Abstract

Dietary management for phenylketonuria was established over half a century ago, and has rendered an immense success in the prevention of the severe mental retardation associated with the accumulation of phenylalanine. However, the strict low-phenylalanine diet has several shortcomings, not the least of which is the burden it imposes on the patients and their families consequently frequent dietary non-compliance. Imperfect neurological outcome of patients in comparison to non-PKU individuals and nutritional deficiencies associated to the PKU diet are other important reasons to seek alternative therapies. In the last decade there has been an impressive effort in the investigation of other ways to treat PKU that might improve the outcome and quality of life of these patients. These studies have lead to the commercialization of sapropterin dihydrochloride, but there are still many questions regarding which patients to challenge with sapropterin what is the best challenge protocol and what could be the implications of this treatment in the long-term. Current human trials of PEGylated phenylalanine ammonia lyase are underway, which might render an alternative to diet for those patients non-responsive to sapropterin dihydrochloride. Preclinical investigation of gene and cell therapies for PKU is ongoing. In this manuscript, we will review the current knowledge on novel pharmacologic approaches to the treatment of phenylketonuria.

Keywords: Phenylketonuria, Tetrahydrobiopterin, Sapropterin, Phenylalanine ammonia lyase, Gene therapy

1. Introduction

Phenylketonuria (PKU; OMIM 2626000) is one of the most common inborn errors of metabolism. It is a recessively inherited disease caused by mutations in the gene encoding the enzyme phenylalanine hydroxylase (PAH; EC 1.14.16.1) [1]. It is also the first metabolic disorder in which a toxic agent, phenylalanine (Phe), was identified to cause mental retardation, and in which treatment was found to prevent clinical symptoms. The dietary management of PKU was established 60 years ago [2], with the first effects of treatment published in 1953 [3]. The PKU diet consists in a restriction of dietary natural protein in order to minimize Phe intake. It requires supplementation with special medical formulas that supply sufficient essential aminoacids, energy, vitamins and minerals. To avoid mental retardation, the diet should be started in the first weeks of age; therefore, neonatal screening programs are essential in the early identification of these patients. Treatment should be maintained for life, as hyperphenylalaninemia in adulthood has been associated with attention problems, mood instability and white matter degeneration leading to seizures and gait disturbances [4,5]. During pregnancy, moderately high Phe levels in the mother can cause microcephaly, mental retardation and congenital heart defects in the fetus [6].

Dietary treatment has been very effective in preventing severe mental retardation, but it has several shortcomings [5,7]. Even though medical formulas have improved in nutritional quality and palatability over the years, the severely restrictive diet necessary for the treatment of PKU still carries risk of associated nutritional deficiencies. There have been reports of growth retardation and specific deficits such as calcium, iron, selenium, zinc or vitamin D and B12 deficiencies [8–10]. Signs of osteoporosis may develop at an early age [11]. Besides nutritional considerations, the PKU diet imposes a heavy burden, both economical and social, upon the patient and their families [12]. It is therefore not surprising that non-compliance, particularly among adolescents and adults, is common [13,14]. Most disturbingly, it is evident that even early and continuously treated PKU patients may not attain their full neurodevelopmental potential. Treated PKU patients typically exhibit normal intellectual quotients (IQ), but there is, still an IQ gap when compared to their non-PKU siblings or classmates [5,15,16]. Treated PKU patients frequently show delays in certain neurological functions , which likely contribute to poor results in school and long-term employment [17]. Executive function seems to be the most consistently affected area in PKU patients [18–20]. Anxiety, depression and a low self esteem have also been reported [21].

For all these reasons, novel alternative therapies for PKU have been sought. Due to the strong link between neurological outcome and blood Phe levels, most new treatment approaches will try aim to decrease blood Phe levels. However, clinical objectives are no longer centered exclusively on blood Phe levels, but also on the impact of blood Phe upon brain aminoacid concentrations, early neurodevelopment and long-term neurologic outcome. Attaining normal growth and body mass, and avoiding nutritional deficiencies are other important factors in the consideration of outcome. Finally, the patient's psychosocial well-being has become a key point in PKU treatment objectives, as other approaches lead to non-compliance and eventually important clinical manifestations.

New dietary therapies include more palatable medical formulas, large neutral aminoacids supplementation [22] and the development of medical foods based upon glycomacropeptide, a naturally low-Phe protein [23]. The increasing knowledge of the genetic basis of disease and enzymology has allowed for the investigation of novel pharmacologic therapies to directly ameliorate the effects of a mutant enzyme. For example, pharmacologic chaperones, including the naturally occurring cofactor. 5,6,7,8-tetrahydrobiopterin (BH4), help stabilize misfolded mutant enzymes and prevent proteolisis. BH4 the cofactor of PAH, has been used to treat a subset of PKU patients for almost a decade under experimental conditions. In the past 2–3 years, BH4 has begun to be commercialized in the form of sapropterin dihydrochloride, a synthetic form of BH4, and is beginning to be widely available. Orthotopic liver transplantation succesfully cured PKU in a single patient who was transplanted because of cryptogenetic cirrhosis [1]. Therapeutic liver repopulation following hepatocyte transplant continues to be investigated in preclinical models [24]. Clinical gene therapy trials are underway in several inborn errors of metabolism, and preclinical gene transfer experiments continue in PKU animal models. Finally , a novel enzyme substitution approach that utilizes subcutaneous injection of phenylalanine ammonia lyase to metabolize circulating blood Phe, is currently in clinical trial. This paper aims to summarize and review the current knowledge on the pharmacological approach to the treatment of PKU.

2. Tetrahydrobiopterin (BH4)

Tetrahydrobiopterin is the natural cofactor of the PAH enzyme. The lack of BH4 gives rise not only to disfunction of PAH (and therefore hyperphenylalaninemia), but also to disfunction of brain tyrosine and tryptophan hydroxylases, leading to the very severe neurologic manifestations neurotrasmitter deficiencies in the different BH4 deficient syndromes [25]. In the 1980s, colleagues began to employ oral BH4 challenges to detect neonates with inherited BH4 deficiencies [26]. Unfortunately, these short-term challenge protocols did not typically detect individuals with of BH4-responsive PAH deficiency, which requires test protocols of longer duration and higher BH4 doses [25]. It was not until 1999 that Kure et al. first showed that in some patients with mutations in the PAH gene pharmacological doses of BH4 (20 mg/kg) could reduce blood Phe levels [27]. Since then, 10 to 60% of patients with a deficiency of the PAH enzyme have been found to be BH4-responsive, depending on the mutations prevalent in the different populations [28–36]. Initially, only some centers had access to a non-commercial form of BH4 (Shircks Laboratories, Jona, Switzerland), but since then, sapropterin dihydrocloride was developed and commercially launched after regulatory approval in the US in 2007 and in a growing number of countries in Europe and worldwide since 2008.

Not all PAH-deficient patients respond to BH4 and among those who do, there is a wide range in the extent of the response. In order to assess whether a PAH-deficient patient is responsive to BH4, an oral challange is employed. Different protocols have been developed. In general, European centers favor shorter tests, similar to that proposed by Blau et al. [37]. This test consists of blood Phe monitoring at 0, 8, 16 and 24 h during 2 consecutive days, while receiving a 20 mg/kg/day. It is recommended that basal Phe levels be>400 μmol/L and that blood Phe levels are closely monitored during the previous days in order to avoid false negative or positive results. A decrease of the blood Phe levels with respect to the basal value of at least 30% is considered a positive response. A negative result would be a reduction of less than 20%, while if the reduction is between 20% and 30% a longer response protocol (1 to 3 weeks), with daily blood Phe concentration measurements, is recommended to establish BH4 responsiveness. In the USA, longer-term challenges are the common. In the protocol proposed by Levy et al., 20 mg/kg of BH4 is given daily for 2 to 4 weeks, with blood Phe samples taken weekly [38]. Cutoff Phe levels are similar to European standards, considering positive a reduction of more than 30%. These are general recommendations that unite the most common trends followed in the different centers, but different goals can be set for individual patients. In general, 48-hour tests detect most BH4-responders if multiple blood Phe measurements are taken. Short-term challange protocols allow treatment decisions to be made sooner, at a lower cost and with less interference of possible dietary interventions or infectious episodes. On the other hand, longer tests are less likely to miss possible late-responders [39] and can be used to assess other benefits of the treatment such as effects upon neurocognitive function.

Although not generally available, different methods of detecting a response to BH4 exist. The 13C-Phe oxidation test may be a useful and safe diagnostic tool to assess the effect of BH4 on in vivo enzyme activity in the individual patient. In this test, the percentage of expired 13CO2 recovered after an oral ingestion of BH4 rises significantly in responsive patients indicating that BH4 improves in vivo PAH enzyme activity [29,40].

In general, patients with milder phenotypes have a higher response rate to BH4 than those with low Phe tolerance [29–36]. A mutation database (BIOPKU database), which includes all mutations reported to respond to BH4, is available (www.biopku.org). In Europe, southern countries have the highest predicted response rates based on their most prevalent mutations [34]. It has been shown that missense mutations in the PAH gene induce PAH loss of function by protein misfolding, destabilization and early degradation [41,42]. BH4 was shown to act as a molecular chaperone by increasing the stability of partially misfolded PAH proteins and by this the effective intracellular concentration of functional PAH enzyme [43–46]. It is clear, therefore, that for a patient to respond to BH4, sufficient residual liver PAH protein must be present to interact with BH4. This explains why patients with milder forms and milder mutations are more likely to respond than those with null mutations. It also clarifies why as the phenotype worsens, the response to BH4 is often slow and incomplete. Using mutations to predict residual activity has been successful in predicting BH4-responsiveness [36]. However, responses have been described across the phenotypic spectrum of PAH deficiency, and there are also inconsistencies in the response of patients that share the same genotype, particularly among compound heterozygous (which are the majority of patients) [47,48].

Why are there genotype inconsistencies in the response to BH4? One reason is that different BH4 challenge protocols have been employed by different centers, but these inconsistencies have been described even in the same center. Recent work on PAH enzyme kinetics using a technology that allows for the analysis of a broad range of substrate and cofactor concentrations on PAH activity showed that in addition to the chaperone effect of BH4, kinetic aspects also have to be taken into account [49]. These investigations demonstrate the importance of the relationship between baseline Phe concentrations and the BH4 dose used in the response to a BH4 challenge. In vitro, a given mutation may respond differently when these factors are modified. Since most patients are compound heterozygous, this effect would be magnified. This study suggests that patients with the same genotype can have different responses to BH4 depending on baseline Phe levels or the amount of BH4 administered [49]. In the future, optimal baseline Phe concentrations or the BH4 dose recommendations might have to be individualized. At present, recommendations are standard for all individuals but if a patient with a very suggestive genotype is found to be non-responsive, it is recommended that testing be repeated while taking careful notice of basal Phe levels and/or using longer duration response tests.

BH4 challenge to detect BH4-responsive PAH deficiency is effective at all ages, but there is concern that sensitivity of this testing could be decreased in newborns. After the first 3 months of age, when hepatocytes are sufficiently mature, testing is thought to be reliable. However, testing during the neonatal period has several advantages. It helps in the differential diagnosis of PAH and BH4 deficiencies, but regarding exclusively PKU, it allows the diagnosis of BH4-responsive patients early enough to avoid introducing restrictive diets, favoring breastfeeding and natural protein intake (with better protein, fat, vitamins, microelements and immune composition). During the neonatal period, only short tests (24 h-long) can be used in order to avoid delaying treatment in non-responders. Late-responders can be missed with this protocol; longer term challenges should then be considered at a later age. Although the few publications regarding this subject have not mentioned any side-effects of BH4 in very young patients [50–52], there have been no standardized tests to measure safety in children under 4 years of age. For this reason, the European authorities do not recommend its use in this age group, and the centers that do so must do it under compassionate use.

Once a patient is labeled responsive, considerable effort to fine-tune the therapy is yet required. Continued responsiveness over the long-term must be documented, as fluctuation in blood Phe concentration and unintended alteration of dietary Phe intake during a short-term test may yield false positive results. Improved blood Phe control or a clear increase in dietary Phe tolerance confirm that an individual is truly BH4-responsive, but there is no consensus as to what degree of control or tolerance should be considered as suffient evidence. BH4 treatment must be closely supervised both by the clinician and the dietician during the first year of treatment.

First, the appropriate individualized BH4 dose must be decided. Some studies suggest that the higher the dose, the greater the reduction on Phe levels [53]. For this reason in the US, the trend is to use sapropterin at 20 mg/kg/day. However, other studies suggest that each patient has a dose over which he does not experience any further benefit [54]. European publications tend to suggest the latter, as the dose is titrated to that at which no further tolerance is reached, and patients receive from 5 to 20 mg/kg/day of BH4 [55–60]. The dose per kilo is not age related, but rather it seems affected by the phenotype/genotype of the patient: the milder the phenotype, the smaller the BH4 dose needed for long-term treatment. As with other drugs, there might be a total daily dose, unrelated to weight, over which there is no additional effect of the medication, but no study has been performed to establish such a measure. The maximum dose for obese and adult patients is being decided following each center's protocol, maintaining a dose of 20 mg/ kg/day in some centers, while others use maximum daily doses ranging from 1 g to 1.4 g/day. Few publications indicate that doses higher than 20 mg/kg/day have been tried [60]. No adverse-effects have been reported at these higher doses, but also little additional clinical benefit. It must be noted that animal studies revealed that compound heterozygous mice carrying both a mild and a severe mutation in the PAH gene, Pahenu1/2, show an inhibitory effect at doses above 20 mg/kg/day, whereas this was not true in mice carrying a mild mutation in the homozygous state, Pahenu1/1[61].

Pharmacokinetic studies suggest a peak blood concentration at 2–4 h after ingestion, and a half-life of 6 h[54]. Most patients are treated with single daily dosing, but dividing the total amount in 2–3 daily doses has been suggested to be beneficial for some patients in order to avoid daily Phe level fluctuations [57]. Again, this idea is supported by animal studies, where the in vivo effect of BH4 was significantly shorter in the compound heterozygous mouse Pahenu1/2 than in the homozygous mild phenotype Pahenu1/1[61]. Taking the tablets with food, rather than fasting, has also been proven beneficial [62].

After identification of BH4 responsiveness, the diet must be progressively modified until the highest Phe tolerance possible is determined. The first months of treatment require a very close nutritional follow up, in order to explain the neccesary dietary changes to the family, make sure they implement them and detect any possible food-phobias or misunderstandings that would lead to nutritional deficiencies in the long-term. The usual approach to determine the new Phe tolerance is to give a small amount of extra phenylalanine per week and closely monitor blood Phe levels. Phenylalanine can be administered as natural food, but some centers prefer initially to give only egg or milk powder, as calculation of the increase Phe is more straightforward and it avoids the introduction of foods the patient might like but not be able to tolerate in the long-term. Special Phe-free formulas should be reduced accordingly to the new protein requirements [63]. There are some suggested guidelines as to how to reach the new diet [64], but frequently the patients’ expectations and each center's experience greatly influence the timing and approach to introducing natural foods. In published papers, patients with very mild phenotypes and an important reduction in their Phe levels during the testing period can attain a normal unrestricted diet. However, for patients with more severe phenotypes, a smaller reduction in their Phe levels or a late treatment response, BH4 administration may allow an increase in dietary Phe intake but not fully alleviate the need for a restrictive diet in the long-term [57]. The successfully pharmacologically treated patient will show an increase in dietary Phe tolerance. If this does not occur it is probably due to a false positive result of the treatment test and long-term therapy should be reconsidered. However, there is no clear recommendation for using tolerance as a marker for responsiveness and suggestions vary from a rise in 2 g of daily natural protein, doubling the baseline Phe tolerance or reaching a completely liberalized diet.

After the initial months, patients can be followed with a similar routine as that of any other PKU patient. Few centers have a longer experience with the drug than for a few years [55–60,65,66], but benefits of BH4 other than just the increase in tolerance are starting to be noted, such as a reduction in Phe level fluctuation [58,67] improved growth [58] and improved nutritional status [68,69]. Changes in neuropsychological or quality of life results, although expected to be good, remain to be documented [70,71]. Large scale studies to evaluate long-term outcomes have been initiated, but results will not be known for several years.

Possible negative side-effects are the greatest concern of any pharmacological therapy. During the use of the previously available non-commercial form of BH4, the only published adverse event was mucositis following sublingual administration [72]. Commercialization studies for sapropterin were mainly designed to determine treatment efficacy but no severe adverse events attributable to the drug were reported. [73–75]. In an extension safety study following patients treated with 20 mg/kg/day for several weeks, it was observed that patients complained more often from headache, nasal discharge and gastrointestinal discomfort, mainly nausea and diarrhea. All these symptoms where reported mild and never required the discontinuation of the therapy [53]. Long-term studies need to be conducted to confirm these results and try to establish if side-effects are dose dependant and if other factors such as the diet, age or concomitant medication are involved.

The use of BH4 during pregnancy is an attractive option. In women determined to be BH4-responsive, sapropterin can help reach the strict blood Phe target levels recommended during pregnancy, something all clinicians know is usually not an easy task. In women with the benign form of PKU, who have never followed a protein-restrictive diet and are not accustomed to the taste of the special formulas, sapropterin could offer the perfect solution to their dilemma. Furthermore, avoidance of dietary protein restriction should allow improved nutritional status of the mother, and hence of the fetus. If BH4 is not widely prescribed during pregnancy, it is due to the scanty existing knowledge of the possible teratogenic effect of the medication. A few cases have been published in which no side-effects for the mother or the baby were noted [76]. However, in this report a very low dose of the medication was prescribed (100 to 300 mg/day when the usual dose for an adult PKU patient is 800–1400 mg/day) and there is no long-term safety evidence. The actual recommendation is that diet should be the first option during pregnancy, but when it cannot be followed and/or blood Phe levels are not sufficiently controlled, sapropterin dyhidrocloride treatment can be used.

Many questions remain to be answered regarding the optimum method for evaluating BH4 responsiveness and regarding the long-term benefits of the treatment upon neurological function, nutritional status and the psychosocial well-being of patients. The possibility of adverse events after prolonged treatment and the safety and/or benefits of this therapy in very young children or women during pregnancy and breastfeeding are still to be evaluated [77]. Now that sapropterin is becoming available worldwide, participation in the different ongoing registries is essential in order to gather sufficient data to reach solid conclusions.

3. Phenylalanine ammonia lyase (PAL)

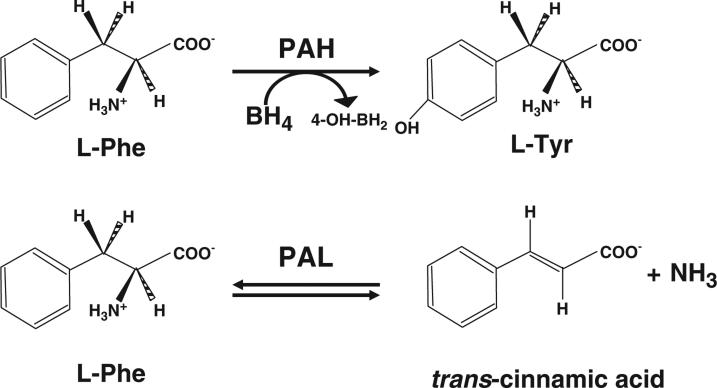

Enzyme substitution therapy with phenylalanine ammonia lyase (PAL; E.C.4.3.1.5) is currently under intensive clinical investigation as a possible alternative treatment for PKU. PAL catalyzes the deamination of phenylalanine to free ammonia and trans-cinnamic acid (Fig. 1) [78]. In humans, trans-cinnamic acid is safely and rapidly converted to hippuric acid which is then excreted in the urine [79]. In comparison to human phenylalanine hydroxylase (PAH), PAL is structurally and catalytically less complex than PAH, physically more stable, and does not require a cofactor. Prior attempts using oral presentations or subcutaneous implantation of PAL-containing bioreactors were unsuccessful [80–82]. However, simple subcutaneous injection of the PAL enzyme into Pahenu2 mice, a model of human PKU, yielded complete correction of blood phenylalanine concentrations [83] and this effect was sustained for up to a year with weekly enzyme injections. PAL from the algae Anabaena variabilis proved physically more resistant to proteolytic degradation, less prone to aggregation, and catalytically more favorable than PAL from other species [84]. Attachment of polyethylene glycol polymers to lysine side chains exposed on the surface of the enzyme (PEGylation) assist to elude immune-mediated detection and elimination of the injected enzyme [85]. Based upon these results, BioMarin Corp., Novato, CA has chosen to move enzyme substitution therapy with PEGylated recombinant Anabaena variabilis PAL (rAvPAL-PEG) into clinical trial. In a Phase 1 trial designed to evaluate safety of subcutaneous rAvPAL-PEG injection and carried out at seven centers in the US, twenty-five adults with PKU and blood phenylalanine>600 μM received a single rAvPAL-PEG injection in escalating dose cohorts. No severe adverse events were recorded and in the highest dose cohort, blood phenylalanine levels decreased significantly after a single rAvPAL-PEG injection (unpublished data). A multi-center Phase 2 clinical trial to assess the safety and efficacy of multiple, repetitive rAvPAL-PEG injections is currently underway. Meanwhile, efforts to develop an effective orally administered rAvPAL-PEG have also been initiated [86].

Fig. 1.

Differences between phenylalanine hydroxylase and phenylalanine ammonia lyase. PAH requires the presence of its cofactor, BH4, as well as a Fe+ molecule and oxygen. PAL does not need a cofactor. Adapted from [78].

4. Gene therapy

The cloning of the human and mouse PAH cDNAs was reported in the 1980s [87]. Early investigations showed that only reaching about 10% enzyme activity is necessary to attain normal Phe metabolism in PAH-deficient mice [88] and recent gene transfer studies using murine models are promising. A recombinant adeno-associated virus (rAAV) vector is frequently employed which produces a lesser immune response than vectors used in early experiments, giving rise to fewer side effects and allowing for longer-term successful treatment. In the mouse model, liver directed gene therapy has allowed for up to one year correction of hyperphenylalaninemia [89,90]. However, liver-directed gene therapy does not lead to a permanent correction of PAH activity. The vector's genome is not integrated in the hepatocyte's DNA and gradual but continuous hepatocyte regeneration eventually leads to elimination of episomal rAAV vector genomes. Reinjection of the same serotype vector is not effective, as it is destroyed by an antibody-mediated immune reaction.

Skeletal muscle is an attractive target organ for gene therapy because it does not suffer on-going cell division and it is more easily accessible. On the other hand, PAH expression alone in myocites will not lead to functional Phe hydroxylation; expression of enzymes involved in the BH4 synthetic pathway an local production of BH4 is also required. This has been tried with promising results in mice [91,92].

The improvement in viral vector design has led to human gene therapy trials for other inborn errors of metabolism, including α1-antitrypsin deficiency, Canavan disease, late-infantile neuronal ceroidlipofuscinosis and lipoprotein lipase deficiency [93]. Ongoing research, optimizing the muscle-directed approach and improving sustainability in liver-directed gene therapy might lead to human trials in PKU in the next few years.

5. Conclusions

Neonatal diagnosis of PKU, early institution of a Phe-restrictive diet and the possibility of avoiding devastating brain damage associated to hyperphenylalaninemia was a great success. Nevertheless, the difficulties of adhering to a strict diet for life and the presence of neurological deficits despite treatment make other therapeutic approaches indispensable. The past decade has been a very exciting time for investigators, clinicians and PKU patients, as the knowledge on the pathogenesis of the disease has been broadened and this has allowed for the investigation of truly novel therapeutic approaches. In some cases, such as dietary products or tetrahydrobiopterin, these novel treatments are already available in the clinical setting. Human trials are underway with rAvPAL-PEG enzyme substitution. Pre-clinical studies are being done in gene and chaperone therapy. Many questions regarding existing therapies remain to be answered and much difficult work has to be done before many of these novel technologies reach the patient, but the future of PKU treatment has never seemed brighter. In the future, different therapies will be available allowing individual treatment depending upon the particular genotype and other personal circumstances such as age or pregnancy.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This article appeared in a journal published by Elsevier. The attached copy is furnished to the author for internal non-commercial research and education use, including for instruction at the authors institution and sharing with colleagues. Other uses, including reproduction and distribution, or selling or licensing copies, or posting to personal, institutional or third party websites are prohibited. In most cases authors are permitted to post their version of the article (e.g. in Word or Tex form) to their personal website or institutional repository. Authors requiring further information regarding Elsevier's archiving and manuscript policies are encouraged to visit: http://www.elsevier.com/copyright

References

- 1.Scriver CR, Kaufman S. Hyperphenylalaninemia: phenylalanine hydroxylase deficiency. In: Scriver CR, Beaudet AL, Valle D, Vogelstein B, Sly WS, editors. The Metabolic and Molecular Bases of Inherited Disease. McGraw-Hill; New York: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Woolf LI. Excretion of conjugated phenylacetic acid in phenylketonuria. Biochem. J. 1951;49:ix–x. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bickel H, Gerrard J, Hickmans EM. Influence of phenylalanine intake on phenylketonuria. Lancet. 1953;265:812–813. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(53)90473-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.National institutes of health consensus development conference statement: phenylketonuria: screening and management. Pediatrics. 2000;108:972–982. doi: 10.1542/peds.108.4.972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Enns GM, Koch R, Brumm V, Blakely E, Suter R, Jurecki e. Suboptimal outcome in patients with PKU treated early with diet alone: revisiting the evidence. Mol. Genet. Metab. 2010;101:99–109. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2010.05.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Levy HL, Waisbren SE, Güttler F, Hanley WB, Matalon R, Rouse B, Trefz FK, de la Cruz F, Azen CG, Koch R. Pregnancy experiences in the woman with mild hyperphenylalaninemia. Pediatrics. 2003;112:1548–1552. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Feillet F, van Spronsen FJ, MacDonald A, Trefz FK, Demirkol M, Giovannini M, Bélanger-Quintana A, Blau N. Challenges and pitfalls in the management of phenylketonuria. Pediatrics. 2010 Aug;126(2):333–341. doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-3584. Epub 2010 Jul 12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Acosta PB, Yannicelli S, Singh R, Mofidi S, Steiner R, DeVincentis E, Jurecki E, Bernstein L, Gleason S, Chetty M, Rouse B. Nutrient intakes and physical growth of children with phenylketonuria undergoing nutrition therapy. J. Am. Diet. Assoc. 2003;103:1167–1173. doi: 10.1016/S0002-8223(03)00983-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Arnold GL, Vladutiu CJ, Kirby RS, m Blakely E, Deluca JM. Protein insufficiency and linear growth restriction in phenylketonuria. J. Pediatr. 2002;141:243–246. doi: 10.1067/mpd.2002.126455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dobbelaere D, Michaud L, Debrabander A, Vanderbecken S, Gottrand F, Turck D, Farriaux JP. Evaluation of nutritional status and pathophysiology of growth retardation in patients with phenylketonuria. J. Inherit. Metab. Dis. 2003;26:1–11. doi: 10.1023/a:1024063726046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Barat P, Barthe N, Redonnet-Vernhet I, Parrot F. The impact of the control of serum phenylalanine levels on osteopenia in patients with phenylketonuria. Eur. J. Pediatr. 2002;161:687–688. doi: 10.1007/s00431-002-1091-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Simon E, Schwarz M, Roos J, Dragano N, Geraedts M, Siegrist J, Kamp G, Wendel U. Evaluation of quality of life and description of the sociodemographic state in adolescent and young adult patients with phenylketonuria (PKU) Health Qual. Life Outcomes. 2008;26:6–25. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-6-25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ahring K, Bélanger-Quintana A, Dokoupil K, Gokmen-Ozel H, Lammardo AM, MacDonald A, Motzfeldt K, Nowacka M, Robert M, van Rijn M. Blood phenylalanine control in phenylketonuria: a survey of 10 European centres. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2011;65:275–278. doi: 10.1038/ejcn.2010.258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.MacDonald A, Gokmen-Ozel H, van Rijn M, Burgard P. The reality of dietary compliance in the management of phenylketonuria. J. Inherit. Metab. Dis. 2010;33:665–670. doi: 10.1007/s10545-010-9073-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Waisbren SE, Noel K, Fahrbach K, Cella C, Frame D, Dorenbaum A, Levy H. Phenylalanine blood levels and clinical outcomes in phenylketonuria: a systematic literature review and meta-analysis. Mol. Genet. Metab. 2007;92:63–70. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2007.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gassió R, Artuch R, Vilaseca MA, Fusté E, Boix C, Sans A, Campistol J. Cognitive functions in classic phenylketonuria and mild hyperphenylalaninaemia: experience in a paediatric population. Dev. Med. Child Neurol. 2005;47:443–448. doi: 10.1017/s0012162205000861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gentile JK, Ten Hoedt AE, Bosch AM. Psychosocial aspects of PKU: hidden disabilities—a review. Mol. Genet. Metab. 2010;99:S64–S67. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2009.10.183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Christ SE, Huijbregts SC, de Sonneville LM, White DA. Executive function in early-treated phenylketonuria: profile and underlying mechanisms. Mol. Genet. Metab. 2010;99:S22–S32. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2009.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sharman R, Sullivan K, Young R, McGill J. Biochemical markers associated with executive function in adolescents with early and continuously treated phenylketonuria. Clin. Genet. 2009;75:169–174. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0004.2008.01101.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Leuzzi V, Pansini M, Sechi E, Chiarotti F, Carducci C, Levi G, Antonozzi I. Executive function impairment in early-treated PKU subjects with normal mental development. J. Inherit. Metab. Dis. 2004;27:115–125. doi: 10.1023/B:BOLI.0000028781.94251.1f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Brumm VL, Bilder D, Waisbren SE. Psychiatric symptoms and disorders in phenylketonuria. Mol. Genet. Metab. 2010;99:S59–S63. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2009.10.182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Matalon R, Michals-Matalon K, Bhatia G, Burlina AB, Burlina AP, Braga C, Fiori L, Giovannini M, Grechanina E, Novikov P, Grady J, Tyring SK, Guttler F. Double blind placebo control trial of large neutral aminoacids in treatment of PKU: effect on blood phenylalanine. J. Inherit. Metab. Dis. 2007;30:153–158. doi: 10.1007/s10545-007-0556-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ney DM, Gleason ST, van Calcar SC, MacLeod EL, Nelson KL, Etzel MR, Rice GM, Wolff JA. Nutritional management of PKU with glycomacropeptide from cheese whey. J. Inherit. Metab. Dis. 2009;32:32–38. doi: 10.1007/s10545-008-0952-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Harding CO, Gibson KM. Therapeutic liver repopulation for phenylketonuria. J. Inherit. Metab. Dis. 2010;33:681–687. doi: 10.1007/s10545-010-9099-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hyghland K. Tetrahydrobiopterin deficiencies with hyperphenylalaninemia. In: Blau N, editor. PKU and BH4. Advances in Phenylketonuria and Tetrahydrobiopterin. SPS Publications; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Niederwieser A, Curtius HC, Wang M, Leupold D. Atypical phenylketonuria with defective biopterin metabolism. Monotherapy with tetrahydrobiopterin or sepiapterin, screening and study of biosynthesis in man. Eur. J. Pediatr. 1982;138:110–112. doi: 10.1007/BF00441135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kure S, Hou DC, Ohura T, Iwamoto H, Suzuki S, Sugiyama N, Sakamoto O, Fujii K, Matsubara Y, Narisawa K. Tetrahydrobiopterin-responsive phenylalanine hydroxylase deficiency. J. Pediatr. 1999;135:375–378. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(99)70138-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bernegger C, Blau N. High frequency of tetrahydrobiopterin-responsiveness among hyperphenylalaninemias: a study of 1,919 patients observed from 1988 to 2002. Mol. Genet. Metab. 2002;77:304–313. doi: 10.1016/s1096-7192(02)00171-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Muntau AC, Röschinger W, Habich M, Demmelmair H, Hoffmann B, Sommerhoff CP, Roscher AA. Tetrahydrobiopterin as an alternative treatment for mild phenylketonuria. N. Engl. J. Med. 2002;347:2122–2132. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa021654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lindner M, Steinfeld R, Burgard P, Schulze A, Mayatepek E, Zschocke J. Tetrahydrobiopterin sensitivity in German patients with mild phenylalanine hydroxylase deficiency. Hum. Mutat. 2003;21:400. doi: 10.1002/humu.9117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Desviat LR, Pérez B, Bèlanger-Quintana A, Castro M, Aguado C, Sánchez A, García MJ, Martínez-Pardo M, Ugarte M. Tetrahydrobiopterin responsiveness: results of the BH4 loading test in 31 Spanish PKU patients and correlation with their genotype. Mol. Genet. Metab. 2004;83:157–162. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2004.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Matalon R, Michals-Matalon K, Koch R, Grady J, Tyring S, Stevens RC. Response of patients with phenylketonuria in the US to tetrahydrobiopterin. Mol. Genet. Metab. 2005;86:S17–S21. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2005.06.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mitchell JJ, Wilcken B, Alexander I, Ellaway C, O'Grady H, Wiley V, Earl J, Christodoulou J. Tetrahydrobiopterin-responsive phenylketonuria: the New South Wales experience. Mol. Genet. Metab. 2005;86:S81–S85. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2005.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zurflüh MR, Zschocke J, Lindner M, Feillet F, Chery C, Burlina A, Stevens RC, Thöny B, Blau N. Molecular genetics of tetrahydrobiopterin-responsive phenylalanine hydroxylase deficiency. Hum. Mutat. 2008;29:167–175. doi: 10.1002/humu.20637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dobrowolski SF, Borski K, Ellingson CC, Koch R, Levy HL, Naylor EW. A limited spectrum of phenylalanine hydroxylase mutations is observed in phenylketonuria patients in western Poland and implications for treatment with 6R tetrahydrobiopterin. J. Hum. Genet. 2009;54:335–359. doi: 10.1038/jhg.2009.37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Karacić I, Meili D, Sarnavka V, Heintz C, Thöny B, Ramadza DP, Fumić K, Mardesić D, Barić I, Blau N. Genotype-predicted tetrahydrobiopterin (BH4)-responsiveness and molecular genetics in Croatian patients with phenylalanine hydroxylase (PAH) deficiency. Mol. Genet. Metab. 2009;97:165–171. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2009.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Blau N, Bélanger-Quintana A, Demirkol M, Feillet F, Giovannini M, MacDonald A, Trefz FK, van Spronsen FJ. Optimizing the use of sapropterin (BH(4)) in the management of phenylketonuria. Mol. Genet. Metab. 2009;96:158–163. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2009.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Levy H, Burton B, Cederbaum S, Scriver C. Recommendations for evaluation of responsiveness to tetrahydrobiopterin (BH(4)) in phenylketonuria and its use in treatment. Mol. Genet. Metab. 2007;92:287–291. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2007.09.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Fiege B, Bonafé L, Ballhausen D, Baumgartner M, Thöny B, Meili D, Fiori L, Giovannini M, Blau N. Extended tetrahydrobiopterin loading test in the diagnosis of cofactor-responsive phenylketonuria: a pilot study. Mol. Genet. Metab. 2005;86:S91–S95. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2005.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Okano Y, Takatori K, Kudo S, Sakaguchi T, Asada M, Kajiwara M, Yamano T. Effects of tetrahydrobiopterin and phenylalanine on in vivo human phenylalanine hydroxylase by phenylalanine breath test. Mol. Genet. Metab. 2007;92:308–314. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2007.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pey AL, Stricher F, Serrano L, Martinez A. Predicted effects of missense mutations on native-state stability account for phenotypic outcome in phenylketonuria, a paradigm of misfolding diseases. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2007;81:1006–1024. doi: 10.1086/521879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gersting SW, Kemter KF, Staudigl M, Messing DD, Danecka MK, Lagler FB, Sommerhoff CP, Roscher AA, Muntau AC. Loss of function in phenylketonuria is caused by impaired molecular motions and conformational instability. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2008;83:5–17. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2008.05.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Erlandsen H, Pey AL, Gámez A, Pérez B, Desviat LR, Aguado C, Koch R, Surendran S, Tyring S, Matalon R, Scriver CR, Ugarte M, Martínez A, Stevens RC. Correction of kinetic and stability defects by tetrahydrobiopterin in phenylketonuria patients with certain phenylalanine hydroxylase mutations. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2004;101:16903–16908. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0407256101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pey AL, Pérez B, Desviat LR, Martínez MA, Aguado C, Erlandsen H, Gámez A, Stevens RC, Thórólfsson M, Ugarte M, Martínez A. Mechanisms underlying responsiveness to tetrahydrobiopterin in mild phenylketonuria mutations. Hum. Mutat. 2004;24:388–399. doi: 10.1002/humu.20097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Pérez B, Desviat LR, Gómez-Puertas P, Martínez A, Stevens RC, Ugarte M. Kinetic and stability analysis of PKU mutations identified in BH4-responsive patients. Mol. Genet. Metab. 2005;86:S11–S16. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2005.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gersting SW, Lagler FB, Eichinger A, Kemter KF, Danecka MK, Messing DD, Staudigl M, Domdey KA, Zsifkovits C, Fingerhut R, Glossmann H, Roscher AA, Muntau AC. Pahenu1 is a mouse model for tetrahydrobiopterin-responsive phenylalanine hydroxylase deficiency and promotes analysis of the pharmacological chaperone mechanism in vivo. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2010;19:2039–2049. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddq085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hennermann JB, Bührer C, Blau N, Vetter B, Mönch E. Long-term treatment with tetrahydrobiopterin increases phenylalanine tolerance in children with severe phenotype of phenylketonuria. Mol. Genet. Metab. 2005;86:S86–S90. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2005.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Trefz FK, Scheible D, Götz H, Frauendienst-Egger G. Significance of genotype in tetrahydrobiopterin-responsive phenylketonuria. J. Inherit. Metab. Dis. 2009;32:22–26. doi: 10.1007/s10545-008-0940-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Staudigl M, Gersting SW, Danecka MK, Messing DD, Woidy M, Pinkas D, Kemter KF, Blau N, Muntau AC. The interplay between genotype, metabolic state and cofactor treatment governs phenylalanine hydroxylase function and drug response. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2011 doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddr165. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Feillet F, Chery C, Namour F, Kimmoun A, Favre E, Lorentz E, Battaglia-Hsu SF, Guéant JL. Evaluation of neonatal BH4 loading test in neonates screened for hyperphenylalaninemia. Early Hum. Dev. 2008;84:561–567. doi: 10.1016/j.earlhumdev.2008.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Bik-Multanowski M, Pietrzyk JJ, Didycz B, Szymczakiewicz-Multanowska A. Development of a model for assessment of phenylalanine hydroxylase activity in newborns with phenylketonuria receiving tetrahydrobiopterin: a potential for practical implementation. Mol. Genet. Metab. 2008;94:389–390. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2008.03.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Burton BK, Adams DJ, Grange DK, Malone JI, Jurecki E, Bausell H, Marra KD, Sprietsma L, Swan KT. Tetrahydrobiopterin therapy for phenylketonuria in infants and young children. J. Pediatr. 2011;158:410–415. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2010.08.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lee P, Treacy EP, Crombez E, Wasserstein M, Waber L, Wolff J, Wendel U, Dorenbaum A, Bebchuk J, Christ-Schmidt H, Seashore M, Giovannini M, Burton BK, Morris AA. Sapropterin Research Group, Safety and efficacy of 22 weeks of treatment with sapropterin dihydrochloride in patients with phenylketonuria. Am. J. Med. Genet. A. 2008;15:2851–2859. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.32562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Feillet F, Clarke L, Meli C, Lipson M, Morris AA, Harmatz P, Mould DR, Green B, Dorenbaum A, Giovannini M, Foehr E. Sapropterin Research Group, Pharmacokinetics of sapropterin in patients with phenylketonuria. Clin. Pharmacokinet. 2008;47:817–825. doi: 10.2165/0003088-200847120-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Cerone R, Schiaffino MC, Fantasia AR, Perfumo M, Birk Moller L, Blau N. Long-term follow-up of a patient with mild tetrahydrobiopterin-responsive phenylketonuria. Mol. Genet. Metab. 2004;81:137–139. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2003.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Lambruschini N, Pérez-Dueñas B, Vilaseca MA, Mas A, Artuch R, Gassió R, Gómez L, Gutiérrez A, Campistol J. Clinical and nutritional evaluation of phenylketonuric patients on tetrahydrobiopterin monotherapy. Mol. Genet. Metab. 2005;86:S54–S60. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2005.05.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Bélanger-Quintana A, García MJ, Castro M, Desviat LR, Pérez B, Mejía B, Ugarte M, Martínez-Pardo M. Spanish BH4-responsive phenylalanine hydroxylasedeficient patients: evolution of seven patients on long-term treatment with tetrahydrobiopterin. Mol. Genet. Metab. 2005;86:S61–S66. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2005.07.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Trefz FK, Scheible D, Frauendienst-Egger G, Korall H, Blau N. Long-term treatment of patients with mild and classical phenylketonuria by tetrahydrobiopterin. Mol. Genet. Metab. 2005;86:S75–S80. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2005.06.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Bóveda MD, Couce ML, Castiñeiras DE, Cocho JA, Pérez B, Ugarte M, Fraga JM. The tetrahydrobiopterin loading test in 36 patients with hyperphenylalaninaemia: evaluation of response and subsequent treatment. J. Inherit. Metab. Dis. 2007;30:812. doi: 10.1007/s10545-007-0567-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Trefz FK, Scheible D, Frauendienst-Egger G. Long-term follow-up of patients with phenylketonuria receiving tetrahydrobiopterin treatment. J. Inherit. Metab. Dis. 2010;9 doi: 10.1007/s10545-010-9058-x. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Lagler FB, Gersting SW, Zsifkovits C, Steinbacher A, Eichinger A, Danecka MK, Staudigl M, Fingerhut R, Glossmann H, Muntau AC. New insights into tetrahydrobiopterin pharmacodynamics from Pah enu1/2, a mouse model for compound heterozygous tetrahydrobiopterin-responsive phenylalanine hydroxylase deficiency. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2010;80:1563–1571. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2010.07.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Musson DG, Kramer WG, Foehr ED, Bieberdorf FA, Hornfeldt CS, Kim SS, Dorenbaum A. Relative bioavailability of sapropterin from intact and dissolved sapropterin dihydrochloride tablets and the effects of food: a randomized, open-label, crossover study in healthy adults. Clin. Ther. 2010;32:338–346. doi: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2010.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Macdonald A, Ahring K, Dokoupil K, Gokmen-Ozel H, Lammardo AM, Motzfeldt K, Robert M, Rocha JC, van Rijn M, Bélanger-Quintana A. Adjusting diet with sapropterin in phenylketonuria: what factors should be considered? Br. J. Nutr. 2011;5:1–8. doi: 10.1017/S0007114511000298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Singh RH, Jurecki E, Rohr F. Recommendations for personalized diet adjustments based on patients response to tetrahydrobiopterin (BH4) in phenylketonuria. Top. Clin. Nutr. 2008;23:149–157. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Shintaku H, Kure S, Ohura T, Okano Y, Ohwada M, Sugiyama N, Sakura N, Yoshida I, Yoshino M, Matsubara Y, Suzuki K, Aoki K, Kitagawa T. Long-term treatment and diagnosis of tetrahydrobiopterin-responsive hyperphenylalaninemia with a mutant phenylalanine hydroxylase gene. Pediatr. Res. 2004;55:425–430. doi: 10.1203/01.PDR.0000111283.91564.7E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Shintaku H, Ohwada M, Aoki K, Kitagawa T, Yamano T. Diagnosis of tetrahydrobiopterin (BH4) responsive mild phenylketonuria in Japan over the past 10 years. Ann. Acad. Med. Singapore. 2008;37:77–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Burton BK, Bausell H, Katz R, Laduca H, Sullivan C. Sapropterin therapy increases stability of blood phenylalanine levels in patients with BH4-responsive phenylketonuria (PKU) Mol. Genet. Metab. 2010;101:110–114. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2010.06.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Singh RH, Quirk ME, Douglas TD, Brauchla MC. BH(4) therapy impacts the nutrition status and intake in children with phenylketonuria: 2-year follow-up. J. Inherit. Metab. Dis. 2010;33:689–695. doi: 10.1007/s10545-010-9224-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Vilaseca MA, Lambruschini N, Gómez-López L, Gutiérrez A, Moreno J, Tondo M, Artuch R, Campistol J. Long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acid status in phenylketonuric patients treated with tetrahydrobiopterin. Clin. Biochem. 2010;43:411–415. doi: 10.1016/j.clinbiochem.2009.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Gassió R, Vilaseca MA, Lambruschini N, Boix C, Fusté ME, Campistol J. Cognitive functions in patients with phenylketonuria in long-term treatment with tetrahydrobiopterin. Mol. Genet. Metab. 2010;99:S75–S78. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2009.10.187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Somaraju UR, Merrin M. Sapropterin dihydrochloride for phenylketonuria. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2010;16:CD008005. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD008005.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Opladen T, Zurflüh M, Kern I, Kierat L, Thöny B, Blau N. Severe mucitis after sublingual administration of tetrahydrobiopterin in a patient with tetrahydrobiopterin-responsive phenylketonuria. Eur. J. Pediatr. 2005;164:395–396. doi: 10.1007/s00431-005-1638-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Burton BK, Grange DK, Milanowski A, Vockley G, Feillet F, Crombez EA, Abadie V, Harding CO, Cederbaum S, Dobbelaere D, Smith A, Dorenbaum A. The response of patients with phenylketonuria and elevated serum phenylalanine to treatment with oral sapropterin dihydrochloride (6R-tetrahydrobiopterin): a phase II, multicentre, open-label, screening study. J. Inherit. Metab. Dis. 2007;30:700–707. doi: 10.1007/s10545-007-0605-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Levy HL, Milanowski A, Chakrapani A, Cleary M, Lee P, Trefz FK, Whitley CB, Feillet F, Feigenbaum AS, Bebchuk JD, Christ-Schmidt H, Dorenbaum A, Sapropterin Research Group Efficacy of sapropterin dihydrochloride (tetrahydrobiopterin, 6R-BH4) for reduction of phenylalanine concentration in patients with phenylketonuria: a phase III randomised placebo-controlled study. Lancet. 2007;370:504–510. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61234-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Trefz FK, Burton BK, Longo N, Casanova MM, Gruskin DJ, Dorenbaum A, Kakkis ED, Crombez EA, Grange DK, Harmatz P, Lipson MH, Milanowski A, Randolph LM, Vockley J, Whitley CB, Wolff JA, Bebchuk J, Christ-Schmidt H, Hennermann JB. Sapropterin Study Group, Efficacy of sapropterin dihydrochloride in increasing phenylalanine tolerance in children with phenylketonuria: a phase III, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. J. Pediatr. 2009;154:700–707. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2008.11.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Koch R. Maternal phenylketonuria and tetrahydrobiopterin. Pediatrics. 2008;122:1367–1368. doi: 10.1542/peds.2008-2783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Trefz FK, Belanger-Quintana A. Sapropterin dihydrochloride: a new drug and a new concept in the management of phenylketonuria. Drugs Today. 2010;46:589–600. doi: 10.1358/dot.2010.46.8.1509557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Kim W, Erlandsen H, Surendran S, Stevens RC, Gamez A, Michols-Matalon K, Tyring SK, Matalon R. Trends in enzyme therapy for phenylketonuria. Mol. Ther. 2004;10:220–224. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2004.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Hoskins JA, Holliday SB, Greenway AM. The metabolism of cinnamic acid by healthy and phenylketonuric adults: a kinetic study. Biomed. Mass Spectrom. 1984;11:296–300. doi: 10.1002/bms.1200110609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Hoskins JA, Jack G, Wade HE, Peiris RJ, Wright EC, Starr DJ, Stern J. Enzymatic control of phenylalanine intake in phenylketonuria. Lancet. 1980;1:392–394. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(80)90944-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Safos S, Chang TM. Enzyme replacement therapy in ENU2 phenylketonuric mice using oral microencapsulated phenylalanine ammonia-lyase: a preliminary report. Artif. Cells Blood Substit. Immobil. Biotechnol. 1995;23:681–692. doi: 10.3109/10731199509117980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Ambrus CM, Ambrus JL, Horvath C, Pedersen H, Sharma S, Kant C, Mirand E, Guthrie R, Paul T. Phenylalanine depletion for the management of phenylketonuria: use of enzyme reactors with immobilized enzymes. Science. 1978;201:837–839. doi: 10.1126/science.567372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Sarkissian CN, Gamez A, Wang L, Charbonneau M, Fitzpatrick P, Lemontt JF, Zhao B, Vellard M, Bell SM, Henschell C, Lambert A, Tsuruda L, Stevens RC, Scriver CR. Preclinical evaluation of multiple species of PEGylated recombinant phenylalanine ammonia lyase for the treatment of phenylketonuria. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2008;105:20894–20899. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0808421105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Sarkissian CN, Shao Z, Blain F, Peevers R, Su H, Heft R, Chang TM, Scriver CR. A different approach to treatment of phenylketonuria: phenylalanine degradation with recombinant phenylalanine ammonia lyase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1999;96:2339–2344. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.5.2339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Gamez A, Wang L, Sarkissian CN, Wendt D, Fitzpatrick P, Lemontt JF, Scriver CR, Stevens RC. Structure-based epitope and PEGylation sites mapping of phenylalanine ammonia-lyase for enzyme substitution treatment of phenylketonuria. Mol. Genet. Metab. 2007;91:325–334. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2007.04.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Kang TS, Wang L, Sarkissian CN, Gámez A, Scriver CR, Stevens RC. Converting an injectable protein therapeutic into an oral form: phenylalanine ammonia lyase for phenylketonuria. Mol. Genet. Metab. 2010;99:4–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2009.09.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Woo SL, Lidsky AS, Güttler F, Chandra T, Robson KJ. Cloned human phenylalanine hydroxylase gene allows prenatal diagnosis and carrier detection of classical phenylketonuria. Nature. 1983;306:151–155. doi: 10.1038/306151a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Ledley FD, Grenett HE, DiLella AG, Kwok SC, Woo SL. Gene transfer and expression of human phenylalanine hydroxylase. Science. 1985;228:77–79. doi: 10.1126/science.3856322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Harding CO, Gillingham MB, Hamman K, Clark H, Goebel-Daghighi E, Bird A, Koeberl DD. Complete correction of hyperphenylalaninemia following liver-directed, recombinant AAV2/8 vector-mediated gene therapy in murine phenylketonuria. Gene Ther. 2006;13:457–462. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3302678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Ding Z, Georgiev P, Thöny B. Administration-route and gender-independent long-term therapeutic correction of phenylketonuria (PKU) in a mouse model by recombinant adeno-associated virus 8 pseudotyped vector-mediated gene transfer. Gene Ther. 2006;13:587–593. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3302684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Ding Z, Harding CO, Rebuffat A, Elzaouk L, Wolff JA, Thöny B. Correction of murine PKU following AAV-mediated intramuscular expression of a complete phenylalanine hydroxylating system. Mol. Ther. 2008;16:673–681. doi: 10.1038/mt.2008.17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Rebuffat A, Harding CO, Ding Z, Thöny B. Comparison of adeno-associated virus pseudotype 1, 2, and 8 vectors administered by intramuscular injection in the treatment of murine phenylketonuria. Hum. Gene Ther. 2010;21:463–477. doi: 10.1089/hum.2009.127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Alexander IE, Cunningham SC, Logan GJ, Christodoulou J. Potential of AAV vectors in the treatment of metabolic disease. Gene Ther. 2008;15:831–839. doi: 10.1038/gt.2008.64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]