Abstract

Background:

Chondral lesions of the knee are commonly found during arthroscopic partial meniscectomy. The literature advises against arthroscopic medial meniscectomy in the presence of advanced chondral derangement because of unfavorable outcome. Recent studies have shown an association between obesity and chondropathy in patients with meniscal tears. The aim of this study was to assess whether body mass index (BMI) correlates with the severity of chondral lesions in patients with isolated medial meniscus tears (i.e. without ligamentous or lateral meniscal injury).

Materials and Methods:

837 knee arthroscopies were performed in a regional referral center of arthroscopic surgery between January 2011 and December 2012. Of these 168 (109 males, 59 females) patients with no axial knee deformity and no radiological signs of osteoarthritis who have had arthroscopic debridement for isolated torn medial meniscus were included in the study. The correlation between different demographic factors and the level of chondral damage reported at surgery was evaluated. The mean age of patient was 50 years (range 13-82 years) and an average BMI was 28.2 kg/m2 (range17.5-42.5 kg/m2).

Results:

Overall, regression analysis showed both age and BMI to be linearly correlated to chondral score (r = 0.53, P < 0.04); however, there were no advanced chondral lesions found in patients younger than 40 years of age and all severe lesions were at age 50 years or more. Therefore, further analysis was performed for age subgroups: patients were grouped as younger than 40, between the age of 40 and 50 (middle age) and older than 50 years. The BMI was linearly correlated to the severity of chondral score exclusively in the middle aged group (i.e. 40-50 years old). There was no correlation between activity level and chondral damage. Women had worse chondral lesions than men in all age groups.

Conclusion:

Higher BMI in middle aged patients with isolated medial meniscus tears and unremarkable radiographs may predict more advanced chondral lesions at arthroscopy.

Keywords: Body mass index, chondral lesion, meniscal tear, obesity

Keywords: Body mass index, tibial mensci, obesity, arthroscopy, knee

INTRODUCTION

The human meniscus functions as a shock absorber during dynamic movements of the knee, thus protecting the cartilage in the joint.1,2 Arthroscopic partial meniscectomy is the most frequent surgical procedure performed by orthopedic surgeons in the United States, with more than 50% of the procedures performed in patients 45 years of age or older.2,3 In the younger population, the tear is usually caused by trauma while atraumatic tears are typically seen from the 4th decade of life.4 Different factors might influence the occurrence of meniscal tears such as level of activity, age, gender, abnormal leg axis and obesity.5,6,7,8 Obesity is currently considered an epidemic that is associated with general health comorbidities and osteoarthritis (OA).9,10 Although favorable results for arthroscopic partial meniscectomies would be expected in young, fit and healthy patients, many partial meniscectomies are performed on overweight patients. The clinical outcome of surgical treatment is also affected by additional intraarticular pathologies, particularly chondral lesions.11 The literature advises against arthroscopic medial meniscectomy in the presence of advanced chondral derangement because of unfavorable outcome.12,13 Thus, diagnosing chondral lesions prior to surgery can affect decision making. Recent studies have shown an association between obesity and chondropathy in patients with meniscal tears; however, these studies have also included ligamental injuries and did not specify the age in which this correlation is most significant.14,15

The primary aim of this study was to assess the correlation between body mass index (BMI) and the severity of chondral lesions in patients with isolated medial meniscus tears (i.e. without ligamentous or lateral meniscal injury). A secondary objective was to evaluate the influence of other demographic factors on the surgical cartilage lesions. We hypothesized that obese patients would have significantly worse chondral lesions than patients with normal weight regardless of age, gender and level of activity.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

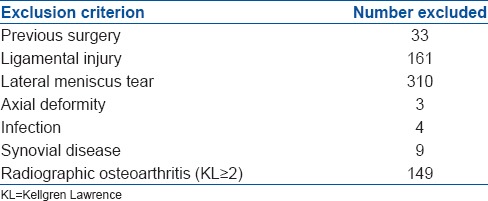

837 knee arthroscopies were performed in our institution between January 2011 and December 2012. Of these, 168 fulfilled the inclusion criteria and were included for data analysis. The study included patients with no axial knee deformity and no radiological signs of OA who have had arthroscopic debridement for torn medial meniscus pain in the knee, with or without associated mechanical symptoms not relieved by conventional methods, with clinical signs of torn medial meniscus supported by magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and weight bearing radiographs with Kellgren and Lawrence16 Grade 0 or 1 at the baseline visit. Those who have had previous knee surgery, lateral meniscus tear, injured ligament or inflammatory arthritis were excluded [Table 1]. Prior to this study a local institutional review board approval was obtained.

Table 1.

Exclusion criteria

Information was retrieved from patients’ charts and surgical reports. All preoperative evaluations and operations were undertaken by three senior orthopedic surgeons (BH, SB, RT) who were experienced in knee arthroscopy and who work together in the same unit. Radiographs were assessed by two senior physicians independently, a radiologist and an orthopedic surgeon. Surgery was done under general anesthesia with the patient in the supine position. A leg holder and tourniquet were placed around the thigh of the affected leg. Standard anterolateral and anteromedial knee portals were used. Diagnostic arthroscopy was performed to evaluate abnormal findings. Medial meniscal tears were trimmed to a stable rim. At surgery, cartilage lesions were probed, measured and then graded according to the international cartilage repair society (ICRS) classification.17 The severity of chondral damage was determined by the ICRS grade and the number of compartments involved. If two or more compartments had an ICRS score of at least 2 then the total score was raised by 1 point (i.e. the chondral score range was 0-5).

Body mass index was considered normal at 18.5-24.9 kg/m2, overweight at 25-29.9 kg/m2 and obese if ≥30 kg/m2 values, according to the US national institute of health.

Activity level was graded from 0 to 4 according to the patient occupation (sedentary, physical) and sports participation (no participation, mild recreational, intensive recreational and professional). Grade 0 activity level was given to a sedentary profession with no sports activity, Grade 1 to sedentary with mild recreational sports activity, Grade 2 if either physical profession or intensive recreational activity, Grade 3 if physical profession and intensive recreational activity and Grade 4 for professional athlete.

Statistical analysis

Results were expressed by descriptive methods (mean, range). A one-way analysis of variance was used to compare the differences in parameters (such as BMI) between age subgroups. Chondral score was modeled as a function of age, BMI and activity level with the use of multivariate regression analysis. A point-biserial correlation coefficient was used to evaluate correlation between nominal and interval parameters (such as gender and chondral score). P value was considered to be statistically significant if it was less than 0.05.

RESULTS

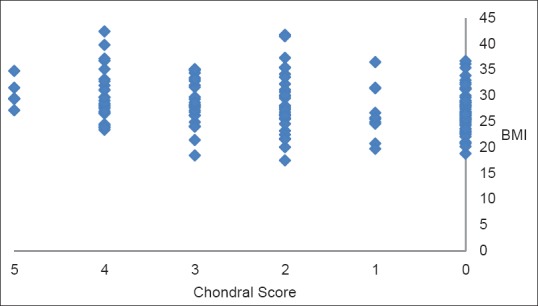

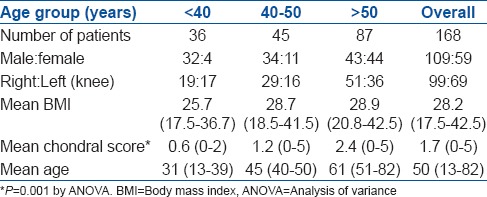

The entire patient cohort had a mean age of 50 years (range 13-82 years) and an average BMI of 28.2 (17.5-42.5) kg/m2 (overweight). Females had higher BMI [mean 29.3 (range 17.5-42.5 kg/m2) kg/m2)] than males (mean 27.5 (range 18.8-41.5 kg/m2) kg/m2). There were 68 patients with no chondral lesions, 10 with a chondral score of 1, 31 with 2, 25 with 3, 29 with 4 and 5 with 5 [Figure 1]. Overall, regression analysis showed both age and BMI to be linearly correlated to chondral score (r = 0.53, P < 0.04); however, there were no advanced chondral lesions (i.e. Grade 3 or more) found in patients younger than 40 years of age and all Grade 5 lesions were at age 50 years or more [Figure 2]. Therefore, further analysis was performed for age subgroups. Patients were grouped as younger than 40 years, between the age of 40-50 years (middle age) and older than 50 years old [Table 2]. Regression analysis for the above subgroups showed linear correlation between BMI and chondral score in the middle age (r = 0.44, P = 0.006), but not in the young or older age subgroups. Linear correlation between age to chondral score was found significant in the older age subgroup of patients (r = 0.4, P < 0.001). Activity level was graded as 0, 1, 2 and 3 in 14%, 21%, 45% and 20% of the patients, respectively with no Grade 4 (i.e. professional athletes) in this study.

Figure 1.

Correlation between body mass index and chondral score in patients with isolated medial meniscal tears

Figure 2.

Correlation between age and chondral score in patients with isolated medial meniscal tears

Table 2.

Demographic data

No correlation was found between activity level and chondral score. Female gender was found to be significantly correlated with worse chondral score in all age groups (r = 0.45, P < 0.001).

DISCUSSION

This study showed a significant linear correlation between BMI and the extent of chondropathy in middle aged patients who have had arthroscopic partial medial meniscectomy of the knee. This correlation did not exist in the younger or older age groups of patients. In addition, chondral lesions were more significant in women, but did not correlate to the level of activity. Obesity and chondropathy independently impairs the clinical outcome of partial meniscectomy. A recent study evaluated the influence of BMI on short term functional results after arthroscopy for isolated meniscal tears without chondropathy or other intraarticular pathology.18 They showed that patients with moderate or significant obesity (BMI > 26) have inferior short term outcomes to nonobese patients.

Fabricant et al.11 have examined the short term recovery after meniscectomy. Of the surgical predictor variables, only the extent of OA was predictive of recovery with worse OA negatively impacting the rate of recovery. Of the demographic and clinical variables included in their model, patient age and BMI were not associated with postoperative recovery, although older patient age and obesity have been shown before to be associated with worse long term results.19,20,21,22

Several studies highlighted the association between obesity and chondropathy in patients with meniscal tears. Ciccotti et al.14 showed a high prevalence of articular cartilage damage in patients undergoing arthroscopic surgery for meniscal pathology. Risk factors that were correlated with articular cartilage damage included increasing age, elevated BMI, medial compartment pathology and knee contractures. However, in contrast to our study, they included concomitant pathologies such as lateral meniscal and anterior cruciate ligament tears.

Laberge et al.15 compared the location and severity of morphological knee abnormalities across three BMI groups by 3T MRI. Obesity was associated with higher prevalence and severity of early degenerative changes of the cartilage and menisci in middle-aged individuals without radiographic OA. They assumed, as in prior studies, that obesity is more of a risk factor for knee lesion incidence than for progression, which underscore the need to address the obesity problem as early as possible in a patient's life.23,24 They suggested for future research to look further at younger patient populations in order to determine at what age these changes begin to occur. The population in our study showed that this relation is significant from the age of 40 years onwards. In younger age, the biochemical composition of the joint cartilage can absorb the mechanical stresses around the knee. Our findings suggest that the degenerative process accelerates from the 5th decade of life and is linearly correlated to the overload on the knee without axial deformity, represented by the BMI. On the other hand, many of the study patients over the age of 50 had significant chondropathy at surgery which was not found to be related with BMI. Therefore physicians can advise patients to reduce weight early in life and notify overweight patients about the probability of cartilage damage especially between the ages of 40 and 50 years.

Increased activity level and female gender has been implicated with generally worse results after meniscal debridement, but to the best of our knowledge previous studies on meniscal debridement did not evaluate the correlation between activity level and chondral lesions.5,20 In our study, there was no correlation found between activity level and chondral score; however, female gender was significantly correlated with worse chondral score in all age groups.

A noteworthy secondary finding from the current study is a relatively low prevalence of isolated meniscal tears in women compared to men under the age of 50 (15 of 68, 22%) and especially under the age of 40 years (4 of 32, 12.5%). Demographic sex differences were also found in previous works on meniscal tears.4,15,25,26

Malalignment or ligamentous instability of the knee increases contact pressures, elevates shear stresses and results in accelerated arthritis.27 Therefore, the current study has focused on isolated tears of the medial meniscus without ligament involvement or axial deformity in knees with unremarkable radiographs. This selection of patients was meant to reduce bias; however, incomplete information on injury pattern and duration of symptoms was not included which could have influenced the findings and decision making. Other limitations of this study are its retrospective design and the lack of outcome measures to evaluate the clinical significance of variables such as age, obesity and chondropathy.

CONCLUSION

There is a significant linear correlation between the level of BMI and the degree of chondral lesions in patients with isolated medial meniscus tears and unremarkable radiographs of the knee at the ages of 40-50 years. Therefore, surgeons can expect to find chondral lesions in middle aged obese patients prior to arthroscopic medial meniscectomy, but not necessarily in the younger or older candidates.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None.

REFERENCES

- 1.Del Pizzo W, Fox JM. Results of arthroscopic meniscectomy. Clin Sports Med. 1990;9:633–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Garrett WE, Jr, Swiontkowski MF, Weinstein JN, Callaghan J, Rosier RN, Berry DJ, et al. American Board of Orthopaedic Surgery Practice of the Orthopaedic Surgeon: Part-II, certification examination case mix. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2006;88:660–7. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.E.01208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Matsusue Y, Thomson NL. Arthroscopic partial medial meniscectomy in patients over 40 years old: A 5-to 11-year followup study. Arthroscopy. 1996;12:39–44. doi: 10.1016/s0749-8063(96)90217-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Greis PE, Bardana DD, Holmstrom MC, Burks RT. Meniscal injury: I. Basic science and evaluation. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2002;10:168–76. doi: 10.5435/00124635-200205000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jørgensen U, Sonne-Holm S, Lauridsen F, Rosenklint A. Long term followup of meniscectomy in athletes. A prospective longitudinal study. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1987;69:80–3. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.69B1.3818740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bonamo JJ, Kessler KJ, Noah J. Arthroscopic meniscectomy in patients over the age of 40. Am J Sports Med. 1992;20:422–8. doi: 10.1177/036354659202000410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Johnson RJ, Kettelkamp DB, Clark W, Leaverton P. Factors effecting late results after meniscectomy. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1974;56:719–29. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Covall DJ, Wasilewski SA. Roentgenographic changes after arthroscopic meniscectomy: Five-year followup in patients more than 45 years old. Arthroscopy. 1992;8:242–6. doi: 10.1016/0749-8063(92)90044-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Calle EE, Rodriguez C, Walker-Thurmond K, Thun MJ. Overweight, obesity, and mortality from cancer in a prospectively studied cohort of U.S. adults. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:1625–38. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa021423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Blagojevic M, Jinks C, Jeffery A, Jordan KP. Risk factors for onset of osteoarthritis of the knee in older adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2010;18:24–33. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2009.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fabricant PD, Rosenberger PH, Jokl P, Ickovics JR. Predictors of short-term recovery differ from those of long term outcome after arthroscopic partial meniscectomy. Arthroscopy. 2008;24:769–78. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2008.02.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kirkley A, Birmingham TB, Litchfield RB, Giffin JR, Willits KR, Wong CJ, et al. A randomized trial of arthroscopic surgery for osteoarthritis of the knee. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:1097–107. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0708333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Marx RG. Arthroscopic surgery for osteoarthritis of the knee? N Engl J Med. 2008;359:1169–70. doi: 10.1056/NEJMe0804450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ciccotti MC, Kraeutler MJ, Austin LS, Rangavajjula A, Zmistowski B, Cohen SB, et al. The prevalence of articular cartilage changes in the knee joint in patients undergoing arthroscopy for meniscal pathology. Arthroscopy. 2012;28:1437–44. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2012.02.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Laberge MA, Baum T, Virayavanich W, Nardo L, Nevitt MC, Lynch J, et al. Obesity increases the prevalence and severity of focal knee abnormalities diagnosed using 3T MRI in middle-aged subjects – Data from the Osteoarthritis Initiative. Skeletal Radiol. 2012;41:633–41. doi: 10.1007/s00256-011-1259-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kellgren JH, Lawrence JS. Radiological assessment of osteo-arthrosis. Ann Rheum Dis. 1957;16:494–502. doi: 10.1136/ard.16.4.494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Brittberg M, Winalski CS. Evaluation of cartilage injuries and repair. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2003;85-A(Suppl 2):58–69. doi: 10.2106/00004623-200300002-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Erdil M, Bilsel K, Sungur M, Dikmen G, Tuncer N, Polat G, et al. Does obesity negatively affect the functional results of arthroscopic partial meniscectomy? A retrospective cohort study. Arthroscopy. 2013;29:232–7. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2012.08.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chatain F, Adeleine P, Chambat P, Neyret P. Société Française d’Arthroscopie. A comparative study of medial versus lateral arthroscopic partial meniscectomy on stable knees: 10-year minimum followup. Arthroscopy. 2003;19:842–9. doi: 10.1016/s0749-8063(03)00735-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Roos EM, Ostenberg A, Roos H, Ekdahl C, Lohmander LS. Long term outcome of meniscectomy: Symptoms, function, and performance tests in patients with or without radiographic osteoarthritis compared to matched controls. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2001;9:316–24. doi: 10.1053/joca.2000.0391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Englund M, Lohmander LS. Risk factors for symptomatic knee osteoarthritis fifteen to twenty two years after meniscectomy. Arthritis Rheum. 2004;50:2811–9. doi: 10.1002/art.20489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Harrison MM, Morrell J, Hopman WM. Influence of obesity on outcome after knee arthroscopy. Arthroscopy. 2004;20:691–5. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2004.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cooper C, Snow S, McAlindon TE, Kellingray S, Stuart B, Coggon D, et al. Risk factors for the incidence and progression of radiographic knee osteoarthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2000;43:995–1000. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(200005)43:5<995::AID-ANR6>3.0.CO;2-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Niu J, Zhang YQ, Torner J, Nevitt M, Lewis CE, Aliabadi P, et al. Is obesity a risk factor for progressive radiographic knee osteoarthritis? Arthritis Rheum. 2009;61:329–35. doi: 10.1002/art.24337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Englund M, Guermazi A, Gale D, Hunter DJ, Aliabadi P, Clancy M, et al. Incidental meniscal findings on knee MRI in middle-aged and elderly persons. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:1108–15. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0800777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Salata MJ, Gibbs AE, Sekiya JK. A systematic review of clinical outcomes in patients undergoing meniscectomy. Am J Sports Med. 2010;38:1907–16. doi: 10.1177/0363546510370196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.McDermott ID, Amis AA. The consequences of meniscectomy. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2006;88:1549–56. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.88B12.18140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]