The late 2000s economic crisis has transformed Europe. Scholars and politicians concur with the longstanding economic, political, and social consequences of this crisis. The financial meltdown shrunk traditionally large economies and left a few of them at the verge of bankruptcy. The South of Europe, in particular, is one of the regions in the world where the consequences of the crisis have become most salient. Governmental efforts to face the crisis have generated deep institutional changes and historical turning points for the welfare state, democratic representation, labor relations, and social protests. The economic crisis has shifted the structure of the political field, allowing the rise of new political actors and novel alignments on both new and old political issues. In the midst of these transformations, we have attempted to compile a collection of scholarly analyses that seek to examine the most important institutional and social shifts taking place today in Southern Europe.

Greece, Italy, Portugal, and Spain have experienced two parallel crises of different types—an economic crisis and a political one. These two crises cannot be examined in isolation: the institutional response to face the former has provoked the latter. These economic and political crises are both national and transnational. Since 2009, the European Union has encouraged Southern European nations to implement a political agenda of austerity, in exchange for financial assistance. These policies have reduced the state’s participation in the economy and, in turn, increased unemployment rates. Moreover, a monetary policy aimed at maintaining a high euro–U.S. dollar parity has been especially detrimental to the primary and secondary sectors of Southern Europe. Low economic activity, high unemployment, low consumption, and the declining role of the state have generated a new economic scenario with unpredictable consequences. Increasing inequality, rising social unrest, weakening public institutions, and growing political disaffection question the extent to which Southern European democracies can maintain their legitimacy. In this special issue, we attempt to provide insightful and critical examinations of the most important transformations in Southern Europe today.

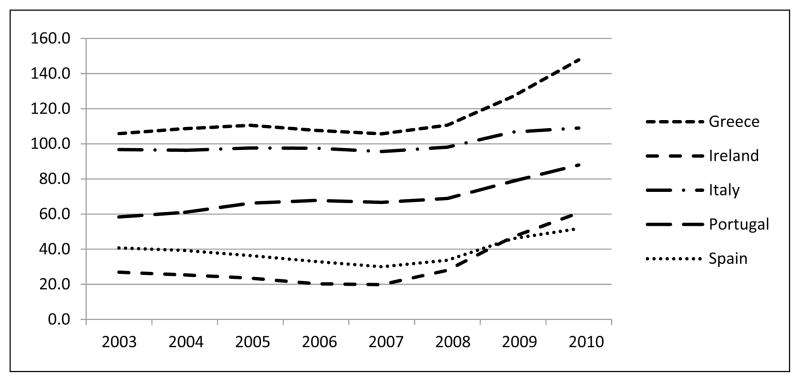

Data from Table 1 and Figure 1 introduce the historical significance of central government debt. We observe that some countries in the European South multiplied their debt two- and three-fold between 1980 and 2010. The relative size of these increases is much larger than other European economies, such as Sweden, but comparable to others, such as Germany. The debt of Greece and Italy represented more than 100% of its gross domestic product (GDP) before the year 2000, which questions the extent to which these economies have the tools to become financially solvent in the near future. Portugal and Spain followed, with economies characterized by slightly lower levels of debt, but they exhibited similar difficulties in reducing their financial dependence. The articles in this special issue examine central government debt as one of the starting points to examine current transformations in the fields of immigration and public administration, the quality of democracy, and the political and institutional responses to the crisis.

Table 1.

Central Government Debt (% of Gross Domestic Product) in Six European Countries, 1980–2010.

| 1980 | 1990 | 2000 | 2010 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Germany | 13.0 | 19.7 | 38.4 | 44.4 |

| Greece | — | 97.6a | 108.9 | 147.8 |

| Italy | 52.7 | 92.8 | 103.6 | 109.0 |

| Portugal | 29.2 | 51.7 | 52.1 | 88.0 |

| Spain | 14.3 | 36.5 | 49.9 | 51.7 |

| Sweden | 38.2 | 39.6 | 56.9 | 33.8 |

Source: OECD Stat Extracts and World Economic Outlook Database of the International Monetary Fund, accessed January 3, 2013.

Data for 1993.

Figure 1.

Total central government debt in Southern Europe and Ireland (as % of gross domestic product [GDP]), 2003–2010.

Source: OECD Stat Extracts, Total central government debt as a percentage of the GDP, 2011, accessed July 16, 2013 (http://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/finance-and-investment/total-central-government-debt_20758294-table1).

Austerity has been the most common strategy to reduce debt. Table 2 illustrates the effect of these regulations at the household level. Greeks, Irish, and Portuguese have suffered the largest cuts; in 2011, austerity measures reduced the average household income in Greece by 14%, and almost 7% in Ireland and Portugal. Spaniards and Italians followed, with household income reductions of about 5% and 3%, respectively. Austerity policies are widening the gap between the rich and the poor and engendering new forms of inequality that have received little scholarly attention. The Gini index in Europe went from 29 in the year 2000 (15 countries) to 30.6 in 2012 (25 countries), and within Europe, we know that it is specifically in the South of Europe where inequality is increasing the most. For instance, between 2000 and 2012, the Gini index in Greece went from 33 to 34.3, in Spain from 32 to 35, and in Italy from 29 to 31.9. Portugal is the only Southern European country that managed to reduce overall inequality despite the crisis; Portugal’s Gini index went from 36 to 34.5 between 2000 and 2012.1 Unemployment is one of the most important causes of today’s growing inequality.

Table 2.

Austerity in Europe, 2011.

| Austerity Package per Household (€) | Austerity Package as % Take-Home Household Income | Austerity Tax and Levy Increase per Household (€) | Austerity Package as % GDP per Head | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Germany | 283 | 0.7 | 134 | 0.4 |

| Greece | 5,647 | 13.7 | 2,898 | 11.1 |

| Ireland | 3,602 | 6.7 | 840 | 3.8 |

| Italy | 1,131 | 2.7 | 468 | 1.8 |

| Portugal | 2,166 | 6.7 | NA | 5.0 |

| Spain | 1,962 | 4.8 | 506 | 3.1 |

| United Kingdom | 1,355 | 3.2 | 692 | 2.0 |

Note. GDP = gross domestic product; NA = data not available.

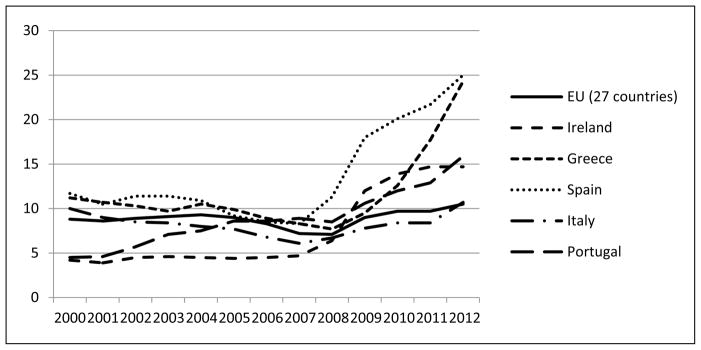

Greece and Spain exhibit exceptionally high unemployment rates, followed by Portugal and Italy (see Table 3 and Figure 2). From a macro-economic perspective, high unemployment implies low consumption and less revenue for both the public and private sectors. Moreover, unemployment begins a vicious economic circle to increasing poverty, growing inequality, out-migration, and civil unrest. The economic crisis is transforming traditional understandings of political actors and institutions. Citizens have expressed increasing disaffection toward traditional representative democracy and, in turn, have encouraged the rise of alternative forms of conducting politics. Greece’s Golden Dawn, Italy’s 5 Star movement, Spain’s 15-M, and Portugal’s Fuck Troika! provide preliminary illustrations of the novel forms of social discontent that have emerged to express disagreement with the institutional management of the crisis. Shrinking Southern European economies and weakening democratic institutions encourage scholars and politicians to evaluate the extent to which the South of Europe might be facing an unprecedented systemic crisis.

Table 3.

Unemployment Rates (%).

| 2012

|

2013

|

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mar | Sept | Oct | Nov | Dec | Jan | Feb | Mar | |

| Euro area (17) | 11.0 | 11.6 | 11.7 | 11.8 | 11.8 | 12.0 | 12.0 | 12.1 |

| European Union (27) | 10.3 | 10.6 | 10.7 | 10.7 | 10.7 | 10.9 | 10.9 | 10.9 |

| Greece | 21.5a | 25.9 | 25.9 | 26.5 | 25.7 | 27.2 | NA | NA |

| Spain | 24.1 | 25.7 | 26.0 | 26.2 | 26.2 | 26.4 | 26.5 | 26.7 |

| Italy | 10.4 | 10.9 | 11.2 | 11.2 | 11.2 | 11.7 | 11.5 | 11.5 |

| Portugal | 15.1 | 16.4 | 16.8 | 17.0 | 17.3 | 17.5 | 17.5 | 17.5 |

| United States | 8.2 | 7.8 | 7.9 | 7.8 | 7.8 | 7.9 | 7.7 | 7.6 |

Source: Eurostat (http://europa.eu/rapid/press-release_STAT-13-70_en.htm).

Note. NA = data not available.

January 2012.

Figure 2.

Unemployment rates in Southern Europe and Ireland, 2000–2012.

Source: Unemployment rates, Eurostat, accessed July 16, 2013 (http://epp.eurostat.ec.europa.eu/tgm/table.do?tab=table&init=1&plugin=1&language=en&pcode=tsdec450).

The goal of this special issue is to introduce some of the most important socioeconomic and political transformations that are taking place in Southern Europe from the analytical lenses of outstanding Southern European scholars. De Sousa, Magalhaes, and Amaral (p. 1517) used survey data to examine how Portuguese citizens responded to the political management of the crisis and found an unprecedented growing discontent toward Portugal’s young democracy. These findings are consistent with the comparative analysis carried out by Mariano Torcal (p. 1542). Torcal used evidence from Portugal and Spain to show the extent to which the political management of the economic crisis has deepened an increasing distrust in political institutions. This distrust is mainly based on negative perceptions of the institutions’ responsiveness function that, in the case of Spain, is multiplied by the perception of corruption among politicians. Similarly, Sebastián Royo (p. 1568) used an economic approach to explain the economic crisis as a result of an institutional degeneration process that had taken place before the crisis even began.

Evidence from Greece and Ireland reveals to what extent the citizenry and the government have reacted to the crisis differently. As Pappas and O’Malley (p. 1592) discussed, whereas Ireland showed a high level of acceptance of the new scenario defined by the crisis, Greece witnessed the emergence of “political luddism,” sometimes violent collective actions addressed to the state actors. The explanation lies in the different ways the Irish and the Greek governments have had to manage the crisis and provide public goods to the citizenry. In Greece and Italy, as Triandafyllidou and Gropas’s (p. 1614) e-survey shows, the crisis led to novel out-migration flows. Highly qualified Greeks and Italians felt severely deprived and frustrated with the situation of their respective home countries and decided to explore new professional opportunities abroad. Brain drain is not just one more consequence of the economic crisis in Southern European countries but a novel demographic shift with critical long-term implications.

In Italy, Di Mascio and Natalini (p. 1634) showed the extent to which the government cut social expenditure while reducing public employment and the implications of these issues for citizens’ quality of life. The analysis reveals that a reduced workforce has had to provide increasing public services with shrinking resources. Morlino and Piana (p. 1657) provided a complementary perspective to this phenomenon, with an examination of what they called “stalemated democracy.” The authors provided evidence of the extent to which, in Italy, political representatives tried to use old answers to address the uncertainty of the shifting political and institutional arena. The governmental management of the crisis, one more time, encouraged the citizens to question the legitimacy of democratic institutions and political representatives.

With this special issue, we seek to shed light on some of the most important transformations changing Southern Europe today. Our aim is to present new hypotheses and insights to gain understanding of the structural change taking place in Southern Europe today. Due to space constraints, the collection of articles included in this special issue provides only a preliminary introduction to these structural transformations. The authors analyze, in-depth, political disaffection, new patterns of inequality, declining institutional legitimacy, economic austerity and welfare state retrenchment, and the rise of in- and out-migration flows. These seminal examinations will be useful for present and future scholars interested in Southern Europe, because they illustrate the causes and consequences of a social Zeitgeist. We would like to thank Laura Lawrie, for her enthusiasm, support, and interest in this project since its inception, as well as all participating authors for their passion and commitment to this collective project. Thank you.

Footnotes

The source for the Gini index is the Eurostat series, accessed March 2014 (http://epp.eurostat.ec.europa.eu/tgm/table.do?tab=table&plugin=0&language=en&pcode=tessi190).

References

- Gainsbury S, Whiffin A, Birkett R. Financial pain in Europe. Financial Times. 2011 Oct 17; retrieved from http://www.ft.com/cms/s/0/feb598a8-f8e8-11e0-a5f7-00144feab49a.html#axzz2xqP3xBqx.