Abstract

Opioid peptides and their receptors have been localized to the inner ear of the rat and guinea pig mammalian models. The expression of mu opioid receptor (MOR) in the human and mouse cochlea is not yet known. We present MOR protein localization by immunohistochemistry and mRNA expression by in situ hybridization in the human and mouse spiral ganglia (SG) and organ of Corti. In the human most of the (SG) neurons were immunoreactive; a subset was non-immunoreactive. In situ hybridization revealed a similar labeling pattern across the neurons of the SG. A similar distribution MOR pattern was demonstrated in the mouse SG. In the mouse organ of Corti MOR was expressed in inner and outer hair cells. Fibers underneath the inner hair cells were also MOR immunoreactive. These results are consistent with a role of MOR in neuro-modulation of the auditory periphery. The present results show that the expression of MORs is well-conserved across multiple mammalian species, indicative of an important role in auditory processing.

Keywords: Cochlea, Spiral ganglia neurons, Afferent terminals, Neuropeptides, Opioid receptors

Introduction

The opioid peptides are a family of over twenty endogenous neuromodulators that are produced by neurons throughout the mammalian central nervous system. They bind to and activate seven transmembrane guanine nucleotide-binding protein coupled opioid receptors (Waldhoer et al., 2004; Zuo, 2005). Opioid receptors are located through the body, and regulate a number of important behaviors such as reward, pain, stress, gastrointestinal transport and mood through receptors in both the central and peripheral nervous system (Pradhan et al., 2012). There are four types of opioid receptors—mu-opioid receptor (MOR), kappa-opioid receptor (KOR), delta-opioid receptor (DOR), and nociceptin opioid receptor (NOP) (McDonald and Lambert, 2005; Waldhoer et al., 2004). MOR is involved in respiration, cardio vascular function, thermo regulation, immune function, and gastrointestinal motility, along with the mediation of common analgesia and euphoria pathways (Contet et al., 2004; McDonald and Lambert, 2005). Knockout studies in mice show that the MOR is essential for morphine-induced analgesia, genetic variation of the MOR gene (OPRM1) has been associated with variation in opioid response in different setting including acute post-operative pain, chronic non-cancer pain and cancer related pain (revised by Branford et al., 2012). In addition to binding endogenous opioid peptides, opioid receptors are also the target of analgesic and psychoactive opioid agents that are often prescribed for analgesia, as well as commonly used for recreational purposes. Frequently- used opioids include morphine, codeine, hydrocodone, heroine, and cocaine. Studies have shown that a staggering 90% of patients with chronic pain rely on opioid medications for analgesia, and additionally 5.6% of the adult population uses opioids for non-medicinal purposes (United Nations, 2011). Well-known side effects of opioids include dizziness, nausea, vomiting, respiratory depression, and death in overdose (Trescot et al., 2008, 2010). A less well-known adverse effect of opioids is sudden or rapidly-progressive sensorineural hearing loss. Multiple reports have linked hydrocodone/acetaminophen, oxycodone/acetaminophen, propoxyphene, heroin, cocaine, methadone, and amphetamine use with severe to profound sensorineural hearing loss (Christenson and Marjala, 2010; Ciorba et al., 2009; Fowler and King, 2008; Friedman et al., 2000; Harell et al., 1978; Ho et al., 2007; Iqbal, 2004; Ishiyama et al., 2001; Oh et al., 2000; Rigby and Parnes, 2008; Schrock et al., 2008; Stenner et al., 2009; van Gaalen et al., 2009). Some of these studies reported individuals that used legally-prescribed medications, such as Vicodin, not always at high doses, but sometimes within the recommended dosages. In some cases, the bilateral hearing loss is irreversible, and cochlear implantation restores functional hearing (Freeman et al., 2009; Friedman et al., 2000; Ho et al., 2007; Oh et al., 2000).

Opioid neuropeptides (enkephalins) and their receptors are expressed in both the central and peripheral auditory system. Fex and Altschuler (1981) demonstrated the existence of encephalin-like immunoreactivity in the organ of Corti of the guinea pig and cat. Studies on the distribution of opioid receptors in the auditory and vestibular periphery have been conducted also in the rat and guinea pig cochlea (Jongkamonwiwat et al., 2003, 2006) using immunocytochemistry, western blot and RT-PCR. All four opioid receptor subtypes (MOR, DOR, KOR and ORL) were detected. Prior studies have localized MOR to the auditory and vestibular systems of several mammalian and amphibian species. Specifically, MOR has been found in the supporting cells and spiral ganglia of the rat (Jongkamonwiwat et al., 2003), as well as in the inner and outer hair cells, Deiter’s cells, and the inner and outer spiral bundles of the guinea pig (Jongkamonwiwat et al., 2006). In the rat vestibular periphery, MOR mRNA and protein expression has been discovered in the calyceal and bouton afferents (Popper et al., 2004). The functionality of opioid receptors in the inner ear has been previously investigated (Vega and Soto 2003, Lioudyno et al., 2000). Opioid drugs effects on auditory evoked potentials suggest a role of lateral olivocochlear dynorphins in auditory function (Sahley et al., 1991); opioid receptors inhibit the adenylate cyclase in guinea pig cochleas (Eybalin et al. 1987); opioid receptors mediate a postsynaptic facilitation and a presynaptic inhibition at the afferent synapse in axolotl vestibular hair cells (Vega and Soto, 2003); the alpha9/ alpha10-containing nicotinic Ach receptor is directly modulated by opioid peptides (Lioudyno et al., 2000). This type of opposed pre-and postsynaptic action is typical of opioid receptors and accounts for the state-dependent activity of peptide neuromodulators (Soto and Vega, 2010). Despite multiple studies demonstrating the presence of MOR in the inner ear of various animal models, MOR has yet to be localized to either the human or mouse cochlea. In the present study using immunocytochemistry and in situ hybridization we study the expression of MOR in the human and mouse auditory periphery. We found a similar expression of MOR in the cochlea of both species.

2. Results

MOR Immunoreactivity (-IR) in the human SGNs

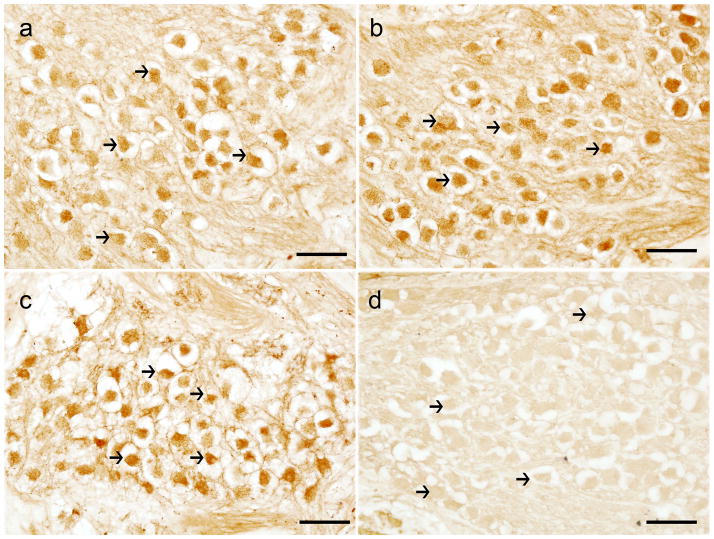

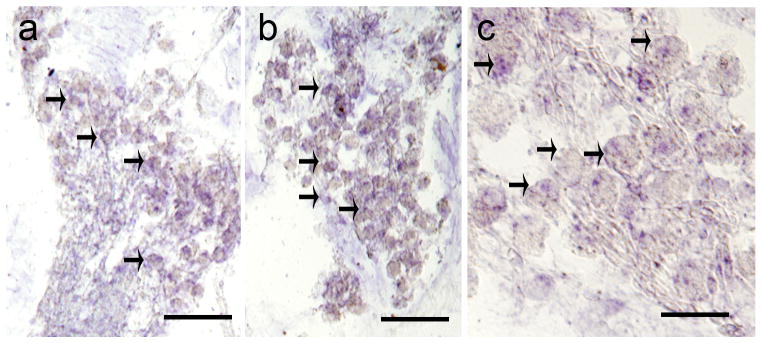

MOR-IR was visualized by indirect immunohistochemistry using horse-radish peroxidase and the chromogen diaminobenzidine (Fig. 1). Immunoreactivity was confined to neuronal somata, nuclei was non-immunoreactive. Moderated immunoreactivity was seen in nerve fibers than intermingle with the neurons in the SG. Satellite cells that surround SGNs were not immunoreactive to MOR antibodies. MOR-IR was present in most SGNs at the apical (Fig. 1a), middle (Fig. 1b) and basal (Fig. 1c), levels of the cochlea. The pattern of immunoreactivity was similar in the three levels, and consistent in all specimens immunoreacted with MOR antibody. Fig. 1d, shows a negative control; MOR antibody was omitted in the immunoreaction, and SGNs were not immunostained.

Figure 1.

Distribution of MOR-mRNA-positive cells in the human SGNs

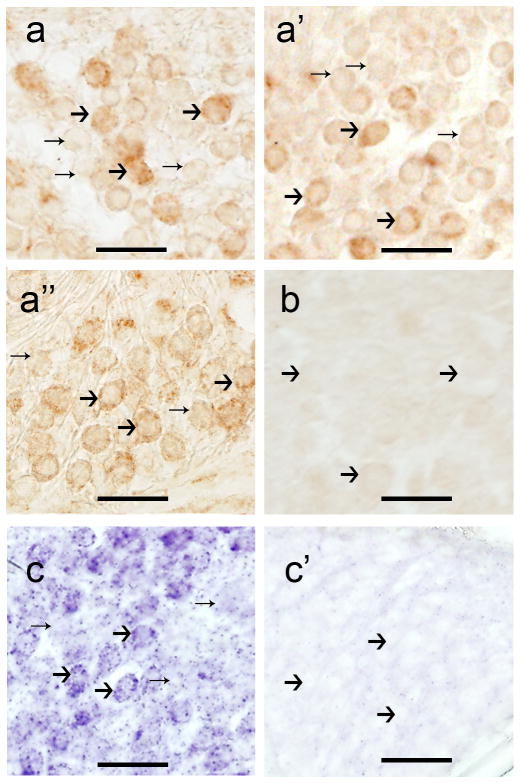

A digoxigenin-labeled antisense oligonucleotide probe for the human and mouse MOR was used to detect the expression of MOR in the human and mouse SGNs. MOR-mRNA positive neurons were detected in the SGNs. The expression pattern detected by in situ hybridization was similar to the one obtained by immunocytochemistry. Fig. 2a and b shows SGNs from two regions of the cochlea (base and middle portion). Fig. 2c shows a high magnification view. MOR-mRNA is present in most of the SGNs somata. The staining pattern was similar in the neurons of the human SG from the base to the apical portion. Consistent positive signal was seem among the specimens stained.

Figure 2.

MOR-IR and mRNA in the mouse SGNs

In the mouse SG, MOR-IR was present in the soma of thighs, their nuclei were non-reactive. Neurons were immunoreactive to the MOR antibody at the apical (Fig. 3a), middle (Fig. 3a′), and basal (Fig. 3a″) levels of the SG; however, some neurons showed stronger signal. Immunoreactive and non-immunoreactive neurons were of similar size. Fig. 3b is a negative control, primary antibody was omitted no immunoreaction was observed. MOR-mRNA signal pattern was similar to the immunoreactive pattern; most of the neurons showed MOR-mRNA positive signal (Fig. 3c). Fig. 3c′ shows SGNs hybridized with sense strands, in which no signal was detected.

Figure 3.

MOR-IR in the mouse organ of Corti

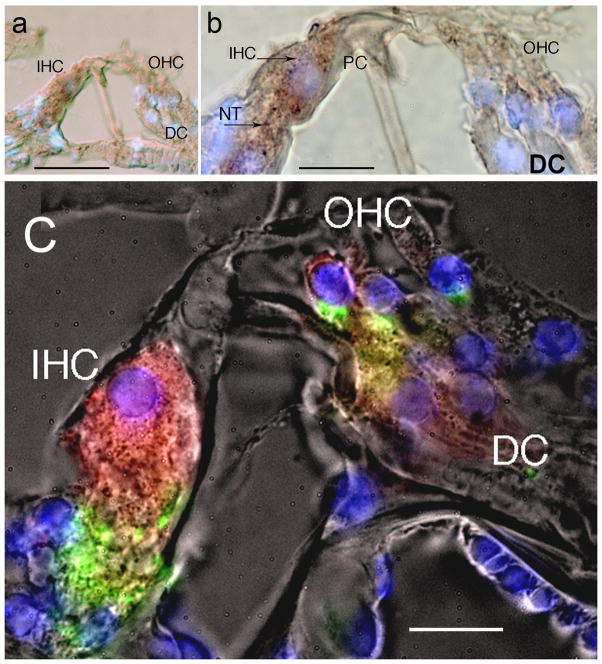

Fluorescent immunostaining in the organ of Corti showed that MOR-IR localized in the inner (IHC) and outer hair cells (OHC), and the IHC afferents (red color). Immunolabeling was strong in the IHC, and in the fibers beneath the IHC, presumably afferent nerve fibers to the IHC (Fig. 4A). Labeling was also present in the OHC, and there was mild labeling of Deiter’s cells (Fig. 4A). There was no evidence of MOR immunoreactive terminals beneath the OHC (Fig. 4A). Synaptophysin immunoreactivity (in green) was used to label efferent terminals beneath the inner and outer hair cells. MOR-IR (red color) does not colocalize with synaptophysin (green color) immunoreactivity. Fig. 4B from another mouse cochlea showed that the IHCs and the peripheral processes beneath were MOR-IR, OHCs and Deiter’s cells showed also MOR-IR. Tunnel crossing fibers within the tunnel of Corti were non-immunoreactive. The distribution of MOR-IR in the organ of Corti was similar in the basal, medial, and apical regions.

Figure 4.

3. Discussion

In the present report, we present the first MOR expression in the human and mouse cochlea using immunohistochemistry and mRNA expression by in situ hybridization. Human SGNs were MOR-IR at the basal, middle, and apical turns of the cochlea, and these findings were supported by mRNA expression detected by non-radioactive in situ hybridization. Mouse SGNs also showed similar localization patterns, as confirmed by both immunocytochemistry and in situ hybridization methods. In the organ of Corti MOR was expressed in inner and outer hair cells as well as putative afferent terminals that innervate them.

3.1. Opioid receptor expression in other mammalian species

Our results in the human and mouse cochlea are consistent with prior investigations of other mammalian species, which have identified MOR in the cochlea of the guinea pig and rat. MOR-IR in the mouse organ of Corti was similar to that reported in the guinea pig (Jongkamonwiwat et al., 2006). Using RT-PCR and immunohistochemical assays, Jongkamonwiwat et al. (2006) localized MOR to the guinea pig inner and outer spiral bundles, and to the guinea pig inner and outer hair cells. Studies in the rat model from the same laboratory also localized MOR in the bipolar cells and nerve fibers of the rat spiral ganglion, as well as in the region located beneath the outer hair cells, but not in the inner and outer hair cells themselves or in the interdental cells (Jongkamonwiwat et al., 2003). Given to the fragility and postmortem artifact of the human of Corti we were not able to localize MOR-IR to specific cells, however, human SGNs were more resistant to postmortem degeneration allowing the detection of both MOR protein and mRNA by immunohistochemistry and non radioactive in situ hybridization. Within the mammalian vestibular periphery, MOR expression has been reported in the somata of vestibular afferents and the nerve terminals of the cristae ampullaris epithelia in the rat (Popper et al., 2004). Other opioid receptors have been localized to the auditory periphery, as well. For example the orphanin FQ/ nociception (OFQ/N) (Kho et al., 2006) and its receptor (ORL-1) have been proposed to play a role in hearing regulation (Nishi et al., 1997).

3.2. Activation of MOR in the mammalian auditory periphery

In light of the increasing reports of opioid-induced deafness, we explored a potential mechanism of opioid-induced hearing loss. It has been postulated that MORs on the outer hair cells may be activated by endogenous opioid peptides produced by medial efferent fibers, while MORs role on the inner hair cells is more difficult to explain and suggest inactive receptor or reminder from developmental expression (Jongkamonwiwat et al., 2006). The latter maybe an example of autocrine regulation causing feedback inhibition (Popper et al., 2004). Studies have also shown that opioid receptors may act as both pre-and post-synaptic receptors (Besse et al., 1990; Bourgoin et al., 1994; Honda and Arvidsson, 1995). Our findings suggests that this maybe the case in the human and mouse cochlea. We do not rule out that KOR and DOR may be also expressed in both the mouse and human and cochlea. Previous studies showing that opioids affect the excitability of the inner ear may explain why exogenous opioid agents such as vicodin, heroin, and cocaine, (which are commonly known to bind opioid receptors throughout the body) can produce significant alterations in hearing and balance (Soto and Vega, 2010). It is important to consider also that these drugs are used in excess and sensorineural hearing loss also might be caused by the ototoxicity of additives i.e. parcetamol (acetaminophen) combined with hydrocodone.

3.3. Opioid-associated sensorineural hearing loss

Recently, there have been multiple reports of sudden or rapidly-progressive sensorineural hearing loss occurring in association with opioid use in mostly young, otherwise healthy patients (reviewed by Lopez et al., 2012). Hydrocodone/ acetaminophen has been implicated in cases of bilateral, irreversible profound hearing loss, both in patients who abide by the recommended daily dosages, as well as in those who chronically abuse the compound for recreational purposes. These patients eventually require cochlear implantation to obtain functional hearing because of permanent deafness. Heroin, cocaine, and methadone use, on the other hand, has been linked to profound hearing loss that is reversible in some cases and irreversible in others. The literature varies on the route of administration, ranging from intravenous injection to oral consumption to inhalation, as well as on the amount and duration of use, ranging from the first episode of use to chronic use lasting over 20 years (Christenson and Marjala, 2010; Ciorba et al., 2009; Fowler and King, 2008; Friedman et al., 2000; Harell et al., 1978; Ho et al., 2007; Iqbal, 2004; Ishiyama et al., 2001; Oh et al., 2000; Rigby and Parnes, 2008; Schrock et al., 2008; Stenner et al., 2009; van Gaalen et al., 2009). Some patients have recovered their hearing after a course of steroids and pentoxifylline, while others have recovered spontaneously, usually within one month of onset. Other opioids that have been linked to hearing loss include propoxyphene (Harell et al., 1978; Lupin and Harley, 1976; Ramsay, 1991), which may cause a permanent sensorineural hearing loss, morphine (Nitescu et al., 1995), a codeine/ acetaminophen combination (Blakley and Schilling, 2008), and percocet which contain oxycodone and acetaminophen (Rigby and Parnes, 2008).

Of note, several reports of heroin-associated hearing loss involved subjects longed abstinence (Ishiyama et al., 2001; Schrock et al., 2008), suggesting that the opioid system undergoes a period of tolerance followed by resensitization, or that the system develops a hypersensitive condition after a withdrawal period. However, there have also been reports of patients who lose their hearing after overdosing and losing consciousness, suggesting that the opioid system becomes overloaded or hyperstimulated prior to the development of profound hearing loss (Antonopoulos et al., 2012; Christenson and Marjala, 2010; Fowler and King, 2008; Polpathapee et al., 1984; Schrock et al., 2008; van Gaalen et al., 2009). It is important to mention that opioid peptide receptors and opioid peptides are also present in the vestibular periphery (revised in Soto and Vega, 2010), and drugs such as heroin and hydrocodone, can produce significant alteration in balance and hearing. The molecular mechanisms of opioid receptors is beginning to be elucidated, in vestibular afferents of the rat the activation of MOR receptors inhibit calcium-currents through a cAMP dependent mechanism (Seseña et al., 2014). It is likely that opiate-associated hearing loss results from the interaction of exogenous opioids with opioid receptors within the inner ear. MOR, compared to the other opioid receptors, is known to be more selectively activated by opioid analgesics; and specifically, the receptors that we have identified within the spiral ganglion neurons maybe the target sites associated with opioid-induced hearing loss. A specific mechanism on how MOR activation can lead to hearing loss remains to be determined. Various mechanisms have been proposed for example heroin a MOR agonist could bind to MOR receptors in the cochlea and provoke down regulation of auditory sensitivity (Schrock et al., 2008) or a resensitization of a tolerized opioid system and a prolonged hypersensitization of the system secondary to withdrawal, hearing loss maybe caused by the ototoxicity of heroin- adulterant additives such a quinine that damages outer hair cells of the cochlea (Ishiyama et al., 2001).

3.4. Conclusions

The pattern of MOR immunolocalization and mRNA expression (using in situ hybridization) in the human and mouse cochlea is consistent with those of other mammalian species, and suggests that endogenous opioid peptides and their receptors may play an important role in auditory neuromodulation. MOR sensitization maybe involved in opioid-induced hearing loss.

4. Experimental procedures

4.1. Human specimens

The Institutional Review Board (IRB) of UCLA has approved this study. Appropriate informed consent for inclusion in the study was obtained from each temporal bone donor before death. The temporal bone donors in the present study are part of a National Institute of Health funded Human Temporal Bone Consortium for Research Resource Enhancement through the National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders. Temporal bones were obtained at autopsy from 2 subjects (67 and 82 year old, male and female respectively) with a documented history of normal auditory and vestibular function (In situ hybridization). The postmortem time was 6h and 10h. The whole cochlea was microdissected from one temporal bone from each donor. Immunocytochemistry in celloidin embedded sections was made in three specimens with normal auditory function. 72 year old male, 65 year old female and 82 year old male.

4.2. Human temporal bone removal and cochlea microdissection

At autopsy, the whole brain, including the brainstem and blood vessels, was removed from the cranial cavity. The temporal bones were removed as described previously using a bone plug cutter (Lopez et al., 2005). The bones were then immediately immersed for 16h in cold 4% paraformaldehyde in 0.11 M sodium phosphate buffer (PBS), pH7.4. Thereafter, the fixative was removed by washing with PBS (10 min × 3). Temporal bones were placed under a dissecting microscope (Nikon SMZ1500), and the bone surrounding the membranous labyrinth was carefully removed as described previously (Lopez et al., 2005).

4.3. Immunohistochemistry in celloidin embedded sections

Celloidin removal: Temporal bone specimens were all formalin fixed celloidin embedded (FFCE). Celloidin was removed from the cochlea sections as previously described (Ahmed et al., 2013). Sections were then subjected to the antigen retrieval step (Balaker et al., 2013). Immunohistochemistry: The protocol for immunocytochemistry was described in detail by Balaker et al. (2013). Tissue sections were incubated for 48h at 4C, with the MOR antibodies. The MOR antibody was kindly donated by Christopher J. Evans, (David Geffen School of Medicine at UCLA) and additional studies were conducted using MOR antibody (Chemicon). The MOR antibody was derived from rabbit polyclonal antiserum raised against the synthetic peptide LENLEAE-TAPLP which corresponds to the carboxyl terminal 12 amino acids (387–398) of the mouse MOR. The antiserum is affinity purified on an antigen-coupled Sepharose column. The antibody recognizes the MOR termed MOR1, but not C-terminal splice variants of the mouse MOR, namely MOR1C, MOR1D, and MOR1E (Pan et al., 1999).

4.4. Human cochlea processing for in situ hybridization

The microdissected cochlea was immersed in sucrose 30% (in PBS) for 5 days, and then infiltrated in O.C.T. compound (Tissue Tek, Ted Pella, Redding, CA). Before sectioning, the whole cochlea was placed on a Teflon embedding mold (Polysciences Inc., Warrington, PA) and properly oriented (under the dissecting microscope) to obtain longitudinal mid-modiolar serial sections of cochlea. Twenty-micron- thick serial sections were obtained using a cryostat (Microm-HN505E). Sections were mounted on Superfrost plus slides (Fisher Scientific, Pittsburgh, PA) and stored at −80C until their use.

4.5. Mouse tissue preparation for immunohistochemistry and in situ hybridization

Four young male mice (C57BL/6, age range from one to three months and 50–70 g weight) were used in the present study. Mice were over anesthetized with halothane and then decapitated. The temporal bones were removed from the skull and immersed immediately in 4% paraformaldehyde for 24h. Twenty micron thick sections were obtained, indirect immunohistochemistry using HRP-DAB were performed as described above and according to Lopez et al. (2005). The methodology for immunofluorescence has been described by us recently (Balaker et al., 2013). Tissue cryostat sections were incubated for 16h at 4C with a mixture of the primary antibody against MOR (same as above) and monoclonal antibodies against synaptophysin (Boehringer Mannheim Biochemica, Mannheim, Germany) diluted 1:100. Sections were washed with PBS (3×10 min) and covered with Vectashield mounting media (VectorLabs, Burlingame, CA) containing DAPI to visualize cell nuclei. The Chancellor’s Animal Subject Protection Committee at the University of California, Los Angeles, approved the research protocols for the use of animal subjects in this study. Animals were handled and cared for in accordance with the Animal Welfare Act and in strict compliance with the National Institute of Health Guidelines.

4.6. Immunohistochemistry controls

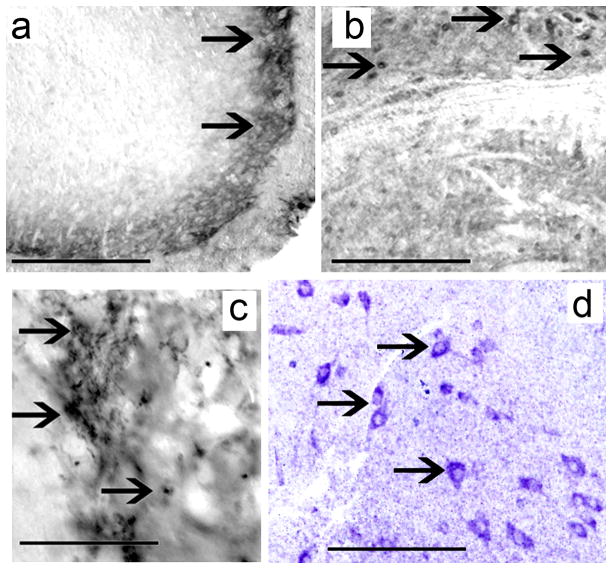

Positive controls: Wild type mouse spinal cord (Fig. 5a), brainstem (Fig. 5b), and hippocampus (Fig. 5c) cross sections were immunoreacted with MOR antibodies. The distribution of MOR-IR was similar to previously published reports (Arvidsson et al., 1995). As negative control human and mouse cochlea tissue sections were processed for immunocytochemistry as described above, except that the MOR primary antibody was omitted. There was no MOR-IR in the human (Fig. 1d) or mouse cochlea (Fig. 3b) in sections without MOR primary antibody.

Figure 5.

4.7. In situ hybridization

Source of probes for in situ hybridization: Oligonucleotide probes specific to the MOR mRNA sequence (Gen Bank accession no. NM_001039652.1 for the mouse probe, and NM_000914.4for the human probe) were purchased from Genedetect.com. These probes were hyperlabeled with Digoxigenin using the patented “GreenStar*” technology (GeneDetect). Hyperlabeled probes have 10 molecules of digoxigenin attached to the 3′ end of the probe. In situ hybridization with DIG-labeled oligonucleotide probes specific to MOR mRNA was carried out using a modified protocol as described below. The samples were kept in a humid chamber for the duration of the experiment. After rehydrating with 1X PB (100mL 25×PB concentrate (R&D Systems) in 2400mL DPEC-treated water (Fisher Scientific pH 7.2) 3×5 min, the samples were permeabilized using a proteinase K solution(1 μL PK (R&D Systems)/2mL PB)for 8 min at 37C. The digestion reaction was stopped using 0.01M PBS with 2mg/mL glycine (Sigma) for 5 min at RT. Following a 5 min wash with 0.01M PBS twice for 5 min, the samples were incubated with PHS (1mL Formamide/1mL Pre-hybridization Buffer; R&D Systems) for 5 min at RT. Fresh PHS was then added to the samples and they were kept at 55C in an Isotemp Incubator (Fisher Scientific) for 3h. Following the 3h incubation, hybridization solution (20 μL probe/980 μL PHS) was added. The samples were covered with Parafilm (Sigma) and promptly returned to the 55C incubator for 18–24 h (overnight). The next day the samples were washed for 5 min with PHS at 55C. The samples were then washed with the following solutions for 10 min on a Roto Mix rotary shaker (Thermolyne) at 55C: 75% PHS/ 25% SSC (2x; R&D Systems), 50% PHS/50% SSC (2x), 25% PHS/75% SSC (2x), 100%SSC (2x). Finally, the samples were washed twice in 100%SSC (0.2x; R&D Systems) for 15 min at 55C. Next, the samples were removed from the incubator and washed for 5 min with the following solutions at RT on the rotary shaker (25C): 75% SSC (0.2x)/PB, 50% SSC (0.2x)/PB, 25% SSC (0.2x)/PB, 100%PB, PB containing 2% heat- inactivated sheep serum (Jackson Immuno Research Laboratories).

In order to detect the DIG-labeled antisense Mu probes, an alkaline phosphatase-conjugated anti-DIG IgG (R&D Systems) was added to each sample. The detection antibody was prepared through two dilution steps. On the first day of the experiment, 4 μL of the stock anti-DIG IgG was added to 796 μL of PBS containing 2% heat-inactivated sheep serum and 10% w/v MLAP (Sigma) and stored overnight at 4C. On the following day, the 1:200 antibody was further diluted to 1:1000 in 3.2mL PB with 2% heat-inactivated sheep serum and the resulting solution was applied to the samples. The antibody-covered samples were incubated at 4C overnight. After washing (5×10 min) with PB, a 1x Tris/ Magnesium Chloride Solution (1mL) of Tris Buffer (R&D Systems)/ 1mL magnesium chloride solution (R&D Systems)/18mL RNAse free DPEC-treated water (Fisher), pH9.5) was applied to each sample (3×5 min). The labeled probes were visualized by applying a Detection Solution (1mL of the 1_x Tris/Magnesium Chloride Solution/3.5 μL BCIP/4.5 μL NBT (R&D Systems)) to each sample. Once satisfied with the signal strength, the reaction was stopped via the addition of 1x PB to each sample (3×1 min).

4.8. In situ hybridization controls

Control experiments were carried in order to firmly establish the level and specificity of the MOR mRNA signal. Fig. 3c′, shows no mRNA specific signal in the mouse cochlea incubated with oligonucleotide sense strands. Fig. 5d shows antisense oligonucleotide strands hybridized in the mouse spiral cord, neurons show specific mRNA signal in the cytoplasm.

4.9. Microscopic observation and documentation

The immunostained tissue sections were viewed and imaged with an Olympus BX51 fluorescent microscope (Olympus America Inc, NY, USA) equipped with an Olympus DP70 digital camera. To provide unbiased comparisons of the immunoreactive signal between each specimen, all images are captured using strictly the same camera settings. Images were acquired using Micro Suite TM Five software (Olympus America Inc). Images were processed using the Adobe Photoshop™ software program run on a Dell Precision 380 computer.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the generosity for donation of anti-MOR antibody from Dr Christopher J. Evans from the Hatos Center for Neuropharmacology, Department of Psychiatry and Biobehavioral Science, David Geffen School of Medicine, University of California at Los Angeles. Supported by The National Institute of Health grants DC05187-0, DA05010 and U24 DC011962 and 5U24DC008635 (NIDCD).

Abbreviations

- ORL-1

opioid receptor-like

- MOR

μ opioid receptor

- MOR-IR

Mu receptor immunoreactivity

- DAB

diaminobenzidine

- HRP

horse radish peroxidase

- PHS

pre-hybridization solution

- RT

room temperature

- MLAP

mouse liver acetone powder

References

- Ahmed S, Vorasubin N, Lopez IA, Hosokawa S, Ishiyama G, Ishiyama A. The expression of glutamate aspartate transporter (GLAST) within the human cochlea and its distribution in various patient populations. Brain Res. 2013;1529:134–142. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2013.06.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antonopoulos S, Balatsouras DG, Kanakaki S, Dona A, Spiliopoulou C, Giannoulis G. Bilateral sudden sensorineural hearing loss caused by alcohol abuse and heroin sniffing. Auris Nasus Larynx. 2012;39:305–309. doi: 10.1016/j.anl.2011.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arvidsson U, Riedl M, Chakrabarti S, Lee JH, Nakano AH, Dado RJ, Loh HH, Law PY, Wessendorf MW, Elde R. Distribution and targeting of a mu-opioid receptor (MOR1) in brain and spinal cord. J Neurosci. 1995;15:3328–3341. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.15-05-03328.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balaker AE, Ishiyama P, Lopez IA, Ishiyama G, Ishiyama A. Immunocytochemical localization of the translocase of the outer mitochondrial membrane (Tom20) in the human cochlea. Anat Record (Hoboken) 2013;296:326–332. doi: 10.1002/ar.22622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Besse D, Lombard MC, Zajac JM, Roques BP, Besson JM. Pre-and post synaptic distribution of mu,delta and kappa opioid receptors in the superficial layers of the cervical dorsal horn of the rat spinal cord. Brain Res. 1990;521:15–22. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(90)91519-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bourgoin S, Benoliel JJ, Collin E, Mauborgne A, Pohl M, Hamon M, Cesselin F. Opioidergic control of the spinal release of neuropeptides. Possible significance for the analgesic effects of opioids. Fundam Clin Pharmacol. 1994;8:307–321. doi: 10.1111/j.1472-8206.1994.tb00809.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blakley BW, Schilling H. Deafness associated with acetaminophen and codeine abuse. J Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2008;37:507–509. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Branford R, Droney J, Ross JR. Opiod genetics: the key to personalized pain control? Clin Genet. 2012;82:301–310. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0004.2012.01923.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christenson BJ, Marjala AR. Two cases of sudden sensorineural hearing loss after methadone overdose. Ann Pharmacother. 2010;44:207–210. doi: 10.1345/aph.1M250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ciorba A, Bovo R, Prosser S, Martini A. Considerations on the physiopathological mechanism of inner ear damage induced by intravenous cocaine abuse: cues from a case report. Aurix Nasus Larynx. 2009;36:213–217. doi: 10.1016/j.anl.2008.04.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Contet C, Kieffer BL, Befort K. Mu opioid receptor: a gateway to drug addiction. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2004;14:370–378. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2004.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eybalin M, Pujol R, Bockaert J. Opioid receptors inhibit the adenylate cyclase in the guinea pig cochleas. Brain Res. 1987;421:336–342. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(87)91303-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fex J, Altschuler RA. Enkephalin-like immunoreactivity of olivocochlear nerve fibers in cochlea of guinea pig and cat. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1981;78:1255–1259. doi: 10.1073/pnas.78.2.1255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fowler CG, King JL. Sudden bilateral sensorineural hearing loss following speed-balling. J Am Acad Audiol. 2008;19:461–464. doi: 10.3766/jaaa.19.6.2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freeman SR, Bray ME, Amos CS, Gibson WP. The association of codeine, macrocytosis and bilateral sudden or rapidly progressive profound sensorineural deafness. Acta Otolaryngol. 2009;129:1061–1066. doi: 10.1080/00016480802579082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedman RA, House JW, Luxford WM, Gherini S, Mills D. Profound hearing loss associated with hydrocodone/ acetaminophen abuse. Am J Otol. 2000;21:188–190. doi: 10.1016/s0196-0709(00)80007-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harell M, Shea JJ, Emmett JR. Total deafness with chronic propoxyphene abuse. Laryngoscope. 1978;88:1518–1521. doi: 10.1002/lary.1978.88.9.1518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ho T, Vrabec JT, Burton AW. Hydrocodone use and sensorineural hearing loss. Pain Physician. 2007;10:467–472. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Honda CN, Arvidsson U. Immunohistochemical localization of delta and mu-opioid receptors in primate spinal cord. Neuroreport. 1995;6:1025–1028. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199505090-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iqbal N. Recoverable hearing loss with amphetamines and other drugs. J Psychoactive Drugs. 2004;36:285–288. doi: 10.1080/02791072.2004.10399740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishiyama A, Ishiyama G, Baloh RW, Evans CJ. Heroin-induced reversible profound deafness and vestibular dysfunction. Addiction. 2001;96:1363–1364. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jongkamonwiwat N, Phansuwan-Pujito P, Casalotti S, Forge A, Dodson H, Govitrapong P. The existence of opioid receptors in the cochlea of guinea pigs. Eur J Neurosci. 2006;23:2701–2711. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2006.04810.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jongkamonwiwat N, Phansuwan-Pujito P, Sarapoke P, Chetwawang B, Casalotti S, Forge A, Dodson H, Govitrapong P. The presence of opioid receptors in rat inner ear. Hearing Res. 2003;181:85–93. doi: 10.1016/s0378-5955(03)00175-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kho S, Lopez IA, Evans C, Ishiyama A, Ishiyama G. Immunolocalization of Orphanin/FQ in rat cochlea. Brain Res. 2006;113:146–152. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2006.06.121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez I, Ishiyama G, Ishiyama A. Sudden sensorineural hearing loss due to drug abuse. Sem Hear. 2012;33:251–260. [Google Scholar]

- Lopez I, Ishiyama G, Tang Y, Frank M, Baloh RW, Ishiyama A. Estimation of the number of nerve fibers in the human vestibular end organs using unbiased stereology and immunohistochemistry. J Neurosci Methods. 2005;145:37–46. doi: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2004.11.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lioudyno MI, Verbitsky M, Holt JC, Elgoyhen AB, Guth PS. Morphine inhibits an alpha-9-acetylcholine nicotinic receptor-mediated response by a mechanism which does not involve opioid receptors. Hear Res. 2000;149:167–177. doi: 10.1016/s0378-5955(00)00180-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lupin AJ, Harley CH. Letter: inner ear damage related to propoxyphene ingestion. Can Med Assoc J. 1976;114:596. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDonald J, Lambert DG. Opioid receptors. CEACCP. 2005;5:22–25. [Google Scholar]

- Nishi M, Houtani T, Noda Y, Mamiya T, Nabeshima T, Yamashita T, Noda T, Sugimoto T. Unrestrained nociceptive response and disregulation of hearing ability in mice lacking the nociception/orphanin FQ receptor. EMBOJ. 1997;16:1858–1864. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.8.1858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nitescu P, Sjoberg M, Appelgren L, Curelaru I. Complications of intrathecal opioids and bupivacaine in the treatment of “refractory” cancer pain. Clin J Pain. 1995;11:45–61. doi: 10.1097/00002508-199503000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oh AK, Ishiyama A, Baloh RW. Deafness associated with abuse of hydrocodone/acetaminophen. Neurology. 2000;54:2345. doi: 10.1212/wnl.54.12.2345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pan YX, Xu J, Bolan E, Abbadie C, Chang A, Zuckerman A, Rossi G, Pasternak G. Identification and characterization of three new alternatively spliced mu-opioid receptor isoforms. Mol Pharmacol. 1999;56:396–403. doi: 10.1124/mol.56.2.396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polpathapee S, Tuchinda P, Chiwapong S. Sensorineural hearing loss in a heroin addict. J Med Assoc Thai. 1984;67:57–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Popper P, Cristobal R, Wackym PA. Expression and distribution of mu opioid receptors in the inner ear of the rat. Neuroscience. 2004;129:225–233. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2004.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pradhan AA, Smith ML, Kieffer BL, Evans CJ. Ligand- directed signaling within the opiod receptor family. Brit J Pharmacol. 2012;167:960–969. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2012.02075.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramsay BC. Complete nerve deafness after abuse of co-proxamol., 1991. Lancet. 1991;338:446–447. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(91)91070-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rigby MH, Parnes LS. Profound hearing loss associated with oxycodone-acetaminophen abuse. J Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2008;37:161–162. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sahley TL, Kalish RB, Musiek FE, Hoffman DW. Effects of opiod drugs on auditory evoked potentials suggest a role of lateral olivocochlear dynorphins in auditory function. Hear Res. 1991;55:133–142. doi: 10.1016/0378-5955(91)90099-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schrock A, Jakob M, Wirz S, Bootz F. Sudden sensorineural hearing loss after heroin injection. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2008;265:603–6. doi: 10.1007/s00405-007-0495-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sesena E, Vega R, Soto E. Activation of mu opioid receptors inhibits calcium-currents in the vestibular afferent neurons of the rat through a cAMP dependent mechanism. Front Cell Neurosci. 2014;8:90. doi: 10.3389/fncel.2014.00090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stenner M, Sturmer K, Beutner D, Klussman JP. Sudden bilateral sensorineural hearing loss after intravenous cocaine injection: a case report and review of literature. Laryngoscope. 2009;119:2441–2443. doi: 10.1002/lary.20711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soto E, Vega R. Neuropharmacology of vestibular system disorders. Curr Neuropharmacol. 2010;8:26–40. doi: 10.2174/157015910790909511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trescot AM, Datta S, Lee M, Hansen H. Opioid pharmacology. Pain Physician. 2008;11:133–153. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trigo JM, Martin-Garcia E, Berrendero F, Robledo P, Maldonado R. The endogenous opioid system: a common substrate in drug addiction. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2010;108:183–194. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2009.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime. World Drug Report. 2011 ( http://www.unodc.org/documents/data-and-analysis/WDR2011/The_opium-heroin_market.pdf)

- Vega R, Soto E. Opioid receptors mediate a postsynaptic facilitation and a presynaptic inhibition at the afferent synapse of axolotl vestibular hair cells. Neuroscience. 2003;118:75–85. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(02)00971-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Gaalen FA, Compier EA, Fogteloo AJ. Sudden hearing loss after a methadone overdose. Eur Arch Otorhionlaryngol. 2009;266:773–774. doi: 10.1007/s00405-009-0935-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waldhoer M, Bartlett SE, Whistler JL. Opioid receptors. Annu Rev Biochem. 2004;73:953–990. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.73.011303.073940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zuo Z. The role of opioid receptor internalization and b-arrestins in the development of opioid tolerance. Anesth Analg. 2005;10:728–734. doi: 10.1213/01.ANE.0000160588.32007.AD. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]