Abstract

Psoriasis is a common inflammatory skin disease. It is known to be a complex condition with multifactorial mode of inheritance, however the associations between particular pathogenic pathways remain unclear. A novel report on the pathogenesis of psoriasis has recently included the genetic determination of the skin barrier dysfunction. In this paper, we focus on specific genetic variants associated with formation of the epidermal barrier and their role in the complex pathogenesis of the disease.

Keywords: psoriasis, epidermal differentiation complex, late cornified envelope

Introduction

Psoriasis is a common chronic inflammatory skin disease. The combination of genetic, immunological and environmental factors is considered to play a pivotal role in the induction of the disease [1]. Up to date, psoriasis has been classified as a complex disease, depending on gene–gene and gene–environment interactions as well as various disturbances in innate and adaptive immunity. This hypothesis has been confirmed by genetic studies.

Linkage analysis of large family cohorts led to the identification of major susceptibility loci located on various autosomal chromosomes. To date, the strongest association with psoriasis has been proven in psoriasis susceptibility 1 (PSORS1) locus on chromosome 6p21 [2]. The region consists of 250-kb within the major histocompatibility complex class I (MHC class I). Among 10 genes identified in PSORS1 locus, the strongest correlation with psoriasis in various ethnic groups has been described in the case of HLA-Cw6 allele [3]. As in other disorders characterized by a polygenic inheritance model with a low penetration of genes, HLA-Cw-*-06 is responsible for 35–50% of predisposition to the early-onset psoriasis. This suggests the presence of other polymorphisms outside the MHC region, which together with HLA-Cw-*-06, form a specific genetic panel correlated to the significantly higher risk of developing the disease.

Recent genome-wide association studies (GWAS) have led to the identification of numerous candidate genes that may play a role in the pathogenesis of psoriasis. These include novel genetic polymorphisms of genes involved in the interleukin 23, 12, 17 (IL-23, IL-12, IL-17) and nuclear factor κB (NF-κB)-dependent signaling pathway [4]. These findings support the immune-mediated background in the pathogenesis of psoriasis. Recently, the researchers’ attention has been focused on identification of novel genetic markers connected with functioning of the skin barrier in psoriasis. Interesting results obtained by GWAS analyses have led to the formulation of the hypothetical role of a genetically determined skin barrier dysfunction in the pathogenesis of psoriasis. In this paper, we present current reports on specific genetic variants associated with the epidermal barrier function and their role in the complex pathogenesis of the disease.

Cornified envelope

The following stages in the keratinocyte differentiation process are characterized by the expression of specific genes encoding different structural proteins. The terminal step of the keratinization process is associated with the formation of a highly specialized insoluble protein–lipid structure called the cornified envelope (CE). At the molecular level, the very stable structure of cornified envelope is based on the formation of isopeptide bonds catalyzed by transglutaminases (TGs): TG1, TG3 and TG5 [5]. At the initial stage of this process, the cytoskeleton is formed by linking the keratin intermediate filaments (KIFs) with filaggrin. Next, the transglutaminases catalyze the joining of involucrin, loricrin, trichohyalin, small proline-rich proteins (SPRPs) and members of a recently discovered family of late envelope proteins (LEPs) and the family of S100 proteins [5–8]. Finally, the process is followed by the attachment of lipids, including ceramides, to the protein structure of cornified envelope.

The role of cornified envelope is crucial for proper functioning of the epidermal barrier. Therefore, any abnormalities in the expression of genes encoding proteins that are a part of the envelope structure or participate in the enzymatic catalysis process, may result in disturbances at different stages of keratinocyte differentiation and eventually lead to the dysfunction of the epidermal barrier. Recent genome wide association studies have focused on the role of specific candidate genes involved in the process of cornified envelope formation in the pathogenesis of psoriasis vulgaris.

Epidermal differentiation complex genes

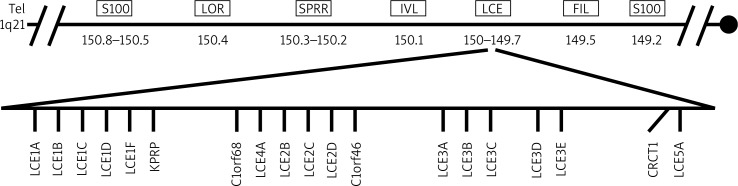

Epidermal differentiation complex (EDC), located within PSORS4 locus on chromosome 1q21, harbors genes which are expressed at various stages of the keratinization process (Figure 1). Up to date, 45 genes have been identified within the complex. Proteins encoded by epidermal differentiation complex genes are divided into three families: a group of cornified envelope precursor proteins (including, loricrin – LOR, involucrin – IVL, small proline-rich proteins – SPRPs and late cornified envelope proteins – LCE), a group of proteins binding the keratin filaments (including, filaggrin – FLG, trichohyalin – TCHH, filaggrin 2 – FLG2, repetin – RPTN, hornerin – HRNR, cornulin – CRNN) and a group of calcium binding proteins S100 [9–11].

Figure 1.

Epidermal differentiation complex

Studies on the role of the genetic factor of skin barrier abnormalities in the pathogenesis of atopic dermatitis (AD), led to the discovery of two independent null mutations (R510X and 2282del4) in the filaggrin gene in different cohorts of patients with AD [12]. The results have revolutionized the hypothesis on the primary role of disturbances in immune response in the pathogenesis of AD. Due to the location of the FLG gene in or near PSORS4 locus, both loss-of-function mutations in FLG gene, – R510X and 2282del4, have also been studied in cohorts of patients with psoriasis. The genetic analyses conducted in German and Dutch populations have not shown any significant association of null mutations in the FLG gene with the risk of psoriasis [13, 14]. On the other hand, the distinct results of the study by Kim et al. provide evidence for the correlation of psoriasis with a low expression of genes encoding filaggrin and loricrin. In the study, 9 skin biopsies taken from both psoriatic plaques and perilesional skin have been analyzed by real-time PCR (qPCR) method. The qPCR results demonstrating a low expression of the filaggrin and loricrin genes have been confirmed by immunohistochemical staining of the encoded proteins in the skin biopsies [15]. Additionally, the reduced expression of the loricrin gene and its significant correlation to the risk of psoriasis have been also demonstrated by independent analyses carried out by Chen et al. and Giardina et al. [11, 16]. Furthermore, in vitro study results by Kim et al. proved a significant role of tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) in the regulation of filaggrin and loricrin expression through N-terminal protein kinase c-Jun-dependent pathway [15]. As in the case of TNF-α, the Th2-mediated cytokines regulate the expression of genes encoding epidermal differentiation complex proteins, but probably these pathways are related to different signaling patterns. The reduced filaggrin, involucrin and loricrin expression, regulated by Th-2-mediated cytokines, has been confirmed independently in the populations of patients with AD and psoriasis [15, 17, 18]. These reports are supportive of the fact that the epidermal barrier genes are not constitutive and their expression is regulated by various immunological factors.

The family of S100 proteins comprises 25 members. These proteins are a part of cornified envelope and are characterized by low molecular mass. The role of S100 proteins includes activation of the innate immune response by stimulating production of proinflammatory cytokines, including TNF-α. An increased expression of S100A4, S100A7, S100A8, S100A9 and S100A12 has been observed in psoriatic skin lesions, however its role in the pathogenesis of the disease remains unclear. The study by Wolf et al. has shown that the increased expression of S100A7 and S100A15 in the skin of mice is associated with induction of an inflammatory process that leads to development of histological features characteristic of perilesional skin changes in the course of psoriasis [19].

Recently, the researchers’ interest has been focused on the family of genes encoding late cornified envelope proteins (LCE proteins). This group comprises representatives divided into six subfamilies described as LCE-1-LCE-6 [10]. The LCE gene cluster is located within PSORS4 locus on chromosome 1q21.3 and is a part of the EDC complex. Late cornified envelope proteins are involved in the terminal phase of keratinocyte differentiation process [20]. The study by Jackson et al. has shown a different expression of respective subsets of these genes. Additionally, the family of LCE1 and LCE2 is highly expressed in the skin, whereas the expression of the LCE3 group is undetectable or detectable at very low levels within the epithelial cells [10]. Considering the association of the LCE gene cluster with psoriasis, interesting results of genetic analyses demonstrate a common deletion comprising LCE3B and LCE3C genes (LCE3C_LCE3B-del). The results of the study by de Cid et al. from Western European cohort showed a variable number of copies of genes (copy number variations, CNVs) associated significantly with the LCE family in patients with psoriasis. Further analysis led to a discovery of the common deletion of the two aforementioned genes, which significantly correlated to the risk of psoriasis development [21]. Supportive results were obtained in other studies from ethnically diverse cohorts, which finally have been confirmed in the meta-analysis by Riveira-Munoz et al. [22–25]. Moreover, genetic analysis in the Chinese population led to the discovery of single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) remaining in linkage disequilibrium (LD) with LCE3C_LCE3B-del in patients with psoriasis [26]. The role of the deletion in the pathogenesis of the disease is still unclear, however the fact of its high incidence in the general population (accounting for approximately 60–70%) is also interesting. Physiologically, the LCE3 protein family is undetectable in the skin, however the expression of the LCE3 genes may be induced by physical traumas. This suggests a major role of LCE3 proteins in the process of damage repair in the skin. Considering the probable role in the pathogenesis of psoriasis, the loss of function of LCE3B and LCE3C genes can lead to a significant impairment of cornified envelope formation, which can result in dysfunction of the damage repair process in the epidermis [21]. Furthermore, the disturbances in the epidermal barrier function may result in promotion of penetration of the exogenous antigens, which may re-stimulate or induce pro-inflammatory response in psoriasis. Finally, the interesting results of genetic studies on the presence of interactions between HLA-Cw-*-06 and LCE3C_LCE3B-del in patients with psoriasis seem to support the complex nature of the disease [21, 25–27].

Cystatins

Recent identification of novel genetic polymorphisms associated with the cystatin gene (CSTA) has been proven to contribute to psoriasis development [28]. The CSTA gene located within the PSORS5 locus on chromosome 3q21, encodes a protein with the average molecular mass of 11 kDa. Cystatin A is an endogenous cysteine protease inhibitor, a precursor protein for cornified envelope, and regulates a desquamation process as well as differentiation of keratinocytes. In the study by Vasilopoulos et al., a significant association of two haplotypes (CSTA TCC, CSTA TTC) with psoriasis has been discovered. What is more, the study results provide strong evidence for interaction between these haplotypes and HLA-C-w*-06, which means that the disease risk seems to be higher for individuals who carry risk alleles at both CSTA and HLA-C [29].

Another protein involved in the regulation of the skin barrier formation process is cystatin M/E, encoded by CST6. High expression levels of CST6 have been reported in the stratum granulosum of normal human skin and the secretory coils of eccrine sweat glands [30]. Cystatin M/E proved to be an inhibitor of asparaginyl endopeptidase legumain, cathepsin L (CTSL), cathepsin V (CTSV) as well as a controlling factor in the process of cross-linking mediated by transglutaminase 3 (TGM3) during terminal differentiation of keratinocytes. Dysregulation in the pathway controlled by cystatin M/E leads to disturbances in the desquamation process which results in abnormalities in skin barrier functioning. In the study by Cheng et al., a decreased cystatin M/E expression level has been observed in psoriatic skin lesions [31].

Conclusions

Although psoriasis is generally regarded as an immunologically mediated disorder, results of the recent genetic studies confirm the significant role of particular genes involved in the formation of the skin barrier in the pathogenesis of the disease. This provides a novel viewpoint to the complex genetic background of psoriasis.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Griffiths CE, Barker JN. Pathogenesis and clinical features of psoriasis. Lancet. 2007;370:263–71. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61128-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Capon F, Munro M, Barker J, et al. Searching for the major histocompatibility complex psoriasis susceptibility gene. J Invest Dermatol. 2002;118:745–51. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1747.2002.01749.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nair RP, Stuart PE, Nistor I, et al. Sequence and haplotype analysis supports HLA-C as the psoriasis susceptibility 1 gene. Am J Hum Genet. 2006;78:827–51. doi: 10.1086/503821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shabgah AG, Fattahi E, Shahneh FZ. Interleukin-17 in human inflammatory diseases. Postep Derm Alergol. 2014;31:256–61. doi: 10.5114/pdia.2014.40954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Candi E, Schmidt R, Melino G. The cornified envelope: a model of cell death in the skin. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2005;6:328–40. doi: 10.1038/nrm1619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nemes Z, Steinert PM. Bricks and mortar of the epidermal barrier. Exp Mol Med. 1999;31:5–19. doi: 10.1038/emm.1999.2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Broome AM, Ryan D, Eckert RL. S100 protein subcellular localization during epidermal differentiation and psoriasis. J Histochem Cytochem. 2003;51:675–85. doi: 10.1177/002215540305100513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Marshall D, Hardman MJ, Nield KM, Byrne C. Differentially expressed late constituents of the epidermal cornified envelope. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:13031–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.231489198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhao XP, Elder JT. Positional cloning of novel skin-specific genes from the human epidermal differentiation complex. Genomics. 1997;45:250–8. doi: 10.1006/geno.1997.4952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jackson B, Tilli CM, Hardman MJ, et al. Late cornified envelope family in differentiating epithelia – response to calcium and ultraviolet irradiation. J Invest Dermatol. 2005;124:1062–70. doi: 10.1111/j.0022-202X.2005.23699.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chen H, Toh TKL, Szeverenyi I, et al. Association of skin barrier genes within the PSORS4 locus is enriched in Singaporean Chinese with early-onset psoriasis. J Invest Dermatol. 2009;129:606–14. doi: 10.1038/jid.2008.273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Palmer CN, Irvine AD, Terron-Kwiatkowski A, et al. Common loss-of-function variants of the epidermal barier protein filaggrin are a major predisposing factor for atopis dermatitis. Nat Genet. 2006;38:441–6. doi: 10.1038/ng1767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Huffmeier U, Traupe H, Oji V, et al. Loss-of-function variants of the filaggrin gene are not major susceptibility factors for psoriasis vulgaris or psoriatic arthritis in German patients. J Invest Dermatol. 2007;127:1367–70. doi: 10.1038/sj.jid.5700720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Thyssrn J, Johansen J, Carlsen B, et al. The filaggrin null genotypes R501X and 2282del4 seem not to be associated with psoriasis: results from general population study and meta-analysis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2012;26:782–4. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2011.04107.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kim BE, Howell MD, Guttman-Yassky E, et al. TNF-alpha downregulates filaggrin and loricrin through c-Jun N-terminal kinase: role for TNF-alpha antagonists to improve skin barrier. J Invest Dermatol. 2011;131:1272–9. doi: 10.1038/jid.2011.24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Giardina E, Capon F, De Rosa MC, et al. Characterization of the loricrin (LOR) gene as a positional candidate for the PSORS4 psoriasis susceptibility locus. Ann Hum Genet. 2004;68:639–45. doi: 10.1046/j.1529-8817.2004.00118.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Howell MD, Kim BE, Gao P, et al. Cytokine modulation of atopic dermatitis filaggrin skin expression. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2007;120:150–5. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2007.04.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kim BE, Leung DY, Boguniewicz M, et al. Loricrin and involucrin expression is down-regulated by Th2 cytokines through STAT-6. Clin Immunol. 2008;126:332–7. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2007.11.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wolf R, Mascia F, Dharamsi A, et al. Gene from a psoriasis susceptibility locus primes the skin for inflammation. Sci Transl Med. 2010;2:61ra90. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3001108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mischke D, Korge BP, Marenholz I, et al. Genes encoding structural proteins of epidermal cornification and S100 calcium-binding proteins form a gene complex (”epidermal differentiation complex”) on human chromosome 1q21. J Invest Dermatol. 1996;106:989–92. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12338501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.de Cid R, Riveira-Munoz E, Zeeuwen PL, et al. Deletion of the late cornified envelope LCE3B and LCE3C genes as a susceptibility factor for psoriasis. Nat Genet. 2009;41:211–5. doi: 10.1038/ng.313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Huffmeier U, Bergboer JG, Becker T, et al. Replication of LCE3C-LCE3B CNV as a risk factor for psoriasis and analysis of interaction with other genetic risk factors. J Invest Dermatol. 2010;130:979–84. doi: 10.1038/jid.2009.385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Li M, Wu Z, Chen G, et al. Deletion of the late cornified envelope genes LCE3C and LCE3B is associated with psoriasis in a Chinese population. J Invest Dermatol. 2011;131:1639–43. doi: 10.1038/jid.2011.86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Xu L, Li Y, Zhang X, et al. Deletion of LCE3C and LCE3B genes is associated with psoriasis in a northern Chinese population. Br J Dermatol. 2011;165:882–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2011.10485.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Riveira-Munoz E, He SM, Escaramis G, et al. Meta-analysis confirms the LCE3C_LCE3B deletion as a risk factor for psoriasis in several ethnic groups and finds interaction with HLA-Cw6. J Invest Dermatol. 2011;131:1105–9. doi: 10.1038/jid.2010.350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhang XJ, Huang W, Yang S, et al. Psoriasis genome-wide association study identifies susceptibility variants within LCE gene luster at 1q21. Nat Genet. 2009;41:205–10. doi: 10.1038/ng.310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Strange A, Capon F, Spencer CC, et al. A genome-wide association study identifies new psoriasis susceptibility loci and an interaction between HLA-C and ERAP1. Nat Genet. 2010;42:985–90. doi: 10.1038/ng.694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Samuelsson L, Stiller C, Friberg C, et al. Association analysis of cystatin A and zinc finger protein 148, two genes located at the psoriasis susceptibility locus PSORS5. J Invest Dermatol. 2004;122:1399–400. doi: 10.1046/j.0022-202X.2004.12604.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Vasilopoulos Y, Walters K, Cork MJ, et al. Association analysis of the skin barrier gene cystatin A at the PSORS5 locus in psoriatic patients: evidence for interaction between PSORS1 and PSORS5. Eur J Hum Genet. 2008;16:1002–9. doi: 10.1038/ejhg.2008.40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zeeuwen PL, van Vlijmen-Willems IM, Jansen BJ, et al. Cystatin M/E expression is restricted to differentiated epidermal keratinocytes and sweat glands: a new skin-specific proteinase inhibitor that is a target for cross-linking by transglutaminase. J Invest Dermatol. 2001;116:693–701. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1747.2001.01309.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cheng T, Tjabringa TS, van Vlijmen-Willems IM, et al. The cystatin M/E-controlled pathway of skin barrier formation: expression of its key components in psoriasis and atopic dermatitis. Br J Dermatol. 2009;161:252–64. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2009.09156.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]