Abstract

Male hypogonadotropic hypogonadism (MHH), a disorder associated with infertility, is treated with testosterone replacement therapy (TRT) and/or gonadotropins replacement therapy (GRT) (TRT and GRT, together with HRT hormone replacement therapy). In Japan, guidelines have been set for treatment during adolescence. Due to the risk of rapid maturation of bone age, low doses of testosterone or gonadotropins have been used. However, the optimal timing and methods of therapeutic intervention have not yet been established. The objective of this study was to investigate the current situation of treatment for children with MHH in Japan and to review a primary survey involving councilors of the Japanese Society for Pediatric Endocrinology and a secondary survey obtained from 26 facilities conducting HRT. The subjects were 55 patients with MHH who reached their adult height after HRT. The breakdown of the patients is as follows: 7 patients with Kallmann syndrome, 6 patients with isolated gonadotropin deficiency, 18 patients with acquired hypopituitarism due to intracranial and pituitary tumor, 22 patients with classical idiopathic hypopituitarism due to breech delivery, and 2 patients with CHARGE syndrome. The mean age at the start of HRT was 15.7 yrs and mean height was 157.2 cm. The mean age at reaching adult height was 19.4 yrs, and the mean adult height was 171.0 cm. The starting age of HRT was later than the normal pubertal age and showed a significant negative correlation with pubertal height gain, but it showed no correlation with adult height. As for spermatogenesis, 76% of the above patients treated with hCG-rFSH combined therapy showed positive results, though ranging in levels; impaired spermatogenesis was observed in some with congenital MHH, and favorable spermatogenesis was observed in all with acquired MHH. From the above, we propose the establishment of a treatment protocol for the start low-dose testosterone or low-dose gonadotropins by dividing subjects into two groups to determine different treatment protocols, acquired and congenital MHH, and to conduct them at a timing closer to the onset of puberty, namely, at a timing near entrance to junior high school. We also propose a new HRT protocol using preemptive FSH therapy prior to GRT aimed at achieving future fertility in patients with congenital MHH.

Keywords: male hypogonadotropic hypogonadism, gonadotropins replacement therapy, MHH treatment protocol, rFSH pretreatment, pubertal induction

Introduction

Male hypogonadism is a disorder characterized by the absence of pubertal development, or discontinuation or regression of the maturation of secondary sex characteristics, and infertility. The causes of this disorder are divided into two groups; 1) primary hypogonadism due to testis failure (hypergonadotropic hypogonadism), and 2) male hypogonadotropic hypogonadism (MHH) due to insufficient secretion of gonadotropins (LH, FSH). The etiologies of MHH are generally classified into three groups: congenital MHH including isolated gonadotropin deficiency, Kallmann syndrome, CHARGE syndrome, etc., acquired MHH caused by structural lesions of the hypothalamic pituitary region; and idiopathic MHH occurring in association with hypopituitarism after breech delivery (1).

For the treatment of MHH, testosterone replacement therapy (TRT) and/or gonadotropin replacement therapy (GRT) are performed (1,2,3,4,5,6) [(TRT and GRT, together with hormone replacement therapy (HRT)]. In Japan, guidelines have been set for treatment during adolescence (2). Due to the risk of rapid maturation of bone age, low doses of testosterone (2) or gonadotropins (hCG) (3) have been used. The purposes of MHH treatment during childhood are to improve psychosocial problems associated with delayed puberty (7), to achieve normal adult height and to obtain fertility (spermatogenesis); however, the optimal timing for the initiation of these treatments as well as the treatment methods have not been established yet on a global scale. In this study, we report the results of a questionnaire survey involving councilors of the Japanese Society for Pediatric Endocrinology and describe the current situation concerning the treatment of patients with MHH in pediatrics. In addition, based on the current situation, we propose a treatment protocol for MHH during pubertal ages.

Subjects and Methods

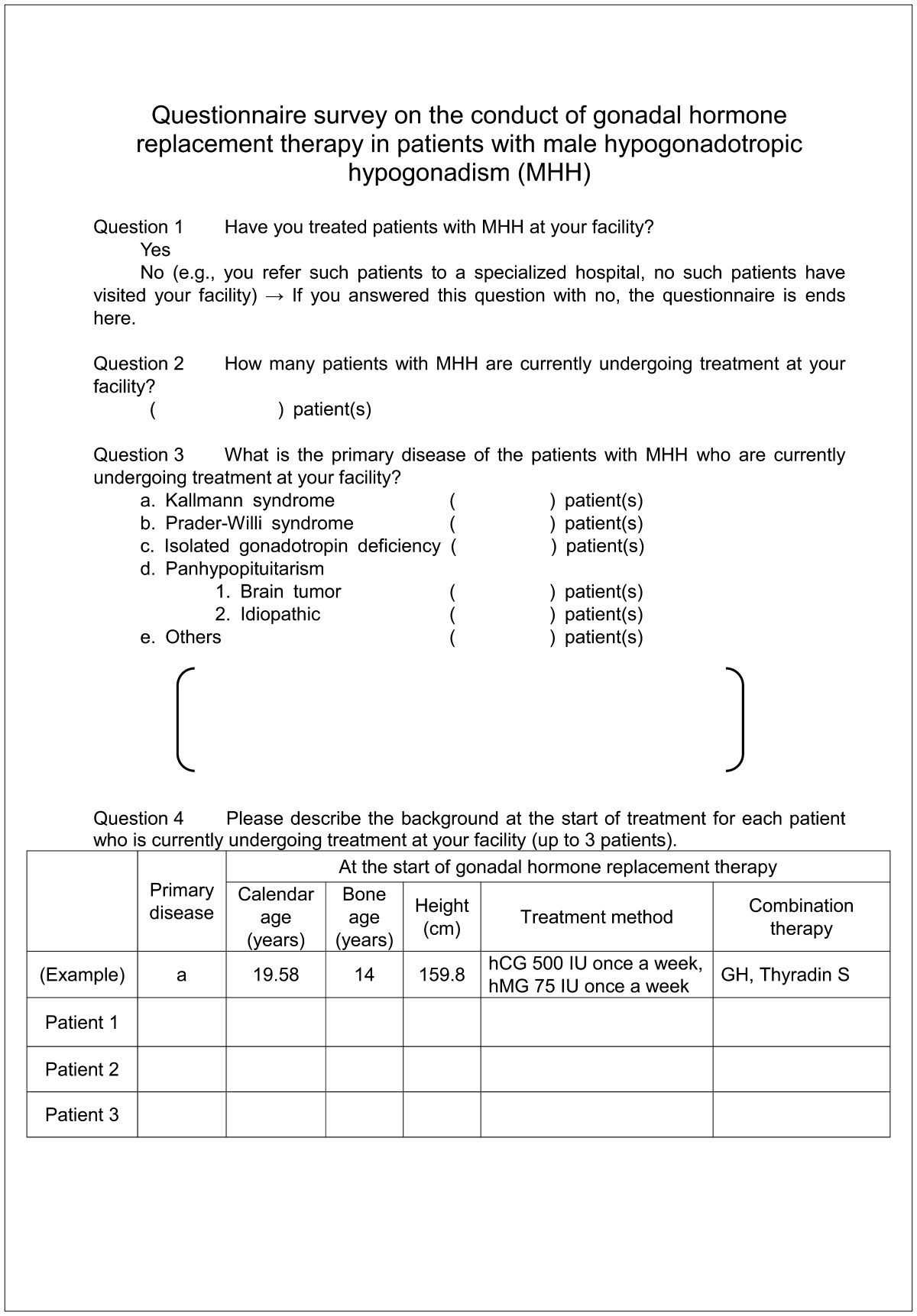

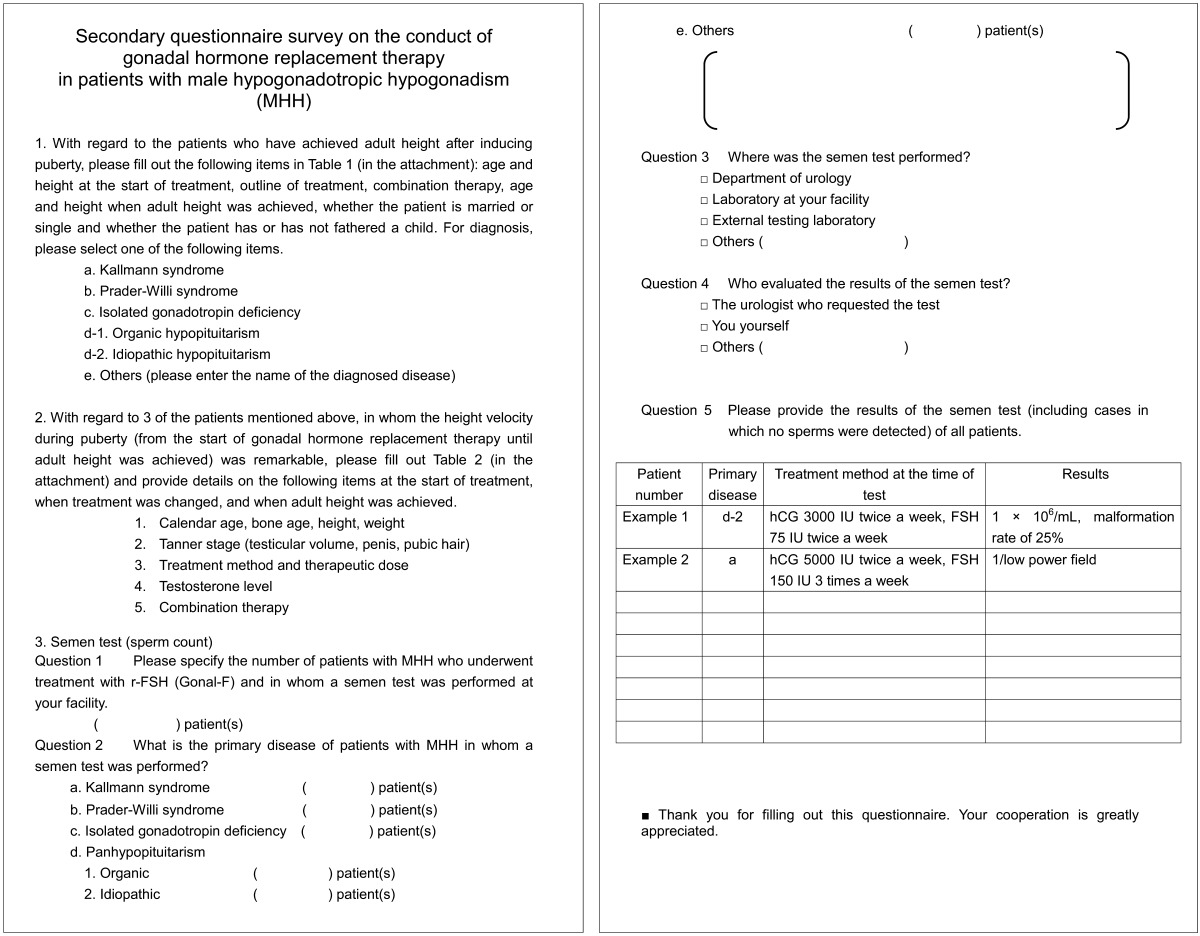

We set up a primary questionnaire survey of the treatment of patients with MHH on the underlying disease, age and height at the start of treatment and at adult height, kind of HRT, and long-term course of treatment (Table 1). We sent the primary questionnaire to 158 councilors of the Japanese Society for Pediatric Endocrinology and received responses from 43 facilities. We sent a secondary questionnaire survey (Table 2) on the details of the course of treatment and the presence or absence of a semen test to 26 facilities where GRT had been performed, and we received responses from 15 facilities.

Table 1. First questionnaire survey.

Table 2. Secondary questionnaire survey.

For the statistical analysis, we used the StatView software. Height gain during puberty is defined as the height difference from the start of treatment to when adult height is achieved. Differences in mean values among disease groups and among initial HRT groups were tested by the Bonferroni test. Differences were judged as significant when p values were less than 0.05.

Results

Results of the primary questionnaire survey

(1) Underlying disease of MHH and modalities of HRT in clinical practice

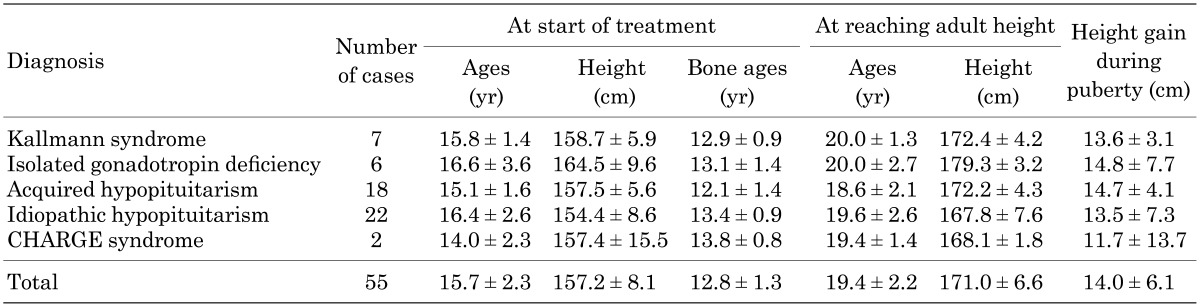

Reports on 55 patients were obtained. As shown in Table 3, and the diagnoses of these patients were Kallmann syndrome in 7 patients, isolated gonadotropin deficiency in 6 patients, acquired hypopituitarism due to intracranial and pituitary tumors in 18 patients, classical idiopathic hypopituitarism due to breech delivery in 22 patients, and CHARGE syndrome in 2 patients. Patients with Prader-Willi syndrome were not reported in this study. In all patients, the mean age at the start of HRT therapy was 15.7 yrs, mean height was 157.2 cm, mean age at adult height was 19.4 yrs, and mean adult height was 171.0 cm. There were no significant differences in age at the start of HRT and at adult height among the disease groups. There were significant differences in height at the start of HRT (p < 0.005) and adult height between patients with isolated gonadotropin deficiency and those with CHARGE syndrome (p < 0.0001); however, no significant differences in height at the start of HRT and adult height were observed among the other groups. There was no significant difference in the mean bone age at the start of HRT among the disease groups (Table 3). The mean height gain during puberty of all patients was 14.0 cm, and there were no significant differences in height gain during puberty among the disease groups (Table 3).

Table 3. Clinical characteristics at start of HRT and at reaching adult height of the groups of children with MHH.

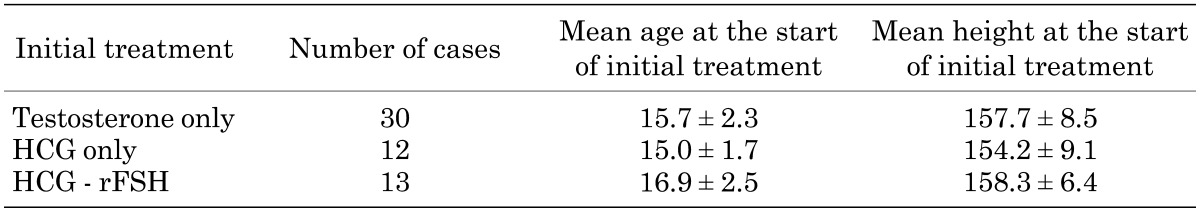

As an initial HRT, 30 patients received testosterone monotherapy, 12 patients received hCG monotherapy, and 13 patients received hCG-rFSH combination therapy (Table 4). There were significant differences in age at the start of HRT between patients who received testosterone monotherapy and patients who received hCG-rFSH combination therapy (p = 0.03). There were no significant differences in adult height among the initial HRT groups.

Table 4. Initial HRT for MHH.

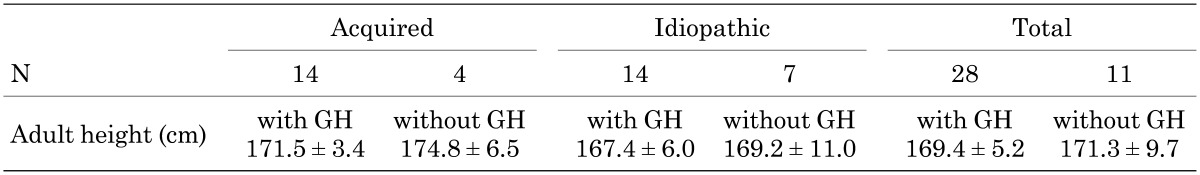

Fourteen patients with acquired MHH and 14 patients with idiopathic MHH had been receiving HRT with GH therapy. There were no significant differences in adult height between patients with and without GH treatment (Table 5).

Table 5. Adult height of MHH patients with and without GH.

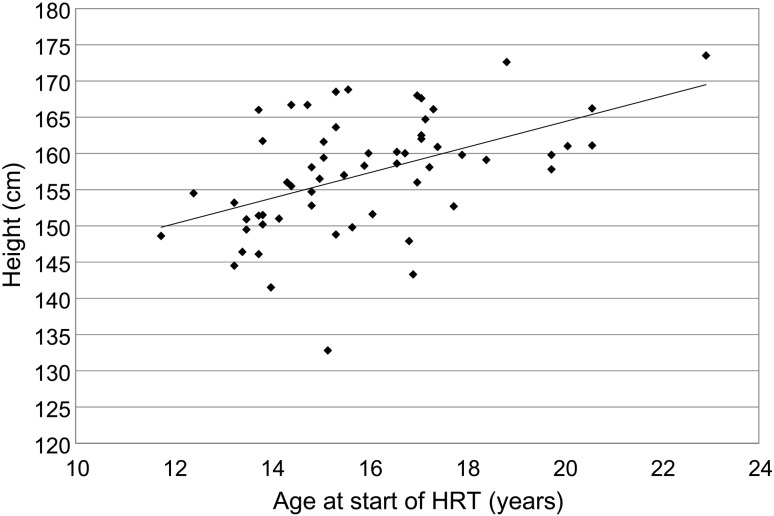

(2) Correlation between age and height at the start of HRT (Fig. 1)

Fig. 1.

Correlation between age and height at the start of HRT.

Figure 1 shows the correlation between age and height at the start of HRT in MHH. There was a significant positive correlation (r = 0.728, p < 0.0001).

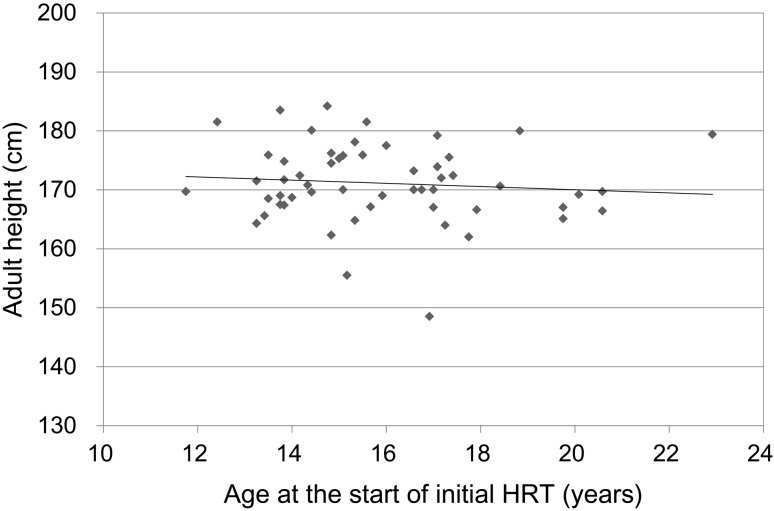

(3) Correlation between age at the start of HRT and adult height (Fig. 2)

Fig. 2.

Correlation between age at the start of HRT and adult height.

As shown in Fig. 2, no correlation was observed between age at the start of HRT and adult height. The mean adult height of 13 patients who started HRT at younger than 14 yrs old was not significantly different from that of 42 patients who started at 14 yrs old or older (171.6 cm vs. 171.0 cm). Comparing of Fig. 1 with Fig. 3, the mean increase in height before pubertal induction with HRT [1.8 cm/yr (Fig. 1)] is not greater than the mean decrease in pubertal height gain [2.1 cm/yr (Fig. 3)] anymore. Therefore, regardless of the age at the start of HRT, no significant differences were observed for adult height.

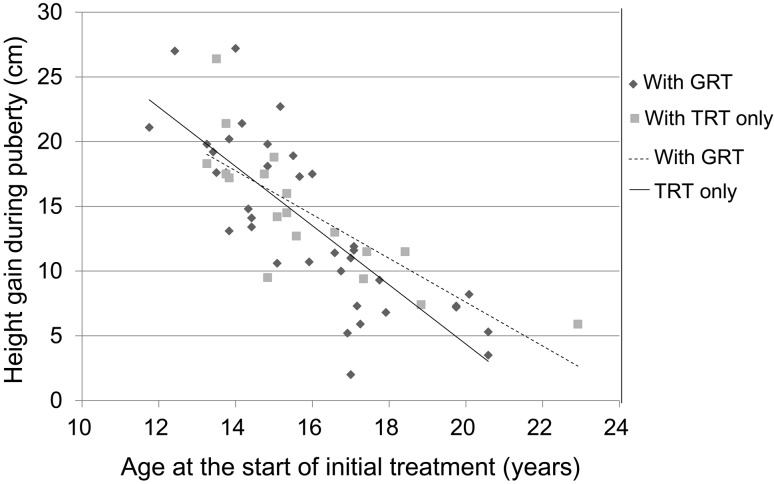

Fig. 3.

Correlation between age at the start of initial HRT and height gain during puberty.

(4) Correlation between age at the start of HRT and height gain during puberty (Fig. 3)

As shown in Fig. 3, a significant negative correlation was observed between age at the start of HRT and height gain during puberty (total, r = −0.793; TRT alone, r = −0.786; GRT, r = −0.800). The younger the patient’s age at the start of HRT was, the greater the pubertal height gain achieved. No significant difference was observed for height gain during puberty between GRT and TRT alone.

Results of the secondary questionnaire survey

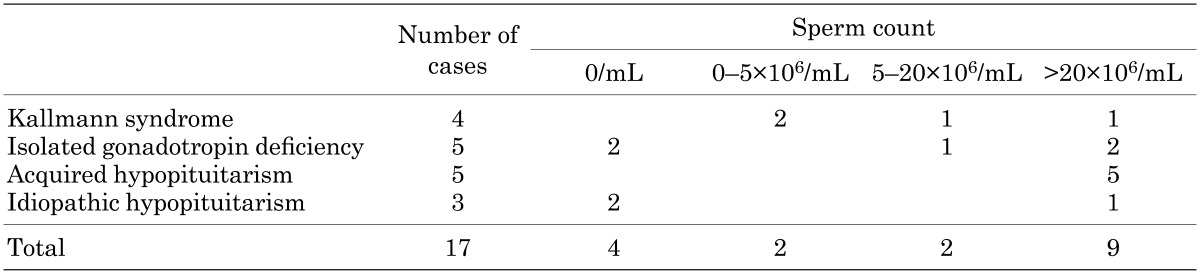

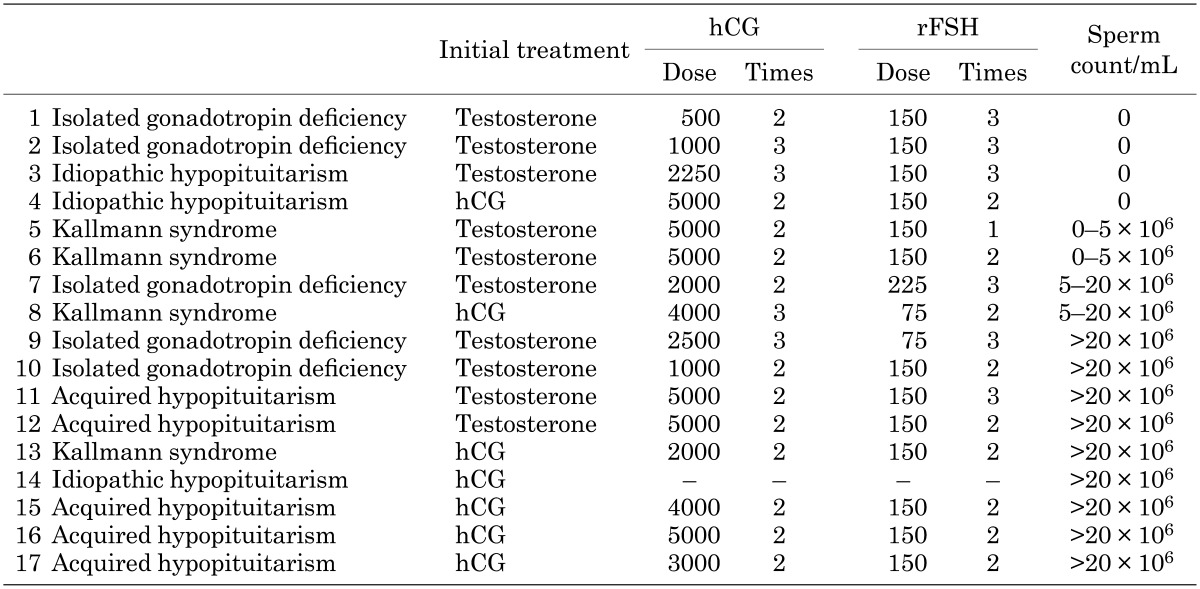

At nine facilities, 17 patients underwent a semen test after receiving hCG-rFSH combination therapy. At six facilities, the obstetrician or the gynecologist conducted and evaluated the semen test. The etiology of MHH and the semen test results are shown in Table 6. In 13 of 17 patients (76%), spermatogenesis was observed. Ten out of 17 patients received testosterone only as pretreatment and the remaining 7 patients only received hCG pretreatment. When a sperm count greater than 5 × 106/ml was defined as favorable, in patients with acquired hypopituitarism, spermatogenesis was favorable after conducting treatment with an hCG-rFSH combination therapy. In some of the patients with Kallmann syndrome, isolated gonadotropin deficiency (congenital MHH), and idiopathic hypopituitarism, poor spermatogenesis was observed (Tables 6 and 7). There were no significant differences in sperm count between testosterone only pretreatment and hCG only pretreatment (p = 0.07) (Table 7). The percentage of favorable results was greater in patients with hCG pretreatment than patients with testosterone only pretreatment.

Table 6. Sperm count after treatment.

Table 7. Pretreatment, dose and frequency for the combination therapy with hCG and rFSH and sperm count after treatment.

Discussion

Adult height

Up until now, induction of secondary sexual characteristics using HRT has started at an older age even if patients had been diagnosed as having MHH at a younger age. It had been considered that the adult height of MHH patients would remain shorter than that of normal children due to rapid maturation of secondary sex characteristics and advancement of bone age by early induction of HRT (8).

The questionnaire survey results concerning HRT in patients with MHH showed that doctors decided to start HRT at around 15 yrs old with careful consideration of an adult height (3 to 4 yrs later than the onset of puberty in healthy children) of around 155 cm on average. The patients had gained pubertal growth of approximately 15 cm, and they reached their adult heights equivalent to those of healthy individuals. The patients in early treatment groups in which HRT was initiated at the age of 12 to 13 yrs old reached similar adult heights to those in groups in which treatment was initiated later (from the age of 14 yrs old or older). Thus, the questionnaire survey revealed that the age at initiation of HRT does not in fact relate to adult height.

Moreover, the results of our analysis show that the younger the treatment is started, the greater the pubertal height gain is. The relation between the age at onset of puberty and the pubertal height gain is also observed in normal healthy children. In normal children whose heights are similar before puberty, the later pubertal onset occurs, the taller the adult heights achieved (9, 10). Since the increase in height before onset of puberty is greater than the decrease in pubertal height gain in the case of normal children, their adult height becomes greater when onset of puberty is delayed. The growth velocity gradually decreases toward onset of puberty and remains low. In the case of MHH, most of the children are already at the ages of low growth velocity, and as shown by the above results, the increase in height before starting HRT is not greater than the decrease in pubertal height gain caused by delaying pubertal induction. Therefore, regardless of the age at the start of HRT, no significant differences were observed for adult height in MHH patients. Our result poses a question regarding the validity of setting the timing of pubertal induction much later than the normal onset of puberty. Therefore, we should consider the modality and doses for HRT starting close to the age of normal pubertal onset so that second sex characteristics develop more slowly, much like pubertal development in normal children (3), while bone age is advanced to achieve normal adult height. Moreover, it has already been established in this study that there are no significant differences in adult height among initial HRT with testosterone, hCG only or hCG-rFSH combination therapy.

Additionally, regardless of GH treatment, adult height in acquired MHH patients is almost the same for HRT only and the combination therapy using HRT and GH treatment, and there are no other reports that indicate the effectiveness of the combination therapy with HRT and GH treatment.

Spermatogenesis and validity of rFSH pretreatment

In foreign reports, as in Japan, puberty is mainly induced by intramuscular injection of small doses of testosterone (25 to 75 mg/dose), which are then gradually increased up to an adult dosage (1, 2, 4, 5, 8, 11, 12) for a mean period of about 2 years during childhood. In testosterone therapy, doses can be easily adjusted for pubertal induction, and the burden on patients is small. The downside is testosterone inhibits spermatogenesis, more so like a contraceptive drug; however, after discontinuation, recovery of spermatogenesis has been confirmed (13,14,15,16,17). The effects of long-term use of this testosterone therapy on future spermatogenesis and testicular enlargement have yet to be discovered.

In our study, fertility was evaluated based on a semen test, and we found that spermatogenesis tended to be poorer in patients with congenital MHH than in those with acquired MHH even though they received treatment with the hCG-rFSH combination therapy.

We have also often experienced that in patients with Kallmann syndrome, testicular volume does not increase even with hCG-rFSH combination therapy.

During fetal development and infancy, along with GnRH-induced so-called “mini puberty”, FSH levels rise. It is known that Sertoli cells and spermatocytes proliferate under the influence of FSH, thus leading to development of the testis (18). In addition, it has been reported that in patients with congenital MHH, there is a lack in the increase of Sertoli cells both during mini puberty and puberty, and the testicular volume is less than 4 mL (19).

Dwyer et al. (19) conducted rFSH pretreatment (75–150 IU daily) for 4 months among 13 patients over 17 yrs old, in whom the possibility of delayed puberty was ruled out and the testicular volume was 4 mL or less, in order to establish physiological conditions similar to mini puberty. It was reported that as a result of this treatment, spermatogenesis and fathering children was observed in these patients (19). Their results also support that as in the case of patients with congenital MHH who may lack mini puberty, pretreatment with rFSH followed by rFSH plus hCG combination therapy in patients is effective in stimulating testicular development and spermatogenesis for future fertility.

Raivio et al. (20) reported rFSH treatment prior to pubertal induction with the combination of rFSH and hCG in boys with prepubertal onset of congenital or acquired MHH who were 9.9–17.7 yrs old. In this study, 1.5 IU/kg rFSH was used 3 times weekly (180–450 IU/wk) for 2 mo up to 2.8 yrs, and testicular volume and circulating inhibin B levels increased; successful spermatogenesis was induced by the combination of hCG and rFSH following rFSH priming. However, some patients with evidence of absent mini puberty had a significantly lower peak inhibin B value in response to rFSH than the other boys who experienced mini puberty when treated with Raivio’s method. On the other hand, rFSH pretreatment (75–150 IU/daily for four months) by Dwyer’s method increased inhibin B levels into the normal range and doubled the testicular volume in all patients with congenital MHH who did not experienced mini puberty. Therefore, rFSH pretreatment by Dwyer’s method may provide more favorable effects for spermatogenesis and development of testicular volume. Similarly, Young et al. (21) administered daily subcutaneous injections of 150 IU rFSH for 1 month to eight patients 18–31 years old with untreated congenital MHH prior to combined rFSH and hCG treatments, and the inhibin B levels of the patients increased and raised their sperm density. During rFSH monotherapy, their serum testosterone levels did not vary. Based on these results, it can be suggested that FSH monotherapy can help achieve fertility without undesired rapid progression of puberty as a results of testosterone.

Psychosocial aspects

The optimal timing of pubertal induction is very important for MHH in adolescence for a host of reasons. Adverse effects of delayed puberty such as short stature, childlike appearance, and the absence of secondary characteristics occasionally cause psychosocial problems (7, 22). Moreover, many patients face difficulty in how to cope with/control their newfound sexuality (1). Therefore, we should contemplate optimal timing of pubertal induction for patients with MHH during childhood diagnosed at an early stage, which is considered to improve psychosocial problems due to delayed puberty.

Treatment protocols for MHH during childhood

We propose new treatment protocols for patients with MHH during childhood diagnosed at an early stage, which is considered to be effective for achieving normal adult height, spermatogenesis and fertility after developing physiological secondary sex characteristics equivalent to those in healthy individuals. For acquired MHH patients, we undertake a new HRT protocol using low doses of testosterone monotherapy and/or hCG-rFSH combination therapy. For congenital MHH patients, we offer a new GRT protocol using preemptive FSH therapies.

Survivors of childhood brain tumors following treatment with chemotherapy with or without radiotherapy and testicular irradiation are associated with a high risk of primary and/or secondary hypogonadism (23). If their testicular volume is 2 mL or less, rFSH pretreatment could be one of the options for HRT.

1) Protocols using low-doses of testosterone monotherapy or hCG-rFSH combination therapy for acquired MHH patients

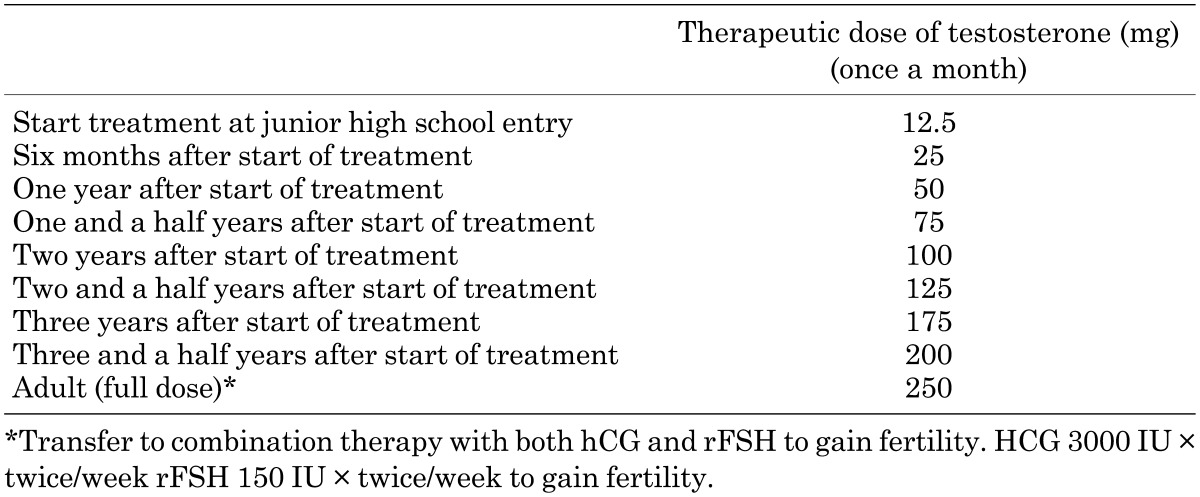

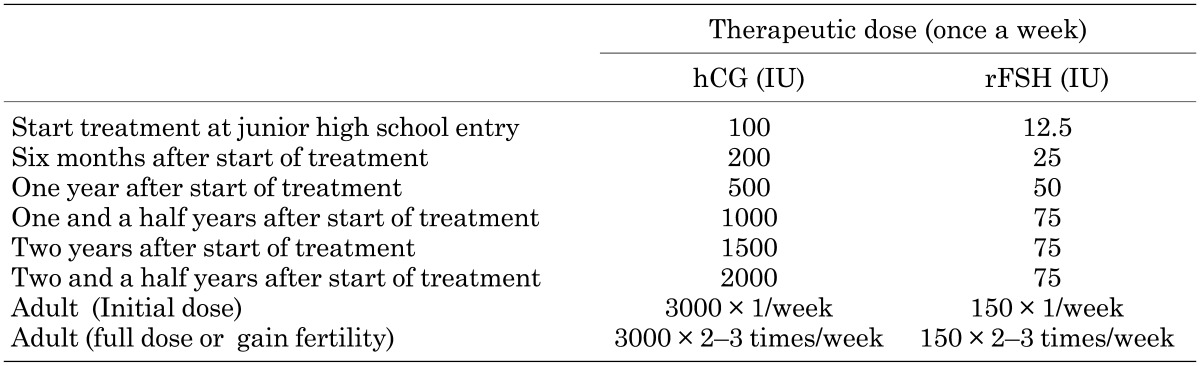

We propose low dose testosterone once a month or low-dose hCG-rFSH therapy once a week to start at entry into junior high school as shown in Tables 8-1 and 8-2 in patients with acquired MHH. Doses are increased gradually every 6 mo. The adult dose of testosterone is 250 mg every month, and hCG-rFSH is 3000 IU of hCG and 75 IU of rFSH every week. The dose of hCG is changed according to the serum testosterone level. When a patient wishes to gain fertility, 3000 IU of hCG and 150 IU of rFSH should be administered twice or thrice a week. Both of these therapies are it is expected to induce the maturation of physiological secondary sex characteristics over a period of 4 to 5 yrs.

Table 8-1. Testosterone monotherapy protocol for acquired MHH.

Table 8-2. hCG-rFSH protocol for acquired MHH.

2) Protocol using preemptive FSH therapies for congenital MHH patients

Pretreatment with rFSH monotherapy followed by rFSH and hCG combination therapy: We propose to perform rFSH pretreatment for 2 mo as described above in patients with congenital MHH who have a small testicular volume (2 mL or less) and may have poor spermatogenesis due to the genetic aetiology of MHH (i.e, Kallmann syndrome, isolated gonadotropin deficiency, etc.) (24) It was decided that the initial treatment would be sc injection of 75 IU rFSH daily for 2 mo. Dwyer et al. (19) used a 4-mo rFSH pretreatment, but the inhibin B levels after 2 mo of rFSH treatment reached the highest levels, which were similar to the normal range. Through direct personal communication with Pitteloud [CHUV, corresponding author of Dwyer et al. (19)], we confirmed that a 2-mo span of rFSH pretreatment is sufficient.

Conclusion

In HRT for patients with MHH during childhood, it is desirable to conduct TRT and/or GRT along with the physiological pubertal maturation process, to achieve normal adult height, to obtain fertility in the future, and in parallel, to reduce psychosocial problems resulting from delayed puberty. In this study, we conducted a questionnaire survey on the treatment of MHH in pediatric practice, and proposed an MHH treatment protocol for use in pediatrics. In the future, for confirmation of the usefulness/validity of this treatment protocol, we plan to accumulate treatment data of cases with MHH during childhood based on this protocol. As for all the methods discussed, the reality is that they are still at investigational levels, and therefore further research is necessary, especially at a pediatric level, to establish an MHH treatment protocol in the future.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to councilors of the Japanese Society for Pediatric Endocrinology who participated in questionnaire survey for Study Group of Treatment for MHH Japan.

References

- 1.Han TS, Bouloux PM. What is the optimal therapy for young males with hypogonadotropic hypogonadism? Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 2010;72: 731–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2265.2009.03746.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Manual for the diagnosis and treatment of decreased gonadotropin secretion. Investigational research team for functional hypothalamic and pituitary disorders, research on measures for intractable diseases. Health and labor sciences research grant (http://rhhd.info/) (Only in Japanese).

- 3.Oyama K, Nakagome Y, Kobayashi H, Satoh K, Uchida N, Sano T, et al. Examination of methods for inducing secondary sex characteristics for the treatment of male hypogonadotropic hypogonadism. Jap J Pediatr Soc 2008;112: 1667–73(Only in Japanese). [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rogol AD. New facets of androgen replacement therapy during childhood and adolescence. Expert Opin Pharmacother 2005;6: 1319–36. doi: 10.1517/14656566.6.8.1319 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nabhan Z, Eugster EA. Hormone replacement therapy in children with hypogonadotropic hypogonadism: where do we stand? Endocr Pract 2013;19: 968–71. doi: 10.4158/EP13101.OR [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Drobac S, Rubin K, Rogol AD, Rosenfield RL. A workshop on pubertal hormone replacement options in the United States. J Pediatr Endocrinol Metab 2006;19: 55–64. doi: 10.1515/JPEM.2006.19.1.55 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shiraishi K, Oka S, Matsuyama H. Assessment of quality of life during gonadotrophin treatment for male hypogonadotrophic hypogonadism. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 2014;81: 259–65. doi: 10.1111/cen.12435 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bergadá I, Bergadá C. Long term treatment with low dose testosterone in constitutional delay of growth and puberty: effect on bone age maturation and pubertal progression. J Pediatr Endocrinol Metab 1995;8: 117–22. doi: 10.1515/JPEM.1995.8.2.117 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tanaka T, Suwa S, Yokoya S, Hibi I. Analysis of linear growth during puberty. Acta Paediatr Scand Suppl 1988;347: 25–9[Suppl]. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tanaka T. Pubertal growth and maturation in healthy girls. J Jpn Ass Hum Auxo 2006;12: 3–9(Only in Japanese). [Google Scholar]

- 11.MacGillivray MH. Induction of puberty in hypogonadal children. J Pediatr Endocrinol Metab 2004;17(Suppl 4): 1277–87. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Isolated Gonadotropin-Releasing Hormone (GnRH) Deficiency Buck C, Balasubramanian R, Crowley WF. In: Pagon RA, Adam MP, Bird TD, Dolan CR, Fong CT, Stephens K, editors. GeneReviews™ [Internet]. Seattle (WA): University of Washington, Seattle; 1993-2013. 2007. May 23 [updated 2013 Jul 18]. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Anderson RA, Kelly RW, Wu FC. Comparison between testosterone enanthate-induced azoospermia and oligozoospermia in a male contraceptive study. V. Localization of higher 5 alpha-reductase activity to the reproductive tract in oligozoospermic men administered supraphysiological doses of testosterone. J Androl 1997;18: 366–71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wallace EM, Gow SM, Wu FC. Comparison between testosterone enanthate-induced azoospermia and oligozoospermia in a male contraceptive study. I: Plasma luteinizing hormone, follicle stimulating hormone, testosterone, estradiol, and inhibin concentrations. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 1993;77: 290–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kim ED, Crosnoe L, Bar-Chama N, Khera M, Lipshultz LI. The treatment of hypogonadism in men of reproductive age. Fertil Steril 2013;99: 718–24. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2012.10.052 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Moss JL, Crosnoe LE, Kim ED. Effect of rejuvenation hormones on spermatogenesis. Fertil Steril 2013;99: 1814–20. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2013.04.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bassil N, Alkaade S, Morley JE. The benefits and risks of testosterone replacement therapy: a review. Ther Clin Risk Manag 2009;5: 427–48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zacharin M, Sabin MA, Nair VV, Dabadghao P. Addition of recombinant follicle-stimulating hormone to human chorionic gonadotropin treatment in adolescents and young adults with hypogonadotropic hypogonadism promotes normal testicular growth and may promote early spermatogenesis. Fertil Steril 2012;98: 836–42. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2012.06.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dwyer AA, Sykiotis GP, Hayes FJ, Boepple PA, Lee H, Loughlin KR, et al. Trial of recombinant follicle-stimulating hormone pretreatment for GnRH-induced fertility in patients with congenital hypogonadotropic hypogonadism. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2013;98: E1790–5. doi: 10.1210/jc.2013-2518 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Raivio T, Wikström AM, Dunkel L. Treatment of gonadotropin-deficient boys with recombinant human FSH: long-term observation and outcome. Eur J Endocrinol 2007;156: 105–11. doi: 10.1530/eje.1.02315 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Young J, Chanson P, Salenave S, Noël M, Brailly S, O’Flaherty M, et al. Testicular anti-mullerian hormone secretion is stimulated by recombinant human FSH in patients with congenital hypogonadotropic hypogonadism. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2005;90: 724–8. doi: 10.1210/jc.2004-0542 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Aydogan U, Aydogdu A, Akbulut H, Sonmez A, Yuksel S, Basaran Y, et al. Increased frequency of anxiety, depression, quality of life and sexual life in young hypogonadotropic hypogonadal males and impacts of testosterone replacement therapy on these conditions. Endocr J 2012;59: 1099–105. doi: 10.1507/endocrj.EJ12-0134 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Romerius P, Ståhl O, Moëll C, Relander T, Cavallin-Ståhl E, Wiebe T, et al. Hypogonadism risk in men treated for childhood cancer. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2009;94: 4180–6. doi: 10.1210/jc.2009-0337 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Delemarre-van de Waal HA. Application of gonadotropin releasing hormone in hypogonadotropic hypogonadism—diagnostic and therapeutic aspects. Eur J Endocrinol 2004;151(Suppl 3): U89–94. doi: 10.1530/eje.0.151U089 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]