Abstract

Introduction

Sinus arrest, atrio-ventricular block, supraventricular, and ventricular arrhythmias have been reported in patients with sleep apnea syndrome. The arrhythmias usually occur during sleep and contribute to the cardiovascular morbidity and mortality, and the treatment of sleep apnea usually results in the resolution of the brady- arrhythmias. Weight loss, continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP), oral appliances, and upper airway surgery are the recommended treatments, however, compliance and efficacy are issues.

Case presentation

A 58-year-old Arab man presented with recurrent presyncope. He was subsequently diagnosed with sleep apnea associated with frequent and significant sinus pauses. He presented a treatment challenge because he refused continuous positive airway pressure and pacemaker, however, he was successfully treated with theophylline.

Conclusion

Frequent and significant sinus pause associated with sleep apnea was successfully treated with theophylline in our patient when the standard treatment of care was refused.

Keywords: Bradycardia, Sinus arrest, Sleep apnea, Theophylline

Introduction

Sleep apnea-associated bradyarrhythmias contribute to the cardiovascular mortality and morbidity of sleep apnea [1-4] and treatment of sleep apnea usually results in resolution of bradyarrhythmias [3]. To date, weight loss, continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP), oral appliances, and upper airway surgery are the recommended treatments; however, compliance and efficacy are issues [5,6]. Our patient presented a treatment challenge because he had significant sinus pauses associated with sleep apnea, but he refused recommended treatment. Theophylline, used to treat brady-arrhythmia in different settings, was introduced as an alternative treatment option and was successful in treating our patient.

Case presentation

A 58-year-old Arab man was referred to our electrophysiology clinic with monthly episodes of presyncope for the last 3 months. Despite two episodes of presyncope per year for 3 years, he had not sought medical advice. He had multiple comorbidities including coronary artery disease status post coronary artery bypass surgery (CABG), type 2 diabetes mellitus, dyslipidemia, and class III obesity (body mass index 41) with a neck circumference of 45cm and modified Mallampati score of 4.

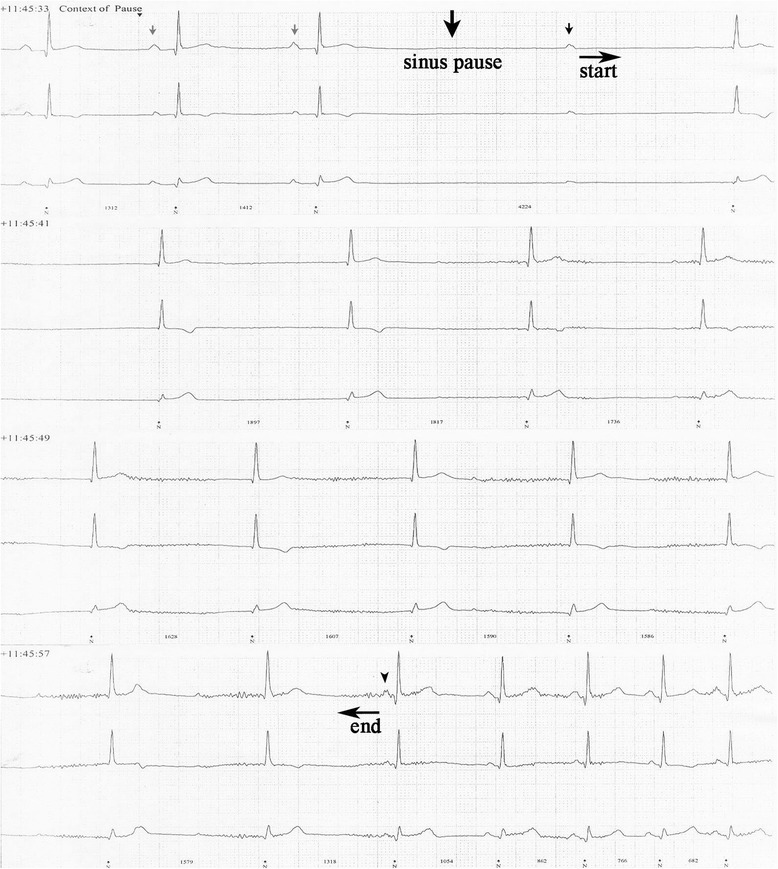

After his CABG, aspirin, atorvastatin, and metformin were restarted, with the addition of metoprolol tartrate 25mg twice daily. More frequent episodes of presyncope occurred. An electrocardiogram revealed normal sinus rhythm with normal PR, QRS and QTc intervals. Transthoracic echocardiography demonstrated a normal left ventricular systolic function and 24-hour ambulatory Holter monitoring recorded multiple sinus pauses occurring from 11:22 p.m. until 11:46 a.m. with a maximum pause of 22 seconds occurring at 11:45:33 a.m. (see Figure 1). During this observation, there were no episodes of presyncope.

Figure 1.

Holter recording displaying a prolonged sinus pause. A sample from the Holter recording displaying a non-conducted P-wave (small black arrow) preceded by a sinus pause of 2.7 seconds (large black arrow) and followed by sinus arrest of 22 seconds with junctional escape beats (between the horizontal start and end arrows). The gray arrows point to sinus bradycardia and black arrowhead points to the first P-wave, after the return of sinus rhythm. Holter revealing a non-conducted P-wave (small black arrow) followed by sinus arrest (horizontal arrows).

He was admitted to our hospital for further workup. Despite discontinuation of metoprolol for 1 week, his telemetry revealed multiple episodes of sinus pause, observed during daytime sleepiness or snoring episodes. Obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) was suspected and a sleep study demonstrated both central and OSA: Epworth score 7, sleep latency of 17 minutes, Apnea–Hypopnea Index (AHI) of 98/hour, arousal index of 49/hour and lowest oxygen saturation at 78% on room air (Table 1).

Table 1.

Symptoms reported, Holter monitor, theophylline levels and polysomnography results at presentation and during follow up

| Symptoms | Weight (kg) | 24-hour Holter monitor | Theophylline level * | Polysomnography | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Max sinus pause (seconds) | Total number of sinus pauses | Min/max/Average HR (beats/minute) | |||||

| Prior to presentation (2008 until 2011) | Presyncope twice a year for 3 years | 115 | – | – | – | Not on treatment | – |

| At presentation (September 2011) | Presyncope once a month for 3 months | 119 | 22 | 71 | 49/119/85 | Not on treatment | Epworth score 7 |

| Sleep latency of 17 minutes | |||||||

| AHI of 98/hour | |||||||

| Arousal index of 49/hour | |||||||

| Lowest oxygen saturation at 78% on room air | |||||||

| 5-month follow up | None | 120 | 6 | 18 | 61/125/93 | 11.11 | Not done |

| 6-month follow up | None | 122 | 5 | 5 | 68/124/94 | 13.0 | Not done |

| 7-month follow up | None | 126 | None | None | 71/128/92 | 14.4 | Epworth score of 11 |

| Sleep latency of 28 minutes | |||||||

| AHI of 96/hour | |||||||

| Arousal index of 43/hour | |||||||

| Lowest oxygen saturation at 78% on room air | |||||||

| 14-month follow up | None | 123 | None | None | 69/123/90 | 11.4 | Not done |

| 19-month follow up | None | 129 | 2.9 | 3 | 67/115/82 | 14.6 | Epworth score of 11 |

| Sleep latency of 48.5 minutes | |||||||

| AHI of 83/hour | |||||||

| Arousal index of 42.8/hour | |||||||

| Lowest oxygen saturation at 75% on room air | |||||||

| 29-month follow up | None | 130 | None | None | 65/110/81 | Not done | Not done |

AHI = Apnea–Hypopnea Index; HR = Heart rate; Max = Maximum; Min = Minimum.

*Therapeutic level is between 10 and 20mcg/mL in plasma [4].

Overnight CPAP was started and the telemetry showed sinus bradycardia with a minimum heart rate of 30 beats per minute with infrequent pauses of less than 3 seconds. However he refused to continue to use the CPAP upon discharge. In addition, he was offered a pacemaker and he refused. A trial of theophylline 200mg twice daily was initiated and he was discharged from our hospital and encouraged to initiate a weight reduction program.

At follow up, he had no further episode of presyncope with infrequent short or no pauses at therapeutic theophylline levels (Table 1). A follow-up sleep study revealed improvement in the central element of his sleep apnea, however, his AHI did not significantly improve; such results are expected with theophylline therapy (Table 1).

Discussion

Sleep apnea syndrome has been associated with cardiovascular complications including hypertension [1], heart failure [2] and cardiac arrhythmia [3]. Observational studies have shown that treating sleep apnea syndrome can decrease blood pressure [1], reduce cardiac arrhythmia [3] and decrease cardiovascular mortality [4]. Noninvasive positive pressure ventilation effectively decreases the incidence of sleep apnea-associated arrhythmia [3]; however, not all patients can tolerate it and compliance is an issue [5]. We report the case of a patient who presented with presyncope most likely secondary to sleep apnea-induced brady-arrhythmia. He was started on beta-blockers after his CABG, which could have made his brady-arrhythmia worse and contributed to increasing presyncope. However, while he was an in-patient and off his metoprolol he continued to have significant sinus pause. He did not tolerate CPAP and refused a pacemaker so, as a last resort, theophylline treatment was started and he reported complete resolution of his symptoms. A Holter monitor documented a decrease in both the frequency and duration of sinus pauses. We initiated theophylline based on its effectiveness in treating brady-arrhythmia in the setting of post-cardiac transplant [6] and spinal cord injury [7]. The mechanism of brady-arrhythmia in sleep apnea syndrome is hypothesized to be due to the activation of the diving reflex by hypoxemia and apnea, with reflex activation of the cardiac vagal nerve. This induces severe nocturnal bradyarrhythmias, especially during rapid eye movement sleep [8]. Theophylline is a nonselective phosphodiesterase inhibitor that also competitively blocks adenosine receptors resulting in central nervous system and cardiovascular stimulation. Theophylline also increases the respiratory drive and it has been used in patients with central sleep apnea due to left ventricular dysfunction before CPAP and is still recommended in patients who cannot tolerate CPAP [9]. For OSA, theophylline has been shown to mildly reduce obstructive events but is associated with sleep disruption and therefore it is not recommended [9]. The limitations and side effects of theophylline result from its narrow therapeutic index, traditionally between 10 and 20mcg/mL [4] in plasma. Theophylline is metabolized in the liver through the cytochrome P450 system and consequently is implicated in several drug interactions with commonly prescribed drugs, which may increase serum concentrations of theophylline [10].

Conclusions

We report a case of treating sleep apnea-induced brady-arrhythmia with theophylline when standard treatment of care was refused. Further studies are needed to determine the safety and efficacy of theophylline for treating sleep apnea-induced bradyarrhythmias to ensure the benefits outweigh the risks.

Consent

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report and any accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the Editor-in-Chief of this journal.

Acknowledgement

The lead author would like to acknowledge Dr. James Stewart and Dr. Ciaran M. Dixon for their assistance in proofreading the manuscript.

The work was conducted in the Section of Adult Cardiology, Cardiovascular Department, King Faisal Specialist Hospital & Research Center-Jeddah, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia.

Abbreviations

- AHI

Apnea–Hypopnea Index

- CABG

Coronary artery bypass surgery

- CPAP

Continuous positive airway pressure

- OSA

Obstructive sleep apnea

Footnotes

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

AD was the major contributor and provided care to the patient. AD also conceived the case report, collected information and wrote the manuscript. SO, SMAF AAAA and AL contributed in writing the manuscript and developing the table and figure. WA assisted with data collection. FA contributed in the preparation, editing and revision of the manuscript. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Contributor Information

Amin Daoulah, Email: amindaoulah@yahoo.com.

Sara Ocheltree, Email: dr.sara.ocheltree@gmail.com.

Salem M Al-Faifi, Email: salemalfaifi@hotmail.com.

Waleed Ahmed, Email: waleedamasaib@hotmail.com.

Alawi A Alsheikh-Ali, Email: alsheikhali@gmail.com.

Farhan Asrar, Email: farhan.asrar@medportal.ca.

Amir Lotfi, Email: amir.lotfi@tufts.edu.

References

- 1.Dhillon S, Chung S, Fargher T, Huterer N, Shapiro C. Sleep apnea, hypertension, and the effects of continuous positive airway pressure. Am J Hypertens. 2005;18:594–600. doi: 10.1016/j.amjhyper.2004.11.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Naughton M. The link between obstructive sleep apnea and heart failure: underappreciated opportunity for treatment. Curr Cardiol Rep. 2005;7:211–5. doi: 10.1007/s11886-005-0079-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Simantirakis EN, Schiza SI, Marketou ME, Chrysostomakis SI, Chlouverakis GI, Klapsinos NC, et al. Severe bradyarrhythmias in patients with sleep apnoea: the effect of continuous positive airway pressure treatment: a long-term evaluation using an insertable loop recorder. Eur Heart J. 2004;25:1070–6. doi: 10.1016/j.ehj.2004.04.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Buchner NJ, Sanner BM, Borgel J, Rump LC. Continuous positive airway pressure treatment of mild to moderate obstructive sleep apnea reduces cardiovascular risk. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2007;176:1274–80. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200611-1588OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zozula R, Rosen R. Compliance with continuous positive airway pressure therapy: assessing and improving treatment outcomes. Curr Opin Pulm Med. 2001;7:391–8. doi: 10.1097/00063198-200111000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Qaseem A, Holty JEC, Owens DK, Dallas P, Starkey M, Shekelle P, et al. A clinical practice guideline from the American College of Physicians. Ann Intern Med. 2013;159:471–83. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-159-7-201310010-00704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bertolet BD, Eagle DA, Conti JB, Mills RM, Belardinelli L. Bradycardia after heart transplantation: reversal with theophylline. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1996;28:396–9. doi: 10.1016/0735-1097(96)00162-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sakamoto T, Sadanaga T, Okazaki T. Sequential use of aminophylline and theophylline for the treatment of atropine-resistant bradycardia after spinal cord injury: a case report. J Cardiol. 2007;49:91–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Javaheri S, Parker TJ, Wexler L, Liming JD, Lindower P, Roselle GA. Effect of theophylline on sleep-disordered breathing in heart failure. N Engl J Med. 1996;335:562–7. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199608223350805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Giembycz MA, Corrigan CJ, Seybold J, Newton R, Barnes PJ. Identification of cyclic AMP phosphodiesterases 3, 4 and 7 in human CD41 and CD81 T-lymphocytes: role in regulating proliferation and the biosynthesis of interleukin-2. Br J Pharmacol. 1996;118:1945–58. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1996.tb15629.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]