Graphical abstract

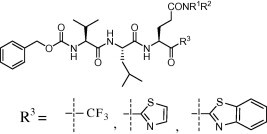

A series of trifluoromethyl, benzothiazolyl and thiazolyl ketone-containing peptidic compounds were synthesized and evaluated in vitro against SARS-CoV 3CLpro.

Keywords: SARS-CoV, Protease inhibitors, Drug design, Synthesis

Abstract

A series of trifluoromethyl, benzothiazolyl or thiazolyl ketone-containing peptidic compounds as SARS-CoV 3CL protease inhibitors were developed and their potency was evaluated by in vitro protease inhibitory assays. Three candidates had encouraging results for the development of new anti-SARS compounds.

In November 2002, it was reported an emergence of severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) as a highly contagious and fatal respiratory disease infecting more than 8000 individuals of which 9.6% patients died within a few months.1 Due to highly efficient international cooperation, two groups rapidly reported that a novel coronavirus (CoV) was the causative agent of SARS.2, 3 CoV encodes a chymotrypsin-like protease (3CLpro) that plays a pivotal role in the replication of the virus.4 3CLpro, a cysteine protease, is functionally analogous to the main picornavirus protease 3Cpro with a catalytic dyad (Cys-145 and His-41) in the active site. Cys acts as a nucleophile, whereas His functions as a general base.5, 6 In order to find compounds that can inhibit SARS-CoV, numerous 3CLpro inhibitors have been described, including C 2-symmetric diols,7 bifunctional aryl boronic acids,8 keto-glutamine analogs,9 isatin derivatives,10 α,β-unsaturated esters,11 anilide,12 benzotriazole13 as well as glutamic acid and glutamine peptides possessing a trifluoromethyl ketone group as reported by us and our collaborators since 200614 and recently by another group.15 However, no effective therapy has been developed so far and it is still a matter of necessity to discover new potent structures in case the disease re-emerges.

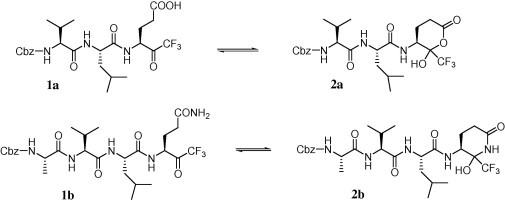

In our previous report, two compounds (Scheme 1 , 1a,b) were found to be moderate SARS-CoV 3CLpro inhibitors (K i = 116 and 134 μM, respectively).14a As mentioned by Cai and co-workers in 2006, the moderate activity can be the result of the formation of a typical cyclic structure (Scheme 1, compounds 2a,b) that is not expected to interact effectively with the active site of SARS-CoV 3CLpro.16

Scheme 1.

Previously reported trifluoromethyl ketone-containing peptides and their corresponding cyclic non-active counterparts.

Herein, we report our results on improving the inhibitory activity of these compounds, by focusing on two strategies. First, keeping the trifluoromethylketone moiety in place, we investigated chemical modifications on the side chain of Glu or Gln residue at the P1 position, in order to block the formation of the cyclic structure (Scheme 1) and modulate the hydrogen bonding ability of this P1 position toward the active site, as well as modifying the amino acid residues at the P2 and P3 positions. Second, we investigated a replacement of the chemical warhead of the inhibitor, that is, the trifluoromethyl unit, by other moieties such as electron-withdrawing thiazolyl and benzothiazolyl groups. We believe that this modification would be valuable for enhancing the reactivity of the covalent-adduct formation to the active site cysteine residue in SARS-CoV 3CLpro.

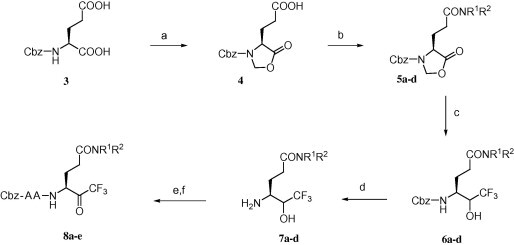

From a synthetic point of view, the preparation of the target compounds was envisioned following the synthetic routes illustrated in Scheme 2, Scheme 3, Scheme 4 . Compounds 8a–e were prepared from Cbz-l-Glu-OH (3) that was converted to the corresponding oxazolidinone acid 4 under the conditions described by Moore et al.17 Amides 5a–d were next prepared by coupling compound 4 with four kinds of amines using a standard HOBt–EDC·HCl coupling method for peptides, resulting in excellent yields. Compounds 5a–d were then converted in a one-pot reaction to the corresponding trifluoromethylalcohols 6a–d, whose Cbz group was de-protected after silica gel column chromatography, and the amino function in the resultant compounds 7a–d was coupled to the appropriate peptide fragments.14 The peptide fragments were synthesized according to known procedures.14, 18 Finally, the resulting peptides were directly engaged in the last oxidation step affording pure target compounds 8a–e with moderate overall yields after RP-HPLC purification by a CH3CN:(0.1% TFA/H2O) system.

Scheme 2.

Reagents and conditions: (a) paraformaldehyde, p-TsOH·H2O, toluene, reflux, 2 h, 98%; (b) HNR1R2, HOBt, EDC·HCl, DMF, 0 °C–rt, overnight, 80–98%; (c) CsF, CF3Si(CH3)3, THF, sonication, rt, 3 h then MeOH, rt, 30 min then NaBH4, rt, overnight, 48–61%; (d) H2, Pd/C (10%), MeOH, rt, overnight, 100%; (e) Cbz-AA-OH, HOBt, EDC·HCl, DMF, 0 °C–rt, overnight; (f) Dess–Martin periodinane, CH2Cl2, rt, 16 h, EtOAc then filtration through Celite followed by HPLC purification.

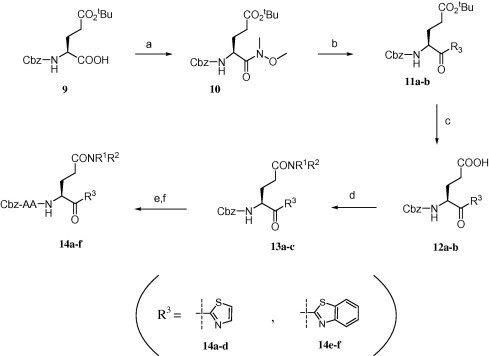

Scheme 3.

Reagents and conditions: (a) N,O-dimethylhydroxylamine hydrochloride, EDC·HCl, HOBt, TEA, DMF, rt, 12 h, 90%; (b) thiazole or benzothiazole, n-BuLi, −78 °C, 2.5 h, 70%; (c) formic acid, rt, 12 h, 100%; (d) HNR1R2, EDC·HCl, HOBt, DMF, rt, 12 h, 90%; (e) triflic acid, DCM, rt, 5 min, 100% (f) Cbz-AA-OH, HOBt, EDC·HCl, DMF, rt, 12 h followed by HPLC purification.

Scheme 4.

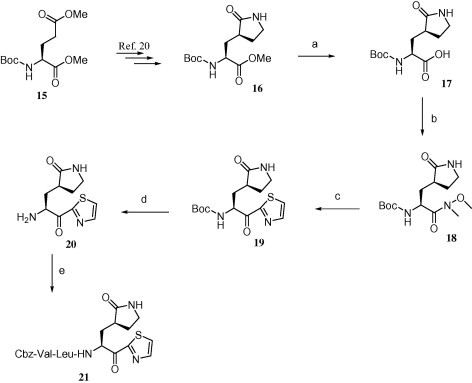

Reagents and conditions: (a) LiOH, THF/H2O, 92%; (b) HN(OCH3)CH3, EDC·HCl, HOBt, DMF, rt, 12 h, 90%; (c) thiazole, n-BuLi, −78 °C, 2.5 h, 70%; (d) TFA/H2O, 4 h, >99%; (e) Cbz-Val-Leu-OH, EDC·HCl, HOBt, DMF, rt, 12 h followed by HPLC purification.

Derivatives 14a–d with a thiazole-ketone and 14e,f with a benzothiazole-ketone structure at the P1 residue were prepared as shown in Scheme 3. Cbz-Glu(tBu)-OH 9 was converted to Weinreb amide 10 and successively coupled to thiazole or benzothiazole in the presence of n-BuLi as a base to afford ketones 11a,b.19 After deprotection of the tert-butyl group by HCOOH, the resultant carboxyl group of compounds 12a,b was coupled to the amines to obtain compounds 13a–c, followed by coupling of the peptide fragments based on a similar approach depicted in Scheme 2. Compounds 14a–f were obtained with moderate yields after HPLC purification.

Compound 21, which has a pyrrolidone structure at the P1 side chain, was synthesized by a different approach as shown in Scheme 4. Lactam ester 16 was prepared from commercially available N-Boc-l-(+)-glutamic acid dimethyl ester 15 by following a previously published procedure.20 Lactam ester 16 was then hydrolyzed to obtain the lactam acid 17, followed by the synthetic steps depicted in Scheme 3 to get desired compound 21.

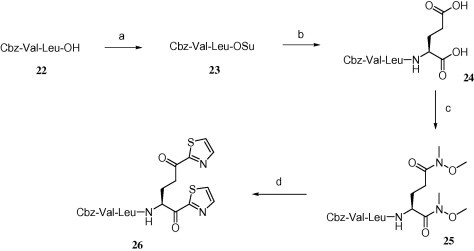

Dithiazolyl compound 26 was synthesized starting from Cbz-Val-Leu-OH 22 (Scheme 5 ) that was first converted to succinimide ester 23 followed by treatment with l-glutamic acid to obtain compound 24. Dicarboxylate compound 24 was then converted to the corresponding α,γ-double-Weinreb amide (25), followed by a treatment with 2 equiv of thiazole in the presence of n-BuLi to afford the desired N-Cbz-protected dithiazolylketone compound (26).

Scheme 5.

Reagents and conditions: (a) N-hydroxysuccinimide, DCC, THF, 0 °C–rt, 12 h, 93%; (b) l-glutamic acid, NaOH solution (aq), dioxane, 4 h, 0 °C–rt, 90%; (c) HN(OCH3)CH3, EDC·HCl, HOBt, DMF, rt, 12 h, 90%; (d) thiazole, n-BuLi, −78 °C, 2.5 h followed by HPLC purification.

The inhibitory activities (K i) of the first series of compounds against SARS-CoV 3CLpro are shown in Table 1 . The inhibition assay was performed using a procedure mentioned earlier.14a In our previous report, compounds 1a,b (Scheme 1) were found to be moderate SARS-CoV 3CLpro inhibitors with K i values of 116 and 135 μM, respectively (Table 1, entries 1 and 2). These compounds were used as leads for structural optimization in the development of potent SARS-CoV 3CLpro inhibitors.

Table 1.

Structure and activity of the synthesized CF3-inhibitors

| Entry | Compound | Structurea | Kib (μM) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1a |  |

116 ± 14 |

| 2 | 1b |  |

135 ± 32 |

| 3 | 8a |  |

363 ± 128 |

| 4 | 8b |  |

21.0 ± 4.3 |

| 5 | 8c |  |

34.1 ± 4.1 |

| 6 | 8d |  |

297 ± 49 |

| 7 | 8e |  |

584 ± 167 |

Cbz, benzyloxycarbonyl.

Ki, inhibition constant against SARS-CoV 3CLpro.

Compound 8a was our first attempt at modifying the P1 residue by converting the γ-carboxylic acid of compound 1a to a N,N-diethylamide. However, compound 8a exhibited lower inhibitory activity than lead compound 1a. A plausible reason for the observed low activity could be attributed to a disruption of hydrogen bonding interactions at the P1 position with the active site of the enzyme, or an unfavorable steric hindrance to a covalent bond formation at the CF3-ketone moiety with the active site cysteine residue in the enzyme. On the other hand, replacements of P1 N,N-diethylamide in compound 8a with N-morpholine- and N,N-methylbenzyl-amides increased the inhibitory activity (Table 1, entries 4 and 5). Indeed, the activity of compounds 8b and 8c with K i values of 21.0 and 34.1 μM, respectively, was fivefold higher affinity than reference compound 1a. Next, to develop smaller sized inhibitors, we prepared CF3-ketone compounds 8d and 8e containing the same P1 structure as compound 8a but different peptide chain lengths, because peptide chain length plays a significant role in the inhibition of enzymes by forming crucial hydrogen bonding interactions. However, the observed change in activity was negligible with either an increase or decrease of one residue in the peptide chain length (compare entries 3, 6 and 7).

In the commonly adopted mechanism of inhibition of SARS-CoV 3CLpro, a covalent bond is formed between the carbonyl group located at the warhead of the inhibitor and the active site cysteine residue in the enzyme. Modifying the electronegativity at this warhead carbonyl moiety could accelerate the covalent bond formation. Hence, as a second series of investigations, the trifluoromethylketone moiety was replaced with an electron withdrawing thiazolyl or benzothiazolyl counterpart.

As shown in Table 2 , when compared to trifluoromethylketone containing compound 8b, corresponding compound 14a with thiazolylketone exhibited drastically decreased inhibition (K i = 478 μM; entry 2). However, a thiazolylketone derivative 14b with N,N-diethylamide at the P1 side chain slightly increased inhibitory activity (K i = 112 μM; entry 3) over the CF3-ketone derivative 8a with a more bulky N,N-diisopropylamide structure. Moreover, when the pyrrolidine structure was adapted to the P1 side chain, thiazolylketone derivative 21 (entry 4) drastically increased inhibitory activity with a K i value of 2.2 μM. Slightly smaller and rigid cyclic amide structure seemed to be well accommodated by the S1 site. The introduction of a thiazolylketone to the P1 side chain resulted in a compound (entry 5) that exhibited decreased but relatively strong activity (K i = 45.2 μM) in comparison to pyrrolidine derivative 21. Inhibitory activity was again decreased by reducing the peptide chain length of compound 14b (compare entries 3, 6 and 7). A little improvement in inhibitory activity was observed when the warhead thiazole was replaced by a benzothiazole (compare entries 3, 7–9). Of the compounds synthesized, inhibitor 21 possessing P1-pyrrolidone and P1′-thiazole was found to be the most potent SARS-CoV 3CLpro inhibitor.

Table 2.

Structure and activity of the synthesized thiazolyl and benzothiazolyl inhibitors

| Entry | Compound | Structurea | Kib (μM) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 8b |  |

21.0 ± 4.3 |

| 2 | 14a |  |

478 ± 193 |

| 3 | 14b |  |

112 ± 34 |

| 4 | 21 |  |

2.20 ± 0.8 |

| 5 | 26 |  |

45.2 ± 7.8 |

| 6 | 14c |  |

462 ± 145 |

| 7 | 14d |  |

614 ± 139 |

| 8 | 14e |  |

49.3 ± 10 |

| 9 | 14f |  |

159 ± 25 |

Cbz, benzyloxycarbonyl.

Ki, inhibition constant against SARS-CoV 3CLpro.

Our studies suggest that all the synthesized inhibitors are tight-binding substrate mimetics that target the active site of SARS-3CLpro.22 Similar to the trifluoromethyl ketone compounds, the thiazole and benzothiazole ketone compounds did not show an increase in inhibition after they were equilibrated with the protease for 10 min. Thus, the inhibition of the compounds to the protease was not time dependent indicating a reversible tight-binding interaction with the protease. Moreover, to better understand the potent activity of compound 21 with the enzyme, computational molecular studies were performed (Fig. 1 ).

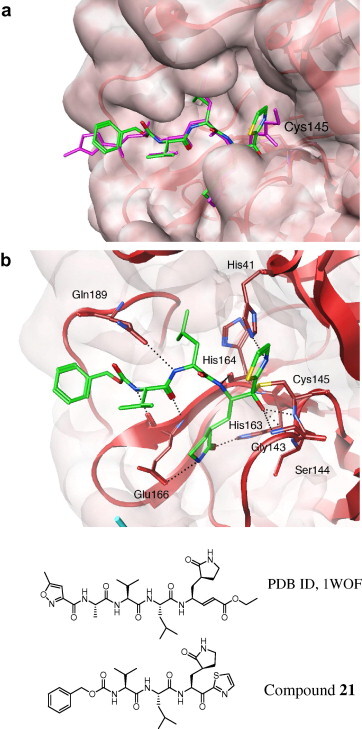

Figure 1.

Molecular dynamics simulated pose of compound 21 (green stick) bound to SARS-CoV 3CLpro (PDB 1WOF, with red and cyan ribbons with molecular surfaces). (a) Overlapped view with an original vinyl ester ligand (pink stick). (b) Contacted residues with hydrogen bonding interactions (dotted line).

A binding model of 21 with SARS-CoV 3CLpro was simulated using a modeling package (moe 2007.09, Chemical Computing Group, Inc., Montreal, Canada). The initial conformation of 21 was built by changing a structurally similar ligand (Fig. 1) obtained from X-ray crystal data (PDB ID, 1WOF, K i = 10.7 μM obtained from Ref. 21). Several energy minimization processes with an MMFF94x force field were additionally performed in a water soak environment around the inhibitor, followed by a molecular dynamics simulation. During the simulation, the moieties from P1 to P3 interacted in a similar manner as the original ligand except for the thiazolyl ketone and benzyloxycarbonyl moieties (Fig. 1a). The oxoanion of the ketone generated from an attack of Cys145, interacted with the amide backbone of Gly143, Ser144 and Cys145 (Fig. 1b). The nitrogen in the thiazole was also in contact with His41 through hydrogen bonding interactions. These interactions indicate an acceptance of the unique ketone. On the other hand, the benzyloxycarbonyl group barely made hydrophobic interactions, suggesting a possibility for further optimizations of the moiety.

In conclusion, we disclosed the inhibitory potency of compound 21, containing a P1-pyrrolidone and warhead thiazolyl unit, as a SARS-CoV 3CLpro inhibitor. The measured inhibitory activity coupled with possible structure modifications revealed by 3D docking give us new directions for a fast development of much more potent inhibitors. Further investigations on this new family of compounds are currently in progress in our laboratory.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by The Frontier Research Program; The 21st Century coe Program from The Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology, Japan; and Japan Society for the Promotion of Science’s Post-Doctoral Fellowship for Foreign Researchers. E.F. also acknowledges support from a grant from the National Institutes of Health (GM 57144). The manuscript was thoroughly revised by Dr. Jeffrey-Tri Nguyen.

References and notes

- 1.He J.-F., Peng G.-W., Min J., Yu D.-W., Liang W.-L., Zhang S.-Y., Xu R.-H., Zheng H.-Y., Wu X.-W., Xu J., Wang Z.-H., Fang L., Zhang X., Li H., Yan X.-G., Lu J.-H., Hu Z.-H., Huang J.-C., Wan Z.-Y., Hou J.-L., Lin J.-Y., Song H.-D., Wang S.-Y., Zhou X.-J., Zhang G.-W., Gu B.-W., Zheng H.-J., Zhang X.-L., He M., Zheng K., Wang B.-F., Fu G., Wang X.-N., Chen S.-J., Chen Z., Hao P., Tang H., Ren S.-X., Zhong Y., Guo Z.-M., Liu Q., Miao Y.-G., Kong X.-Y., He W.-Z., Li Y.-X., Wu C.-I., Zhao G.-P., Chiu R.W.K., Chim S.S.C., Tong Y.-K., Chan P.K.S., Tam J.S., Lo Y.M.D. Science. 2004;303:1666. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ksiazek T.G., Erdman D., Goldsmith C.S., Zaki S.R., Peret T., Emery S., Tong S., Urbani C., Comer J.A., Lim W., Rollin P.E., Dowell S.F., Ling A.-E., Humphrey C.D., Shieh W.-J., Guarner J., Paddock C.D., Rota P., Fields B., DeRisi J., Yang J.-Y., Cox N., Hughes J.M., LeDuc J.W., Bellini W.J., Anderson L.J. N. Eng. J. Med. 2003;348:1953. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa030781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Frosten C., Günther S., Preiser W., Van Der Werf S., Brodt H.-R., Backer S., Rabenau H., Panning M., Kolesnikova L., Fouchier R.A.M., Berger A., Burguiére A.-M., Cinatl J., Eickmann M., Escriou N., Grywna K., Kramme S., Manuguerra J.-C., Müller S., Rickerts V., Stürmer M., Vieth S., Klenk H.-D., Osterhaus A.D.M.E., Schmitz H., Doerr H.W.N. N. Eng. J. Med. 2003;348:1967. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa030747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rota P.A., Oberste M.S., Monroe S.S., Nix W.A., Campagnoli R., Icenogle J.P., Peñaranda S., Bankamp B., Maher K., Chen M., Tong S., Tamin A., Lowe L., Frace M., DeRisi J.L., Chen Q., Wang D., Erdman D.D., Peret T.C.T., Burns C., Ksiazek T.G., Rollin P.E., Sanchez A., Liffick S., Holloway B., Limor J., McCaustland K., Olsen-Rasmussen M., Fouchier R., Günther S., Osterhaus A.D.M.E., Drosten C., Pallansch M.A., Anderson L.J., Bellini W.J. Science. 2003;300:1394. doi: 10.1126/science.1085952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Anand K., Ziebuhr J., Wadhwani P., Mesters J.R., Hilgenfeld R. Science. 2003;300:1763. doi: 10.1126/science.1085658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Snijder E.J., Bredenbeek P.J., Dobbe J.C., Thiel V., Ziebuhr J., Poon L.L.M., Guan Y., Rozanov M., Spaan W.J., Gorbalenya A.E. J. Mol. Biol. 2003;331:991. doi: 10.1016/S0022-2836(03)00865-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.(a) Wu C.-Y., Jan J.-T., Ma S.-H., Kuo C.-J., Juan H.-F., Cheng E.Y.-S., Hsu H.-H., Huang H.-C., Wu D., Brik A., Liang F.-S., Liu R.-S., Fang J.-M., Chen S.-T., Liang P.-H., Wong C.-H. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2004;101:10012. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0403596101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Shao Y.-M., Yang W.-B., Peng H.-P., Hsu M.-F., Tsai K.-C., Kuo T.-H., Wang A.H.-J., Liang P.-H., Lin C.-H., Yang A.-S., Wong C.-H. ChemBioChem. 2007;8:1654. doi: 10.1002/cbic.200700254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bacha U., Barrila J., Velasquez-Campoy A., Leavitt S.A., Freire E. Biochemistry. 2004;43:4906. doi: 10.1021/bi0361766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jain R.P., Petterson H.I., Zhang J., Aull K.D., Fortin P.D., Huitema C., Eltis L.D., Parrish J.C., James M.N.G., Wishart D.S., Vederas J.C. J. Med. Chem. 2004;47:6113. doi: 10.1021/jm0494873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chen L.-R., Wang Y.-C., Lin Y.-W., Chou S.-Y., Chen S.-F., Liu L.-T., Wu Y.-T., Kuo C.-J., Chen T.S.-S., Juang S.-H. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2005;15:3058. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2005.04.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.(a) Ghosh A.K., Xi K., Ratia K., Santarsiero B.D., Fu W., Harcourt B.H., Rota P.A., Baker S.C., Johnson M.E., Mesecar A.D. J. Med. Chem. 2005;48:6767. doi: 10.1021/jm050548m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Shie J.-J., Fang J.-M., Kuo T.-H., Kuo C.-J., Liang P.-H., Huang H.-J., Wu Y.-T., Jan J.-T., Cheng E.Y.-S., Wong C.-H. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2005;13:5240. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2005.05.065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Ghosh A.K., Xi K., Grum-Tokars V., Xu X., Ratia K., Fu W., Houser K.V., Baker S.C., Johnson M.E., Mesecar A.D. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2007;17:5876. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2007.08.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shie J.-J., Fang J.-M., Kuo T.-H., Kuo C.-J., Liang P.-H., Huang H.-J., Yang W.-B., Lin C.-H., Chen J.-L., Wu Y.-T., Wong C.-H. J. Med. Chem. 2005;48:4469. doi: 10.1021/jm050184y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wu C.-Y., King K.-Y., Kuo C.-J., Fang J.-M., Wu Y.-T., Ho M.-Y., Liao C.-L., Shie J.-J., Liang P.-H., Wong C.-H. Chem. Biol. 2006;13:4469. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2005.12.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.(a) Sydnes M.O., Hayashi Y., Sharma V.K., Hamada T., Bacha U., Barrila J., Freire E., Kiso Y. Tetrahedron. 2006;62:8601. doi: 10.1016/j.tet.2006.06.052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Bacha U., Barrila J., Gabelli B., Kiso Y., Amzel L.M., Freire E. Chem. Biol. Drug Des. 2008;72:34. doi: 10.1111/j.1747-0285.2008.00679.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shao Y.-M., Yang W.-B., Kuo T.-H., Tsai K.-C., Lin C.-H., Yang A.-S., Liang P.-H., Wong C.-H. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2008;16:4652. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2008.02.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhang H.-Z., Zhang H., Kemnitzer W., Tseng B., Cinatl J., Jr., Michaelis M., Doerr H.W., Cai S.X. J. Med. Chem. 2006;49:1198. doi: 10.1021/jm0507678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Luesch H., Hoffman D., Hevel J.M., Becker J.E., Golakoti T., Moore R.E. J. Org. Chem. 2003;68:83. doi: 10.1021/jo026479q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kuo C.J., Chi Y.H., Hsu J.T.A., Liang P.H., Leavitt S.A., Freire E. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2004;318:862. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2004.04.098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Maynard G.D., Cheng H.C., Kane J.M., Staeger M.A. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 1993;4:753. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tian Q., Nayyar N.K., Babu S., Chen L., Tao J., Lee S., Tibbetts A., Moran T., Liou J., Guo M., Kennedy T.P. Tetrahedron Lett. 2001;42:6807. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yang H., Xie W., Xue X., Yang K., Ma J., Liang W., Zhao Q., Zhou Z., Pei D., Ziebuhr J., Hilgenfeld R., Yuen K.Y., Wong L., Gao G., Chen S., Chen Z., Ma D., Bartlam M., Rao Z. PLoS Biol. 2005;3:1742. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0030324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Briefly, the inhibitors were equilibrated with the enzyme for 10 min before the addition of the substrate to determine their activity respectively. The kinetic reaction was initiated by the addition of the substrate which has a sequence reminiscent of the N-terminal auto-cleavage site of the protease, flanked by the fluorescent groups, dabcyl and edans. The rate of substrate cleavage can be detected by an increase in fluorescence that can be monitored over time. The Ki or the inhibition constant is an indication of the compound as potency.