Abstract

Background:

This study is based on people dying at home relying on the care of unpaid family carers. There is growing recognition of the central role that family carers play and the burdens that they bear, but knowledge gaps remain around how to best support them.

Aim:

The aim of this study is to review the literature relating to the perspectives of family carers providing support to a person dying at home.

Design:

A narrative literature review was chosen to provide an overview and synthesis of findings. The following search terms were used: caregiver, carer, ‘terminal care’, ‘supportive care’, ‘end of life care’, ‘palliative care’, ‘domiciliary care’ AND home AND death OR dying.

Data sources:

During April–May 2013, Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL), MEDLINE, PsycINFO, Pubmed, Cochrane Reviews and Citation Indexes were searched. Inclusion criteria were as follows: English language, empirical studies and literature reviews, adult carers, perspectives of family carers, articles focusing on family carers providing end-of-life care in the home and those published between 2000 and 2013.

Results:

A total of 28 studies were included. The overarching themes were family carers’ views on the impact of the home as a setting for end-of-life care, support that made a home death possible, family carer’s views on deficits and gaps in support and transformations to the social and emotional space of the home.

Conclusion:

Many studies focus on the support needs of people caring for a dying family member at home, but few studies have considered how the home space is affected. Given the increasing tendency for home deaths, greater understanding of the interplay of factors affecting family carers may help improve community services.

Keywords: family carers, review, palliative care, end of life care, terminal care, caregivers, home

What is already known about the topic?

The proportion of people dying at home is increasing.

It is difficult to gauge the exact number of family carers who provide care for people dying at home, but the Worldwide Palliative Care Alliance claims there are 9 million family carers worldwide.

Family carers need support to manage end-of-life care in the home.

What this paper adds?

The review’s examination of the recent literature provides an overview of evidence of family carers’ views about the impact on the home as a setting for end-of-life care and its transformation during the process.

The evidence suggests that a complex set of social and emotional factors are involved in providing end-of-life care in the home.

There is evidence of gaps and deficits in the support that family carers receive.

Implications for practice, theory or policy

Understanding the complexities of end-of-life care in the home for family carers could improve services.

Understanding the support needs of family carers in the home setting could improve services.

Introduction

Within Europe there are approximately 100 million family carers whose contribution to care is estimated to exceed financial expenditure on formal nursing services.1 Although it is difficult to gauge exactly how many are caring for a person near the end of life, figures for the United Kingdom indicate that the proportion of people dying at home is increasing.2 With this comes greater reliance on family carers to provide care for the dying person. National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) defines family carers as people with a close social and emotional bond, not just those related by kinship or marriage.3 Considering the ageing European population and that the majority of deaths occur in those over 65 years of age,4 there is a need to better understand the implications and experiences of people dying at home and their family carers. This article examines the available literature to provide a critical narrative review of what is known about these experiences and the perspectives of family carers providing support to a person dying at home.

Around 500,000 people die in England each year, and it is predicted that this will rise to 590,000 within the next 20 years.5 Between 2004 and 2011, the proportion of deaths occurring in the home increased from 18% to 22% (compared to a decrease in hospital deaths from 58% to 51%).2,5 However, a large discrepancy still remains between the actual proportion of people dying at home (22%) and those who wish to die at home (63%),6 suggesting that over 200,000 people each year do not die in the place of their choosing. As a result, end-of-life care policy continues to promote dying at home, but this is based on the assumption that family carers will be able and willing to provide care.

It is difficult to accurately estimate the number of family carers providing end-of-life care. There is no clear point at which a person is defined as entering the ‘end-of-life phase’.7 Of the 6.4 million unpaid family carers in the United Kingdom, approximately 500,000 are thought to be providing care to someone with a terminal illness.8 Identification of people with ‘terminal illnesses’ may not include those with long-term conditions, dementia and more general health and social care needs such as frailty. As a result, the number of actual family carers providing end-of-life care is likely to be much higher, especially when the wider network of family carers providing support is acknowledged (over 50% of hands-on care may be provided by extended family members).9 The number of family carers of people dying at home is therefore likely to be considerable. Each family carer is thought to save the UK economy around £18,000 per family carer per year,10 which means there are financial, as well as societal, incentives to ensuring that family carers are appropriately supported. The Carer’s Trust estimates that in England and Wales alone, 950,000 people aged over 65 years are family carers and that 65% of family carers aged 60–94 years have long-term health problems or a disability themselves.11

Research suggests that adults are increasingly dying at home and that family carers contribute substantially to the care given.9 While there is growing recognition of the central role that family carers play, knowledge gaps remain around how to best support them during the dying phase.9 There is also a need to better understand how the home setting for end-of-life care impacts people and their family carers, as there is some evidence to suggest that some people, especially those in late old age, may not regard home deaths as possible.12,13 When asked their views, people identified a number of potential practical and moral concerns regarding a home death, such as having no family carer, concerns about the quality of care that would be delivered and the feasibility of dying at home for those who live in poor housing conditions.14 Whether or not these concerns reflect the real-life experiences of most people dying at home and their family carers is unclear.

Aim

The aim of this article is to review the literature relating to the perspectives of family carers providing support to a person dying at home.

Methods

The narrative literature review methodology was chosen to provide an overview and synthesis of existing findings on the topic, using diverse sources and including a variety of research methods.15 Published research studies and literature reviews undertaken to explore the perspectives of family carers providing end-of-life care in the home were identified, collated and appraised. Searches were performed of the following databases during April and May 2013: CINAHL, MEDLINE, PsycINFO, Pubmed, Cochrane Reviews and Citation Indexes (through Web of Science). These databases were chosen because they include a wide range of journals, covering disciplines internationally across medicine, nursing, allied health and social science.

The following search terms were used: caregiver OR carer OR ‘terminal care’ OR ‘supportive care’ OR ‘end of life care’ OR ‘palliative care’ OR ‘domiciliary care’ AND home AND death OR dying. Appropriate wildcards were inserted to search for truncations in word endings where possible. As the review focused specifically on the perspectives of family carers, Medical Subject Heading (MeSH) terms were not used to determine the keywords to be searched for, because the clinical focus of MeSH as a methodology would potentially omit highly relevant studies. The search terms were purposefully kept broad to ensure a comprehensive search was completed, especially as terminology in this area includes caregivers, carers, family caregivers and informal carers, in addition to the term ‘family carers’. Grey literature searches were also completed by entering the search terms into the search engine ‘Google’. This resulted in one additional reference being sourced.

Articles were assessed against the inclusion and exclusion criteria listed in Table 1. Justifications for the inclusion and exclusion criteria include limited resources to undertake translations, empirical studies were seen as a proxy for quality rather than clinical opinion and the focus was on adult family carers rather than children who provide care to adults. We used the broad NICE definition3 of family carers as this has been widely cited. We focused on the recent literature to ensure that recommendations reflect current practice.

Table 1.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria.

| Inclusion criteria | Exclusion criteria |

|---|---|

| Written in the English language | Written language other than English |

| Empirical studies (qualitative and quantitative studies) and literature reviews | Editorials, comments and letters |

| International sources | Articles focusing on children and young (as carers and/or person receiving end-of-life care) |

| Adult family carers (above 18 years of age) | Formal and paid carers/carers who would not be defined as ‘family carers’ using NICE definition3 |

| Perspectives of family carers (as per the NICE definition3 | Articles focusing on family carers providing care to family members in a setting other than the home (e.g. acute or hospice setting) |

| Articles focusing on family carers providing end-of-life care in the home | Papers published prior to 2000 |

| Papers published between 2000 and 2013 |

NICE: National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence.

Results

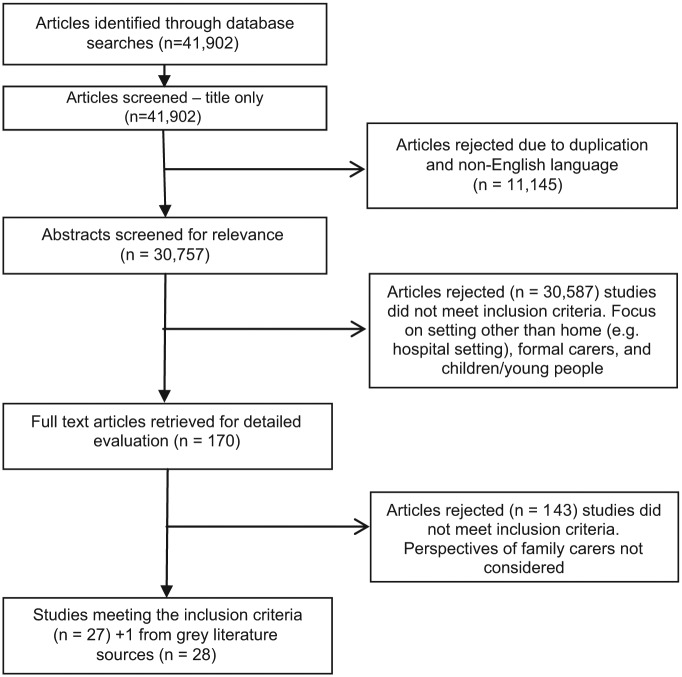

Studies identified from the search were selected systematically in the following way: consideration of the title, abstract and full text. The process is summarised in the PRISMA flowchart shown in Figure 1. Studies were included or excluded at each stage of the process, and each study was assessed by C.K. and overseen by M.T.

Figure 1.

Systematic selection process of articles.

The initial search of the identified databases using the listed search terms resulted in 41,902 studies. As the number of returns was so high, only an initial scan of the titles was carried out, and 11,145 studies were rejected due to duplications and non-English language use. Abstracts were then scanned, resulting in a further 30,587 studies being rejected because they did not meet the inclusion criteria (see Table 1). Another 143 studies were rejected following detailed evaluation of the full-text articles because the perspectives of family carers were not considered, meaning the inclusion criteria were not met.

A total of 27 studies from the database searches met the inclusion criteria. S.P. also identified one literature review (grey literature source) published in the United Kingdom that was relevant to the inclusion criteria, which was also included, giving a total of 28 studies.

The review included studies undertaken using a range of methodologies: 5 systematic reviews, 4 quantitative, 17 qualitative and 1 mixed-method designs. The studies are summarised in Table 2 (online supplementary). The number of studies from each of the following countries was as follows: Australia – 3, Canada – 3, Japan – 1, Netherlands – 1, Norway – 1, Sweden – 8, United Kingdom – 5, United States – 2 and reviews including studies from various countries – 3.

A content analysis was performed, which involved systematically reading each study and then listing the main themes identified in the results and discussion sections of the papers. A thematic synthesis was undertaken to group together similar themes under overarching categories. The following categories summarise the main findings from the studies reviewed:

Family carers’ views on the impact of the home as a setting for end-of-life care;

Practical and other types of support that made a home death possible;

Family carers’ views on deficits and gaps in support;

The transformations to the social and emotional space of the home during, and after, the process of caregiving.

Family carers’ views on the impact of the home as a setting for end-of-life care

Family carers identified both positive and negative meanings associated with the experience of providing palliative care at home. One of the main benefits of being in the home setting was the ability to continue with normal life as much as possible.16–20 Normal life was engendered by different things. Some family carers described their relationship with the dying person20,21 and the routine of day-to-day home life.18,21 Others felt their ability to continue with hobbies, and work patterns were important.19

For some family carers, a home death facilitated bond development with the dying person, for example, adult children spent more time with a parent than they had for many years.20 Family carers also felt they were able to make a better assessment of the patient’s comfort, as a result of spending long periods of time together in the private home, something that may be restricted in hospital settings, due to visiting hours and open ward environments.18 The home is a familiar environment and helps family carers and patients to feel more secure.22 Family carers felt they were more in control when they were able to define routines, such as meal times and visiting times.21 Family carers also felt the home setting allowed them to spend more time with family and friends,22 avoid stressful separations22 and was helpful in ‘distracting’ the patient at times to counteract a sense of helplessness.18 The ability to continue previous activities may decrease the family carer’s vulnerability and protect against fatigue and burnout.19 At the actual point of death, the home environment was perceived as helping to provide a sense of peace and dignity.20

Maintenance of normality was perceived as supporting a positive experience of a home death for family carers; however the burden of caring was identified as being a major contributing factor towards experiencing the dying process negatively.17,19,23 Burden was seen to be the result of feeling homebound,23 isolated17,23 and sleep deprived.23–25 Women felt homebound to a higher degree than men.23 For family carers, feelings of togetherness with the dying person were in conflict with a perception of isolation from the outside world, especially when family carers were alone with the burden of responsibility that came from being the only person there to meet care requirements.17,26 Isolation was also felt when the contribution made by family carers was not acknowledged by formal paid carers.17,27

The burden of care resulted in many family carers experiencing a range of feelings and emotions including fatigue, stress, distress at witnessing disease progression, frustration and uncertainty.16,28

Practical and other types of support that made a home death possible

There has been a considerable amount of research into the needs of family carers providing end-of-life care.8 A number of systematic reviews have concluded that, primarily, what helps family carers is being part of a good formal paid care team.28–30 Across a range of studies, a good care team is defined as one having a positive attitude, providing holistic ‘around the clock’ patient care, giving clear, timely information about the patient’s condition and acknowledging the significance of the family carer’s role.24,26–29,31 These factors are deemed to be important regardless of the care setting.

One factor that is specific to the home setting, that is also deemed to be important to family carers, is the ability to manage symptoms and administer pain relief medication.28,32 While acknowledging the security and ethical issues related to the management of certain medications,32 family carers willingly assumed responsibility for treatment because it meant they could provide immediate symptom relief.28,32 Family carers who manage medication require support to know what to monitor, how to interpret symptoms accurately and when to inform a professional;33 otherwise the burden of care may be perceived as being higher.26

Family carers who provide support to relatives at the end of life need to be prepared for their caring role.24 The majority of family carers felt that professional care was largely accessible and responsive to patients’ changing needs.34 Although the support given made a home death possible, for some groups of family carers, support may not be fully meeting their specific requirements. For example, family carers of older people with life-limiting illnesses may require nursing guidance earlier than it is usually provided.25 Bangladeshi family carers living in the United Kingdom felt that, in addition to the demands and stresses caused by their relatives’ symptoms and the knowledge that they were dying, they experienced communication barriers and isolation.35

Family carers’ views on deficits and gaps in support

Research indicates that there are still a number of unmet needs that impact the health and wellbeing of family carers, which impedes their ability to care in the way they would want.30,31,34 In a systematic review,30 research consistently highlighted the lack of practical support, often related to inadequate information exchange for family carers providing end-of-life care to patients with advanced cancer. Communication about practical support was also an issue, for example, family carers did not know who was coming, how often and when.34 These deficits typically manifest in relatives adopting a ‘trial and error’ approach to palliative care,30 and extended family, friends and neighbours are in turn relied upon to moderate the stressful effects of caregiving.36

Gaps in support were not only linked to the care of the dying person but also to the welfare of the family carers themselves, with some family carers potentially having more unmet needs than the patients they are caring for.16 Proot et al.19 identified three dimensions of support that family carers required from professional home care: instrumental (practical assistance), emotional (relieving the care burden and allowing family carers to maintain own activities) and information (frequent information about prognosis and expected complications). It was often the emotional support that family carers perceived to be missing.19,23 For older carers however, findings suggest that all three dimensions of support may be required at different times and in different ways.19,37 Many family carers are themselves frail and elderly, which can lead to the breakdown of ability to care28 and participate in hands-on care, such as feeding and bathing.37 When considering people with dementia in particular, cognitive impairment makes the practical aspects of providing care all the more challenging, as levels of pain and discomfort are not easily communicated.38

Ultimately, when considering family carers’ views on what gaps exist, a range of needs are identified including personal, social and spiritual support, as well as use of outside resources, access and knowledge.16 Therefore, it is important to acknowledge that the links family carers form with outside care agencies may define perceptions on how care needs are, or are not, being met. It has been suggested that family carers felt left out and had feelings of powerlessness when they did not manage to establish a relationship with the healthcare professionals.31

The transformations to the social and emotional space of the home during, and after, the process of caregiving

Family carers felt that the home environment had been altered, privacy had been lost and the meaning of the home had changed during the process of providing care to a dying person.22 Family carers often identified two major transformations to the social and emotional space of the home: adaptation and decreasing personal space.16,22,28,39–41

Adaptation was felt to be part of accepting care within the home.16,39 The home was seen as being transformed into a hospital environment.16 Unfamiliar items, such as hoists, commodes and medication, became part of daily routine.28 Family carers experienced their home as a ‘house with a swinging door’16 and were concerned by the number of healthcare professionals entering the home during the day and night.40,41

The home became a site for healthcare provision, and in turn, home and family relationships changed for family carers, who felt their personal space decreased.39 The home space was changed because family carers were found to put the needs of the ill family member before their own,39 and the critically ill person was confined to bed, for example, the living room became the sick room, as well as the bedroom, for spouses.40

A review of qualitative research concluded that the home became socially isolating.42 Adapting to the ill person contributed to a sense of isolation from life and made it difficult for the family carer to leave the home.39 There was a realisation that there was no space for their own living, and they had to adapt to losing privacy and time for their own interests.16 Family carers perceived stressful situations that they could not escape from either physically or mentally,19,39 and as the disease progressed, the home became institutionalised.40 Family carers reported that they felt ‘tied to the sick bed’, which meant that they neglected their own needs. However, they also felt they could have provided better care if they had had the chance to take better care of themselves.27

Transformations to the home space can be long lasting. Feelings of isolation can remain following the death of a family member; however, reorganising the structure of everyday life (e.g. incorporating new routines and meal times) can support grief management,40 and for some family carers, there was no regret that their family member was cared for and died at home.27 Having the home as the place where a close person has died added to the perceived comfort they felt.22

Discussion

This literature review has identified four themes from family carers’ perspectives on providing end-of-life care in the home. Many of these themes appear to be interconnected, that is, good holistic care helps family carers to maintain a normal life by reducing the burden of care, and in turn, this helps to reduce feelings of isolation and the sense of decreasing personal space.

For many family carers, there were no regrets that their family member received palliative care at home. An important aspect was the ability to maintain a normal life for as long as possible.27 This may be a particularly important consideration for family carers of people with non-malignant illnesses where the duration of care can span years.25 The decline in the person’s physical and mental health can be prolonged, and events are more likely to occur or occur more often, for example, the patient falling. Many life-threatening episodes may be experienced, from which the person recovers.25 For people with dementia in their last year of life, family carers (with a mean age of 65) reported spending at least 46 h per week assisting with daily living activities. More than half the family carers felt they were on duty 24 h a day, and many family carers had to give up work or reduce their working hours to provide care.38 As a result, family carers may lose the ability to maintain a normal life over a prolonged period of time.

Recent Cochrane reviews concluded that supportive interventions may help reduce family carers’ psychological distress43 and receiving expert home palliative care doubles the odds of dying at home.44 The end-of-life phase is difficult to define for many people however, and so holistic and dignified palliative care may not occur when required in the home setting. Ultimately, the support required from external agencies will differ between family carers,42 but there is evidence that carers who are over 65 years of age are more likely to require a higher level of support.19,37

While this review has highlighted family carers’ perceived benefits of a home death, it should be considered that these positive aspects have also been identified in hospital and hospice settings.20 A number of family carers felt the home space was changed as a result of being the setting for end-of-life care. The concept of the home to deliver hospice care has been discussed in the geographical literature.45,46 Contemporary living has resulted in more people living to an older age alone in rented accommodation and smaller apartments.45,46 Families tend to have greater geographical mobility and so are not necessarily physically close enough to support end-of-life care to a family member. As a result, the home may not practically provide an appropriate setting for end-of-life care. Privacy, accessibility and comfort may not be achievable,45 yet UK policy continues to be based on the assumption that families will provide care in the home.44

The meaning of a home death may differ between socio-demographic groups.44 Family carers from Bangladeshi communities living in the United Kingdom experienced communication barriers and anxieties regarding visas and housing (e.g. it was sometimes difficult for family to visit a dying relative from another country).35 For others, dying at home may not be the house in which they would normally reside, but can mean the country in which they were originally born.28

Strengths and weaknesses

The methods used in carrying out the search and inclusion/exclusion criteria have been described in detail to demonstrate how bias was minimised where possible. The papers reviewed were of diverse methodology and variable quality, which meant that using a standardised critical appraisal tool was not possible. Only research published in English was reviewed. As a result, non-English studies are missing. However, the studies included in this review did not reference any foreign-language studies. There was also a limited review of the grey literature, which may have resulted in relevant outputs being omitted.

Further research

People are increasingly required to offer care for a family member in the home at the end of life, often in situations where there is a long gradual process of decline.8,28 The majority of studies reviewed included the perspectives of family carers of patients who are dying in later life; however, there was little research that looked specifically at the perspective of older family carers separately,31 which means specific support needs may not be recognised. The majority of studies included in this review focused on cancer patients receiving palliative care at home. There are still very few studies that consider family carers of patients with other conditions, such as dementia. The intensity and duration of care may be greater in some cases for people dying at home of non-malignant conditions, and as the prevalence of people dying at home with these conditions increases, family carers’ needs in these circumstances need to be more clearly understood.

There is a general need for further research to focus on the impact of providing end-of-life care on family carers in the home environment.23 In addition, good quality qualitative studies exploring the meaning of ‘home’ across the caregiving process and whether family carers experience a change in their attachment to home warrants further study.44 Further research to investigate the architectural and spatial implications of palliative care in the home environment would also be useful.43

Implications for practice

Research has indicated that home-based family carers require advice and support to undertake practical nursing; however, this often remains unfulfilled.30 As a minimum, family carers should be educated and trained in medication management and symptom control.30 Early education on the practical, technical and emotional aspects of providing end-of-life care may be required for those caring for people with dementia or non-malignant disease when the trajectory of dying is more uncertain.42

In a home setting, the family carer is often viewed as a co-worker and as such may not be identified as having care needs in their own right.8 Professionals and providers need to ‘think family’ and consider how support for family carers can impact the care of the patient.28 This is particularly important for people, where family carers may themselves have disabilities and illnesses as a result of ageing.

When previous habits could not be continued and the ability to maintain everyday routines was lost, family carers felt they suffered as a result.18 As the severity of illness increases, changes in everyday life will inevitably occur; however, support can focus on timing care visits around family routines and ensuring that aids to support normal activity are available.18 The family themselves should define how normal life can be best preserved.18

Conclusion

How family carers perceive their experience of providing end-of-life care in the home setting appears to depend upon a complex interplay between the resources that family carers have available to them, both pre-existing and provided by outside agencies, family and friends, technical support (such as medication and equipment), informational support and how family carers perceive these resources (in terms of supporting them to maintain normalcy wherever possible). The impact of available resources on minimising the burden of care and allowing families to maintain normal life as much as possible are key factors that influence family carers’ perceptions of the dying process.

While there is a wealth of studies focusing on the support needs and gaps of caring for a dying family member at home, few studies have considered how the home space is affected. There was an emerging consensus that providing care at home was beneficial for a number of reasons, but this seemed to be at odds with the small number of studies indicating that the home space was negatively affected. In addition, it is not possible to determine from the current literature whether or not the positive aspects of a home death identified are transferable specifically to people, whose family carers may be older and have health needs themselves. Therefore, further research is required to explore the issues faced by family members caring for a dying person at home and the impact this has on the home space.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the ‘Unpacking the Home’ research team: Christine Milligan (co-applicant), David Seamark (co-applicant), Carol Thomas (co-applicant), Sarah Brearley (co-applicant), Xu Wang (co-applicant), Susan Blake (researcher), Jill Robinson (service user) and Janet Ross Mills (service user).

Footnotes

Declaration of conflicting interests: The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Funding: This review received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

References

- 1. Eurocarers Factsheet. Family care in Europe. The contribution of carers to long-term care, especially for older people. Eurocarers, http://www.eurocarers.org/userfiles/file/factsheets/FactsheetEurocarers.pdf (2009, accessed 4 April 2014).

- 2. Department of Health. End of life care strategy: fourth annual report. London: Department of Health, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 3. National Institute for Clinical Excellence. Guidance on cancer services: improving supportive and palliative care for adults with cancer – the manual. London: National Institute for Clinical Excellence, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Seymour J, Witherspoon R, Gott M, et al. Dying in older age: end-of-life care. Bristol: Policy Press, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Department of Health. End of life care strategy: promoting high quality care for adults at the end of life. London: Department of Health, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Gomes B, Calanzani N, Higginson IJ. Local preferences and place of death in regions within England 2010. London: Cicely Saunders International, http://www.csi.kcl.ac.uk/files/Local%20preferences%20and%20place%20of%20death%20in%20regions%20within%20England.pdf (2011, accessed 4 April 2014). [Google Scholar]

- 7. Marie Curie Cancer Care. Committed to carers: supporting carers of people at the end of life. London: Marie Curie Cancer Care, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Grande G, Stajduhar K, Aoun S, et al. Supporting lay carers in end of life care: current gaps and future priorities. Palliat Med 2009; 23(4): 339–344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Burns CM, Abernethy AP, Dal Grande E, et al. Uncovering an invisible network of direct caregivers at the end of life: a population study. Palliat Med 2013; 27(7): 608–615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Buckner L, Yeandle S. Valuing carers 2011 – calculating the value of carers’ support. London: Carers UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 11. The Princess Royal Trust for Carers. Always on call, always concerned: a survey of the experiences of older carers. Woodford Green: The Princess Royal Trust for Carers, http://www.carers.org/sites/default/files/always_on_call_always_concerned.pdf (2011, accessed 4 April 2014). [Google Scholar]

- 12. Gott M, Seymour JE, Bellamy G, et al. How important is dying at home to the ‘good death’? Findings from a qualitative study with older people. Palliat Med 2004; 18: 460–467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Thomas C, Morris SM, Harman JC. Companions through cancer: the care given by informal carers in cancer contexts. Soc Sci Med 2002; 54: 529–544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Gott M, Seymour J, Bellamy G, et al. Older people’s views about home as a place of care at the end of life. Palliat Med 2004; 18(5): 460–467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Dixon-Woods M, Agarwal S, Jones D, et al. Synthesising qualitative and quantitative evidence: a review of possible methods. J Health Serv Res Policy 2005; 10(1): 45–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Appelin G, Brobäck G, Berterö C. A comprehensive picture of palliative care at home from the people involved. Eur J Oncol Nurs 2005; 9(4): 315–324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Milberg A, Strang P. What to do when ‘there is nothing more to do’? A study within a salutogenic framework of family members’ experience of palliative home care staff. Psychooncology 2007; 16(8): 741–751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Milberg A, Strang P. Meaningfulness in palliative home care: an interview study of dying cancer patients’ next of kin. Palliat Support Care 2003; 1(2): 171–180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Proot IM, Abu-Saad HH, Crebolder HFJM, et al. Vulnerability of family caregivers in terminal palliative care at home; balancing between burden and capacity. Scand J Caring Sci 2003; 17(2): 113–121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Wong WKT, Ussher J. Bereaved informal cancer carers making sense of their palliative care experiences at home. Health Soc Care Community 2009; 17(3): 274–282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Stajduhar KI, Davies B. Variations in and factors influencing family members’ decisions for palliative home care. Palliat Med 2005; 19(1): 21–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Milberg A, Strang P, Carlsson M, et al. Advanced palliative home care: next-of-kin’s perspective. J Palliat Med 2003; 6(5): 749–756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Rollison B, Carlsson M. Evaluation of advanced home care (AHC). The next-of-kin’s experiences. Eur J Oncology Nurs 2002; 6(2): 100–106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Harding R, Epiphaniou E, Hamilton D, et al. What are the perceived needs and challenges of informal caregivers in home cancer palliative care? Qualitative data to construct a feasible psycho-educational intervention. Support Care Cancer 2012; 20(9): 1975–1982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Phillips LR, Reed PG. Into the Abyss of someone else’s dying: the voice of the end-of-life caregiver. Clin Nurs Res 2009; 18(1): 80–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Ishii Y, Miyashita M, Sato K, et al. A family’s difficulties in caring for a cancer patient at the end of life at home in Japan. J Pain Symptom Manage 2012; 44(4): 552–562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Hunstad I, Foelsvik Svindseth M. Challenges in home-based palliative care in Norway: a qualitative study of spouses’ experiences. Int J Palliat Nurs 2011; 17(8): 398–404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Social Care Institute for Excellence. Dying well at home: research evidence, http://www.scie.org.uk/publications/guides/guide48/files/guide48_researchevidence.pdf (2013, accessed 14 April 2014).

- 29. Andershed B. Relatives in end-of-life care – part 1: a systematic review of the literature the five last years, January 1999–February 2004. J Clin Nurs 2006; 15(9): 1158–1169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Bee PE, Barnes P, Luker K. A systematic review of informal caregivers’ needs in providing home-based end-of-life care to people with cancer. J Clin Nurs 2009; 18(10): 1379–1393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Linderholm M, Friedrichsen M. A desire to be seen: family caregivers’ experiences of their caring role in palliative home care. Cancer Nurs 2010; 33(1): 28–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Anderson BA, Kralik D. Palliative care at home: carers and medication management. Palliat Support Care 2008; 6(4): 349–356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Armes PJ, Addington-Hall JM. Perspectives on symptom control in patients receiving community palliative care. Palliat Med 2003; 17(7): 608–615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Brazil K, Bainbridge D, Ploeg J, et al. Family caregiver views on patient-centred care at the end of life. Scand J Caring Sci 2012; 26(3): 513–518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Somerville J. Palliative care: the experience of informal carers within the Bangladeshi community. Int J Palliat Nurs 2001; 7(5): 240–247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Brazil K, Bainbridge D, Rodriguez C. The stress process in palliative care: a qualitative study on informal caregiving and its implication for the delivery of care. Am J Hosp Palliat Care 2010; 27(2): 111–116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. McNamara B, Rosenwax L. Which carers of family members at the end of life need more support from health services and why? Soc Sci Med 2010; 70(7): 1035–1041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Schulz R, Mendelsohn AB, Haley WE, et al. End-of-life care and the effects of bereavement on family caregivers of persons with dementia. N Engl J Med 2003; 349(20): 1936–1942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Carlander I, Sahlberg-Blom E, Hellström I, et al. The modified self: family caregivers’ experiences of caring for a dying family member at home. J Clin Nurs 2011; 20(7–8): 1097–1105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Fisker T, Strandmark M. Experiences of surviving spouse of terminally ill spouse: a phenomenological study of an altruistic perspective. Scand J Caring Sci 2007; 21(2): 274–281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Stajduhar KI. Examining the perspectives of family members involved in the delivery of palliative care at home. J Palliat Care 2003; 19(1): 27–35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Funk L, Stajduhar K, Toye C, et al. Part 2: home-based family caregiving at the end of life: a comprehensive review of published qualitative research (1998–2008). Palliat Med 2010; 24(6): 594–607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Candy B, Jones L, Drake R, et al. Interventions for supporting informal caregivers of patients in the terminal phase of a disease (Review). Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2011; 15(6): CD007617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Gomes B, Calanzani N, Curiale V, et al. Effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of home palliative care services for adults with advanced illness and their caregivers. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2013; 66: CD007760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Williams A. Changing geographies of care: employing the concept of therapeutic landscapes as a framework in examining home space. Soc Sci Med 2002; 55(1): 141–154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. McGann S. Spatial practices and the home as hospice. Australas Med J 2011; 4(9): 495–499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.