Abstract

Background

Given 4 million individuals in the United States suffer from atrial fibrillation, understanding the epidemiology of this disease is crucial. We sought to identify and characterize the impact of age on national atrial fibrillation hospitalization patterns.

Methods

The study sample was drawn from the 2009–2010 Nationwide Inpatient Sample (NIS). Patients hospitalized with a principal ICD9 discharge diagnosis of atrial fibrillation were included. Patients were categorized as “older” (65 and older) or “younger” (under 65 years) for the purposes of analysis. The outcomes measured included hospitalization rate, length of stay, in-hospital mortality, and discharge status.

Results

We identified 192,846 atrial fibrillation hospitalizations. There was significant geographic variation in hospitalizations for both younger and older age groups. States with high hospitalizations differed from those states known to have high stroke mortality. Younger patients (33% of the sample) were more likely to be obese (21% versus 8%, p<0.001) and use alcohol (8% versus 2%, p<0.001). Older patients were more likely to have kidney disease (14% versus 7%, p<0.001). Both age groups had high rates of hypertension and diabetes. Older patients had higher in-hospital mortality and were more likely to be discharged to a nursing or intermediate care facility.

Conclusions

Younger patients account for a substantial minority of atrial fibrillation hospitalizations in contemporary practice. Younger patients are healthier, with a different distribution of risk factors, than older patients who have higher associated morbidity and mortality.

Keywords: Atrial Fibrillation, Age, Epidemiology

Introduction

Atrial fibrillation is the most common arrhythmia in the world, with a prevalence of approximately 4 million individuals in the United States alone.1 Although often considered to be a relatively benign condition, it is a major risk factor for ischemic stroke, accounting for 15% of cases,2 and is independently associated with increased mortality.3 In addition, symptomatic atrial fibrillation can significantly affect quality of life and functional status.4 The cost of hospitalization is about three times that of individuals without atrial fibrillation, driving an incremental cost ranging from 6 to 26 billion dollars annually.5 Studies suggest atrial fibrillation is a growing epidemic, with the incidence expected to more than double in the next 50 years.4,6 Given the implications of this, the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute has made the understanding of its epidemiology a top priority.7

Much of the literature to date has made inferences based on county or regional data,6,8 which suggest that atrial fibrillation is predominantly a condition of elderly men.8 However, it is detected incidentally in 30–45% of patients.9,10 This raises the possibility that other groups of individuals may remain undiagnosed until symptoms occur. With increased awareness of the substantial stroke risk associated with atrial fibrillation, the demographic patterns previously reported in the literature may have changed. Although patients requiring admission for atrial fibrillation represent only a subset of the overall atrial fibrillation population, they are likely the population that largely drives the individual and societal burden of the disease. The demographic pattern of patients admitted for its management has not been well defined, and the influence of age on the epidemiology of the disease requires further exploration. We therefore sought to identify and characterize the impact of age on national patterns of atrial fibrillation hospitalization using data from the 2009–2010 Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP) database.

Methods

Study Population

The study sample was drawn from the Nationwide Inpatient Sample (NIS) of the HCUP database created by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ). It is the largest collection of longitudinal patient hospitalization data in the United States and includes patients regardless of insurance status. The 2009 and 2010 combined NIS dataset, which included 1051 hospitals (representing a 20 percent stratified sample of United States community hospitals) located in 46 states (representing 96 percent of the United States population), was used.11 No NIS data is available for the states of Idaho, North Dakota, Alabama, or Delaware. Analysis was conducted for all patients 15 years of age or older with a principal discharge diagnosis of atrial fibrillation based on the International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification ([ICD-9-CM] code 427.31 and 427.32) and restricted to patients discharged from an acute-care, short-term hospital.

Outcomes and patient characteristics

Outcomes included annual hospitalization rates, length of stay, major discharge disposition, and in-hospital mortality. Length of stay was defined as the date of discharge minus the date of admission plus one day. If the date of discharge was the same as the date of admission, it was counted as 1. Major discharge dispositions included discharge to home, intermediate care facility or skilled nursing facility, or hospice. In-hospital mortality was defined as all-cause death during an index atrial fibrillation hospitalization. Mortality and discharge disposition rates were expressed as a percentage and length of stay as mean (standard deviation [SD]) days. All outcomes were compared between the “younger” group (under 65 years) and the “older” group (age 65 and older). This division was made in order to compare, to the best of our ability, Medicare-eligible versus non-Medicare patients. Patient demographics and comorbidities analyzed are shown in Table 1. Pertinent comorbidities were defined by the AHRQ definitions and then extracted from the HCUP datasets (http://www.hcupus.ahrq.gov/toolssoftware/comorbidity/comorbidity.jsp).

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics of Younger versus Older Patients

| Characteristic | Age <65 years (N=62,868) no. (%) | Age ≥65 years (N=129,978) no. (%) | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (yr) | |||

| Mean Age (Interquartile Range) | 54 (49–61) | 78 (71–84) | |

| Triage Setting | |||

| Admission from ER- no. (%) | 43,406 (69) | 91,069 (70) | <0.001 |

| Transferred* | 3,129 (5) | 7,877 (6) | <0.001 |

| Female | 20,770 (33) | 76,307 (59) | <0.001 |

| Comorbidities | |||

| COPD | 10761 (6) | 30110 (23) | <0.001 |

| Hyperthyroidism | 862 (1.37) | 1,074 (0.83) | <0.001 |

| Heart Failure | 155 (0.25) | 640 (0.5) | <0.001 |

| Depression | 4892 (8) | 9639 (7) | 0.004 |

| Diabetes | 14,521 (23) | 32,736 (69) | <0.001 |

| HTN | 35,745 (57) | 90,813 (70) | <0.001 |

| Liver Disease | 1,477 (2.4) | 1,197 (0.92) | <0.001 |

| Metastatic Cancer | 590 (0.94) | 2,171 (1.67) | <0.001 |

| Peripheral Vascular Disease | 1,876 (3) | 10,523 (8) | <0.001 |

| Renal Failure | 4,486 (7) | 18,076 (14) | <0.001 |

| Obesity | 13,349 (21) | 10,856 (8) | <0.001 |

| CAD | 536 (.85) | 2.480 (1.9) | <0.001 |

| Alcohol Use | 5,206 (8) | 2,404 (2) | <0.001 |

| Illicit Drug Use | 1,945 (3) | 303 (0.2) | <0.001 |

| Valvular Heart Disease | 57 (0.09) | 287 (0.2) | <0.001 |

| Weight Loss | 508 (.8) | 3,101 (2.4) | <0.001 |

| Stroke | 442 (0.7) | 3,130 (2.4) | <0.001 |

COPD= Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease, CAD= Coronary Artery Disease

Refers to transfers received from other facilities

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive and bivariate analyses were conducted to evaluate gender differences in patient characteristics and outcomes. The Chi-square test was used to compare dichotomous and categorical variables, and the t-test was used to compare continuous variables. We divided hospitalizations into 5-year incremental age-clusters by gender and state and linked the age-sex-state data to the 2009 and 2010 U.S. Census gender-age-sex-state specific estimated population to calculate the annual atrial fibrillation hospitalization rate (per 100,000 person-years). To evaluate atrial fibrillation hospitalizations across states, we fitted a generalized linear mixed model with a Poisson link function and state-specific random intercepts, with the above linked hospitalization data, to calculate an age-sex-adjusted state-specific hospitalization rate for the “younger” and the “older” age groups within each of the 46 states. We used the nonparametric bootstrap method to generate 3,000 samples with replacement to obtain the 95% confidence interval (CI) for the state-specific rate, which was used to classify each state into three groups based on its 95% CI: 1) Significantly lower than the national average, 2) Significantly higher than the national average, and 3) Same as the national average.

Using the bootstrapping samples, we calculated a difference in atrial fibrillation hospitalization rates between the “young” and “older” groups and the 95% CI of the difference. We then classified each state into one of the above three groups. This approach has been used elsewhere.12,13 Hospitalization analyses was weighted by a sampling weight included in the HCUP data. All statistical testing was 2-sided, at a significance level of 0.05, and all analyses were conducted using SAS 64-bit version 9.3 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC). Institutional Review Board approval was obtained through the Brigham and Women’s Hospital Human Investigation Committee.

Results

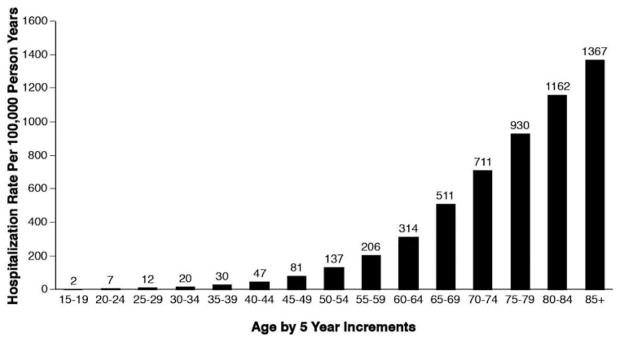

The study sample included a total of 192,846 hospitalizations (50% female) with atrial fibrillation as the primary discharge diagnosis across 1051 hospitals from January 1, 2009 to December 31, 2010. The mean age for all patient hospitalizations was 70, with 67% being 65 years of age or older. Figure 1 shows hospitalization rates (per 100,000 person-years) by age group. Those who were 85 years of age or older had the highest rate of atrial fibrillation hospitalizations. The five most common associated comorbidities were hypertension (66%), diabetes mellitus (25%), chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (21%), obesity (13%), and chronic kidney disease (12%). 70% of admissions came from the emergency room. The average length of stay was approximately 3 days with an overall in-hospital mortality rate of 0.80%.

Figure 1.

Atrial Fibrillation Hospitalization Rates

* Results based on calculating the proportion of the US population in each age group hospitalized with Atrial Fibrillation. US population based on US census data for each age group.

Table 1 summarizes the baseline characteristics of younger (mean age 54) versus older (mean age 78) patients. Females accounted for 33% of younger patients versus 59% of older patients (p <0.001). For younger patients, hypertension (57%), diabetes mellitus (23%), obesity (21%), chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (17%), and alcohol abuse (8%) were the most common comorbidities. For older patients, the most common comorbidities were hypertension (70%), diabetes mellitus (25%), chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (23%), chronic kidney disease (14%), and obesity (8%). While statistically different, there was no clinically meaningful difference in the rate of admission via the emergency department between groups (69% versus 70%).

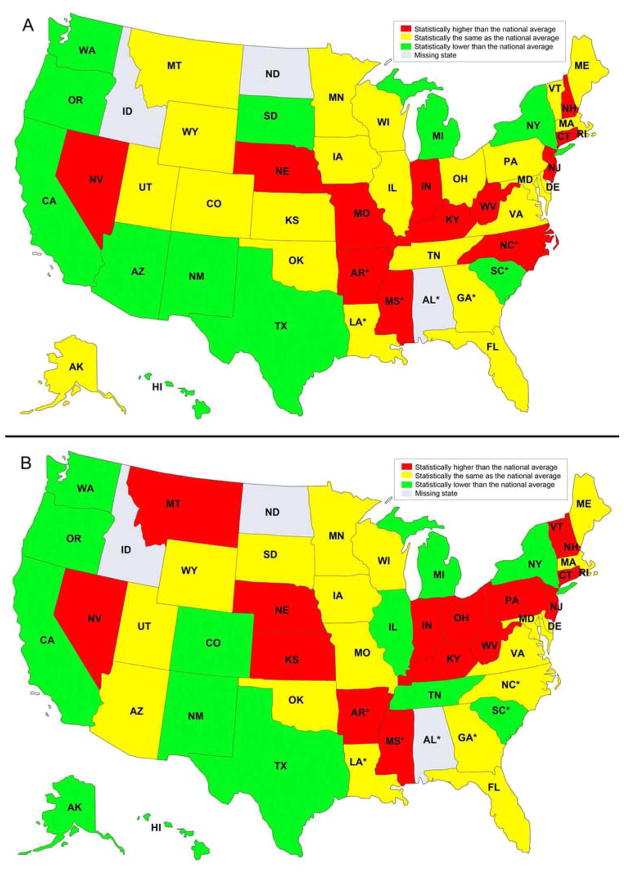

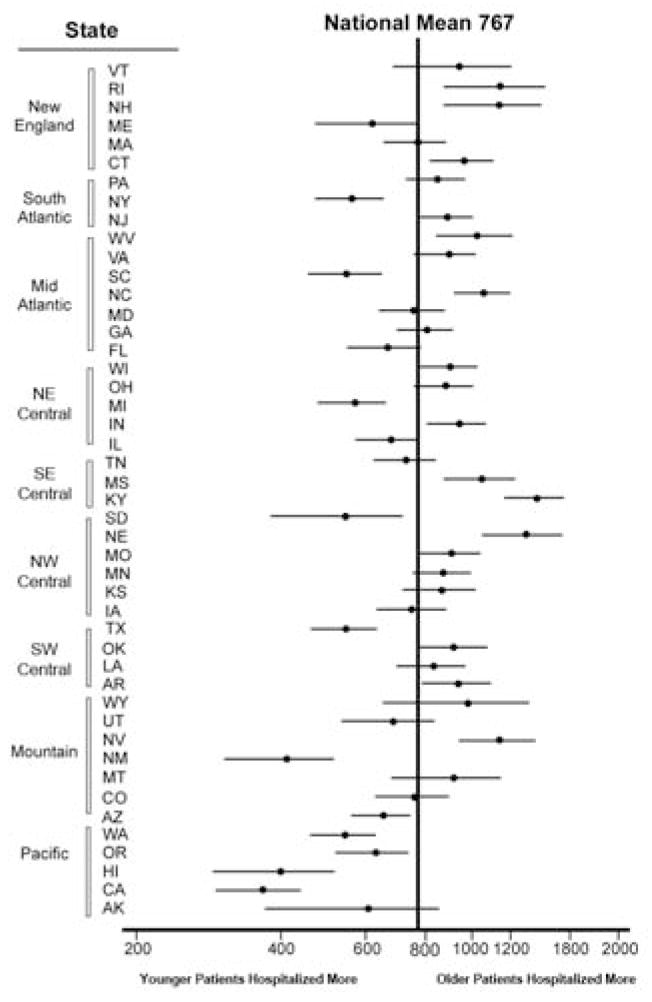

Remarkable geographic differences in the hospitalization rates were observed for both age groups. (Figure 2) States with high hospitalization rates did not necessarily correlate with those of the stroke belt. Vermont had the highest rate of hospitalization in younger patients while Kentucky had the highest rate in older patients. Figure 3 compares hospitalization rates by state and region for younger versus older age groups. Although no clear regional pattern was identified, the Pacific states do appear to hospitalize younger patients more than older patients.

Figure 2.

Atrial Fibrillation Hospitalization Rates by State (per 100,000 person-years) for A) Younger Patients versus B) Older Patients

* Indicates states classically included in the stroke belt23

Figure 3.

Difference in Atrial Fibrillation Hospitalization Rates (Per 100,000 person years) By State and Region between Younger and Older Patients

Table 2 presents outcomes including length of stay, major discharge dispositions, and inhospital mortality. There was a longer average length of stay (3.7 versus 2.9 days (p<0.001)) and higher in-hospital mortality (1% versus 0.3% (p<0.001)) for older versus younger patients respectively. Discharge disposition was also significantly different between groups (p<0.001), with older patients discharged to home less frequently (74% versus 84%) and to a skilled or intermediate care facility more frequently (10% versus 1%).

Table 2.

Hospitalization Characteristics of Younger versus Older Patients

| Hospital Characteristics | Age<65 Years | Age ≥65 Years | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| LOS- Mean Days (Interquartile Range) | 2.9 (1.0–4.0) | 3.7 (2.0–5.0) | <0.001 |

| Disposition- no. (%)¶ | <0.001 | ||

| Discharge Home | 53,081 (96) | 96,357 (83) | |

| Self Care | 50,909 (92) | 81,073 (70) | |

| Home Health | 2,172 (4) | 15,284 (13) | |

| SNF/ICF | 2,209 (4) | 16,053 (16) | |

| Hospice Care | 100 (0.2) | 1,170 (1.0) | |

| Mortality- no. (%) | 206 (0.003) | 1,421 (1) | <0.001 |

SNF= Skilled Nursing Facility, ICF= Intermediate Care Facility

Data excludes in-hospital mortalities and transfers to other hospitals (2.1 and 2.3% of older and younger patients respectively) given patients could have been calculated twice.

Discussion

Atrial Fibrillation: A Changing Demographic?

While the incidence of atrial fibrillation increases as a function of age, its incidence in younger patients in our analysis is substantial, with 33% of hospitalizations occurring in patients under age 65. Within the younger age group, those between the ages of 45 to 65 appear to carry the burden of disease. These results are comparable to that of other cardiovascular conditions such as congestive heart failure, in which approximately 29% of congestive heart failure hospitalizations are in patients under the age of 65.14 High atrial fibrillation hospitalization rates have not only direct financial costs but also indirect costs associated with decreased work productivity, a particular consideration in younger patients likely still active in the workforce.

Interestingly, a previous epidemiologic analysis based on four large population-based studies performed by Feinberg et al15 showed that 84% of patients with atrial fibrillation were over the age of 65. This is a much higher percentage than what was observed in our study. Importantly, our study examined the incidence of atrial fibrillation hospitalizations, whereas this analysis assessed incidence independent of hospitalization. It is therefore not possible to determine if this observed difference simply reflects a difference in rate of hospitalization versus diagnosis. However, this would require that younger patients be hospitalized for atrial fibrillation more often than older patients, a challenging supposition. Alternatively, it is possible that there has been an increase in its diagnosis in younger patients in recent years or an actual shift in epidemiology or treatment that is prompting increasing atrial fibrillation related hospitalizations in this group. Given the rising burden of obesity in the US population, and its known association with atrial fibrillation,16 this latter consideration is almost certainly a contributing factor.

The epidemiology of atrial fibrillation in younger patients appears to differ from that of older patients. As supported by previous literature,17,18 hypertension and diabetes mellitus were prevalent in both age groups. However, there were significant differences in other associated comorbidities. Obesity and alcohol were more often associated with atrial fibrillation in younger patients, while chronic kidney disease had a greater association in older patients. Given a larger proportion of older patients were female, it is possible that gender distribution is contributing to the difference in comorbidities seen. This will certainly require further exploration. As suggested by Rosiak et al,19 “lone atrial fibrillation,” as so often it is called in younger patients, may to some degree be a misnomer. Rather, there may be a different set of risk factors and comorbidities that warrant consideration in younger patients. However, lone atrial fibrillation has been shown to have greater heritability than does atrial fibrillation in association with known risk factors.20 Therefore, the younger group most likely includes a subset of patients with a genetic predisposition for this condition.

Our findings also have implications for the older age group. The high prevalence of chronic kidney disease has a substantial impact on both rhythm control and anticoagulation options, as many atrial fibrillation drugs require renal dosing. In the Randomized Evaluation of Long-Term Anticoagulation Therapy (Re-Ly) Trial,21 which prompted FDA approval of dabigatran for stroke prevention in patients with atrial fibrillation, fewer than one third of patients enrolled were over the age of 80 and fewer than 20 percent had a creatinine clearance less than 50ml/min. In our study, the average age of older patients hospitalized with a diagnosis of atrial fibrillation was 78, with approximately 14 percent having coexisting chronic kidney disease. Subgroup analysis from Re-Ly suggests increased bleeding risk in patients over age 75 treated with dabigatran,22 a particular concern given the observed age distribution in our analysis. This underscores the need to ensure that clinical trial participants parallel real-world patients in order to develop safe and efficacious treatment regimens.

Geographic Variation in Atrial Fibrillation

Given the greater burden of stroke for those with atrial fibrillation, we sought to determine the geographic distribution of atrial fibrillation hospitalizations in order to make comparisons with the so-called “stroke belt”. Traditionally, high stroke mortality is known to be a southeastern phenomenon with a 30–40% increase in stroke mortality in the stroke belt states as compared to the general US population.23 It should be noted that HCUP data for Alabama, one such state, is not currently available. While there was significant geographic variation in hospitalization rates in both the younger and older groups, this pattern did not correlate with the stroke belt states (Figure 2). This could be due to a number of factors. Other medical conditions place patients at risk for stroke,24 and the stroke belt data includes both hemorrhagic and ischemic stroke mortality. In addition, state variation in stroke mortality is likely largely driven by environmental factors. High atrial fibrillation hospitalizations alone may not explain high stroke mortality given that socioeconomic factors play a significant role in patient outcomes.25 This analysis also did not capture rates of anticoagulation or individual CHADS2 risk scores. Regional differences in practice patterns with respect to anticoagulation may contribute significantly to the risk of thromboembolic events.

In general, older patients were more likely to be hospitalized than younger patients in the northeast while the reverse was true in the western states. This could reflect geographic differences in medical practice, level of individual in these states, and/or socioeconomic factors. Given the increased risk of atrial fibrillation with increasing body mass index BMI,16 it is interesting to consider the role of obesity in the geographic distribution seen, particularly in the younger patients, who had notably higher rates of obesity. However, there did not appear to be a consistent correlation between national patterns of obesity and atrial fibrillation hospitalizations.26

Importantly, atrial fibrilation hospitalization rates may underrepresent its burden in patients who do not require inpatient medical care and/or are cared for by providers who opt not to admit the patient for drug loading or invasive procedures. Geographic variation may also be skewed by the willingness of individuals to seek medical care, a barrier that has been observed in traditionally underserved groups.27 Conversely, patients, particularly the uninsured, may be more likely to rely on the emergency room for their medical care. The designation as younger versus older patients is an important one, as younger patients may have different barriers to care than do older patients, who presumably have Medicare.

Outcomes in Atrial Fibrillation

The length of stay of older patients was significantly longer than younger patients, and while the mortality rate was quite low for both groups, it was significantly higher in the older age group. This is not surprising given the greater comorbidities in the older patients. Older patients were much more likely to receive home health care services or require transfer to a nursing facility than younger patients. While it is difficult to attribute this solely to atrial fibrillation and is likely also driven by other comorbidities, it does highlight the debilitated status of older patients discharged with atrial fibrillation.

Patients with atrial fibrillation are 3 times as likely to be rehospitalized than those with other conditions.5 This has obvious implications for both the patient and the medical system as a whole. The reasons for high rehospitalization rates are unclear but could be attributed to a number of factors beyond the physical condition of the patient. Going forward, it will be essential to identify aspects of patient care during the hospitalization or upon discharge that could be modified in order to potentially decrease rehospitalization rates. Although it was not possible to know which patients had repeat admissions using the current data set, it can be hypothesized that a subset of patients account for the majority of rehospitalizations. Future research will need to focus on these so-called high-risk patients in order to develop ways in which to improve outpatient care and therefore minimize the need for hospitalization.

Limitations

There are a number of limitations in our study. We are making the assumption that the hospitals involved in the analysis are representative of the general population. Furthermore, whenever using ICD-9 coding, the data analysis depends on accurate coding by the hospitals involved. The analysis also does not account for repeat hospitalizations by the same patient, those hospitalized primarily for other conditions, or the health care burden of outpatient management. Finally, the impact of race and ethnicity on hospitalizations also could not be fully assessed, as a smaller proportion of states accurately reported these patient characteristics.28

Conclusions and Future Directions

By revealing significant differences in atrial fibrillation hospitalization patterns between younger and older patients, this study provides important epidemiologic information to further understand the complexities of atrial fibrillation. Patient age may be a crucial factor in identifying risk factors for the disease and developing population-based schemes to improve outcomes. Further research is needed to understand the association between atrial fibrillation and identified comorbidities, the specific socioeconomic factors impacting hospitalizations, and the quality of care needed in order to work towards reducing the financial and societal burden of the disease.

Clinical Significance.

Younger patients account for a substantial minority of atrial fibrillation hospitalizations.

There is no clear correlation between hospitalizations and incidence of stroke.

Younger patients are generally healthier but have a different distribution of risk factors.

A significant portion of elderly patients may not be a candidate for available pharmacologic treatments.

Older patients have higher atrial fibrillation associated morbidity and mortality.

Acknowledgments

Funding Source: None

Footnotes

Sahar Naderi, MD MHS: no conflicts of interest

Yun Wang, PhD: no conflicts of interest

Amy L. Miller, MD PhD: no conflicts of interest

Fátima Rodriguez, MD MPH: no conflicts of interest

Mina K. Chung, MD: no conflicts of interest

Martha J. Radford, MD: no conflicts of interest

JoAnne M. Foody, MD: no conflicts of interest

All authors had access to the data and a role in writing this manuscript.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Camm J. Atrial fibrillation--an end to the epidemic? Circulation. 2005;112:iii. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Risk factors for stroke and efficacy of antithrombotic therapy in atrial fibrillation. Analysis of pooled data from five randomized controlled trials. Arch Intern Med. 1994;154:1449–1457. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Benjamin EJ, Wolf PA, D’Agostino RB, et al. Impact of atrial fibrillation on the risk of death: the Framingham Heart Study. Circulation. 1998;98:946–952. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.98.10.946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Go AS, Hylek EM, Phillips KA, et al. Prevalence of diagnosed atrial fibrillation in adults: national implications for rhythm management and stroke prevention: the AnTicoagulation and Risk Factors in Atrial Fibrillation (ATRIA) Study. JAMA: the journal of the American Medical Association. 2001;285:2370–2375. doi: 10.1001/jama.285.18.2370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kim MH, Johnston SS, Chu BC, et al. Estimation of total incremental health care costs in patients with atrial fibrillation in the United States. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2011;4:313–320. doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.110.958165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Miyasaka Y, Barnes ME, Gersh BJ, et al. Secular trends in incidence of atrial fibrillation in Olmsted County, Minnesota, 1980 to 2000, and implications on the projections for future prevalence. Circulation. 2006;114:119–125. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.595140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Benjamin EJ, Chen PS, Bild DE, et al. Prevention of atrial fibrillation: report from a national heart, lung, and blood institute workshop. Circulation. 2009;119:606–618. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.825380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chugh SS, Blackshear JL, Shen WK, et al. Epidemiology and natural history of atrial fibrillation: clinical implications. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2001;37:371–378. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(00)01107-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Furberg CD, Psaty BM, Manolio TA, et al. Prevalence of atrial fibrillation in elderly subjects (the Cardiovascular Health Study) The American journal of cardiology. 1994;74:236–241. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(94)90363-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Blackshear JL, Kopecky SL, Litin SC, et al. Management of atrial fibrillation in adults: prevention of thromboembolism and symptomatic treatment. Mayo Clin Proc. 1996;71:150–160. doi: 10.4065/71.2.150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Project HCaU, editor. Overview of the Nationwide Inpatient Sample. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chen J, Normand SL, Wang Y, et al. National and regional trends in heart failure hospitalization and mortality rates for Medicare beneficiaries, 1998–2008. JAMA: the journal of the American Medical Association. 2011;306:1669–1678. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.1474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dodson JA, Wang Y, Desai MM, et al. Outcomes for mitral valve surgery among Medicare fee-for-service beneficiaries, 1999 to 2008. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2012;5:298–307. doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.112.966077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hall MJ, Levant S, DeFrances C Statistics NCfH, editor. NCHS data brief. Hyattsville, MD: 2012. Hospitalization for congestive heart failure: United States, 2000–2010. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Feinberg WM, Blackshear JL, Laupacis A, et al. Prevalence, age distribution, and gender of patients with atrial fibrillation. Analysis and implications Arch Intern Med. 1995;155:469–473. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wanahita N, Messerli FH, Bangalore S, et al. Atrial fibrillation and obesity--results of a meta-analysis. American heart journal. 2008;155:310–315. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2007.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Healey JS, Connolly SJ. Atrial fibrillation: hypertension as a causative agent, risk factor for complications, and potential therapeutic target. The American journal of cardiology. 2003;91:9G–14G. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(03)00227-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ostgren CJ, Merlo J, Rastam L, et al. Atrial fibrillation and its association with type 2 diabetes and hypertension in a Swedish community. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2004;6:367–374. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-8902.2004.00358.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rosiak M, Dziuba M, Chudzik M, et al. Risk factors for atrial fibrillation: Not always severe heart disease, not always so ‘lonely’. Cardiol J. 2010;17:437–442. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lubitz SA, Ozcan C, Magnani JW, et al. Genetics of atrial fibrillation: implications for future research directions and personalized medicine. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2010;3:291–299. doi: 10.1161/CIRCEP.110.942441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Connolly SJ, Ezekowitz MD, Yusuf S, et al. Dabigatran versus warfarin in patients with atrial fibrillation. The New England journal of medicine. 2009;361:1139–1151. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0905561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Eikelboom JW, Wallentin L, Connolly SJ, et al. Risk of bleeding with 2 doses of dabigatran compared with warfarin in older and younger patients with atrial fibrillation: an analysis of the randomized evaluation of long-term anticoagulant therapy (RE-LY) trial. Circulation. 2011;123:2363–2372. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.004747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rich DQ, Gaziano JM, Kurth T. Geographic patterns in overall and specific cardiovascular disease incidence in apparently healthy men in the United States. Stroke. 2007;38:2221–2227. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.107.483719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Goldstein LB, Adams R, Alberts MJ, et al. Primary prevention of ischemic stroke: a guideline from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association Stroke Council: cosponsored by the Atherosclerotic Peripheral Vascular Disease Interdisciplinary Working Group; Cardiovascular Nursing Council; Clinical Cardiology Council; Nutrition, Physical Activity, and Metabolism Council; and the Quality of Care and Outcomes Research Interdisciplinary Working Group. Circulation. 2006;113:e873–923. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000223048.70103.F1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schauer DP, Moomaw CJ, Wess M, et al. Psychosocial risk factors for adverse outcomes in patients with nonvalvular atrial fibrillation receiving warfarin. Journal of general internal medicine. 2005;20:1114–1119. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2005.0242.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Prevention CfDCa, editor. Overweight and Obesity. Atlanta: 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ayanian JZ, Weissman JS, Schneider EC, et al. Unmet health needs of uninsured adults in the United States. JAMA: the journal of the American Medical Association. 2000;284:2061–2069. doi: 10.1001/jama.284.16.2061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Quality AfHRa, editor. Nationwide Inpatient Sample Data Elements. [Google Scholar]