus arteriosus. When an LV cavity was present, there was no significant ejection noted. Exclusion criteria were gestational age less than 16 weeks or greater than 42 weeks, persistent non-sinus rhythm, or any maternal condition which might affect fetal hemodynamics, such as gestational diabetes, thyroid disease or pre-eclampsia. All fetuses had the qualitative appearance of normal ventricular function on two-dimensional imaging and no fetus had more than mild tricuspid regurgitation on color Doppler imaging. Normal fetuses were evaluated only once. HLHS fetuses were evaluated serially over the course of gestation. For the purposes of this cross-sectional study, only the first evaluation was included in the analysis.

Ultrasound Evaluation

A complete fetal echocardiogram was performed using a Siemens ACUSON Sequoia 256 system (Mountainview, CA) coupled with a 6C2 transducer. Gestational age varied from 17 weeks to 40 weeks. Pregnancy duration was estimated from the last menstrual period and confirmed by ultrasound measurement. Multiple two dimensional views of the heart were obtained to evaluate fetal cardiac anatomy, as previously described[11]. All images were recorded digitally as clips or still-frames and stored on our digital archiving system (Siemens KinetDx, Mountainview, CA). Pulsed Doppler signals were obtained at the tips of the tricuspid and mitral valves from an apical four-chamber view in diastole, and at the annuli of the pulmonic or aortic valves in the outflow tract views in systole for normal fetuses[11]. In HLHS fetuses, pulsed Doppler signals were obtained only at the tips of the tricuspid valve from the apical view in diastole, and at the annulus of the pulmonic valve in the outflow tract in systole. All Doppler recordings were obtained at an insonation angle <10 degrees to flow. Angle correction was not used. Measurements of the pulmonic and aortic annuli for normal fetuses and measurements of the pulmonic annulus for HLHS fetuses were made in systole at right angles to the plane of flow[11].

Doppler-Derived Flow Parameters

Measurements were performed using the KinetDx (Siemens, Mountain View, CA) cardiovascular imaging software. The myocardial performance (MPI) index of Tei is a global measure of combined systolic and diastolic performance and is defined as the sum of the isovolumic contraction time and the isovolumic relaxation time (isovolumetric time) divided by the ejection time[6–7]. The isovolumetric time is obtained by subtracting the aortic or pulmonic ejection time from the period between the cessation and the onset of either the mitral or tricuspid inflow signal. A higher MPI value corresponds to a greater degree of ventricular dysfunction. The ventricular ejection force is calculated according to Isaaz’s formula, previously described [8]. Ventricular ejection force = (1.055 × the cross-sectional area of the valve × the velocity time integral during the acceleration phase) × (the peak systolic velocity of the Doppler envelope/time to peak velocity), where 1.055 represents the density of blood. The formula describes the acceleration of blood across the pulmonic or aortic valve over a specific time interval (onset of flow to peak velocity), and is a reflection of systolic ventricular performance derived from Newton’s laws. A higher value corresponds to greater force exerted in ejecting the ventricular volume of blood during systole. Finally, the combined cardiac output (CCO) was determined by summing the right and left cardiac outputs, individually calculated according to the formula: cardiac output = valve cross sectional area × heart rate × time velocity integral across the valve in systole[9–10]. CCO values were indexed to the estimated weight in kilograms[12–13]. In HLHS fetuses, the left ventricular cardiac output was assumed to be negligible, as there was retrograde flow in the aortic arch. Therefore, only right ventricular cardiac output (RVCO) was determined. For all Doppler-derived measurements, at least three uniform signals were measured and the results averaged for analysis.

Statistical Analysis

The fetal gestational age, MPI, and indexed cardiac output were found to be normally distributed for both normal and HLHS fetuses while ejection force and estimated fetal weight were not normally distributed. Similar to the findings of previous investigators, we found no significant change in the RV MPI[14–16] (R2 for HLHS < 0.01 and R2 for normal control < 0.01) or indexed CCO[13] (R2 for HLHS =0.04 and R2 for normal control <0.01) for either group over the course of gestation. Consequently, these data were expressed as the mean +/− standard deviation and unpaired student’s t-tests were used for comparison of means. In contrast, right ventricular ejection force increased significantly over the course of gestation. Polynomial regression analysis was performed using Intercooled Stata 9 (StataCorp, College Station, TX) to demonstrate the relationship between right ventricular ejection force and gestational age. In order to test the hypothesis that the HLHS RV ejection force differed significantly from the normal control RV ejection force, a univariate generalized linear model was constructed using SPSS version 15 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL). Because variance in ejection force measurements increased significantly with advancing gestational age, a log(10) transformation of the ejection force data was performed in order to stabilize variance. In the univariate linear model, gestational age was the predictor variable and log(10) RV ejection force was the dependent variable. Estimated marginal means for each group were generated based upon the linear model and pair-wise comparisons made to determine significance. Finally, the Mann Whitney U test was used to test for differences in estimated fetal weight and the untransformed RVEF. All values were considered significantly different at a p < 0.05.

In order to test the hypothesis that the presence of a left ventricle (LV) cavity impacts upon parameters of RV performance in fetuses with HLHS, subgroup analysis was performed. Fetuses were stratified into absent LV cavity if there was an absent or severely hypoplastic LV with mitral atresia and no ventricular septal defect. Fetuses were stratified into present LV cavity if there was a left ventricle present with either mitral stenosis or mitral atresia with a ventricular septal defect. Right ventricular myocardial performance indices and right ventricular cardiac outputs were compared between the two groups via 2-tailed student’s t-tests. As described above, a univariate generalized linear model using log(10) transformed right ventricular ejection forces was used to compare the estimated marginal means of the right ventricular ejection forces between the two subgroups.

Results

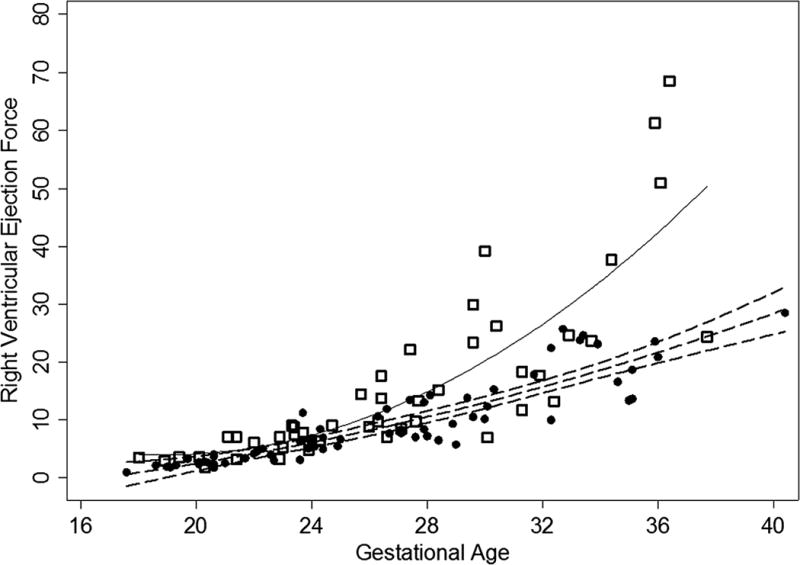

The study population consisted of 76 normal fetuses and 48 fetuses with HLHS. As shown in Table 1, there was no significant difference in gestational age between these two study groups. Fetuses with HLHS have significantly elevated right ventricular myocardial performance indices compared to normal control fetuses and significantly lower cardiac outputs. Figure 1 and Table 2 demonstrate that HLHS fetuses have significantly higher right ventricular ejection forces compared to normal control fetuses. The polynomial regression curves diverge in the late second trimester and are markedly different at term.

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics and Doppler-derived Measures of Ventricular Performance for the Study Groups. GA, MPI, and CO are expressed as mean +/− standard deviation. Fetal weight and RV or LV Ejection Force are expressed as median (range).

| Variable | HLHS (n=48) | Normal (n=76) | p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| GA (wks) | 26.7 +/− 5.2 | 25.9 +/− 5.2 | 0.41 |

| Fetal weight (kg) | 0.89 (0.31–3.26) | 0.82 (0.20–3.84) | 0.63 |

| RV MPI | 0.47 +/− 0.07 | 0.43 +/− 0.05 | 0.002 |

| LV MPI | – | 0.40 +/− 0.05 | – |

| RV Ejection Force (mN) | 9.03 (1.86–68.5) | 6.62 (0.97–28.5) | 0.002 |

| LV Ejection Force (mN) | – | 5.82 (0.73–24.2) | – |

| RVCO or CCO (cc/min/kg) | 382 +/− 77 | 477 +/− 79 | <0.001 |

Figure 1.

Right ventricular ejection force vs. gestational age for HLHS population (open squares) and normal control population (circles). The quadratic regression line for the normal control population is the dashed line, RVEF = 0.03 (GA)2 −0.25 (GA) −2.9, R2 = 0.82 while the quadratic regression line for the HLHS population is the solid line, RVEF = 0.13 (GA)2 −4.95(GA) + 50.6, R2 = 0.68. The 95% confidence intervals are also illustrated for the normal control population (dashed lines).

Table 2.

Univariate linear model predicting log(10) transformed RVEF based upon gestational age (GA) with the coefficient of beta adjusted for the effect of the group. In the model, all parameter estimates were statistically significant, p<0.001. The R2 of the model was 0.83, p<0.001. The between group effect was also statistically significant, F=36.5, p<0.001. Consequently, estimated marginal means were calculated according to the univariate linear model at 26.2 weeks gestation.

| Parameter | ParameterEstimate | Standard Error | Estimated marginal mean at 26.1 weeks |

|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | −0.64 | 0.08 | |

| GA | 0.06 | <0.01 | |

| Normal control RVEF | −0.18 | 0.03 | 0.83* |

| HLHS RVEF | 0a | 0a | 1.00* |

The difference between the estimated marginal means was significant, p<0.001.

This parameter is set to zero because it is redundant within the equation.

In the subgroup analysis of fetuses with HLHS, 23 had no LV cavity and 25 had an LV cavity. Table 3 summarizes the subgroup analysis for HLHS fetuses with and without an LV cavity. Fetuses without an LV cavity were slightly older in gestation than fetuses with an LV cavity, although the difference was not statistically significant. There were no statistically significant differences in RV MPI, RVCO, estimated fetal weight, and estimated marginal means of the log (10) transformed RV ejection forces.

Table 3.

Subgroup Analysis of HLHS fetuses with and without an LV cavity. GA, MPI, log(10) RVEF and CO are expressed as mean +/− standard deviation. Fetal weight is expressed as median (range). Estimated marginal means are calculated at 26.8weeks gestation according to the equation 0.063 (GA) −0.66 + 0.038 (if no LV present), R2 = 0.78.

| Variable | No LV (23) | LV present (25) | p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| GA (wks) | 27.5 +/− 4.9 | 25.8 +/− 5.3 | 0.26 |

| Fetal weight (kg) | 0.96 (0.30 – 2.88) | 0.72 (0.31− 3.26) | 0.23 |

| RV MPI | 0.47 +/− 0.07 | 0.47 +/− 0.07 | 0.80 |

| Log 10 (RVEF) (mN) at 26.8 weeks gestation | 1.06 +/− 0.04 | 1.02 +/− 0.04 | 0.47 |

| RVCO (cc/min/kg) | 397 +/− 75 | 367 +/− 77 | 0.21 |

Comment

Our study reveals the presence of important differences in ventricular performance between the normal fetus and the fetus with HLHS. First, RV MPI is elevated in fetuses with HLHS compared to normal. The myocardial performance index reflects both systolic and diastolic elements of performance[7]. Systolic performance was well preserved in all fetuses with HLHS based on qualitative imaging and as demonstrated by elevated RV ejection force. It is conceivable that as the single RV matures in HLHS, it hypertrophies to generate the entire cardiac output, hence the compliance of the ventricle decreases, thereby leading to impairment in diastolic relaxation. Diastolic dysfunction, as evidenced by an elevated MPI, has been identified in the systemic right ventricle of children with HLHS after Fontan operation[17]. Our findings suggest that diastolic dysfunction occurs before birth in fetuses with HLHS and may be a phenomenon which accompanies these children as they go through the various stages of surgical reconstruction. In the future, we may be able to mitigate the effects of diastolic dysfunction in utero by prescribing medications deemed safe in pregnancy to improve fetal RV compliance. The impact of therapy could then be assessed with serial assessments of the MPI over the course of gestation.

Second, as previously reported by Rasanen et al.[18], our findings demonstrate that the RV ejection force in fetuses with HLHS is consistently higher than the RV ejection force of normal fetuses of a similar mean gestational age. Previous investigators have demonstrated the ability of the fetal myocardium to undergo myocyte proliferation in response to increased preload or afterload[19–21]. As the RV myocytes proliferate and the cavity dilates to accommodate the increased preload delivered to the single RV, a greater force may be generated with each ventricular contraction. Doppler studies performed in adults have demonstrated a close correlation between the left ventricular ejection force and left ventricular ejection fraction, a reliable measure of systolic performance[8]. Consequently, healthy fetuses with HLHS have normal or even hyperdynamic right ventricular systolic function compared to normal control fetuses of a similar gestational age.

Third, in spite of normal or perhaps even hyperdynamic systolic RV function, our data shows that the indexed cardiac output generated by fetuses with HLHS is approximately 20% lower than normal fetuses of a similar gestational age. Despite ventricular enlargement and hypertrophy, the single RV does not generate a normal cardiac output in the fetus with HLHS. The findings of a lower cardiac output may explain, in part, the lower weight seen in fetuses with HLHS at birth and the higher prevalence of microcephaly in this population[22]. A growing body of literature has identified the presence of structural central nervous system abnormalities and functional neurocognitive deficits in infants and children with HLHS[23–26]. Two recent studies strongly suggest the presence of these abnormalities prior to birth[4, 27]. Low cardiac output during fetal life in the presence of a structurally normal heart has been cited as a cause for poor neurodevelopmental outcome in conditions of placental insufficiency[28]. Low cardiac output with impaired cerebrovascular perfusion in-utero may explain the development of these central nervous system abnormalities in our patients with HLHS. Substantial differences in cerebrovascular resistance of fetuses with HLHS in comparison to normal as measured by Doppler blood flow in the middle cerebral artery have been described[3–5], however correlation between these abnormalities and functional neurocognitive outcome has not yet been investigated.

Finally, subgroup analysis in our HLHS population did not reveal any statistically significant differences in ventricular performance between fetuses with and without an LV cavity. We hypothesized that fetuses with a hypertrophied, dysfunctional left ventricular cavity may have an adverse left ventricle-to-right ventricle interaction which negatively impacts right ventricular performance. Negative ventriculo-ventricular interactions have been described in patients with HLHS after reconstructive surgery[29]. In a series of 48 pediatric HLHS patients who had survived the Fontan operation, Wisler et al. recently reported a negative effect of LV size upon RV performance only prior to the Fontan operation[30]. No effect of LV size upon RV performance was noted before the Norwood procedure, before the Glenn procedure, or after the Fontan procedure[30]. Our findings suggest that negative interactions of a non-contributory LV cavity upon RV performance are negligible in the fetus. These interactions may theoretically become apparent after birth in the presence of new demands and loading conditions that are imposed upon the RV.

In summary, our study demonstrates that fetuses with HLHS have preserved, or even hyperdynamic, systolic performance but impaired diastolic performance compared to normal fetuses. Most importantly, indexed cardiac output is diminished by approximately 20% in the fetus with HLHS. The combined application of these Doppler derived indices teaches us that the heart of a fetus with HLHS is less efficient than the normal heart in that ejection force of the RV is increased, but overall delivery of cardiac output is lower than normal. In essence, the single RV in the fetus cannot make up for the absence of the left ventricle. Further investigations looking at the relationship between parameters of right ventricular performance and outcomes are warranted. These findings have important fundamental implications for managing the fetus with HLHS, as maneuvers aimed towards optimizing cardiac output during gestation as well as during the perinatal period prior to surgical intervention may influence outcomes for these infants. It is conceivable that medications will someday be prescribed to mothers carrying fetuses with HLHS in order to maximize cardiac output in utero. Serial assessment of these parameters of ventricular performance could then assess the impact of therapy in utero.

Acknowledgments

AL Szwast was partially funded for this work by the National Institutes of Health, Rockville, MD: NIH training grant T32-HL007915.

Abbreviations and Acronyms

- HLHS

hypoplastic left heart syndrome

- RV

right ventricle

- LV

left ventricle

- MPI

myocardial performance index

- RVCO

right ventricular cardiac output

- CCO

combined cardiac output

References

- 1.Hirsch JC, Ohye RG, Devaney EJ, Goldberg CS, Bove EL. The lateral tunnel fontan procedure for hypoplastic left heart syndrome: results of 100 consecutive patients. Pediatr Cardiol. 2007;28:426–32. doi: 10.1007/s00246-007-9002-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mitchell ME, Ittenbach RF, Gaynor JW, et al. Intermediate outcomes after the Fontan procedure in the current era. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2006;131:172–80. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2005.08.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kaltman JR, Di H, Tian Z, Rychik J. Impact of congenital heart disease on cerebrovascular blood flow dynamics in the fetus. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2005;25:32–6. doi: 10.1002/uog.1785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Miller SP, McQuillen PS, Hamrick S, et al. Abnormal brain development in newborns with congenital heart disease. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:1928–38. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa067393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Donofrio MT, Bremer YA, Schieken RM, et al. Autoregulation of cerebral blood flow in fetuses with congenital heart disease: the brain sparing effect. Pediatr Cardiol. 2003;24:436–43. doi: 10.1007/s00246-002-0404-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tei C, Nishimura RA, Seward JB, Tajik AJ. Noninvasive Doppler-derived myocardial performance index: correlation with simultaneous measurements of cardiac catheterization measurements. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 1997;10:169–78. doi: 10.1016/s0894-7317(97)70090-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tei C, Ling LH, Hodge DO, et al. New index of combined systolic and diastolic myocardial performance: a simple and reproducible measure of cardiac function–a study in normals and dilated cardiomyopathy. J Cardiol. 1995;26:357–66. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Isaaz K, Ethevenot G, Admant P, Brembilla B, Pernot C. A new Doppler method of assessing left ventricular ejection force in chronic congestive heart failure. Am J Cardiol. 1989;64:81–7. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(89)90657-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Huntsman LL, Stewart DK, Barnes SR, et al. Noninvasive Doppler determination of cardiac output in man. Clinical validation Circulation. 1983;67:593–602. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.67.3.593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dubin J, Wallerson DC, Cody RJ, Devereux RB. Comparative accuracy of Doppler echocardiographic methods for clinical stroke volume determination. Am Heart J. 1990;120:116–23. doi: 10.1016/0002-8703(90)90168-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rychik J, Ayres N, Cuneo B, et al. American Society of Echocardiography guidelines and standards for performance of the fetal echocardiogram. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2004;17:803–10. doi: 10.1016/j.echo.2004.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mielke G, Benda N. Cardiac output and central distribution of blood flow in the human fetus. Circulation. 2001;103:1662–8. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.103.12.1662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.De Smedt MC, Visser GH, Meijboom EJ. Fetal cardiac output estimated by Doppler echocardiography during mid- and late gestation. Am J Cardiol. 1987;60:338–42. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(87)90238-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Eidem BW, Edwards JM, Cetta F. Quantitative assessment of fetal ventricular function: establishing normal values of the myocardial performance index in the fetus. Echocardiography. 2001;18:9–13. doi: 10.1046/j.1540-8175.2001.t01-1-00009.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Friedman D, Buyon J, Kim M, Glickstein JS. Fetal cardiac function assessed by Doppler myocardial performance index (Tei Index) Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2003;21:33–6. doi: 10.1002/uog.11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Falkensammer CB, Paul J, Huhta JC. Fetal congestive heart failure: correlation of Tei-index and Cardiovascular-score. J Perinat Med. 2001;29:390–8. doi: 10.1515/JPM.2001.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mahle WT, Coon PD, Wernovsky G, Rychik J. Quantitative echocardiographic assessment of the performance of the functionally single right ventricle after the Fontan operation. Cardiol Young. 2001;11:399–406. doi: 10.1017/s1047951101000518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rasanen J, Debbs RH, Wood DC, et al. Human fetal right ventricular ejection force under abnormal loading conditions during the second half of pregnancy. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 1997;10:325–32. doi: 10.1046/j.1469-0705.1997.10050325.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pinson CW, Morton MJ, Thornburg KL. Mild pressure loading alters right ventricular function in fetal sheep. Circ Res. 1991;68:947–57. doi: 10.1161/01.res.68.4.947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.DeAlmeida A, McQuinn T, Sedmera D. Increased ventricular preload is compensated by myocyte proliferation in normal and hypoplastic fetal chick left ventricle. Circ Res. 2007;100:1363–70. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000266606.88463.cb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fishman NH, Hof RB, Rudolph AM, Heymann MA. Models of congenital heart disease in fetal lambs. Circulation. 1978;58:354–64. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.58.2.354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rosenthal GL. Patterns of prenatal growth among infants with cardiovascular malformations: possible fetal hemodynamic effects. Am J Epidemiol. 1996;143:505–13. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a008771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mahle WT, Visconti KJ, Freier MC, et al. Relationship of surgical approach to neurodevelopmental outcomes in hypoplastic left heart syndrome. Pediatrics. 2006;117:e90–e97. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-0575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Goldberg CS, Schwartz EM, Brunberg JA, et al. Neurodevelopmental outcome of patients after the fontan operation: A comparison between children with hypoplastic left heart syndrome and other functional single ventricle lesions. J Pediatr. 2000;137:646–52. doi: 10.1067/mpd.2000.108952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mahle WT, Clancy RR, Moss EM, et al. Neurodevelopmental outcome and lifestyle assessment in school-aged and adolescent children with hypoplastic left heart syndrome. Pediatrics. 2000;105:1082–9. doi: 10.1542/peds.105.5.1082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kern JH, Hinton VJ, Nereo NE, Hayes CJ, Gersony WM. Early developmental outcome after the Norwood procedure for hypoplastic left heart syndrome. Pediatrics. 1998;102:1148–52. doi: 10.1542/peds.102.5.1148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dent CL, Spaeth JP, Jones BV, et al. Brain magnetic resonance imaging abnormalities after the Norwood procedure using regional cerebral perfusion. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2006;131:190–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2005.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kaukola T, Rasanen J, Herva R, Patel DD, Hallman M. Suboptimal neurodevelopment in very preterm infants is related to fetal cardiovascular compromise in placental insufficiency. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2005;193:414–20. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2004.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fogel MA, Weinberg PM, Fellows KE, Hoffman EA. A study in ventricular-ventricular interaction. Single right ventricles compared with systemic right ventricles in a dual-chamber circulation. Circulation. 1995;92:219–30. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.92.2.219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wisler J, Khoury PR, Kimball TR. The effect of left ventricular size on right ventricular hemodynamics in pediatric survivors with hypoplastic left heart syndrome. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2008;21:464–9. doi: 10.1016/j.echo.2007.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]