Abstract

Objective

To determine the incidence trend of 25-hydroxyvitamin D [25(OH)D] values >50 ng/mL and associated toxicity.

Patients and Methods

We conducted a retrospective, population-based study in Olmsted County, MN, from January 1, 2002 through December 31, 2011 (10 years) using the Rochester Epidemiology Project. Individuals were eligible if they resided in Olmsted County, MN, during the study period and had a measured 25(OH)D value >50 ng/mL (>125 nmol/L). The date of the first 25(OH)D value >50 ng/mL was considered the index date for incidence determination. Hypercalcemia, the primary vitamin D toxicity, was considered potentially associated with the 25(OH)D concentration if measured within 3 months of the 25(OH)D measurement, and such cases had medical record review.

Results

Of 20,308 total 25(OH)D measurements, 1714 (8.4%), 123 (0.6%), and 37 (0.2%) unique persons had 25(OH)D values >50, ≥80, and ≥100 ng/mL, respectively. The age- and sex-adjusted incidence of 25(OH)D values >50 ng/mL increased from 9 to 233 per 100,000 person-years from 2002 to 2011 (P<.001), respectively, and was greatest in persons of age ≥65 years (P<.001) and in females (P<.001). Serum 25(OH)D values were not significantly related with serum calcium values or with the risk of hypercalcemia. Medical record review identified four cases (0.2%) where 25(OH)D values >50 ng/mL were associated temporally with hypercalcemia, but only one had clinical toxicity associated with the highest observed 25(OH)D value of 364 ng/mL.

Conclusion

The incidence of 25(OH)D values >50 ng/mL increased significantly between 2002 and 2011, without a corresponding increase in acute clinical toxicity.

Introduction

Due to increasing awareness of vitamin D deficiency in recent years,1 vitamin D supplement use by the population has increased,2 and the prescription of high dose vitamin D has gained traction for the treatment of vitamin D deficiency.3-5 Increasing utilization of vitamin D supplementation may be associated with increasing risk of vitamin D toxicity, primarily hypercalcemia.

Existing data on vitamin D toxicity have been drawn almost exclusively from individual case reports and small case series. To date, the population-based incidence of hypervitaminosis D and associated toxicity has not been directly studied using serum concentrations of 25(OH)D, the accepted measure of vitamin D status. The 25(OH)D concentrations at which toxicity is evident have proven difficult to determine.6,7 The majority of acute vitamin D intoxication reports involve serum 25(OH)D values above 140 ng/mL,8 with the primary clinical manifestation being hypercalcemia and its associated symptoms.7-11 In a vitamin D risk assessment, Hathcock et al. concluded that a reasonable and safe Tolerable Upper Intake Level (UL) should be 10,000 IU vitamin D/day, which corresponds to a serum 25(OH)D concentration of approximately 100 ng/mL.12 In 2011 the Endocrine Society incorporated these levels into their guidelines for the treatment and prevention of vitamin D deficiency.13 Earlier the same year, the Institute of Medicine (IOM) had released their recommendations in the Dietary Reference Intakes for Calcium and Vitamin D. The IOM committee reviewed several studies which showed that chronic ingestion of excess vitamin D resulting in 25(OH)D values above 30-60 ng/mL may be associated with an increased risk of all-cause mortality, cardiovascular disease, fractures and falls.7 Using a cautious approach to the evidence, the committee recommended a UL of 4,000 IU, corresponding to a serum 25(OH)D concentration of 50 ng/mL.

Our objectives were to determine the incidence trend of 25(OH)D values >50 ng/mL from 2002 to 2011 and their association with hypercalcemia. We hypothesized that, due to increased awareness of vitamin D deficiency and supplementation with vitamin D during this interval, the incidence of 25(OH)D values >50 ng/mL and vitamin D toxicity, as evidenced by hypercalcemia, have increased.

Methods

Olmsted County and the Rochester Epidemiology Project

Data from the Rochester Epidemiology Project (REP) was used to determine the incidence of 25(OH)D values >50 ng/mL in the 10-year period from January 1, 2002 to December 31, 2011. The REP database is a rare example of a population-based medical record linkage system that includes over fifty years of health care utilization, diagnostic and laboratory data from virtually all medical care providers within Olmsted County, Minnesota, covering 98% of all health care services provided for Olmsted County residents.14 The county is served by two large integrated health systems, the Mayo Clinic and the Olmsted Medical Center, including primary through tertiary services, outpatient and hospital care.15,16 Over 95% of the Olmsted County population have not refused the medical records research authorization required by Minnesota law thus allowing their records to be used for research.17,18

Olmsted County, MN is located in the Upper-Midwestern United States (44° north latitude) and has limited sun exposure for residents in winter months. The population of Olmsted County increased from 135,897 to 148,700 from 2002 to 2011. In the 2000 and 2010 censuses, the proportions of Olmsted County residents classified as white, black, Asian and Hispanic were 90% and 86%, 2.7% and 4.8%, 4.3% and 5.5%, and 2.4% and 4.2%, respectively. The proportions of males were 49% and 48%, and of individuals aged 65 years and older 11% and 13%, respectively. Compared with the entire U.S. 2010 population, the county is less ethnically diverse (72% versus 86% white), more educated (85% versus 94% high school graduates) and wealthier ($51,914 versus $64,090 median household income). However, the characteristics of the population are very similar to the overall population of the upper Midwest.19

Operational Definitions

The date of the first 25(OH)D value >50 ng/mL for each individual was considered the index date for incidence determination, and the 25(OH)D value on the index date was used for further analysis. A 25(OH)D threshold of 50 ng/mL was chosen based on the 2011 IOM committee’s recommendation of 50 ng/mL as a safe upper 25(OH)D level.7

Hypercalcemia was defined as serum total calcium or ionized calcium concentration greater than the laboratory upper limit of normal for gender and age (total calcium >10.1 mg/dL or ionized calcium >5.7 mg/dL in adults >21 years of age). Calcium reference ranges for all age groups are included in Table 1. Hypercalcemia was considered potentially associated with 25(OH)D if measured within three months before or after the index date. Based on medical record review, hypercalcemia was attributed to vitamin D when a temporal rise in calcium concentration was associated with the 25(OH)D value, with resolution of hypercalcemia after cessation of vitamin D supplementation, in the absence of another clinical cause of the hypercalcemia.

Table 1.

Characteristics of subjects with serum 25(OH)D values >50 ng/mL.

| Characteristic | Subjects with 25(OH)D >50 ng/mL (N=1714) |

|---|---|

| Age distribution, No. (%) | |

| 0-18 | 65/1714 (4) |

| 19-49 | 472/1714 (28) |

| 50-64 | 548/1714 (32) |

| 65-97 | 629/1714 (37) |

| Sex, No. (%) | |

| Male | 332/1714 (19) |

| Female | 1382/1714 (81) |

| Race, No. (%) | |

| White | 1601/1714 (93) |

| Black | 32/1714 (1.9) |

| Asian | 36/1714 (2.1) |

| Other or unknown | 45/1714 (2.6) |

| Serum 25(OH)D, No. subjects (% of total tests, n=20308) | |

| 25(OH)D >50 ng/mLa | 1714/20308 (8.4) |

| Female | 1382/20308 (6.8) |

| Male | 332/20308 (1.6) |

| 25(OH)D ≥80 ng/mL | 123/20308 (0.6) |

| Female | 101/20308 (0.5) |

| Male | 22/20308 (0.1) |

| 25(OH)D ≥100 ng/mL | 37/20308 (0.18) |

| Female | 30/20308 (0.15) |

| Male | 7/20308 (0.03) |

| Seasonal distribution, No. (%) | |

| May-October | 976/1714 (57) |

| November-April | 738/1714 (43) |

| Serum calcium in subjects with 25(OH)D >50 ng/mL (N=1714) | |

| Calcium measured within 3 months of index date, No. (%) | 1070/1714 (62) |

| Hypercalcemia,b No. (% subjects with calcium measurement) | 165/1070 (15) |

| Serum calcium in subjects with 25(OH)D 51-79 ng/mL (n=1591) | |

| Calcium measured within 3 months of index date, No. (%) | 988/1591 (62) |

| Hypercalcemia, No. (% of subjects with calcium measurement) | 151/988 (15) |

| Serum calcium in cohort with 25(OH)D 80-99 ng/mL (n=86) | |

| Calcium measured within 3 months of index date, No. (%) | 56/86 (65) |

| Hypercalcemia, No. (% of those with calcium measurement) | 9/56 (16) |

| Calcium in cohort with 25(OH)D ≥100 ng/mL (n=37) | |

| Calcium measured within 3 months of index date, No. (%) | 26/37 (70) |

| Hypercalcemia, No. (% of those with calcium measurement) | 5/26 (19) |

| Renal failure (creatinine >2 mg/dLc), No. (%) | 69/1714 (4) |

To convert 25(OH)D to nmol/L, multiply values by 2.496.

Hypercalcemia defined in mg/dL units by gender and age group based on reference values from Mayo Medical Laboratory. To convert either total or ionized calcium to mmol/L, multiply values by 0.25. Males, serum total calcium: >10.1 for ages >21, >10.3 for ages 19-21, >10.4 for ages 17-18, >10.5 for ages 15-16, >10.6 for ages 1-14. Males, serum ionized calcium: >5.7 for ages >19, >5.9 for ages 1-19. Females, serum total calcium: >10.1 for ages >18, >10.3 for ages 15-18, >10.4 for ages 12-14, >10.6 for ages 1-11. Females, serum ionized calcium: >5.7 for ages >17, >5.9 for ages 1-17.

To convert creatinine to μmol/L, multiply value by 88.4.

Subjects

The institutional review boards of Mayo Clinic and Olmsted Medical Center approved the study. Individuals of all ages were eligible for study if they resided in Olmsted County, MN, anytime during the 10-year interval from January 1, 2002, through December 31, 2011, had not refused research authorization, and had a measured 25(OH)D value >50 ng/mL during their Olmsted County residency.

We reviewed the medical records and laboratory data of subjects who had both 25(OH)D values >50 ng/mL and hypercalcemia within three months of the index date to determine if the hypercalcemia could be attributed to vitamin D or another cause as defined above. Information abstracted from the medical record included age, gender, race, duration and dosage of vitamin D and calcium supplement use, other medical diagnoses, medications, laboratory values, and reported symptoms.

Laboratory Methods

All 25(OH)D tests ordered in Olmsted County were sent for measurement at the Mayo Clinic Laboratory during the study interval. Prior to November 2, 2004, 25(OH)D was measured by radioimmunoassay (DiaSorin®, Stillwater, MN) with an inter-assay coefficient of variation of 12-14%. After November 2, 2004, 25(OH)D was measured by isotope-dilution liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) with an inter-assay coefficient of variation of 3.7-11%. Internal validation studies at Mayo Clinic demonstrated that the two methods were comparable in their measurement of the true concentration of 25(OH)D. (Data was obtained from personal oral and written communication with Ravinder Singh, PhD, Department of Laboratory Medicine and Pathology, Mayo Clinic, on January 22, 2014.)

Statistical Analysis

Annual incidence rates for each sex and age group were calculated by dividing the number of cases with 25(OH)D values >50 ng/mL by REP census population estimates. The REP census data provide a validated, virtually complete enumeration of the Olmsted County population at any point in time.19,20 Estimates from the state of Minnesota State Demographic Center were used to aid with linear interpolation between census years. Incidence rates per 100,000 person-years were age- and sex-adjusted to the population structure of the 2010 U.S. total population to improve generalization to the entire U.S. population.

The relation of incidence rates to age, gender and time of diagnosis was accessed by fitting generalized linear models assuming a Poisson error structure with a log-link function, consistent with a log-linear model. All statistical analyses were performed by SAS version 9.3 (SAS Institute Inc, Cary, North Carolina). P-values <.05 were considered statistically significant. Bivariate and multivariate analyses, including adjustments for age, year, gender, and population, were performed to assess for the association between 25(OH)D values >50 ng/mL and hypercalcemia.

Results

A total of 20,308 25(OH)D tests were performed on Olmsted County residents between January 2002 and December 2011. Of these, 1885 (9.3%) unique persons had a 25(OH)D value >50 ng/mL, of which 1714 (91%) had research authorization allowing record abstraction. In these 1714 subjects, 123 (0.6%) and 37 (0.2%) had 25(OH)D concentrations ≥80 and ≥100 ng/mL, respectively (Table 1). The 25(OH)D values ranged from 51 to 218 ng/mL, with a median value of 57 ng/mL and one outlier at 364 ng/mL. Subjects with 25(OH)D values >50 ng/mL were predominantly female (81%), aged ≥50 years (69%), and white (93%).

In a seasonal analysis, 976 instances of individuals with 25(OH)D values >50 ng/mL (57%) were identified in May – Oct and 738 (43%) in Nov – Apr (P<.001) (Table 1). The mean 25(OH)D concentration was greater in subjects detected in winter (62.2 ng/mL with outlier excluded) than in summer (60.6 ng/mL; P=.03). The median (57 ng/mL) was the same in both groups. There were no significant relationships of 25(OH)D ≥80 ng/mL and ≥100 ng/mL with season.

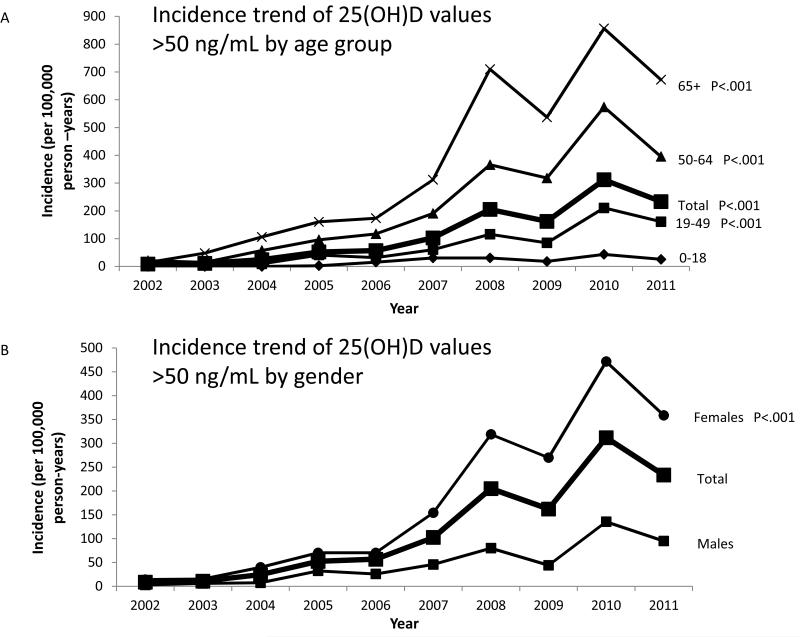

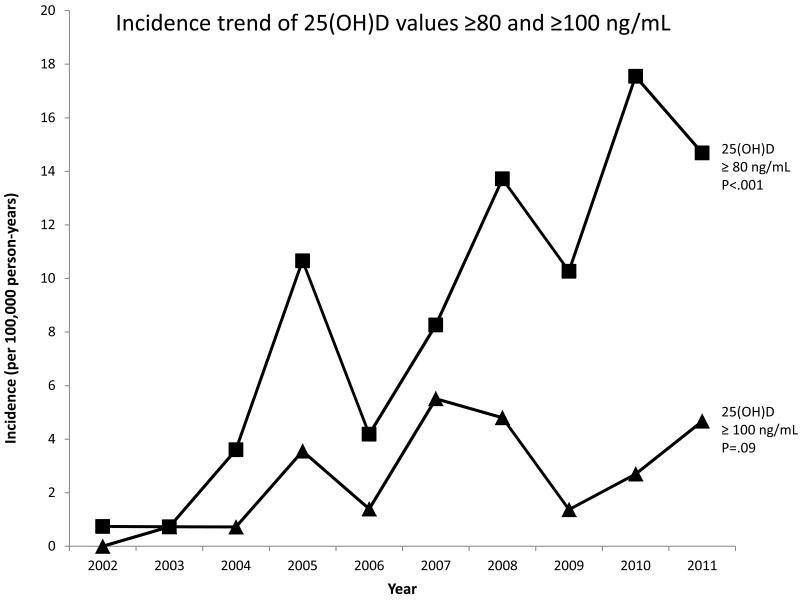

The age- and sex-adjusted incidence of 25(OH)D values >50 ng/mL increased 26-fold from 9 to 233 per 100,000 person-years from 2002 to 2011 (P<.001) (Figure 1). The rise was greatest in females (14 to 358 per 100,000, P<.001) and in persons aged 65 years and older (14 to 672 per 100,000, P<.001). The incidence also increased significantly for subjects with 25(OH)D values ≥80 ng/mL (P<.001), but not for subjects with values ≥100 ng/mL (P=.09) (Figure 2). The annual number of 25(OH)D tests obtained from 2002 to 2011 also increased. After adjustment for the increase in vitamin D testing in a multivariate model, the increase in incidence of 25(OH)D values >50 ng/mL remained significant (P<.001).

Figure 1.

Age- and sex-adjusted incidence trend (per 100,000 person-years) of 25(OH)D values >50 ng/mL from 2002 through 2011. Displayed according to (A) age group (0-18 group is the reference for P-values) and (B) sex (males are the reference for P-values).

Figure 2.

Age- and sex-adjusted incidence trend (per 100,000 person-years) of elevated vitamin D levels from 2002 to 2011 in Olmsted County, MN for individuals with 25(OH)D values ≥80 and ≥100 ng/mL. P-values represent the significance of the trend.

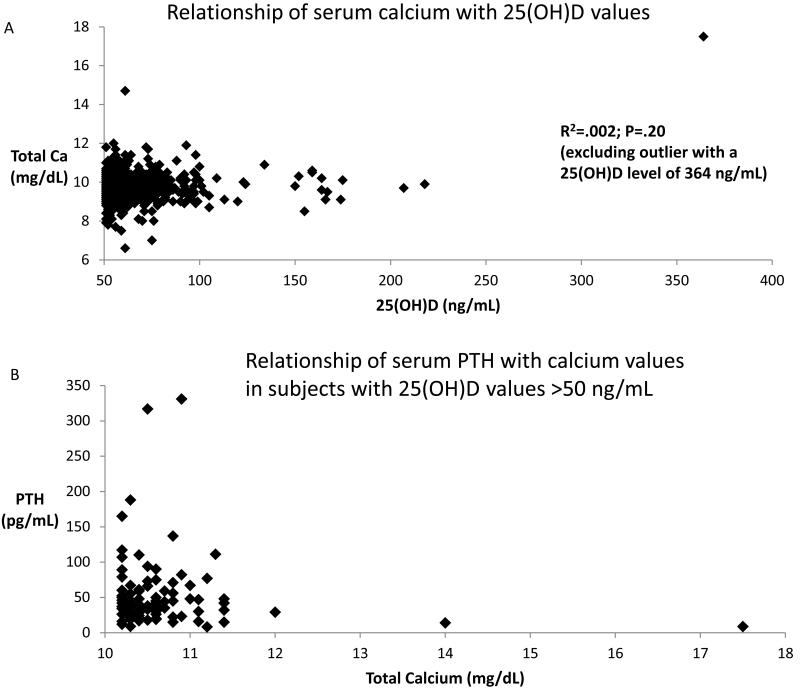

A total of 1070 subjects (62%) with 25(OH)D values >50 ng/mL had serum calcium measured within three months of the index date, with most serum calcium levels (78%) measured within one day of the index date (Figure 3). Of those with a serum calcium measured, 165 (15%) had hypercalcemia. In subjects who had 25(OH)D values 51-79, 80-99 or ≥100 ng/mL, the number with serum calcium measured within 3 months were 988 (62%), 56 (65%), and 26 (70%), respectively (Table 1). Of these, 151 (15%), 9 (16%), and 5 (19%), respectively, had hypercalcemia (P=.60 for trend).

Figure 3.

Bivariate plots of serum calcium, 25(OH)D, and PTH data in subjects with 25(OH)D values >50 ng/mL. (A) Relationship of total calcium with 25(OH)D concentrations (N=1035).(B) Relationship of PTH and total calcium (N=95).

In subjects with 25(OH)D values >50 ng/mL and hypercalcemia, 95 (58%) had a serum PTH measured within 3 months of the index date (Figure 3). Only 3 subjects (3%) had low PTH values (<10 pg/mL), with 21 (22%) in the normal range (10-27.5 pg/mL), 45 (47%) in the inappropriately high normal range for hypercalcemia (27.6-55 pg/mL),21 and 26 (27%) in the high range (>55 pg/mL). Of the three with low PTH, manual abstraction confirmed only one subject to have vitamin D toxicity (Table 2). There were no subjects who had documented sarcoidosis, tuberculosis, lymphoma or idiopathic infantile hypercalcemia, all known to cause hypervitaminosis D and hypercalcemia.

Table 2.

Clinical characteristics of subjects with hypercalcemia temporally associated with serum 25(OH)D >50 ng/mL.a

| Age | Sex | 25(OH)D (ng/mL) |

Serum Total Calcium (mg/dL) |

Vitamin D dose (IU) |

Calcium dose (mg/d) |

Clinical Presentation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 51 | F | 364 | 17.5 | 50,000 (1-4×/d) |

3000 | Anorexia, weight loss, fatigue, nausea, vomiting, confusion, headache, dyspnea, cough, hypertension, fever, Cr 3 (up from 1.3), PTH 8.7 |

| 87 | F | 100 | 10.8 | 50,000 (1×/d) |

1800 | Asymptomatic, no association with low PTH or elevated Cr |

| 46 | F | 90 | 10.2 | 50,000 (2×/wk) |

1200 | Asymptomatic, no association with low PTH or elevated Cr |

| 66 | F | 74 | 10.4 | 50,000 (1×/wk) |

1200 | Asymptomatic, no association with low PTH or elevated Cr |

Abbreviations: PTH, parathyroid hormone; Cr, creatinine; d, day; wk, week.

Regression analysis revealed no relationship between 25(OH)D levels and serum total calcium levels (R2=.002, P=.20) (Figure 3). In a multivariate analysis examining the effect of age, sex, 25(OH)D level and calendar year on the risk of hypercalcemia, 25(OH)D values were not associated with hypercalcemia (OR=1.01; P=.24). However, increasing age (OR=1.03; 95% CI=1.02-1.04), female gender (OR=1.7; 95% CI=1.1-2.8), and advancing calendar year (OR=1.1; 95% CI=1.02-1.23) were associated with an increased risk of hypercalcemia.

Medical records review of subjects with 25(OH)D values ≥100 ng/mL (n=37) confirmed ingestion of exogenous vitamin D supplements in all but one individual. Of these 36 subjects, 24 (67%) were taking at least 50,000 IU of either ergocalciferol (vitamin D2) or cholecalciferol (vitamin D3) from once weekly to once daily for a duration of one to over three months. In the remainder, the clinical notes indicated they were taking high doses of vitamin D supplements, but the dosages were not specified.

Of the 1714 subjects with 25(OH)D values >50 ng/mL, medical record abstraction revealed only four (0.2%) where the vitamin D concentration was associated temporally with hypercalcemia (Table 2). In these cases, the rise in calcium from normal to high values was temporally associated with vitamin D supplementation, resolution of hypercalcemia occurred after cessation of vitamin D supplementation, and no alternative explanation for the hypercalcemia (e.g. excess calcium ingestion or primary hyperparathyroidism) was documented, satisfying our definition of causality. All were adult women who were taking 50,000 IU of vitamin D at least weekly for a minimum of one month. Three cases had very mild hypercalcemia and remained asymptomatic with no associated low PTH or elevated creatinine values. The only case of clinical vitamin D toxicity was a 51 year old woman who presented with a 25(OH)D of 364 ng/mL and serum total calcium of 17.5 mg/dL. She was taking 50,000 IU vitamin D and 3000 mg calcium at least once daily for over three months. She presented with acute kidney injury in the setting of stage 3 chronic kidney disease, low PTH, and symptoms of severe hypercalcemia, including fatigue, anorexia, weight loss, nausea, vomiting and confusion.

Discussion

The incidence of 25(OH)D values >50 ng/mL rose significantly from 9 to 233 cases per 100,000 person-years between 2002 and 2011. The greatest increase was in females and in those aged ≥65 years. The increasing incidence trend remained significant even after adjusting for the rise in the annual number of 25(OH)D tests. The increasing incidence was also evident for values of 25(OH)D ≥80 ng/mL, with an increase from 1 to 15 per 100,000. Although the incidence trend was not significant for 25(OH)D values ≥100 ng/mL, likely due to the small sample size, there was still an increase from 0 to 5 per 100,000 from 2002 to 2011. The increasing incidence of 25(OH)D values >50 ng/mL is likely due to increasing vitamin D supplement use, both self- and physician-prescribed. We found no corresponding increase in acute clinical toxicity, which was only found in one subject with a 25(OH)D value of 364 ng/mL.

The prevalence of vitamin D supplementation in persons aged ≥14 years in the United States increased from 26% in 1988-1994 to 35% in 1999-2002 to 37% in 2003-2006, and it remained stable at 23-37% (varying by age) in children.22 In addition to vitamin D supplementation for osteoporosis, the explosion of studies tying vitamin D deficiency to many disease states has led to increased prescribing of vitamin D by physicians.3,5,23,24

In the US population during 2000-2004, the mean 25(OH)D concentration ranged from 23 ng/mL in the age group ≥70 years to 31 ng/mL in persons ages 1-5 years.25 The 25(OH)D values were lowest in females (25 ng/mL), non-Hispanic blacks (16 ng/mL), and in the winter (24 ng/mL). Globally, vitamin D deficiency is more prevalent in winter, females, older age groups, darker skinned individuals, and high latitudes.26-28 Our subjects were predominantly female (81%), aged ≥50 (69%), and white (93%), with higher vitamin D levels found in winter months. These characteristics resemble the demographics of individuals with vitamin D deficiency, suggesting that supplementation of those with or at higher risk of vitamin D deficiency may be occurring.

We found that 25(OH)D concentrations between 51 and 218 ng/mL did not significantly alter serum calcium values. This finding is consistent with literature reviews of clinically confirmed cases of vitamin D toxicity in both adults8 and children11 that show no relationship of serum calcium with 25(OH)D concentrations, even at 25(OH)D values of 200 to 700 ng/mL. Similarly, a recent study reported no relationship between vitamin D supplementation dose and hypercalcemia.29

The lack of association between 25(OH)D values >50 ng/mL and hypercalcemia was confirmed in multivariate analysis, although increasing age, female gender and calendar year were associated with an increased risk of hypercalcemia. Hypercalcemia probably resulted from other causes like primary or secondary hyperparathyroidism, thiazide diuretic use or calcium supplementation. Of the four cases of hypercalcemia that were temporally associated with elevated 25(OH)D values, only one had clinical symptoms of acute toxicity. This case was similar to cases previously reported in the literature.30,31 Most cases of acute vitamin D toxicity involve vitamin D doses of at least 50,000 IU and 25(OH)D concentrations of at least 140 ng/mL in adults7-9 and vitamin D doses above 240,000 IU and 25(OH)D values above 250 ng/mL in children.11

Our results agree with previous studies demonstrating that clinical vitamin D toxicity is rare, even with serum 25(OH)D concentrations >100 ng/mL. It is debatable how these findings apply to the most recent guidelines on vitamin D supplementation. The Endocrine Society guidelines, which target populations at risk of vitamin D deficiency, recommend a daily vitamin D intake of 10,000 IU as the UL, corresponding to a 25(OH)D concentration of 100 ng/mL.13 The UL is the maximum daily intake not expected to pose any harm to the general population. Even though we found three individuals with mild hypercalcemia attributed to 25(OH)D in the 51-100 ng/mL range, the clinical importance of this is not clear. These patients had no associated low PTH, which would be expected to be suppressed, and no clinical symptoms. Thus our results support the position that 25(OH)D values up to 100 ng/mL are unlikely to cause acute harm.

Even if 25(OH)D values >50 ng/mL, or even >100 ng/mL, are unlikely to cause acute toxicity, achieving 25(OH)D values >50 ng/mL has not been demonstrated to be beneficial, especially for the general population. On the contrary, several studies have shown an association between 25(OH)D concentrations above 30-60 ng/mL and increased risk of all-cause mortality,32-34 cardiovascular disease,32,35,36 cancers,37-39 falls and fractures.40,41 Furthermore, even in latitudes close to the equator, maximal sun or other ultraviolet light exposure seldom raises 25(OH)D values above 50-60 ng/mL.42-44 Without significant sun exposure, achieving a 25(OH)D concentration >50 ng/mL requires vitamin D ingestion of approximately 4,000 IU/day in persons >8 years of age,8 which has been defined as the UL for vitamin D by the IOM.7 Thus, although it is reassuring that acute vitamin D toxicity is only associated with extreme 25(OH)D values, the potential for chronic adverse events is concerning and requires further study.

The strengths of our study include a large community-based population and access to all follow-up they may have had related to acute toxicity from primary through tertiary care. However, as anticipated in a retrospective analysis, our study had limitations. First, because only those in the population with a 25(OH)D measurement were included, additional individuals with 25(OH)D values >50 ng/mL who were not tested may not have been recognized, and the true incidence may be greater than we identified. Second, of those with 25(OH)D values >50 ng/mL, 38% had no concurrent calcium measurement, and the incidence of hypercalcemia associated with 25(OH)D may have been underestimated. Third, few subjects were assessed for hypercalciuria, which could be present in the absence of hypercalcemia and reflect acute toxicity. Fourth, we only examined acute toxicity and did not evaluate potential long term adverse effects of 25(OH)D values >50 ng/mL.

Conclusion

We provide evidence in a northern population that the incidence of 25(OH)D values >50 ng/mL increased dramatically from 2002-2011, without a corresponding increase in acute clinical toxicity. High-dose intermittent vitamin D supplementation has become established as a means of quickly restoring vitamin D status to normal and of improving adherence. We found that most cases of 25(OH)D levels >100 ng/mL were associated with prolonged use of high-dose vitamin D supplements, which are available without a prescription. Until further studies demonstrate the safety of maintaining 25(OH)D values >50 ng/mL, we recommend monitoring serum 25(OH)D and calcium when using intermittent vitamin D doses ≥50,000 IU (or daily doses ≥4,000 IU) on a continued bases. We would also encourage greater awareness by health providers of the doses of non-prescription vitamin D used by their patients.

Acknowledgements

We thank Barbara Abbott (Rochester Epidemiology Project, Data Collection, Mayo Clinic) for her help with acquisition of data from the REP database. We thank Brian Kabat, BS, Carin Smith, BS, and Kelly Edwards, BA (Department of Health Science Research, Mayo Clinic), and Richard Zeller (Department of Research, Olmsted Medical Center), for their assistance with lab data retrieval. None received direct compensation for their contributions.

Financial support

This study was made possible using the resources of the Rochester Epidemiology Project, which is supported by the National Institute of Aging of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) under Award Number R01AG034676. The study was also supported by the Mayo Clinic CTSA through grant number UL1 TR000135 from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS), a component of the NIH. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH.

Abbreviations

- 25(OH)D

25-hydroxyvitamin D

- REP

Rochester Epidemiology Project

- IOM

Institute of Medicine

- UL

Tolerable Upper Intake Level

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Disclosure

Dr. Tom Thacher is a consultant for Biomedical Systems. The other authors have nothing to disclose.

Contributor Information

Daniel V. Dudenkov, Department of Internal Medicine, Mayo Clinic.

Barbara P. Yawn, Olmsted Medical Center.

Sara S. Oberhelman, Department of Family Medicine, Mayo Clinic.

Philip R. Fischer, Department of Pediatric and Adolescent Medicine, Mayo Clinic.

Ravinder J. Singh, Department of Laboratory Medicine and Pathology, Mayo Clinic.

Stephen S. Cha, Department of Health Science Research, Mayo Clinic.

Julie A. Maxson, Department of Family Medicine, Mayo Clinic.

Stephanie M. Quigg, Department of Family Medicine, Mayo Clinic.

Tom D. Thacher, Department of Family Medicine, Mayo Clinic.

References

- 1.Thacher TD, Clarke BL. Vitamin D insufficiency. Mayo Clin Proc. 2011;86(1):50–60. doi: 10.4065/mcp.2010.0567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bailey RL, Dodd KW, Goldman JA, et al. Estimation of total usual calcium and vitamin D intakes in the United States. J Nutr. 2010;140(4):817–822. doi: 10.3945/jn.109.118539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sanders KM, Nicholson GC, Ebeling PR. Is high dose vitamin D harmful? Calcif Tissue Int. 2013;92(2):191–206. doi: 10.1007/s00223-012-9679-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hansen KE. High-dose vitamin D: helpful or harmful? Curr Rheumatol Rep. 2011;13(3):257–264. doi: 10.1007/s11926-011-0175-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kearns MD, Alvarez JA, Tangpricha V. Large, Single-Dose, Oral Vitamin D Supplementation in Adult Populations: A Systematic Review. Endocr Pract. 2013:1–36. doi: 10.4158/EP13265.RA. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brannon PM, Yetley EA, Bailey RL, Picciano MF. Overview of the conference “Vitamin D and Health in the 21st Century: an Update”. Am J Clin Nutr. 2008;88(2):483S–490S. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/88.2.483S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ross AC, Taylor CL, Yaktine AL, Del Valle HB, editors. Dietary References Intakes for Calcium and Vitamin D. The National Academies Press; Washington, D.C.: 2011. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vieth R. Vitamin D toxicity, policy, and science. J Bone Miner Res. 2007;22(Suppl 2):V64–68. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.07s221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jones G. Pharmacokinetics of vitamin D toxicity. Am J Clin Nutr. 2008;88(2):582S–586S. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/88.2.582S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Koul PA, Ahmad SH, Ahmad F, Jan RA, Shah SU, Khan UH. Vitamin D toxicity in adults: a case series from an area with endemic hypovitaminosis D. Oman Med J. 2011;26(3):201–204. doi: 10.5001/omj.2011.49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vogiatzi MG, Jacobson-Dickman E, Deboer MD. Vitamin D supplementation and risk of toxicity in pediatrics: a review of current literature. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2014;99:1132–1141. doi: 10.1210/jc.2013-3655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hathcock JN, Shao A, Vieth R, Heaney R. Risk assessment for vitamin D. Am J Clin Nutr. 2007;85(1):6–18. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/85.1.6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Holick MF, Binkley NC, Bischoff-Ferrari HA, et al. Evaluation, treatment, and prevention of vitamin D deficiency: an Endocrine Society clinical practice guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2011;96(7):1911–1930. doi: 10.1210/jc.2011-0385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Melton LJ., 3rd History of the Rochester Epidemiology Project. Mayo Clin Proc. 1996;71(3):266–274. doi: 10.4065/71.3.266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.St Sauver JL, Grossardt BR, Yawn BP, Melton LJ, 3rd, Rocca WA. Use of a medical records linkage system to enumerate a dynamic population over time: the Rochester Epidemiology Project. Am J Epidemiol. 2011;173(9):1059–1068. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwq482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kurland LT, Molgaard CA. The patient record in epidemiology. Sci Am. 1981;245(4):54–63. doi: 10.1038/scientificamerican1081-54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yawn BP, Yawn RA, Geier GR, Xia Z, Jacobsen SJ. The impact of requiring patient authorization for use of data in medical records research. J Fam Pract. 1998;47(5):361–365. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jacobsen SJ, Xia Z, Campion ME, et al. Potential effect of authorization bias on medical record research. Mayo Clin Proc. 1999;74(4):330–338. doi: 10.4065/74.4.330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.St Sauver JL, Grossardt BR, Leibson CL, Yawn BP, Melton LJ, 3rd, Rocca WA. Generalizability of epidemiological findings and public health decisions: an illustration from the Rochester Epidemiology Project. Mayo Clin Proc. 2012;87(2):151–160. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2011.11.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rocca WA, Yawn BP, St Sauver JL, Grossardt BR, Melton LJ., 3rd History of the Rochester Epidemiology Project: half a century of medical records linkage in a US population. Mayo Clin Proc. 2012;87:1202–1213. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2012.08.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kao PC, van Heerden JA, Grant CS, Klee GG, Khosla S. Clinical performance of parathyroid hormone immunometric assays. Mayo Clin Proc. 1992;67:637–645. doi: 10.1016/s0025-6196(12)60717-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gahche J, Bailey R, Burt V, et al. Dietary supplement use among U.S. adults has increased since NHANES III (1988-1994) NCHS Data Brief. 2011;(61):1–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pludowski P, Holick MF, Pilz S, et al. Vitamin D effects on musculoskeletal health, immunity, autoimmunity, cardiovascular disease, cancer, fertility, pregnancy, dementia and mortality-a review of recent evidence. Autoimmun Rev. 2013;12:976–989. doi: 10.1016/j.autrev.2013.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Robbins J. ACP Journal Club. Review: high-dose oral vitamin D supplements and active vitamin D prevent falls in older persons. Ann Intern Med. 2010;152(2):JC1–3. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-152-2-201001190-02003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Looker AC, Pfeiffer CM, Lacher DA, Schleicher RL, Picciano MF, Yetley EA. Serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D status of the US population: 1988-1994 compared with 2000-2004. Am J Clin Nutr. 2008;88(6):1519–1527. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.2008.26182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Holick MF. Vitamin D deficiency. N Engl J Med. 2007;357(3):266–281. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra070553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lips P. Worldwide status of vitamin D nutrition. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2010;121(1-2):297–300. doi: 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2010.02.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gozdzik A, Barta JL, Wu H, et al. Low wintertime vitamin D levels in a sample of healthy young adults of diverse ancestry living in the Toronto area: associations with vitamin D intake and skin pigmentation. BMC Public Health. 2008;8:336. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-8-336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ekwaru JP, Zwicker JD, Holick MF, Giovannucci E, Veugelers PJ. The importance of body weight for the dose response relationship of oral vitamin D supplementation and serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D in healthy volunteers. PloS One. 2014;9(11):e111265. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0111265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schwartzman MS, Franck WA. Vitamin D toxicity complicating the treatment of senile, postmenopausal, and glucocorticoid-induced osteoporosis. Four case reports and a critical commentary on the use of vitamin D in these disorders. Am J Med. 1987;82(2):224–230. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(87)90060-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Davies M, Adams PH. The continuing risk of vitamin-D intoxication. Lancet. 1978;2(8090):621–623. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(78)92838-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Melamed ML, Michos ED, Post W, Astor B. 25-hydroxyvitamin D levels and the risk of mortality in the general population. Arch Intern Med. 2008;168(15):1629–1637. doi: 10.1001/archinte.168.15.1629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Amrein K, Quraishi SA, Litonjua AA, et al. Evidence for a U-shaped relationship between pre-hospital vitamin D status and mortality: a cohort study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2014 doi: 10.1210/jc.2013-3481. jc20133481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Durup D, Jorgensen HL, Christensen J, Schwarz P, Heegaard AM, Lind B. A reverse J-shaped association of all-cause mortality with serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D in general practice: the CopD study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2012;97(8):2644–2652. doi: 10.1210/jc.2012-1176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ginde AA, Scragg R, Schwartz RS, Camargo CA., Jr Prospective study of serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D level, cardiovascular disease mortality, and all-cause mortality in older U.S. adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2009;57(9):1595–1603. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2009.02359.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fiscella K, Franks P. Vitamin D, race, and cardiovascular mortality: findings from a national US sample. Ann Fam Med. 2010;8(1):11–18. doi: 10.1370/afm.1035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chlebowski RT, Johnson KC, Kooperberg C, et al. Calcium plus vitamin D supplementation and the risk of breast cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2008;100(22):1581–1591. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djn360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Stolzenberg-Solomon RZ, Jacobs EJ, Arslan AA, et al. Circulating 25-hydroxyvitamin D and risk of pancreatic cancer: Cohort Consortium Vitamin D Pooling Project of Rarer Cancers. Am J Epidemiol. 2010;172(1):81–93. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwq120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tuohimaa P, Tenkanen L, Ahonen M, et al. Both high and low levels of blood vitamin D are associated with a higher prostate cancer risk: a longitudinal, nested case-control study in the Nordic countries. Int J Cancer. 2004;108(1):104–108. doi: 10.1002/ijc.11375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sanders KM, Stuart AL, Williamson EJ, et al. Annual high-dose oral vitamin D and falls and fractures in older women: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2010;303(18):1815–1822. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Smith H, Anderson F, Raphael H, Maslin P, Crozier S, Cooper C. Effect of annual intramuscular vitamin D on fracture risk in elderly men and women--a population-based, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2007;46(12):1852–1857. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kem240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Luxwolda MF, Kuipers RS, Kema IP, Dijck-Brouwer DA, Muskiet FA. Traditionally living populations in East Africa have a mean serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D concentration of 115 nmol/l. Br J Nutr. 2012;108(9):1557–1561. doi: 10.1017/S0007114511007161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Barger-Lux MJ, Heaney RP. Effects of above average summer sun exposure on serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D and calcium absorption. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2002;87(11):4952–4956. doi: 10.1210/jc.2002-020636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tangpricha V, Turner A, Spina C, Decastro S, Chen TC, Holick MF. Tanning is associated with optimal vitamin D status (serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D concentration) and higher bone mineral density. Am J Clin Nutr. 2004;80(6):1645–1649. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/80.6.1645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]