Abstract

Introduction

Sympathetic nervous system hyperactivity is common after subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH). We sought to determine whether uncontrolled prolonged heart rate elevation is a risk factor for adverse cardiopulmonary events and poor outcome after SAH.

Methods

We prospectively studied 447 SAH patients between March 2006 and April 2012. Prior studies define prolonged elevated heart rate (PEHR) as heart rate >95 beats/min for >12 hours. Major adverse cardiopulmonary events were documented according to predefined criteria. Global outcome at 3 months was assessed with the modified Rankin Scale (mRS).

Results

175 (39%) patients experienced PEHR. Nonwhite race/ethnicity, admission Hunt-Hess grade ≥4, elevated APACHE-2 physiological subscore, and modified Fisher score were significant admission predictors of PEHR, whereas documented pre-hospital beta-blocker use was protective. After controlling for admission Hunt-Hess grade, Cox regression using time-lagged covariates revealed that PEHR onset in the previous 48 hours was associated with an increased hazard for delayed cerebral ischemia, myocardial injury and pulmonary edema. PEHR was associated with 3-month poor outcome (mRS 4-6) after controlling for known predictors.

Conclusions

PEHR is associated with major adverse cardiopulmonary events and poor outcome after SAH. Further study is warranted to determine if early sympatholytic therapy targeted at sustained heart rate control can improve outcome after SAH.

Keywords: heart rate, subarachnoid hemorrhage, cardiopulmonary complications, functional outcome

Introduction

Aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH) is a devastating illness that causes substantial morbidity and mortality. Sympathetic nervous system hyperactivity is common after (SAH), and typically manifests as hypertension with sinus tachycardia. 1-4 The catecholamine surge that occurs after SAH has been linked to neurogenic cardiac injury, which can result in ECG abnormalities, 5 cardiac troponin elevations, 6 reduced left ventricular performance, 7 pulmonary edema, 8 atrial fibrillation/flutter, 9 sinus tachycardia, 3 and stunned myocardium and frank cardiogenic shock. 10 Several studies have documented a link between sympathetic activation, evidence of cardiac injury, and poor outcome after SAH. 2,4,11-13

Prolonged heart rate elevation has been shown to be a risk factor for major cardiac events among cardiothoracic ICU patients, 14 whereas prophylactic beta-blockade reduces the frequency of myocardial infarction in high-risk patients undergoing surgical procedures. 15 Agents that exclusively reduce cardiac afterload, such as nicardipine, sodium nitroprusside, and hydralazine, are commonly used to control blood pressure during the acute phase of SAH when the risk of aneurysm rebleeding is greatest. 16 In this study, we sought to explore the potential rationale for sympatholytic therapy directed at heart rate control as a strategy to reduce complications and improve outcome after SAH by determining whether prolonged heart rate elevation (PEHR) during the pre and post-operative period is associated with major adverse cardiac events or 3-month death or disability.

Methods

Study Population

We prospectively enrolled 512 consecutive SAH patients into the Columbia University SAH Outcomes Project between March 2006 and April 2012. The present analysis included 447 patients, excluding 65 patients either because of technical failures or late admission (after SAH day 2) to our ICU. The study was approved by the Columbia University Medical Center Institutional Review Board; in all cases written informed consent was obtained from the patient or a surrogate. The diagnosis of SAH was established by admission (CT) or by xanthochromia of cerebrospinal fluid if the initial CT scan was nondiagnostic. Patients with secondary SAH related to trauma, rupture of an AVM, or other causes and age < 18 years were not enrolled in the study.

Clinical Management

Clinical management conformed to American Heart Association guidelines. 16 All patients underwent serial ECG on admission. Cardiac troponin I (cTI) testing was performed on admission and thereafter when clinically indicated (e.g., ECG changes, cardiovascular instability, or during induced hypertension). All patients received oral nimodipine and intravenous hydration with 0.9% saline with supplemental fluids as needed to maintain equal fluid balance and a normal central venous pressure (5-10 mm Hg). Hypertensive hypervolemic therapy (HHT) was initiated for symptomatic vasospasm or when severe angiographic vasospasm was diagnosed in poor grade patients by increasing systolic blood pressure (SBP) from 180 to 220 mmHg. 17

Data Collection

We recorded demographics, past medical history, baseline clinical status, imaging results, as well as treatment and complications during hospitalization as described previously. 18 Hourly heart rate (HR) data was queried from the electronic health record. As defined by prior studies,14, 19 patients with documented HR of >95 beats/min for >12 hours in any 24-hour period were categorized into the prolonged elevated heart rate (PEHR) group. Delayed cerebral ischemia from cerebral vasospasm (DCI) was defined as (1) clinical deterioration (i.e. a new focal deficit, decrease in level of consciousness, or both), and/or (2) a new infarct on CT that was not visible on the admission or immediate postoperative scan, when the cause was thought by the research team to be vasospasm.19 Major adverse cardiopulmonary events and their date of onset were prospectively adjudicated in weekly meetings of the clinical team. Pulmonary edema was defined as radiographic evidence of perihilar infiltrates and an increased arterial-alveolar gradient with appropriate clinical signs and symptoms. Hypotension was defined as SBP <90 mm Hg treated with vasopressors. Myocardial injury was defined as an abnormal troponin elevation (>0.4 lg/l). Cardiac arrest was defined as spontaneous pulselessness due to failure of the heart to contract effectively, excluding cases where the arrest comes as a consequence of withdrawal of care.

Outcome Assessment

Global outcome at 3-months was assessed with a 7-point version of the modified Rankin Scale (mRS) rated from death (6) to symptom-free full recovery (0). 20 Poor outcome was defined as death or moderate-to-severe disability (unable to walk or tend to bodily needs, mRS score 4 to 6).

Statistical Analysis

Data analyses were performed with R statistical software (R, version 2.12.2, R Project). P ≤ 0.05 were considered significant. Logistic regression was used to identify admission predictors of PEHR using candidate variables with univariate associations P<0.25. Tests for interactions were performed for all significant variables retained in baseline multifactorial models. Survival rates of PEHR calculated using the Kaplan-Meier method were expressed as a percentage surviving 50 days. The log rank test was used to test the difference between survival curves. Cox regression was used to calculate hazard ratios and 95% confidence intervals for risk factors. Time-dependent covariates were used to assess the temporal relationship of PEHR to specific cardiopulmonary complications. Logistic regression was used to test the relationship of PEHR to 3-month outcome using known predictors of poor outcome 18 as covariates. In accordance with PCORI methodological guidelines 21 we performed multiple imputation using Bayesian methods 22 to account for 3-month modified Rankin Scores lost to follow-up. Procedures to create and analyze five imputed datasets were carried out using the ‘mi’ package 23 for R. Diagnostic plots were used to evaluate the fit of the imputed values produced by the marginal model.

Results

Study Population

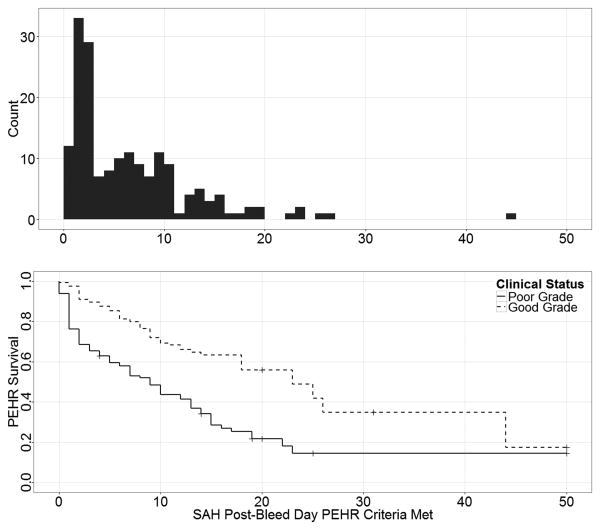

Overall 39% (N=175) of patients experienced PEHR during their hospitalization. Patients with PEHR were more likely to be nonwhite but otherwise had similar demographics and past medical histories (Table 1). PEHR patients had significantly longer and more complicated ICU stays, requiring more mechanical ventilation and continuous sedation (Table 2). The onset of PEHR occurred within 72 hours of SAH in 42% (N=74) of affected patients (Figure 1). A secondary peak of PEHR onset between SAH day 3 and 10 occurred in 36% (N=63) of patients.

Table 1. Baseline Predictors of Prolonged Elevated Heart Rate.

| Characteristics | Prolonged Elevated HR N=175 | Control Group N=272 | OR (95% CI) | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | ||||

| Age, years | 55 (16) | 56 (14) | 0.97 (0.9, 1.03)* | 0.3 |

| Female | 119 (68%) | 179 (66%) | 1.1 (0.7, 1.7) | 0.6 |

| Non white | 127 (73%) | 151 (56%) | 2.1 (1.4, 3.2) | < 0.001 |

| Beta-blocker usage | 17 (10%) | 47 (17%) | 0.5 (0.3, 0.9) | 0.027 |

| Other antihyperintensive agents | 47 (27%) | 70 (26%) | 0.9 (0.6, 1.5) | 0.8 |

| Symptoms at Onset | ||||

| Loss of consciousness | 100 (57%) | 90 (33%) | 2.7 (1.8, 4.0) | < 0.001 |

| Seizures | 35 (20%) | 17 (6%) | 3.7 (2.0, 6.9) | < 0.001 |

| Cardiac Arrest requiring CPR | 16 (9%) | 5 (2%) | 5.4 (1.9, 15) | < 0.001 |

| Admission Clinical Grade | ||||

| Hunt, Hess Grade | ||||

| I Mild headache | 10 (6%) | 71 (26%) | 1.0 | < 0.001 |

| II Severe headache | 29 (17%) | 80 (29%) | 2.6 (1.2, 5.7) | |

| III Lethargic or confused | 40 (23%) | 55 (20%) | 5.2 (2.4, 11) | |

| IV Stupor | 42 (24%) | 22 (8%) | 14 (5.9, 31) | |

| V Coma | 54 (31%) | 44 (16%) | 8.7 (4.0, 19) | |

| Admission GCS | ||||

| 15, alert | 31 (18%) | 143 (53%) | 1.0 | < 0.001 |

| 9 – 14, lethargic or stuporous | 55 (32%) | 44 (16%) | 5.8 (3.3, 10) | |

| 3 – 8, comatose | 86 (50%) | 82 (30%) | 4.8 (3.0, 8) | |

| APACHE-2 physiological | 8 (6, 12) | 6 (5, 9) | 1.1 (1.1, 1.2) | < 0.001 |

| Admission Echocardiogram | ||||

| Reduced ejection fraction | 39 (25%) | 27 (13%) | 2.2 (1.3, 3.8) | 0.004 |

| Wall motion abnormalities | ||||

| Any | 31 (18%) | 25 (9%) | 2.1 (1.1, 4.7) | 0.009 |

| Inferior | 20 (13%) | 13 (6%) | 2.2 (1.2, 3.7) | 0.03 |

| Anterior | 20 (13%) | 9 (4%) | 3.3 (1.5, 7.5) | 0.004 |

| Septum | 26 (17%) | 13 (6%) | 3.0 (1.5, 6.1) | 0.002 |

| Lateral | 14 (9%) | 13 (6%) | 1.5 (0.7, 3.3) | 0.3 |

| Posterior | 14 (9%) | 7 (3%) | 2.8 (1.1, 7.2) | 0.03 |

| Apex | 13 (9%) | 11 (6%) | 1.6 (0.7, 3.7) | 0.25 |

| Admission CT | ||||

| SAH sum score ≥15† | 111 (66%) | 129 (50%) | 2.0 (1.3, 3.0) | < 0.001 |

| IVH present | 121 (73%) | 141 (54%) | 2.3 (1.5, 3.5) | < 0.001 |

| ICH present | 39 (23%) | 33 (12%) | 2.1 (1.3, 3.6) | 0.003 |

| Modified Fisher Score | ||||

| 0 or 1, no or thin SAH | 27 (16%) | 91 (33%) | < 0.001 | |

| 2, thin SAH, bilateral IVH | 20 (12%) | 21 (8%) | 3.2 (1.5, 6.8) | |

| 3, thick SAH | 69 (40%) | 96 (35%) | 2.4 (1.4, 4.1) | |

| 4, thick SAH, bilateral IVH | 56 (33%) | 64 (24%) | 3.0 (1.7, 5.2) | |

| Cerebral edema | 110 (66%) | 111 (42%) | 2.7 (1.8, 4.0) | < 0.001 |

| Bicaudate Index ≥16 | 63 (40%) | 63 (26%) | 1.9 (1.3, 2.9) | 0.003 |

| Aneurysm Characteristics | ||||

| Size >10 mm | 21 (12%) | 30 (11%) | 1.1 (0.6, 2.0) | 0.8 |

| Posterior circulation | 21 (13%) | 39 (16%) | 0.8 (0.4, 1.3) | 0.3 |

OR per 5 years of age;

Scaled 0=no blood, 30=all cisterns and fissures completely filled with blood

Values are N (%), mean (SD), or median (25%, 75%)

Table 2. Treatment During Intensive Care Unit (ICU) Stay.

| Characteristics | Prolonged Elevated HR N=175 |

Control Group N=272 |

OR (95% CI) | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ICU stay, days | 15.2 [8.6] | 9.9 [23] | 1.05 (1.03, 1.08) | < 0.001 |

| Surgical Clipping | 105 (61%) | 129 (48%) | 1.7 (1.1, 2.5) | 0.009 |

| Endovascular Coiling | 41 (24%) | 60 (23%) | 1.1 (0.7, 1.7) | 0.71 |

| Mechanical ventilation | 133 (76%) | 85 (31%) | 7.0 (4.5, 11) | < 0.001 |

| Insulin Drip | 150 (86%) | 182 (67%) | 3.0 (1.8, 4.9) | < 0.001 |

| Cooling | 93 (53%) | 32 (12%) | 8.5 (5.3, 14) | < 0.001 |

| Vasopressor support | 143 (82%) | 107 (39%) | 6.9 (4.4, 10) | < 0.001 |

| Beta-blocker | 61 (35%) | 54 (20%) | 2.2 (1.4, 3.3) | < 0.001 |

| Nicardipine | 142 (77%) | 224 (73%) | 1.2 (0.8, 1.9) | 0.38 |

| Mannitol | 83 (47%) | 59 (22%) | 3.2 (2.1, 4.9) | < 0.001 |

| HHT therapy | 77 (44%) | 38 (14%) | 4.9 (3.1, 7.7) | < 0.001 |

Values are N (%) or mean [SD]

Figure 1.

The top panel depicts the SAH day that patients met criteria for PEHR. The bottom panel shows PEHR survival by admission clinical grade (Hunt-Hess Grade ≥ 4). A multifactorial Cox regression model revealed that the hazard for PEHR was significantly associated with nonwhite race/ethnicity (HR 1.5, 95% CI 1.04, 2.1, P=0.027), documented pre-hospital beta-blocker use (HR 0.63, 95% CI 0.45, 0.88, P=0.007), admission Hunt-Hess Grade (HR 2.1, 95% CI 1.5, 2.9, P<0.001), ICU beta-blocker administration (HR 1.5, 95% CI 1.07, 2.1, P=0.019), hypotension during ICU stay (HR 1.7, 95% CI 1.2, 2.4, P=0.001), fever (HR 1.5, 95% CI 1.05, 2.06, P=0.024), and infarction from cerebral vasospasm (HR 1.7, 95% CI 1.1, 2.6, P=0.009).

Predictors of PEHR

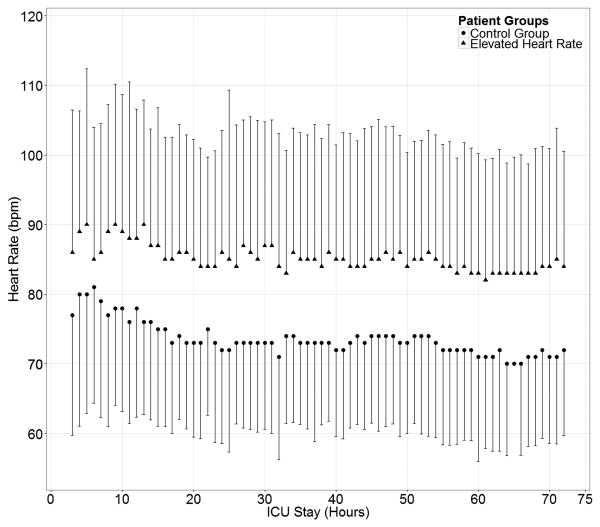

PEHR patients had a significantly higher mean heart rate (86±18 bpm) during the first 72 hours after SAH compared to non-PEHR patients (74±14 bpm, P<0.001; Figure 2). Multifactorial logistic regression revealed that nonwhite race/ethnicity (OR 3.1, 95% CI 1.9-4.9, P<0.001), admission Hunt-Hess grade ≥ 4 (OR 2.9, 95% CI 1.8-4.9, P<0.001), elevated admission APACHE-2 physiological subscore (OR 1.07, 95% CI 1.02-1.1, P=0.012), and modified Fisher score (OR 1.3, 95% CI 1.07-1.6, P=0.008) were associated with an increased risk of PEHR, whereas documented pre-hospital beta-blocker use (OR 0.3, 95% CI 0.2-0.7, P=0.002) was protective. Aneurysm clipping procedure was also significantly associated with PEHR when added to this model (OR 2.4 95% CI 1.5-3.8, P<0.001).

Figure 2.

Heart rate of PEHR patients compared to non-PEHR patients in the first 72 hours after admission.

Delayed Cerebral Ischemia from Cerebral Vasospasm

PEHR was associated with an increased risk of delayed cerebral ischemia (DCI) from cerebral vasospasm (Table 3). Of the 56 PEHR patients that developed DCI, 18 (32%) had early PEHR (< 72 hours after SAH onset) and 38 (68%) had late-onset PEHR (≥ 72 hours after SAH onset). Multifactorial logistic regression revealed that after controlling for Hunt and Hess grade (OR 0.4, 95% CI 0.23 to 0.71, P=0.002) and inotropic support (OR 63, 95% CI 14 to 265, P<0.001), DCI was associated with late-onset PEHR (OR 2.6, 95% CI 1.4 to 4.9, P=0.003) but not early-onset PEHR (OR 1.5, 95% CI 0.7 to 3.0, P=0.3). A Cox regression model using time-lagged covariates was generated to evaluate the precise timing the PEHR onset to DCI onset. The risk of DCI was more than twofold in patients having PEHR onset in previous 2 days (HR 2.4, 95% CI 1.2 to 4.9, P=0.011) after controlling for Hunt and Hess Grade (HR 1.6, 95% CI 0.7 to 3.5, P=0.2), inotropic support (HR 14.1, 95% CI 7.7 to 25, P<0.001), and their two-way interaction (HR 0.22, 95% CI 0.8 to 0.57, P=0.002). The risk of DCI was not significantly associated with PEHR occurrence on or in the days following DCI onset.

Table 3. Frequency of Complications.

| Characteristics | Prolonged Elevated HR N=175 |

Control Group N=272 |

OR (95% CI) | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Neurological | ||||

| Rebleed | 18 (11%) | 19 (6%) | 2.1 (1.1-4.1) | 0.03 |

| Herniation | 28 (18%) | 35 (11%) | 1.8 (1-3.1) | 0.04 |

| DCI from cerebral vasospasm | 56 (32%) | 30 (11%) | 3.8 (2.3-6.2) | < 0.001 |

| Medical | ||||

| Fever > 101.5°F | 92 (58%) | 113 (34%) | 2.6 (1.8-3.9) | < 0.001 |

| Pneumonia | 53 (33%) | 55 (17%) | 2.5 (1.6-3.8) | < 0.001 |

| Sepsis | 20 (12%) | 17 (5%) | 2.6 (1.3-5.2) | 0.005 |

| Cardiac | ||||

| Arrhythmias | 33 (19%) | 38 (14%) | 1.4 (0.9, 2.4) | 0.16 |

| Cardiac Arrest (in ICU) | 3 (2%) | 7 (3%) | 0.7 (0.2, 2.6) | 0.55 |

| Myocardial Infarction | 29 (17%) | 14 (5%) | 3.7 (1.9, 7.2) | < 0.001 |

| Pulmonary Edema | 61 (35%) | 25 (9%) | 5.3 (3.2, 9.0) | < 0.001 |

| Hypertension | 138 (79%) | 194 (71%) | 1.5 (0.96, 2.4) | 0.08 |

| Hypotension SBP < 90 mm Hg | 80 (46%) | 58 (21%) | 3.1 (2.0, 4.7) | < 0.001 |

Values are N (%), DCI = Delayed Cerebral Ischemia

Cardiopulmonary Complications

PEHR was associated with an increased risk of hypertension, hypotension, pulmonary edema, myocardial injury, but not with arrhythmia or in-hospital cardiac arrest (Table 3). Significantly more PEHR patients sustained myocardial injury (17% overall, mean peak troponin I level 4.4 ± 4.5 ng/dl) compared to non-PEHR patients (5%, mean peak troponin I level 1.7 ± 1.6 ng/dl). The majority of myocardial injury events (81%) occurred within 48 hours of admission. Of the remaining twelve myocardial injury events that occurred after 48 hours, ten were in the PEHR group and eight of these met criteria for PEHR an average of 23 hours before myocardial injury was documented. In order to evaluate the timing of PEHR in relation to these cardiopulmonary complications Cox regression models using time-lagged covariates were generated (Table 4). PEHR occurred more frequently over the two days preceding myocardial injury and pulmonary edema onset, and on the day of pulmonary edema and hypotension onset, compared to patients who did not develop these complications. These relationships were maintained even after censoring time periods when catecholamine support was administered.

Table 4. Relationship of Timing of PEHR to Major Adverse Cardiopulmonary Events.

| Myocardial Injury | Pulmonary Edema | Hypotension | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristics | Adjusted HR (95% CI) |

P | Adjusted HR (95% CI) |

P | Adjusted HR (95% CI) |

P |

| Hunt-Hess Grade | 2.4 (1.1 to 5.1) | 0.023 | 2.1 (1.8 to 2.6) | <0.001 | 3.9 (3.0 to 5.2) | <0.001 |

| PEHR | ||||||

| Previous 48 hours | 3.5 (1.2 to 11) | 0.024 | 1.6 (1.3 to 2.0) | <0.001 | ||

| Same day | 1.7 (1.3 to 2.3) | <0.001 | 1.5 (1.0 to 2.3) | 0.04 | ||

| Following 48 hours | 1.6 (1.3 to 2.0) | <0.001 | ||||

Multifactorial Cox regression models using time-lagged covariates were created to evaluate the timing of PEHR in relation to the calendar day of onset of myocardial injury (troponin elevation), pulmonary edema (characteristic clinical and radiographic findings with documented hypoxia), and hypotension (SBP <90 mm Hg treated with pressors), controlling for admission Hunt-Hess grade. Inotropic support in the previous 48 hours did not significantly increase the hazard of these complications.

Three-Month Outcome

We imputed 3-month modified Rankin scores for 19% (N=85) of patients that were lost to follow-up. We found that 56% of PEHR patients were dead or severely disabled at 3 months (mRS 4-6) compared to 26% of those without PEHR (OR 3.7, 95% CI 3.3, 4.2). In a multifactorial logistic regression model PEHR was a significant predictor of 3-month morbidity and mortality after adjusting for age, admission Hunt-Hess grade, aneurysm Size ≥ 10 mm, APACHE-2 physiological subscore, pulmonary edema, infarction from cerebral vasospasm, fever, pneumonia, and congestive heart failure (Table 5). Excluding patients requiring CPR at SAH onset or ICU time periods when patients were given catecholamines for treatment of hypotension or delayed cerebral ischemia from vasospasm did not eliminate the significant relationship between PEHR to poor outcome.

Table 5. Multivariable Logistic Regression for Three-Month Modified Rankin.

| Characteristics | OR (95% CI) | P |

|---|---|---|

| Age | 1.08 (1.05, 1.1) | < 0.001 |

| Admission Hunt and Hess Grade ≥ 4 | 9.6 (4.7, 19) | < 0.001 |

| Aneurysm Size ≥ 10 mm | 4.2 (1.5, 11) | 0.004 |

| APACHE-2, Physiology | 1.2 (1.1, 1.3) | 0.001 |

| Pulmonary Edema | 2.6 (1.1, 6) | 0.035 |

| Infarction from Cerebral Vasospasm | 3.4 (1.0,11) | 0.04 |

| Fever | 0.6 (0.3, 1.3) | 0.20 |

| Pneumonia | 1.8 (0.9, 4) | 0.11 |

| Congestive Heart Failure | 0.4 (0.1, 1.6) | 0.18 |

| Prolonged Elevated Heart Rate | 3.7 (3.3, 4.2) | 0.019 |

Discussion

In this study of 447 SAH patients we found that approximately 40% of patients experienced PEHR at some point during their ICU stay. PEHR was associated with poor clinical grade and physiologic dysfunction assessed with APACHE-2 scores, and the risk was reduced in patients with pre-admission beta-blocker use. Late-onset PEHR was significantly associated with, and preceded the development of, DCI from vasospasm. PEHR was highly associated with adverse cardiopulmonary events, including hypertension and hypotension requiring vasoactive therapy, pulmonary edema, and myocardial injury evidenced by troponin elevation. PEHR was also associated with poor 3-month outcome after adjustment for established prognostic factors.

Our primary hypothesis was confirmed in that PEHR was significantly associated with an increased risk of major cardiopulmonary events and poor outcome. Catecholamine-mediated cardiac injury 10 and pulmonary edema 8 during the acute phase of SAH is well described, but an unanswered question is whether SAH patients remain vulnerable to sympathetically-mediated myocardial injury over time. PEHR had a biphasic distribution of onset in our study, with approximately 40% of initial episodes occurring within 72 hours of SAH onset and 40% occurring in delayed fashion between SAH days 3 and 10. Studies in high-risk critically ill patients 14 and post-operative patients 24 have reported that heart rate elevations occur in 90% or more of patients before adverse cardiac events occur. Our results from time-lagged Cox regression analyses suggest that PEHR tended to precede the onset of myocardial injury (troponin elevation) and pulmonary edema, and occur on the same day as pulmonary edema and hypotension. These relationships were maintained even after censoring time periods when catecholamine support was administered, suggesting that these relationships cannot be fully explained by use of adrenergic agents in sicker patients.

The precise mechanism and causal pathways of how PEHR relates to myocardial injury and poor outcome remain difficult to unravel. SAH is unique in that the primary bleeding event triggers a powerful neurogenic catecholamine surge. The inflammatory response observed after SAH often results in elevated heart rate and systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS), which has been shown to be associated with the development of delayed cerebral ischemia. 25 There are myriad other causes of sinus tachycardia in critically-ill patients, however, including but not limited to pain, agitation, hypovolemia, infection, fever and systemic inflammation, or vasoactive therapy with vasodilators or vasopressors. In critically-ill patients multiple potential causes may coexist, making it difficult or impossible to pinpoint a precise cause. The risk of DCI onset was associated only with preceding PEHR onset making it less likely that late-onset PEHR was a side effect of treatment interventions for DCI. We suspect that early PEHR (<72 hours after SAH onset) is primarily driven by neurogenic sympathetic hyperactivity, whereas non-neurogenic causes (i.e. systemic inflammation, pain, infection) may contribute to many late-onset cases.

The sympathetic surge that occurs with SAH can directly cause myocardial injury during the acute phase of SAH, 6 both by precipitating demand ischemia when coronary perfusion demand exceeds supply, and by inducing myocardial contraction band necrosis. We hypothesize that PEHR is a readily identifiable and treatable biomarker of this catecholamine surge and systemic inflammation, reflecting both direct beta-1 receptor stimulation and the compensatory response of a weakened left ventricle. Our results show that PEHR is mitigated by pre-admission beta blocker use and is associated with poor outcome even after controlling for established predictors. This suggests that PEHR may be a modifiable pathological process that directly contributes to poor outcome, rather than a non-specific marker of injury severity.

Beta-blockade has been associated with improved outcomes after SAH 26,27 and traumatic brain injury, 28 perhaps by reducing adrenergic feedback to the central nervous system. 27 Coghlan et al. 29 recently called for a reevaluation of therapeutic options to reduce heart rate in SAH patients after finding a relationship between tachycardia and poor outcome in the Intraoperative Hypothermia Aneurysm Surgery Trial. Multicenter registry data suggests that a large proportion of patients receive agents for blood pressure control that preferentially reduce afterload, such as nicardipine, hydralazine, and sodium nitroprusside, during the acute phase of SAH. 30 The clinical relevance of PEHR can be established by prospective intervention studies specifically designed to evaluate early sympatholytic therapy directed at heart rate control as a strategy to reduce complications and improve outcome after SAH.

Our study is limited by its observational design and is potentially confounded by the use of catecholaminergic agents that might have caused PEHR, despite methodological and statistical attempts to address this concern. We have no data on the relative importance of the many different causes of PEHR in our subjects. Future studies would benefit by including direct measurements of catecholamine levels and inflammatory markers related to sympathetic activation 31 in order to help elucidate mechanistic pathways related to PEHR. Studies may also benefit from measuring autonomic nervous system (ANS) integrity by using provocative maneuvers that evaluate heart rate variability changes to deep breathing, valsalva maneuvers, cold stimulation and norepinephrine challenge tests. 32

Conclusions

PEHR is common after SAH, associated with poor outcome, and may contribute to the development of myocardial injury and other serious cardiopulmonary complications. Studies evaluating the routine use of sympatholytic therapy using titratable beta-blocking agents to minimize myocardial demand and catecholamine-mediated injury during the acute phase of SAH are justified.

Acknowledgments

Sources of Funding: The project described was supported in part by a research grant from Baxter Healthcare™. The sponsors had no involvement in the collection, analysis, and interpretation of data; in the writing of the report; or in the decision to submit the paper for publication. Additional support was provided by the Charles A. Dana Foundation (SAM) and by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, National Institutes of Health, through Grant Number KL2 TR000081, formerly the National Center for Research Resources, Grant Number KL2 RR024157 (JMS). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH.

References

- 1.Cruickshank J, Neil-Dwyer G, Stott A. Possible role of catecholamines, corticosteroids, and potassium in production of electrocardiographic abnormalities associated with subarachnoid haemorrhage. British heart journal. 1974;36:697. doi: 10.1136/hrt.36.7.697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dilraj A, Botha JH, Rambiritch V, Miller R, van Dellen JR. Levels of catecholamine in plasma and cerebrospinal fluid in aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage. Neurosurgery. 1992;31:42. doi: 10.1227/00006123-199207000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Grad A, Kiauta T, Osredkar J. Effect of elevated plasma norepinephrine on electrocardiographic changes in subarachnoid hemorrhage. Stroke. 1991;22:746–9. doi: 10.1161/01.str.22.6.746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Naredi S, Lambert G, Eden E, et al. Increased sympathetic nervous activity in patients with nontraumatic subarachnoid hemorrhage. Stroke. 2000;31:901–6. doi: 10.1161/01.str.31.4.901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cruickshank J, Neil-Dwyer G, Lane J. The effect of oral propranolol upon the ECG changes occurring in subarachnoid haemorrhage. Cardiovascular research. 1975;9:236–45. doi: 10.1093/cvr/9.2.236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Naidech AM, Kreiter KT, Janjua N, et al. Cardiac troponin elevation, cardiovascular morbidity, and outcome after subarachnoid hemorrhage. Circulation. 2005;112:2851. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.533620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Temes RE, Schmidt JM, Naidech AM, et al. Association of Severe Left Ventricular Dysfunction After SAH with Stroke from Delayed Vasospasm and Functional Outcome Among Patients. 3rd Annual Meeting of the Neurocritical Care Society (Platform Presentation), Neurocrit Care; Pheonix, AZ. 2005. p. 2. 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Muroi C, Keller M, Pangalu A, Fortunati M, Yonekawa Y, Keller E. Neurogenic pulmonary edema in patients with subarachnoid hemorrhage. Journal of neurosurgical anesthesiology. 2008;20:188–92. doi: 10.1097/ANA.0b013e3181778156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Frontera JA, Parra A, Shimbo D, et al. Cardiac Arrhythmias after Subarachnoid Hemorrhage: Risk Factors and Impact on Outcome. Cerebrovasc Dis. 2008;26:71–8. doi: 10.1159/000135711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Banki NM, Kopelnik A, Dae MW, et al. Acute neurocardiogenic injury after subarachnoid hemorrhage. Circulation. 2005;112:3314–9. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.558239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brouwers PJ, Westenberg H, Van Gijn J. Noradrenaline concentrations and electrocardiographic abnormalities after aneurysmal subarachnoid haemorrhage. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery & Psychiatry. 1995;58:614–7. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.58.5.614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Crago E, Kerr M, Kong Y, et al. The impact of cardiac complications on outcome in the SAH population. Acta neurologica scandinavica. 2004;110:248–53. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0404.2004.00311.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mayer S, Fink M, Homma S, et al. Cardiac injury associated with neurogenic pulmonary edema following subarachnoid hemorrhage. Neurology. 1994;44:815. doi: 10.1212/wnl.44.5.815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sander O, Welters ID, Foëx P, Sear JW. Impact of prolonged elevated heart rate on incidence of major cardiac events in critically ill patients with a high risk of cardiac complications*. Critical Care Medicine. 2005;33:81. doi: 10.1097/01.ccm.0000150028.64264.14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Auerbach AD, Goldman L. β-Blockers and reduction of cardiac events in noncardiac surgery. JAMA: The Journal of the American Medical Association. 2002;287:1435–44. doi: 10.1001/jama.287.11.1435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bederson JB, Connolly ES, Batjer HH, et al. Guidelines for the management of aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage. Stroke. 2009;40:994–1025. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.108.191395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Komotar R, Schmidt J, Starke R, et al. Resuscitation and critical care of poor-grade subarachnoid hemorrhage. Neurosurgery. 2009;64:397. doi: 10.1227/01.NEU.0000338946.42939.C7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wartenberg KE, Schmidt JM, Temes RE, et al. Medical complications after subarachnoid hemorrhage: Frequency and impact on outcome. Stroke. 2005;36:521. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Claassen J, Bernardini GL, Kreiter K, et al. Effect of cisternal and ventricular blood on risk of delayed cerebral ischemia after subarachnoid hemorrhage: the Fisher scale revisited. Stroke. 2001;32:2012–20. doi: 10.1161/hs0901.095677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.de Haan R, Limburg M, Bossuyt P, van der Meulen J, Aaronson N. The clinical meaning of Rankin ‘handicap’ grades after stroke. Stroke. 1995;26:2027–30. doi: 10.1161/01.str.26.11.2027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Scharfstein S, Neaton J, Hogan J, et al. Minimal Standards in the Prevention and Handling of Missing Data in Observational and Experimental Patient Centered Outcomes Research. 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rubin DB. Multiple Imputation for Nonresponse in Surveys. New York: Wiley; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Su YS, Gelman A, Hill J, Yajima M. Multiple imputation with diagnostics (mi) in R: Opening windows into the black box. Journal of Statistical Software. 2011;45:1–31. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Landesberg G, Luria M, Cotev S, et al. Importance of long-duration postoperative ST-segment depression in cardiac morbidity after vascular surgery. The Lancet. 1993;341:715–9. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(93)90486-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dhar R, Diringer MN. The Burden of the Systemic Inflammatory Response Predicts Vasospasm and Outcome after Subarachnoid Hemorrhage. Neurocrit Care. 2008 doi: 10.1007/s12028-008-9054-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Neil-Dwyer G, Walter P, Cruickshank J, Stratton C. Beta-blockade in subarachnoid haemorrhage. Drugs (Suppl 2) 1983;25:273–7. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Neil-Dwyer G, Walter P, Cruickshank J. β-blockade benefits patients following a subarachnoid haemorrhage. European journal of clinical pharmacology. 1985;28:25–9. doi: 10.1007/BF00543706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cotton BA, Snodgrass KB, Fleming SB, et al. Beta-blocker exposure is associated with improved survival after severe traumatic brain injury. The Journal of Trauma and Acute Care Surgery. 2007;62:26–35. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e31802d02d0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Coghlan LA, Hindman BJ, Bayman EO, et al. Independent associations between electrocardiographic abnormalities and outcomes in patients with aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage findings from the intraoperative hypothermia aneurysm surgery trial. Stroke. 2009;40:412–8. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.108.528778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mayer SA, Kurtz P, Wyman A, et al. Clinical practices, complications, and mortality in neurological patients with acute severe hypertension: the Studying the Treatment of Acute hyperTension registry. Crit Care Med. 2011;39:2330–6. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3182227238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Naredi S, Lambert G, Friberg P, et al. Sympathetic activation and inflammatory response in patients with subarachnoid haemorrhage. Intensive Care Medicine. 2006;32:1955–61. doi: 10.1007/s00134-006-0408-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schmidt HB, Werdan K, Müller-Werdan U. Autonomic dysfunction in the ICU patient. Current opinion in critical care. 2001;7:314–22. doi: 10.1097/00075198-200110000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]