Abstract

Early recognition of colorectal cancer (CRC) in young patients without known genetic predisposition is a challenge, and clinicopathologic features at time of presentation are not well described. We conducted the current study to review these features in a large population of patients with young-onset CRC (initial diagnosis at age ≤50 yr without established risk factors).

We reviewed the records of all patients aged 50 years or younger diagnosed with a primary CRC at our institution between 1976 and 2002. Patients with inflammatory bowel disease, polyposis syndromes, or a known genetic predisposition for CRC were excluded. Data regarding clinical and pathologic features at time of initial presentation were abstracted by trained personnel.

We identified 1025 patients, 585 male. Mean age at presentation was 42.4 years (standard deviation 6.4). Eight hundred eighty-six (86%) patients were symptomatic at time of diagnosis. Clinical features in symptomatic patients included rectal bleeding (51%), change in bowel habits (18%), abdominal pain (32%), weight loss (13%), nausea/vomiting (7%), melena (2%), and other (26%). Evaluation of asymptomatic patients was pursued with findings of anemia (14%), positive fecal occult blood test (7%), abdominal mass (2%), mass on digital rectal exam (2%), and other (80%). Site of primary tumor was colonic in 51% and rectal in 49%. Synchronous malignant lesions were noted in 1%. Mucinous and signet cell histology was seen in 11% and 2%, respectively. Tumor grade distribution was grade 1 (2%), grade 2 (54%), grade 3 (34%), and grade 4 (7%). The stage distribution was stage I (13%), stage II (21%), stage III (32%), and stage IV (34%).

To our knowledge, the current study is the largest cohort of young-onset CRC patients with no known genetic predisposition for disease. Most patients were symptomatic, had left-colon or rectal cancers and presented with more advanced stage disease. Our findings should promote increased awareness and the aggressive pursuit of symptoms in otherwise young, low-risk patients, as these symptoms may represent an underlying colorectal malignancy.

INTRODUCTION

In the United States, colorectal cancer (CRC) is the third most commonly diagnosed cancer and the second leading cause of cancer death2,11. Rates of CRC from the 2001–2003 Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) national cancer registry database estimate that up to 6% of the United States population will develop CRC at some point in their lifetime16. Overall, the mean age of diagnosis for cancers of the colon and rectum is 71 years16. Historically, the onset of CRC in younger patients was thought to be rare, but recent reports14,15 suggest that as many as 7% of patients who develop CRC are under 40 years of age at the time of diagnosis.

Select groups of young patients are known to be at increased CRC risk, such as those with inflammatory bowel disease, hereditary nonpolyposis colon cancer, and polyposis syndromes of the gastrointestinal tract. In this high-risk population, early screening has been shown to reduce mortality from CRC10. For young patients who develop CRC, but have no known predisposing genetic risk factors, late diagnosis and poor outcomes may result from the clinician’s failure to consider the possibility of malignant disease in the differential diagnosis.

To our knowledge based on our review of the literature, no large-scale studies have been performed to evaluate young-onset CRC in patients without known genetic predisposition. Moreover, in published series on CRC in younger patients, controversy exists regarding clinical presentation, pathologic features, and stage at presentation1,3,4,7,13,17. Thus, we conducted the current study to determine the clinical and pathologic features and stage at presentation in a large population of young patients with colorectal malignancy who had no known predisposing genetic risk factors at the time of diagnosis.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

We conducted a retrospective review of all patients between 18 and 50 years of age diagnosed with a primary CRC at our institution between 1976 and 2002. The age of 50 years was used as a cutoff to define “young-onset” because that age is recommended by most medical societies as the time to begin screening for sporadic CRC. Patients were excluded from analysis if they had hereditary non-polyposis colon cancer, inflammatory bowel disease, polyposis syndrome, or had a positive family history for these conditions. Patients with a positive family history for sporadic colorectal cancer were not excluded from analysis. This study was approved by our Institutional Review Board.

Trained nurse abstractors extracted clinical and pathologic features from the patient record. The location of tumors in the colon was defined as right sided (cecum, ascending colon, hepatic flexure, transverse colon, and splenic flexure) or left sided (descending colon, sigmoid colon), or rectum. Rectal location of lesions was confirmed using pathology reports. Synchronous cancers were considered present if a secondary lesion was found away from the primary tumor at the time of diagnosis or within 1 year. Tumors were classified according to the tumor-node-metastasis (TNM) staging system; if stage could not be determined patients were excluded from analysis.

Statistics

Data were summarized using frequencies and percentages for all categorical variables, and means and standard deviations for all continuous variables. We determined whether distributions of demographic and clinical characteristics differed in patients with colon compared to rectal cancer using chi-square tests for categorical variables and t-tests for continuous variables. All statistical tests were 2-sided, and all analyses were carried out using the SAS (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC) software system.

RESULTS

During the study period, 31,348 patients were seen at our institution with the diagnosis of colorectal cancer. Of these, 1025 patients were aged 50 years or younger and represent the young-onset cohort. Of this cohort, 181 patients had a first-degree relative, and 79 had a second-degree relative, with colorectal cancer. Mean age at presentation was 42.4 years (SD 6.4), and 585 of these patients were male. Demographic and clinical features of this cohort, separated by rectal or colon location, are outlined in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Demographic and Clinical Features*

| Feature | Colon Cancer (n = 524)† | Rectal Cancer (n = 499)‡ | p Value§ |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | |||

| Male | 275 (52.5) | 308 (61.7) | 0.003 |

| Female | 249 (47.5) | 191 (38.3) | |

| Mean age (SD, minimum) | 42.6 (6.2, 17.9) | 42.2 (6.6, 17.8) | 0.26 |

| Symptomatic at presentation | 434 (82.8) | 450 (90.2) | <0.001 |

| Presenting clinical features at first diagnosis|| | |||

| Rectal bleeding | 176 (33.6) | 344 (68.9) | <.001 |

| Abdominal pain | |||

| Acute | 22 (4.2) | 1 (0.2) | <.001 |

| Chronic | 236 (45.0) | 74 (14.8) | <.001 |

| Change in bowel habits | 77 (14.7) | 108 (21.6) | 0.004 |

| Diarrhea | 60 (11.5) | 75 (15.0) | 0.09 |

| Positive fecal blood test | 28 (5.3) | 18 (3.6) | 0.18 |

| Rectal Pain | 6 (1.1) | 66 (13.2) | <.001 |

| Bloating | 51 (9.7) | 24 (4.8) | 0.003 |

| Constipation | 40 (7.6) | 46 (9.2) | 0.36 |

| Weight loss | 74 (14.1) | 61 (12.2) | 0.37 |

| Nausea or vomiting | 55 (10.5) | 13 (2.6) | <.001 |

| Melena | 10 (1.9) | 10 (2.0) | 0.91 |

| Other | 153 (29.2) | 108 (21.6) | 0.006 |

Values presented as number (%) unless otherwise indicated. Two subjects with both colon and rectal cancer at initial diagnosis were excluded from table.

Includes cecum (ICD-O C18.0), ascending colon (C18.2), hepatic flexure (C18.3), transverse colon (C18.4), splenic flexure (C18.5), descending colon (C18.6), and sigmoid C18.7).

Includes rectosigmoid junction (C19.9) and rectum (C20.9).

Chi-square tests for categorical variables and t-tests for continuous variables.

Numbers total more than 100% because subjects were allowed to have multiple presenting features.

Eight hundred eighty-six (86%) patients were symptomatic at the time of diagnosis. Patients with rectal cancer were more likely to be male (62% vs. 53%, p = 0.003) and to present with symptoms (90% vs. 83%, p < 0.001), and less likely to be stage 4 at the time of diagnosis (26% vs. 41%, p < 0.001) than patients with colon cancer. Patients with rectal cancer were also more likely to report rectal bleeding (69% vs. 34%, p < 0.001), changes in bowel habits (22% vs. 15%, p < 0.001), and rectal pain (13% vs. 1%, p < 0.001), and less likely to report acute abdominal pain (0% vs. 4%, p < 0.001), chronic abdominal pain (15% vs. 45%, p < 0.001), bloating (5% vs. 10%, p < 0.001), and nausea or vomiting (3% vs. 11%, p < 0.001) compared with patients with colon cancer. Of the 139 asymptomatic patients, evaluations were pursued with the finding of anemia in 19 (14%), positive fecal occult blood test in 10 (7%), abdominal mass in 3 (2%), mass on digital rectal exam in 3 (2%), and other in 110 (80%).

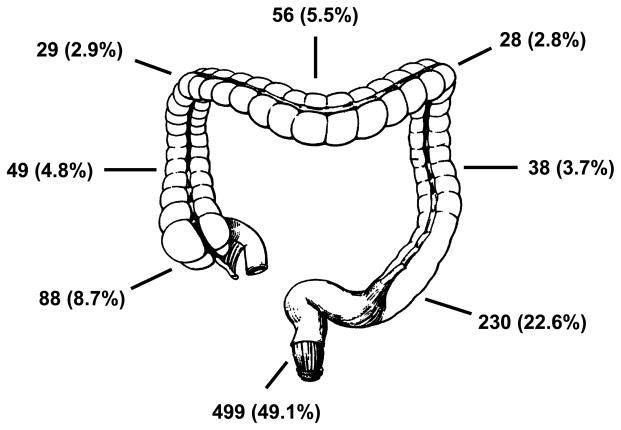

Pathologic features of this cohort are outlined in Table 2. Synchronous malignant lesions were noted in 11 patients (1%). Figure 1 details the specific subsite location of tumors in the colorectum. The most common site of primary tumor was the rectum (49.1%), followed by left colon (29.1%) and right colon (21.9%). Mucinous and signet cell histology was seen in 11% and 2%, respectively. Most tumors were pathologic grade 2 (54%) or grade 3 (34%). The majority of tumors had either local (stage III = 32%) and or distant (stage IV = 34%) spread upon presentation.

TABLE 2.

Pathologic Features*

| Feature | Colon Cancer (n = 524)† | Rectal Cancer (n = 499)‡ | p Value§ |

|---|---|---|---|

| Synchronous malignant lesions | 7 (1.4) | 2 (0.4) | 0.11 |

| Grade | |||

| Grade 1 | 9 (1.7) | 12 (2.4) | 0.25 |

| Grade 2 | 267 (51.0) | 282 (56.5) | |

| Grade 3 | 191 (36.5) | 158 (31.7) | |

| Grade 4 | 43 (8.2) | 31 (6.2) | |

| Unknown grade | 14 (2.7) | 16 (3.2) | |

| Pathologic staging | |||

| Stage 1 | 42 (8.0) | 95 (19.0) | <.001 |

| Stage 2 | 110 (21.0) | 99 (19.8) | |

| Stage 3 | 155 (29.6) | 174 (34.9) | |

| Stage 4 | 217 (41.4) | 131 (26.3) | |

Values presented as number (%). Two subjects with both colon and rectal cancer at initial diagnosis were excluded from table.

Includes cecum (ICD-O C18.0), ascending colon (C18.2), hepatic flexure (C18.3), transverse colon (C18.4), splenic flexure (C18.5), descending colon (C18.6), and sigmoid (C18.7).

Includes rectosigmoid junction (C19.9) and rectum (C20.9).

Chi-square test.

FIGURE 1.

Specific subsite locations of tumors in the colorectum.

DISCUSSION

Most studies examining the clinical and pathologic features of young patients with CRC do not discern those who have known genetic risk factors from those who do not. In the current study we aimed to characterize clinical and pathologic features in a unique population of young patients with CRC who had no known risk factors at the time of diagnosis. The main findings of our study are that a majority of young-onset CRC patients were symptomatic at the time of presentation, had predominantly left-sided lesions (rectal and left colon), and presented at a relatively late stage in their disease.

Clinical features at presentation in our cohort are similar to those found in other published series on young-onset CRC. In a review of 55 articles examining patients with CRC aged younger than 40 years, O’Connell and colleagues14 found that the 2 most common symptoms at presentation were rectal bleeding (46%) and abdominal pain (55%). In our population, patients with rectal cancer most commonly presented with rectal bleeding and change in bowel habits, while patients with colon cancer were more likely to present with chronic abdominal pain, nausea and vomiting, and rectal bleeding.

Most studies on young-onset CRC that examine histologic features note a higher prevalence of mucinous or poorly differentiated tumors, including signet ring type. Using the SEER national cancer database, O’Connell et al13,14 compared colon cancer patients between the ages of 20 and 40 years to a group of patients between the ages of 60 and 80 years. Regarding histology, they found that younger patients had more mucinous (15.7% vs. 11.5%) and signet cell (3.8% vs. 0.8%) tumors compared to the older group. Moreover, they found that younger patients had a statistically significant higher percentage of poorly differentiated (27.3% vs 17.2%) and anaplastic (1.6% vs. 0.7%) tumors compared to the older group.

In our cohort, the rate of mucinous (11%) and signet cell (2%) subtypes were comparable to this. In our cohort the breakdown by decade of mucinous histology was the following: 10–20 year olds (33.3%), 20–30 year olds (16.7%), 30–40 year olds (13.7%), and 40–50 year olds (9.29%). Based on these findings we believe that younger patients with CRC have a higher rate of mucinous histology compared to older (aged >50 yr) patients. Both of these histologic features, along with tumor infiltrating lymphocytes, are common among tumors that arise due to defective DNA mismatch repair (MMR). Defective DNA MMR is the genetic or epigenetic defect that leads to the hereditary CRC associated with Lynch syndrome and germline mutations in the MMR genes, or to the older-onset CRC secondary to DNA MMR inactivation from hypermethylation of the MLH1 promoter. Between 17% and 31% of young-onset CRC will exhibit defective DNA MMR. These tumors have a distinct clinical picture of tending to arise in the right side of the colon, with a better prognosis than CRC with intact DNA MMR. DNA MMR status is not available in either the current study or that of O’Connell et al, although in the current study we did exclude patients with young-onset CRC who had a diagnosis of Lynch syndrome.

We found that a majority of our patients were diagnosed with advanced disease at the time of presentation, which is consistent with other reports in the literature4,6,8,14,17. A 2006 analysis of over 42,000 patients from the National Program of Cancer Registries and SEER databases revealed that persons aged younger than 50 years presented with less localized (29.7% vs. 35.1%) and more distant (21.9% vs. 16.0%) disease compared with older adults5. Moreover, in that review, proximal colon cancers were less frequent in persons aged younger than 50 years than among older adults (32.1% vs. 42.6%), and age-adjusted incidence rates were highest for rectal cancers in persons aged younger than 50 years. In our cohort, rectal cancers were more common than proximal colon cancers (49.1% vs. 21.9%), and 66% of patients presented with either stage III or IV disease.

Late presentation raises the issue of why diagnosis is not made earlier. Several reports published on young-onset CRC discuss the issue of delay in diagnosis. We were unable to address this because of the referral nature of our practice and the difficulty of determining an accurate date on which symptoms began for most patients. Others14 report that delays are a result of patient-related factors, such as lack of access, ignoring symptoms, and patient denial, and physician-related factors, such as misdiagnosis. A study9 that specifically examined physician-related factors in late diagnosis found that at least 50% of patients had a physician-related delay in diagnosis.

The current study was intentionally designed to focus on the clinicopathologic features of young-onset CRC patients in order to develop a profile of this subgroup that may facilitate early recognition of this entity. One of the major strengths of this study is that the results confirm that in a large group of “low-risk” young patients with CRC symptoms (such as rectal bleeding, change in bowel habits, and chronic abdominal pain), these symptoms should raise suspicion of an underlying colorectal lesion. Moreover, the detailed and complete medical record kept of cancer patients allowed for very accurate and thorough reviews of clinical and pathologic features.

One limitation of the current study is that it is a referral-based population and not a population-based cohort. Despite this, most of the population-based studies revealed similar findings to ours regarding clinical presentation and pathologic features. Because of our tertiary-care setting, the overall percentage of patients identified as being symptomatic may be biased, but chart abstraction in terms of clinical presentation focused on the symptoms the patients went to see a doctor for, whether it was at our institution initially or at another facility before referral. Another limitation to our study is that many patients in this cohort have not yet undergone testing for microsatellite instability, either because clinicians did not order it, or because patients presented with their disease before testing was available.

Our future direction regarding this database is to identify and test patients from this cohort who have a strong potential (fulfill Amsterdam Criteria) for being positive for the gene defects seen in patients with hereditary non-polyposis colon cancer to see if this biases our current results. It is our impression that a large majority of this cohort will test negative and remain without any known genetic risk factor for young-onset CRC. It may be that with more extensive genetic analysis of this cohort’s pathology, a yet “undiscovered genetic defect” will be elucidated that could lead to the identification of a new high-risk group of patients susceptible to young-onset CRC. Centers in many parts of the world are actively investigating this possibility, and a group in France has recently published data suggesting that a tumor suppressor gene located on chromosome 14 might have an important role in microsatellite stable colon carcinogenesis12. Only through a discovery of this type, and clinical awareness, can the morbidity and mortality of these young patients be improved.

Conclusion

The uncommon occurrence of CRC in young adults with no predisposing genetic risk factors demands maintaining a high index of suspicion when people aged 50 years or younger present with symptoms of abdominal pain and hematochezia. In the current study we report data from what is, to our knowledge, the largest cohort of young-onset CRC patients not known to fall into any high-risk group. Based on our findings, most patients are symptomatic at the time of presentation, with the majority having rectal bleeding and chronic abdominal pain. The majority of tumors were located in the sigmoid colon and rectum, which can easily be reached with flexible sigmoidoscopy. Our findings should promote increased awareness and aggressive pursuit of symptoms in young patients with the possibility that these symptoms may represent an underlying colorectal malignancy.

Abbreviations

- CRC

colorectal cancer

- MMR

mismatch repair

- SEER

Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results

References

- 1.Adloff M, Arnaud JP, Bergamaschi R, Schloegel M. Synchronous carcinoma of the colon and rectum: prognostic and therapeutic implications. Am J Surg. 1989;157:299–302. doi: 10.1016/0002-9610(89)90555-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.American Cancer Society. Cancer Facts and Figures 2002 (Publication 02-250M-No 5008.02) New York: American Cancer Society Surveillance Research; 2002. pp. 20–26. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chiang JM, Chen MC, Changchien CR, Chen JS, Tang R, Wang JY, Yeh CY, Fan CW, Tsai WS. Favorable influence of age on tumor characteristics of sporadic colorectal adenocarcinoma: patients 30 years of age or younger may be a distinct patient group. Dis Colon Rectum. 2003;46:904–910. doi: 10.1007/s10350-004-6683-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Domergue J, Ismail M, Astre C, Saint-Aubert B, Joyeux H, Solassol C, Pujol H. Colorectal carcinoma in patients younger than 40 years of age: Montpellier Cancer Institute experience with 78 patients. Cancer. 1998;61:835–840. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19880215)61:4<835::aid-cncr2820610432>3.0.co;2-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fairley TL, Cardinez CJ, Martin J, Alley L, Friedman C, Edwards B, Jamison P. Colorectal cancer in U.S. adults younger than 50 years of age, 1998–2001. Cancer. 2006;107(Suppl 5):1153–1161. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Griffin PM, Liff JM, Greenberg RS, Clark WS. Adenocarcinomas of the colon and rectum in persons under 40 years old. A population-based study. Gastroenterology. 1991;100:1033–1040. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(91)90279-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Heimann TM, Oh C, Aufses AH., Jr Clinical significance of rectal cancer in young patients. Dis Colon Rectum. 1989;32:473–476. doi: 10.1007/BF02554500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Isbister WH, Fraser J. Large-bowel cancer in the young: a national survival study. Dis Colon Rectum. 1990;33:363–366. doi: 10.1007/BF02156258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jarniven HJ, Turunen MJ. Colorectal carcinoma before 40 years of age; prognosis and predisposing conditions. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1984;19:634–638. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jarvinen HJ, Mecklin JP, Sistonen P. Screening reduces colorectal cancer rate in families with hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer. Gastroenterology. 1995;108:1405–1411. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(95)90688-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Miller B, Kolonel L, Bernstein L, et al., editors. Racial/Ethnic Patterns of Cancer in the United States 1988–1992 (NIH Publication No. 96–4104) Bethesda, MD: National Cancer Institute; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mourra N, Zeitoun G, Buecher B, Finetti P, Arnaud L, Adelaid J, Birnbaum D, Thomas G, Olschwang S. High frequency of chromosome 14 deletion in early-onset colon cancer. Dis Colon Rectum. 2007;50:1881–1886. doi: 10.1007/s10350-007-9040-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.O’Connell JB, Maggard MA, Liu JH, Etzioni DA, Livinston EH, Ko CY. Do young colon cancer patients have worse outcomes? World J Surg. 2004;28:558–562. doi: 10.1007/s00268-004-7306-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.O’Connell JB, Maggard MA, Livingston EH, Yo CK. Colorectal cancer in the young. Am J Surg. 2004;187:343–348. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2003.12.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.O’Connell JB, Maggard MA, Liu JH, Etzioni DA, Ko CY. Rates of colon and rectal cancers are increasing in young adults. Am Surg. 2003;69:866–872. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ries LAG, Melbert D, Krapcho M, Mariotto A, Miller BA, Feuer EJ, Clegg L, Horner MJ, Howlader N, Eisner MP, Reichman M, Edwards BK, editors. SEER Cancer Statistics Review, 1975–2004. Bethesda, MD: National Cancer Institute; http://seer.cancer.gov/csr/1975_2004/, based on November 2006 SEER data submission, posted to the SEER website 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Taylor MC, Pounder D, Ali-Ridha NH, Bodurtha A, MacMullin EC. Prognostic factors in colorectal carcinoma of young adults. Can J Surg. 1988;31:150–153. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]