Abstract

Purpose: Sexual and gender minorities (SGM) smoke cigarettes at higher rates than the general population. Historically, research in SGM health issues was conducted in urban populations and recent population-based studies seldom have sufficient SGM participants to distinguish urban from rural. Given that rural populations also tend to have a smoking disparity, and that many SGM live in rural areas, it is vitally important to understand the intersection of rural residence, SGM identity, and smoking. This study analyzes the patterns of smoking in urban and rural SGM in a large sample.

Methods: We conducted an analysis of 4280 adult participants in the Out, Proud, and Healthy project with complete data on SGM status, smoking status, and zip code. Surveys were conducted at six Missouri pride festivals and online in 2012. Analysis involved descriptive and bivariate methods, and multivariable logistic regression. We used GIS mapping to demonstrate the dispersion of rural SGM participants.

Results: SGM had higher smoking proportion than the non-SGM recruited from these settings. In the multivariable model, SGM identity conferred 1.35 times the odds of being a current smoker when controlled for covariates. Rural residence was not independently significant, demonstrating the persistence of the smoking disparity in rural SGM. Mapping revealed widespread distribution of SGM in rural areas.

Conclusions: The SGM smoking disparity persists among rural SGM. These communities would benefit from continued research into interventions targeting both SGM and rural tobacco control measures. Recruitment at pride festivals may provide a venue for reaching rural SGM for intervention.

Key words: : drug abuse, health disparities, sexual minorities, social determinants of health

Introduction

A growing body of research identifies health disparities that negatively impact sexual and gender minorities (SGM), constituting those who identify themselves as lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer, questioning, intersex, or combinations or variations of these labels.1–3 It is well established that tobacco use is up to two times more common in SGM versus non-SGM.4–6 Evidence supports the role of minority stress, social norms, social isolation, and targeting of SGM people by tobacco companies as contributing factors to this disparity.7

The majority of studies concerning health and health behaviors among SGM populations target urban areas; little is known about smoking and tobacco use in rural SGM. One research team examining smoking in rural communities found a higher proportion of SGM smoking compared to state's general prevalence,8 but was unable to differentiate whether rural SGM actually had higher tobacco use than rural non-SGM (heterosexual and gender normative) persons in their communities. The difference between SGM and non-SGM within the rural setting is important because of evidence that rural Americans have a higher likelihood of smoking than urban dwellers.

The Out, Proud, and Healthy (OPAH) project collected data from Missouri pride festivals and online SGM populations, including SGM status, smoking information, and zip code from which rurality can be derived. As such, this data set was an excellent resource within which the current analysis begins to examine gaps in the literature.

In the state of Missouri, more of the population lives in rural areas (26%)9 than the United States as a whole (19.3%),10 and the increased proportions of smoking in rural areas hold for the state as well.11,12 The primary aims of the current analysis were to (1) describe smoking behaviors in a sample with a relatively high expected smoking prevalence, and (2) compare these factors between SGM and non-SGM as well as between rural and urban SGM participants. We also sought to determine predictors of current smoking in the overall sample. Secondary aims were (1) to quantify the geographic distribution of rural SGM to determine the breadth of rural representation for pride festival attendees and (2) explore patterns related to smoking cessation. The primary hypotheses for the current analysis were as follows: (1) SGM would have a higher proportion of smoking than both the general Missouri population and the non-SGM sample, and (2) rural Missouri SGM would have a higher proportion of smoking than urban SGM.

Methods

The University of Missouri and University of Kentucky provided respective institutional review board's approval for the study.

Design and procedures

The current cross-sectional analysis of associations and predictors of smoking relative to SGM and residence derives from the 2012 Health Behaviors, Attitudes and Habits survey (N=5243) of the OPAH project.13 OPAH used purposive sampling to collect data on tobacco use, perceptions of policies surrounding smoking, and mental health status. English-language, self-administered surveys were collected from attendees at Missouri pride festivals (Columbia, Joplin, Kansas City, Springfield, St. Louis, and Black Pride St. Louis) and through a link to an Internet survey via e-mails or listserves of Missouri SGM organizations. These pride festivals reported attendance ranging from a few hundred to approximately 125,000, of which an unknown but likely large percentage were SGM individuals. At each pride festival, a booth was rented to serve as a base from which attendees were approached and invited to anonymously complete the survey. Research staff received training in study protocols, incorporating exclusion of repeated participation from those who attended multiple pride festivals; however, attendees had to voluntarily self-disclose that they had filled out another survey.

Measures

The survey instrument consisted of 28 items and took approximately 10 minutes to complete. Basic demographics included age, race, ethnicity, and education. Three pertinent variables for the current study's analysis were created from collected data and categorized smoking status, rural/urban residence, and SGM status. Details on these variables and those for smoking and SGM status appear in Table 1. The two questions used to determine smoking status are identical to the ones used for over a decade in national surveys.14–16 Residence was assessed through self-reported residential zip code and categorized into rural versus urban residence through use of rural–urban commuting area codes (RUCAs). RUCA designation assesses urbanicity based on both city size and average commute time to an urban center. RUCA scores are based on census tracts; however, we applied a standardized dataset from the Rural Health Research Center17 to approximate RUCA from zip codes. RUCA designations fall on a scale from 1 to 9, with 1 representing a major metropolitan area and 9 the most rural or frontier area census tracts. We categorized codes 1–3 as urban and 4–9 as rural for purposes of this study, the standard dichotomization suggested by the U.S. Department of Agriculture.17,18

Table 1.

Sample Variables

| Variable | Categories | Description/rational |

|---|---|---|

| Demographics | ||

| Race | Black | Collected as 5 categories: Black/African American, Asian, white, American Indian or Alaska Native, Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander Coded “Other” category included multiracial responses. |

| White | ||

| Other | ||

| Ethnicity | Hispanic | |

| Non-Hispanic | ||

| Education | High school or less | Collected as 7 categories: less than high school, high school/GED, technical school without degree, some college without degree, 2-year college degree, 4-year college degree, postgraduate work or degree “Some college” category included categories 3–5 above. |

| Some college | ||

| 4-year degree or more | ||

| Age | 18–24 years | Reported as a continuous variable but because of nonnormal distribution was also recoded in categories based on standard census definitions. |

| 25–34 years | ||

| 35–44 years | ||

| 45–54 years | ||

| 55 years and older | ||

| Pertinent study and related variables | ||

| Smoking status | Current | Current=indicated smoking at least 100 lifetime cigarettes and smokes every or some days |

| Former | Former=indicated smoking at least 100 lifetime cigarettes and currently smokes “not at all” | |

| Never | Never=smoked <100 in lifetime | |

| Intention to quit | Trying to quit | Only asked of current smokers |

| Plan to quit within 1 month | ||

| Plan to quit within 6 months | ||

| Not planning to quit | ||

| SGM | SGM Non-SGM |

SGM=identified as any transgender/transsexual status or intersex gender or any sexual identity other than straight/heterosexual |

| Non-SGM=those not SGM | ||

| Composite SGM derived from 3 questions: | ||

| 1. Gender: man, woman, or intersex | ||

| 2. Sexual identity 1: gay, lesbian, bisexual, heterosexual/straight, don't know/not sure, or other | ||

| 3. Sexual identity 2: transgender, transsexual, or neither | ||

| Transgender and transsexual responses were combined for all analyses. If someone self-identified as “man” and chose either/or both gay and lesbian, the sexual orientation was recoded as “gay.” Likewise, a “woman” who had marked either or both was recoded as “lesbian.” If multiple genders or sexual orientations were marked, they were coded as “other” except in the gay/lesbian situation noted above. | ||

GED, General Educational Development; SGM, sexual and gender minorities.

Data analysis

Our analysis plan consisted of five steps and utilized SPSS, SAS, and ArcGIS. In order to meet study aims, SPSS 20.0 (IBM 2007) was used to perform descriptive statistics for the sample subsets with categorical variables reported in counts and frequencies and continuous data reported in means and standard deviations. (SPSS was utilized for the remainder of the analyses described unless otherwise stated.) We used chi-squared tests to compare groups on categorical variables with Fisher's exact tests used for those with 2×2 comparisons. We employed the Mann–Whitney U-test to compare mean ages because of the nonnormal distribution and performed logistic regression to test whether significant independent variables discovered in the bivariate analyses could predict smoking status. Bivariate analyses on smoking informed a logistic regression used to examine predictors of current smoking. Because this survey served as an exploratory study of attitudes and behaviors, it did not involve a priori power calculations. The goal was to obtain as many participants as possible within logistical and financial limitations. We conducted a post-hoc power analysis using the chi-squared statistics for the 2×2 comparison of both smoking in SGM versus non-SGM, as well as smoking in urban versus rural SGM. Given an alpha of 0.05 and calculated effect size from our results and sample size, the power to detect the differences was ≥0.9 in each case.

ArcGIS v10.1 (Environmental System Research, Inc.) was used to geocode each survey respondent's reported residence at the zip code level. Because zip codes do not correspond exactly to county borders, we mapped locations and calculated distances using the centroid methodology that assigns the residence at the geographic center of the zip code within a particular county.19 The centroid approach is a commonly accepted methodology19,20 to locate participants in a particular county, in this case allowing comparisons to other studies employing county-based classifications.12 For all county-level analysis, Missouri counties were categorized as urban or rural based on rural–urban continuum codes that classify counties based on adjacency to a metropolitan statistical area.21 For Missouri residents, we also estimated the straight-line distance between their location and the site of the festival where they completed the survey. Although straight-line distance approximations are known to underestimate actual travel, they never overestimate distance traveled and are commonly used in geographic studies.20

SAS 9.3 was used to perform the Mantel–Haenszel analysis comparing the proportion of former smokers among multiple subgroups.

Results

Data were collected for a total of 5243 participants. Those excluded from the present analyses included participants (1) under age 18, to better reflect populations in other datasets and facilitate comparisons, and (2) missing data on smoking status, SGM, or geocodable residential zip codes (including those corresponding to Army Post Office and Fleet Post Office locations.) To verify that excluding the 352 subjects with missing data did not affect the results, we performed sensitivity analyses for excluded versus included subjects (data not shown), and none of the results were significantly different. A total of 4280 subjects (82%) were included in the current analysis (Table 2).

Table 2.

Descriptive Statistics: 4280 Subjects 18 Years and Older Having Complete Data for SGM Status, Smoking Status, and Urban/Rural Residence (81.6% of Total Sample)

| Characteristics | N (%) or mean±SD |

|---|---|

| Age | 32.6±12.7 (range 18–80; median 28) |

| Age by census category | |

| 18–24 | 1533 (35.8%) |

| 25–34 | 1208 (28.2%) |

| 35–44 | 693 (16.2%) |

| 45–54 | 530 (12.4%) |

| ≥55 | 316 (7.4%) |

| Gender | |

| Man | 1782 (41.9%) |

| Woman | 2447 (57.5%) |

| Intersex | 23 (0.5%) |

| Transgender or transsexual | 126 (3.0%) |

| Sexual identity | |

| Gay | 1297 (30.3%) |

| Lesbian | 1087 (25.4%) |

| Bisexual | 542 (12.7%) |

| Straight/heterosexual | 1160 (27.1%) |

| Don't know/not sure | 46 (1.1%) |

| Other | 142 (3.3%) |

| SGM statusa | 3135 (73.2%) |

| Race | |

| Black | 544 (12.9%) |

| White | 3373 (80.2%) |

| Other | 287 (6.8%) |

| Hispanic ethnicity | 239 (5.6%) |

| Missouri residence | 3424 (80.0%) |

| Education level | |

| High school or less | 885 (20.7%) |

| Some college | 1733 (40.5%) |

| 4-year degree or more | 1656 (38.7%) |

| Rural residence (RUCA >3) | 428 (10%) |

| Smoking status | |

| Current | 1606 (37.5%) |

| Former | 667 (15.6%) |

| Never | 2007 (46.9%) |

| Intention to quit among current smokers | |

| Trying to quit | 430 (26.1%) |

| Plan to quit within 1 month | 239 (14.5%) |

| Plan to quit within 6 months | 612 (37.1%) |

| Not planning to quit | 367 (22.3%) |

Sexual or gender minority (SGM) is defined as anyone answering anything other than heterosexual/straight for sexual identity, or intersex for gender, or transgender or transsexual identity.

RUCA, rural–urban commuting area codes.

Descriptive

The 4280 participants ranged in age from 18 to 80, with a mean age of 31. Nearly 40% of respondents were in their 20s and 92% were under 55 years old. Nearly 75% of participants identified in an SGM category and 10% of participants reported a rural zip code. The majority of participants took the survey on paper in proportion to the general attendance at the pride festivals (St. Louis 54.3%, Kansas City 23.5%, Columbia 11.8%, Springfield 6.8%). The Joplin and St. Louis black pride festivals together contributed 2.4% of participants. Only 51 of the participants (1.2%) took the survey on the Internet. Because Internet respondents may be substantially different from those actually attending a community pride event, we undertook a sensitivity analysis excluding those participants. For the remaining 4229, there were no changes in the significant or nonsignificant associations of major variables (e.g., current smoking SGM versus non-SGM, current smoking urban versus rural SGM), or in the logistic regression.

Primary aims

SGM participants were more likely than non-SGM to be current smokers (Table 3). Because research supports differences in tobacco use among SGM subgroups,22–24 we also compared current and former smoking by sexual orientation categories and transgender identity. When comparing sexual orientations with the 126 transgender participants excluded, the proportion of current smoking for those identifying as gay (37.2%), lesbian (40.8%), bisexual (45.%), not sure (37.0%), and other (39.4%) was each significantly higher than that of heterosexuals (22.3%); at p-values ≤0.002 in all direct pairwise comparisons. Transgender subjects (n=126, inclusive of all sexual orientations) had the highest current smoking proportion of any subgroup at 51.6% (data not shown).

Table 3.

Differences in Sample Characteristics by SGM Status (N=4280)

| Characteristic | SGM, N=3135 (73.2%), N (%) or mean±SD | Non-SGM, N=1145 (26.8%), N (%) or mean±SD | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 32.5±12.4 | 32.9±13.5 | 0.929 |

| Gendera | <0.001 | ||

| Man | 1410 (45.7%) | 372 (32.5%) | |

| Woman | 1674 (54.3%) | 773 (67.5%) | |

| Race | 0.044 | ||

| Black | 419 (13.6%) | 125 (11.0%) | b |

| White | 2436 (72.2%) | 937 (82.7%) | b |

| Other | 216 (7.0%) | 71 (6.3%) | c |

| Hispanic ethnicity | 193 (6.2%) | 46 (4.0%) | 0.004 |

| Missouri resident | 2475 (78.9%) | 949 (82.9%) | 0.002 |

| Education leveld | <0.001 | ||

| High school or less | 284 (14.1%) | 92 (12.6%) | c |

| Some college | 754 (37.5%) | 215 (29.4%) | b |

| 4-year degree or more | 973 (48.4%) | 425 (58.1%) | b |

| Rural residence | 353 (11.3%) | 75 (6.6%) | <0.001 |

| Smoking status | <0.001 | ||

| Current | 1252 (39.9%) | 354 (30.9%) | b |

| Former | 495 (15.8%) | 172 (15.0%) | c |

| Never | 1388 (44.3%) | 619 (54.1%) | b |

| Intention to quit among current smokers | 0.945 | ||

| Trying to quit | 334 (26.0%) | 96 (26.4%) | |

| Plan to quit within 1 month | 183 (14.3%) | 56 (15.4%) | |

| Plan to quit within 6 months | 480 (37.4%) | 132 (36.3%) | |

| Not planning to quit | 287 (22.4%) | 80 (22.0%) | |

Intersex, n=24, not included as gender subcategory for this comparison because by definition SGM.

Significant difference contributing to the p-value.

Not contributing to the significant p-value.

Subset n=2743 of participants aged 25 and older.

When considering only SGM participants (Table 4; n=3135), rural SGM were more likely to be white, female, and less educated. Rural SGM included a strikingly high proportion of current smokers (45.9%); however, the difference between rural and urban SGM smoking did not reach statistical significance.

Table 4.

Comparison of Urban and Rural SGM (n=3135)

| Characteristic | Urban SGM, n=2782 (88.7%), N (%) or mean±SD | Rural SGM, n=353 (11.3%), N (%) or mean±SD | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 32.7±12.6 | 30.6±10.5 | 0.026 |

| Gender | 0.014 | ||

| Man | 1276 (46.3%) | 134 (38.1%) | a |

| Woman | 1459 (53.0%) | 215 (61.1%) | a |

| Intersex | 20 (0.7%) | 3 (0.9%) | b |

| Race | <0.001 | ||

| Black | 408 (15.0%) | 11 (3.2%) | a |

| White | 2117 (77.8%) | 319 (91.4%) | a |

| Other | 197 (7.2%) | 19 (5.4%) | b |

| Hispanic ethnicity | 175 (6.3%) | 18 (5.1%) | 0.413 |

| Missouri residence | 2265 (81.4%) | 201 (59.5%) | <0.001 |

| Transgender or transsexual | 119 (4.3%) | 7 (2.0%) | 0.042 |

| Education levelc | <0.001 | ||

| ≤High school | 223 (13.0%) | 51 (23.9%) | a |

| Some college | 669 (37.2%) | 85 (39.9%) | b |

| ≥4-year degree | 896 (49.8%) | 77 (36.2%) | a |

| Smoking status | 0.052 | ||

| Current | 1090 (39.2%) | 162 (45.9%) | |

| Former | 444 (16%) | 51 (14.4%) | |

| Never | 1248 (44.9%) | 140 (39.7%) | |

| Intention to quit among current smokers | 0.349 | ||

| Trying to quit | 297 (26.5%) | 37 (22.4%) | |

| Plan to quit within 1 month | 161 (14.4%) | 22 (13.3%) | |

| Plan to quit within 6 months | 408 (36.5%) | 72 (43.6%) | |

| Not planning to quit | 253 (22.6%) | 34 (20.6%) | |

Significant difference contributing to the p-value.

Not contributing to the significant p-value.

Subset n=2014 of SGM participants aged 25 and older.

To determine factors associated with smoking status in the whole sample and determine appropriate variables for the regression mode, we performed bivariate analyses based on known geographic and demographic associations with smoking. Rural residents (42.8%) were slightly more likely than urban (36.9%) to be current smokers (p=0.048). Blacks (33.5%) were less likely than whites (37.8%) and others (40.4%) to be current smokers (p<0.001). Current smoking decreased with increasing education (high school or less 54.4%, some college 43.6%, 4-year degree or more 22.0%; p<0.001). Proportion of current smokers also decreased in each successive increase in age group, from 43% in the 18–24 group to 13.3% among those over 55.

For the logistic regression, assumptions for independence, linear relationships between age and the logit transformation of the dependent variable, multicollinearity, and lack of outliers were met with the exception of the linear relationship of age to the logit transformation; therefore, age was converted to categorical data based on census age categories. Odds of current smoking were higher in those with SGM identity, lower educational level, white and other race, and age groups between 18 and 55 compared to age 55 and older (Table 5). Rural residence was not independently predictive of being a current smoker. The interaction of SGM status and nonurban residence was also not significant in the model.

Table 5.

Logistic Regression with Odds Ratios for Predicting Being a Current Smoker (N=4280)

| Factor | Odds ratio | 95% confidence interval | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| SGM | 1.35 | 1.15–1.58 | <0.001 |

| Race | <0.001 | ||

| Black | Referent | ||

| White | 1.56 | 1.27–1.91 | <0.001 |

| Other | 1.60 | 1.17–2.18 | 0.002 |

| Education | <0.001 | ||

| <High school | 4.16 | 3.43–5.04 | <0.001 |

| Some college | 2.67 | 2.27–3.13 | <0.001 |

| ≥4-year degree | Referent | ||

| Age | <0.001 | ||

| 18–24 | 2.73 | 1.91–3.90 | <0.001 |

| 25–34 | 3.80 | 2.67–5.41 | <0.001 |

| 35–44 | 2.62 | 1.80–3.78 | <0.001 |

| 45–54 | 2.21 | 1.50–3.24 | <0.001 |

| ≥55 | Referent | ||

| Rural residence | 0.73 | 0.43–2.53 | 0.267 |

| Missouri residence | 0.99 | 0.84–1.16 | 0.865 |

| SGM*rural | 1.40 | 0.77–2.53 | 0.266 |

Secondary aim

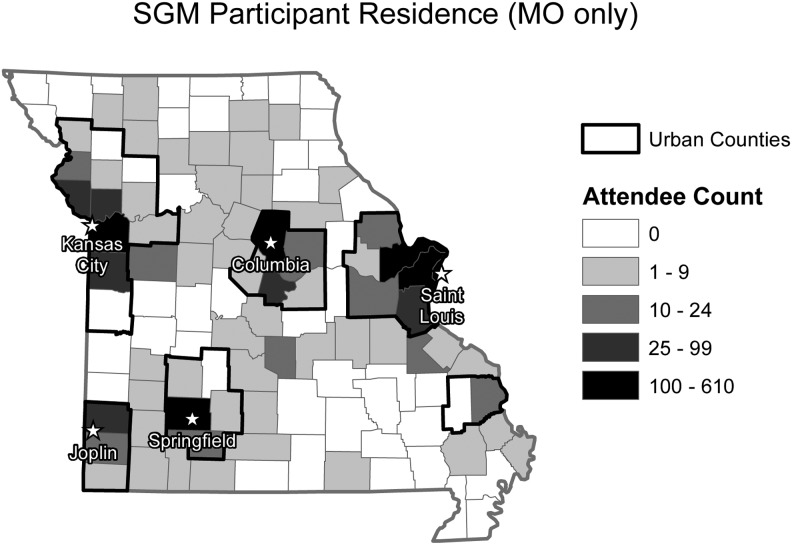

Participants reported residential zip codes from 39 different states. The median distance from the residential zip codes reported by Missouri SGM residents to the pride festival they attended was 8.4 miles, with an interquartile range of 14.2 miles. SGM came from 67 Missouri counties. Figure 1 displays the participants' geographic distribution and shows that SGM outside urban centers were not clustered into specific counties.*

FIG. 1.

Sexual and gender minorities participant residence (Missouri only).

Exploratory aim

In an additional analysis, we calculated “quitter percent” for urban and rural SGM and non-SGM by dividing the number of former smokers in each category by the number of “ever smokers” (combined number of former and current smokers). When quit percent and SGM status were stratified by rurality (data not shown), SGM quit percent (24%) was significantly lower than that of non-SGM (42%) in rural areas (p=0.03), whereas quit percent between SGM and non-SGM participants was not different for those living in urban areas (29% and 32%, respectively). Even so, Mantel–Haenszel analysis revealed differences in rurality-adjusted odds ratios for quit prevalence and SGM status that only approached significance (p=0.08).

Discussion

This study makes a significant contribution to the current literature by having substantial numbers of both SGM and rural participants. We also had sufficient numbers to make meaningful comparisons among different SGM subgroups, furthering the import of our study. The hypotheses we posed for our primary aim were confirmed. The proportion of self-identified SGM who were current smokers (nearly 40%) was significantly higher than non-SGM (31%), and both are higher than the Missouri and general U.S. prevalence of 19–22%.11,25,26 Commensurate with the preponderance of other studies showing evidence of disparities particular to SGM subgroups,4,8,27–29 smoking proportions were particularly high in lesbian, bisexual, and transgender participants. Also consistent with our hypothesis, rural SGM current smoking was particularly notable at 45.9%. Nevertheless, in a logistic regression controlling for multiple risk factors, neither rural residence nor the interaction of SGM identity and rural residence contributed to the model.

While it seems surprising that rural residence was not predictive given the high percentage of rural SGM current smokers, this finding was likely influenced by both the small number of non-SGM (n=1145), especially those with a rural zip code (n=75), and the high proportion of current smokers among non-SGM (30.9%) compared to the general population. Although it is tempting to posit that education might be a proxy for rural residence when rural and urban residents had different proportions of educational achievement, a multicollinearity assessment with variance inflation factor values supported rurality and education as separate concepts in the model.

Our distance calculations and mapping for our secondary aim demonstrated that SGM did come from a large number of counties in rural areas. This distribution suggests that smoking among SGM has widespread relevance and indicates that urban pride festivals can reach rural SGM for targeted research and interventions.

Our final aim involved an exploratory analysis of “quit percent.” We found that rural SGM had a significantly lower percentage of former versus lifetime (ever) smokers (23%) than non-SGM (30.8–40.5%), suggesting reduced quitting as one of several possible mechanisms for increased SGM smoking, especially for rural residents. Although the rurality-adjusted odds ratios for quit percent did not reach statistical significance (p=0.06), these exploratory analyses should be considered in light of the fact that 11% (249 of the 2273) of ever smokers in our sample were from rural areas and few (n=36) were non-SGM. Ultimately, more robust and balanced group representation is needed for stronger powered analyses of these research questions in the future.

Our results and those of others suggest that SGM status remains an independent predictor of current smoking regardless of urban or rural residence. Given the historical lack of measurement of SGM status, it is not known whether SGM persons have always had a higher prevalence of smoking than non-SGM counterparts or have been more resistant to the decline in smoking prevalence in the general population. Nevertheless, analyses of smoking prevalence for SGM from our Missouri pride festival surveys in 2008, 2010,5 2011, and 2012 have shown no statistically significant difference in smoking rates in SGM attendees, while national statistics in the general population have continued to demonstrate a downward trend over this time period.30 Our findings are consistent with the one other study specifically targeting SGM in a rural state. Lee and associates8 sampled sexual minority attendees at pride festival events in West Virginia and found a current cigarette smoking proportion of 38% in the 283 respondents, which was higher than the prevalence of smoking for the state as a whole. In an older 1996 study in which 8% of the participants were from rural areas, Skinner and Otis6 found overall SGM past-month smoking rates of 35% in gay men and 43% in lesbian women, compared to the respective state's smoking prevalence of 31.7% at that time.31 Rural residents in general have similar smoking prevalence.12,32,33 There is evidence that cultural factors,34 low access to healthcare,35 targeting by the tobacco industry,34 and reduced exposure to smoke-free public spaces36–38 are likely related to rural residents' resistance to reduction in smoking rates. Given significant evidence that SGM are exposed to similar disparities,7,28,39–43 these factors may also be associated with continued high smoking rates in SGM.

This study has a number of limitations, chiefly the potential for selection bias inherent in purposive sampling. The sample was younger than the general population, so findings may better characterize adults 55 years and under. It is also evident from the high proportion of current smoking among non-SGM in our sample that these participants are not representative of the general population. Nevertheless, smoking proportions for both urban and rural SGM in our study continued to be even higher than that of non-SGM attending the same venue, consistent with other reports. Our SGM smoking proportions are also within the range reported in population-based studies,4,24,25 suggesting that our sample's SGM participants may be more representative of SGM on the whole, while our sample's non-SGM are certainly not representative of the general heterosexual population. We do assume that the SGM participants from rural counties are not the only SGM residing in those counties and may not be representative in other ways; however, the proportion of our SGM rural participants who smoke was very similar to other studies on both SGM and rural smoking. Data collectors were not trained to record the number of individuals they approached who declined filling out the survey; therefore, participation proportion of those approached cannot be calculated. As with all surveys, response bias may limit the ability to generalize to those unwilling or unable to participate. As an anonymous survey of pride festival attendees in the summer of 2012, it is possible though unlikely that an individual attending more than one festival would complete more than one survey. Compensation was not provided, and all attendees, regardless of survey participation, were offered bubbles, stickers, and ice water as booth promotions.

In conclusion, this study of a large sample of SGM corroborates other studies of higher prevalence of smoking in SGM, as well as specific within-group disparities. SGM in this study were 1.35 times more likely than non-SGM to be current smokers when controlled for age, race, education, and residence. Our study adds to the literature with the finding that not only urban but also rural SGM have a higher proportion of smoking than that of their respective geographic communities. Study of SGM continues to be limited by the lack of appropriate population-based sampling. The behavioral risk factor surveillance system (BRFSS), for example, uses a probabilistic sampling plan in which large metropolitan areas comprise a large percentage of the sample to reflect the natural state distribution; therefore, most of the survey respondents are urbanites. The BRFSS also has not yet included sexual orientation on the national survey.16 Currently, 25 states include SGM status on their BRFSS,44 but those with longer history and more comprehensive questions tend to contain the cities most progressive on SGM rights issues,45 and therefore again may not be representative.

Overall, given the low prevalence of SGM, the number of individuals reporting in any 1 year of a population-based survey is too small for meaningful analysis. For example, Fredriksen-Goldsen et al.46 used 8 years of Washington state BRFSS data to have a sample size of 1531 from 97,670 participants. The National Health Interview Survey15 and the National Adult Tobacco Survey14 have recently begun to ask sexual identity questions (though not yet gender identity), and the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey47 has behavioral questions that can identify same-sex sexual activity, though not identification. Although these surveys may eventually hold some hope of achieving large enough sample sizes of sexual minorities, most studies still must aggregate data over years to have meaningful numbers, a practice that introduces considerable error as social norms change over time.48 Attempts to meaningfully analyze minority subgroups such as rural SGM will remain challenging.

Despite its sampling limitations, our study achieved approximately double the number of SGM respondents than the Washington state BRFSS accumulated over 8 years, and allowed for rural–urban comparisons not possible in other study designs. There is, therefore, a continued role for a purposive design that allows for a natural “oversampling” of hard-to-reach population groups. Novel approaches to recruitment and sampling are sorely needed. Our study methods demonstrate a viable method of recruiting substantial numbers of rural participants in accessible locations, and may be easily adapted to and modified for other regions of the county in efforts to reach rural SGM populations.

The identification of very high prevalence groups for tobacco use (both SGM and pride attendees in general) presents a number of important policy implications. Individual and policy-level interventions should target and be evaluated in both urban and rural SGM, as patterns and effects may have geographic variance. Particularly, the effects of tobacco restrictions and tobacco-free places deserve more investigation7 and may be particularly important for SGM in rural areas where such policies continue to be less common.36 Nuances and correlates of smoking such as nondaily (social) smoking, age at first cigarette, and nicotine dependence measures are associated with particular health effects of smoking and degree of effort needed to quit.49–53 These measures have only begun to be addressed in SGM populations and deserve further study in subgroups as well. Qualitative research also has an important role; for example, insights from both urban and rural SGM who successfully quit smoking could elucidate nuanced cultural and social factors influencing smoking cessation and help design targeted interventions. The perspectives and engagement of both urban and rural SGM people should be incorporated into public health interventions. Collaborations among rural health, state policy, and SGM community organizations are ideal for addressing the intersection of the rural-SGM tobacco disparity.

Acknowledgments

Financial support for the Out, Proud, and Healthy project was provided by the Missouri Foundation for Health (11-0439-TRD-11). The Missouri Foundation for Health also provided funding for the collection of the 2011 County Level Survey data. Dr. Bennett's time was supported in part by a grant from National Center for Advancing Translation Sciences, National Institutes of Health (no. KL2TR000116.)

The authors wish to acknowledge the work of the OPAH project staff members, Ellen Hahn, PhD, RN; Mary Kay Rayans, PhD; and Jane Gokun, PhD, for review of analysis and recommendations, as well as Karen Roper, PhD; Cathy Hardin; and Kelly Werner of the University of Kentucky for editorial assistance.

Disclaimer

Findings have been presented at the North American Primary Care Research Group Annual Conference, Ottawa, Ontario, Canada, November 2013.

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist for any of the authors.

Percent Missouri residence here defined by zip code differs slightly from the self-reported state variable used for analyses in tables.

References

- 1.Institute of Medicine (U.S.) Committee on Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Health Issues and Research Gaps and Opportunities: The Health of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender People. 2011. Washington, DC, National Academies Press; Available at www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK64806/pdf/TOC.pdf (last accessed July31, 2014) [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mayer KH, Bradford JB, Makadon HJ, et al. : Sexual and gender minority health: What we know and what needs to be done. Am J Public Health 2008;98:989–995 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Conron KJ, Mimiaga MJ, Landers SJ: A population-based study of sexual orientation identity and gender differences in adult health. Am J Public Health 2010;100:1953–1960 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lee JGL, Griffin GK, Melvin CL: Tobacco use among sexual minorities in the USA, 1987 to may 2007: A systematic review. Tob Control 2009;18:275–282 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McElroy JA, Everett KD, Zaniletti I: An examination of smoking behavior and opinions about smoke-free environments in a large sample of sexual and gender minority community members. Nicotine Tob Res 2011;13:440–448 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Skinner WF, Otis MD: Drug and alcohol use among lesbian and gay people in a southern U.S. Sample. J Homosex 1996;30:59–92 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Blosnich J, Lee JG, Horn K: A systematic review of the aetiology of tobacco disparities for sexual minorities. Tob Control 2013;22:66–73 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lee JGL, Goldstein AO, Ranney LM, et al. : High tobacco use among lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations in West Virginian bars and community festivals. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2011;8:2758–2769 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.U.S. Department of Agriculture Economic Research Service: USDA state fact sheets: Missouri 2013. Available at www.ers.usda.gov/data-products/state-fact-sheets/state-data.aspx?StateFIPS=29&StateName=Missouri#.Ur9Nv7TxjjV (updated November 6, 2013; last accessed December28, 2013)

- 10.Health Resources and Services Administration: Defining the rural population. Available at www.hrsa.gov/ruralhealth/policy/definition_of_rural.html (last accessed December28, 2013)

- 11.Missouri Department of Health and Senior Services: Missouri county level study: Tobacco use in Missouri adults 2011. Available at http://health.mo.gov/data/mica/County_Level_Study_12/header.php?cnty=929&profile_type=4&chkBox=C (last accessed August12, 2013)

- 12.Sorg A, Shelton S, Harris J, Luke D: Looking Beyond the Urban Core: Tobacco-Related Disparities in Rural Missouri. St. Louis, MO: Center for Tobacco Policy Research, Washington University, 2011 [Google Scholar]

- 13.Out Proud and Healthy in Missouri: LGBT Tobacco Project. Available at www.outproudandhealthy.org/research-2/tobacco/ (last accessed September12, 2013)

- 14.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: National adult tobacco survey. Available at www.cdc.gov/tobacco/data_statistics/surveys/nats/ (updated April 4, 2014; last accessed June4, 2014)

- 15.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: National health interview survey 2014. Available at www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhis.htm (updated May 12, 2014; last accessed June4, 2014)

- 16.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: Behavioral risk factor surveillance. Available at www.cdc.gov/brfss/ (updated May 8, 2014; last accessed June4, 2014)

- 17.Rural Health Research Center: Rural urban commuting area codes: University of Washington; Available at http://depts.washington.edu/uwruca/index.php (last accessed October4, 2013) [Google Scholar]

- 18.U.S. Department of Agriculture Ecomonic Research Service: Rural definitions: Overview. Available at www.ers.usda.gov/datafiles/Rural_Definitions/StateLevel_Maps/MO.pdf (last accessed August12, 2013)

- 19.Beyer KMM, Schultz AF, Rushton G: Using zip codes as geocodes in cancer research. In: Geocoding Health Data: The Use of Geographic Codes in Cancer Prevention, Research, and Practice. Edited by Rushton G. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press, 2008, pp. 37–68 [Google Scholar]

- 20.Soares NS, Johnson AO, Patidar N: Geomapping telehealth access to developmental-behavioral pediatrics. Telemed J E Health 2013;19:585–590 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Economic Research Service: Rural-urban continuum codes: United States Department of Agriculture. Available at www.ers.usda.gov/data-products/rural-urban-continuum-codes.aspx#.Ut_tT7ROmUk (updated May 10, 2013; last accessed January14, 2014)

- 22.Diamant AL, Wold C, Spritzer K, Gelberg L: Health behaviors, health status, and access to and use of health care: A population-based study of lesbian, bisexual, and heterosexual women. Arch Fam Med 2000;9:1043–1051 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kann L, Olsen EO, McManus T, et al. : Sexual identity, sex of sexual contacts, and health-risk behaviors among students in grades 9–12—youth risk behavior surveillance, selected sites, United States, 2001–2009. MMWR Surveill Summ 2011;60:1–133 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.McCabe SE, Hughes TL, Boyd CJ: Substance use and misuse: Are bisexual women at greater risk? J Psychoactive Drugs 2004;36:217–225 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: Behavioral risk factor surveillance system: Prevalence and trends data—nationwide tobacco use 2011. Available at http://apps.nccd.cdc.gov/brfss/display.asp?cat=TU&yr=2011&qkey=8161&state=UB (last accessed February11, 2013)

- 26.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: Report: Smoking and tobacco use 2011. Available at www.cdc.gov/tobacco/data_statistics/fact_sheets/adult_data/cig_smoking/#state (last accessed August12, 2013)

- 27.Dilley JA, Maher JE, Boysun MJ, et al. : Response letter to: Tang H, Greenwood GL, Cowling DW, Lloyd JC, Roeseler AG, Bal DG. Cigarette smoking among lesbians, gays, and bisexuals: How serious a problem? Cancer Causes Control 2005;16:1133–1134 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dilley JA, Spigner C, Boysun MJ, et al. : Does tobacco industry marketing excessively impact lesbian, gay and bisexual communities? Tob Control 2008;17:385–390 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tang H, Greenwood GL, Cowling DW, et al. : Cigarette smoking among lesbians, gays, and bisexuals: How serious a problem? Cancer Causes Control 2004;15:797–803 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: Early release of selected estimates based on data from the January–September 2013 National Health Interview Survey: Current cigarette smoking. 2014. Report No. 3/2014.

- 31.Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System: Prevalence and trends data: Adults who are current smokers: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 1996. Available at http://apps.nccd.cdc.gov/brfss/list.asp?cat=TU&yr=1996&qkey=4396&state=All (last accessed August13, 2013)

- 32.Stoops WJ, Dallery J, Fields NM, Nuzzo PA, Schoenberg NE, Martin CA, Casey B, Wong CJ: An internet-based abstinence reinforcement smoking cessation intervention in rural smokers. Drug Alcohol Depend 2009;105:56–62 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Vander Weg MW, Cunningham CL, Howren MB, Cai X: Tobacco use and exposure in rural areas: Findings from the behavioral risk factor surveillance system. Addict Behav 2011;36:231–236 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hutcheson TD, Greiner KA, Ellerbeck EF, et al. : Understanding smoking cessation in rural communities. J Rural Health 2008;24:116–124 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shi L, Macinko J, Starfield B, et al. : Primary care, social inequalities and all-cause, heart disease and cancer mortality in us counties: A comparison between urban and non-urban areas. Public Health 2005;119:699–710 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ferketich AK, Liber A, Pennell M, et al. : Clean indoor air ordinance coverage in the appalachian region of the United States. Am J Public Health 2010;100:1313–1318 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hahn EJ, Ashford KB, Okoli CT, et al. : Nursing research in community-based approaches to reduce exposure to secondhand smoke. Annu Rev Nurs Res 2009;27:365–391 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rayens MK, York NL, Adkins SM, et al. : Political climate and smoke-free laws in rural kentucky communities. Policy Polit Nurs Prac 2012;13:90–97 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Balsam KF, Beadnell B, Riggs KR: Understanding sexual orientation health disparities in smoking: A population-based analysis. Am J Orthopsychiat 2012;82:482–493 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Heck JE, Sell RL, Sheinfeld GS: Health care access among individuals involved in same-sex relationships. Am J Public Health 2006;96:1111–1118 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Meyer IH: The right comparisons in testing the minority stress hypothesis: Comment on Savin-Williams, Cohen, Joyner, and Rieger (2010). Arch Sex Behav 2010;39:1217–1219 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rostosky SS, Riggle EDB, Gray BE, Hatton RL: Minority stress experiences in committed same-sex couple relationships. Prof Psychol-Res Pr 2007;38:392–400 [Google Scholar]

- 43.Smith EA, Thomson K, Offen N, Malone RE: “If you know you exist it's just marketing poison”: Meanings of tobacco industry targeting in the lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender community. Am J Public Health 2008;98:996–1003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.The Fenway Institute Center for Population Research in LGBT Health: 25 States have included sexual orientation items in the BRFSS. 2013. Available at http://lgbtpopulationcenter.org/2013/07/25-states-have-included-sexual-orientation-items-in-the-brfss/ (last accessed June4, 2014)

- 45.Wilson R: Study: Big cities most likely to have progressive gay-rights laws. The Washington Post [Internet]. 2013. Available at www.washingtonpost.com/blogs/govbeat/wp/2013/11/19/study-big-cities-most-likely-to-have-progressive-gay-rights-laws/ (last accessed June4, 2014)

- 46.Fredriksen-Goldsen KI, Kim HJ, Barkan SE, et al. : Health disparities among lesbian, gay, and bisexual older adults: Results from a population-based study. Am J Public Health 2013;103:1802–1809 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: National health and nutrition examination survey Atlanta GA2011–2012. Available at www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes/nhanes2011-2012/questionnaires11_12.htm (updated February 21, 2014; last accessed June4, 2014)

- 48.Gates G: Demographics and LGBT health. J Health Soc Behav 2013;54:72–74 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Everett SA, Warren CW, Sharp D, et al. : Initiation of cigarette smoking and subsequent smoking behavior among U.S. High school students. Prev Med 1999;29:327–333 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hammond D: Smoking behaviour among young adults: Beyond youth prevention. Tob Control 2005;14:181–185 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Oh DL, Heck JE, Dresler C, et al. : Determinants of smoking initiation among women in five european countries: A cross-sectional survey. BMC Public Health 2010;10:74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Schane RE, Ling PM, Glantz SA: Health effects of light and intermittent smoking: A review. Circulation 2010;121:1518–1522 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Smit ES, Fidler JA, West R: The role of desire, duty and intention in predicting attempts to quit smoking. Addiction 2011;106:844–851 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]