Abstract

By the 1990s, sociology faced a frustrating paradox. Classic work on mental illness stigma and labeling theory reinforced that the “mark” of mental illness created prejudice and discrimination for individuals and family members. Yet that foundation, coupled with deinstitutionalization of mental health care, produced contradictory responses. Claims that stigma was dissipating were made, while others argued that intervention efforts were needed to reduce stigma. While signaling the critical role of theory-based research in establishing the pervasive effects of stigma, both claims directed resources away from social science research. Yet the contemporary scientific foundation underlying both claims was weak. A reply came in a resurgence of research directed toward mental illness stigma nationally and internationally, bringing together researchers from different disciplines for the first time. The author reports on the general population’s attitudes, beliefs, and behavioral dispositions that targeted public stigma and implications for the next decade of research and intervention efforts.

Keywords: stigma, mental illness, sociology of mental health, General Social Survey, discrimination

In the 1993 Emmy-winning HBO movie And the Band Played On, epidemiologists from multiple disciplines, including public health, medicine, and sociology, confronted the rising infection and staggering death rate from the disease that would later be known as HIV/AIDS.1 Actor Charles Martin Smith played Dr. Harold Jaffe, who in 1981 became an epidemic intelligence service officer, joining the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) task force assigned to study the earliest cases. At several points during the film, he asks, “What do we think? What do we know? What can we prove?” This refrain seems an apt borrow from the CDC to apply here because stigma research, policies, and programs surrounding mental illness have been based on answers to each of these questions, and not always to good result.

The past few decades have witnessed continuity and change in our understanding of and response to the stigma of mental illness. Declarations by leaders in psychiatry that stigma has dissipated in the United States, for example, implied that neither research nor social action of any kind was necessary (Pescosolido et al. 2010). The work had been done, the problem solved. At the same time, National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) program staff members, convinced of the continued trauma that stigma leveled on individuals, advised researchers that only the development and evaluation of clinical or community interventions were high priorities.

Across the globe, research at the population level continued (e.g., Angermeyer, Daeumer, and Matschinger 1993; Bailey 1998; Jorm et al. 1997; Stuart and Arboleda-Florez 2001), efforts to reduce prejudice and discrimination continued (e.g., the Rosalynn Carter Fellowships for Mental Health Journalism, established in 1995), and new initiatives at the World Psychiatric Association (the Open the Door Programme; Sartorius 1997) took shape. There were those in the sociology of mental health who continued their research agendas on stigma (Link et al. 1997; Rosenfield 1997; Thoits 1985), new sociological researchers attacked the problem (Markowitz 1998), and others outside the discipline did the same, all adding important insights to knowledge (Corrigan and Penn 1999; Estroff 1981; Fabrega 1991).

Yet the paradox of U.S.-based sociological research on stigma flagging from the mid-1970s through the early 1990s, while claims about positive cultural change were becoming common, was not lost on sociologists (Pescosolido, McLeod, and Avison 2007). In direct response to claims that seemed socially implausible, casually observational, and stunningly narrow, sociologists responded as part of what might legitimately be constructed as a resurgent effort to understand the contemporary challenge of stigma. The past few decades have witnessed renewed efforts, including the 1999 White House Conference on Mental Health, the surgeon general’s report on mental health (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services 1999), and the President’s New Freedom Commission on Mental Health (2003). Targeted programs were developed (e.g., the 2001 Fogarty International Center Conference and RFA on Stigma [Michels et al. 2006]; the 2004 NIMH program Reducing Mental Illness Stigma and Discrimination), research-based conferences held (the Together Against Stigma International Conferences, first in Leipzig, Germnay, in 2001; Stuart 2008), and new antistigma efforts begun (the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration’s Web-based ADS Center and What a Difference a Friend Makes campaign; California’s Proposition 63 initiative).2

The research focus on the cultural landscape of stigma—for both adults and children with mental health problems; at the local, national, and international levels; and for documenting change across decades—represents a major part of sociologists’ research contributions to this resurgence. In this article, I use Dr. Jaffe’s pointed questions to review the current status of sociological understandings of mental illness stigma. Although the foci are primarily on public stigma and sociology, this line is not drawn narrowly or pristinely. Furthermore, given that the sociology of mental health motivates this discussion, only a brief background of classic theories already well known to sociologists is provided. The remainder follows directly, though in opposite order, from the CDC’s questions: a review of findings from the resurgence (What can we prove?), a consideration of how this shapes our research agenda (What do we know but cannot prove?), and calls for different research or policy recommendations (What do we think but do not know?).

A BRIEF THEORETICAL BACKGROUND

By 1960, Goffman had laid out his thesis about individual action, public reaction, and identity in The Presentation of Self in Everyday Life (Goffman 1959). He argued for the centrality of face-to-face interactions, noting that mismatches between self and others’ perceptions held the potential to discredit individuals. He turned his attention specifically to issues of identity and interaction regarding mental illness in Asylums: Essays on the Social Situation of Mental Patients and Other Inmates (Goffman 1961). As a visiting member of the NIMH’s Laboratory of Socio-Environmental Studies (1954–1957), he did a year of participant observation fieldwork, in a minor staff position, at St. Elizabeth’s Hospital, the federal psychiatric hospital in Washington, DC, which according to Goffman once housed over 7,000 individuals. He entered this research setting “with no great respect for the discipline of psychiatry nor for agencies content with its current practice” (Goffman 1961:x). In “Characteristics of Total Institutions,” he contrasted the situation of “staff” and “inmates,” noting, however, the tendency of both “to conceive of the other in terms of narrow hostile stereotypes,” with “staff often seeing inmates as bitter, secretive, and untrustworthy” and inmates, themselves, tending “in some ways at least, to feel inferior, weak, blameworthy, and guilty” (Goffman 1961:7). He described the moral career, the process of “stripping” identity, the mortification of self, “discrediting” events recorded in case histories, and the “irrevocable” loss of roles that “may be painfully experienced” by patients (Goffman 1961:128, 158, 15).

But stigma received only passing mention. Goffman did not extend his research into the community, as his colleague and lab director John Clausen did at that time. However, he argued that, upon release from the hospital, an individual’s “social position on the outside will never again be quite what it was prior to entrance,” because “the total institution bestows an unfavorable status” (Goffman 1961:72). And here Goffman first noted, “we can employ the term ‘stigmatization.’” He suggested that the stigma of hospitalization yields “a cool reception in the wider world,” especially under circumstances “hard even for those without his stigma when he must apply for a job and a place to live” (Goffman 1961:73). More important, perhaps, he anticipated notions of provider-based stigma, arguing that “an important kind of leverage possessed by the staff is their power to give the kind of discharge that reduces stigmatization,” which, for the “mental patient,” is a “clean bill of health” (Goffman 1961:73).

In Stigma: Notes on the Management of Spoiled Identity Goffman (1963) focused on a wide range of statuses (e.g., orphan, criminal) that engender negative stereotypes and prejudice. He provided the now standard definition of stigma, an accounting of basic types, and the theoretical fundamentals widely used in research and practice. Stigma is a “mark” that signals to others that an individual possesses an attribute reducing him or her from “whole and usual” to “tainted and discounted.” This devaluation translates into seeing the stigmatized person as “less than fully human” and may emanate from “abominations of the body” (physical deformities), “blemishes of individual character” (mental illness, addictions, government aid), and “tribal identities” (race, gender, religion). Importantly, Goffman reinforced his earlier view that stigma, though arising from an attribute marking difference, can be enacted only in social interaction and is typified by exclusion from full participation in society. Finally, he saw the nature and effects of stigma not as static but as having an ebb and flow in concert with other aspects of an individual’s “moral career” and the larger societal context (Hinshaw 2006:24ff; Pescosolido and Martin 2007; Scambler 2011).

Although many date the beginning of serious sociological attention to stigma to Goffman (1963), in reality, a number of streams of work preceded it in sociological importance (Pescosolido and Martin 2007).3 However, the major target of prejudice and discrimination research in social science has been race: what Myrdal (1944), the Swedish economist and Nobel laureate, called the classic “American dilemma.” Referring to the “Negro problem” and its clash with fundamental tenets of equality in modern democracy, he focused on the obstacles to societal participation raised by racial stereotypes. In psychology, Allport’s (1954) Nature of Prejudice defined the subfield of intergroup relations, the study of prejudice, and the research agenda on group interactions, bringing ethnic stereotyping into the scientific mainstream (Dovidio, Glick, and Rudman 2005). However, as Pettigrew and Tropp (2000) pointed out, sociologist Robin Williams (1947), in response to a Social Science Research Council request, earlier laid out over 100 propositions on reducing racial prejudice through intergroup contact. Williams argued that prejudice arises from a fear of a “threatening other” or from an exploitative system, that social conditions would produce either a weakened or an empowered minority group, that situational norms could facilitate or prohibit prejudicial behavior, that relaxed informal interactions paradoxically lead to greater formalized controls, and that “emotional moments” were followed by “routine drift toward acceptance” (Kohn and Williams 1956; Williams 1965).

Yet even at this early point, the lack of shared intellectual discussion across sociology’s subfields, which Collins (1986) decried much later, was already apparent. Goffman (1961:40) knew and cited The American Soldier (Stouffer et al. 1949), a project in which Williams participated, and which reported a quasi-experimental analysis documenting decreased racial prejudice in integrated units. Yet theoretical and empirical work on intergroup relations did not have much of a crossover influence on early research on “stigma,” and contemporary work on race does not reference the term. Stigma research, including Goffman’s, grew out of different sociological research traditions, primarily deviance and social control, professions and institutions, and identity theory. Psychology’s social psychology continued to focus on a wide variety of “targets,” including race, class, and mental illness (e.g., Dovidio et al. 2005) but had little contact with either sociological stream. It would be part of the resurgence of the late 1990s to bring these together.

A BRIEF EMPIRICAL BACKGROUND

Preceding Goffman’s inductively derived frame, two early, influential sociological studies on public recognition of and response to mental illness appeared in the 1950s. In the American Sociological Review, Woodward (1951) reported data on a representative population sample of Louisville, Kentucky. While contending ironically that “the sense of the stigma associated with mental illness is passing” (p. 445), more than half of respondents, particularly those who were older and less well educated, reported an unwillingness to disclose mental health problems or to recognize the need for treatment, because “the very fact of mental illness involves a stigma which makes people resist the fact of facing psychosis” (p. 452). Four years later, Star (1955) produced a mimeographed report on the first nationally representative study of Americans’ knowledge of and attitudes toward mental illness. Pioneering the use of vignettes in her National Opinion Research Center–based survey, she documented what was either a profound inability to recognize mental illness or a reluctance to label described individuals as mentally ill. Importantly, she asked an open-ended question, “What is mental illness?” to which the public responded by describing primarily symptoms associated with severe psychosis. Other important studies followed, targeting local areas in the United States, towns in Canada, and various populations (e.g., Cumming and Cumming 1957; Nunnally 1961; Weinstein 1983).

In sociology, much of the dialogue on stigma was a by-product of the development and critique of labeling theory; for example, motivating the classic debate between Gove and Scheff on whether the “behaviors” or the “label” were the root cause of stigma (Hinshaw 2006, chap. 5; Pescosolido and Martin 2007). On the basis of this debate and bringing important new data on individuals with serious mental illness to light, Link et al. (1989) developed modified labeling theory. Arguing that societal labels did not “produce” chronic mental illness, as Scheff (1966) claimed, they documented that the label had profound stigmatizing effects on individuals’ lives.

Outside sociology, two path-breaking studies were fielded at the University of Michigan’s Institute for Social Research. Although not “stigma” studies per se, the first Americans View Their Mental Health (AVTMH) nationwide survey, sponsored by the Joint Commission on Mental Illness and Health, provided critical information on public understanding of and response to mental illness, including if they had “ever anticipated having a nervous breakdown” and what they did in response. Gurin, Veroff, and Field (1960) documented fairly low levels of informal and formal help-seeking, with individuals as likely to seek out a lawyer or member of the clergy as a psychiatrist. A 1976 follow-up repeated the survey on a new representative sample, finding a general increase in “readiness for self-referral” and in the (still low) use of mental health professionals for all groups. Social class differences continued to shape defining a problem as relevant for help and in adopting an active coping style. Education and income differences in the specific use of psychiatrists and psychologists continued, although the gap between high- and low-income groups narrowed (Kulka, Veroff, and Douvan 1979; Veroff, Douvan, and Kulka 1981).

THE RESURGENCE IN THE SOCIOLOGICAL STUDY OF PUBLIC STIGMA

Sociological research on stigma and its presence in major journals of the discipline waned as the behavior-label debate lost steam without resolution. Research on other issues in the sociology of mental health, particularly life events, distress, and disorder, not only continued but appeared to take on new energy, even as sociologists argued about the research utility of psychiatric diagnoses (Mirowsky and Ross 1989). although the classic Epidemiological Catchment Area studies had always brought sociologists into contact with those in psychiatry and other mental health disciplines, the late 1980s brought a greater emphasis on multidisciplinarity. This expedited sociologists’ growing awareness of the widespread, but undocumented, claim of decreasing stigma. A team from Indiana University and Columbia University brought this observation and an argument for new social data to the Overseers Board of the General Social Survey (GSS), the longest running monitor of American public attitudes, perceptions, and self-reported behaviors.4 Requesting a standard 15-minute “module” on public stigma, the team laid out the potential to follow up on classic studies as well as a new approach matching changes in the science of mental health problems, treatment, and stigma. Over the decade from 1996 to 2006, a series of five GSS modules were fielded that, in whole or in part, tapped into the stigma of mental illness as reflected in perceived attributions, stereotypes, help-seeking, and behavioral predispositions (Table 1).

Table 1.

General Social Survey Studies on mental Health, mental Illness, and Stigma

| Study | Description |

|---|---|

| Methodology | |

| General Social Survey | Nationally representative sample of noninstitutionalized adults living in the contiguous United States (n ≈ 1,500, response rate ≈ 75 percent) |

| Vignette based | Alcohol dependence, major depressive disorder, schizophrenia, drug dependence, troubled person, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, childhood depression, asthma, daily troubles |

| Studies | |

| 1996 macArthur mental Health module | 57-item interview schedule of questions focused on knowledge, attitudes, and beliefs about the causes, consequences, and treatment of mental health problems |

| 1998 Pressing Issues in Health and medical Care module | Relevant questions focused on assessment of the efficacy of psychiatric medications and willingness to use them |

| 2002 National Stigma Study–Children | Assesses attitudes toward the causes and treatment of mental health problems among children and teenagers |

| 2006 National Stigma Study–Replication | Replication of the 1996 mental health study assessing stigma change over a decade |

| 2006 Stigma in Global Context–mental Health Study | U.S. component of 15-country study of cultural context of mental illness knowledge, treatment, and prejudice |

The 1996 MacArthur Mental Health Module drew inspiration from the Star and AVTMH studies. Indeed, we were privileged to travel to the National Opinion Research Center, where one in three original Star surveys had been archived, and to the University of Michigan, where Toni Antonucci graciously gave us access to the original AVTMH surveys. Relevant parts of the original surveys, open-ended text responses, were copied (in Star’s study, “What is mental illness?” and in the AVTMH studies, “Have you ever anticipated a ‘nervous breakdown’?” and “What did you do?”), but no codes in existing data files were used. Temporal context, itself, would have differentially shaped the cultural frame that coders brought to the data. To provide a rigorous evaluation of change, both the original and the new 1996 data were coded using the same categories and procedures.

For newly designed sections, social desirability and political correctness combined with greater population knowledge to make statements about “mental patients,” “the mentally ill,” or even specific designations of “people with schizophrenia” inadequate on two grounds. First, we could not be sure what referents respondents brought to questions (e.g., any severe mental illness, phobias, personality disorders, child/adult problems). Second, providing a label would prohibit gathering data on a critical issue that motivated the study: problem recognition, part of mental health literacy. Aware of limitations, a vignette strategy using Diagnostic and Statistical Manual, Fourth Edition, criteria, the standard American Psychiatric Association guide to psychiatric diagnoses, was developed. This same module was repeated in the 2006 National Stigma Study–Replication (NSS-R), dropping the drug dependence vignette to increase statistical power and eliminating what we considered a flaw in the original vignette (i.e., reference to possible “criminal” behavior, stealing).

In 1998, the GSS included several health-related mini-modules, with mental health questions targeting views on the efficacy of psychotropic medications and willingness to use them. In 2002, the GSS fielded the first national study on public recognition of and response to child mental health issues. The National Stigma Study–Children (NSS-C) was composed of a vignettes describing child diagnoses of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), depression, asthma, and “daily troubles”; statements on community perceptions of children with mental health problems and their families; and views of ADHD and its treatment (Perry and Pescosolido 2011). In 2006, the GSS also included the U.S. component of the Stigma in Global Context–Mental Health Study (SGC-MHS) on the second sample. The multicountry, theoretically and methodologically coordinated study included three vignettes (schizophrenia, major depression, and asthma; Pescosolido, Olafsdottir, et al. 2008).

WHAT CAN WE PROVE? A SET OF BASIC FINDINGS

Although prove may be too strong a word given the pioneering nature of the GSS and SGC-MHS (i.e., without replication by other data), these surveys on public stigma provide findings that are both important and, given data quality, sound.

Finding Set 1: The “Good News”—Over the Long Haul, the Public Has Become Somewhat More Sophisticated and Perhaps More Open to Disclosure, Recognition, and Response about Mental Health Problems

When responses to the open-ended question “What is mental illness?” were compared between the 1950 Star study and the 1996 GSS, it was seen that the public had broadened its conception. According to Phelan et al. (2000), the earlier study found a narrow range of problems consistent with psychiatric notions of psychosis, anxiety, and depression. Specifically, although these have not disappeared from the public mind (40.7 percent in 1950; 34.9 percent in 1996 on psychosis), they now include a greater number and range of mental health problems, including substance abuse (from 7.1 percent to 15.5 percent), developmental disorders (from 6.5 percent to 13.8 percent), and other nonpsychotic problems (from 7.1 percent to 20.1 percent).

Furthermore, by 1996, a majority endorsed newer neuroscientific views for schizophrenia (77.8 percent chemical imbalance, 61.1 percent genetics) and depression (68.3 percent chemical imbalance, 50.8 percent genetics; Pescosolido, Boyer, and Lubell 1999). Figure 1A shows that from 1996 to 2006 even more Americans reported neurobiological attributions as causes of depression (chemical imbalance, genetics), schizophrenia (chemical imbalance, genetics), and alcohol dependence (genetics; i.e., increasing percentages indicated by upward bars; significance indicated when the confidence interval does not cross the zero point).5 Importantly, trend analyses in other Western countries supported this finding as a global change in public sophistication (e.g., Angermeyer and Matschinger 2005 in Germany; see Pescosolido et al. 2010 for a review with similar conclusions for Turkey, Russia, Mongolia, Australia, and Austria).

Figure 1.

Raw Changes in Selected Attributions, Treatment Recommendations, and Social Distance Venue by Vignette Type, 1996 to 2006, U.S. General Social Survey

Note: Graphs indicate the differences in the 1996 and 2006 unadjusted percentages. Tick marks indicate 95 percent confidence intervals. Data are from the mental health modules of the 1996 and 2006 General Social Surveys and are weighted.

Even with controversies over children’s mental health diagnoses (Pescosolido 2007), NSS-C results also suggested acceptance of psychiatric views. McLeod et al. (2007) reported that 64 percent of the U.S. population had heard of ADHD, and of those, 78 percent reported it as a “real” disorder. For depression, 69.3 percent reported that the vignette described a child with mental health issues, with over half (58.5 percent) identifying it specifically as depression (Pescosolido, Jensen, et al. 2008). The public also clearly separated “daily troubles” and asthma from ADHD or depression in problem recognition and assessments of severity (Martin et al. 2007). Finally, most recommended service use at even higher rates than for adults (Perry and Pescosolido 2011). For ADHD, however, most reported a decided tendency to combine medication and counseling strategies (65 percent; McLeod et al. 2007).

These “positive” changes were echoed in key findings on adults’ changing responses to their self-reported mental health problems. Table 2, comparing raw and adjusted responses to the AVTMH question on “anticipated” nervous breakdown,6 revealed a gradual and significant increase (Swindle et al. 2000). These numbers cannot be read as changes in the lifetime prevalence of mental health problems in the strict epidemiological sense. Rather, they mark an increase in self-report, which may indicate more mental health difficulties or greater mental health knowledge, better problem recognition, and/or greater willingness to disclose. From a stigma perspective, whatever the underlying reason, the change is notable.

Table 2.

Americans’ Self-Reports of “Nervous Breakdown” and Coping Responses over Time

| 1957 AVTmH | 1976 AVTmH | 1996 GSS | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Self-reported “nervous breakdown” (percent) | |||

| Raw | 18.9 | 20.9 | 26.4 |

| Adjusted | 17.0 | 19.6 | 24.3 |

| Participants’ coping responses (percent) | |||

| Approacha | 12.5 | 20.1 | 31.6 |

| Avoidance | 27.8 | 24.4 | 29.0 |

| Informal supporta | 6.5 | 12.4 | 28.3 |

| formal support | 48.1 | 49.8 | 42.0 |

Source: Reproduced with permission from Swindle et al. (2000).

Both raw and adjusted change significant at p ≤ .05.

Comparisons over time also suggested a greater embrace of active and informal responses. Although analyses revealed little change in the share of individuals who chose to do “nothing” (avoidance), or who sought out professionals (formal support; Table 2), significantly more individuals reported a proactive approach (nearly tripling the percentage from 1957 to 1996) and an almost fourfold increase in the willingness to talk to family and friends. Furthermore, although not displayed here, a large increase in using nonmedical mental health professionals such as “psychologists,” “counselors,” and “social workers” was also in evidence (Swindle et al. 2000).

More recently, the NSS-R continued to document positive change in treatment recommendations. Unlike the earlier AVTMH changes, the public’s increased willingness to suggest treatment appeared to be squarely in the medical domain (Figure 1B). Significantly more Americans endorsed the use of physicians and prescription medication for all scenarios, psychiatrists for depression and alcohol dependence, and the hospital for schizophrenia. Already high levels of endorsement, in both years, suggested other ceiling effects (e.g., schizophrenia-psychiatrist).

Finding Set 2: The “Bad News”—Stigma Is Alive and Well with Relatively Stable Gradients, Little Change over Time, and Surprising Adult-Child Comparisons

Although recognition, attributions, and service use may reflect prejudice associated with mental illness, the heart of stigma lies in social acceptance, rejection, and the power to influence both (Link and Phelan 2001). Table 3 presents selected findings on social distance for adults (1996 GSS) and children and adolescents (2002 GSS).

Table 3.

Stigmatizing Attitudes toward Adults and Children by Vignette Type and Social Venue, U.S. General Social Surveys, 1996 and 2002

| Vignette Type | Percent Unwilling to | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adultsa | Move next door | Make friends with | Spend an evening socializing with | Work closely with on the job | marry into your family |

| Troubled person | 9.5 | 10.0 | 14.9 | 21.0 | 41.9 |

| Depression | 22.9 | 23.1 | 37.8 | 48.6 | 60.6 |

| Schizophrenia | 37.0 | 34.0 | 49.0 | 64.1 | 72.2 |

| Alcohol dependence | 45.6 | 36.7 | 55.8 | 74.7 | 78.2 |

| Drug dependence | 75.0 | 59.1 | 72.7 | 82.0 | 89.0 |

| Children/adolescents | Have child as classmate | Spend an evening with family | Move next door | make friends with | |

| Asthma | 2.80 | 6.45 | 9.31 | 4.82 | |

| “Daily troubles” | 5.95 | 10.49 | 10.49 | 9.79 | |

| Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder | 19.30 | 16.90 | 22.19 | 23.47 | |

| Depression | 11.04 | 17.48 | 18.45 | 29.64 | |

Adapted with permission from martin et al. (2000).

Adapted with permission from martin et al. (2007).

For both, the percentage of respondents expressing rejection is much lower for the “troubled person” and the child with “daily troubles” or asthma.7 The public can differentiate between “problems of daily living” and standard psychiatric categories. However, stigma levels for the latter were substantial and by no means suggested the “dissipation” of stigma alluded to in research and policy statements. At least in Western nations, findings from representative regional and national studies on adult issues were remarkably similar (e.g., Crisp et al. 2000; Stuart and Arboleda-Florez 2001). For children and adolescents, percentages were notably lower, but still substantial, ranging from 11 percent (classmate, depression) to 29 percent (friendship, depression). However, fully half of respondents reported that prejudice would follow as a consequence of mental health treatment, having immediate and long-term negative effects on children’s futures (Perry and Pescosolido 2011; Pescosolido, Perry, et al. 2007).

For both children and adults, stigmatizing responses appeared along two gradients: nature of the problem and social venue. First, the percentage of respondents endorsing stigmatizing responses increased from “troubled person” to depression to schizophrenia to alcohol dependence, and finally, to drug dependence in both 1996 and 2006 (Pescosolido et al. 2010; Pescosolido, Olafsdottir, et al. 2008; also Silton et al. 2011). For children, there is also a gradient, but the clear split appeared between mental health and non–mental health issues. ADHD and depression engendered the highest levels at which rejection switches off between the two. Second, the more “intimate” the setting, the more respondents reported rejection. For adults, working closely on the job and having the vignette person marry into the family produced stigma from more of the public than socializing or friendship. The gradient is not pristine, especially for the substance abuse vignettes, for which living next door produced a greater stigmatizing response than friendship. Yet the results clearly revealed that the likelihood of experiencing rejection was not the same across all spheres of social life. For children, the gradient was not as pronounced; however, “friendship” elicited the highest negative public responses, especially for depression.

Confronting assumptions of change

Much of the motivation for the U.S. GSS studies was to empirically assess claims about decreasing stigma. Comparisons over time revealed increasing stigma on one key issue and no recent improvement on another. Specifically, perceptions of potential violence as a fundamental component of mental illness had not decreased; rather, if anything, data suggested a significant increase between 1950 and 1996 in spontaneous mentions of “danger” or “violence” in response to “What is mental illness?” (Phelan et al. 2000). Furthermore, among respondents who mentioned violence, the specific phrasing of “dangerous to self and others” increased. Link, Castille, and Stuber (2008) noted the irony of the public using this language, because it was originally adopted to protect the civil liberties of individuals with mental illnesses. Translated into popular use as a way to understand the essence of mental illness, it reflects a negative stereotype seen across the GSS studies (Pescosolido, Fettes, et al. 2007; Pescosolido, Monahan, et al. 1999). In fact, Olafsdottir’s (2011) analysis of newspaper accounts suggested that this was more characteristic of the United States than other Western countries. Her comparison of the cultures of “fear,” “retribution,” and “solidarity” revealed that nearly half (46 percent) of U.S. stories on mental illness directly mention or alluded to violence, whereas only 12 percent did so in both Germany and Iceland (also Pilgrim and Rogers 2011).

Despite improvements in mental health literacy, NSS-R analyses were unable to document decreases in public rejection from 1996 to 2006. In no venue and for no mental health problem did reports of social distance decrease. In one case (i.e., schizophrenia, live next door), the raw percentages actually increased, though this effect did not persist in the face of controls (Figure 1C; Pescosolido et al. 2010). Neither Payton and Thoits (2011) nor Schnittker (2008), also analyzing GSS data, found evidence of improvement, nor did a recent meta-review across a large number of studies globally (Schomerus et al. 2012).

An unexpected difference: the public response to child and adolescent depression

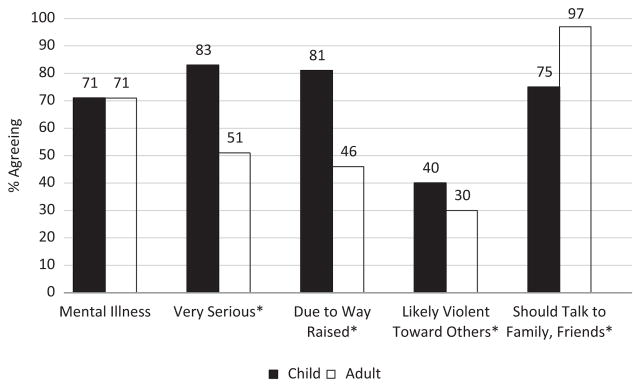

In general, public reaction suggested greater tolerance toward children and adolescents compared with adults with mental health problems. Yet the one case for which a direct and specific comparison was possible revealed that childhood depression engendered negative sentiments from more respondents on nearly every count. Although equally assigning mental illness labels, more respondents saw childhood depression as very serious, unlikely to improve without treatment, due to child rearing, and signaling a potential for violence (Figure 2). This may reflect a lack of recognition of adult depression, a greater tolerance for prevalent adult mental health problems, or a by-product of media coverage of school shooting incidents. Examining these possibilities was beyond the limits of GSS data but tempered our initial conclusions on comparisons between children and adults.

Figure 2.

Comparison of Public Responses to Child (2002, n = 312) and Adult (1996, n = 193) Depression, U.S. General Social Survey

Source: Adapted with permission from Perry et al. (2007).

*Significant at p ≤ .05.

Finding Set 3: Debates Resolved, Assumptions Questioned, Predictions Fulfilled

In stigma research, some issues became flash-points because they pitted hypotheses against each other or because they were implicit or explicit foundations for stigma reduction efforts. Among the most important to which the research resurgence could contribute, three are addressed here: the Scheff-Gove debate, the underlying assumptions of most stigma reduction campaigns, and the power of sociodemographics to guide targeted campaigns.

Is it labels or behaviors? The essence of the 1970s debate between Gove and Scheff was whether stigma arises from nonnormative behaviors that constitute mental illness symptomatology or from cultural meanings attached to the label of mental illness that trigger prejudice. But by 1999, Link and Phelan (1999) characterized the either-or debate over the power of labeling versus behavior as unproductive. By including both Diagnostic and Statistical Manual, Fourth Edition, consistent behaviors and questions on labels of physical illness, mental illness, and “ups and downs” of life, this debate could be adjudicated, perhaps for the first time, though not without limits.

Both factors were significantly associated with stigmatizing responses. Different vignettes elicited different levels of social distance in line with the gradients described earlier. Thus, behaviors mattered in terms of the probability of social rejection. Furthermore, individuals who endorsed the vignette as a “mental illness” were also more likely to give stigmatizing responses. Thus, the label of mental illness mattered, even controlling for behavior. These effects were documented for both adults (Martin, Pescosolido, and Tuch 2000; Silton et al. 2011) and children (Martin et al. 2007). In fact, when respondents evoked the label of mental illness, a cascade of effects followed, playing a key role in shaping assessment of treatment need, including medication recommendations from virtually any provider that they were willing to consult (Perry and Pescosolido 2011; Pescosolido, Jensen, et al. 2008). However, respondents endorsing mental illness were twice as likely to report a potential for violence and five times as likely to support coercive treatment as well as express a preference for greater social distance (Pescosolido, Fettes, et al. 2007). As Rosenfield (1997) alluded to earlier with regard to the centrality of stigma in debates about labeling theory, the reality is more complex than either proponents or critics anticipated.

Questioning the dominant “tag line” of stigma reduction: the ironic role of neurobiology

The GSS studies did not support the expected link between the public acceptance of neurobiological attributions and more tolerant attitudes (Pescosolido et al. 2010). Posited as a major lever of stigma reduction, the National Alliance on Mental Illness held as a central tenet the idea that when the public understood mental illness as a “real” disease, on par with cancer or diabetes, caused by biology and genetics, prejudice and discrimination would fade. “A disease like any other” formed the implicit or explicit message of antistigma campaigns, which focused heavily on education (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services 1999).

NSS-R findings documented the success of educational messaging. The public’s mental health literacy had increased significantly and, by 2006, was at high levels. Yet the association between attributions and lower stigma was nowhere in evidence. Whether analyses targeted the individual or aggregate link between “modern” attributions and stigma (in both 1996 and 2006), there was no support that greater scientific understanding translated into reduced prejudice in the United States or elsewhere (Angermeyer and Matschinger 2005; Schomerus et al. 2012).

In fact, neurobiological attribution had complex, mixed, and even contradictory effects (Phelan et al. 2006). Endorsing genetic attributions seemed to increase public support for help-seeking (e.g., hospitals, medications but not physicians, psychiatrists) but engendered greater pessimism on treatment efficacy (Schnittker 2008; Schnittker, Freese, and Powell 2000). Most important, Phelan (2005) suggested a backlash effect. Genetic attribution was often significantly associated with higher levels of stigma, perhaps because the mark conveyed a sense of permanence, having effects that live on in families past the time of any one individual.

The limited role of sociodemographics

Findings on stigma revealed little that could be systematically explained by social characteristics. These factors were unreliable, inconsistent, or impotent predictors, unlike in Woodward’s (1951) study, in which age and education were associated with attitudes. Age was only occasionally related to attitudes (e.g., greater endorsement of clergy for help, though not for schizophrenia; Ellison et al. 2006), and education was rarely significant (Watson, Corrigan, and Angell 2005).

There were, of course, some issues on which sociodemographics mattered. Knowledge of ADHD was lower for men, African Americans, and those with less education (McLeod et al. 2007). Overall, the influence of race and gender were mixed. African Americans were less likely than whites to suggest medical treatment for vignette children (Pescosolido, Jensen, et al. 2008) and to report a willingness to use psychiatric medication (Schnittker 2003). For adults, they were significantly more likely to reject genetic and family attributions, but not chemical imbalance or stress (Schnittker et al. 2000). They reported either no difference or a greater willingness for treatment, sometimes expressing greater optimism about health care outcomes (Schnittker, Pescosolido, and Croghan 2005). On gender, women vignette characters were seen as less dangerous, but female respondents did not differ on expressions of social distance or danger (Schnittker 2000). Even for child problems, for which the effects of respondents’ gender, marital status, or parenthood might be expected, no significant influences were documented (Pescosolido, Jensen, et al. 2008; Pescosolido and Olafsdottir 2010).

Overall, differences in public responses centered on cultural attitudes, valuations of the situation, and occasionally on social location (Olafsdottir and Pescosolido 2009; Phelan 2005). And in some cases in which the direct effects of sociodemographics were documented, the effects disappeared when attributions were taken into account. For example, men sometimes reported greater desire for social distance from children with mental health problems, but this was mediated by their greater endorsement of “lack of discipline,” “bad character,” and perceived danger (Pescosolido, Jensen, et al. 2008).

These findings are relevant not only to the sociology of mental health and to sociology as a whole but to research and practical efforts to reduce stigma. GSS findings suggest that targeting sociodemographic groups as the blueprint for future campaigns might be too loosely couple research to programming (e.g., basing the NIMH’s 2003 Real Men, Real Depression campaign on research documenting that men are less likely to seek help for mental health problems).

WHAT DO WE KNOW BUT CAN’T PROVE? RETHINKING CULTURE AND CULTURAL CONTEXT

The resurgence simultaneously represented progress and laid bare research limitations, raising concerns about measuring the culture of stigma. Some analyses offered tentative insights and signaled new directions for the next phase of stigma research.

How Do We Measure Cultural Predispositions Thought to Reflect Stigma?

Looking to GSS findings on treatment endorsement, a naive conclusion suggests that cultural barriers to help-seeking for mental health problems have been dismantled. Public treatment recommendations revealed very high levels of accepting formal and informal sources of care. However, even as preeminent psychiatric epidemiological studies documented a reduction from one in five to one in four individuals in need receiving care for mental health (Wang et al. 2005), the continued mismatch between “need” and “use” stands in stark contrast to GSS findings.

Standard explanations can be offered: the well-known lack of attitude-behavior links, the existence of access barriers that foil individuals’ ability to act on predispositions, and the distinct difference between suggesting treatment for “others” versus seeking care oneself. In fact, hints of the latter possibility appeared in 1998 GSS findings on psychiatric medications. The overwhelming majority (60 percent to 75 percent) reported positive opinions on the efficacy of psychiatric medications, including relatively few reporting concerns with side effects. Yet the proportion willing to use them, even when faced with quite severe symptoms (e.g., intense fear, losing control) was notably low in contrast (26.5 percent very likely; Croghan et al. 2003).

In response, we repurposed GSS data on treatment endorsement, asking not whether respondents supported the use of treatment providers but whether analyses by attributions, assessments, and sociodemographics revealed cleavages among endorsements. In fact, beliefs about causes and consequences demarcated important lines. For example, although perceived severity led respondents to endorse any source of care, in line with past utilization research (Pescosolido et al. 1998), those who endorsed biological causation were significantly more likely to endorse general or specialty medical providers. Assessments of potential danger were associated with greater support for specialists (psychiatrists, hospitalization) over others. Although respondents endorsed multiple treatment options, they clearly discriminated among them, suggesting that a more nuanced cultural schema lay hidden under the typically high and unrealistic treatment endorsements (Olafsdottir and Pescosolido 2009).

We drew on these findings to modify measurement in later GSS modules. Looking to the “cultural turn” in sociology, the NSS-C included an open-ended utilization question (“suggestions”) placed immediately after the vignette and the usual closed-ended set (“endorsements”) in similar placement as earlier efforts. We hypothesized that the former required respondents to actively search for options using deliberative processing and reflecting individuals’ cognitive toolbox of strategies, whereas the latter required only a passive posture using automatic processing and reflecting larger cultural values. Overall, spontaneous mentions were more in line with actual service use rates and sociodemographic proxies thought to measure cultural differences (Pescosolido and Olafsdottir 2010).

Our efforts focused on measurement, not method. Surveys are capable of capturing cultural issues. Design changes, even within large-scale surveys, offered a promising start for integrating new conceptualizations of culture into research on how individuals respond to mental illness.

How Are Larger Cultures Connected to Individual-Level Stigma?

Individuals in every society have a reservoir of embedded knowledge and attitudes used to address problems in their lives and those of family and friends. If equating “culture” with sociodemographic characteristics is problematic, then a reconsideration of “whole cultural systems,” including larger cultural climates, is in order (Olafsdottir and Pescosolido 2009). The resurgence included cross-national research on societal profiles of stigma; however, differences or similarities could only be inferred with great caution.

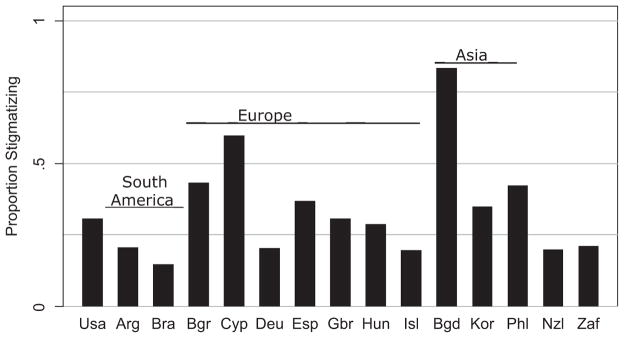

Only recently have data become available to address two critical questions: Do larger cultural contexts of stigma differ significantly? Does this matter for individuals? Speaking to the first issue, preliminary findings from the SGC-MHS suggest that they do. Even in regions expected to have greater cultural similarities (Europe), levels of recognition and prejudice show significant variation in public response to mental illness (Olafsdottir and Pescosolido 2011; Pescosolido, Olafsdottir, et al. 2008). Basic descriptive results (Figure 3) reveal significant differences not easily explained by geography (under a diffusion perspective) or even GDP (under a world systems perspective). The population proportion indicating an unwillingness to have the schizophrenia-vignette person as a neighbor ranges from under a quarter (Brazil) to over three quarters (Bangladesh). Ongoing analyses suggest that this variation is often in evidence across measures, while within-country consistency is high.

Figure 3.

Proportion of Respondents Reporting an Unwillingness to Have the Person in the Schizophrenia Vignette as a Neighbor, Stigma in Global Context–mental Health Study

Note: Arg = Argentina; Bgd = Bangladesh; Bgr = Belgium; Bra = Brazil; Cyp = Cyprus; Deu = Germany; Esp = Spain; Gbr = Great Britain; Hun = Hungary; Isl = Iceland; kor = South korea; Nzl = New Zealand; Phl = Philippines; Usa = United States; Zaf = South Africa.

Speaking to the second issue, researchers used the Eurobarometer 64.4 survey’s attitudes toward “people with psychological or emotional health problems” in 30 countries. Taking a strategy of dividing the samples randomly into halves with group mean centering, “individual” stigmatizing attitudes were found to be “strongly and specifically” associated with “social” stigmatizing attitudes (Mojtabai 2010). A follow-up, focusing on 14 Eurobarometer countries where larger cultural context could be linked to individuals with histories of mental health problems (from the Global Alliance of Mental Illness Advocacy Networks Study; Evans-Lacko et al. 2012), documented a clear association between country levels of stigma and self-stigma. Furthermore, where public levels of comfort with talking to people with mental health problems were higher, consumers reported lower levels of discrimination and a greater sense of empowerment.

Research at these levels is rare and recent. Although they begin to suggest critical macro-micro connections, they support the call for both more research in this vein and further rethinking of stigma research, practice, and policy.

WHAT DO WE THINK? SHAPING NEW ASSUMPTIONS OF STIGMA AND STIGMA CHANGE

Nearly two decades of research and community building efforts have produced a growing, connected network of stigma researchers. As an important source of intellectual ferment, discussions often come back to issues that will play an essential role in future research, program, and policy efforts. They often reflect the spirit of the third CDC question: What do we “think” but do not “know” and, to date, cannot “prove”? Directly connected to fundamental sociological issues and to changing stigma, they require dedicated research efforts aligned with planning initiatives for policy change. And although they neither dismiss nor downplay the salience of issues of neuroscience or clinical interventions, they call for a resource shift to greater fiscal, intellectual, and social capital dedicated to social problems surrounding mental illness.

Issue 1: The Essential Role of Monitoring Stigma at the Global and Individual Levels

Perhaps one of the greatest contributions of the resurgence lay in countering assumptions and unsystematic observations of larger trends in prejudice and discrimination. To push our understanding of the cultural landscape of stigma further and to guide programmatic efforts, there must be a dedicated effort to mark trends.

Kobau et al. (2010) have attempted to do just that. Initial measurement work used the ongoing HealthStyles Survey, which included 11 items on beliefs about “a person with mental illness.” In 2007, 2009, and 2011, the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System included the Mental Illness and Stigma module supported by the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration and the CDC; yet it is not clear that this will be fielded again (see McDaid 2008 on Scotland).

The gap of 45 years between the Star survey and the 1996 GSS represents a lesson not to be repeated. The GSS, Eurobarometer, and Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System need to include a regular and continued focus on mental illness and stigma.

Issue 2: Reconsidering the “Backbone” and “Roots” of Stigma and the Limits of Change

The discussion of monitoring evokes the standard mantra of measuring change over time: “If you want to measure change, don’t change the measure.”8 Marking change requires a pristine focus on comparability, yet the richness of recent stigma research also requires us to step back and ask questions that may also require rethinking.

The robust findings of the resurgence are remarkable given the myriad measures used to tap prejudice and discrimination. Yet these differences leave us asking, What is it about mental illness that is stigmatizing? And what is “underneath” many of the most robust correlates? Typically, the economics of original data collection result in the inclusion of one or two batteries, limiting research that unpacks the first question. While focusing on specific hypotheses (e.g., attribution) or whole systems (e.g., the etiology and effects of stigma model [Martin et al. 2000], the framework integrating normative influences on stigma model [Pescosolido, Martin, et al. 2008]), attempts to get past basic findings have been disappointing. For example, “contact” has been measured in many ways, in many venues, retrospectively and prospectively, and always associated with lower stigma levels (Couture and Penn 2003; Kolodziej and Johnson 1996). Yet attempts to move past very crude notions of having experience oneself, or “knowing someone,” have proven less powerful in unraveling what about contact matters (Alexander and Link 2003; Lee, Farrell, and Link 2004).

Both sets of findings suggest stepping back to consider where we are and what directions may be most productive. What are the mutable roots and potential limits in eliminating prejudice and discrimination? Allport himself was concerned that stereotyping is a special case of ordinary cognitive functioning and therefore not totally alterable (Katz 1991). Considered in light of the “disease like any other” tag line, stigma reduction campaigns have increased literacy with no concomitant decrease in rejection. Thus, although changing “hearts and minds” may represent the “litmus test” to mark the challenge of stigma reduction (Pescosolido et al. 2010), Williams (1965) reminded us that “group discrimination and segregation … are embedded in a consistently supporting social structure” (p. 10), suggesting “the emergence of legal and political struggle” combined with “massive nation-wide social movements” among the stigmatized group.

CONCLUSION

The GSS studies, and the larger body of innovative and rigorous studies that constitute my claim of a resurgence of stigma research, have reconfigured the landscape of science and program development, at least to some extent. Yet fundamental questions, only some of which are elaborated above, are critical in order to continue to shine a harsh light on the social fault lines of a society that produces prejudice and discrimination that translates mental illness stigma into a 15- to 20-year reduction in life expectancy (Piatt, Munetz, and Ritter 2010).

As Goffman (1963) reminded us early on, stigma is fundamentally a social phenomenon rooted in social relationships and shaped by the culture and structure of society. If stigma emanates from social relationships, the solution to understanding and changing must similarly be embedded in changing social relationships and the structures that shape them. Goffman’s central observation provides a springboard for research and a lever for change that has often been in the shadows of stigma research, including the studies reviewed here.

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank members of the Award Committee and the many researchers who have been part of this collaborative research agenda on public stigma. In particular, I would like to thank Bruce Link, who led the initial effort with me to convince the GSS and the MacArthur Foundation to begin monitoring the American public’s understanding of and response to mental health issues. I would also like the thank the core of the research team that has been involved for most of the duration, including Jo Phelan, Jack K. Martin, J. Scott Long, Sigrun Olafsdottir, and Brea Perry. Special thanks to Tait Medina for assistance on the 1996 to 2006 graphics presented here. In addition, a number of others contributed to different projects along the way, including Annie Lang, Peter Jensen, John Monahan, Ann McCranie, Danielle Fettes, Giovani Burgos, Anne Stueve, Michelle Bresnahan, Saeko Kikuzawa, Tom Croghan, Steve Tuch, Keri Lubell, Jane McLeod, David Takeuchi, Terry F. White, Jason Schnittker, Ralph Swindle, Ken Heller, and Molly Thompson. I would like to thank Tom W. Smith, both as one of the principal investigators of the GSS and as former secretariat of the International Social Survey Program, for his invaluable assistance at several key points; Emeline Otey at the NIMH for her continual support of stigma research; Thom Bornemann and Rebecca Palpant at the Carter Center for convening several Stigma Leaders Workshops to push the agenda for change; and Glenn Close and Bring Change 2 Mind for reminding me why we do this research. Support for the research reported here has come from the MacArthur Foundation, the Fog-arty International Center, the National Institute of Mental Health, The Office of Behavior and Social Science Research, Eli Lilly and Company, and Indiana University’s College of Arts and Sciences as well as the Department of Sociology. Finally, I would like to express my deep appreciation to Alejandra Capshew and Mary Hannah, the staff of the Indiana Consortium for Mental Health Services Research, who are the keystone of our work. Any errors contained within are solely my responsibility.

Biography

Bernice Pescosolido is Distinguished and Chancellor’s Professor of Sociology at Indiana University and director of the Indiana Consortium for Mental Health Services Research. Professor Pescosolido received a PhD in sociology from Yale University in 1982. She has focused her research and teaching on social issues in health, illness, and healing. More specifically, her research agenda addresses how social networks connect individuals to their communities and to institutional structures, providing the “wires” through which people’s attitudes and actions are influenced. This agenda encompasses three basic areas: health care services, stigma, and suicide research.

Footnotes

The film was based on San Francisco Chronicle journalist Randy Shilts’s 1987 book of the same name. Shilts was tested for HIV while he was writing the book and died of complications of AIDS in 1994.

The ADS Center, originally the Resource Center to Address Discrimination and Stigma Associated with Mental Illness, was renamed in 2008 as the Resource Center to Promote Acceptance, Dignity, and Social Inclusion with Mental Health. The Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration’s 2006 antistigma campaign, targeted to 18- to 25-year-olds, included three public service announcements, printed materials, and support to states. Proposition 63, in effect January 1, 2005, is a 1 percent surcharge on taxpayers with annual taxable incomes of over $1 million, providing funds to expand county mental health services, including stigma reduction efforts.

The first mention of stigma in reference to mental illness did not come in sociology journals but in the British Medical Journal: “Most mental cases in their early days would benefit by removal from their usual surroundings, but naturally enough the patient objects to being sent to an asylum, as this word is associated in his mind with all that is dreadful. The family objects on the same grounds, as well as on account of the stigma attached to this treatment” (Jordan 1909:351). The first mention of mental illness stigma in a sociology journal came in Social Forces: “Mental Illness is difficult to bear in a family because it is mysterious and not well-understood. It must be admitted that it also involves some stigma or disgrace, though this is unreasonable and should be avoided” (Crispell 1939:76).

The GSS Overseers Board heads up module development. GSS had “space” for four 15-minute modules, two on each sample of the biennial fielding, which are selected on the basis of scientific quality and importance.

Figure 1 reports raw percentage changes and appropriate statistical tests of change over the decade. Conclusions from the raw and adjusted analyses (Pescosolido et al. 2010) show little difference.

This may raise questions of comparability over time. Would Americans in the 1990s embrace notions of “nervous breakdown”? Although Gove (2004) suggested that this remains a way that individuals destigmatize emotional problems rather than the more harsh term mental illness, psychiatry did not. Without using nervous breakdown, comparisons over time would be compromised. Our two-step solution repeated the exact item but was followed up by a second on experiencing “mental health problems.” Of the 26 percent who provided positive responses, most (19 percent) responded to the first.

The 41.9 percent rejecting the “troubled person” as in-law was surprising, as were additional findings (e.g., 10 percent willing to use coercion; Pescosolido, Monahan, et al. 1999). Sociodemographic analyses suggested no systematic groups here.

Attributed to James Davis, GSS founder, quoted by Peter Marsden at the 2012 annual Schuessler Lecture at Indiana University.

This article is a revision of the Leonard I. Pearlin Award Lecture, presented to the Sociology of Mental Health Section at the annual meeting of the American Sociological Association, Las Vegas, Nevada, 2011.

References

- Alexander Laurel A, Link Bruce G. The Impact of Contact on Stigmatizing Attitudes towards People with Mental Illness. Journal of Mental Health. 2003;12(3):271–89. [Google Scholar]

- Allport Gordon E. The Nature of Prejudice. Garden City, NY: Doubleday; 1954. [Google Scholar]

- Angermeyer Matthias C, Daeumer R, Matschinger Herbert. Benefits and Risks of Psychotropic Medication in the Eyes of the General Public: Results of a Survey in the Federal Republic of Germany. Pharmacopsychiatry. 1993;26(4):114–20. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-1014354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Angermeyer Matthias C, Matschinger Herbert. Causal Beliefs and Attitudes to People with Schizophrenia. British Journal of Psychiatry. 2005;186:331–34. doi: 10.1192/bjp.186.4.331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bailey SR. An Exploration of Critical Care Nurses’ and Doctors’ Attitudes towards Psychiatric Patients. Australian Journal of Advanced Nursing. 1998;15(3):8–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins Randall. Is 1980s Sociology in the Doldrums? American Journal of Sociology. 1986;91(6):1336–55. [Google Scholar]

- Corrigan Patrick W, Penn David L. Lessons from Social Psychology on Discrediting Psychiatric Stigma. American Psychologist. 1999;54(9):765–75. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.54.9.765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Couture Shannon, Penn David L. Interpersonal Contact and the Stigma of Mental Illness: A Review of the Literature. Journal of Mental Health. 2003;12(3):291–305. [Google Scholar]

- Crisp Arthur H, Gelder Michael G, Rix Susannah, Meltzer Howard I, Rowlands Olwen J. Stigmatization of People with Mental Illness. British Journal of Psychiatry. 2000;177(1):4–7. doi: 10.1192/bjp.177.1.4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crispell Raymond S. The Bearing of Nervous and Mental Diseases on the Conservation of Marriage and the Family. Social Forces. 1939;18(1):71–76. [Google Scholar]

- Croghan Thomas W, Tomlin Molly, Pescosolido Bernice A, Martin Jack K, Lubell Keri M, Swindle Ralph. Americans’ Knowledge and Attitudes towards and Their Willingness to Use Psychiatric Medications. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease. 2003;191(3):166–74. doi: 10.1097/01.NMD.0000054933.52571.CA. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cumming Elaine, Cumming John. Closed Ranks: An Experiment in Mental Health Education. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 1957. [Google Scholar]

- Dovidio John F, Glick Peter, Rudman Laurie. On the Nature of Prejudice: Fifty Years After Allport. New York: Wiley-Blackwell; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Ellison Christopher G, Vaaler Margaret L, Flannelly Kevin J, Weaver Andrew J. The Clergy as a Source of Mental Health Assistance: What Americans Believe. Review of Religious Research. 2006;48(2):190–211. [Google Scholar]

- Estroff Sue E. Making It Crazy: An Ethnography of Psychiatric Clients in an American Community. Berkeley: University of California Press; 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Evans-Lacko Sara, Brohan Elaine, Mojtabai Ramin, Thornicroft Graham. Association between Public Views of Mental Illness and Self-stigma among Individuals with Mental Illness in 14 European Countries. Psychological Medicine. 2012;42(8):1741–1752. doi: 10.1017/S0033291711002558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fabrega Horatio., Jr The Culture and History of Psychiatric Stigma in Early Modern and Modern Western Societies: A Review of Recent Literature. Comprehensive Psychiatry. 1991;32(2):97–119. doi: 10.1016/0010-440x(91)90002-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goffman Erving. The Presentation of Self in Everyday Life. New York: Anchor; 1959. [Google Scholar]

- Goffman Erving. Asylums: Essays on the Social Situation of Mental Patients and Other Inmates. Garden City, NY: Anchor; 1961. [Google Scholar]

- Goffman Erving. Stigma: Notes on the Management of Spoiled Identity. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall; 1963. [Google Scholar]

- Gove Walter R. The Career of the Mentally Ill: An Integration of Psychiatric, Labeling/Social Construction, and Lay Perspectives. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 2004;45(4):357–75. doi: 10.1177/002214650404500401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gurin Gerald, Veroff Joseph, Feld Sheila. Americans View Their Mental Health. New York: Basic Books; 1960. [Google Scholar]

- Hinshaw Stephen P. The Mark of Shame: Stigma of Mental Illness and an Agenda for Change. Oxford, United Kingdom: Oxford University Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Jordan FW. Receiving Houses for Incipient Mental Disorder. British Medical Journal. 1909;2(2536):351. [Google Scholar]

- Jorm Anthony F, Korten Alisa E, Jacomb Patricia A, Christensen Helen, Rodgers Bryan, Politt Penelope. Mental Health Literacy: A Survey of the Public’s Ability to Recognize Mental Disorders and Beliefs about Treatment. Medical Journal of Australia. 1997;166(4):182–86. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.1997.tb140071.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katz Irwin. Gordon Allport’s ‘The Nature of Prejudice.’. Political Psychology. 1991;12(1):125–157. [Google Scholar]

- Kobau Rosemarie, DiIorio Colleen, Chapman Daniel, Delvecchio Paolo. Attitudes about Mental Illness and its Treatment: Validation of a Generic Scale for Public Health Surveillance of Mental Illness Associated Stigma. Community Mental Health Journal. 2010;46(2):164–76. doi: 10.1007/s10597-009-9191-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohn Melvin L, Williams Robin M. Situational Patterning in Intergroup Relations. American Sociological Review. 1956;21(2):164–74. [Google Scholar]

- Kolodziej Monika E, Johnson Blair T. Interpersonal Contact and Acceptance of Persons with Psychiatric Disorders: A Research Synthesis. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1996;64(4):1387–96. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.64.6.1387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kulka Richard A, Veroff Joseph, Douvan Elizabeth. Social Class and the Use of Professional Help for Personal Problems: 1957 and 1976. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 1979;20(1):2–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee Barrett A, Farrell Chad R, Link Bruce G. Revisiting the Contact Hypothesis: The Case of Public Exposure to Homelessness. American Sociological Review. 2004;69(1):40–63. [Google Scholar]

- Link Bruce G, Castille Dorothy M, Stuber Jennifer. Stigma and Coercion in the Context of Outpatient Treatment for People with Mental Illnesses. Social Science & Medicine. 2008;67(3):409–19. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2008.03.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Link Bruce G, Cullen Francis T, Struening Elmer L, Shrout Patrick E, Dohrenwend Bruce P. A Modified Labeling Theory Approach to Mental Disorders: An Empirical Assessment. American Sociological Review. 1989;54(3):400–23. [Google Scholar]

- Link Bruce G, Phelan Jo C. The Labeling Theory of Mental Disorder (I): The Role of Social Contingencies in the Application of Psychiatric Labels. In: Horwitz AV, Scheid TL, editors. A Handbook for the Study of Mental Health. Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press; 1999. pp. 139–50. [Google Scholar]

- Link Bruce G, Phelan Jo C. Conceptualizing Stigma. Annual Review of Sociology. 2001;27:363–85. [Google Scholar]

- Link Bruce G, Struening Elmer L, Rahav Michael, Phelan Jo C, Nuttbrick Larry. On Stigma and Its Consequences: Evidence from a Longitudinal Study of Men with Dual Diagnoses of Mental Illness and Substance Abuse. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 1997;38(2):177–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Markowitz Fred E. The Effects of Stigma on the Psychological Well-Being and Life Satisfaction of Persons with Mental Illness. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 1998;39(4):335–47. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin Jack K, Pescosolido Bernice A, Olafsdottir Sigrun, McLeod Jane D. The Construction of Fear: Modeling Americans’ Preferences for Social Distance from Children and Adolescents with Mental Health Problems. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 2007;48(1):50–67. doi: 10.1177/002214650704800104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin Jack K, Pescosolido Bernice A, Tuch Steven. Of Fear and Loathing: The Role of Disturbing Behavior, Labels and Causal Attributions in Shaping Public Attitudes toward Persons with Mental Illness. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 2000;41(2):208–33. [Google Scholar]

- McDaid David. Countering the Stigmatisation and Discrimination of People with Mental Health Problems in Europe. London: European Commission; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- McLeod Jane D, Fettes Danielle L, Jensen Peter S, Pescosolido Bernice A, Martin Jack K. Public Knowledge, Beliefs, and Treatment Preferences Concerning Attention-Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder. Psychiatric Services. 2007;58(5):626–31. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.58.5.626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michels Kathleen M, Hofman Karen J, Keusch Gerald T, Hrynkow Sharon H. Stigma and Global Health: Looking Forward. The Lancet. 2006;367(9509):538–39. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)68190-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mirowsky John, Ross Catherine E. Psychiatric Diagnosis as Reified Measurement. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 1989;30(1):11–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mojtabai Ramin. Mental Illness Stigma and Willingness to Seek Mental Health Care in the European Union. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology. 2010;45(7):705–12. doi: 10.1007/s00127-009-0109-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myrdal Gunnar. An American Dilemma: The Negro Problem and Modern Democracy. New York: Harper; 1944. [Google Scholar]

- Nunnally Jim C. Popular Conceptions of Mental Health. New York: Holt, Rhinehart, & Winston; 1961. [Google Scholar]

- Olafsdottir Sigrun. Medicalization and Mental Health: The Critique of Medical Expansion, and a Consideration of How National States, Markets, and Citizens Matter. In: Pilgrim D, Rogers A, Pescosolido BA, editors. The Sage Handbook of Mental Health and Illness. London: Sage Ltd; 2011. pp. 239–60. [Google Scholar]

- Olafsdottir Sigrun, Pescosolido Bernice A. Drawing the Line: The Cultural Cartography of Utilization Recommendations for Mental Health Problems. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 2009;50(2):228–44. doi: 10.1177/002214650905000208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olafsdottir Sigrun, Pescosolido Bernice A. Constructing Illness: How the Public in Eight Western Nations Respond to a Clinical Description of ‘Schizophrenia.’. Social Science & Medicine. 2011;73(6):929–38. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.06.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Payton Andrew R, Thoits Peggy A. Medicalization, Direct-to-Consumer Advertising, and Mental Illness Stigma. Society and Mental Health. 2011;1(1):55–70. [Google Scholar]

- Perry Brea L, Pescosolido Bernice A. Children, Culture, and Mental Illness: Public Knowledge and Stigma toward Childhood Problems. In: Pilgrim D, Rogers A, Pescosolido BA, editors. The Sage Handbook of Mental Health and Illness. London: Sage Ltd; 2011. pp. 202–17. [Google Scholar]

- Perry Brea L, Pescosolido Bernice A, Martin Jack K, McLeod Jane D, Jensen Peter S. Comparison of Public Attributions, Attitudes, and Stigma in Regard to Depression among Children and Adults. Psychiatric Services. 2007;58(5):632–35. doi: 10.1176/ps.2007.58.5.632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pescosolido Bernice A. Culture, Children, and Mental Health Treatment: Special Section on the National Stigma Study–Children. Psychiatric Services. 2007;58(5):611–12. doi: 10.1176/ps.2007.58.5.611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pescosolido Bernice A. Response to Torrey Letter. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2011;168(3):325–26. [Google Scholar]

- Pescosolido Bernice A, Boyer Carol A, Lubell Keri M. The Social Dynamics of Responding to Mental Health Problems: Past, Present, and Future Challenges to Understanding Individuals’ Use of Services. In: Aneshensel CS, Phelan JC, editors. Handbook of the Sociology of Mental Health. New York: Plenum; 1999. pp. 441–60. [Google Scholar]

- Pescosolido Bernice A, Fettes Danielle L, Martin Jack K, Monahan John, McLeod Jane D. Perceived Dangerousness of Children with Mental Health Problems and Support for Coerced Treatment. Psychiatric Services. 2007;58(5):1–7. doi: 10.1176/ps.2007.58.5.619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pescosolido Bernice A, Jensen Peter, Martin Jack K, Perry Brea L, Olafsdottir Sigrun, Fettes Danielle L. Public Knowledge and Assessment of Child Mental Health Problems: Findings from the National Stigma Study–Children. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2008;47(3):339–49. doi: 10.1097/CHI.0b013e318160e3a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pescosolido Bernice A, Martin Jack K. Stigma and the Sociological Enterprise. In: Avison WR, McLeod JD, Pescosolido BA, editors. Mental Health, Social Mirror. New York: Springer; 2007. pp. 307–28. [Google Scholar]

- Pescosolido Bernice A, Martin Jack K, Lang Annie, Olafsdottir Sigrun. Rethinking Theoretical Approaches to Stigma: A Framework Integrating Normative Influences on Stigma (FINIS) Social Science & Medicine. 2008;67(3):431–40. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2008.03.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pescosolido Bernice A, Martin Jack K, Scott Long J, Medina Tait, Phelan Jo C, Link Bruce G. ‘A Disease Like Any Other?’ A Decade of Change in Public Reactions to Schizophrenia, Depression and Alcohol Dependence. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2010;167(11):1321–30. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2010.09121743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pescosolido Bernice A, McLeod Jane D, Avison William R. Through the Looking Glass: The Fortunes of the Sociology of Mental Health. In: Avison WR, McLeod JD, Pescosolido BA, editors. Mental Health, Social Mirror. New York: Springer; 2007. pp. 3–32. [Google Scholar]

- Pescosolido Bernice A, Monahan John, Link Bruce G, Stueve Ann, Kikuzawa Saeko. The Public’s View of the Competence, Dangerousness, and Need for Legal Coercion of Persons with Mental Health Problems. American Journal of Public Health. 1999;89(9):1339–45. doi: 10.2105/ajph.89.9.1339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pescosolido Bernice A, Olafsdottir Sigrun. The Cultural Turn in Sociology: Can It Help Us Resolve an Age-Old Problem in Understanding Decision-Making for Health Care? Sociological Forum. 2010;25(4):655–76. doi: 10.1111/j.1573-7861.2010.01206.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pescosolido Bernice A, Olafsdottir Sigrun, Martin Jack K, Scott Long J. Cross-Cultural Aspects of the Stigma of Mental Illness. In: Arboleda-Florez J, Sartorius N, editors. Understanding the Stigma of Mental Illness: Theory and Interventions. London: Wiley Ltd; 2008. 000–000. [Google Scholar]

- Pescosolido Bernice A, Perry Brea L, Martin Jack K, McLeod Jane D, Jensen Peter S. Stigmatizing Attitudes and Beliefs about Treatment and Psychiatric Medications for Children with Mental Illness. Psychiatric Services. 2007;58(5):613–18. doi: 10.1176/ps.2007.58.5.613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pescosolido Bernice A, Wright Eric R, Alegria Margarita, Vera Mildred. Social Networks and Patterns of Use among the Poor with Mental Health Problems in Puerto Rico. Medical Care. 1998;36(7):1057–72. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199807000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pettigrew Thomas F, Tropp Linda R. Does Intergroup Contact Reduce Prejudice? Recent Meta-Analytic Findings. In: Oskamp S, editor. Reducing Prejudice and Discrimination: Social Psychological Perspectives. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum; 2000. pp. 93–114. [Google Scholar]

- Phelan Jo C. Geneticization of Deviant Behavior and Consequences for Stigma: The Case of Mental Illness. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 2005;46(4):307–22. doi: 10.1177/002214650504600401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phelan Jo C, Link Bruce G, Stueve Ann, Pescosolido Bernice A. Public Conceptions of Mental Illness in 1950 and 1996: What Is Mental Illness and Is It to Be Feared? Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 2000;41(2):188–207. [Google Scholar]

- Phelan Jo C, Yang Lawrence Hsin, Cruz-Rojas Rosangely. Effects of Attributing Serious Mental Illnesses to Genetic Causes on Orientations to Treatment. Psychiatric Services. 2006;57(3):382–87. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.57.3.382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piatt Elizabeth E, Munetz Mark R, Ritter Christian. An Examination of Premature Mortality among Decedents with Serious Mental Illness and Those in the General Population. Psychiatric Services. 2010;61(7):663–68. doi: 10.1176/ps.2010.61.7.663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pilgrim David, Rogers Anne. Danger and Diagnosed Mental Disorder. In: Pilgrim D, Rogers A, Pescosolido BA, editors. The Sage Handbook of Mental Health and Illness. London: Sage Ltd; 2011. pp. 261–84. [Google Scholar]

- President’s New Freedom Commission on Mental Health. Achieving the Promise: Transforming Mental Health Care in America. Bethesda, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenfield Sarah. Labeling Mental Illness: The Effects of Received Services and Perceived Stigma on Life Satisfaction. American Sociological Review. 1997;62(4):660–72. [Google Scholar]

- Sartorius Norman. Fighting Schizophrenia and Its Stigma. A New World Psychiatric Association Educational Programme. British Journal of Psychiatry. 1997;170(4):297. doi: 10.1192/bjp.170.4.297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scambler Graham. Stigma and Mental Disorder. In: Pilgrim D, Rogers A, Pescosolido BA, editors. The Sage Handbook of Mental Health and Illness. London: Sage Ltd; 2011. pp. 218–38. [Google Scholar]

- Scheff Thomas J. Being Mentally Ill: A Sociological Theory. Chicago: Aldine; 1966. [Google Scholar]

- Schnittker Jason. Gender and Reactions to Psychological Problems: An Examination of Social Tolerance and Perceived Dangerousness. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 2000;41(2):224–40. [Google Scholar]

- Schnittker Jason. Misgivings of Medicine? African Americans’ Skepticism of Psychiatric Medication. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 2003;44(4):506–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]