Abstract

Background

Afterschool programs (ASPs) can provide opportunities for children to accumulate moderate-to-vigorous physical activity (MVPA). The optimal amount of time ASPs should allocate for physical activity (PA) on a daily basis to ensure children achieve policy-stated PA recommendations remains unknown.

Methods

Children (n = 1248, 5–12 years) attending 20 ASPs wore accelerometers up to 4 non-consecutive week days for the duration of the ASPs during spring 2013 (February-April). Daily schedules were obtained from each ASP.

Results

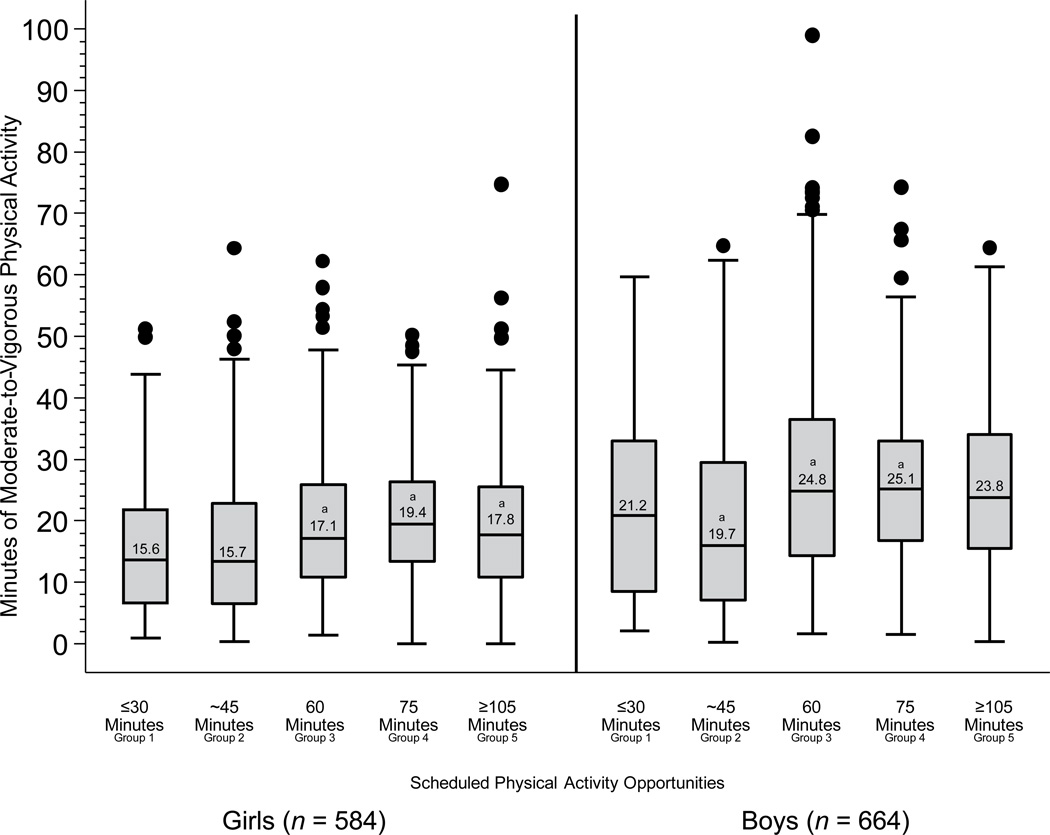

Across 20 ASPs, three programs allocated ≤30 min, five approximately 45 min, four 60 min, four 75 min, and four ≥105 min for PA opportunities daily (min.d−1). Children accumulated the highest levels of MVPA in ASPs that allocated ≥60 min.d−1 for PA opportunities (24.8–25.1 min.d−1 for boys and 17.1–19.4 min.d−1 for girls) versus ASPs allocating ≤45 min.d−1 for PA opportunities (19.7 min.d−1 and 15.6 min.d−1 for boys and girls, respectively). There were no differences in the amount of MVPA accumulated by children among ASPs that allocated 60 min.d−1 (24.8 min.d−1 for boys and 17.1 min.d−1 for girls), 75 min.d−1 (25.1 min.d−1 for boys and 19.4 min.d−1 for girls) or ≥105 min.d−1 (23.8 min.d−1 for boys and 17.8 min.d−1 for girls). Across ASPs, 26% of children (31% for boys and 14% for girls) met the recommended 30 minutes of MVPA.

Conclusions

Allocating more than one hour of PA opportunities is not associated with an increase in MVPA during ASPs. Allocating 60 min.d−1, in conjunction with enhancing PA opportunities, can potentially serve to maximize children’s accumulation of MVPA during ASPs.

Keywords: Policy, MVPA, children, obesity

Introduction

In the U.S., over 8 million children (ages 5–13 years) attend afterschool programs (ASPs) annually.1 Typically, ASPs operate for approximately three hours following the end of a regular school day (~3–6 PM) and offer a variety of activities for children that include academics, enrichment (e.g., arts and crafts), and physical activity (PA).2 Nationwide, ASP organizations (e.g. The National Afterschool Association, California Department of Education) recommend programs allocate anywhere between 30–60 minutes for children’s PA opportunities, with half of this allocated PA time to be spent in moderate to vigorous physical activity (MVPA) each day.2,3

It is well documented that the majority of ASPs fail to meet the PA recommendations endorsed by national ASP organizations.4–6 A potential reason for this is that current ASP policy lacks empirically-based evidence regarding the optimal amount of PA time ASPs should allocate in order to meet the PA recommendations (e.g. all children attain 30 minutes of MVPA per day in ASPs3).4–6 In other words, the optimal amount of time ASPs should allocate to ensure children achieve policy-stated PA recommendations is unknown. The purpose of this study was to examine the association between ASPs’ allocated PA time and the amount of MVPA children accumulate while in attendance.

Methods

Participants and Setting

Afterschool programs were defined as community-based programs that take place immediately after the regular school day (typically 3:00–6:00 PM); are located in either a school setting or take place in a community organization outside the school environment (e.g. YMCA, Boys and Girls Club, faith organization); are available daily throughout the academic year (Monday-Friday); and provide a combination of scheduled activities such as time for snack, homework, enrichment and physical activity.5 Twenty afterschool programs, representing 13 different organizations were randomly selected from an existing registry of 535 ASPs in South Carolina and invited to participate in an intervention targeting healthy eating and PA. The information presented herein represents baseline (March-April 2013) information collected as part of an intervention study. Program eligibility consisted of operating within 1.5 hr drive from the university and classification as an ASP as defined above. Across the 20 ASPs, mean enrollment was 92 children (range 30 to 162). The average percentage of the population and percent of families in poverty status, based on program zip code in the 2010 US Census data (http://factfinder2.census.gov), were 15.4% and 11.4% (range 1.4% to 50.5%), respectively. The average population per square mile for all 20 ASPs was 1206.1 (range 149.5 to 2254.3). The ethnic/racial composition of the ASPs was 57% White non-Hispanic and 38% African American. Descriptive characteristics of the 20 ASP sites are presented in Table 1. All procedures were approved by the university’s institutional review board.

Table 1.

Descriptive Characteristics for After-School Programs (ASPs) Stratified by Mean Allocated Physical Activity (PA) Minutes

| Scheduled PA Groups |

ASPs (n) |

Allocated PA (minutes per day)a |

range (minutes per day) |

PA sessions (number per day)a |

sd | PA session duration (minutes per session)a |

sd | ASP Type (n) | Enrollment (number of children)a |

(range) | % Females at ASP a |

% (range) |

% AA at ASP a |

% (range) |

ASP Duration (minutes per day)a |

range (minutes per day) |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S | C | F | ||||||||||||||||

| Group1 b (≤30 minutes) |

3 | 25 | (15 – 30) | 1.0 | 0.0 | 25 | 8.7 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 58 | (30 – 87) | 51 | (48 – 71) | 50 | (28 – 83) | 185 | (135 – 210) |

| Group2 c (~45 minutes) |

5 | 44 | (40 – 45) | 1.2 | 0.4 | 36.6 | 12.1 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 93 | (30 – 160) | 43 | (31 – 56) | 64 | (18 – 100) | 203 | (120 – 240) |

| Group3 (60 minutes) |

4 | 60 | - | 1.0 | 0.0 | 60 | 0.0 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 86 | (37 – 136) | 44 | (40 – 51) | 40 | (6 – 96) | 213 | (180 – 225) |

| Group4 (75 minutes) |

4 | 75 | - | 1.5 | 0.6 | 50 | 20.0 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 98 | (30 – 143) | 44 | (33 – 55) | 20 | (0 – 56) | 198 | (180 – 210) |

| Group5 d (≥105 minutes) |

4 | 124 | (105 – 150) | 2.8 | 1.3 | 45 | 31.5 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 112 | (51 – 162) | 44 | (35 – 51) | 16 | (0 – 40) | 216 | (200 – 255) |

| Total | 20 | 66 | (15 – 150) | 9 | 7 | 4 | 92 | (30 – 162) | 47 | (33 – 73) | 38 | (0 – 100) | 204 | (135 – 255) | ||||

Mean Values

One ASP allocated 15 minutes of PA, two allocated 30 minutes of PA

One ASP allocated 40 minutes of PA, four allocated 45 minutes of PA

Two ASPs allocated 105 minutes of PA, one 135 minutes of PA, and one 150 minutes of PA

Tables Key: S = School, C = Community, F = Faith; AA = African American; ‘ - ‘ = no range

Allocated Physical Activity

Allocated PA was obtained from a daily schedule of activities. A hard copy of the program schedule was collected from each program leader on data collection days. Allocated PA was defined as any opportunities for children to be physically active, as indicated on the schedule. For example, ‘3:30 pm – 4:10 pm: Basketball in Gymnasium’, would represent 40 minutes of allocated PA for a particular ASP. Allocated times for PA opportunities were summed to represent the total number of allocated minutes for PA on a given day.

Physical Activity Protocol

Children’s PA was collected using GT3X+ ActiGraph accelerometers (Shalimar, FL) on a minimum of four nonconsecutive days (Monday – Thursday). The epoch was set at five-second intervals7 to improve the ability to capture the transitory PA patterns of children.8,9 When arriving at the programs, each child was fitted with an accelerometer and the arrival time was recorded (monitor time-on) by trained research staff. Children were then allowed to participate in the normally scheduled activities. Research staff continuously monitored the entire ASP for compliance in wearing the accelerometers. Before a child departed from a program, research staff removed the accelerometer and recorded the time of departure (monitor time-off). This procedure was performed throughout the duration of the study. Data were collected Mondays through Thursdays. Widely used cutpoint thresholds for MVPA (>2296 CPM)10 and sedentary behavior (<100 CPM)11 were used. A valid day of accelerometer data was total wear time (time-off minus time-on) ≥60 minutes.12,13

Analyses

The 20 ASPs were placed into the following 5 groups based on their daily allocated PA time – 3 ASPs allocated an average of 25 min.d−1 (Group 1, range 15–30, median 30 min), 5 ASPs allocated an average of 44 min.d−1 (Group 2, range 40–45 min, median 45 min), 4 ASPs 60 min.d−1 (Group 3), 4 ASPs 75 min.d−1 (Group 4), and 4 ASPs an average of 124 min.d−1 (Group 5, range 105–150 min, median 105 min). Comparisons across groups were made to examine differences in accumulated MVPA for boys and girls, separately. Comparisons were made using mixed model quantile regressions accounting for children nested within ASPs and modeling the 50th percentile (median of distribution) due to the non-normal distribution of MVPA. Time in attendance, race, and age were controlled for in all analyses. Additionally, comparisons were made across the groups on the mean percentage of children who met 30 minutes of MVPA. A mixed model logistic regression was used to investigate whether allocated PA time was associated with an increased likelihood of meeting the 30 minutes of MVPA called for in nationwide ASP standards.6 All analyses were conducted using Stata (v.12.0, College Station, TX).

Results

A total of 1,248 children (5–12 yrs, 47% girls), representing 68% of the total number of children enrolled across the ASPs, wore accelerometers for up to 4 days (mean 2.5 days; range 1–4 days), resulting in a total of 3,119 days of valid accelerometer monitoring. Table 1 displays the mean durations of ASP (beginning to end of program) stratified by allocated PA time (i.e., groups 1–5). The mean duration of an ASP was 204 min.d−1 (range 135 to 255 min) with an average allocated PA time of 66 min.d−1 (range 15 to 150 min).

Table 2 illustrates the mean percentage of children per allocated PA group who met 30 minutes per day of MVPA, accompanied by odds ratios with ASPs that allocated 60 minutes of PA opportunities (group 3) serving as the referent. Across the 20 ASPs, 26% of children met the recommended 30 minutes of MVPA, with 31% and 14% of boys and girls, respectively, accumulating 30 minutes or more of MVPA per day. Odds ratios indicated that allocating less than 60 min.d−1 of PA was associated with a decreased likelihood of meeting the recommended 30 minutes of MVPA, while allocating more than 60 min.d−1 for PA did not result in an increased likelihood of meeting this standard (Table 2).

Table 2.

Percent of Children Meeting Recommended 30 minutes of Moderate-to-Vigorous Physical Activity (MVPA)

| Allocated Physical Activity Time (minutes per day) a |

% Children Meeting 30 minutes of MVPA a |

% Boys Meeting 30 minutes of MVPA a |

% Girls Meeting 30 minutes of MVPA a |

Odds Ratio c | 95% Confidence Interval |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group1 (≤30 minutes) |

25 | 22 | 29 | 11 | 0.64 | 0.48 to 0.87 |

| Group2 (~45 minutes) |

44 | 20 | 22 | 13 | 0.56 | 0.44 to 0.72 |

| Group3b (60 minutes) |

60 | 31 | 36 | 16 | - | - |

| Group4 (75 minutes) |

75 | 28 | 33 | 16 | 0.89 | 0.71 to 1.13 |

| Group5 (≥105 minutes) |

124 | 29 | 34 | 15 | 0.92 | 0.73 to 1.16 |

| All ASPs | 66 | 26 | 31 | 14 | N/A | N/A |

Mean Values

Referent Group

Odds Ratio for boys and girls

Box plots of the distribution of MVPA min.d−1 for boys and girls across the 5 groupings of allocated PA time are presented in Figure 1. Girls attending an ASP allocating 60 min.d−1 and ≥75 min.d−1 for PA opportunities accumulated greater amounts of MVPA compared to those attending ASPs allocating ≤45 min.d−1. Boys attending an ASP allocating ≥60 min.d−1 for PA opportunities accumulated greater amounts of MVPA than those attending ASPs allocating ≤45 min.d−1. For both boys and girls, accumulated MVPA min.d−1 did not differ among ASPs that allocated ≥60 min d−1 for PA opportunities.

Discussion

Findings from this study suggest 1) children attending ASPs that allocate ≤45 min.d−1 for PA opportunities accumulate substantially less MVPA than children attending ASPs that allocate ≥60 min.d−1 for PA opportunities and 2) children attending ASPs that allocate ≥75 min.d−1 for PA opportunities do not accumulate greater amounts of MVPA than children attending ASPs allocating 60 min.d−1 for PA opportunities. These results are somewhat intuitive, with ASPs that allocate the least amount of time for PA opportunities having children that accumulate the least amount of MVPA. Surprisingly, allocating more than 60 min.d−1 for PA opportunities did not result in further accumulation of MVPA. In fact, almost doubling the amount of allocated PA time from 60 min.d−1 to ≥105 min.d−1 resulted in comparable amounts of MVPA (24.8 min.d−1 vs. 23.8 min.d−1). In support of these findings, as allocated PA increased, the likelihood of meeting 30 minutes of MVPA, a widely accepted recommendation for ASPs,6 did not increase. Evidently, ASPs may need to reevaluate the amount of time they allocate for children’s PA in their programs, with specific regard towards the purpose and value of these existing PA opportunities.

Although allocating more time for PA is an obvious approach to increasing children’s MVPA,14,15 results from this study show that once 60 or more minutes of PA are allocated, this strategy may not produce the desired increases in children’s MVPA. Figure 1 suggests that a “Goldilocks Zone” may exist, where an optimal amount of PA allocated (60–75 minutes) corresponds to the highest accumulation of MVPA for both sexes. These findings can provide valuable insight for ASP leaders where managing scheduling demands of competing interests such as snack, academics, and enrichment activities often leave a restricted amount of time for physical activity opportunities. Given ASPs are called upon to help children accumulate half of their daily 60 min of MVPA,6,16 that a majority of children attending ASPs fail to accumulate policy-recommended amounts of MVPA,4,17 and that PA represents only one of several other important programmatic elements (e.g., homework, enrichment), maximizing MVPA opportunities 18,19 during pre-existing PA opportunities appears to be a more feasible solution to meeting existing MVPA recommendations in ASPs,6,16,20 rather than allocating additional time for PA opportunities. Maximizing PA can be achieved through professional development training focused on delivery of organized games that facilitate MVPA, working with ASP leaders to develop detailed schedules to minimize transition times, and providing a range of activities that appeal to both boys and girls.21–23

A strength of this study is the size and diversity of the sample. To date, this is one of the largest studies conducted in the ASP setting. The diversity of the programs in this study is also a strength. Different types of programs (e.g. school, community, faith), composed of children with diverse ethnic backgrounds were included in the sample. Additionally, physical activity was measured via accelerometery, the gold standard of measurement for free living physical activity in children. A limitation is the MVPA estimates are for the entire duration of the ASP, not only during the allocated PA time. This limits the ability to accurately delineate exactly when the MVPA was accumulated, thus making it difficult to further analyze the benefits or drawbacks of allocating PA into one single session per day, or breaking it down into shorter sessions. However, the majority of the accumulated MVPA is expected to occur during allocated PA opportunities, thus, the estimates presented herein are reflective of these opportunities.

In conclusion, this study challenges the concept that increasing allocated time for PA opportunities will lead to subsequent increases in MVPA for children attending ASPs. Responsible parties need to address the time they apportion to children’s PA with respect to the quality and intentionality of these available experiences to maximize MVPA levels.

Figure 1. Distribution of Moderate-to-Vigorous Physical Activity minutes/day for boys and girls across 5 groupings of allocated time.

a Statistical significance (p<0.05) in MVPA accumulated between allocating ≤30 min.d−1 PA

Acknowledgements

Funding Source

Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Heart, Lung, And Blood Institute of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number 7R01HL11278702. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Potential conflicts of interest: None

References

- 1.America After 3pm Report. 2009. Afterschool Alliance. [Google Scholar]

- 2.The National Afterschool Association. NAA Standards for Healthy Eating and Physical Activity in Out-Of-School Time Programs. 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 3.California Department of Education. California After School Physical Activity Guidelines. 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Beets MW, Rooney L, Tilley F, Beighle A, Webster C. Evaluation of policies to promote physical activity in afterschool programs: are we meeting current benchmarks? Preventive medicine. 2010;51(3):299–301. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2010.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Beets MW. Enhancing the translation of physical activity interventions in afterschool programs. American Journal of Lifestyle Medicine. 2012;6(4):328–341. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Beets MW, Wallner M, Beighle A. Defining standards and policies for promoting physical activity in afterschool programs. Journal of School Health. 2010;80(8):411–417. doi: 10.1111/j.1746-1561.2010.00521.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bailey RC, Olson J, Pepper SL, Porszaz J, Barstow TJ, Cooper DM. The level and tempo of children's physical activities: An observational study. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 1995;27:1033–1041. doi: 10.1249/00005768-199507000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Baquet G, Stratton G, Van Praagh E, Berthoin S. Improving physical activity assessment in prepubertal children with high-frequency accelerometry monitoring: a methodological issue. Prev Med. 2007 Feb;44(2):143–147. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2006.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vale S, Santos R, Silva P, Soares-Miranda L, Mota J. Preschool children physical activity measurement: importance of epoch length choice. Pediatr Exerc Sci. 2009 Nov;21(4):413–420. doi: 10.1123/pes.21.4.413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Evenson KR, Catellier DJ, Gill K, Ondrak KS, McMurray RG. Calibration of two objective measures of physical activity for children. J Sports Sci. 2008 Dec;26(14):1557–1565. doi: 10.1080/02640410802334196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Matthews CE, Chen KY, Freedson PS, et al. Amount of time spent in sedentary behaviors in the United States, 2003–2004. Am J Epidemiol. 2008 Apr 1;167(7):875–881. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwm390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Beets MW, Huberty J, Beighle A. Physical Activity of Children Attending Afterschool Programs Research- and Practice-Based Implications. Am J Prev Med. 2012 Feb;42(2):180–184. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2011.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Trost SG, Rosenkranz RR, Dzewaltowski D. Physical activity levels among children attending after-school programs. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2008 Apr;40(4):622–629. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0b013e318161eaa5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Beets MW, Huberty J, Beighle A, et al. Impact of policy environment characteristics on physical activity and sedentary behaviors of children attending afterschool programs. Health Education and Behavior. doi: 10.1177/1090198112459051. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rosenkranz RR, Welk GJ, Dzewaltowski DA. Environmental correlates of objectively measured physical activity and sedentary behavior in after-school recreation sessions. J Phys Act Health. 2011 Sep;8(Suppl 2):S214–S221. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Beets MW, Webster C, Saunders R, Huberty JL. Translating policies into practice: a framework for addressing childhood obesity in afterschool programs. Health Promotion Practice. 2013;14(2):228–237. doi: 10.1177/1524839912446320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Beets MW, Shah R, Weaver RG, Huberty J, Beighle A, Moore JB. Physical Activity in Afterschool Programs: Comparison to Physical Activity Policies. Journal of Physical Activity & Health. doi: 10.1123/jpah.2013-0135. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Coleman KJ, Geller KS, Rosenkranz RR, Dzewaltowski DA. Physical Activity and Healthy Eating in the After-School Environment. Journal of School Health. 2008;78(12):633–640. doi: 10.1111/j.1746-1561.2008.00359.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Huberty JL, Beets MW, Beighle A, McKenzie T. Association of Staff Behaviors and Afterschool Program Features to Physical Activity: Findings from Movin'Afterschool. Journal of physical activity & health. 2012 doi: 10.1123/jpah.10.3.423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Weaver RG, Beets MW, Webster C, Beighle A, Huberty J. A Conceptual Model for Training After-School Program Staffers to Promote Physical Activity and Nutrition. The Journal of school health. 2012 Apr;82(4):186–195. doi: 10.1111/j.1746-1561.2011.00685.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ajja R, Beets MW, Huberty J, Kaczynski AT, Ward DS. The Healthy Afterschool Activity and Nutrition Documentation Instrument. Am J Prev Med. 2012 Sep;43(3):263–271. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2012.05.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Beets MW, Weaver RG, Moore JB, et al. From Policy to Practice: Strategies to Meet Physical Activity Standards in YMCA Afterschool Programs. Am J Prev Med. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2013.10.012. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Weaver RG, Beets MW, Saunders R, Webster C, Beighle A. A Comprehensive Professional Development Training’s Effect on Afterschool Program Staff Behaviors to Promote Healthy Eating and Physical Activity. Journal Public Health Management and Practice. doi: 10.1097/PHH.0b013e3182a1fb5d. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]