Abstract

AIM: To examine whether the fasting levels of serum gastrin-17 (G-17) are lower in Barrett's esophagus (BE) patients than in non-Barrett controls.

METHODS: Nineteen patients with BE (presenting with a tubular segment ≥2 cm long in lower esophagus and intestinal metaplasia of incomplete type ("pecialized columnar epithelium") in endoscopic biopsies from the tubular segment below the squamocolumnar junction were collected prospectively from outpatients referred to diagnostic gastroscopy. The controls comprised 199 prospectively collected dyspeptic outpatients without BE or any endoscopically visible lesions in the upper GI tract. Fasting levels of serum G-17 (G-17fast) were assayed with an EIA test using a Mab highly specific to amidated G-17. None of the patients and controls received therapy with PPIs or other antisecretory agents.

RESULTS: The mean and median levels of G-17fast in serum were significantly lower (P = 0.001) in BE patients than in controls. The positive likelihood ratios (LR+) of low G-17fast to predict BE in the whole study population at G-17fast levels <0.5, <1, or <1.5 pmol/L were 3.5, 3.0, and 2.8, respectively. Among patients and controls with healthy stomach mucosa, the LR+ were 5.6, 3.8, and 2.6, respectively. In the whole study population, serum G-17 was below 2 pmol/L in 15 of 19 BE patients (79%). The corresponding prevalence was 66 of 199 (33%) in controls (P<0.001). The G-17fast was 5 pmol/L or more in only one of the 19 BE patients (5%). In controls, 76 of the 199 patients (38%) had such high serum G-17fast levels (P<0.01).

CONCLUSION: Serum levels of G-17fast tend to be lower in native patients with BE than in healthy controls.

Keywords: Gastrin-17, Barrett’s esophagus, Chronic gastritis, Atrophic gastritis, Diagnostics

INTRODUCTION

High intragastric acidity inhibits the release of gastrin into circulation from antral G cells, and conversely, low acidity and high intragastric pH enhance this release[1,2]. Amidated gastrin-17 (G-17) is the biologically active main gastrin fragment, and G-17 is a gastrin compound secreted nearly entirely from the antral G cells[3-5]. It is conceivable that fasting levels of G-17 (G17fast) in serum or plasma reflect indirectly the intragastric acidity. Correspondingly, it is conceivable that low serum levels of G-17 occur particularly in patients with acid-related diseases.

Gastroesophageal reflux disease is one of the most important acid-related diseases[6]. Patients with Barrett’s esophagus (BE) are a subgroup of reflux patients in whom the refluxed acid gastric juice is a factor causing mucosal damages in the lower esophagus, and at the esophagogastric junction[7-9]. Some studies indicate that the prevalence of BE ranges from 0.5% to 5.0% in patients undergoing upper-GI endoscopy for dyspepsia, and from 12% to 15% in patients with gastroesophageal reflux disease and reflux symptoms[10-13].

In the present study, we investigated whether the serum levels of G-17 are lower in patients with BE than in non-BE controls.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patient and control series were collected prospectively in 2002 in Helsinki University Central Hospital (HUCH), Jorvi Hospital, Espoo, Finland, from patients who were referred to diagnostic gastroscopy for dyspeptic or reflux-type symptoms.

Patient series

The patient series consisted of 19 subjects with a BE diagnosed by endoscopy and histology. All had a Barrett's segment 2 cmor more in length in the lower columnar, tubular esophagus. Of the available 19 patients, 14 were males and 5 females. The mean age was 6012 years. Three of the nineteen BE patients (16%) had Helicobacter pylori (H pylori)-related gastritis. In one of these three patients, gastritis was strongly antrum dominant, and this patient showed moderate atrophy and intestinal metaplasia in the antrum. The histopathology was evaluated by biopsies from antrum and corpus (at least two biopsies from each site), and by the principles of the updated Sydney System. The biopsy specimens were stained with HE and Alcian blue (pH 2.5)-PAS methods and modified Giemsa for H pylori.

Control series

The control series consisted of 199 patients without any visible endoscopic lesions in the upper GI tract. Of the 199 patients, 71 were males and 128 females. The mean age was 5415 years. Altogether, 94 patients (47%) had chronic H pylori-related or autoimmune chronic gastritis, or atrophic gastritis. The rest had normal and healthy gastric mucosa in gastric biopsies (no chronic gastritis, no H pylori, no intestinal metaplasia or atrophy). Of the total number of patients with chronic gastritis, 48 had atrophic gastritis of some grade and type. Advanced (moderate or severe) atrophic gastritis in corpus was found in 23 patients.

Inclusions and exclusions

A patient in the Barrett series was included if he/she had a segment of Barrett’s mucosa 2 cm or more in length that was verified by endoscopy and histology of the biopsies taken below the squamocolumnar junction (z-line). The biopsies had to show the presence of intestinal metaplasia of incomplete type ("specialized columnar epithelium"), i.e. intestinal metaplasia of type II or III in the Alcian blue (pH 2.5)-PAS-stained sections[14]. In incomplete type of intestinal metaplasia, both goblet cells and columnar epithelium between the goblet cells showed secretory mucins that were stained blue with Alcian blue (pH 2.5)-PAS.

The following patients were excluded: patients with a short segment Barrett (the presence of "specialized columnar epithelium" in biopsies from a segment that is less than 2 cm long); patients with erosive esophagitis, ulcers, or polyps, or those with any endoscopically visible local lesions in stomach or esophagus.

Use of PPIs

Patients and controls with a long-term use of PPIs were excluded from the study, and none of the patients or controls was recorded having used PPI at the time of the diagnosis (information obtained from the patient at endoscopy). Thus, the present BE patients represented the native cases of dyspeptic subjects in whom BE was accidentally diagnosed in a diagnostic endoscopy, and in the subjects who did not receive any effective treatment.

Endoscopy

Diagnostic upper-GI endoscopy was done in all patients and controls. In both patient and control series, two groups were formed: the whole study population that included all patients and controls, and a subgroup of patients and controls in which the histology showed normal and healthy gastric mucosa (updated Sydney criteria) in both antrum and corpus biopsies (no gastritis, no atrophy, no intestinal metaplasia, nor H pylori). In the Barrett series, 16 of 19 patients (84%) were classified into the subgroup 2 (subjects with healthy and normal gastric mucosa). In controls, 105 of 199 (53%) subjects were classified into the subgroup 2.

Assay of amidated gastrin-17

G-17 was determined using specific EIA tests (G-17 EIA test kit Cat. No. 601 030, Biohit Plc, Helsinki, Finland) performed in batches of 40 samples on a microwell plate according to the instructions of the manufacturer. The EIA technique was based on measuring the absorbance after a peroxidation reaction at 450 nm. Between the reaction steps the plates were washed in a BW50 microplate strip washer (Biohit Plc, Helsinki, Finland). The absorbances were measured using a microplate reader (BP800 Microplate Reader, Biohit Plc, Helsinki, Finland). For determination of G-17 values, a 2nd?order fit on standard concentrations was used to interpolate/extrapolate unknown sample concentrations automatically with the help of the BP800 in-built software (Biohit Plc, Helsinki, Finland).

The monoclonal antibody (Mab) of G-17 in the EIA tests was highly specific. The G-17 antibody used detected only amidated G-17, but no other gastrin molecules or fragments (e.g., glycine extended G-17, a kind gift from Prof. Jens F Rehfeld, Copenhagen, Denmark; human synthetic gastrin-34, G-5024, Sigma; human synthetic gastrin-13, G-0267, Sigma; or cholecystokinin fragment 26-33 amide, C-2901, Sigma) were detected. In immunohistochemistry (formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded specimens: dilutions up to 10 000), the G-17 antibody stained only antral G cells and glands, not other cells or tissues in stomach, duodenum, small or large bowel, or pancreas. The G-17 EIA results correlated well with those of the G-17 RIA (by the courtesy of Prof. Jens F Rehfeld and Dr. Jens-Peter Gotze, Copenhagen, Denmark).

The G-17 assays from serum samples were done first after an overnight fast (G-17fast) and 20 min after a drink of a glass of a protein-rich juice (Biohit Plc, Helsinki, Finland) in which the protein content corresponded to that in an ordinary beef.

Specificity of G-17 antibody

The specificity of the antibody to G-17 secreted from antral G cells alone has been recently verified[15]. The G-17 assay measured only amidated G-17, and not other gastrin fragments.

Invasive and non-invasive tests for gastritis and atrophic gastritis

In addition to endoscopy and histology, the patient and control series were also classified into those with normal and healthy stomach or into those with non-atrophic or atrophic gastritis by serological tests which applied assays of H pylori antibodies, pepsinogens I (PGI) and II (PGII) and postprandial G-17 in serum (GastroPanel, Biohit Plc, Helsinki, Finland). The patients without H pylori antibodies and with PGI 50 microg/L, or more or above, were considered to have normal and healthy stomach mucosae.

Ethics

The study was approved by the Ethical Committee of the Helsinki District University Hospital (HUCH), Helsinki, Finland. The purpose of the study was explained to all patients before taking blood samples, and all patients signed a written consent before enrolment into the study.

Statistical analysis

Non-parametric tests (Wilcoxon-Mann-Whitney test; c2test; SPSS 10.1 Software) were used in the calculations of the significance between the groups. In order to examine the clinical value of low serum G-17 in the diagnosis of BE, the likelihood ratio (LR+) of the positive test result (low G-17fast or G-17prand) between the cases and controls was calculated at arbitrary cut-off levels of G-17. The LR+ indicates a factor by which the pre-test odds of BE has to be multiplied to obtain the post-test odds and, further, the post-test probability of the disease.

RESULTS

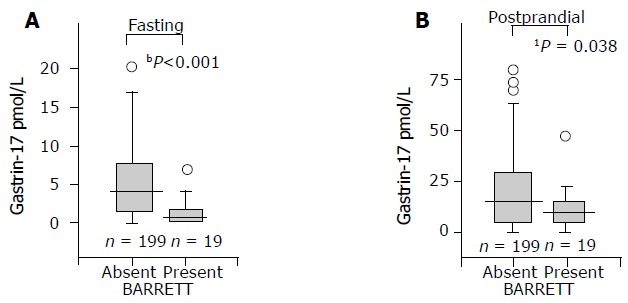

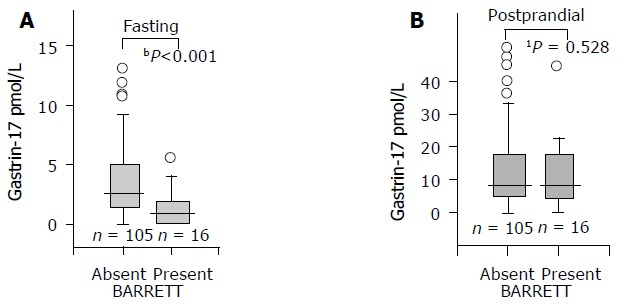

The mean and median values of serum G-17fast were significantly lower in patients with long-segment BE than in controls. This was the case both in males and females, or when the analysis was done in the whole study population (all patients and controls), or if the analysis was limited to subgroups of patients and controls with histologically normal and healthy gastric mucosa. The results in the whole study population and among those with healthy stomach mucosa are shown in Figures 1 and 2 in a box-plot form.

Figure 1.

Fasting (A) and postprandial (B) serum G-17 levels in patients with or without long-segment BE in the whole study population. A box plot presentation. The boxes show the central 50% of the cases. The length of the box shows the range within which the center 50% of the values fell. The whiskers show the range of values that fall within 1.5 difference of the values of median from the two hinges of the box. Differences: a: P<0.001; b: P=0.038; non-parametric test (MannWhitney U). To make the figure clear, the very most extreme outliers are not shown in the pictures.

In contrast to G-17fast, the serum levels of postprandial G-17 (G-17prand) were significantly lower in BE patients than in controls in the whole study population only but not in the subjects with normal and healthy stomach mucosae (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Fasting (A) and postprandial (B) serum G-17 levels in patients with or without long-segment BE among patients and controls with normal and healthy stomach mucosae (no gastritis, no H. pylori, and no atrophy). A box plot presentation (see Figure 1). Differences: a: P<0.001; b: P=0.528; non-parametric test (MannWhitney U). To make the figure clear, the very most extreme outliers are not shown in the pictures.

The positive LR+ of low serum G-17 to predict odds of BE in the whole study population below the arbitrary cut-off levels of G-17fast are presented in Table 1. The corresponding results in the subgroups of cases and controls with histologically normal, healthy gastric mucosa are shown in Table 2. It appears that the LR+ gradually increased with a decreasing concentration of G-17fast. The sensitivity and specificity of low serum G-17fast (<1 pmol/L) to indicate BE in the whole study population were 47% and 89%, respectively.

Table 1.

LR+ of low serum level of fasting G-17 in whole study population

| G-17fast pmol/L | Barrett n | Controls n | LR+(95%CI) |

| <0.5 | 7 | 21 | 3.5 (1.39.3) |

| <1 | 9 | 31 | 3.0 (1.37.3) |

| <1.5 | 13 | 48 | 2.8 (1.36.1) |

| <2 | 15 | 66 | 2.4 (1.14.9) |

| <3 | 17 | 89 | 2.0 (1.04.0) |

| <5 | 18 | 123 | 1.5 (0.83.0) |

| All | 19 | 199 | 1 |

Table 2.

LR+ of low serum level of fasting G-17 in patients and controls (males and females) with normal and healthy gastric mucosae (histology)

| G-17fast pmol/L | Barrett n | Controls n | LR+(95%CI) |

| <0.5 | 6 | 7 | 5.6 (1.719) |

| <1 | 7 | 12 | 3.8 (1.311) |

| <1.5 | 10 | 25 | 2.6 (1.16.5) |

| <2 | 12 | 42 | 1.9 (0.84.3) |

| <3 | 14 | 61 | 1.5 (0.73.3) |

| <5 | 15 | 79 | 1.2 (0.62.7) |

| All | 16 | 105 | 1 |

The study population was also classified into those with normal and healthy stomach mucosae (16 BE patients and 108 controls) and those with gastritis or atrophic gastritis (3 BE patients and 91 controls) by applying the serological tests (GastroPanel, Biohit Plc, Helsinki, Finland). By these tests, the stomach mucosa was healthy when H pylori antibodies were not present and the serum pepsinogen I was 50 mg/L, or more. Among the patients diagnosed to have a healthy stomach mucosa by these tests, the LR+s of BE are presented in Table 3. The sensitivity and specificity of low serum G-17fast (<1 pmol/L) to indicate BE were 50% and 82%, respectively, and at the cut-off level <2 pmol/L 81% and 55%, respectively. The corresponding overall accuracies were 77% and 55%, respectively.

Table 3.

LR+ of low serum level of fasting G-17 in patients and controls with healthy gastric mucosa, no H. pylori antibodies and serum pepsinogen I 50 mg/L

| G-17fast pmol/L | Barrett n | Controls n | LR+(95%CI) |

| <0.5 | 6 | 13 | 3.1 (1.09.4) |

| <1 | 8 | 19 | 2.8 (1.17.6) |

| <1.5 | 11 | 34 | 2.2 (0.95.1) |

| <2 | 13 | 49 | 1.8 (0.84.0) |

| <3 | 15 | 65 | 1.6 (0.73.4) |

| <5 | 15 | 81 | 1.3 (0.62.7) |

| All | 16 | 108 | 1 |

In the whole study population, the G-17fast was very low (<0.5 pmol/L) in 7 of the 19 BE (37%) and 15 of the 199 controls (8%). Correspondingly, the G-17fast was lower than 2 pmol/L in 15 of 19 BE patients (79%) and in 66 of 199 controls (33%,P<0.001; c2). The G-17fast was 5 pmol/L or more in 1 of 19 BE patients (5%) but in 76 of 199 controls (38%, P<0.01; c2). In this BE patient, the G-17fast was 5.4 pmol/L.

Three BE patients had H pylori-positive chronic gastritis in the biopsy specimens from antrum and corpus. In one of these patients, gastritis was strongly antrum dominant and showed intestinal metaplasia of moderate grade in the antral biopsy specimens. In spite of the presence of gastritis, all three of these BE patients had a low serum level of G-17fast (0.02, 0.6, and 1.4 pmol/L).

Among controls with normal and healthy stomach mucosae (antrum and corpus mucosae were histologically healthy), age and serum G-17fast did not correlate (Pearson correlation 0.05; P = 0.587); neither was there any difference in the serum G-17fast between males and females (meanSD: 4.75.7 and 4.15.4 pmol/L, respectively).

DISCUSSION

The present data indicate that the mean and median levels of serum G-17fast tend to be lower in patients with“native” (without previous or ongoing medication, nor previous knowledge of the disease) BE than in controls among outpatients referred to diagnostic endoscopy for dyspeptic symptoms. The BE is associated inversely with the serum level of G-17fast.

An inverse association between the likelihood of BE and serum level of G-17 was seen among the subjects with healthy stomach mucosa (normal gastric histology) and in the whole study population including subjects with gastritis and H pyloriinfection. Several earlier studies have shown that gastric inflammation (gastritis) tends to raise the serum levels of gastrin and other gastric peptides[4,16-18]. In accordance with this, the serum G-17fast levels were higher in the non-BE patients with gastritis than in those without. However, a surprise was that gastritis did not clearly raise the G-17fast concentrations in the present BE patients. Three of the nineteen BE patients had chronic H pylori gastritis and all had low serum G-17fast levels that did not differ from those in BE patients without gastritis.

The observations suggest that the inverse relationship between G-17fast and BE is a genuine characteristic of the Barrett'S disease itself, and is not a result from gastric inflammation or atrophy, or H pylori. The low mean and median levels of G-17fast in BE patients are best explained by assuming that the basal intragastric acidity (basal acid output, BAO) tends to be higher in BE patients than in ordinary dyspeptic patients referred to diagnostic endoscopy. High intragastric acidity may, on the other hand, inhibit the release of G-17 from stomach mucosa, resulting thereby in low serum levels of fasting G-17. In other words, the BE patients may frequently have BAO levels that inhibit the release of G-17 from antral G cells. In two earlier studies, an elevated BAO has been shown to be a characteristic of patients with BE when compared to healthy controls[19,20].

Gastrins themselves have been linked to the pathogenesis of BE in some studies. Gastrins may have direct influences on growth and replication of the metaplastic Barrett epithelium[21] and may impair the esophageal motility and the function of the lower esophageal sphincter[22]. The present study indicates, however, that a low G-17fast in the circulation is a characteristic of BE, and that serum levels of G-17fast above 5 pmol/L are quite rare in BE patients.

Postprandial serum G-17 did not differ between BE and non-BE groups when investigated among subjects with healthy gastric mucosa. This may indicate that the post-stimulation level of serum G-17 does not reflect the intragastric acidity similarly as the fasting level of G-17 (G-17fast). Instead, the G-17prand may merely indicate the number of G cells in the antral mucosa, similarly as the peak acid output and maximal acid output (MAO) are measures of the number and mass of parietal cells in the oxyntic mucosa. Supporting this conclusion, atrophic antral gastritis results in a loss of antral G cells and, consequently, the serum G-17prand levels are low in these patients[23,24].

It was reported that the serum levels of total gastrin are similar in BE patients and controls even though the BAO and MAO are significantly increased[20]. Total serum gastrin was not assayed in the present study. Total immunoreactive gastrin consists of several gastrin fragments of which one-third are G-17 molecules under fasting conditions[25]. The fasting levels of G-17 tend to be very low in normal, healthy subjects in general, and these low G-17 concentrations may be easily eclipsed by other gastrin compounds.

In summary, the present investigation suggests that the serum level of G-17fast tends to be low in native BE patients who are not under PPI medication.

Footnotes

Science Editor Wang XL and Guo SY Language Editor Elsevier HK

References

- 1.Hirschowitz BI, Molina E. Relation of gastric acid and pepsin secretion to serum gastrin levels in dogs given bombesin and gastrin-17. Am J Physiol. 1983;244:G546–G551. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1983.244.5.G546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Müller J, Kirchner T, Müller-Hermelink HK. Gastric endocrine cell hyperplasia and carcinoid tumors in atrophic gastritis type A. Am J Surg Pathol. 1987;11:909–917. doi: 10.1097/00000478-198712000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Malmström J, Stadil F. Gastrin content and gastrin release. Studies on the antral content of gastrin and its release to serum during stimulation by food. Scand J Gastroenterol Suppl. 1976;37:71–76. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Petersen B, Andersen BN. Increased concentrations of the NH2-terminal fragment of gastrin-17 in acute duodenal ulcer and acute gastritis. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1983;18:635–641. doi: 10.3109/00365528309181650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stepan V, Sugano K, Yamada T, Park J, Dickinson CJ. Gastrin biosynthesis in canine G cells. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2002;282:G766–G775. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00167.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Spechler SJ. Barrett's esophagus and esophageal adenocarcinoma: pathogenesis, diagnosis, and therapy. Med Clin North Am. 2002;86:1423–145, vii. doi: 10.1016/s0025-7125(02)00082-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fitzgerald RC. Significance of acid exposure in Barrett's esophagus. Am J Gastroenterol. 2003;98:699–700. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2003.07321.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Falk GW. Barrett's esophagus. Gastroenterology. 2002;122:1569–1591. doi: 10.1053/gast.2002.33427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zaninotto G, Portale G, Parenti A, Lanza C, Costantini M, Molena D, Ruol A, Battaglia G, Costantino M, Epifani M, et al. Role of acid and bile reflux in development of specialised intestinal metaplasia in distal oesophagus. Dig Liver Dis. 2002;34:251–257. doi: 10.1016/s1590-8658(02)80144-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cameron AJ, Carpenter HA. Barrett's esophagus, high-grade dysplasia, and early adenocarcinoma: a pathological study. Am J Gastroenterol. 1997;92:586–591. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Romero Y, Cameron AJ, Schaid DJ, McDonnell SK, Burgart LJ, Hardtke CL, Murray JA, Locke GR. Barrett's esophagus: prevalence in symptomatic relatives. Am J Gastroenterol. 2002;97:1127–1132. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2002.05665.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gerson LB, Shetler K, Triadafilopoulos G. Prevalence of Barrett's esophagus in asymptomatic individuals. Gastroenterology. 2002;123:461–467. doi: 10.1053/gast.2002.34748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bersentes K, Fass R, Padda S, Johnson C, Sampliner RE. Prevalence of Barrett's esophagus in Hispanics is similar to Caucasians. Dig Dis Sci. 1998;43:1038–1041. doi: 10.1023/a:1018834902694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Spechler SJ. Columnar-lined esophagus. Definitions. Chest Surg Clin N Am. 2002;12:1–13, vii. doi: 10.1016/s1052-3359(03)00087-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Goetze JP, Paloheimo LI, Linnala A, Sipponen P, Hansen CP, Rehfeld JF. Gastrin-17 specific antibodies are too specific for gastrinoma diagnosis but stain G-cells. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2005;40:596–598. doi: 10.1080/00365520510015449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mulholland G, Ardill JE, Fillmore D, Chittajallu RS, Fullarton GM, McColl KE. Helicobacter pylori related hypergastrinaemia is the result of a selective increase in gastrin 17. Gut. 1993;34:757–761. doi: 10.1136/gut.34.6.757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Beardshall K, Moss S, Gill J, Levi S, Ghosh P, Playford RJ, Calam J. Suppression of Helicobacter pylori reduces gastrin releasing peptide stimulated gastrin release in duodenal ulcer patients. Gut. 1992;33:601–603. doi: 10.1136/gut.33.5.601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Laheij RJ, Van Rossum LG, De Boer WA, Jansen JB. Corpus gastritis in patients with endoscopic diagnosis of reflux oesophagitis and Barrett's oesophagus. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2002;16:887–891. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.2002.01245.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Collen MJ, Johnson DA. Correlation between basal acid output and daily ranitidine dose required for therapy in Barrett's esophagus. Dig Dis Sci. 1992;37:570–576. doi: 10.1007/BF01307581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mulholland MW, Reid BJ, Levine DS, Rubin CE. Elevated gastric acid secretion in patients with Barrett's metaplastic epithelium. Dig Dis Sci. 1989;34:1329–1334. doi: 10.1007/BF01538064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Haigh CR, Attwood SE, Thompson DG, Jankowski JA, Kirton CM, Pritchard DM, Varro A, Dimaline R. Gastrin induces proliferation in Barrett's metaplasia through activation of the CCK2 receptor. Gastroenterology. 2003;124:615–625. doi: 10.1053/gast.2003.50091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Straathof JW, Lamers CB, Masclee AA. Effect of gastrin-17 on lower esophageal sphincter characteristics in man. Dig Dis Sci. 1997;42:2547–2551. doi: 10.1023/a:1018872814428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sipponen P, Ranta P, Helske T, Kääriäinen I, Mäki T, Linnala A, Suovaniemi O, Alanko A, Härkönen M. Serum levels of amidated gastrin-17 and pepsinogen I in atrophic gastritis: an observational case-control study. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2002;37:785–791. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Väänänen H, Vauhkonen M, Helske T, Kääriäinen I, Rasmussen M, Tunturi-Hihnala H, Koskenpato J, Sotka M, Turunen M, Sandström R, et al. Non-endoscopic diagnosis of atrophic gastritis with a blood test. Correlation between gastric histology and serum levels of gastrin-17 and pepsinogen I: a multicentre study. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2003;15:885–891. doi: 10.1097/00042737-200308000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rehfeld JF, Christiansen LA, Malstrøm J, Schwartz T, Stadil F. The heterogeneity of gastrin, with reference to conversion of gastrin-17. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 1976;5 Suppl:185S–193S. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2265.1976.tb03826.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]